Anderitum (Gaul)

ad Gabalos (~ 300) | |

Cold pool at the Western thermal baths | |

| Location | Roman Empire |

|---|---|

| Region | Peyre en Aubrac, Lozère, Occitania |

| Coordinates | 44°41′42″N 3°20′36″E / 44.69500°N 3.34333°E |

| Type | Civitas capital |

| Site notes | |

| Protected as French historical monument (1954, 1991)[1] | |

Anderitum, known as ad Gabalos in the late 3rd century and as Javols in subsequent centuries, is a Gallo-Roman town located in the French department of Lozère, within the current territory of the commune of Peyre-en-Aubrac. It functioned as the capital of the civitas of the Gabali from the late 1st century BC until approximately the 5th century AD.

Anderitum was probably established following a scattered La Tène culture settlement that extended beyond the ancient town's site. It was probably founded during the reign of Augustus in the last two decades of the 1st century BC, like many civitas capitals. By the 2nd century, the town reached its peak, covering approximately 40 hectares with a population of several thousand inhabitants. It included several residences, three identified domus, an amphitheater or possibly a theater-amphitheater, two thermal establishments, and a civic center with a forum, a curia, and a basilica. The urban layout followed an orthogonal street grid. However, its peak was short-lived, and the town began to decline as early as the following century, making Anderitum one of the "ephemeral capitals" of Roman Gaul. The capital was later moved to Mende in the Middle Ages, which increased its political and economic importance as the diocesan seat. Consequently, the ancient town of Anderitum gradually gave way to the village of Javols.

Archaeological explorations and excavations in the town's center started in the 19th century. The remains of Anderitum's monumental center were designated as historical monuments in 1954, with the entire site receiving protection in 1991. Landscape enhancements have recreated the street layout of the agglomeration, and restoration work on key remains has enhanced the visitor experience. Virtual reality technologies provide a reconstruction of the ancient town.

Toponomy[edit]

The commonly accepted etymology of the toponym Anderitum among toponymists and Celtic linguistics specialists is based on two roots from Old Continental Celtic (Gaulish): ande + rito- with the Latin suffix -um. This would mean "in front of the ford" or rather "large ford," with ande (and-, ando) also being an intensive particle.[2] It is noted that the element ande also appears in the proper name "awning," Old Provençal amban, "advanced fortification work," and Languedocian embans "shop awning" from Gaulish *ande-banno-.[3] The element rito- "ford" (cf. Old Welsh rit > Welsh rhyd: ford) is frequently encountered in Gaulish toponymy. It explains certain endings in -or- (Jort, Gisors, etc.) and also some -roy or -ray (cf. Gerberoy, Longroy, Mauray, Mauroi) likely linked to its late survival in proto-Roman times in northern France.[4]

It is likely that towards the end of the 3rd century, the town's name appeared in the syntagma ad Gabalos, evolving into the Occitan Gaboul by the 13th century,[F 1] simply meaning "the town of the Gabales." This naming phenomenon was common in Roman Gaul, where the capitals of civitas adopted the name of the people. For example, Tours, formerly Caesarodunum, was renamed Turones, which means "among the Turons"; the same applies to Beauvais, Le Mans and Limoges, Périgueux.[F 2][5]

Historical and geographical context[edit]

Foundation as a political decision[edit]

Julius Caesar refers to Gabali's people as "clients" of the Arverni in Commentaries on the Gallic War (VII, VII, 2 and VII, LXXV, 2).[B 1] Augustus' choice to establish the civitas of the Gabales on the outskirts of the Arverni territory and designate Anderitum as its capital was probably intended to weaken this reliance and reduce the geographical and demographic significance, and consequently the political influence, of the Arverni.[F 3]

The identification of Anderitum with Javols has been widely accepted since the 20th century, but this was not always the case. In the 1820s, Charles Athanase Walckenaer argued that Anderitum had become Anterrieux in Cantal.[7] However, the debate was settled in 1828 with the fortuitous discovery of a milestone while searching for stones to restore the church.[8][9] The milestone bears the inscription: "Under the reign of Emperor Caesar Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus, invincible, pious, fortunate, Augustus, high priest, endowed with tribunician power, father of the country, four times consul, the city of the Gabales".[10] Such a dedication, collectively "signed" by the civitas, can only be conceived in its capital.[T 1]

Important road junction[edit]

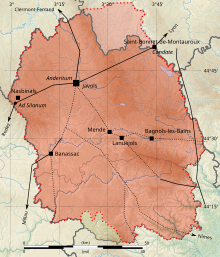

The town of Anderitum is listed on the Peutinger map between the stations of Condate (Pont de Vabres west of Alleyras) to the northeast and Ad Silanum (Puech Crémat-Bas south of Nasbinals) to the southwest, along the road connecting Reuessione (Ruessium/Saint-Paulien) to Segoduni (Segodunum/Rodez).[B 2] The name Anderitum is also mentioned by Claudius Ptolemy as Andérèdon (Άνδέρηδον) in the 2nd century (Geography, II, 7, 11) and by the Ravenna Cosmography as Andereton in the 7th century (Cosmographie, IV, 26).[B 1]

Anderitum was a crucial junction on the route from Lugdunum (Lyon) to the Ruteni, with their capital at Segodunum. This road intersected at Anderitum with another axis running north-south, linking Clermont-Ferrand to Languedoc and the Mediterranean Sea.[F 4] Anderitum was the main settlement in the northern part of the Gabales civitas, serving as a hub for the road network.[B 3] Two potential roads could have connected Anderitum to Banassac and then Millau, as well as to Mende and Nîmes. Anderitum might have been strategically located at the crossroads of existing roads, or these roads could have been developed after the town's establishment.[C 1]

Valley surrounded by hills[edit]

