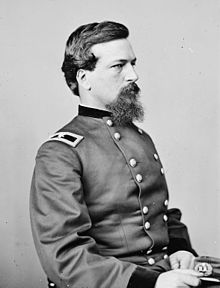

Alexander S. Webb

Alexander S. Webb | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd President of City College of New York | |

| In office 1869–1902 | |

| Preceded by | Horace Webster |

| Succeeded by | John Huston Finley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 15, 1835 New York City, New York |

| Died | February 12, 1911 (aged 75) Riverdale, Bronx, New York |

| Resting place | West Point Cemetery |

| Spouse |

Anna Elizabeth Remsen

(m. 1855) |

| Relations |

|

| Children | 8, including Alexander Stewart Webb Jr. |

| Parent | James Watson Webb (father) |

| Residence | Beechwood |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy |

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States (Union) |

| Branch/service | U.S. Army (Union Army) |

| Years of service | 1855–1870 |

| Rank | |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

Alexander Stewart Webb (February 15, 1835 – February 12, 1911)[1] was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War who received the Medal of Honor for gallantry at the Battle of Gettysburg. After the war, he was a prominent member of New York society and served as president of the City College of New York for thirty-three years.

Early life

[edit]Alexander Webb was born in New York City on February 15, 1835, to a prominent family with a strong military lineage. He was the son of Helen Lispenard (née Stewart) Webb and James Watson Webb, a former regular army officer who was a well-known newspaper owner and diplomat (serving as U.S. Minister to Brazil in 1861).[2] After his mother's death in 1848, his father remarried to Laura Virginia Cram, with whom he also had several children, including William Seward Webb, a doctor and financier who was married to Eliza Osgood Vanderbilt (granddaughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt), and Henry Walter Webb, a railroad executive.[3][4]

His paternal grandfather, Samuel Blatchley Webb, was wounded at the Battle of Bunker Hill and served on George Washington's staff during the American Revolutionary War,[2] and his paternal grandmother, Catherine Louisa (née Hogeboom) Webb, whose family was long associated with the Van Rensselaers of New York.[3] His maternal grandparents were Alexander L. Stewart and Sarah Amelia (née Lispenard) Stewart (the great-granddaughter of merchant Leonard Lispenard and a descendant of the Roosevelt family).[3][5]

Career

[edit]After preparing at Colonel Churchill's Military School in Sing Sing, New York (now Ossining, New York),[6] Webb entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, graduating in 1855, ranking 13 out of 34. He was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Artillery and was sent to Florida to serve in the Seminole War. After serving his duty in Florida, he was given an appointment to serve as an instructor of mathematics at West Point.[6]

Civil War

[edit]At the outbreak of the Civil War, Webb took part in the defense of Fort Pickens, Florida, was present at the First Battle of Bull Run, and was aide-de-camp to Brig. Gen. William F. Barry, the chief of artillery of the Army of the Potomac, from July 1861 to April 1862. During the Peninsula Campaign, he served as Gen. Barry's assistant inspector general and received recognition for his assembling an impregnable line of artillery defense during the Battle of Malvern Hill; Brig. Gen. Daniel Butterfield wrote that Webb saved the Union Army from destruction.[7]

During the Maryland Campaign and the Battle of Antietam, recently promoted to lieutenant colonel, he served as chief of staff in Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter's V Corps. After Antietam, he was ordered to Washington, D.C., where he served as Inspector of Artillery. In January 1863 he was again assigned to the V Corps, now commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, and served again as chief of staff. During the Battle of Chancellorsville, Meade gave Webb temporary command of Brig. Gen. Erastus B. Tyler's brigade and thrust him into battle. He performed well and Meade in his report on the battle paid particular detail to Webb's "intelligence and zeal". On July 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Webb brigadier general, to rank from June 23, 1863.[8][9] Three days before the Battle of Gettysburg, Brig. Gen. John Gibbon arrested the Philadelphia Brigade's commander, Brig. Gen. Joshua T. Owen, and Webb was given command of the brigade (the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, II Corps). Initially, the brigade resented having the meticulously groomed and well-dressed Webb as their commanding officer, but he soon earned their respect through his attention to detail, his affability, and his discipline.[6]

Gettysburg

[edit]

