2018 East Timorese parliamentary election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

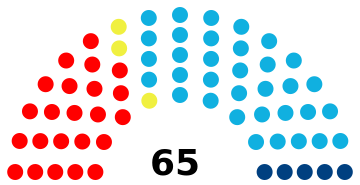

All 65 seats in the National Parliament 33 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 80.98% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This lists parties that won seats. See the complete results below.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

| Constitution |

|

|

Early parliamentary elections were held in East Timor on 12 May 2018 after the National Parliament was dissolved by President Francisco Guterres on 26 January 2018.[1]

The Alliance for Change and Progress (AMP), a coalition of three opposition parties, won an absolute majority of 34 of the 65 seats in Parliament.[2] Voter turnout was 81 percent, five percentage points higher than the previous year.[3] 784,286 people were eligible to vote.[4]

Background[edit]

In the 2017 parliamentary elections there was no clear winner, with the Fretilin party of Mari Alkatiri holding only one more seat than the National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction led by Xanana Gusmão. After the Kmanek Haburas Unidade Nasional Timor Oan (KHUNTO) backed out at short notice, Alkatiri formed a minority government with the Democratic Party,[5] which held only 30 of the 65 seats in the National Parliament. The opposition parties National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction (CNRT), People's Liberation Party (PLP) and KHUNTO then formed the Alliance for Change and Progress (AMP) in parliament.

After Alkatiri was unable to push through his budget or the government program against the AMP, the AMP asked President Francisco Guterres to give the coalition the mandate to form a new government.[6] Instead, after talks with representatives of all parties and amidst political deadlock, Guterres dissolved Parliament on 26 January 2018 (Presidential Decree No. 5/2018) and called early elections in accordance with the wishes of Fretilin and PD.[7][8] The bypassing of the parliamentary majority by President Guterres was judged by commentators and state scholars as an "attack on democracy". He and Alkatiri were accused of "stubbornness" and "arrogance". The prime minister would break the law just to be able to stay in power.[9]

The end of the border dispute between Australia and East Timor came in the period between the dissolution of parliament and the new election. Xanana Gusmão, the leader of the CNRT, as East Timor's chief negotiator, had been able to successfully conclude a new treaty on the border in the Timor Sea. On 6 March 2018, he was given a triumphant reception by thousands of East Timorese on his return to Dili.[10]

Electoral system[edit]

On 7 February 2018 President Guterres set the election date for 12 May.[11] On 3 April, the order of parties and alliances on the ballot paper was determined.[12] As in the previous elections in 2017, East Timorese living abroad were able to vote there. Polling stations were located in Lisbon, Porto, Darwin, Sydney, Melbourne, London, Oxford, Dungannon and Seoul.[13]

The 65 members of the National Parliament were elected from a single nationwide constituency by closed list proportional representation. Parties were required to have a woman in at least every third position in their list. Seats were allocated using the d'Hondt method with the last seat, in the case of several equal maximum numbers, being awarded to the party with the fewest votes.[14][15][16] With seats allocated at an electoral threshold of four percent.[17][18]

As in previous elections, once voters had voted, they were marked on their finger with a purple, non-washable ink to prevent double voting. The 4000 bottles of ink were purchased through the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) at a cost of $110,000. Transport costs were added to this.[19]

Parties and alliances[edit]

On 26 January the AMP and the Forum of National Democracy (FDN), an alliance (Portuguese: coligação) of several small parties that are not represented in parliament, concluded an agreement to unite the forces of the twelve parties in the upcoming elections. On 1 February 2018, the three parties of the AMP officially decided to work together in the election campaign as well. For this purpose, the alliance was renamed Alliance for Change and Progress.[20] In a declaration of intent, it was agreed to contest the election with a joint list and to form a coalition after the election. Other forces, such as the FDN, would also be free to join the AMP.[12] Fretilin and PD also agreed to cooperate in the election campaign. However, a joint list was ruled out by Alkatiri.[21] With the Frenti Dezenvolvimentu Demokratiku (FDD), the parties Democratic Unity Development Party (PUDD), Frenti-Mudança (FM), Timorese Democratic Union (UDT) and Party of National Development (PDN) founded another alliance on 11 December 2017.

