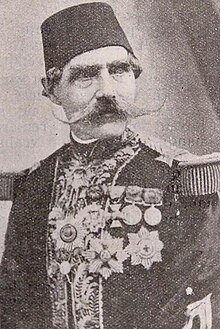

Charles de Schwartzenberg

Charles de Schwartzenberg-Schwartzburg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1809 Halle, Kingdom of Westphalia, First French Empire (modern-day Germany) |

| Died | December 1878 (aged 68 or 69) Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

| Spouse | Augustine de Norman d’Audenhove |

| Residences |

|

| Occupation | Aristocrat, soldier, statesman, memoirist |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service | Irregularly, between 1821 – 1878 |

| Battles/wars |

|

Charles de Schwartzenberg-Schwarzburg (1809 – December 1878), also known as General Baron de Schwartzenberg[2] and Emin Pasha (Ottoman Turkish: امين پاشا; Modern Turkish: Emin Paşa), was a French-born Belgian aristocrat, soldier, and statesman of German descent. Schwartzenberg was in the service of multiple armies of his age. He was most notably employed in the Ottoman army, which he was a part of for nearly 20 years (albeit irregularly), attaining the rank of Pasha by 1859. Schwartzenberg documented his experiences up to 1863 in his memoir, simply entitled Mémoires.[3]

Early life and career[edit]

Schwartzenberg was born into a poor family with an extensive military background in 1809 in French-ruled Halle, Kingdom of Westphalia. He claimed in his 8-page memorandum that his great-grandfather was a prince of the prestigious House of Schwarzenberg, as well as the House of Schwarzburg.[4] Although this assertion of his was neither confirmed or unverified, Schwartzenberg nonetheless enjoyed access to aristocratic circles.

He first entered military service aged 12 by enlisting into an infantry unit in Dutch-ruled Antwerp. After a brief break from the military, he fought against the Dutch in Ghent during the 1830 Belgian Revolution, and was recruited into the Belgian army as a lieutenant in 1835. In early 1840, Schwartzenberg unsuccessfully applied for a year's leave from the army with the intent of viewing developments on the battlefields of the 1839–1841 Egyptian–Ottoman War. Schwartzenberg's request for a break from the army was once again declined in 1841 when he hoped to observe French colonial forces subduing a rebellion in Algeria, under Ottoman control only 11 years prior. As a result of these successive failures, he requested to be honorably discharged. His request was granted in December of 1842.[5]

A few months later, he married a wealthy noblewoman by the name of Augustine, who was of French and Flemish descent. Augustine was the daughter of Count Auguste de Norman d’Audenhove, former chamberlain of the Austrian Emperor Francis I. The De Norman d'Audenhove family were a part of the Dutch and Belgian nobilities.[6]

After going bankrupt in 1846, he moved to Düsseldorf with his wife, attempting to join the Sardinian army in 1848, but to no avail. Shortly after, he joined the Hungarian army and fought in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 against Austrian forces as a lieutenant colonel in the 5th Hussar regiment. He worked closely with high-ranking generals such as Józef Bem, György Kmety, and Henryk Dembiński. They would all also enter into Ottoman service in the near future. Schwartzenberg was captured by Austrian soldiers in the Battle of Temesvár in August 1849, and was imprisoned for 14 months. He was released in October of 1850, and was treated well due to his noble status.[5]

Life in the Ottoman Empire[edit]

With the failure of the Hungarian Revolution, Schwartzenberg, alongside other Hungarian deserters, sought refuge in Bitola in the Sanjak of Monastir, Ottoman Empire.[7] He attempted to join the Ottoman army, but was declined on the basis of his religion. He once again tried to enlist in the Ottoman army in 1851 after traveling to Istanbul, albeit without success. A non-Muslim had to convert to Islam in order to serve in the army,[8] an action highly detested by Christendom[9] as it meant that the person would have 'turned Turk'.[10][11][12][13]

This requirement was lifted after the 1856 Reform Edict,[14] but Schwartzenberg was nevertheless given a post in the Ottoman army before this date. He was to serve as a colonel of a cavalry unit in Kars in the Crimean War from April 1854, arriving in the city by June,[15] and was a part of 23 foreign commanders who would aid in defending the city against the Russians.[16] Schwartzenberg climbed up the military ranks and became brigadier general in the summer of 1855,[17] having participated in multiple minor battles in Kars. He was present in the capitulation of the city in 29 November 1855, and was allowed to evacuate the city.