When the Union Army repulsed the Confederates at Cemetery Hill, General Webb played a central role in the battle. Coddington[10] wrote about Webb's conduct during Pickett's Charge: "Refusing to give up, [Webb] set an example of bravery and undaunted leadership for his men to follow...." Webb's brigade was posted on Cemetery Ridge with the rest of the II Corps on the morning of July 2, 1863. The brigade repulsed the assault of Brig. Gen. Ambrose R. Wright's brigade of Georgians as it topped the ridge late in the afternoon, chasing the Confederates back as far as the Emmitsburg Road, where they captured about 300 men and reclaimed a Union battery. Soon after, Webb sent two regiments to assist in counterattacking the assault of Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early's division on Cemetery Hill.[11]

On July 3, Webb's brigade happened to be in the center of the Union line to defend against Pickett's Charge, in front of the famous "Copse of Trees." As the Confederates launched a massive artillery barrage to prepare for their infantry assault, Webb made himself conspicuous to his men, many of whom were unfamiliar with their new commander. He stood in front of the line and leaned on his sword, puffing leisurely on a cigar while cannonballs whistled by and shells exploded all around. Although his men shouted at him to take shelter, he refused and impressed many with his personal bravery. As Maj. Gen. George Pickett's Virginia division approached to within a few yards, two companies of Webb's 71st Pennsylvania fell back, and Webb feared the personal disgrace and the results of a breakthrough in his line. He shouted to his neighboring 72nd Pennsylvania to charge, but they refused to budge. He attempted to grab their regimental colors and go forward with them himself, but apparently the standard bearer did not recognize him, because he fought Webb for the colors before he went down, shot numerous times. Webb ultimately gave up on the 72nd and strode directly in front of the chaos as Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead's Confederate brigade breached the low stone wall, over to his 69th Pennsylvania regiment. Webb was wounded in his thigh and groin by a bullet, but kept going. With the help of two of Col. Norman J. Hall's New York regiments, and Brig. Gen. William Harrow's men, who ran over in a mass to get in their shots, Webb and his men brought the Confederate assault to a standstill, inflicting heavy casualties.[11]

Webb received the Medal of Honor on September 28, 1891, for "distinguished personal gallantry in leading his men forward at a critical period in the contest" at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. President Lincoln nominated Webb for appointment to the brevet grade of major general of volunteers for his service at Gettysburg, to rank from August 1, 1864, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on February 14, 1865.[12]

Later in the war

[edit]After Gettysburg, Webb received command of the division six weeks later and led it through the fall campaigns. His division played a prominent role in the Battle of Bristoe Station. When Gibbon returned to command in the spring of 1864, Webb went back to brigade command for the Overland Campaign. At the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, in May, he was hit by a bullet that passed through the corner of his right eye and came out his ear, but did not impair his mental abilities. The wound resulted in a false report that he had been killed and his death was reported in the New York Times on May 9.[13]

He returned to the army on January 11, 1865, and was chief of staff of the Army of the Potomac from that date until June 28, 1865.[14] Webb was the assistant inspector general of the Military Division of the Atlantic between July 1, 1865, and February 21, 1866.[14] Webb was mustered out of the volunteer force on January 15, 1866.[14]

On April 10, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Webb for appointment to the brevet grade of brigadier general, USA (regular army), to rank from March 13, 1865, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on May 4, 1866.[15] On December 11, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Webb for appointment to the brevet grade of major general, USA (regular army), to rank from on March 13, 1865, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment February 23, 1867, recalled the confirmation on February 25, 1867, and reconfirmed it on March 2, 1867.[16]

Postbellum life

[edit]

General Webb stayed with the Army until 1870, assigned as a lieutenant colonel to the 44th U.S. Infantry Regiment, July 28, 1866, and the 5th U.S. Infantry Regiment, March 15, 1869.[14] He became unassigned, March 24, 1869.[14] During his final year, he served again as an instructor at West Point. He was discharged on December 5, 1870, with the final permanent rank of lieutenant colonel.[14]

From 1869 to 1902, General Webb served as the second president of the City College of New York, succeeding Horace Webster, also a West Point graduate.[1] The college's curriculum under Webster and Webb combined classical training in Latin and Greek with more practical subjects like chemistry, physics, and engineering.

