Emigration from the United States

Emigration from the United States is the process where citizens and nationals from the United States move to live in countries other than the US, creating an American Diaspora (Overseas Americans). The process is the reverse of the immigration to the United States. The United States does not keep track of emigration and counts of Americans abroad are thus only available based on statistics kept by the destination countries.

History

[edit]Due to the flow of people back and forth between the United Kingdom and its colonies, as well as between the colonies, there has been an American diaspora of a sort since before the United States was founded. During and immediately after the American Revolutionary War, a number of American Loyalists relocated to other countries, chiefly Canada and the United Kingdom.[1] Residence in countries outside the British Empire was unusual, and usually limited to the wealthy, such as Benjamin Franklin, who was able to self-finance his trip to Paris as a U.S. diplomat.

18th century

[edit]After the American Revolutionary War, some 3,000 Black Loyalists - slaves who escaped their Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the Crown's guarantee of freedom - were evacuated from New York to Nova Scotia; they were individually listed in the Book of Negroes as the British gave them certificates of freedom and arranged for their transportation.[2] The Crown gave them land grants and supplies to help them resettle in Nova Scotia. Other Black Loyalists were evacuated to London or the Caribbean colonies.[3]

Thousands of slaves escaped from plantations and fled to British lines, especially after British occupation of Charleston, South Carolina. When the British evacuated, they took many former slaves with them. Many ended up among London's Black Poor, with 400 resettled by the Sierra Leone Company to Freetown in Africa in 1787. Five years later, another 1,192 Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia chose to emigrate to Sierra Leone, becoming known as the Nova Scotian settlers in the new British colony of Sierra Leone. Both waves of settlers became part of the Sierra Leone Creole people and the founders of the nation of Sierra Leone.[3]

19th century

[edit]Thanks to the increase of whalers and clipper ships, Americans began to travel all over the world for business reasons.

The early 19th century also saw the beginning of overseas religious missionary activity, such as with Adoniram Judson in Burma.

During the War of 1812, some African American slaves joined the Corps of Colonial Marines to fight against the United States. Their reward was guaranteed emancipation (as per the Mutiny Act 1807) and new land set aside for them in southern Trinidad. They and their descendants later became known as the Merikins.

The middle of the 19th century saw the immigration of many New Englanders to Hawaii, as missionaries for the Congregational Church, and as traders and whalers. The American population eventually overthrew the government of Hawaii, leading to its annexation by the United States.

During this time the American Colonization Society established a colony in the Pepper Coast for freedmen known as Liberia. The ACS's main goals were to Christianize indigenous Africans, end the illegal slave trade, and resettle African Americans out of the United States. Their descendants became the Americo-Liberians, who dominated the country for most of its history.

During the early 19th century, particularly between 1824 and 1826, thousands of free blacks emigrated from the United States to Haiti to escape antebellum segregation and racist policy. They primarily settled in Samana Province, where their descendants still live today as the Samana Americans. They speak their own variety of English called Samana English.

During the American Civil War, President Lincoln asked Kansas Senator Samuel C. Pomeroy and Secretary of the Interior Caleb Blood Smith to develop a plan to resettle African Americans out of the United States. Pomeroy had come up with the idea of Linconia, a freedmen colony much like Liberia in modern Chiriqui Province, Panama. After nearby Central American nations expressed their opposition to the project, it was quickly scrapped. However, 453 African workers were sent to Ile-à-Vache in Haiti as part of a private colonization effort run by entrepreneur Bernard Kock. This colony was short-lived due to Kock breaking the contract. By the end of 1863, all of the colonists had returned to the United States.

After the Civil War, thousands of Southerners moved to Brazil, where slavery was still legal at the time. They founded a city called Americana and became known as Confederados.[4] Some also migrated to Mexico, where they established the New Virginia Colony with the help of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico. They founded their capital, Carlota, and had planned to make more settlements, but the colony was abandoned after the fall of the Second Mexican Empire, and most of the settlers returned to the U.S. There was also a sizeable presence of ex-confederates in British Honduras, now known as Belize.

In Asia, the U.S. government made efforts to secure special privileges for its citizens. This began with the Treaty of Wanghia in China in 1844. It was followed by the expedition of Commodore Perry to Japan 10 years later, and the United States–Korea Treaty of 1882. American traders began to settle in those countries.

