Aretas IV Philopatris

Aretas IV Philopatris (Nabataean Aramaic: 𐢗𐢓𐢆 𐢊𐢛𐢞𐢞 𐢛𐢊𐢒 Ḥārītaṯ Rāḥem-ʿammeh "Aretas, friend of his people"[1]) was the King of the Nabataeans from roughly 9 BC to 40 AD.

His daughter Phasaelis [attribution needed] was married to, and divorced from, Herod Antipas. Herod then married his stepbrother's wife, Herodias. It was opposition to this marriage that led to the beheading of John the Baptist. After he received news of the divorce, Aretas invaded the territory of Herod Antipas and defeated his army.

Rise to power

[edit]

Aretas came to power after the assassination of Obodas III, who was apparently poisoned.[2] Josephus says that he was originally named Aeneas, but took "Aretas" as his throne name.[3] An inscription from Petra suggests that he may have been a member of the royal family, as a descendant of Malichus I.[4]

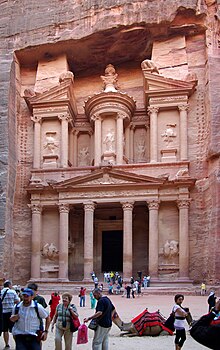

The capital of his kingdom was a prosperous trading city, Petra, some 170 miles south of Amman. Petra is famous for the many monuments carved into the rose-red sandstone. The power of the Nabateans extended over the caravan routes south and east of Judea, from the seventh century BC to the second century AD.[5]

His full title, as given in the inscriptions, was "Aretas, King of the Nabataeans, Friend of his People." Being the most powerful neighbour of Judea, he frequently took part in the state affairs of that country and was influential in shaping the destiny of its rulers. While not on particularly good terms with Rome, and though it was only after great hesitation that Augustus recognized him as king, he nevertheless took part in the expedition of Varus against the Jews in the year 4 BC, and placed a considerable army at the disposal of the Roman general.

Aretas had two wives. The first was Huldu to whom he was already married when he became king. Her profile was featured on Nabataean coins until 16 AD. After a gap of a few years the face of his second wife, Shaqilath, began appearing on the coins.[6]

Defeat of Herod Antipas

[edit]

Aretas' daughter, Phasaelis of Nabataea, married Herod Antipas, otherwise known as Herod the Tetrarch. Phasaelis fled to her father when she discovered her husband intended to divorce her in order to take a new wife, Herodias, mother of Salome. Herodias was already married to his brother, Herod II, who died around AD 33/34.[7] Antipas married Herodias. According to Christian accounts, it was opposition to this marriage that led to the beheading of John the Baptist.[8] However, the Jewish-Roman historian Josephus depicts John's execution instead as being a preemptive effort to prevent a rebellion.[9]

Aretas invaded Herod Antipas' domain and defeated his army, partly because soldiers from the region of Philip the Tetrarch (a third brother) gave assistance to King Aretas.[10] Josephus does not identify these auxiliary troops (he calls them 'fugitives'), but Moses of Chorene identifies them as being the army of King Abgarus of Edessa.[11] Antipas was able to escape only with the help of Roman forces.[12]

Herod Antipas then appealed to Emperor Tiberius, who dispatched the governor of Syria, Lucius Vitellius the Elder, to attack Aretas. Vitellius gathered his legions and moved southward, stopping in Jerusalem for the passover of AD 37, when news of the emperor's death arrived. The invasion of Nabataea was never completed.[13]

The Christian Apostle Paul mentions that he had to sneak out of Damascus in a basket through a window in the wall to escape the ethnarch of King Aretas (2 Corinthians 11:32, 33, cf Acts 9:23, 24). Proposals that control of Damascus was gained by King Aretas between the death of Herod Philip in 33/34 AD and his death in 40 AD are contradicted by substantial evidence against Aretas controlling the city before 37 AD and many reasons why it could not have been a gift from Caligula between 37 and 40 AD.[14][15] Most uncertainty stems from whether troops belonging to Aretas actually controlled the city, or if Paul was referring to "the official in control of a Nabataean community in Damascus, and not the city as a whole."[16][17][18] Several have proposed that Aretas briefly annexed Damascus after 37 AD.[19][20]

Aretas IV died in AD 40 and was succeeded by his son[citation needed] Malichus II and daughter Shaqilath II.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ G. W. Bowersock (1971). "A Report on Arabia Provincia". The Journal of Roman Studies. 61: 221. doi:10.2307/300018. JSTOR 300018.

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, 16.296 (16.9.4)

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, 16.294 (16.9.4)

- ^ Jane Taylor (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. I B Tauris. p. 66. ISBN 9781860645082.

- ^ Ronald Brownrigg (1971). Who's Who In The Old Testament, Volume 2. Wings Books. p. 34. ISBN 0-517-32170-X.

- ^ Jane Taylor (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. I B Tauris. p. 69. ISBN 9781860645082.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 18.4.6, 18.5.1, and 18.5.4

- ^ Ronald Brownrigg (1971). Who's Who In The Old Testament, Volume 2. Wings Books. p. 34. ISBN 0-517-32170-X.

- ^ Antiquities of the Jews (book 18, chapter 5, 2)

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, 18.109-118 or 18.5.1 Whiston references.

- ^ Moses of Chorene, History of Armenia, 2:2.29.

- ^ Ronald Brownrigg (1971). Who's Who In The Old Testament, Volume 2. Wings Books. p. 34. ISBN 0-517-32170-X.

- ^ Jane Taylor (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. I B Tauris. p. 72. ISBN 9781860645082.

- ^ Riesner, Rainer (1998) Paul's Early Period: Chronology, Mission Strategy, Theology Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing pg 73–89

- ^ Hengel, Martin (1997) Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: The Unknown Years Westminster John Knox Press pg 130

- ^ Alpass, Peter (2013) The Religious Life of Nabataea BRILL pg 175

- ^ Riesner, Rainer (1998) Paul's Early Period Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1998 pg 81-82

- ^ Gerd Ludemann (2002) Paul: The Founder of Christianity pg 38

- ^ John Barton and John Muddiman. The Oxford Bible Commentary: The Pauline Epistles. Oxford 2010, p 39

- ^ Douglas Campbell. "An Anchor for Pauline Chronology: Paul's Flight from "The Ethnarch of King Aretas" (2 Corinthians 11:32-33)". Journal of Biblical Literature 2002.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Aretas IV". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Aretas IV". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.