The site is located in the widened valley of the Triboulin, a tributary of the Truyère, and extends up the surrounding hills, with altitudes ranging from 972 to 1,015 meters.[F 5] These topographical conditions led to the construction of terraces to accommodate some buildings,[11] either by excavating the natural substrate or by filling.[C 2] During antiquity, the Triboulin, flowing from south to north, was channeled through the site with the establishment of the "Javols quays." As the town declined, the river resumed its natural course; in modern times, the average level of the stream has risen by at least 1.5 meters compared to antiquity.[T 2] The seasonal regime of the river, characterized by torrential floods, likely required this arrangement. Additionally, fossil pre-Roman channels observed in the monumental center indicate that the course of the Triboulin has naturally shifted over the centuries.[C 3]

The area around Anderitum was mostly deforested during the La Tène period. In ancient times, mixed forests, meadows, and fields for growing cereals and vines existed.[F 6] The wood used, probably cut down locally, included common beech, fir, and Scots pine, with some oak and hazel trees.[T 3]

History[edit]

Pre-Roman occupation[edit]

The occupation of the Anderitum region until the Iron Age is evidenced by stone tools from the Paleolithic (rough hand axe) or Neolithic (flint tools)[T 4] and by a combustion structure on the site's western heights (Late Neolithic-Chalcolithic).[12]

The Bronze Age and Hallstatt periods are poorly documented, with more substantial evidence appearing during the La Tène period when the site was permanently settled. The exact nature and extent of this occupation, which is evident from the 2nd century BC, still needs to be defined. It was not a significant oppidum that could function as a "capital",[N 1] but rather a collection of dispersed settlements on the surrounding heights, including one on Barry Hill to the south, likely of a cultic nature. Moreover, the presence of Gallic and Republican coins,[F 7] fragmented ceramic shards,[N 2] and Italic amphorae suggests a fairly extensive and consistent occupation of the plain.[C 4] Some artifacts may have been washed down from the hills into the valley. Peri-urban sites also indicate La Tène occupation that persisted until at least the 3rd century AD.[T 6]

Augustan foundation[edit]

The Roman establishment of Anderitum as a planned town probably occurred during the reign of Augustus, around 15 BC, which was a common practice for many civitas capitals at that time. This coincided with the emperor's third visit to Gaul.[14] Archaeological findings such as road segments and numerous dupondii coins from Nîmes support this dating. However, there is limited knowledge of the buildings from that era, with only a few architectural remnants found and reused in later constructions.[C 5] The reason for selecting a peripheral location within the civitas territory remains unclear.[F 8]

A few years later, at the beginning of our era, a part of the urban grid was established, including the civic center (forum, curia), private homes, and drainage operations to reclaim a marshy area on the left bank of the Triboulin. Although based on somewhat limited evidence, this chronology would place Anderitum in line with many other towns in Gaul.[T 7]

Peak during the Early Empire[edit]

A significant phase of urbanization occurred in the second half of the 1st century during the Flavian dynasty. This period saw the enhancement of the street network, the construction of the first public buildings (western baths), and the development of numerous private residences. Granite quarries located on the outskirts of the town were utilized to provide construction materials, and at least one of the two known necropolises was established during this time. This progression is characteristic of many Gallo-Roman towns.[T 8]

During the 2nd century, the first buildings in Anderitum were either rebuilt or renovated (such as the civic center and western baths), while new constructions (the eastern baths and private buildings) were also added. Artisan workshops began operating within the town and its outskirts, and an urban dump was established.[T 9] This period marked Anderitum's peak,[F 9] likely corresponding to the reigns of Hadrian and Antoninus Pius.[15] The capital of the civitas of the Gabales may have covered 35 to 40 hectares, with 5.8 hectares densely built and organized on the left bank of the Triboulin.[F 7] The population of Anderitum could have reached a few thousand inhabitants.[T 10]

Contraction during the Late Empire[edit]

Gradual decline[edit]

By the end of the 2nd century, the town began to decline. Buildings in both the center and the periphery seemed to have suffered from fires between the late 2nd century and the late 3rd century. These fires, likely accidental and unrelated to "migration period" (which were never attested in Anderitum, contrary to claims by 19th-century scholars[16]), damaged or destroyed buildings, most of which were not rebuilt or were restored more modestly.[T 11] This trend was also evident in peri-urban settlements: the storage room of a domus in the Barry area, destroyed (also by fire) in the early 2nd century, was not rebuilt. The town's footprint decreased from the 3rd century onwards. The theater-amphitheater was destroyed or repurposed by the end of the 3rd century.[17] However, the town did not completely "die," and signs of urban activity, such as the maintenance of main streets and residential areas, persisted until the 5th century. Evidence does not support the idea of a sudden and massive abandonment followed by partial reoccupation of the town after the fires of the 2nd and 3rd centuries.[D 1]

Transfer of powers from Javols to Mende[edit]

A primitive church may have existed as early as the beginning of the 4th century.[F 10] However, unlike other civitas capitals, including its neighbor Rodez, Anderitum did not build an enclosure during the Late Empire.[T 12] The town's decline is linked to the transfer of the civitas capital to Mende, which was also elevated to an episcopal seat, probably around 530–540. Mende hosted an active pilgrimage to Saint Privat.[18] The exact chronology of this shift and its impact on Anderitum are still poorly understood; Banassac may have temporarily served as the episcopal seat after Javols and before Mende.[19]

Disappearance of the Ancient City[edit]

The town's history is not extensively documented from the Early Middle Ages. The urban center's footprint decreased, with peripheral occupations gaining prominence. The lower part, near the stream, saw urban abandonment from the 6th century onwards, with archaeological evidence suggesting a shift to agricultural activity, indicated by the presence of dark soils.[F 11] One reason for this change was the increased flood risk in the Triboulin Valley from the 6th century. Local tradition even speaks of the town being "submerged" by a dragon.[20] Subsequently, the ancient site vanished from the urban landscape, and the town relocated to the southwest.[F 12] The ruins were likely used as stone quarries, while pine forests gradually reclaimed previously cultivated areas on the slopes.[C 6]

Romanization of an ephemeral capital[edit]

Roman acculturation influenced the town's design, architecture, and the lifestyle of its inhabitants, with the timing and extent of this phenomenon varying across different areas.[T 13]

The foundation of the Augustan town, the orthogonal plan of its monumental center, and its public buildings reflect a strong influence of Latin customs. It is challenging to gauge the impact of Roman religion on local practices due to the limited archaeological evidence available.