Early 20th century

[edit]Many Americans migrated to the Philippines after it became a U.S. territory following the Philippine–American War.

Cecil Rhodes created the Rhodes Scholarship in 1902 to encourage greater cooperation between the United States, the British Empire and Germany by allowing students to study abroad.[5]

Interwar period

[edit]In the period between the First and Second World Wars, many Americans, particularly writers such as Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound, migrated to Europe to take part in the cultural scene.

European cities like Amsterdam, Berlin, Copenhagen, Paris, Prague, Rome, Stockholm, and Vienna came to host a large number of Americans. Many Americans, typically those who were idealistic and/or involved in left-leaning politics, also participated in the Spanish Civil War (mainly supporting the Republicans against the Nationalists) in Spain while they lived in Madrid and elsewhere.

Other Americans returned home to the countries of their origin, including the parents of American author/illustrator Eric Carle, who returned to Germany. Thousands of Japanese Americans were unable to return to the United States, after the Attack on Pearl Harbor.[6]

Éamon de Valera, the third Taoiseach of Ireland during the 1930s, was born in New York to an Irish mother and a Spanish father. He moved to Ireland at a young age with his mother's family.

Cold War

[edit]During the Cold War, Americans became a permanent fixture in many countries with large populations of American soldiers, such as West Germany and South Korea.

The Cold War also saw the development of government programs to encourage young Americans to go abroad. The Fulbright Program was established in 1946 to encourage cultural exchange, and the Peace Corps was created in 1961 both to encourage cultural exchange and a civic spirit of volunteerism.

With the formation of the state of Israel, over 100,000 Jews made aliyah to the holy land, where they played a role in the creation of the state. Other Americans traveled to countries like Lebanon, again to take place in the cultural scene.

During the Vietnam War, about 100,000 American men went abroad to avoid conscription, 90% of them going to Canada.[7] European nations, including neutral states like Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, offered asylum to thousands of American expatriates who refused to fight.

A small number of Americans abandoned the country for political reasons, defecting to the Soviet Union, Cuba, or other countries, such as Miguel d'Escoto Brockmann, and sixties radicals such as Joanne Chesimard, Pete O'Neal, Eldridge Cleaver, and Stokely Carmichael.

During this period Americans continued to travel abroad for religious reasons, such as Richard James, inventor of the Slinky, who went to Bolivia with the Wycliffe Bible Translators, and the Peoples Temple establishment of Jonestown in Guyana.

After the Cold War

[edit]The opening of Eastern Europe, Central Europe, and Central Asia after the Cold War provided new opportunities for American businesspeople. Additionally, with the global dominance of the United States in the world economy, the ESL industry continued to grow, especially in new and emerging markets. Many Americans also take a year abroad during college, and some return to the country after graduation.

21st century

[edit]Iraq War deserters sought refuge mostly in Canada and Europe, and NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden escaped to Russia.[8][9]

Increasing numbers of Americans retire abroad due to financial setbacks resulting from the 2008 financial crisis.[10]

Young Americans facing a tough job market due to the recession are also increasingly open to working abroad.[11]

According to a Gallup poll from January 2019, 16% of Americans, including 40% of women under the age of 30, would like to leave the United States.[12] In 2018, the Federal Voting Assistance Program estimated a total number of 4.8 million American civilians lived abroad, 3.9 million civilians, plus 1.2 million service members and other government-affiliated Americans.[13]

A survey by Arton Capital found that 53 percent of American millionaires are more likely to leave the country after the 2024 presidential election, regardless of who wins.[14]

Reasons for emigrating

[edit]There are many reasons why Americans emigrate from the United States. Economic reasons include job or business opportunities, or a higher standard of living in another country. Others emigrate due to marriage or partnership to a foreigner, for religious or humanitarian purposes, or to seek adventure or experience a different culture.[15] Many decide to retire abroad seeking a lower cost of living, especially more affordable health care.[16][17] Immigrants to the United States may decide to rejoin family members in their countries of origin. Other reasons include political dissatisfaction, safety concerns and cultural issues such as racism.[18] Some Americans may also emigrate to evade legal liabilities; a common past case was evasion of mandatory military service.

