Andrew Kelsey

Andrew Kelsey | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1819 |

| Died | 1849 |

Andrew Kelsey, or Andy Kelsey, was an early American pioneer of California with his brothers Samuel and Benjamin Kelsey. Originally from Kentucky, he arrived in Alta California with the Bartleson–Bidwell Party in 1841, ventured into Oregon with his brothers, and participated in the Bear Flag Revolt. He eventually settled in the Clear Lake area in modern-day Lake County, California after acquiring livestock from Californio Salvador Vallejo. He and his business partner Charles Stone effectively enslaved local Pomo and Wappo bands and, along with Benjamin Kelsey, subjected them to starvation, torture, rapes and murders. Andrew Kelsey and Charles Stone were killed in 1849 during an Indian uprising triggered by their mistreatment of the indigenous population. Kelsey's name is attached to the town of Kelseyville in Lake County.

Early life

[edit]Andrew Kelsey was born in Barren County, Kentucky around 1819, the son of David Kelsey and Susan Jane Cossart. His family moved to Missouri in the 1830s. The "Kelso" family were "the first settlers of the Hoffman Bend section" in St. Clair County, Missouri, "considered pretty shrewd" and "inclined to make the most of their opportunities". Legal troubles followed them, as they attempted to secure some of their neighbors' pre-emption claims, and had to vacate the area. Andrew Jr. (as he was known then, his uncle being Andrew Sr.), his brother Samuel and their father David ended embattled in lawsuits. The same Missouri historian speculates that Jesse Applegate, a well-known St. Clair County figure, encouraged the Kelsos to explore new horizons.[1] (Samuel Kelsey married a Lucy Applegate, but relation is unknown.)

Along with his father and his brothers Samuel and Isaiah, Andrew appears in the 1840 U.S. Census in Deerfield, Missouri, where he is enumerated as a farmer and head of a family with two girls aged between 5 and 9.[2][3]

California trail

[edit]Andrew, his brother Benjamin and his wife Nancy arrived in Alta California in the Bartleson–Bidwell Party in November 1841.[4] The other Kelsey brothers, Isaiah and Samuel, chose to head for Oregon with their father when the party reached Soda Springs. Ben and Andrew spent time at Sutter's Fort and trapping north of the San Francisco Bay before deciding to drive cattle to Oregon and meet up with their other brothers.[5]

In 1844, along with his brothers Ben and Sam and his father David, Andrew Kelsey was part of a party leading emigrants from Oregon on the Siskiyou Trail to Sutter's Fort.[6] Among the party were Joseph Willard Buzzell, who had married Margaret, one of Ben's daughters (and with whom he would eventually raise two daughters at the Fort), as well as William and William Fowler Jr. (who had married Rebecca, one of Andrew's sister). Buzzell, who was close to John Sutter, is credited for convincing the Kelseys to return to California.[7]

Historian H.H. Bancroft suggests Andrew Kelsey might have been part of Micheltorena's 1844-1845 campaign in captain John Gantt's company.[8] The man participated with his brothers in the Bear Flag Revolt of 1846, which ended Mexican control of California and established the California Republic (Andrew's sister-in-law Nancy Kelsey is said to have sewn the first Bear Flag).[9]

Kelsey met Charles Stone, who took part in the second rescue relief group sent for the Donner Party in 1847. Charles Stone and another man were given $500 to rescue Tamsen Donner's three young daughters. They eventually abandoned them at Donner Lake to head back west to avoid harsh weather conditions, "their packs stuffed with booty".[8][10][11]

Clear Lake

[edit]Captain Salvador Vallejo was the brother of Californio general Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, and had been pacifying Rancho Lupyomi, the grant he had received from the Mexican government. Both Salvador and his brother were in 1844 each granted 16 square leagues, or about 112 square miles (290 km2). Vallejo had hoped to sell the Clear Lake area grant to former Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs, who had befriended his general brother.

