O-Train

| O-Train | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Owner | City of Ottawa |

| Locale | Ottawa, Ontario |

| Transit type | Light rail |

| Number of lines | 1 (+3 under construction) |

| Number of stations | 17 (+24 under construction) |

| Daily ridership | 74,700 (Q4 2023) [1] |

| Annual ridership | 19,451,800 (2023) [1] |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | October 15, 2001 |

| Operator(s) | OC Transpo |

| Character | At-grade, underground |

| Technical | |

| System length | 20.5 km (12.7 mi) (+45 km (28 mi) under construction) |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Average speed | 60 km/h (37 mph) (Trillium Line) |

| Top speed | 80 km/h (50 mph) |

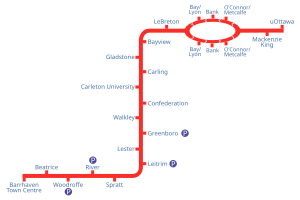

The O-Train is a light rail rapid transit system in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, operated by OC Transpo. The system consists of two lines: the electrically-operated Confederation Line (Line 1), running east to west, and the diesel-operated Trillium Line (Line 2), running north to south. Both lines are currently being extended as part of the Stage 2 project, with new segments being phased in between 2024 and 2027.

The O-Train network is fully grade separated and accessible, featuring low-floor trains that allow for easy boarding.[2] It includes a 2.5 km tunnel in the downtown core, while the remainder of the network operates on surface-level light rail tracks.

The next phase of expansion will see the southward extension of Line 2 to Limebank station, along with the addition of a new line (Line 4) that will connect Line 2 to Ottawa International Airport.[3] This expansion includes five newly constructed stations. Since May 2020, Stage 2 construction has temporarily shut down Line 2, with an expected reopening in late 2024.

Line 1 is being extended in both directions, with the eastward extension to Trim station in Orleans scheduled to open first in 2025. By 2027, the westward expansion of Line 1 to Algonquin station and the construction of Line 3 stations to Moodie station in the west end are expected to be completed. These expansions will bring the system's total length to 64.5 km (40.1 mi), with four lines and 41 stations.[4]

Name

[edit]The system's name was proposed by Acart Communications, an Ottawa advertising agency. The name "O-Train" was based on the classic Duke Ellington signature tune "Take the 'A' Train", which refers to the New York City Subway's A train. Because Ottawa is a bilingual city, the name had to work in both English and French. It survived an internal OC Transpo naming competition and was adopted soon after.

From its inception until 2014, the term "O-Train" initially referred to the north–south diesel line. With the construction of a second line, the east/west Confederation Line, the O-Train branding was extended to include both rail transit services, with the original service being renamed as the Trillium Line.[5]

Overview

[edit]

| Existing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line | Opened | Stations | Length | Technology |

| 2019 | 13 | 12.5 km (7.8 mi) | Electric light rail | |

| 2001 | 5 | 8 km (5.0 mi) | Diesel light rail | |

| Under construction | ||||

| 2025–2026 | 16 | 27.0 km (16.8 mi) | Electric light rail | |

| 2024 | 11 | 12 km (7.5 mi) | Diesel light rail | |

| 2024 | 3 | 4 km (2.5 mi) | Diesel light rail | |

The O-Train consists of two grade-separated lines:

- The Confederation Line is an electric light rail line running east–west from Blair to Tunney's Pasture. It connects to the Ottawa Transitway at each terminus and with the Trillium Line at Bayview. With the exception of the downtown tunnel portion, which includes three underground stations, the line runs using former Transitway bus rapid transit infrastructure.[6] St-Laurent is the only underground station outside the downtown tunnel.

- The Trillium Line was a mostly single-tracked, 8 km (5.0 mi) diesel light rail line that ran north to south from Bayview to Greenboro, where it connected to the Transitway. Trains passed each other via three passing loops, two of which are between stations and the third of which is located at Carleton station. The line has been closed since May 2020 for numerous upgrades as part of the Stage 2 project and is being served by a replacement bus service. It is expected to reopen in the third quarter of 2024.[7]

History

[edit]Pilot project

[edit]The Trillium Line (the original O-Train line) was introduced in 2001 as a pilot project to provide an alternative to the busways on which Ottawa had long depended exclusively for its high-grade transit service (see Ottawa Rapid Transit). The system uses low-floor diesel multiple unit trains. It is legally considered a mainline railway despite its use for local public transport purposes, and is more like an urban railway rather than a metro or tramway. It is often described as "light rail", partly because there were plans to extend it into Ottawa's downtown as a tramway-like service, and partly because the original Bombardier Talent trains are smaller and lighter than most mainline trains in North America and do not meet the Association of American Railroads' standards for crash strength.