Epigraphic inscriptions are rare and fragmentary; however, the discovery of numerous metal styles, several fir wood tablets, and the variety of graffiti on pottery indicate that writing was used regularly and extensively by the inhabitants of Anderitum.[C 7] The gradual evolution of domestic habits, such as food, tableware, hygiene, and clothing, suggests that "Gallic" traditions persisted for a significant period. A "Roman" lifestyle adoption, including nailed-soled shoes, clothing fastened with fibulae, use of oil lamps, three-legged cooking pots, kitchen lids, and beef consumption, only became prevalent in the second half of the 1st century. The scarcity of fibulae in the region may be attributed to the local climate, which favored "Gallic-style" sewn garments.[C 7]

However, the Romanization of Anderitum did not prevent it from losing its status as a civitas capital, like about forty others out of approximately sixty,[21] as a result of Augustus's administrative organization of Gaul. None of these "ephemeral capitals" constructed a defensive enclosure during the Late Empire, indicating that their decline was already well underway and considered irreversible. While the exact causes remain unknown, Anderitum's decline was likely due to a combination of religious factors (loss of the bishopric), political factors (lack of a strong local leader), and climatic influences (the "Little Ice Age" of late antiquity),[22] with the latter having more severe effects in a mid-mountain region.[T 14]

Archaeological excavations, studies, and site development[edit]

Chronological markers[edit]

| -300 — -200 | the beginning of La Téne occupation? |

|---|---|

| -100 — -30 | Attested occupation on the site |

| -17 — -13 | Foundation of Anderitum |

| 50 — 100 | First phase of urbanization |

| 117 — 161 | Anderitum Apogee |

| 190 — 210 | Fire? |

| 300 | |

| 290 — 310 | Modification of the theater? |

| 280 — 300 | Anderitum becomes ad Gabalos |

| 300 — 320 | First church? |

| 300 — 410 | Partial reconstruction |

| 530 — 540 | Church transfer? |

| Construction phase Destruction phase Anderitum/Javols event history(Dates before Jesus Christ are mentioned negatively: -100 corresponds to 100 BC.) | |

The site and its ancient origins have been recognized since the 17th century, as noted by Jean-Baptiste L'Ouvreleul in 1724–1726, referring to the "Roman quays".[23] In 1753, Jean-Aymar Piganiol de La Force established the connection between Anderitum, the Gévaudan bishopric, and Javols, mentioning the ancient ruins and artifacts (medals and urns).[24] The first archaeological studies began in 1828 after the discovery of a milestone. This discovery, which seemed to be part of a systematic search for reused blocks to repair buildings, indicates the enduring memory of a monumental town that could have served as a quarry.[25] Research continued throughout the 19th century, with a pause of three decades before excavations resumed just before World War II. Unfortunately, most of the documentation from this period has been lost.[N 3] Excavations were also carried out in 1950, leading to the construction of a small museum. Two significant projects were conducted from 1969 to 1978 and from 1987 to 1994. Some rescue operations were undertaken in the early 1990s, with a focus on Anderitum's monumental center.[F 13]

In 1996, a collaborative research program was established. Led by Alain Ferdière and Benoît Ode from 1996 to 2004, and later by Alain Trintignac from 2005 to 2010,[27][28] the training excavation integrated historical and archaeological evaluations by re-examining existing sources and conducting surveys and excavations.[F 14] Since 2010, sporadic observations have been ongoing during rescue archaeological operations.[29]

The Javols Archaeological Museum was established in 1988.[30] In 2012, the Languedoc-Roussillon region, which owns part of the site, initiated landscape enhancement projects at the monumental center to improve the visitor experience.[25] Recently, visitors can explore the site with augmented reality glasses that recreate the ancient buildings' location and appearance.[31] Additionally, a 3D reconstruction of the town is available on the CITERES website, which is a joint research unit of CNRS and the University of Tours.[32]

Specificities of the excavation sites in Javols[edit]

Previous excavations, dating back to the 1970s, were not carried out using methods and resources that would ensure complete confidence in their findings. Furthermore, the artifacts unearthed during these excavations are either scattered or lost.[33] The highly acidic nature of the soil hastens the deterioration of calcareous archaeological materials (construction stones, pottery, and bones). The thick layer of colluvium that has accumulated at the base of the hills since ancient times significantly hinders aerial survey capabilities, while the erosion caused by the colluvium phenomenon affects the substructures in the upper parts of the site. The presence of shallow groundwater in the monumental center poses a significant challenge to conducting deep or long-term excavations. These unique conditions contribute to an irreversible loss of archaeological data.[T 15]

On the other hand, the abundance of colluvium protects the remains in their lower parts, and the elevation of some structures is sometimes preserved up to a height of 2 meters.[D 3] Additionally, the absence of recent constructions above the archaeological remains facilitates access to older strata, which are better preserved from disturbances.[F 2][T 15]

Anderitum in Antiquity[edit]

Roads and urban planning[edit]

At its peak, the town covered around forty hectares, but only a little less than 6 hectares in the flat part of the Triboulin Valley were organized with an orthogonal street plan. In this way, two decumani are documented, four to five others are assumed, and three cardines may take their place, the existence of one of them being a mere hypothesis. Based on recent research, none of these roads can be definitively identified as the city's main axis (decumanus maximus and cardo maximus). Beyond this grid, the roads follow the natural land contours, weaving between the various elevations surrounding Anderitum.[F 15] The town's boundaries (pomerium) do not appear to be delineated by an enclosure or ditch.[T 16][T 17]

The development of the two banks of the Triboulin ("Javols quays") includes large granite blocks arranged in at least four superimposed rows, channeling the stream to a width of 11 meters in the southeastern part of the settlement. The granite blocks are connected by iron clamps sealed with lead.[D 3] This arrangement aims to redirect the watercourse eastward and increase the buildable area. The term "quays" may be misleading as the Triboulin likely did not allow navigation that would require a real dock.[34] One or two fords, which give their name to the site, may have been constructed on the stream, possibly to the north or southwest, to ensure the continuity of traffic routes.[N 4] A bridge over the Triboulin could extend the "central" cardo in line with the theater.[F 16]