In March 2018 the FDN disintegrated. Parts of it formed the Social Democratic Movement (MSD), others the National Development Movement (MDN). Finally, the Comissão Nacional de Eleições announced that it would allow a total of four coalitions to stand for election: AMP, MSD, MDN and FDD. If the parties received the same number of votes in the new elections as in 2017, the AMP would get 33 seats and thus an absolute majority of seats. Fretilin would get 21 seats, the PD six and the FDD, whose members were not previously represented in parliament, a total of five seats. The other alliances would be below the four-percent hurdle even with a combined vote total.[12]

In addition to the four party alliances, four parties contested the election: Fretilin and PD, the two governing parties previously represented in parliament, as well as Republican Party (PR) and Hope of the Fatherland Party (PEP). The list of candidates participating in the election had to be published on 1 January. The list of candidates participating in the election had to be confirmed by the East Timor Supreme Court of Justice on 1 April. Appeals against the decision could still be lodged until 4 April. An appeal will be lodged in April. At the end of March, it was reported that the Klibur Oan Timor Asuwain (KOTA), which did not run in 2017, and the Timorese Social Democratic Association (ASDT), which was not allowed to run at the time, had registered. However, the two parties no longer appeared on the lists published on 3 April.[22][23]

The parties remaining in the FDN, Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Party PDRT, Millennium Democratic Party PMD (both formerly in the Bloku Unidade Popular BUP alliance) and People's Party of Development PDP, made an election appeal in favour of the AMP.[24] The Timorese Democratic Party (PTD), which had run in 2017, also did not take part in the 2018 election. The registered parties People's Party of Timor (PPT), National Unity Party (PUN), East Timor National Republic Party (PARENTIL), Timorese Labor Party (PTT), Liberal Party (PDL), and Timorese Nationalist Party (PNT) did not take part in 2017.

Campaign[edit]

On 9 April, the parties and alliances signed a "Pact of National Unity", committing themselves to peaceful elections.[11] The hot phase of the election campaign officially began on 10 April and ended on 9 May. After that, no more election campaign events were allowed to take place.[12] The mood in the election campaign was generally very charged. The importance of social networks, such as Facebook, over traditional media continued to increase compared to previous elections, but this led to problems. Information was spread as well as insults, defamation and threats against politicians and traditional leaders. In the run-up to the official election campaign, the police arrested several people accused of insulting politicians. However, East Timorese criminal law does not provide for consequences for defamation, so those arrested were released. The tone on social networks did not change. There was also criticism that even journalists were spreading false news via social networks and thus causing resentment in society.[25]

On 5 May, two vehicles carrying 18 CNRT supporters were attacked in Viqueque, injuring several of the travellers. Marí Alkatiri apologized for the attack on behalf of Fretilin, but the NGO Fundasaun Mahein criticised the lack of measures to prevent such attacks. Moreover, the competition between the parties had been dominated by violent language, with party members commonly referred to as militants.[26] In Laga, according to AMP reports, there were also attacks on their supporters. On the other hand, there were some anti-Muslim statements, which was directed against Alkatiri, who is of Hadhrami origin.[27]

It was striking that the parties largely used figures from the independence struggle as figureheads for their campaigns. The AMP made special reference to the fact that its leaders Xanana Gusmão and Taur Matan Ruak came from the armed resistance in the country, while the Fretilin leaders Alkatiri and José Ramos-Horta spent the Indonesian occupation period (1975-1999) abroad on the "diplomatic front". The PD campaigned with its late founder Fernando de Araújo, who led the student independence movement in Indonesia (RENETIL), and the MSD with Mário Viegas Carrascalão and Francisco Xavier do Amaral, also deceased.[28][29][30]

On 10 May, the President of the National Electoral Commission (Portuguese: Comissão Nacional de Eleições CNE) Alcino Baris accused the AMP of spreading unfounded suspicions against the official electoral bodies on social media. Two posts on the AMP's Facebook account had warned that Prime Minister Alkatiri was "preparing mechanisms to deal with the early elections" with the CNE and the Technical Secretariat of the Electoral Administration (Portuguese: Secretáriado Técnico de Administração Eleitoral STAE). The party claims that additional ballot papers were printed "to make Fretilin the winner" and they tried to buy votes with "money and rice". Then also claim that election officials were also manipulated. According to Baris, there is no evidence of this. Fidelis Leite Magalhães, Vice-President of the AMP, said the warnings had certain bases and were intended to avoid abuse and "deliberate mistakes".[31][32] The first reports from national and international election observers assessed the elections as free, fair and transparent.[33] Besides Australia and the European Union, election observers included the International Republican Institute,[34] the Ibero-American Group of Electoral Observers GIOE with representatives from Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Portugal and Venezuela[35] and the Catholic Church alone 900 people.[36]

Results[edit]