Settlement

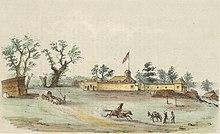

[edit]In 1847, Andrew and Ben Kelsey, Charles Stone, and E.D. Shirland acquired Salvador Vallejo's livestock near Clear Lake, composed of Texas longhorns and horses. It is unclear if they actually purchased grazing rights in Big Valley.[12] Andrew Kelsey and Charles Stone forced the local Indians to build them a two-room, 15 by 40 feet adobe home with a loft above, about 3 miles from the south shore of the lake, and immediately west of Kelsey Creek, as well as a large cattle corral. The construction took two months and several hundred laborers, who were fed with just one steer per day. Tensions rose further between the settlers and the Indians over Vallejo's remaining cattle, which he had allegedly left to the indigenous tribe, as Kelsey and Stone ordered the vaqueros to round it up. The Indians, belonging to different tribes, Lil'eek Wappo and Eastern Pomo, were forced to live in two enclosed camps they couldn't leave, on each side of the creek.[13] They were provided "very short rations", and were prohibited from fishing or hunting on the ranch – Stone and Kelsey had collected their weapons and stored them in the adobe house's loft.[14]

"Abuses included murder, starvation, slavery and rape", historian Henry Mauldin writes. Both men forcibly took indigenous women to live with them, one of them being the wife of a young man who would eventually become Pomo chief Augustine.[15][5] According to the Indian leader, Stone and Kelsey were known to take Indians "in the lower valleys and sold them like cattle or other stock",[14] capitalizing on the de facto slavery system institutionalized by Californio settlers and perpetrated by some California white pioneers.[12] Napa Valley pioneer George C. Yount is quoted mentioning Stone and Kelsey's "unbridled lusts among the youthful females", ordering fathers to bring them their daughters under the threat of corporal punishment.[13]

During the spring of 1848, resentment grew further and local tribe members besieged the adobe house where Stone and Kelsey had taken refuge. An Indian friendly to the Kelseys traveled to Buena Vista ranch in Sonoma to warn Benjamin Kelsey, who then assembled a party that included his other brother Samuel Kelsey, William M. Boggs (one of Lilburn Boggs's son), Richard A. Maupin, and Elias and John Graham. They traveled through Santa Rosa, met with Ems. Elliott who joined the party, then over Mount St. Helena and Cobb Mountain, following Kelsey Creek to reach the ranch after a day and half. The party then charged as loudly as possible toward the adobe house, dispersing the Indians and freeing Stone and Kelsey.[14] In the morning, the Kelseys and their party ordered a local chief to provide twelve dozen men to accompany the settlers to Scotts Valley, where they believed lived a tribe that had been "marauding the cattle". The next day, in the Blue Lakes area, the party captured a local Indian and ordered him to lead them to his tribe. Ben Kelsey, who suspected the man was leading them astray, ordered the Clear Lake Indians to each lash the captive. William Boggs later recollected the punishment and telling Richard Maupin "some white person would have to suffer for that whipping", foreboding Stone and Kelsey's deaths.[16] The rancherias of the Scotts Valley tribes were burned on the way back to the Kelsey ranch.

Augustine also mentions to Palmer that a hundred and seventy two men were taken to Sonoma to build adobe houses on Ben Kelsey's ranch, including himself. Augustine escaped, and the rest returned to Clear Lake in the fall.[14]

In the spring of 1849, during the California Gold Rush, Ben Kelsey took fifty men from Andrew's ranch to the Sierra foothills for a gold mining venture.[14] Left starving, dealing with malaria and surrounded by a hostile tribe, only one to three are thought to have survived.[17]

Death and aftermath

[edit]The motive for Stone and Kelsey's murders are debated. Pomo historian William Benson attributes the decision to kill the men primarily to the starvation the indigenous population endured.[13]

The circumstances around the deaths of Andrew Kelsey and Charles Stone vary depending on the accounts. Common themes involve the theft or sabotage of the men's guns by the indigenous women they were keeping, letting tribe members overrun the building and killing them the next morning. Kelsey would have been struck by an arrow – in some versions, he is killed instantly, in others it takes more blows to end his life. Stone also manages to flee but is soon killed, in a different area. Their bodies were later found in different locations.[14][13] The adobe building was pillaged for food, livestock was slaughtered to feed the population, and the rancherias were deserted.[13]

The uprising prompted the departure of other Anglo-American families from the area such as the Anderson and Beeson families, who left for Mendocino County (the Andersons would eventually give their name to Anderson Valley, where they settled).[18]

Several weeks passed until Ben Kelsey learned in December 1849 of the death of his brother. On Christmas Day, he informed First Dragoons lieutenant John Wynn Davidson in Sonoma he was heading to Clear Lake to avenge his brother, and assembled a posse of fifteen men. Davidson and a detachment guided by Kit Carson's brother arrived at the ranch the next day, killing Indians along the way.[12][5] Kelsey and Stone's bodies were recovered and were buried by the soldiers near the creek.[19] Davidson's men apprehended twelve "Isla Indians" found nearby to question them, but they were killed when they attempted to flee. The Dragoons followed the lake's shore to the north, and spotted a tribe on on an island, which he deemed too inaccessible for immediate retaliation. Lieutenant Davidson decided it would require another expedition.[5][12]