In addition to Americans who choose to emigrate as adults, many children are born in the United States to foreign temporary workers or international students and naturally move with their parents when they return to their countries of origin. Due to their acquisition of U.S. citizenship by birth but no significant connection to the country, they are sometimes called "accidental Americans".[19]

Destinations with facilitated access

[edit]One reason the U.S. diaspora is unusually small relative to its home population is that it is generally much more difficult for Americans to emigrate to a foreign country than, for example, citizens of countries in the Schengen Zone; similar to most other large countries, Americans looking for economic opportunity are generally limited to transmigration within the U.S.

In addition to U.S. territories, U.S. citizens have the right to reside in the Marshall Islands, Micronesia and Palau due to a Compact of Free Association between the United States and each of these countries. They may also freely move to Svalbard due to its open migration policy, as long as they are able to obtain housing and means of support there.[20][21] All of these jurisdictions, however, are tiny, with fewer than a half million people combined.

Americans with parents or ancestors from certain countries, such as Germany, Ireland and Italy, may be able to claim nationality via jus sanguinis and therefore move there freely. Germany and Austria also have an easier path to citizenship for descendants of victims of Nazi crimes, even if jus sanguinis does not apply in the specific case.[22][23] Similarly, American Jews may move to Israel under its Law of Return.

The USMCA (and previously NAFTA) allows U.S. citizens to work in Canada and Mexico in business or in certain professions, with few restrictions.[24] However, to obtain permanent residence they must still satisfy the regular immigration requirements in these countries.

Net effect

[edit]The United States is a net immigration country, meaning more people arrive in the U.S. than leave it. There is a scarcity of official records in this domain.[25] Given the high dynamics of the emigration-prone groups, emigration from the United States remains indiscernible from temporary country leave. There are a few countries in the Caribbean which had very high migration rates to the United States in the 1980s and 1990s but recorded higher population totals in recent years, indicating significant return migration from the U.S., such as Trinidad and Tobago between its 2000 and 2011 censuses.

Citizenship

[edit]Anyone born in the United States, with the sole exception of those born to foreign diplomats, acquires U.S. citizenship at birth. Those born abroad to at least one American parent also acquire U.S. citizenship if the parent had lived in the United States for a certain number of years. Immigrants to the United States may also become U.S. citizens by naturalization.

In the past it was possible for Americans abroad to lose U.S. citizenship involuntarily, but after Supreme Court decisions such as Afroyim v. Rusk and Vance v. Terrazas, along with corresponding changes in U.S. law, they can only lose U.S. citizenship in a very limited number of ways, most commonly by expressly renouncing it at a U.S. embassy or consulate.

Historically, few Americans renounced U.S. citizenship per year, but the numbers drastically increased after 2010 when the U.S. government enacted the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, requiring foreign banks to report information on American holders of bank accounts located outside the United States. More than 3,000 Americans renounced U.S. citizenship in 2013, many citing the financial disclosure requirements and difficulty in finding banks willing to accept them as customers.[26] More than 5,000 renounced in 2016, and more than 6,000 did in 2020.[27]

Issues

[edit]One of the biggest issues with the American diaspora is double taxation. Unlike almost all countries in the world, the United States taxes its citizens even if they do not live in the country. The foreign earned income exclusion mitigates double taxation on some income from work, but the Internal Revenue Code treats ordinary foreign savings plans held by residents of foreign countries as if they were offshore tax avoidance instruments and requires extensive asset reporting, resulting in significant costs for Americans at all income levels to comply with filing requirements even when they owe no tax.[28][29][30] Even Canada's Registered Disability Savings Plan falls under such reporting requirements.[31] The most prominent piece of legislation which has attracted the ire of Americans abroad is the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA). Disadvantages stemming from FATCA, such as hindering career advancement overseas, may decrease the number of Americans in the diaspora in future years. The problem is so severe that some Americans have addressed it by renouncing or relinquishing their U.S. citizenship.[32] Since 2013, the number of people giving up US citizenship has risen to a new record each year, with an unprecedented 5,411 in 2016, up 26% from the 4,279 renunciations in 2015.[33][34][35]

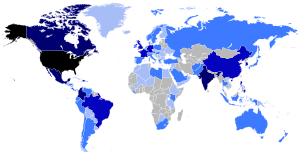

Statistics

[edit]There are no exact figures on how many Americans live abroad. The United States Census Bureau does not count Americans abroad, and individual U.S. embassies offer only rough estimates.

