Arthur Lydiard

Arthur Lydiard | |

|---|---|

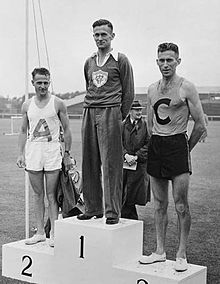

Lydiard (left) at the 1949 national marathon championships | |

| Born | Arthur Leslie Lydiard 6 July 1917 Auckland, New Zealand |

| Died | 11 December 2004 (aged 87) |

| Occupation(s) | Track and field coach |

| Spouse(s) | Jean Doreen Young (1940), Eira Marita Lehtonen (1977), Joelyne Van der Togt (1997) |

| Awards | |

Arthur Leslie Lydiard ONZ OBE (6 July 1917 – 11 December 2004) was a New Zealand runner and athletics coach. He has been lauded as one of the outstanding athletics coaches of all time and is credited with popularising the sport of running and making it commonplace across the sporting world. His training methods are based on a strong endurance base and periodisation.

Biography

[edit]Lydiard was born in Auckland, growing up in Sandringham. He attended Edendale School and Mount Albert Grammar School.[1] He spent much of his early life training to become a shoemaker. After noticing that his physical fitness was waning in his 20s, Lydiard set up the Owairaka Harriers, becoming the coach of the Owairaka Athletic Club.[2]

Lydiard competed in the Men's Marathon at the 1950 British Empire Games in Auckland, coming twelfth with a time of 2:54:51.[3]

Lydiard presided over New Zealand's golden era in world track and field during the 1960s sending Murray Halberg, Peter Snell and Barry Magee to the podium at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome. Under Lydiard's tutelage Snell went on to double-gold at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. Notable athletes subsequently coached by him or influenced by his coaching methods included Rod Dixon, John Walker, Dick Quax and Dick Tayler.

In the 1962 New Year Honours, Lydiard was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, for services to sport. On 6 February 1990, Lydiard was the 17th appointee to the Order of New Zealand,[4][5] New Zealand's highest civil honour. He also became a life member of Athletics New Zealand in 2003.

Arthur Lydiard died 11 December 2004 of a suspected heart attack in Texas, while on a lecture tour.

Training philosophy

[edit]Lydiard's ground-breaking impact on distance running was recognised by Runner's World, which hailed him as All time best running coach.

Lydiard constantly clashed with unimaginative and officious athletics administrators in his native New Zealand and in the countries that called upon his strong personality and coaching expertise to establish national athletics programmes.

The marathon-conditioning phase of Lydiard's system is known as base training, as it creates the foundation for all subsequent training. Lydiard's emphasis on an endurance base for his athletes, combined with his introduction of periodisation in the training of distance runners, were the decisive elements in the world-beating success of the athletes he coached or influenced. All of the training elements were already there in the training of Roger Bannister, the first miler who broke the 4-minute barrier for the mile, but Lydiard increased distance and intensity of training and directed the sport periodisation towards the Olympics and not the breaking of records.

Periodisation comprises emphasising different aspects of training in successive phases as an athlete approaches an intended target race. After the base training phase, Lydiard advocated four to six weeks of strength work. This included hill running and springing. This improved running economy under maximal anaerobic conditions without the strain on the achilles tendon, as it was still done in running shoes. Only after this spikes were put on and a maximum of four weeks of anaerobic training followed. (Lydiard found through physiological testing that four weeks was the maximum amount of anaerobic development needed—any more caused negative effects such a decrease in aerobic enzymes and increased mental stress, often referred to as burnout, due to lowered blood pH.) Then followed a co-ordination phase of six weeks in which anaerobic work and volume taper off and the athlete races each week, learning from each race to fine-tune himself or herself for the target race. For Lydiard's greatest athletes the target race was invariably an Olympic final.

Lydiard was renowned for his uncanny knack of ensuring that his athletes peaked for their most important races and, apart from his tremendous charisma and extraordinary ability to inspire and motivate athletes, this was largely a product of the periodisation principle he introduced into running training.

In the base training phase of his system Lydiard insisted, dogmatically, that his athletes—not least 800 metres athlete Peter Snell—must train 100 miles (160 km) a week. He was completely inflexible on this requirement. In the 1950s and 1960s, during the base phase of their training the athletes under Lydiard's tutelage would run a 35 km Sunday training route, starting from his famed 5 Wainwright Avenue address in Mt Roskill, through steep and winding roads in the Waitakere mountain ranges. The total cumulative ascent in the Waitakeres was over 500 metres. After laying such an arduous endurance base Lydiard's athletes—including Murray Halberg, Peter Snell, Barry Magee and John Davies—were ready to challenge the world, winning six Olympic medals amongst them in the 1960 Rome Olympics and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Snell, who after retiring from athletics in the mid-1960s went on to obtain a PhD in exercise physiology, stated in his autobiography No Bugles No Drums that the marathon-conditioning endurance aspect of Lydiard's training was the primary factor in his success as a world-beating middle-distance athlete.