Polling stations closed at 15:00.[37] Voter turnout was 81%, 5% higher than in the previous elections.[38][3] 326,272 of the votes cast were from men, 308,844 from women.[2] According to the provisional official final results after 98% of the votes were counted, the AMP won an absolute majority in parliament with 34 of 65 seats. It had to give up one seat to the new FDD, which won two more seats from the PD. Fretilinwas able to maintain its number of seats.[11] The AMP was able to win a majority in the municipalities, especially in the west. The Fretilin's second place behind the AMP in Oe-Cusse Ambeno was striking, for which the local Fretilin leader Arsénio Bano took personal responsibility and publicly apologised via Facebook, while doubts about the correctness of the result in Oe-Cusse Ambeno were heard from his party. Fretilin had lost almost 11% (more than 3,000 votes) here compared to the last elections, while AMP now had over 58% (+19%).[3][39] In Dili, Fretilin made big gains and became the strongest party again in its old strongholds of Baucau, Viqueque and Lautém.[40]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

| Alliance for Change and Progress (CNRT–PLP–KHUNTO) | 309,663 | 49.58 | 34 | –1 | |

| Fretilin | 213,324 | 34.16 | 23 | 0 | |

| Democratic Party | 50,370 | 8.07 | 5 | –2 | |

| Democratic Development Forum (PUDD–UDT–FM–PDN) | 34,301 | 5.49 | 3 | +3 | |

| Hope of the Fatherland Party | 5,060 | 0.81 | 0 | 0 | |

| National Development Movement (APMT–PLPA–MLPM–UNDERTIM) | 4,494 | 0.72 | 0 | 0 | |

| Republican Party | 4,125 | 0.66 | 0 | 0 | |

| Social Democratic Movement (CASDT–PSD–PST–PDC) | 3,188 | 0.51 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 624,525 | 100.00 | 65 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 624,525 | 98.33 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 10,591 | 1.67 | |||

| Total votes | 635,116 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 784,286 | 80.98 | |||

| Source: CNE | |||||

By municipality[edit]

| Municipality | AMP | FRETILIN | PD | FDD | PEP | MDN | PR | MSD | Valid votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local votes | |||||||||

| Aileu | 15,933 | 6,975 | 1,118 | 1,862 | 222 | 386 | 133 | 92 | 26,721 |

| Ainaro | 19,026 | 5,939 | 3,255 | 3,540 | 386 | 703 | 265 | 160 | 33,274 |

| Baucau | 27,027 | 35,612 | 2,532 | 2,031 | 406 | 216 | 432 | 393 | 68,649 |

| Bobonaro | 26,900 | 14,185 | 7,797 | 2,414 | 528 | 308 | 470 | 264 | 52,866 |

| Covalima | 17,536 | 8,896 | 6,332 | 1,890 | 271 | 202 | 252 | 104 | 35,483 |

| Dili | 71,763 | 45,206 | 5,881 | 4,847 | 600 | 546 | 405 | 496 | 129,744 |

| Ermera | 34,686 | 14,988 | 6,843 | 4,725 | 777 | 1,000 | 583 | 379 | 63,981 |

| Lautem | 12,344 | 15,394 | 5,057 | 946 | 187 | 86 | 207 | 146 | 34,367 |

| Liquica | 17,663 | 10,834 | 3,935 | 3,320 | 381 | 346 | 390 | 350 | 37,219 |

| Manatuto | 16,299 | 5,737 | 1,718 | 1,767 | 369 | 125 | 155 | 251 | 26,421 |

| Manufahi | 14,899 | 8,900 | 2,034 | 2,800 | 314 | 150 | 173 | 124 | 29,394 |

| Oecusse | 22,455 | 10,831 | 2,065 | 2,022 | 340 | 153 | 178 | 103 | 38,147 |

| Viqueque | 11,450 | 27,322 | 1,655 | 2,023 | 269 | 265 | 466 | 306 | 43,756 |

| Postal votes | |||||||||

| Australia | 314 | 441 | 25 | 36 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 7 | 844 |

| South Korea | 199 | 116 | 25 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 363 |

| Portugal | 140 | 289 | 38 | 33 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 515 |

| UK | 1,029 | 1,659 | 60 | 22 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2,781 |

| Total | 309,663 | 213,324 | 50,370 | 34,301 | 5,060 | 4,494 | 4,125 | 3,188 | 624,525 |

| Source: CNE Archived 2018-05-18 at archive.today | |||||||||

Aftermath[edit]

The PD leadership declared on 15 May that it would accept the election result and would pursue constructive opposition[41] Xanana Gusmão declared in a press conference on the same day that the AMP agreed to have the election results checked and countered suspicions of falsification from the ranks of Fretilin. Alkatiri expressed his suspicion that there were irregularities, particularly with regard to the result in Oe-Cusse Ambeno, which he wanted to have checked.[42] Gusmão also spoke of "small errors", saying that in Dili there were differences in the number of votes between the vote count and the published result of the STAE.[43] The CNE published the final, provisional result on 17 May.