Ben Kelsey, furious sooner revenge couldn't be exacted, returned south and organized posses to terrorize indigenous populations in the Napa and Sonoma Valleys, killing individuals from different tribes and burning rancherias. The repression of the "Sonoma Raiders" triggered fear among local settlers and raised indignation in the press.[20][21] Kelsey and several of his men were arrested, but Ben and others made bail. The case would eventually be the first to reach the brand new California Supreme Court, but neither Kelsey or any of his men originally charged with murder and arson were ever tried.[5]

In early May 1850, an expedition was assembled to execute Davidson's retaliation plan against Clear Lake Indians: a company from the First Dragoons, a detachment from the 3rd Artillery and three detachments of the 2nd Infantry, equipped with at least one mountain howitzer, wagons and boats, commanded by brevet captain Nathaniel Lyon. On the 14th, they reached the western shore of Clear Lake and attacked a rancho. The next day, the military positioned itself on the north shore, and infantrymen crossed the waters to the island. Men, women and children were killed, or drowned in their attempt to escape the attack. The number of fatalities remain uncertain. Lyon claimed at least sixty and possibly over one hundred in his report. Other accounts place the indigenous deaths in the hundreds. Both Lyon and Davidson's detachments committed more mass murders in the days following the Bloody Island Massacre in search of Stone and Kelsey's attackers, notably in Cokadjal and Shanel.[12]

The adobe home was eventually torn down by new settlers for materials to build chimneys and other buildings.[22] Benjamin Kelsey sold the remaining Clear Lake cattle later in 1850 for "only $13,000", according to his wife.[23] E.D. Shirland, a Mexican-American War veteran who was partner with the Kelseys and Stone in the Clear Lake operation, and who had reportedly lived in the area for several months, served as an interpreter in August 1851 in the expedition Indian agent Redick McKee led to sign a treaty with the tribes of Clear Lake,[24][25] one of many the U.S. Army forced California tribes to sign to relinquish their rights in exchange for reservations.[26] Vallejo sold Rancho Lupyomi in 1852.[27]

Legacy

[edit]

Stone and Kelsey were judged harshly by some of their own contemporaries,[21][28] including John McKee, who acted as secretary for his father colonel Redick McKee during their Northern California expedition. "We have since learned that the death of the whites was caused by their own imprudence and cruelty to the Indians working for them, and that many innocent persons have suffered in consequence", McKee wrote on August 20, 1851.[29] Some 19th century historians echoed that sentiment, H.H. Bancroft writing that "Kelsey and Stone were both killed, as well they deserved to be",[30] and Lyman L. Palmer concluding that Stone and Kelsey "violated those grand fundamental principles which underlie all our relations with each other".[14]

The retaliations against Indian populations by Benjamin Kelsey, his brother Samuel and their men also raised outrage at the time.[31][32] The Bloody Island Massacre, which was led as a retaliatory action following the two men's murders, is considered a significant episode of the larger California genocide.

A second Kelsey family from Kentucky (some of which originally spelled their last name Kelsay) arrived in the area in 1861 with the Harriman Party.[33] Genealogical records seem to point to a common ancestor, John Kelsay/Kelso, born in Ireland in 1708. Accounts from their descendants, some of them collected by local historian Henry Mauldin, indicate however there was some uncertainty on the nature of the kinship.[34]

The settlement in Lake County was associated with Andrew and Ben Kelsey's name early on, the area being designated Kelsey Creek, Kelsey's Creek, Kelsey, then finally Kelseyville.[35][23] (Kelsey, an unincorporated community in El Dorado County, California originally known as Kelsey's Diggings, is named after Andrew's brother Ben.)[36] The Kelseyville name first appears in records in the 1860s,[37] the result of lobbying on the part of William and Barthena Kelsay, who arrived with the Harriman Party in Lake County in 1861, "in honor of their Kelsey cousins".[38] Voter registration records list the town as "Kelsey" in the 1860s, and the area is designated "Kelsey Creek" in the 1870 U.S. Census while voter records list "Kelseyville" in the same decade, that name also appearing in the 1880 U.S. Census. The name was officialized by federal authorities when the Uncle Sam Post Office was renamed to Kelseyville in October 1882.[39]