Soon after returning to Istanbul from Kars, Schwartzenberg was told in April 1856 that his Belgian citizenship had been revoked. Upon hearing this, he successfully applied for Ottoman citizenship, taking a break from the military and studying the Turkish language.[18] In 1859, he relocated to Damascus Eyalet to reinforce the Sublime Porte's control over Syria. He claimed in his memoir that bandits and tribes 'were the real masters of the country [Syria]'.[19] Schwartzenberg assumed control of the garrisons stationed at Homs, Maarat al-Numan, and Hama (which was to be his place of residence) with his relocation. As a Pasha of the Ottoman Empire, he also held power over the citizens of these cities. Schwartzenberg employed harsh measures against anyone who went against the orders of Sultan Abdulmejid I as well as his own, having led attacks on rebellious Bedouins in 1860, and burning a Druze village to the ground.[20]

Schwartzenberg admired and romanticised the strength and courage of Ottoman soldiers.[21] He held liberal reformers such as Mehmed Fuad Pasha and Izmet Pasha (governor of the Aleppo Eyalet) in high regard.[22] Although Schwartzenberg did not convert to Islam, which was unusual for European renegades in the Ottoman Empire, he did not think ill of the religion.[22]

Involvement in the Mount Lebanon crisis[edit]

Schwartzenberg played an active role in the 1860 civil conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus. In June 1860, he was ordered to strengthen the garrison of Damascus.[23] While traveling there, he was redirected to Baalbek to attend to the garrison of the city. Schwartzenberg claimed to have prevented a Druze massacre on the Christians of the city in 25 June. He was called to Damascus once again a week later, traveling to the city by 14 July with cannons and 300 soldiers. Schwartzenberg quickly restored order and brought the unrest to an end.[24]

He was praised by a multitude of European journals for the role he played in the crisis, with a French newspaper calling him a 'Christian belonging to a civilised nation' due to his efforts in safeguarding the Christians of Syria and Lebanon.[25] As a reward for his service, Schwartzenberg was given control of the garrison of Beirut in 1865.

Schwartzenberg was renowned for his loyalty to the Ottoman Empire and the Sultan, which is further seen in this statement from his memoir where he refers to a gift offered to him in a meeting with a leader of a Mawālī tribe:

"Achmed Bey, as a private individual, I would accept your gift, reserving my intention to make you another one in my turn; but... I am here as a representative of the Sultan, and I must act solely in his interest. This is what we call loyalty in Europe. In spite of the generous hospitality that I have just received under your tent, I do not yet know whether I should act towards you and your tribe as I act towards subdued subjects or if I must do it by forcing you, through [the use of] arms, to submit yourselves to the authority of the sovereign I serve. So... accepting your gifts with one hand and striking you with the other, would no longer be that loyalty I have just mentioned, and which... must be the principal armament of the character of an officer of my race."[26] [27]

Final years[edit]

Schwartzenberg ceased working on his memoir in 1863 for unknown reasons.[3] He relocated to Istanbul in 1866, living there with his spouse until 1868, which is when he decided to (temporarily) retire from the Ottoman military, citing a lack of promotion.[28] However, the actual reason is that he was forced to leave the Ottoman army as the government had lost confidence in his capabilities after he failed to subdue a revolt.

In January 1866, Schwartzenberg was ordered to march from Beirut to Ghazir to suppress the rebellion of Maronite Youssef Bey Karam. On 27 January, he negotiated with Karam in the village of Karmsaddeh, persuading him to surrender. However, Karam retracted his intent to surrender the next day, resulting in fatal clashes that caused the death of 60 to 200 Ottoman troops.[29]

This was a catastrophic event for Schwartzenberg as it portrayed both himself and the Ottomans as weak before the world, with one French newspaper describing the events by stating: 'Never was the Lebanon witness to a more complete disaster for the Crescent'.[30] Schwartzenberg was removed from his post and replaced with an Irish commander, Eugene O’Reilly, also known as Hassan Pasha.[31] O’Reilly was able to squash Karam's rebellion.[32]

Death[edit]

