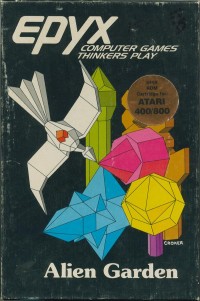

Alien Garden

| Alien Garden | |

|---|---|

| |

| Publisher(s) | Epyx |

| Designer(s) | Bernie De Koven[1] |

| Programmer(s) | Jaron Lanier Robert Leyland |

| Platform(s) | Atari 8-bit |

| Release | 1982 |

| Genre(s) | Non-game |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Alien Garden is a non-game for Atari 8-bit computers published by Epyx in 1982[2] by Bernie De Koven and programmed by virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier. Designed with an emphasis on the need for experimentation, Alien Garden was described by its creators as an art game,[3] and ranks among the earliest art games.[4] Its release predates Lanier's Moondust by a year.[5]

Gameplay

[edit]Gameplay consists of a side-scrolling world covered in 24 different kinds of crystalline flowers resembling gypsum flowers. The player controls an embryonic animal as it grows, survives and reproduces through 20 generations. Difficulty is introduced through the lack of instructions in the game. As such, the player must employ trial and error techniques to determine which flowers are edible, which flowers shrink or grow when stung, and which flowers are fatal or explosive when touched.[6] The player may use either the organism's tail, stinger, or wings to bump or otherwise make contact with them. To maintain the challenge, the behavior of the flowers changes every time the game is played. To increase the challenge, the score is repeated all along the left and right sides of the scrolling screen. As the score increases, the animal avatar is forced to travel more and more closely to the sometimes deadly crystal flowers.

Development

[edit]Alien Garden was designed by Bernie De Koven and programmed by Jaron Lanier and Robert Leyland for the Epyx brand of publisher Automated Simulations. This was one of De Koven's first works alongside Ricochet. He described designing these games as "like writing poetry" and recalled was "very free as there were so few established precedents" despite a 4 KB memory restriction.[7] He said that Alien Garden allowed him to challenge his own preconceptions of what a game should be. He used it as an example of his newfound freedom of expression in design, calling it "kind of like a trip, like some kind of psychedelic experience just to sit there with my eyes closed and imagine all these interactions taking place on the screen."[8]

De Koven desired for Alien Garden to be an alternative to the perilous, alien environments found in other many games of its time. "I wanted to make an alien world, but not one that was necessarily hostile," he said. "A world that had some danger, but also some beauty."[9] He later characterized Alien Garden as "a kind of art game, one that was beautiful to look at but required exploration to understand how to interact with the 'flowers' in the garden."[7] De Koven and Lanier worked together to define the graphical elements due to the memory limitations. The score on the play field's boundary was designed to take up more of the screen as the game progressed, increasing the challenge for the player.[8]

De Koven worked for Epyx for a little more than a year and a half prior to joining the Children's Computer Workshop.[7][9] Lanier was with Epyx for about one year before departing and developing his more well-known art game Moondust for Creative Software.[10][11] Leyland left Epyx to program Murder on the Zinderneuf for Free Fall Associates before a brief hiatus from the gaming industry.[12]

Reception

[edit]Electronic Fun with Computers & Games praised the game for its "graphically stunning" visuals as well as the experimentation and strategy required.[13] Computer Gaming World, however, harshly criticized the graphics, and felt that the lack of color was "particularly disappointing".[14]

References

[edit]- ^ here’s Bernie — DeepFUN

- ^ "Epyx". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ Thomsen, Michael (8 February 2010). "The Art Of Gaming". Edge. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012.

- ^ Pratt, Charles J. (8 February 2010). "The Art History... Of Games? Games As Art May Be A Lost Cause". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019.

- ^ Pease, Emma (14 May 1997). "Post Symbolic Systems". CSLI Calendar of Public Events. 12 (28). Stanford Center for the Study of Language and Information. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ Alien Garden Owners Manual. AtariAge entry. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ a b c American Journal of Play staff (Winter 2015). "Deep Fun and the Theater of Games: An Interview with Bernie DeKoven". American Journal of Play. Vol. 7, no. 2. The Strong. p. 150. ISSN 1938-0399. OCLC 226081597.

- ^ a b Juul, Jesper (August 22, 2017). "Interview with Bernie DeKoven". Jesper Juul. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Wiswell, Phil (June 1983). "Phil Wiswell's Gamemakers: The learning game". Electronic Fun with Computers & Games. Vol. 1, no. 8. Fun & Games Publishing. pp. 78–9. ISSN 0746-0546. OCLC 10488752.

- ^ Wiswell, Phil (December 1983). "Phil Wiswell's Gamemakers: Moon Duster". Electronic Fun with Computers & Games. Vol. 2, no. 2. Fun & Games Publishing. pp. 84–5. ISSN 0746-0546. OCLC 10488752.

- ^ Lanier, Jaron (November 21, 2017). Dawn of a New Everything: Encounters with Reality and Virtual Reality (1st ed.). Henry Holt and Company. p. 99. ISBN 978-1627794091.

- ^ Hickey Jr., Patrick (October 6, 2022). The Minds Behind PlayStation 2 Games: Interviews with Creators and Developers. McFarland & Company. p. 102. ISBN 978-1476685076.

- ^ Wiswell, Phil (May 1983). "Alien Garden". Electronic Fun with Computers & Games. Vol. 1, no. 7. p. 66.

- ^ Doum, Allen (March–April 1983). "The Atari Arena". Computer Gaming World. Vol. 3, no. 2. pp. 20, 22.

External links

[edit]- Alien Garden at Atari Mania

- Alien Garden can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- Manual at the Internet Archive