On 19 May, Alkatiri announced that Fretilin was collecting evidence of "criminal electoral offences" to present to the Tribunal de Recurso, where the election results were being appealed. It said it already had several pieces of evidence from Oe-Cusse Ambeno where "cars with strangers" had been seen. However, they would accept any decision of the court.[44] The allegations included vote buying, use of false papers, missing ballot papers at a polling centre and complaints about the counting of votes.[45] On 22 May, the president of the tribunal, Deolindo dos Santos, requested further documents from the CNE. As these were missing for a judgement, the 72-hour deadline for a judgement had not yet expired.[46] On 23 May, the court rejected Fretilin's complaint as "completely unfounded".[45] and finally officially announced the final official result on 28 May, as scheduled in the electoral calendar in the Jornal da República.[46][47] Since then, Fretilin had announced its intention to be a strong opposition to the AMP government.[48]

On 1 June, the AMP nominated Taur Matan Ruak as its candidate for Prime Minister.[49][50] The new parliament met for the first time on 13 June. Taur Matan Ruak was sworn in as Prime Minister on 22 June.

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Nobel laureate blasts East Timor’s failure against poverty The Washington Post, 16 April 2018

- ^ a b c "Apuramento CNE 2018". CNE. 2018-05-27. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c Leach, Michael (2018-05-14). "In Timor-Leste, a vote for certainty • Inside Story". Inside Story. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "MEDIA STAE - Tetun | Português Evolusaun kona ba numeru eleitor resenseadu husi referendu 30 fulan agostu 1999 to'o Eleisaun Parlamentar iha 12 fulan Maiu 2018. Evolução do número de eleitores recenseados desde o referendo de 30 de Agosto de 1999 à Eleição Parlamentar de 12 de Maio de 2018. | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ Political deadlock augurs ill for Timor Leste Asia Times, 9 January 2018

- ^ Graça Feijó, Rui (2017-12-11). "Timor-Leste: is Díli on (Political) Fire Again? |". Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ President of East Timor: "Message of H.E The President of the Republic, 26 January 2018". Archived from the original on 2018-07-22. Retrieved 2023-01-04., retrieved on 4 January 2023

- ^ East Timor president dissolves Parliament to hold new elections Straits Times, 26 January 2018

- ^ Belo, Jose (26 January 2018). "Democracy under attack in Timor-Leste - UCA News". ucanews.com. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ Raimundos, Oki (2018-03-11). "Hero's welcome for Timor border negotiator". Western Advocate. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ a b c "2018 Early Parliamentary Election". www.laohamutuk.org. 12 April 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ a b c d SAPO: "Quatro coligações vão concorrer às eleições antecipadas de 12 de maio, 13 March 2018". Archived from the original on 2018-03-15. Retrieved 2023-01-04., Retrieved on 4 January 2023

- ^ La’o Hamutuk: List of polling stations, Retrieved on 4 January 2023

- ^ "IFES Election Guide | Elections: Timor-Leste Parl 2012". www.electionguide.org. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ "Electoral Act 06/2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2023-01-04. (PDF; 812 kB) and "Changes in 06/2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2023-01-04. (Portuguese; PDF; 173 kB), retrieved on 2023

- ^ Leach, Michael (24 July 2017). "Timor-Leste elections suggest reframed cross-party government". www.lowyinstitute.org. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ Electoral system Inter-Parliamentary Union

- ^ Fourth amendment to the Law on Election of the National Parliament Archived 2018-06-19 at the Wayback Machine CNE

- ^ Portugal, Rádio e Televisão de. "Timor compra através do PNUD tinta indelével para eleições antecipadas". Timor compra através do PNUD tinta indelével para eleições antecipadas (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ "AMP Avansa Pakote Uniku Hasoru Eleisaun Antesipada". The Timor News. 2018-02-01. Archived from the original on 2018-02-02. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ Lusa, Agência (6 February 2018). "Fretilin e PD, no Governo em Timor-Leste, podem fazer acordo pré-eleitoral". Observador (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "Timor-Leste/Eleições: Seis partidos e quatro coligações no voto antecipado de 12 de maio". Diário de Notícias (in European Portuguese). 22 March 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ STAE posting on Facebook: Lista definitiva de candidatos à eleição parlamentar 2018, 3 April 2018, Retrieved on 3 April 2018.