In 1999, a Department of State estimate suggested that the number of Americans abroad may be between three million and six million.[28][36] In 2016, the agency estimated 9 million U.S. citizens were living abroad,[37] but these numbers are highly open to dispute as they often are unverified and can change rapidly.[38]

According to the Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP), the Department of State's estimates are inflated on purpose as their purpose is to prepare for emergencies.[39] FVAP makes its own detailed estimates of the number of U.S. citizens abroad, by region and by country, and of those who are of voting age, based on a variety of sources such as censuses of other countries and U.S. tax and social security records. In 2018, it estimated about 4.8 million U.S. citizens abroad, of whom about 2.9 million were of voting age.[40] FVAP's estimates also fluctuate significantly, for example it had estimated about 5.5 million in 2016.[41] Most recently in 2022 FVAP estimated that 4.4 million U.S. citizens lived abroad and 2.8 million of them were 18 and were eligible to vote in federal elections.[42]

The United Nations estimates the number of migrants by origin and destination of all countries and territories. In 2019, the organization estimated that about 3.2 million people from the United States were living elsewhere.[43] This number is mostly based on country of birth recorded in censuses, so it does not include U.S. citizens who were not born in the United States, such as those who acquired U.S. citizenship by descent or naturalization.

One indicator of the U.S. citizen population overseas is the number of Consular Reports of Birth Abroad requested by U.S. citizens from a U.S. embassy or consulate as a proof of U.S. citizenship of their children born abroad. The Bureau of Consular Affairs reported issuing 503,585 such documents over the decade 2000–2009. Based on this, and on some assumptions about the family composition and birth rates, some authors estimate the U.S. civilian population overseas as between 3.6 and 4.3 million.[44]

Sizes of certain subsets of U.S. citizens living abroad can be estimated based on statistics published by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). U.S. citizens with income above a certain level are required to file a U.S. income tax regardless of where they reside. During 2019, the IRS recorded about 739,000 U.S. tax returns filed with a foreign address, representing about 1.3 million people including spouses and dependents.[45] Other indicators are the number of U.S. tax returns with a partial exclusion on income from work abroad (about 476,000 in 2016[46]) and those reporting foreign income other than passive income (about 1.5 million in 2016[47]), but not all of these were from people actually residing abroad full-time.

Estimates by country

[edit]

The list below is of the main countries hosting American populations. Those shown with exact counts are enumerations of Americans who have immigrated to those countries and are legally resident there, does not include those who were born there to one or two American parents, does not necessarily include those born in the U.S. to parents temporarily in the U.S. and moved with parents by right of citizenship rather than immigration, and does not necessarily include temporary expatriates.

Mexico – 899,311 United States-born residents of Mexico (2017)[48]

Mexico – 899,311 United States-born residents of Mexico (2017)[48] European Union – 800,000 (2013; all EU countries combined)

European Union – 800,000 (2013; all EU countries combined) Canada – 738,203 (2011)[49]

Canada – 738,203 (2011)[49] India – 700,000 according to a press release from the White House on 12/06/2017[50]

India – 700,000 according to a press release from the White House on 12/06/2017[50] Philippines – 600,000 (2015)[51]

Philippines – 600,000 (2015)[51] Germany – 400,000 (2020)[52]

Germany – 400,000 (2020)[52] Brazil – 260,000[53]

Brazil – 260,000[53] Israel – 185,000[54]

Israel – 185,000[54] United Kingdom – 158,000 (2013)[55]

United Kingdom – 158,000 (2013)[55] South Korea – 140,222 (2016)[56][57]

South Korea – 140,222 (2016)[56][57] Costa Rica – 130,000[58] to 170,000[59]

Costa Rica – 130,000[58] to 170,000[59] Australia – 109,450 (2021)[60]

Australia – 109,450 (2021)[60] France – 100,619 (2008)[61]

France – 100,619 (2008)[61] Japan – 88,000 (2011)[62]

Japan – 88,000 (2011)[62] Dominican Republic – 15,000[54]

Dominican Republic – 15,000[54] China – 71,493 (2010, mainland China only)[63][64]

China – 71,493 (2010, mainland China only)[63][64] Italy – 54,000[54]