General Webb was an early companion of the New York Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, being elected on March 18, 1866. He was a founder and first Commander General of the Military Order of Foreign Wars in 1894. He was also an honorary member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati.[6]

Personal life

[edit]On November 28, 1855, Webb was married to Anna Elizabeth Remsen (1837–1912), the daughter of Henry Rutgers Remsen and Elizabeth Waldron (née Phoenix) Remsen.[6] In February 1892, Webb, his wife, and their daughter and son, Caroline and Alexander, were all included in Ward McAllister's "Four Hundred".[17] Together, they were the parents of eight children, including:[18]

- Henry Remsen Webb (1857–1858), who died young.[6]

- Helen Lispenard Webb (1859–1929),[19] who married John Ernest Alexandre (1840–1910),[20] who was involved in steamships, in 1887.[21]

- Elizabeth Remsen Webb (1864–1926),[22] who married George Burrington Parsons (1863–1939),[23] the brother of William Barclay Parsons, in 1891.[24]

- Anne Remsen Webb (1866–1943), who did not marry and lived with her sister Caroline.[25]

- Caroline LeRoy Webb (1868–1950), who did not marry.[26]

- Alexander Stewart Webb Jr. (1870–1948),[27][28] who married Florence (née Sands) Russell (1871–1941),[29] the widow of architect William Hamilton Russell, in 1916.[30][31]

- William Remsen Webb (1872–1899), who died unmarried.[32]

- Louise de Peyster Webb (1874–1910),[33] who married William John Wadsworth in 1904.[6][34][35]

Webb died in Riverdale, New York on February 12, 1911.[1] He is buried in West Point National Cemetery.[36] A statue of General Webb was dedicated in the Gettysburg National Military Park in 1915.[37]

Descendants

[edit]Through his daughter Helen, he was the grandfather of Marie "Civilise" Alexandre (1891–1967), who married U.S. Olympian Frederic Schenck (1886–1919) in 1917;[38] and Anna Remsen Alexandre (1895–1984).[26]

Legacy

[edit]Webb was an articulate and graphic author who wrote extensively about the Civil War, including his book published in 1881, The Peninsula: McClellan's Campaign of 1862. A full-length bronze statue of him stands at Gettysburg Battlefield, overlooking the approach of Pickett's Charge. A full-length statue of General Webb, in full military uniform, also stands in his honor on the campus of the City College of New York.[39]

Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, chief of artillery of the I Corps, a friend and social peer of Webb in New York City, wrote that he was one of the "most conscientious, hard working and fearless young officers that we have." Meade's aide Theodore Lyman considered him "jolly and pleasant," although he was put off by Webb's "way of suddenly laughing in a convulsive manner, by drawing in his breath, instead of letting it out—the way which goes to my bones." But Lyman regarded Webb as a "thorough soldier, wide-awake, quick, and attentive to detail," despite this annoying quirk.

In popular culture

[edit]Civil War historian Brian Pohanka had a brief, uncredited appearance as Webb in the 1993 film Gettysburg, about the battle.[40]

See also

[edit]- List of Medal of Honor recipients for the Battle of Gettysburg

- List of American Civil War Medal of Honor recipients: T–Z

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c "Gen. A. S. Webb Dies.; Officer Who Held the Bloody Angle at Gettysburg Succumbs to Old Age". The New York Times. February 13, 1911. p. 1. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Browning, Charles Henry (1891). Americans of Royal Descent: A Collection of Genealogies of American Families Whose Lineage is Traced to the Legitimate Issue of Kings. Porter & Costes. p. 403. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c Webb, James Watson (1882). Reminiscences of Gen'l Samuel B. Webb of the Revolutionary Army. Globe Stationery and Printing Company. p. 6. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol. XXIV. New York City: New York Genealogical and Biographical Society. 1893. p. 114. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ Whittelsey, Charles Barney (1902). The Roosevelt Genealogy, 1649-1902. Press of J.B. Burr & Company. p. 103. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reynolds, Cuyler (1914). Genealogical and Family History of Southern New York and the Hudson River Valley: A Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of a Commonwealth and the Building of a Nation. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. p. 1457. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ Sword, p. 2081.

- ^ Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3. p. 730

- ^ President Lincoln nominated Webb for appointment to the grade of brigadier general on December 31, 1863, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on August 1, 1864. Eicher, 2001, p. 730

- ^ Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg campaign; a study in command, Scribner's, 1984.