Early extension plans

[edit]On July 12, 2006, Ottawa City Council voted by a vote of 14 to 7, with 1 councillor absent, to award the north–south expansion to the Siemens/PCL/Dufferin design team. The proposed extension, which was not undertaken, would have replaced the Trillium Line with an electric LRT system running on double track, as opposed to the current single-track diesel system.

According to the plan, the line was to be extended east from its current northern terminus to run through LeBreton Flats and downtown Ottawa as far as the University of Ottawa, and south-west from its Greenboro terminus to the growing Riverside South community and Barrhaven. Much of the route would have run through the undeveloped Riverside South area to allow a large new suburb to be constructed in the area south of the airport. The line would not have connected to the airport. Construction of the extension was scheduled to begin in the autumn of 2006, resulting in the shutdown of operations in May 2007, and to have been completed in autumn 2009 with operations resuming under the new systems and rolling stock.

The diesel-powered Talents would have been replaced with electric trams more suitable for on-street operation in the downtown area, specifically the Siemens S70 Avanto (due to the "design, build, and maintain" contracting process which has focused upon the bid proposing this vehicle).[8] Other bids had proposed the Bombardier Flexity Swift and a Kinki Sharyo tram.

With the use of electric power, greater frequency, and street-level running in central Ottawa, the expanded system would have borne much more resemblance to the urban tramways usually referred to by the phrase "light rail" than does the pilot project (though the use of the Capital Railway track and additional existing tracks which have been acquired along its route may cause it to remain a mainline railway for legal purposes).

The estimated cost of the north–south expansion would have been just under $780 million (not including the proposed maintenance facility), making the project the largest in the city's history since the Rideau Canal project. The federal and provincial governments had each promised $200 million for the expansion, with the city contributing the remainder of the cost using funds from various sources including the provincial gasoline tax, the city's transit reserve fund, and the Provincial Transportation Infrastructure Grant. 4.5% of the total project cost was expected to come from the property tax base. The city also requested studies on an extension of the railway from the proposed University of Ottawa terminus through to Hurdman Station.

Expansion controversies

[edit]The north–south expansion planning process became a source of great controversy. It was a major issue in the 2006 municipal election. The incumbent mayor Bob Chiarelli had long been the main advocate for light rail in Ottawa. Terry Kilrea, who finished second to Chiarelli in the 2003 municipal election and briefly ran for mayor in 2006, believed the plan was vastly too expensive and would also be a safety hazard for Ottawa drivers. He called for the entire light rail project to be scrapped. Mayoral candidate Alex Munter supported light rail but argued that the plan would do little to meet Ottawa's transit needs and that the true final expense of the project had been kept secret. He wanted to cut the Barrhaven leg and start work on an east–west line. Larry O'Brien, a businessman who entered the race late, wanted to postpone the project for six months before making a final decision.

Transport 2000 president David Jeanes, a longtime supporter of light rail in Ottawa and a member of the city's transportation advisory committee, stated that he believed that the project was being "designed to fail".[9] City transportation staff, though long in favour of bus rapid transit systems, disagreed with Jeanes's assessment.[10]

Numerous alternatives were proposed, including Alex Munter's plan,[11] the "Practical Plan" by the Friends of the O-Train,[12] and the Ottawa Transit group plan.

Cancellation of expansion

[edit]

On December 1, 2006, the new council took office. It started a debate on the issue during the week of December 4 with three options including the status quo, the truncation of portions of the current track or the cancellation of the contract. An Ottawa Sun article had reported on December 5 that if the project were cancelled, there could be lawsuits by Siemens against the city totalling as much as $1 billion.[13]

The new mayor, Larry O'Brien, opted to keep the extension to Barrhaven while eliminating the portion that would run from Lebreton Flats to the University of Ottawa. However, Council also introduced the possibility of building several tunnels in the downtown core in replacement of rail lines on Albert and Slater. Total costs for the tunnels would have been, according to city staff, about $500 million.[14] The council voted by a margin of 12–11 in favour of continuing the project, but without the downtown section. An environmental assessment was to be conducted on the possibility of building a tunnel through downtown. Another attempt made by Councillor Gord Hunter to review the project later failed.[15] At the same time, the Ontario government was also reviewing the project before securing its $200 million funding. However, it was reported that both the federal and provincial funding totalling $400 million was not secured before the contract deadline of December 15. O'Brien withdrew his support, and a new vote was held on December 14. With the presence of Rainer Bloess, who was absent during the previous vote,[16] the council decided to cancel the project by a margin of 13-11 despite the possibility of lawsuits from Siemens, the contract holder. It was reported on February 7, 2007, that the cost of the cancelled project was about $73 million.[17]