- ^ Picture from an election rally in Same, 18 April 2018., retrieved on 18 April 2018.

- ^ Lusa, Agência (22 March 2018). "Polícia timorense detém várias pessoas por insultos no Facebook a líderes nacionais". Observador (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ "Fundasaun Mahein Condemns use of violence preceding May 12 Election". Fundasaun Mahein. 8 May 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ Leach, Michael (2018-05-11). "Heated campaign draws to a close in Timor-Leste • Inside Story". Inside Story. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ Timor-Leste, J. T. Matebian, em (2018-04-09). "Coligações e partidos timorenses preparam-se para disputar eleições". Jornal Tornado (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ STAE: Internationale Wahlbeobachter.[dead link]

- ^ "MEDIA STAE - Observador nasional ba eleisaun parlamentar husi 12 maiu 2018 [Total: 2 993] Observadores nacionais à eleição parlamentar de 12 de maio de 2018 [Total: 2 993] | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ Leach, Michael (2018-05-11). "Heated campaign draws to a close in Timor-Leste • Inside Story". Inside Story. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ SIC Notícias: Órgãos eleitorais de Timor-Leste acusam oposição de publicações falsas em época de eleições , 10 May 2018, Retrieved on 9 January 2023.

- ^ Sainsbury, Michael (2018-05-13). "Xanana Gusmao alliance ousts Fretilin in Timor poll". The Age. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ "IRI Statement on Timor-Leste's Parliamentary Elections". International Republican Institute. 14 May 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ Press release from the Mexican consulate in East Timor.

- ^ Sainsbury, Michael (11 May 2018). "Church at center of controversy in Timor-Leste election - UCA News". ucanews.com. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ Raimundos, Oki (2018-05-15). "East Timorese vote in second election in less than a year". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "MEDIA STAE - Quadro comparativo do número de eleitores, participação / abstenção na eleição parlamentar 2017 e eleição parlamentar antecipada 2018. | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "Media STAE: Resultados provisórios Municípios / RAEOA e Diáspora - 884 actas apuradas. (Não inclui a acta do Suco Opa, Município Bobonaro)". www.facebook.com. 15 May 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ CNE: Votos ba partido iha munisipio keta-ketak, retrieved on May 17, 2018. (Dead)

- ^ "Lakon kadeira 2 iha EA, PD deside ba opozisaun iha PN – GMN TV | Grupo Média Nacional - Lori Timor ba Mundu". Grupo Média Nacional TV. 2018-07-03. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Independente: FRETLIN Taka Odamatan Ba Aliadu[permanent dead link] , May 15, 2018 , retrieved May 16, 2018. (Dead)

- ^ "Xanana Gusmão agradece maturidade do povo". SAPO Notícias. 2018-05-17. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ Lusa, Agência (19 May 2018). "Fretilin recolheu provas de "crimes eleitorais", afirma Mari Alkatiri". Rádio e Televisão de (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ a b Lusa, Agência (23 May 2018). "Tribunal de Recurso considera improcedente recurso da Fretilin". Rádio e Televisão de (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ a b Lusa, Agência (22 May 2018). "Timor-Leste/Eleições: Tribunal de Recurso pede mais dados à CNE para avaliar recurso - presidente". Diário de Notícias (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ "TR Proklama Rezultadu EAP-AMP Primeiru Vensedor". TATOLI Agência Noticiosa de Timor-Leste. 2018-05-28. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ "FRETILIN Sei Sai Opozisaun Forte Hodi Kontrola Governu AMP". The Timor News. 2018-05-28. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ Carvalho, Xénia de (2018-06-01). "Timor-Leste: Taur Matan Ruak nomeado primeiro-ministro timorense". e-Global (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ "Taur Matan Ruak indigitado pela coligação AMP como novo PM timorense -- fontes partidárias". Timor Agora. 19 June 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

Further reading[edit]

- Leach, Michael (10 April 2018). "Choices sharpen in Timor-Leste". Inside Story. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ——————— (11 May 2018). "Heated campaign draws to a close in Timor-Leste". Inside Story. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ——————— (14 May 2018). "In Timor-Leste, a vote for certainty". Inside Story. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to 2018 East Timorese parliamentary election at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 2018 East Timorese parliamentary election at Wikimedia Commons