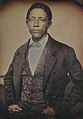

Augustus Washington

Augustus Washington | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1820 Trenton, New Jersey, United States |

| Died | June 7, 1875 (aged 55) Monrovia, Liberia |

| Nationality | American Liberian |

| Education | Oneida Institute Kimball Union Academy |

| Alma mater | Dartmouth College (no degree) |

| Occupation(s) | Daguerreotype photographer, politician |

| Notable work | Daguerreotype of John Brown |

| Speaker of the House of Representatives of Liberia | |

| In office 1865–1869 | |

| President | Daniel Bashiel Warner James Spriggs Payne |

| Preceded by | Henry Wesley Dennis |

| Succeeded by | William Spencer Anderson |

Augustus Washington (c. 1820 – June 7, 1875) was an American–Liberian photographer and politician. One of the few African American daguerreotypists whose careers have been documented,[1] Washington was born in New Jersey as a free person of color and in 1853 migrated to Liberia, where he later entered politics.

Early life

[edit]Augustus Washington was born in Trenton, New Jersey, as the son of a former slave and a woman who was said to be of South Asian descent. His mother died when he was a child.[2] He studied at Oneida Institute in Whitesboro, New York, and the Kimball Union Academy, before entering Dartmouth College in 1843. He learned how to make daguerreotypes during his first year to finance his college education, but had to leave Dartmouth in 1844 due to increasing debts. He moved to Hartford, Connecticut, teaching black students at a local school and opening a Daguerrean studio in 1846.[3]

Move to Liberia

[edit]Washington made the decision in 1852 to leave his home in Hartford to emigrate to Liberia in West Africa. It took him a year to raise the funds to travel, and he moved in 1853 with his wife, Cordelia, and their two small children. He wanted to move to Liberia to join thousands of other African Americans in leaving the United States to start a new free black nation in Africa where they would no longer be discriminated against and would enjoy equal rights.[4] The American Colonization Society started the process of moving African Americans to Liberia to help fund the colony. While Washington's intentions were to pave the way for a colony made by and for African Americans, the whole movement was still framed within a colonial context and Washington himself viewed the native Africans who were already living in Liberia as "heathen inhabitants" who would appreciate the African-American colonizers for bringing with them civilization and Western religion.[4]

Washington opened a daguerrean studio in the Liberian capital Monrovia in 1853[5] and also traveled to the neighboring countries Sierra Leone, Gambia and Senegal. His daguerreotypes came at a vital moment for the Liberian nation as they were a visible way to document the progress of the colony not only for the Liberians but also to create an image of the colony for Western audiences. Many of his daguerreotypes were even commissioned by the American Colonization Society to provide images that would be vital for presenting an idealized image of the nation to the men and women in the United States weighing the merits of recolonization in Africa.[4] Washington's Liberian portraits are of meticulously-posed elite members of the Liberian colony and focus on showing off the grooming, clothing, decoration and self-possession of his upper- and middle-class subjects.[4]

In addition to photographing members of the Liberian upper and middle classes, Washington also photographed many of Liberia's political leaders. These include likenesses of President Stephen Allen Benson, Vice President Beverly Page Yates, Senate chaplain Reverend Philip Coker, a number of senators, as well as the secretary, clerk, and sergeant-at-arms of the Senate.[4] The items placed in these portraits all held symbolic value for the representation of the Liberian politicians, from the papers found on desks in the foreground to the expensive material of the desks themselves. These were all meant to boost the public's view of the legitimacy of the new Liberian government.[4]

While his photography was extremely important to crafting an image of a new African colony, it was just that, an image. Instead of depicting the reality of the colony, Washington's portraits present and highlight an idealized vision of the colony, with highly constructed false representations.[4] As Shawn Michelle Smith points out in the journal article '"Augustus Washington Looks to Liberia", Washington's portraits "project a nation yet to come", and serve to double the vision of his work.[4]

Political career

[edit]After many years of producing such daguerreotypes, Washington began to realize the social hierarchies at play in Liberia and the length of their dependence on the African natives for everything from food to supplies. This disillusionment came as Washington noticed the distinct differences in which the African natives and the colonizers were treated by doctors and politicians. In Washington's view, the colonists were no longer bringing aid and enlightenment to the native Africans but were instead playing into a dangerous cycle of bigoted colonization through alienating the native other.[4]

Washington later gave up his photographic work and became a sugarcane grower on the shores of the Saint Paul River. In 1858 he began a political career, serving in both the House of Representatives and the Senate of Liberia. He served as Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1865 to 1869.[6] He died in Monrovia in 1875.[7]

Works

[edit]Washington is best known for a famous daguerreotype of John Brown.[8]

-

Portrait of Chancy Brown, sergeant-at-arms for the Senate of Liberia.

-

Portrait of Joseph Jenkins Roberts, the first and seventh president of Liberia.

-

Portrait of Urias McGill, a merchant in Monrovia, Liberia.

-

John Brown in 1846 or 1847.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "A Durable Memento". Smithsonian. May 1, 1999. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ "A Durable Memento".

- ^ The Connecticut Historical Society. "Augustus Washington: Hartford's Black Daguerreotypist". Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Michelle Smith, Shawn. "Augustus Washington Looks to Liberia". Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ Paoletti, Giulia. "Early Histories of Photography in West Africa (1860–1910)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Dunn, D. Elwood (May 4, 2011). The Annual Messages of the Presidents of Liberia 1848–2010: State of the Nation Addresses to the National Legislature. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783598441691 – via Google Books.

- ^ "A Durable Memento". National Portrait Gallery. Archived from the original on March 3, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego, At Freedom's Gate: Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs and the Story of Reconstruction Florida, B.A. Honors Thesis, (Hanover: Dartmouth College, 2007), 28–29; Augustus Washington, letter published in Charter Oak, Hartford Connecticut, 1846.

External links

[edit]- Exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery

- "African Colonization--By a Man of Color". Letter by Augustus Washington to The Tribune, July 3, 1851.

- U.S. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs division. Items by Augustus Washington