On May 5, 1950, the remains of Stone and Kelsey were exhumed from Piner Hill, to which they had been moved from their original location decades earlier by George Piner when he acquired the land.[19] Their bones were placed in a small wooden box, which was buried several days later beneath a newly erected monument marking the site of the former adobe house, one of five historical markers to be unveiled on Memorial Day by the Lake County Historical Society as part of California's statehood's centennial celebrations.[40][41] The marker is California Historical Landmark No. 426, sitting at the corner of Kelseyville's Main Street and Bell Hill Road.[42][43]

The town's name has been the source of controversy since at least the 1980s[44] because of its association with Andrew and Ben Kelsey. Several attempts have been made through petitions to suggest a name change.[45][46] In 2020, a group of local community members, Citizens for Healing, formed in order to change Kelseyville's name. The group originally planned a petition to put the issue on the ballot[45] (another petition was launched online in 2020[47]), until they were informed of another option. The group, after securing approval from local tribes,[48] filed a petition in October 2023 with the United States Board on Geographic Names (USBGN), requesting to rename the town "Konocti", after the mountain dominating the town's landscape.[49][50] The initiative has triggered opposition from another group, which has been campaigning under the "Save Kelseyville" slogan, arguing that renaming the town could be costly and cause confusion.[49] On July 30, 2024, the county's Board of Supervisors voted to approve a countywide "advisory measure" on the November 5 ballot to rename the town to "Konocti".[51][52][53] Measure U, which asked voters to recommend the name change to the Board, only received 29.4% of "Yes" votes.[54] On December 10, a majority of county Supervisors nevertheless voted in favor of recommending to the USBGN that the town be renamed Konocti.[55][56] The California Advisory Committee on Geographic Names is expected to provide a recommendation as part of the process.

Kelsey's name is also associated with Kelsey Creek, the stream going through Kelseyville which name also once designated the general area, as well as the Kelsey Bench-Lake County AVA, a wine appellation in Lake County, and Kelseyville Riviera, a subdivision southeast of Mount Konocti.

References

[edit]- ^ The History of Henry and St. Clair Counties, Missouri. National Historical Company. 1883. p. 833.

- ^ U.S. Census, United States census, 1840; Deer Field, Van Buren, Missouri; roll 232, page 126,, Family History film 0014858.

- ^ Benjamin Kelsey doesn't appear in that census, and it is possible that the two girls in question are some of Andrew's nieces.

- ^ "Old Settlers". Sacramento Transcript. Vol. 1, no. 22. 21 May 1850.

- ^ a b c d e Secrest, William B. "Chapter 2: Clear Lake". When the Great Spirit Died: The Destruction of the California Indians, 1850-1860. Word Dancer Press. pp. 23–35.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1886). "XIX - Immigration and Foreign Relations". History of California: 1840-1845. The History Company. p. 444.

- ^ "Stockton's oldest daughter". Vol. 6. The Berkeley Gazette. 29 December 1949. p. 1170.

- ^ a b Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1886). "California Pioneer Index and Register". History of California: 1840-1845. The History Company.

- ^ "Nancy Kelsey, a pioneer in her own backyard". The Lompoc Record. 5 January 2022. p. A8.

- ^ Mullen, Frank Jr. (1997), Donner Party Chronicles, Nevada Humanities Committee, p. 303

- ^ Acquaintances of the Kelseys like William Fowler had also participated in the Donner Party rescue, which might be how Andrew met Stone.

- ^ a b c d e Madley, Benjamin (2016). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe. Yale University Press. pp. 103–144.

- ^ a b c d e Radin, Max; Benson, William Ralganal (September 1932), "The Stone and Kelsey 'Massacre' on the shores of Clear Lake in 1849: The Indian viewpoint", California Historical Society Quarterly, 11 (3): 266–273, doi:10.2307/25178155, JSTOR 25178155

- ^ a b c d e f g Palmer, Lyman L. (1881). History of Napa and Lake Counties, California. Slocum, Bowen, & Co. Publishers.

- ^ "The Knave". Oakland Tribune. Vol. 165, no. 85. 23 September 1956. p. C1.

- ^ "New chapter in history of Clear Lake County". Petaluma Daily Morning Courier. Vol. 48, no. 53. 5 March 1910.

- ^ Fountain, Eugene F. (13 June 1957). "The Four Kelsey Brothers, Part I". Blue Lake Advocate. Vol. 69, no. 7.

- ^ "Pioneer corrects error". Cloverdale Reveille. Vol. 33, no. 4. 4 November 1911.

- ^ a b Mauldin Files, vol. 3, p. 710

- ^ "The Indian Outrages in Napa Valley". Daily Alta California. Vol. 1, no. 68. 19 March 1850.

- ^ a b "The Indians of Clear Lake". Daily Pacific News. Vol. 1, no. 158. 30 May 1850.