Public monuments[edit]

Public monuments were primarily constructed using small granite rubble masonry. Large blocks were reserved for specific purposes such as cornerstones, thresholds, and foundation walls. The use of "noble" materials, such as limestone, schist and marble, was typically limited to public monuments. The floors of these structures were often paved with limestone, which was frequently salvaged when the monument fell into disuse.[C 8]

Civic center[edit]

The existence of a forum in Anderitum was only confirmed in the late 1990s through excavations and aerial surveys, as the traces were visible for a brief period. Likely constructed in the Augustan era,[C 9] the forum appears as a 70 x 50-meter space open to the north, surrounded on at least two sides by porticoes and shops. To the north would be the curia, with a honeycomb mosaic on the floor in one of its states, opening onto the forum through a monumental door.[35]

In the 2nd century, the entire complex underwent extensive remodeling.[T 9] The forum was expanded to the south and east, while to the north, the building identified as the curia was intersected by the construction of a basilica that obstructed the north end of the forum,[F 17] with an estimated size of 50 × 23 meters.[T 18] A road (decumanus) may have separated the basilica from the forum.[C 9]

Entertainment building[edit]

The remains of an entertainment building are buried on the slope and at the bottom of Barry (or Barri) hill, overlooking Anderitum to the south on the right bank of the Triboulin. Its existence has been suspected since the mid-19th century due to observations of "semi-circular slopes".[D 4] The nature of the remains is still debated, with suggestions that it could be an amphitheater or more likely a mixed building with an incomplete cavea and a circular arena. In the first hypothesis, the southern part of the amphitheater is massive, backed against the hill, while the northern part is built on masonry vaults. In the second hypothesis, the cavea rests entirely on the hillside, with only the stage building constructed in elevation.[C 10] In either case, the monument's largest dimension does not exceed 80 meters.[F 18] Part of the outer wall of this building was uncovered during excavations in 2012.[29] If the entertainment building of Anderitum is a theater-amphitheater rather than a complete cavea amphitheater, this layout is not unprecedented, as other civitas capitals adopted similar designs. However, the limited available evidence would rather compare the Anderitum building to the Lillebonne theater.[T 19]

The construction may date back to the second half of the 1st century.[T 20] In the second half of the 3rd century, it was destroyed, at least in its upper parts, or repurposed for civic use.[C 10] A milestone dedicated to Emperor Postumus now occupies the center of its arena.[F 19]

Baths[edit]

Two bath complexes, likely public due to their large size, are attested at Anderitum. Recent studies indicate there are no private bathing facilities at the site.[C 11]

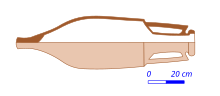

The Western Baths have been known since the mid-19th century. At the time of the excavations, 43 rooms were reported,[D 5] but it is possible that several successive states overlapped, and the actual number of these rooms may be more limited. A cold pool and a room heated by hypocausts are still identifiable. The 19th-century excavations mention the water supply by several aqueducts, imprecisely located, but no recent observations have found traces of them.[F 20]

The eastern baths were uncovered during a collaborative research project. The structure, aligned with the city's grid rather than the nearby river, was established around the mid-1st century and underwent multiple renovations until the 2nd century. It comprises various rooms following the standard Roman bath design: frigidarium, tepidarium, caldarium, and praefurnium. The cold pool's apse is supported by the blocks of the "quays".[C 11] Water is sourced from a well and possibly from the Triboulin.[F 20]

Other public facilities[edit]

Along the eastern cardo of the city, archaeologists uncovered the facade and monumental entrance of an unidentified building. Although the function of this structure, possibly a schola of a college, cannot be definitively determined, its status as a public institution is evident.[T 21]

The water supply system in Anderitum is not well understood, but it is believed to have several aqueducts. One aqueduct is thought to come from Cros Hill to the northwest, another from the east (L'Oustal Neuf) near the baths, and a pipeline from the southwest heading towards the city.[T 22] A public fountain at the intersection of two roads in the monumental center may be supplied by the first aqueduct.[B 4] Additionally, at least seven wells, estimated to be 3 to 7 meters deep, have been found,[T 23] suggesting that wells, sources near the city, and direct withdrawal from the Triboulin may be the main water sources.[T 22][C 12] Various sewers, with floors made of schist slabs or tegulae and vertical stone walls, are identified or assumed in different parts of the settlement, such as the entertainment building and the monumental center.[T 24]

The presence of structures for storing food is essential. A poorly characterized building, likely built around the mid-1st centurmiddle of the 1st century parallel to the western development of the Triboulin bank, could have served as horrea.[T 25] The presence of one or more rooms heated by hypocausts may not necessarily be incompatible with this function.[C 13]

Private dwellings[edit]

Remains of private dwellings have been identified at several points in Anderitum, both in the organized central area and in more distant sectors. Although the discovered remains are rare, the harsh winters of Aubrac likely necessitated the installation of hypocaust heating or wall fireplaces in rooms of dwellings that would not require them in other climates.[C 14] The walls of private dwellings typically consist of two facings in small granite blocks with, occasionally, beds of tiles (opus mixtum) enclosing a very thin Roman concrete. Large granite blocks, likely sourced on-site during construction, are frequently incorporated into the masonry. The roofs are likely tiled or made of perishable materials such as thatch or wood shingles; schist slab coverings are not currently known to have been used.[C 15]

In three situations, there are enough elements to reconstruct a domus, two in the "downtown" area and one outside; they have also undergone thorough, even complete excavations.