The Lydiard system has been challenged since it was formalised and crystallised in the early 1960s. The two main sources of criticism of Lydiard emanate from the English coach, Frank Horwill, and the US coach, Jack Daniels. Horwill's Five Tier Training system departs from Lydiard in its claim that the maximum amount of weekly mileage that an athlete requires to achieve maximum aerobic efficiency is 110 km.

Horwill takes the view that Lydiard's insistence on 160 km a week in the base phase is at best superfluous, at worst an unnecessary cause of injuries and staleness. Horwill also differs from Lydiard in that he believes that all aspects of training must be present in a training programme at any time of the year and periodisation is a matter of simply emphasising one aspect of training such as speed or strength during a particular phase in which all the other training components are present.

Daniels, on the other hand, emphasises the need to train at what he terms threshold pace in order to achieve optimum athletic performance. He believes that the Lydiard system ignores training at such intermediate paces between the extremes of long, slow, distance running and fast, anaerobic, track work.

Legacy

[edit]Nearly every successful athletics coach or athlete active in the world today consciously or unconsciously emulates Lydiard's training system by laying an endurance base and making use of periodisation for peak performance. While the direct influence Lydiard exerted on the East African athletes is a matter for debate, what is indisputable is that the Kenyan and Ethiopian athletes do significant amounts of endurance work and make use of periodisation.

Efforts have been made across the world to preserve and promote the training and coaching legacy left by Lydiard. In his native New Zealand, the Legend marathon, which follows the famous training route followed by Lydiard's greatest athletes over the Waitekere Ranges west of Auckland, was established in his memory by Zimbabwean-born Ian Winson. In the United States, where Lydiard's ideas gained most currency worldwide, the Lydiard Foundation was established by two Lydiard disciples, Nobby Hashizume and New Zealand 1992 Olympic women's marathon bronze medalist Lorraine Moller, to promote Lydiard's training philosophy. In Johannesburg, South Africa, one of the few athletics clubs in the world to be named after a coach, the Lydiard Athletics Club, was founded in 2009 to promote Lydiard's training methodology and promote running as a way of life amongst youth.

As recently as 2009, Lydiard's training methods were also credited as the catalyst for the qualification of an unprecedented three South African male athletes, Juan Van Deventer, Pieter Van Der Westhuizen and Johan Cronje, for the 1500 metres for the 2009 Track and Field Championships in Berlin.[6]

Rangiora High School has a house named after Lydiard. Lydiard Place, in the Hamilton suburb of Chartwell, is also named in Lydiard's honour.[7]

Time in Finland

[edit]While the work he did in the late 1960s in Finland is generally acknowledged to have led to the renaissance in Finnish distance running in the 1970s (with Pekka Vasala winning gold in the 1500 metres at the 1972 Munich Olympics and Lasse Virén winning gold in both the 5000 metres and 10,000 metres at the 1972 Olympics and the 1976 Montreal Olympics), his coaching experiences in Mexico and Venezuela were less successful. Lydiard was forced to leave both countries because of what he perceived as a lack of support for his coaching efforts and the needs of athletes there.

In total, Arthur Lydiard's stay in Finland, following the Finnish Track & Field Association invitation, lasted only 19 months, but had long-lasting effects.

Before his arrival, interval training had been, unsuccessfully, the cornerstone of the Finnish training during the 1960s. Due to this background and the Finns' reluctance to change, his stay initially created mixed reviews.

However, most importantly, the new training methods were picked up by the trainers of Pekka Vasala, and Lasse Virén's coach Rolf Haikkola. Lydiard's advice is often seen as complementary to those given at the time by Percy Cerutty, an Australian coach, Paavo Nurmi, the Flying Finn, and Mihály Iglói, a Hungarian coach.

The first signs of positive results from Lydiard's visit came when Juha Väätäinen won the 5.000 and the 10.000 meters in the 1971 European Athletics Championships after blasting sprint finishes.

He was inducted into the Order of the White Rose of Finland for his efforts.