On February 14, 2007, it was reported that Siemens had written a letter to the city and gave two options. The first proposal was for the city to pay $175 million in compensation to Siemens in order to settle the dispute and cancel the contract. The second proposal was to re-launch the project with an additional price tag of $70 million to the cost of the original project.[18] Councillor Diane Deans had tabled a motion for a debate on February 23, 2007, but it was later cancelled. A poll conducted by the mayor's office showed that a majority of south-end residents disagreed with the cancellation of the project but only a third wanted to revive it.[19] In 2008, lawsuits against the city of Ottawa over its cancelled light rail system totalled $36.7 million.[20]

East–west line

[edit]The city also committed funds to perform an environmental assessment for an east–west route, running between Kanata and Orleans mainly via an existing railway right-of-way bypassing downtown. Planners initially explored the possibility of using the system's three Talents for an east–west pilot project after they were to be replaced by electric trams on the north–south line. Due to the cancellation of the north–south electrification project, any further plans for the diesel-powered trains on that route are uncertain. It was once thought that Transport Canada might not approve its use on the existing tracks for an east–west system, since they would have to be shared with other mainline trains. The city opted to do the westward expansion in stages, beginning with the east–west LRT Confederation Line.

Other possibilities

[edit]

Long-term plans had included lines on Carling Avenue from the existing Dow's Lake station westward to Bayshore and Bells Corners, and from the Rideau Centre south-east to the area of Innes Road and Blair Road via Rideau Street, Montreal Road, and Blair Road. The city has conducted a $4 million environmental assessment study for these two corridors. There were also possibilities of a rail link to Hurdman station.[citation needed]

Service to Gatineau would also be possible to serve commuters, as there is a railway bridge over the Ottawa River nearby, but the government of Gatineau was until 2016 opposed to extending the Trillium Line into its territory; Ottawa's city staff have taken steps to isolate the north–south line from the bridge,[21] so it would need to be re-built north of Bayview station. A line running into Gatineau was not included in the plans for expansion up to 2021.

Mayor's Committee on Transportation

[edit]In January 2007, Mayor Larry O'Brien formed a special committee to review the city's transportation needs and provide a report to city council by the beginning of June 2007. On June 1, this report[22] was presented to the mayor, and was subsequently released to the media and the public on June 6. This report was criticized by some for planning service to Smiths Falls and Arnprior while neglecting to plan service to Rockland and Embrun which were, at the time, rapidly growing communities east of Ottawa.

The committee, headed by the former member of parliament and cabinet minister David Collenette, recommended that Ottawa's needs would be best served by light rail through the future. This plan called for expansion of the system using rail rights-of-way and stations (Via Rail, CP Rail, and Ottawa Central Railway), constructing new stations and a tunnel through the downtown core, going through the former Union Station (now the Government of Canada Conference Centre). The plan called for using bi-mode diesel-electric trains or multiple units, allowing rapid expansion on current track powered by diesel engines, while switching to electric power through the tunnel downtown to remove the concerns about underground exhaust. Through the next thirty years, the plan called for expansion of up to six lines, including links to surrounding municipalities, the city of Gatineau and MacDonald-Cartier International Airport, with the lines gradually being electrified and expanded as required.

Only the initial portion of the project was budgeted, and using only rough numbers, but the committee felt that this could be completed for between $600 million to $900 million, including the downtown tunnel portion, within the following 5–10 years.