- ^ a b Tagg, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Eicher, 2001, p. 715

- ^ "Death of Gen. A. S. Webb". The New York Times. May 9, 1864. p. 4. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Eicher 2001, p. 558

- ^ Eicher, 2001, p. 738

- ^ Eicher, 2001, p. 709

- ^ McAllister, Ward (February 16, 1892). "The Only Four Hundred: Ward M'Allister Gives Out the Official List. Here are the Names, Don't You Know, on the Authority of Their Great Leader, You Under- stand, and Therefore Genuine, You See" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ Moffat, R. Burnham (1904). The Barclays of New York: Who They Are And Who They Are Not,--And Some Other Barclays. R. G. Cooke & Company. p. 182. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ "Mrs. J.E. Alexandre Dies of Pneumonia; Was Former Helen Lispenard Webb, Daughter of Civil War General--In Many Societies". The New York Times. April 22, 1929. p. 23. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ "John E. Alexandre Dead.; He Wanted His Daughter Married at His DeathbeduLicense Lacking". The New York Times. Lenox, Massachusetts. August 23, 1910. p. 9. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Webb--Alexandre". The New York Times. May 12, 1887. p. 8. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mrs. George D. Parsons". The New York Times. April 30, 1926. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ "George B. Parsons; Was President of the '82 Class at Columbia--Dies at 76". The New York Times. June 30, 1939. p. Q25. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ "Joined for Life.; the Wedding of Miss Webb and Mr. George B. Parsons". The New York Times. November 15, 1891. p. 9. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Miss Anne R. Webb, Once War Worker; Daughter of Gem A. S. Webb, Who Was the President of City College, 1869 to 1903". The New York Times. July 13, 1943. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ a b "Died. Webb--Caroline LeRoy". The New York Times. October 8, 1950. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ "Alexander Webb, Head of ASPCA, 77; Retired Financier, a Banking Executive Many Years, Dies -- Aided Humane Association". The New York Times. January 24, 1948. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ Sons of the American Revolution Empire State Society (1899). Register of the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. The Society. p. 335. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ "Mrs. Alexander S. Webb". The New York Times. September 11, 1941. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ "Mrs. F. S. Russell to Wed.; Engaged to Alexander S. Webb, President of Lincoln Trust Co". The New York Times. April 20, 1916. p. 13. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "A.S. Webb Marries Mrs. W. H. Russell; Bride's Son, a Harvard Student, Gives Her in Marriage at Her Home. Amid Palms and Roses; Relatives and Close Friends Only at Ceremony;-Bridegroom Is President of Lincoln Trust Company". The New York Times. May 11, 1916. p. 11. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ Antietam, New York (State) Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg, Chattanooga and (1916). In Memoriam, Alexander Stewart Webb: 1835-1911. J.B. Lyon Company, printers. p. 106. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Died. Wadsworth". The New York Times. May 5, 1910. p. 11. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ "A Day's Weddings. Wadsworth--Webb". The New York Times. October 26, 1904. p. 9. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Married. Wadsworth--Webb". Army-Navy-Air Force Register and Defense Times. 36: 123. 1904. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ "Gen. A. S. Webb's Funeral; Military Honors for Veteran Here and at West Point Burial". The New York Times. February 16, 1911. p. 11. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Webb Statue Unveiled". The New York Times. Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. October 13, 1915. p. 7. Retrieved June 1, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harvard Alumni Bulletin. Harvard Bulletin, Incorporated. 1918. p. 32. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ The statue is on the east side of Convent Avenue near both Shepherd Hall and the Administration Building.

- ^ "IMDB". IMDb. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

References

[edit]- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Sword, Wiley. "Alexander Stewart Webb." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

External links

[edit]- Alexander Stewart Webb papers (MS 684). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

- "Brig. Gen. Alexander S. Webb's Official Report of the Battle of Gettysburg". Archived from the original on September 25, 2010. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1889.

- 1835 births

- 1911 deaths

- Union army generals

- United States Army Medal of Honor recipients

- United States Military Academy alumni

- Presidents of City College of New York

- People of New York (state) in the American Civil War

- Philadelphia Brigade

- Burials at West Point Cemetery

- American Civil War recipients of the Medal of Honor

- People from Briarcliff Manor, New York