Italy – 54,000[54] Spain – 48,225[65]

Spain – 48,225[65] Hong Kong – 60,000[64]

Hong Kong – 60,000[64] Pakistan – 52,486[66]

Pakistan – 52,486[66] Netherlands – 47,408 (2021)[67]

Netherlands – 47,408 (2021)[67] United Arab Emirates – 40,000[68]

United Arab Emirates – 40,000[68] Republic of China (Taiwan) – 38,000

Republic of China (Taiwan) – 38,000 Belgium – 36,000[68]

Belgium – 36,000[68] Saudi Arabia – 36,000[68]

Saudi Arabia – 36,000[68] Switzerland – 32,000[68]

Switzerland – 32,000[68] Poland – 31,000 to 60,000 [68]

Poland – 31,000 to 60,000 [68] Lebanon – 25,000[69]

Lebanon – 25,000[69] Panama – 25,000[70]

Panama – 25,000[70] Colombia –21,000 (2019)[71]

Colombia –21,000 (2019)[71] Kuwait – 20,000[54]

Kuwait – 20,000[54] Norway – 19,000[54]

Norway – 19,000[54] New Zealand – 17,748 (2006)[72]

New Zealand – 17,748 (2006)[72] Sweden – 16,555 (2009)[73]

Sweden – 16,555 (2009)[73] Austria – 15,000[68]

Austria – 15,000[68] Hungary – 15,000[68]

Hungary – 15,000[68] Singapore – 15,000[64]

Singapore – 15,000[64] Indonesia – 13,000[54]

Indonesia – 13,000[54] Ireland – 12,475 (2006)[74]

Ireland – 12,475 (2006)[74] Libya – 11,000[54]

Libya – 11,000[54] Venezuela – 11,000[54]

Venezuela – 11,000[54] Argentina – 10,552 [68]

Argentina – 10,552 [68] Peru — 10,409 (2017)[75]

Peru — 10,409 (2017)[75] Chile – 10,000[68]

Chile – 10,000[68] Portugal – 9,794[76]

Portugal – 9,794[76] Denmark – 9,634 (2018)[77]

Denmark – 9,634 (2018)[77] Czech Republic – 9,510 (2019; 7,131 have residence permit for 12+ months)[78]

Czech Republic – 9,510 (2019; 7,131 have residence permit for 12+ months)[78] Norway – 8,013 (2012)[79]

Norway – 8,013 (2012)[79] Malaysia – 8,000[64]

Malaysia – 8,000[64] Ecuador – 7,500[68]

Ecuador – 7,500[68] South Africa – 7,000[54]

South Africa – 7,000[54] Honduras – 7,000[54]

Honduras – 7,000[54] Romania – 6,000[54]

Romania – 6,000[54] Egypt – 6,000[54]

Egypt – 6,000[54] Trinidad and Tobago – 6,000[54]

Trinidad and Tobago – 6,000[54] Jamaica – 6,000[54]

Jamaica – 6,000[54] Finland – 5,576[80]

Finland – 5,576[80] Guatemala – 5,417 (2010)[81]

Guatemala – 5,417 (2010)[81] Belize – 5,000[54]

Belize – 5,000[54] Bolivia – 5,000[54]

Bolivia – 5,000[54] El Salvador – 5,000[54]

El Salvador – 5,000[54] Portugal – 4,768 (2022)[82]

Portugal – 4,768 (2022)[82] Qatar – 4,000[54]

Qatar – 4,000[54] Thailand – 4,000[54]

Thailand – 4,000[54] Nicaragua – 4,000[54]

Nicaragua – 4,000[54] Bermuda – 4,000[54]

Bermuda – 4,000[54] Malta – 4,000[54]

Malta – 4,000[54] Antigua and Barbuda – 3,000[54]

Antigua and Barbuda – 3,000[54] Uruguay – 3,000[83]

Uruguay – 3,000[83] Cayman Islands – 3,000[54]

Cayman Islands – 3,000[54] Jordan – 3,000[54]

Jordan – 3,000[54] Russia – at least 2,008[84] up to 6,200[85]

Russia – at least 2,008[84] up to 6,200[85] Ukraine – 3,000[54]

Ukraine – 3,000[54] Luxembourg – 3,000[54]