New transit plan

[edit]On November 28, 2007, the city council announced the expansion of rail service to Riverside South, as well as a downtown tunnel, with an environmental assessment study to determine whether it should be used by bus or rail service. Options were also open for additional extensions to Cumberland South to the east and south of Lincoln Fields Station at the Queensway via the transitway.[23]

On March 3, 2008, the city of Ottawa revealed four different options for its transit expansion plan, and presented at Open House consultation meetings during the same week. All plans included the construction of a downtown tunnel or subway to accommodate transit service and possible addition of businesses underground, as well as the expansion of rapid transit to the suburbs. One of the plans included light rail from Baseline Station to Blair Station and an expansion to the Ottawa Airport. All plans would have a completion date of about 2031, and costs were estimated at least $3 billion in total including $1 billion for the downtown tunnel.[24]

The majority of the public supported a downtown tunnel and the fourth transit option during public consultations meetings in Centretown, Barrhaven, Kanata and Orleans during the month. There were some suggesting that the light-rail service be extended to the suburbs rather than ending at the proposed stations. Concerns were particularly voiced by south-end residents where the initial rail plan was to be built.[25] On April 16, 2008, the Transit Committee tabled a document which recommended the fourth option.[26]

The plan was passed by the city council with a vote of 19–4 and included motions for possible rail extensions to the suburbs depending on population density and available funding.[27] However, Kitchissippi Ward councillor Christine Leadman expressed concerns of the environment integrity impacts of light-rail along the Kichi Zibi Mikan which is situated on NCC land. At least three councillors, including Leadman, Capital Ward councillor Clive Doucet and Kanata North Ward councillor Marianne Wilkinson, expressed preferences for light-rail service along Carling Avenue instead of the Parkway, although rail would run through many traffic lights and stops. The NCC also suggested that the city consider options other than the Kichi Zibi Mikan.[28] Three Ottawa Centre candidates for the 2008 federal election – incumbent New Democratic Party MP Paul Dewar, Liberal candidate Penny Collenette, and Conservative candidate Brian McGarry – also expressed opposition to building a light-rail line along the Parkway.[29]

Another potential route identified between Lincoln Fields and the Transitway near Westboro was a small strip of land located on the southern side of Richmond Road near the location of the defunct Byron Avenue streetcar line although costs would be much higher than the Parkway route.[30]

In early September 2008, city staff suggested that the first phase of the transit plan to be built would be similar to Option 3 with rail service from Riverside South to Blair Station via a downtown tunnel, the construction of a by-pass transit corridor via the General Hospital and a streetcar circuit along Carling Avenue, although Alex Cullen mentioned that Council already rejected the option of streetcars running on that road.[31]

Confederation Line

[edit]On December 19, 2012, the city council unanimously approved the construction of the Confederation Line, to run east–west from Blair to Tunney's Pasture.[6] The line runs on an existing Transitway infrastructure, with the exception of the 3-stop downtown tunnel. It began service in September 2019.

Stage 2

[edit]Stage 2 is the ongoing project to add 44 kilometres of light rail and 24 new stations in addition to stage 1 of the Confederation Line that was opened in September 2019. Initially approved in 2013, it will bring 77% of Ottawa residents within 5 km (3.1 mi) of rail. The expansion began construction in Q2 2019, and is expected to be entirely complete by 2026 with the extension south complete in 2024, east in 2025 and west in 2026.[32]

The project is made up of three extensions: an eastern extension of the Confederation Line by five stations from Blair station to Trim Road, a western extension by 11 stations from Tunney's Pasture to Baseline station and Moodie station with a split at Lincoln Fields station, and an upgrade of the Trillium Line that includes two new stations along the existing alignment, an extension southwards by four stations to a new Limebank station, and a branch line to the Macdonald-Cartier International Airport.[33]

On March 6, 2019, the Ottawa City Council voted 19–3 to approve the C$4.66 billion contracts to begin construction of the Stage 2 plan. The southern extension of the Trillium Line was awarded to TransitNext (solely operated by SNC-Lavalin), while the East and West extension of the Confederation Line was awarded to East West Connectors, a partnership between Vinci SA and Kiewit Corporation.[34] Financial close was reached with TransitNext on March 29, 2019, and a month later with East West Connectors.[35]

Construction

[edit]Construction began in 2019 with preliminary tree removal, utility work and road realignments. Work on the new rail yard for the Trillium Line as well as guideway work for the southward extension and airport link began over the summer of 2019.[36] On May 3, 2020, the Trillium Line closed to allow upgrades to the existing alignment to be completed.[37] On September 25, 2020, construction of the cut and cover tunnels for the westward Confederation Line extension began.[38]

Future extensions

[edit]Multiple major extensions of the O-Train are currently under construction or in the planning stages. This includes the above described Stage 2, as well as a future Stage 3 expansion plan.