At the intersection of a cardo and a decumanus, south of the current cemetery, there is a large complex consisting of three or four buildings, some terraced, arranged around a central courtyard. The complex includes a basin on one side and likely shops opening onto the decumanus. This complex is known as the "Peyre domus," named after Abbé Pierre Peyre, a CNRS researcher who excavated this area in the 1970s without fully identifying the discovered remains. The construction of the complex took place around the mid-1st century and underwent several phases before being destroyed at the beginning of the 3rd century.[F 21]

In the northern part of a densely urbanized area, there is a large house with numerous comfort facilities including several ovens, a fireplace, a complex water drainage, and evacuation system. The initial construction phase appears to date back to the Augustan period, followed by several renovations, possibly due to a fire in the 3rd century. During the Late Empire, only a modest building was reconstructed.[F 22]

On the right bank of the stream, 200 meters south of the entertainment building, several buildings are arranged around a central courtyard. One of the buildings is built on a terrace carved into the granite substrate. These buildings may be part of one or two domus.[C 16] The construction and modifications of the complex date from the early 1st century to the early 3rd century.[F 21]

Cult sites and necropolises[edit]

Private cults confirmed but public sanctuaries to be discovered[edit]

Ancient and recent research does not definitively pinpoint the location of any sanctuary or temple during Anderitum's active period. Several hypotheses suggest possible locations such as the modern cemetery, the center of the forum, or the basilica, but none are supported by solid archaeological evidence. However, on Barry Hill to the south of the site, a La Tène structure followed by votive deposits from the 1st century BC may indicate the presence of a sanctuary in the vicinity.[T 26] A statue of the god Silvanus-Sucellus was unearthed during excavations in the late 1960s, likely not in its original location.[T 27] Crafted from red sandstone sourced from Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole,[C 17] the statue, standing at 1.76 meters tall,[36] depicts Silvanus-Sucellus, possibly revered as the patron of woodworkers, coopers, or wine merchants,[T 28] as suggested by the amphora and barrel depicted on the statue.[37] Numerous terracotta figurines, predominantly portraying Venus or mother goddesses, including one well-preserved figure nursing two children, were likely produced locally or imported from the Iberian Peninsula between the 1st and early 3rd centuries. These figurines, discovered mainly in late filling deposits dating to the Late Empire or Early Middle Ages, indicate the presence of domestic cults in Anderitum.[38]

Necropolises at the city limits[edit]

Two necropolises have been identified for the Early Empire in Anderitum, dating back to the mid-1st century or shortly after. The burials consist mainly of cremations accompanied by funerary urns, with some inhumations also present. These necropolises are situated to the northwest and northeast of the city, outside the urbanized area, along or near a possible "detour" of the road from Lyon to Rodez. Their recent discovery in 2001-2002 confirms previous hypotheses about the city's northern limit.[T 29] A cippus dedicated to the memory of "Albinus Senator" is believed to originate from Anderitum, although the exact discovery site and dating remain unknown.[C 18]

To the southwest of the settlement, a necropolis with stone caisson burials was used from the mid-4th century to the 6th or 7th century. Another necropolis, likely associated with the first church of Javols, is located near the western baths during the Early Middle Ages and mainly consists of inhumations in the ground.[F 23][C 19]

Craft and trade[edit]

Production activities[edit]

The craft activities identified in Anderitum appear to be limited in significance and quantity; lead work has been documented. The presence of iron slag indicates that ironworking was conducted at the site, although the lack of iron ore nearby suggests that it may have been a final preparation step before use.[T 30] Copper alloy metallurgy appears to have been a more prominent feature of the city's economy, with two bronze workshops located in the city center.[39] Woodworking, evidenced by tools, utensils, carving waste, and the Silvanus-Sucellus statue,[T 27] likely plays a significant role in the city's economy. A jeweler's workshop, producing intaglios among other items, has been identified on the city outskirts.[T 29] The production of common gray ceramics and tiles is likely limited to the city's immediate needs.[F 24][40] Surprisingly, evidence of textile activity is scarce.[T 31]

Several millstones, often made of Volvic stone extracted in the Cantal, have been discovered. Most of them are small and meant for domestic use, but there are also larger ones that could only be operated by an animal or a hydraulic system, indicating that they may have been used as millstones for bakers.[T 32][T 33] While butchery activity has not been confirmed, it is considered probable based on the presence of bones that were either discarded or possibly worked into tablet-making accessories.[C 20]

Commercial exchanges[edit]

Massive ceramic imports began in the 1st century, with workshops in southern Gaul, particularly La Graufesenque, supplying Anderitum. Local tradition suggests a route connecting La Graufesenque to Banassac and Javols.[B 5] However, around 160-170 AD, the city started favoring regional productions (Ruteni and Gabali).[T 34] Despite the proximity of the terra sigillata workshop in Banassac, it did not seem to benefit from this shift, as its productions remained unknown at Anderitum.[C 21]

Granite and granitic grus resulting from its mineral alteration, and granulite were the primary construction materials for the city's buildings and infrastructure.[T 35] While these rocks were mainly sourced locally, resources from farther away were also utilized, particularly for decorative elements. Sandstone from Margeride, schist from the Cévennes, limestone from the Causses, porphyries from Djebel Dokhan (Hurghada region, Egypt) or the Peloponnese (Greece), Giallo antico from Chemtou (Tunisia), marbles from Synnada (Turkey), Carrara (Italy), or Morvan were among the materials used.[T 33]

Anderitum received a diverse range of food supplies, with over 350 amphoras discovered or reconstructed in the area. Approximately 40% of these containers, mainly Dressel 2–4, were used to transport Gallic wine, while others originated from Spain, Italy, and Rhodes. Additionally, containers for oil, alum, garum, salted seafood, and oysters were found in smaller quantities. Various cereals (wheat, barley, oats) and legumes (peas, lentils, and fava beans) were also present. Pine nuts were consumed along with meats including beef, mutton, goat, pork, and poultry, although the proportion of local production is uncertain.[T 36]

Immersive applications[edit]

The archaeological site of Javols-Anderitum, designated as a supplementary historic monument, is currently under the management of the Occitanie/Pyrénées Méditerranée Region,[41][42] which acquired ownership in 2009. In 2012, the region initiated a project to improve the site, intending to preserve the unearthed artifacts and revitalize the "Roman city" through landscaping and enhancements.[43]