Luxembourg – 3,000[54] Cyprus – 3,000[54]

Cyprus – 3,000[54] Greece – at least 2,000[54]

Greece – at least 2,000[54] Paraguay – 2,000[54]

Paraguay – 2,000[54] Vietnam – 3,000[54]

Vietnam – 3,000[54] Bulgaria – 3,000[54]

Bulgaria – 3,000[54] Albania – 2,000[54]

Albania – 2,000[54] Croatia – 2,000[54]

Croatia – 2,000[54] Morocco – 2,000[54]

Morocco – 2,000[54] Haiti – 2,000[54]

Haiti – 2,000[54] Mali – 2,000[54]

Mali – 2,000[54]

See also

[edit]- Immigration to the United States

- Lost Generation

- Taxation of non resident Americans

- American Citizens Abroad

- Taxation of United States persons

- International taxation

- Relinquishment of United States nationality

- Samaná English

- List of Americans who married international nobility

- African-American diaspora

Diaspora by host country

[edit]- Americans in India

- American Canadians

- American Mexicans

- Americans in Cuba

- American Brazilians

- Americans in the United Kingdom

- American Australians

- American New Zealanders

- Americans in France

- Americans in the Philippines

- Americans in Japan

- Americo-Liberian people

- Sierra Leone Creole people

- Americans living in Saudi Arabia

- American settlement in the Philippines

- Mexicans of American descent

- Confederados of Brazil

- Americans in Haiti

- Americans in Costa Rica

- Americans in Germany

- Americans in the United Arab Emirates

- Americans in Uruguay

- Americans in Ireland

- Americans in Qatar

- Americans in Taiwan

- Americans in China

- Americans in Guatemala

References

[edit]- ^ The Loyalists Archived 2021-07-09 at the Wayback Machine, UShistory.org.

- ^ The Book of Negroes Archived 2022-07-30 at the Wayback Machine, Black Loyalists.

- ^ a b Walker, James W. (1992). "Chapter Five: Foundation of Sierra Leone". The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 94–114. ISBN 978-0-8020-7402-7. Originally published by Longman & Dalhousie University Press (1976).

- ^ The American Confederacy is still alive in a small Brazilian city called Americana Archived 2021-01-24 at the Wayback Machine, Business Insider, May 7, 2017.

- ^ Oxford and the Rhodes Scholarships Archived 2018-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, Rhodes Trust, Office of the American Secretary.

- ^ Mary Granfield (August 6, 1990). "Hiroshima's Lost Americans". People. Time Inc. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

n the summer of 1945, there were 30,000 Japanese-Americans in Japan. Many were kibei, American-born children whose immigrant parents had sent them back to Japan before the war to receive a traditional education. Others had come to visit relatives. After the war broke out in 1941, they were unable to return to the U.S.; 110,000 of their American relatives, most of them on the West Coast, were confined in internment camps.

- ^ "President Carter pardons draft dodgers". History.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Patty Winsa (February 8, 2015). "More U.S. soldiers could be sent back for court martial on desertion charges". The Star. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Edward Snowden: Leaks that exposed US spy programme". BBC. January 17, 2014. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Anna Robaton (November 20, 2013). "Feeling pinch back home, U.S. retirees pursue the American Dream abroad". CNBC. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Jonathan House (October 6, 2014). "Americans Don't Fancy Jobs Abroad. Oh, Except Millennials". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Record Numbers of Americans Want to Leave the U.S." Gallup. January 4, 2019. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Van Dam, Andrew (December 23, 2022). "Analysis | Why have millions of Americans moved to these countries instead?". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Record numbers of wealthy Americans are making plans to leave the U.S. after the election". CNBC.

- ^ Americans Abroad: Escaping or Enhancing Life? Archived 2021-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, UConn Today, August 7, 2020.

- ^ Dreaming of retiring abroad? Here's what you need to know Archived 2021-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, CNBC, September 14, 2020.

- ^ Many Americans move abroad for health care—should you? Archived 2021-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, MarketWatch, March 12, 2019.

- ^ Ghana to black Americans: Come home. We'll help you build a life here. Archived 2021-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post, July 4, 2020.

- ^ Joe Costanzo, Amanda Klekowski von Koppenfels (May 17, 2013). "Counting the Uncountable: Overseas Americans". Migration Policy Institute. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Entry and residence Archived 2021-05-09 at the Wayback Machine, Governor of Svalbard.