| Project | Status | Description | Length | Expected opening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trillium Line South Extension[39] | Under construction | Extends Line 2 south from Greenboro station to South Keys, Bowesville, and Riverside South. Includes six new stations and improvements to five existing stations along the original 8 km (5.0 mi) route. | 12 km (7.5 mi) | 2024 |

| Airport Link[40] | Creates Line 4, branching off of Line 2 at the future South Keys station to Ottawa Macdonald–Cartier International Airport with an intermediate stop at Uplands station. | 4 km (2.5 mi) | 2024 | |

| Confederation Line East Extension[41] | Extends Line 1 east from Blair station to a new terminus at Trim Road in Orleans. The extension will run down the median of Highway 174 with five new stations. | 12 km (7.5 mi) | 2025 | |

| Confederation Line West Extension[42] | Extends Line 1 and creates Line 3 running west from Tunney's Pasture to Moodie Drive and Algonquin College. The extension will split at Lincoln Fields with Line 3 continuing West to Moodie Drive and Line 1 continuing south to Algonquin College. The extension will involve two cut-and-cover tunnels totaling 3 km (1.9 mi) in length and will add a total of 11 new stations. | 15 km (9.3 mi) | 2027 | |

| Kanata Extension[43] | Environmental Assessment Complete | Extends Line 3 west from Moodie Drive to Kanata, with eight new stations and a new terminus at Hazeldean Road. The project would be a part of O-Train Stage 3. | 11 km (6.8 mi) | After 2031[a] |

| Barrhaven Extension[44] | Extends Line 1 south to Barrhaven Town Centre from Algonquin College, with seven new stations and a new Light Rail Maintenance and Storage Facility in Barrhaven. | 10 km (6.2 mi) | After 2031[a] | |

| Carling LRT[45] | Proposed | A new at-grade LRT line running down Carling between Dow's Lake and Lincoln Fields. | 6.6 km (4.1 mi) | After 2031 |

STO connection

[edit]The O-Train could potentially become a connection point with the proposed Gatineau LRT system, to be run by the STO, which is planned to operate partly on the Ottawa side of the river.[46] On May 15, 2020, the city of Gatineau presented two options to integrate its proposed LRT with Ottawa's transit system: either running the new LRT on the surface along Wellington Street to Elgin Street, or constructing a new tunnel below Sparks Street to Elgin.[47] The surface option on Wellington also includes the possibility of creating a future transit loop by having the LRT cross back into Gatineau via the Alexandra Bridge. In May 2021, Gatineau announced that it found the Sparks Street tunnel option to be the "optimal solution," while noting the surface option remains a possibility should the tunnel prove to be unfeasible.[48]

Construction sinkholes

[edit]On February 21, 2014, an 8 metre wide, 12 meter deep sinkhole opened above the LRT tunnel excavation site at Waller Street south of Laurier Avenue, interrupting electricity, water, sanitation, and storm services in the area, and forcing the rerouting of traffic and a temporary halt of LRT tunnelling. Though the cause of the sinkhole was not confirmed, CBC News reported that the deputy city manager, Nancy Schepers, said that "monitoring equipment has confirmed that the impact is localized, and the geotechnical team has not identified any safety concerns at this point".[49]

On June 8, 2016, a section of Rideau Street collapsed in the vicinity of excavations being made for the Rideau station of the Confederation Line, prompting the road's closure to all traffic until July 2, 2016.[50] Later that year on October 2, a much smaller sinkhole opened in the same area.[51] Due to the sinkholes, Rideau Street was closed to regular traffic from Sussex to Dalhousie, excepting buses, taxis, construction vehicles, and delivery vehicles, until December 2020.[52]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "American Public Transportation Association Q4 2023 Ridership Report" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. March 4, 2024. Retrieved 2024-04-19.

- ^ Chan, Kenneth (November 29, 2018). "Ottawa's new $2.1-billion metro train system is opening in 2019". Daily Hive. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ "Line 2 closing for O‑Train expansion | OC Transpo". www.octranspo.com. Retrieved 2021-07-12.

- ^ "Future O-Train Network". OC Transpo. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ "O-Train name approved for Ottawa light rail system". CBC News Network. September 17, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Confederation Line". City of Ottawa. 2015. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ Joanne Chianello; Kate Porter (17 December 2021). "Trillium Line extension now delayed to spring 2023". CBC. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "Report Apr 07 EN", City of Ottawa

- ^ "Ottawa Light Rail Project Issues". Transport 2000. March 1, 2006.

- ^ "Transportation Committee Minutes 37". City of Ottawa. March 1, 2006.