Schwartzenberg migrated in 1868 to Baden, Germany, with his wife. He often visited Brussels and led a reclusive life while in retirement. This reclusiveness, however, did not last long. After Serbia declared war on the Ottomans in 1876 (a precursor to the larger Russo-Turkish War), the now-widowed Schwartzenberg quickly met with the Ottoman ambassador to Germany, Ibrahim Edhem Pasha, telling him that he wanted to return to Ottoman military service. He volunteered as a cavalry commander in the Sanjak of Niş (modern Niš, Serbia) at age 67. It is not exactly known whether Schwartzenberg served till the end of the Russo-Turkish War.[33]

Schwartzenberg, aged 68 or 69, died in Istanbul in December 1878. He had served in the Ottoman army for nearly twenty years in total.[33]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Le Franc tireur, 25 May 1913, p. 181.

- ^ Anckaer, Jan. Small power diplomacy and commerce: Belgium and the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Leopold I (1831-1865). p. 127.

- ^ a b Alloul 2022, pp. 94, 97.

- ^ Extrait d’un petit mémoire écrit pour mes parents et amis qui me demandait pourquoi j’avais quitté le service actif en Turquie en 1868.

- ^ a b Alloul 2022, p. 93.

- ^ Adel, Hoge Raad van (1989). De Nederlandse adel: besluiten en wapenbeschrijvingen [The Dutch nobility: decrees and descriptions of arms] (in Dutch). The Hague: SDU. p. 288. ISBN 9012062063.

- ^ Mémoires, p. 196–200.

- ^ Deringil 2012, p. 160.

- ^ Deringil 2012, pp. 156–159.

- ^ Nicolay, Nicolas de (1595). The Nauigations, Peregrinations and Voyages Made Into Turkie. Translated by Thomas Washington. London: Thomas Dawson. p. 8.

- ^ Vaughan, Dorothy M. (1954). Europe and the Turk: A Pattern of Alliances, 1350-1700. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 282.

- ^ Bennassar, Bartolomé; Bennassar, Lucile (17 August 2017). Les Chrétiens d'Allah [The Christians of Allah] (in French). France: Place des éditeurs. p. 258. ISBN 9782262071172.

- ^ Isom-Verhaaren, Christine (2004). "Shifting Identities: Foreign State Servants in France and the Ottoman Empire". Journal of Early Modern History. 8 (1–2). Leiden: Brill: 113.

- ^ Gülsoy, Ufuk (1999). "ISLAHAT FERMANI" [REFORM EDICT]. İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). TDV İslâm Araştırmaları Merkezi.

- ^ Mémoires, p. 217.

- ^ Badem, Canan (2010). The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856). Leiden: Brill. p. 148. ISBN 9789004190962. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1kf.

- ^ Mémoires, p. 263.

- ^ Mémoires, p. 267.

- ^ Mémoires, p. 268.

- ^ Mémoires, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Mémoires, p. 270.

- ^ a b Alloul 2022, p. 101.

- ^ Reilly, James A. (2002). A Small Town in Syria: Ottoman Hama in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Peter Lang. p. 131. ISBN 0820456063.

- ^ Farah, Caesar E. (2000). The Politics of Interventionism in Ottoman Lebanon, 1830-61. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 592. ISBN 1860640567.

- ^ L’Ami de la Religion, vol. 7, p. 57.

- ^ Alloul 2022, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Mémoires, p. 276.

- ^ Letter to Samih Pasha, February 1877.

- ^ Spagnolo, John P. (April 1971). "Mount Lebanon, France and Dâûd Pasha". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 2 (2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 152, 154.

- ^ Public Opinion: A Comprehensive Summary of the Press Throughout the World, vol. 9, p. 199.

- ^ Jalabert 1975, p. 152.

- ^ Jalabert 1975, p. 155.

- ^ a b Alloul 2022, p. 98.

References[edit]

- Alloul, Houssine (2022). "'Me among the Turks?': Western commanders in the Late Ottoman Army and their self-narratives". Foreign Fighters and Multinational Armies. Vol. 27. Taylor & Francis. pp. 94–116. doi:10.4324/9781003276982-8. ISBN 9781003276982.

- Charles de Schwartzenberg's memoirs.

- Deringil, Selim (2012). Conversion and Apostasy in the Late Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139510486.

- Jalabert, Henri (1975). Un Montagnard contre le pouvoir, Liban 1866 [A Montagnard against power, Lebanon 1866.] (in French). Beirut: Dar El-Machreq. ISBN 2721459600.