- ^ Mauldin Files, vol. 13, p. 2516

- ^ a b "Kelseys were pioneers for north section". The Press Democrat. Vol. XLIX, no. 70. 21 September 1921.

- ^ Index to Articles on Indian History and Culture, Minutes kept by Jon McKee, Secretary with the Expedition from Sonoma, throughout Northern California, 9 August 1851

- ^ "1851-1852 - Eighteen Unratifified Treaties between California Indians and the United States", California State University, Monterey Bay, Digital Commons @ CSUMB, p. 21

- ^ Shirland worked as clerk for the County of Sacramento, and later would fight as a Union captain in the American Civil War.

- ^ Mauldin Files, vol. 11, p. 2093

- ^ "The Kelseys and the Indians". Sacramento Transcript. Vol. 1, no. 117. 16 September 1850.

- ^ "Executive Document No. 4", Minutes kept by John McKee, Secretary, on the Expedition from Sonoma through Northern California, vol. Documents of the Senate of the United States during the Special Session called March 4, 1853, 1853, p. 142

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1883). "Pioneer Register and Index". History of California: 1841-1845. Vol. IV. The History Company. p. 698.

- ^ "Correspondence of the Alta California". Daily Alta California. Vol. 1, no. 61. 11 March 1850.

- ^ "The Recent Outrages upon the Indians". Daily Alta California. Vol. 1, no. 66. 16 March 1850.

- ^ "More Kelseys". Oakland Tribune. Vol. 165, no. 78. 16 September 1956. p. C1.

- ^ Pardee, Mike (5 September 1948). "Neighborly Kelseyville... Pear Capital". The Press Democrat. Vol. 92, no. 214.

- ^ "Death of Lake County Pioneer". Napa Weekly Journal. Vol. XXV, no. 51. 9 April 1909.

- ^ "The Knave". Oakland Tribune. Vol. 168, no. 12. 12 January 1958. p. C1.

- ^ "Feeling at Clear Lake". Sacramento Daily Union. Vol. 29, no. 4391. 18 April 1865.

- ^ Sylar, Ron M., Mauldin Files, vol. 44, p. 8302

- ^ "Postal Changes". Ukiah Dispatch Democrat. 13 October 1882.

- ^ Mauldin, Henry (5 May 1950), Mauldin Files, vol. 6, p. 1119

- ^ "Old Landmarks in Lake County To Be Honored". The Sacramento Bee. 29 May 1950.

- ^ "Site of First Adobe Home, Lake County Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org.

- ^ "Stone And Kelsey Home #426". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ^ "Town should change its name". Ukiah Daily Journal. 9 August 1989.

- ^ a b "Lake County group working to change the name of Kelseyville to redress violence against tribes". The Press Democrat. 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Kelseyville's name under scrutiny". Lake County Record-Bee. 20 September 2007.

- ^ "Petition to change the name of Kelseyville gains traction online". KZYX. 14 July 2020.

- ^ Murphy, Austin (15 August 2024). "'Friendly country town' of Kelseyville deeply divided over proposed name change". The Press Democrat.

- ^ a b Murphy, Austin (16 February 2024). "Kelseyville was named for a man who slaughtered Native Americans. Should a town still be named for him?". The Press Democrat.

- ^ "Quarterly Review List 454" (PDF), United States Board on Geographic Names, 23 January 2024

- ^ Larson, Elizabeth (31 July 2024). "Supervisors decide to put Kelseyville name change advisory measure before voters". Lake County News.

- ^ Beason, Tyrone (19 August 2024). "A town's name recalls the massacre of Indigenous people. Will changing it bring healing?". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Murphy, Austin (18 November 2024). "Lake County measure asking voters if Kelseyville's name should be changed is losing badly — but will it matter?". The Press Democrat.

- ^ "County of Lake, California: General Election Official Results". Lake County Registrar of Voters. 3 December 2024.

- ^ Chen, Lingzi (11 December 2024). "Lake County supervisors back Kelseyville name change despite voter opposition". Lake County News.

- ^ Murphy, Austin (12 December 2024). "Bucking will of Lake County voters, supervisors urge federal agency to change Kelseyville's name". The Press Democrat.

- 1819 births

- 1849 deaths

- American murder victims

- American people of the Bear Flag Revolt

- American slave owners in nominally free territories

- Bartleson–Bidwell Party

- Foreign residents of Mexican California

- History of Lake County, California

- People from Barren County, Kentucky

- People of the Conquest of California

- Perpetrators of the California genocide