- ^ Immigrants warmly welcomed Archived 2019-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, Al Jazeera, July 4, 2006.

- ^ "Erleichterte Einbürgerung für Nachfahren von Nazi-Opfern". August 4, 2020. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ "Angehörige von Nazi-Verfolgten dürfen Deutsche werden - Politik - SZ.de". August 29, 2019. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Chapter 16, Temporary entry for business persons Archived 2021-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, Agreement between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada, Office of the United States Trade Representative.

- ^ "Estimation of emigration from the United States using international data sources" (PDF). UN Stats. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 5, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Why More Americans Are Renouncing U.S. Citizenship". NPR. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ 2020 is a record year for Americans giving up citizenship, according to N.Y. accountants group Archived 2021-01-24 at the Wayback Machine, Penn Live, October 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "The American Diaspora". Esquire. September 26, 2008. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Costing More Over There" Archived 2017-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist, 22 June 2006, accessed 17 April 2011

- ^ Leckie, Gavin F. (November 2011). "The Accidental American". Trusts & Estates: 58. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ Hildebrandt, Amber (January 13, 2014). "U.S. FATCA tax law catches unsuspecting Canadians in its crosshairs". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ Richard Rubin. "Americans Living Abroad Set Record for Giving Up Citizenship". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on August 4, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (February 9, 2017). "Boris Johnson among record number to renounce American citizenship in 2016". the Guardian. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Americans Forfeiting Citizenship at Record Rates With No Tax Relief in Sight". Fortune. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Millward, David (February 11, 2017). "Number of Americans renouncing citizenship reaches record high". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Stats" (PDF). unstats.un.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "CA By the Numbers" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. January 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2016.

- ^ Bill Masterson (2000), How Many Americans Really Live in Mexico? And Who Cares, Anyway?, peoplesguide.com, archived from the original on May 24, 2019, retrieved August 21, 2009

- ^ Overseas Citizen Population Analysis Report Archived 2021-01-24 at the Wayback Machine, Federal Voting Assistance Program. "In previous years, the Department of State has released estimates of the number of overseas civilians; however, these numbers are used for contingency operations and appropriately result in an overestimation."

- ^ 2018 Overseas Citizen Population Analysis Report Archived 2020-12-03 at the Wayback Machine, Federal Voting Assistance Program, July 2020.

- ^ 2016 Overseas Citizen Population Analysis Report Archived 2021-01-11 at the Wayback Machine, Federal Voting Assistance Program, September 2018.

- ^ "Overseas". FVAP.gov. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ International migrant stock 2019 Archived 2019-09-17 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- ^ These are our Numbers: Civilian Americans Overseas and Voter Turnout Archived October 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, By Dr. Claire M. Smith (Originally published: OVF Research Newsletter, vol. 2, issue 4 (Aug), 2010)

- ^ Table 2. Individual Income and Tax Data, by State and Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2018 Archived 2021-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, Internal Revenue Service, August 2020.

- ^ Table 1. Individual Income Tax Returns With Form 2555: Sources of Income, Deductions, Tax Items, and Foreign-Earned Income and Exclusions, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2016 Archived 2021-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, Internal Revenue Service, October 2019.

- ^ Table 5. Individual Income Tax Returns With Form 1116: Foreign-Source Income, Deductions, and Taxes, by Type of Income, Tax Year 2016 Archived 2021-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, Internal Revenue Service, October 2019.

- ^ "Table 1: Total migrant stock at mid-year by origin and by major area, region, country or area of destination, 2017". United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics (May 8, 2013). "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables – Citizenship (5), Place of Birth (236), Immigrant Status and Period of Immigration (11), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Fact Sheet: The United States and India — Prosperity Through Partnership". whitehouse.gov. June 26, 2017. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2017 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Why the Philippines Is America's Forgotten Colony". Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ "Toasts of the President and President Walter Scheel of the Federal Republic of Germany During a Dinner Cruise on the Rhine River. | The American Presidency Project". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ US Embassy in Brazil Archived 2020-07-13 at the Wayback Machine US Embassy in Brazil. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". migrationpolicy.org. February 10, 2014. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ 2013 - Office for National Statistics

- ^ "U.S. Citizen Services". Embassy of the United States Seoul, Korea. United States Department of State. Archived from the original on November 30, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

This website is updated daily and should be your primary resource when applying for a passport, Consular Report of Birth Abroad, notarization, or any of the other services we offer to the estimated 120,000 U.S. citizens traveling, living, and working in Korea.