2014[edit]

The community spearheaded a collaborative project to improve the archaeological site in partnership with the State, the Lozère Department, and the Hautes-Terres de l'Aubrac community of communes. The goal was to preserve, enhance, and pass on the historical and heritage aspects of the ancient capital of Gévaudan. Key features of this partnership included:

- Landscape developments include the incorporation of floral vegetation and a mineral substrate, which recreate the monumental core of the ancient city and its urban layout. The floral maintenance of the site was conducted by the rural forestry school of Javols.[44]

- Improving the permanent interpretation route, enhanced with educational support.[45]

2016[edit]

The Occitanie-Pyrénées Méditerranée Region, specifically the Directorate of Culture and Heritage and the Directorate of Information and Digital Systems, collaborated to create a permanent interactive route to showcase the history and heritage of the ancient city of Javols. The goal was to make this historical site more accessible to the public through innovative and immersive technology.[46]

This ambition was made possible thanks to the work done by the University of Tours (UMR CITERES) in designing a 3D model of the ancient city and acquiring an aerial view from the company L'avion Jaune.[47]

To develop this future device, a detailed specification was created to initiate a public tender for the development of the first version of the application using augmented reality technology. The project was structured to incorporate an innovative AGILE project approach, utilizing a participatory method focused on user experience and involving a panel of testers.

2017[edit]

Art Graphique et Patrimoine won the public tender to develop the "Javols 3D" application.[48][49][50] The device chosen for the project is a smartphone paired with the Samsung Smart Gear augmented reality headset, which was well received by the public during the design phase.

The application was launched in November 2017 and showcased at the Louvre Carousel in Paris during the International Heritage Days by the project team from the general services of the Occitanie-Pyrénées Méditerranée Region.[51]

A second version of the application was developed in late 2023, this time in collaboration with the company IGO as part of a public tender dedicated to 3D enhancement. This second version, still free and titled "Javols 360" is now available on various platforms.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ It is uncertain whether the Gabali had a settlement significant enough to establish itself as a capital before the Roman conquest.[T 5]

- ^ A non-wheel-thrown ceramic is shaped without using a potter's wheel.[13]

- ^ During World War II, Jean Lyonnet, the architect of historical monuments and one of the excavators, promptly joined the Resistance. In 1944, his home was searched while he possessed excavation notebooks and plans, forcing him to flee.[26][D 2]

- ^ There is no evidence to suggest that the fords if they did exist, predate the city's foundation, even though the name Anderitum is derived from pre-Roman roots.[F 7]

References[edit]

- Carte archéologique de la Gaule - La Lozère. 48, Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, 1989:

- ^ Fabrié 1989, p. 42

- ^ Fabrié 1989, p. 36

- ^ a b c Fabrié 1989, p. 34

- ^ Fabrié 1989, p. 39

- ^ Fabrié 1989, pp. 34–35

- Une petite ville romaine de moyenne montagne, Javols/Anderitum (Lozère), chef-lieu de cité des Gabales: état des connaissances (1996-2007), Gallia, 2009:

- ^ Ferdière 2009, p. 187: L'évolution du site, des origines au Moyen ge

- ^ a b Ferdière 2009, p. 175: Javols/Anderitum et les Gabales

- ^ Ferdière 2009, p. 172: Javols/Anderitum et les Gabales

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 173–174: Javols/Anderitum et les Gabales

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 173–175: Javols/Anderitum et les Gabales

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 188–189: Une dimension environnementale

- ^ a b c Ferdière 2009, p. 182: L'évolution du site, des origines au Moyen ge

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 182–184: L'évolution du site, des origines au Moyen ge

- ^ Ferdière 2009, p. 184: L'évolution du site, des origines au Moyen ge

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 185–186: L'évolution du site, des origines au Moyen ge

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 186–187: L'évolution du site, des origines au Moyen ge

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 187–188: L'évolution du site, des origines au Moyen ge

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 175–176: Historique des recherches

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 176–177: Historique des recherches

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 189–193: Urbanisme et voirie à Anderitum

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 194–196: Urbanisme et voirie à Anderitum

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 198–199: Monuments et équipements publics

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 200–201: Monuments et équipements publics

- ^ Ferdière 2009, p. 179: Javols/Anderitum: une ville capitale de la civitas Gabalorum »

- ^ a b Ferdière 2009, p. 201: Monuments et équipements publics

- ^ a b Ferdière 2009, p. 204: Habitats privés et vie quotidienne

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 204–205: Habitats privés et vie quotidienne

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 209–210: L'espace des morts à Anderitum

- ^ Ferdière 2009, pp. 212–213: L'économie de la ville: productions et échanges

- Javols-Anderitum (Lozère), chef-lieu de la cité des Gabales: une ville romaine de moyenne montagne - bilan de 13 ans d'évaluation et de recherche, Monique Mergoil, 2011:

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 16: Javols-Anderitum dans l'Histoire

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 141: L'évolution du Triboulin

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 154: L'environnement du site de Javols

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 46: La Préhistoire et la Protohistoire ancienne

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 47: Le site à l'époque gauloise

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 34: Occupation du sol et paysage rural autour de Javols

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 49–51: Une fondation urbaine augustéenne?