- ^ Jake Rupert (October 25, 2006). "Chiarelli attacks Munter's light-rail alternative". Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ "Friends of the O-Train". Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ Puddicombe, Derek (December 5, 2006). "City fears $1B LRT lawsuit". Ottawa Sun.

- ^ Zakaluzny, Roman (December 5, 2006). "Council talks LRT one more time". Ottawa Business Journal. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ Elayoubi, Nelly (December 6, 2006). "Mayor's vote saves LRT project". Ottawa Sun.

- ^ "Absent councillor's vote could have stopped light rail approval". CBC News. December 8, 2006. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012.

- ^ Pringle, Josh (February 7, 2007). "Cancelled LRT Price Tag $73 Million". CFRA. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- "Ottawa's light rail project veers off-track". CBC News. December 13, 2006.

- "Ottawa council kills light rail project". CBC News. December 14, 2006. - ^ "Ottawa's light rail gets another chance". CBC News. February 14, 2007.

- ^ "Ottawa's light rail deal dead for good". CBC News. February 23, 2007.

- ^ "Ottawa LRT settlement reached for $36.7M". CBC Ottawa. September 11, 2009. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ "516". Ottawa Life. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ "Welcome to Moving Ottawa". Moving Ottawa.

- ^ Rupert, Jake (November 29, 2007). "Council sets $2-billion transit priorities : Councillors admit finding cash, deciding what to build first 'difficult'". The Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ Dare, Patrick (March 4, 2008). "$1B tunnel worth the cost, mayor says". The Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ "South-enders angered by Ottawa's new transit plan". CTV Ottawa. March 7, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Rupert, Jake (April 16, 2008). "Transit plan : City staff recommends a light-rail spine and downtown subway with bus transitways feeding it". The Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ Rupert, Jake (May 28, 2008). "Passed: City council approved a new mass transit system based on electric light rail Wednesday". The Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ Adam, Mohammed (September 10, 2008). "NCC wants 'other options' to parkway rail". The Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ Doolittle, Nadine (September 15, 2008). "City's voice lost in rail talk". Metro.

- ^ Rupert, Jake (June 30, 2008). "The three-kilometre controversy". Ottawa Citizen.

- Puddicombe, Derek (July 17, 2008). "Route gathers steam". Ottawa Sun. - ^ Puddicombe, Derek (September 12, 2008). "Trams and trains in transit tryouts". Ottawa Sun.

- ^ "Stage 2 - East, West and South". City of Ottawa. 2015. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- Blewett, Taylor. "LRT Stage 2 now $1.2B more than projected". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved February 24, 2019. - ^ Dept, Transportation Services (2020-09-29). "Stage 2 Light Rail Transit Project". Ottawa. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ "$4.7B LRT expansion gets green light". CBC. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ "City of Ottawa and TransitNext reach financial close on Stage 2 Trillium Line South extension". Stage2LRT.

- ^ "Stage 2 LRT Project Update : July 22, 2019 to August 4, 2019 - O-Train Fans". Railfans. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ "Line 2 closing for O‑Train expansion". www.octranspo.com. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

- ^ Dept, Innovative Client Services (September 25, 2020). "City digs into Stage 2 LRT construction". Ottawa. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ "Trillium Line South Extension". City of Ottawa. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Trillium Line South Extension Overview". City of Ottawa. 27 June 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ "Confederation Line East Extension". City of Ottawa. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Confederation Line West Extension". City of Ottawa. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Kanata Extension". CBC News. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "Barrhaven Extension". City of Ottawa. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Transportation Master Plan" (PDF). 2013-11-01. Retrieved 2021-06-09.

- ^ "STO confirms Gatineau will get light rail".

- ^ "Another transit tunnel? Planners weigh options for Outaouais-to-Ottawa commuters". ottawacitizen.com. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ "Update - Announcement of the optimal solution". www.sto.ca. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ "Road collapse leaves 8-metre wide sinkhole at tunnelling site". CBC. February 21, 2014.

- ^ "Infrastructure failure at Rideau and Sussex". City of Ottawa. 30 June 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ "City reopens section of Rideau Street after a small sinkhole opened up". Ottawa Citizen. October 3, 2016.

- ^ "Rideau Street ready for its big reveal". December 16, 2020.

External links

[edit]- "O-Train Line 1".

- "O-Train Line 2". formerly called the Trillium Line

- "Stage 2 LRT". Archived from the original on 2020-01-11.

- "Track layout". CartoMetro.

- "Stage 2". User Content on Google Maps.