"North Korea propaganda video depicts invasion of South Korea, US hostage taking". Advertiser. Agence France-Presse. March 22, 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2013.According to official immigration figures, South Korea has an American population of more than 130,000 civilians and 28,000 troops.

[permanent dead link] - ^ No. of Foreign Nationals Residing in Korea Exceeds 2 Mil. in 2016 No-of-foreign-nationals-residing-in-korea-exceeds-2-mil-in-2016 (The Korea Economic Daily) Archived 2017-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Costa Rica". Archived from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ "Australia's Population by Country of Birth". Australian Bureau of Statistics. April 26, 2022. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ "Résultats de la recherche - Insee". insee.fr. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ "Census counts Japanese in the US". Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ 2010 Chinese Census (from Wikipedia article Demographics of the People's Republic of China)

- ^ a b c d "US citizens in rush for offshore tax advice". Financial Times. September 8, 2009. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ "United States - International emigrant stock 2020 | countryeconomy.com". countryeconomy.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2022. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Gishkori, Zahid (July 30, 2015). "Karachi has witnessed 43% decrease in target killing: Nisar". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

Besides Afghans, 52,486 Americans, 79,447 British citizens and 17,320 Canadians are residing in the country, the interior minister added.

- ^ "CBS StatLine". statline.cbs.nl. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". February 10, 2014. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ see List of countries with foreign nationals in Lebanon

- ^ U.S. Relations With Panama, archived from the original on June 4, 2019, retrieved May 25, 2019

- ^ Vidal, Roberto (2013). "Chapter III: Public Policies on Migration in Colombia" (PDF). In Chiarello, Leonir Mario (ed.). Public Policies on Migration and Civil Society in Latin America: The Cases of Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico (PDF) (1st ed.). New York: Scalabrini International Migration Network. pp. 263–410. ISBN 978-0-9841581-5-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ "2006 Census, Statistics New Zealand". Archived from the original on July 24, 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 24, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ File:NonnationalsIreland2006.png

- ^ Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (October 2018). "Perú: Estadísticas de la Emigración Internacional de Peruanos e Inmigración de Extranjeros, 1990 – 2017" (PDF). Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM). 1. Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores - RREE: 85. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020 – via Database.

- ^ "Relatório de Imigração, Fronteiras e Asilo 2022" (PDF).

- ^ "Statistikbanken". statistikbanken.dk. Archived from the original on August 28, 2004. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Foreigners, total by citizenship as at 31 December 2018 1) Archived 9 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Czech Statistical Office.

- ^ "Table 4 Persons with immigrant background by immigration category, country background and gender. 1 January 2012". Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ "Väestö 31.12. muuttujina Maakunta, Syntymävaltio, Ikä, Sukupuoli, Vuosi ja Tiedot". Tilastokeskuksen PX-Web tietokannat. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ (in Spanish) Perfil Migratorio de Guatemala Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM) (2012)

- ^ "Resident Foreign Population in Portugal - United States of America". Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ "Immigration to Uruguay" (PDF) (in Spanish). INE. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 16, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ Russian Census (2002), Basic Result Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine: table 4.1. National composition of population Archived 2011-06-09 at the Wayback Machine, table 4.5. Population by citizenship Archived 2011-06-09 at the Wayback Machine, table 8.3. Population stayed temporarily on the territory of the Russian Federation by country of usual residence and purpose of arrival

- ^ Federal State Statistics Service, table 5.9. International Migration: in Russian Archived 2011-06-28 at the Wayback Machine, in English

External links

[edit]- The American Diaspora, Esquire, 26 September 2008.

- Jones, Chris. The New American. Esquire, 23 September 2008.

- Sappho, Paul. A Looming American Diaspora, Harvard Business Review, 2009.

- Sullivan, Andrew. The New American Diaspora The Atlantic, 29 September 2009.

- Go East Young Moneyman, The Economist, 14 April 2011.

- William Curtis Donovan. The Coming American Diaspora, 1 October 2008.