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 53–54: Évolution de la ville au Haut-Empire

- ^ a b Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 54–55: Évolution de la ville au Haut-Empire

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 63: Javols du Moyen ge central aux Temps Modernes (xe-xixe siècle)

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 55: Évolution de la ville au Haut-Empire

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 58: Le déclin du Bas-Empire (fin iiie-ve siècle)

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 147–150: La romanisation

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 152: Une capitale éphémère

- ^ a b Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 22–24: Des conditions spécifiques de fouilles

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 42: Les limites du site

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 74: Plan général d'urbanisme et voies internes

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 77: Monuments et équipements publics

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 82–83: Monuments et équipements publics

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 53: Évolution de la ville au Haut-Empire

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 86: Monuments et équipements publics

- ^ a b Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 87: Monuments et équipements publics

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 96: La gestion de l'eau

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 98: La gestion de l'eau

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 86–87: Monuments et équipements publics

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 88–90: Les équipements cultuels et funéraires

- ^ a b Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 134–135: Production et approvisionnement de la ville

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 90: Les équipements cultuels et funéraires

- ^ a b Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 38–39: Activités péri-urbaines

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 135: Production et approvisionnement de la ville

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 136–137: Production et approvisionnement de la ville

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 76: Monuments et équipements publics

- ^ a b Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 139: Production et approvisionnement de la ville

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 138: Production et approvisionnement de la ville

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, p. 116: Habitat domestique et construction

- ^ Trintignac, Marot & Ferdière 2011, pp. 139–140: Production et approvisionnement de la ville

- Carte archéologique de la Gaule - La Lozère. 48, Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres-MSH, 2012:

- ^ Ferdière 2012, pp. 218–223

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 278

- ^ Ferdière 2012, pp. 285–286

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 226

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 227

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 287

- ^ a b Ferdière 2012, p. 283

- ^ Ferdière 2012, pp. 272–277

- ^ a b Ferdière 2012, p. 239

- ^ a b Ferdière 2012, p. 246

- ^ a b Ferdière 2012, p. 249

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 251

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 254

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 277

- ^ Ferdière 2012, pp. 272–275

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 260

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 274

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 266

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 270

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 280

- ^ Ferdière 2012, p. 281

- Les agglomérations «secondaires» dans le Massif Central (cités des arvernes, vellaves, gabales, rutènes, cadurques et lémovices), University of Clermont, 2015:

- ^ a b Baret 2015, pp. 114–115: Les agglomérations antiques dans le Massif central

- ^ Baret 2015, p. 161: Sources antiques et données archéologiques

- ^ Baret 2015, p. 310: Synthèse : de l'agglomération à la cité

- ^ Baret 2015, p. 118: Les agglomérations antiques dans le Massif central

- ^ Baret 2015, p. 304: Analyse par descripteur

- Other references:

- ^ "Notice n° PA00103827". Open heritage platform, Base Mérimée, Ministry of Culture (in French). Archived from the original on May 27, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise :Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Paris: Éditions Errance. pp. 45–46. ISBN 2-87772-237-6.

- ^ Lambert, Pierre-Yves (1994). La langue gauloise. Les Hespérides (in French). Éditions Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-089-2.

- ^ de Beaurepaire, François (1979). Les noms des communes et des anciennes paroisses de la Seine-Maritime (in French). Éditions Picard.

- ^ Duby 1980, p. 110

- ^ Reference and photograph under CIL XIII, 08883 Archived 2024-06-05 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2024-06-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Walckenaer, Charles-Athanase (1821). "Mémoire sur l'étendue et les limites du territoire des Gabali et sur la position de leur capitale Anderitum". Histoire et mémoires de l'Institut royal de France (in French). V: 386–418. doi:10.3406/minf.1821.1190.

- ^ "Congrès archéologique de France :XXIVe session :séances tenues à Mende, à Valence et à Grenoble (1857)". Société française d'archéologie (in French). 24: 103. 1858. Archived from the original on August 21, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Bideau, Caroline; Darnas, Isabelle; Trintignac, Alain (2008). La cité est dans le pré ; Javols, capitale antique du Gévaudan :Catalogue d'exposition (Banassac, Javols, Lanuéjols et Mende, juillet-septembre 2008 (in French). Conseil général de la Lozère. p. 18.

- ^ "Borne milliaire de Javols". L'Arbre celtique (in French). Archived from the original on January 2, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Pierobon-Benoit, Febbraro & Barbarino 1994, p. 233

- ^ Guibert, Pierre (2006). "Datation par thermoluminescence d'une structure de combustion granitique à Javols (Lozère) :Quelques considérations sur la microdosimétrie des irradiations naturelles". ArchéoSciences (in French). XXX: 127.

- ^ Arcelin, Patrice (1993). "Céramique non tournée protohistorique de Provence occidentale" (PDF). Lattara (in French) (6): 311. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-27. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ Coulon, Gérard (2006). Les Gallo-Romains. Civilisations et cultures (in French). Paris: Errance. p. 4. ISBN 2-87772-331-3.

- ^ Pierobon-Benoit, Febbraro & Barbarino 1994, p. 238

- ^ Charbonnel, Abbé (1865). Mende, premier siège des évêques du Gévaudan (in French). Vol. XVI. Bulletin de la Société d'agriculture, industrie, sciences et arts du département de la Lozère. p. 182. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Marot, Emmanuel (2007). "Une resserre incendiée au début du iie siècle apr. J.-C. à Javols-Anderitum (Lozère)". Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise (in French). XL: 326. doi:10.3406/ran.2007.1184.

- ^ Ferdière & Ode 2004, p. 215

- ^ Ode 2004, pp. 431–432

- ^ Ferdière & Ode 2004, pp. 215–216

- ^ "Structure politique et société de l'Antiquité gallo-romaine". l'Inrap (in French). January 17, 2016. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Delbecq, Denis (February 8, 2016). "Un âge glaciaire durant l'Antiquité". Le Temps (in French). Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ L'Ouvreleul, Jean-Baptiste (1724–1726). Mémoire historique sur le pays de Gévaudan et la ville de Mende (in French). Mende. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Piganiol de La Force, Jean-Aimar (1753). Nouvelle description de la France [...] (in French). Vol. VI. Legras. p. 414.