Jogging

[edit]Lydiard was a strong promoter of running for health, encouraging easy distance running for its cardiovascular health benefits at a time when people thought distance running was unhealthy and potentially dangerous. In 1961, with his group of followers, Lydiard organised the Auckland Jogging Club, a world first. During Bill Bowerman's New Zealand visit with his world class 4×1 mile team, Lydiard organised Bowerman to go on a jog with one of his members, three time heart attack-recovered Andy Steedman. Bowerman in his fifties struggled to keep up with a man twenty years his senior, and following his return to America took jogging to Hayward Field and eventually the masses.[8] Due in part to Bowerman's wide influence, Lydiard's competitive philosophies are sometimes conflated with jogging, including the myth of his promotion of long slow distance (LSD). However, in his updated training manual, "Running the Lydiard Way", Lydiard explained that, even on long runs, his top athletes moved at healthy paces to become "pleasantly tired."[9]

Books

[edit]- Lydiard, Arthur; Gilmour, Garth (1962). Run to the Top. London: H. Jenkins.

- Lydiard, Arthur; Gilmour, Garth (1978). Run, the Lydiard Way. Auckland: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. ISBN 0-340-22462-2.

- Lydiard, Arthur; Gilmour, Garth (1983). Jogging with Lydiard. Auckland: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. ISBN 0-340-32363-9.

- Lydiard, Arthur; Gilmour, Garth (1997). Running to the Top (2nd ed.). Germany: Meyer & Meyer Sport. ISBN 3-89124-440-1.

- Lydiard, Arthur; Gilmour, Garth (1999). Distance Training for Young Athletes. Germany: Meyer & Meyer Sport. ISBN 3-89124-533-5.

- Lydiard, Arthur; Gilmour, Garth (1999). Distance Training for Women Athletes. Oxford: Meyer & Meyer Sport. ISBN 1-84126-002-9.

- Lydiard, Arthur; Gilmour, Garth (2000). Distance Training for Masters. Oxford: Meyer & Meyer Sport. ISBN 1-84126-018-5.

- Lydiard, Arthur; Gilmour, Garth (2000). Running With Lydiard (2nd ed.). Meyer & Meyer Sport. ISBN 1-84126-026-6.

References

[edit]- ^ Dunsford, Deborah (2016). Mt Albert Then and Now: a History of Mt Albert, Morningside, Kingsland, St Lukes, Sandringham and Owairaka. Auckland: Mount Albert Historical Society. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-473-36016-0. OCLC 964695277. Wikidata Q117189974.

- ^ Reidy, Jade (2013). Not Just Passing Through: the Making of Mt Roskill (2nd ed.). Auckland: Puketāpapa Local Board. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-927216-97-2. OCLC 889931177. Wikidata Q116775081.

- ^ "Commonwealth Games Federation – Commonwealth Games – 1950". Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Honours and Awards" (15 February 1990) 23 New Zealand Gazette 445 at 446.

- ^ "No. 42554". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 29 December 1961. p. 2.

- ^ Simnikiwe Xabanisa, "Young Athletes set hot pace in 1500m – Revived Coaching Methods Rejuvenate Middle Distance Running" 'Sunday Times' Sport (Johannesburg), 28 June 2009, p.8. '

- ^ "Honouring sportspeople". Waikato Times. 2 November 2012. p. 9.

- ^ "Jogging for Everyone". Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Lydiard misconceptions explained Archived 10 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. hillrunner.com (1 August 2013)

Further reading

[edit]- Arnd Krüger (1997). The History of Middle and Long Distance Running in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century, pp. 117 – 124, in: Arnd Krüger & Angela Teja (eds.): La Comune Eredità dello Sport in Europa. Rome: Scuola dello Sport – CONI

- Arnd Krüger: Training Theory and Why Roger Bannister was the First Four Minute Miler, in: 'Sport in History' 26 (2006), 2, 305 – 324 (ISSN 1746-0271)

External links

[edit]- Old Official Site at the Wayback Machine (archived 1 February 2005)

- Lydiard Foundation (non-profit)

- Lydiard Foundation book on training

- Obituary at the NZ Herald

- Profile at NZEdge.com

- Athletics.org.nz hall of fame

- Lydiard links

- Lydiard Athletics Club (South Africa)

- Arthur Lydiard biography from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- On the Run at NZonScreen (documentary of the Lydiart method, with video extracts online)

- Arthur Lydiard at the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame

- Arthur Lydiard at the New Zealand Olympic Committee

- New Zealand male long-distance runners

- New Zealand athletics coaches

- Olympic coaches for New Zealand

- Olympic athletes for New Zealand

- Athletes (track and field) at the 1964 Summer Olympics

- 1917 births

- 2004 deaths

- Athletes (track and field) at the 1950 British Empire Games

- Commonwealth Games competitors for New Zealand

- New Zealand Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- Members of the Order of New Zealand

- People educated at Mount Albert Grammar School