- ^ a b "Javols, capitale antique du Gévaudan" (PDF). Javols archaeological museum site (in French). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ "Seconde Guerre mondiale : la Résistance à Mende". Archives Municipales de Mende (in French): 17–18. 2011. Archived from the original on January 2, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Fouille de Javols-Anderitum (Lozère, Languedoc-Roussillon)". Citeres site (in French). Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ "Javols, capitale gabale". Departmental Council of Lozère site (in French). Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Nouvelle découverte archéologique à Javols". Midi Libre (in French). April 20, 2013. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ "Javols : les 50 ans de la découverte de la statue de Sylvain Sucellus". Departmental Council of Lozère site (in French). Archived from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Soto, Inès (April 29, 2019). "Lozère : des lunettes de réalité augmentée pour voir avec des yeux d'archéologues". Midi Libre (in French). Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ "Restitution 3D du site de Javols/Anderitum". CITERES site (in French). Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Pierobon-Benoit, Febbraro & Barbarino 1994, p. 237

- ^ Bedon, Robert (2001). La Loire et les fleuves de la Gaule romaine et des régions voisines (in French). Presses universitaires de Limoges. p. 87. ISBN 978-2-84287-177-2. Archived from the original on June 5, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Pierobon-Benoit, Rafaella (2004). "Javols, Anderitum – Las Pessos, parcelle A1111". Archéologie de la France - Informations (in French). doi:10.4000/adlfi.11821. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Béal, Jean-Claude; Peyre, Pierre (1987). "Une statue antique de Silvain-Sucellus à Javols (Lozère)". Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise (in French). XX: 353. doi:10.3406/ran.1987.1313.

- ^ Pailler, Jean-Marie (1989). "À propos du dieu de Javols". Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise (in French). XXII: 395–402. doi:10.3406/ran.1989.1352.

- ^ Talvas, Sandrine (2013). "Notes sur des figurines en terre cuite, témoins d'un culte domestique à Javols/Anderitum". Pallas (in French) (90): 177–184. doi:10.4000/pallas.665.

- ^ Rabeisen, Élisabeth; Saint-Didier, Guillaume; Gratuze, Bernard (2010). "L'artisanat des alliages cuivreux à l'époque romaine : témoignages d'une production métallurgique à Javols-Anderitum (Lozère)". Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise (in French). XLIII: 339–368. doi:10.3406/ran.2010.1813.

- ^ Pierobon-Benoit, Febbraro & Barbarino 1994, p. 254

- ^ "Site archéologique de Javols". patrimoines.laregion.fr (in French). Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ "Le musée archéologique de Javols". April 17, 2024 (in French). Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ "Le projet de valorisation du site archéologique". April 17, 2024 (in French). Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ "Le site archéologique de Javols en fleurs" (in French). August 23, 2021. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ "Des travaux d'entretiens et d'aménagements du site". April 17, 2024 (in French). Archived from the original on April 17, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "CITÉ ANTIQUE : JAVOLS 360, Un projet innovant et collaboratif". Patrimoines.laregion.fr. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ "Restitution 3D du site de Javols-Anderitum". May 7, 2024 (in French). Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ "AGP lance une application de visite VR pour le site Javols – Anderitum". Sitem.fr (in French). November 30, 2017. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ "Région Occitanie : « Le projet réalité virtuelle Javols est déjà un succès tant dans sa méthodologie collaborative que dans les productions". Club-innovation-culture.fr (in French). November 9, 2017. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ "Javols, comme si vous y étiez ! Voyagez 2 000 ans en arrière !". Lozere.fr (in French). Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "Salon International du Patrimoine Culturel, du 02 au 05 novembre 2017 au Carrousel du Louvre, en partenariat avec le CLIC France". Club-innovation-culture.fr (in French). November 2, 2017. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

Bibliography[edit]

Publications on Anderitum/Javols[edit]

- Ferdière, Alain; Ode, Benoît (2004). "Genèse, transformation et effacement de Javols-Anderitum". Revue archéologique du Centre de la France. « Capitales éphémères. Des Capitales de cités perdent leur statut dans l’Antiquité tardive, Actes du colloque Tours 6-8 mars 2003 » (in French) (25): 207–217. Archived from the original on May 27, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- Ferdière, Alain (2009). "Une petite ville romaine de moyenne montagne, Javols/Anderitum (Lozère), chef-lieu de cité des Gabales : état des connaissances (1996-2007)" (PDF). Gallia. Archéologie de la France antique (in French). LXVI (2): 171–225. doi:10.3406/galia.2009.3370.

- Ode, Benoît (2004). "Javols/Anderitum". Revue archéologique du Centre de la France. Capitales éphémères. Des Capitales de cités perdent leur statut dans l’Antiquité tardive, Actes du colloque Tours 6-8 mars 2003 (in French) (25): 431–434. Archived from the original on May 27, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- Peyre, Pierre (1982). "Les fouilles de Javols". La Revue du Gévaudan, des Causses et des Cévennes (in French) (4): 23–39.

- Pierobon-Benoit, Rafaella; Febbraro, Stefania; Barbarino, Paoloa (1994). "Anderitum (Javols, Lozère) 1989-1993 - Notes préliminaires sur la céramique". Actes du Congrès de Millau, 12-15 mai 1994 : Les sigillées du sud de la Gaule, Actualité des recherches céramiques (PDF) (in French). SFECAG. pp. 233–254.

- Trintignac, Alain; Marot, Emmanuel; Ferdière, Alain (June 2011). avols-Anderitum (Lozère), chef-lieu de la cité des Gabales : une ville romaine de moyenne montagne : bilan de 13 ans d'évaluation et de recherche. Archéologie de l'histoire romaine (in French). Vol. 21. Montagnac: Monique Mergoil. ISBN 978-2-35518-018-7.

Publications on regional or national archaeology and history[edit]

- Baret, Florian (2015). Les agglomérations « secondaires » dans le Massif Central (cités des arvernes, vellaves, gabales, rutènes, cadurques et lémovices) : ier siècle av. J.-C. : ve siècle apr. J.-C (PhD thesis) (in French). University of Clermont.

- Duby, Georges (1980). Histoire de la France urbaine, vol. 1 : La ville antique, des origines au 9e siècle. L’univers historique (in French). Paris: Le Seuil. ISBN 2-02-005590-2.

- Fabrié, Dominique (1989). Carte archéologique de la Gaule : La Lozère (in French). Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. pp. 33–43. ISBN 2-87754-007-3.

- Ferdière, Alain (2012). "Javols". Carte archéologique de la Gaule - La Lozère (in French). Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Maison des Sciences de l'Homme. pp. 216–288.

External links[edit]

- Architectural resource: Mérimée

- "Le Musée archéologique de Javols" (in French).