Traditional Chinese characters

| Traditional Chinese | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

| Published | |

| Direction |

|

| Official script | Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau |

| Languages | Chinese |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Oracle bone script

|

Sister systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hant (502), Han (Traditional variant) |

| Traditional Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 正體字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 正体字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Orthodox form characters | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 繁體字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 繁体字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Complex form characters | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

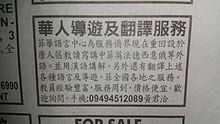

Traditional Chinese characters are a standard set of Chinese character forms used to write Chinese languages. In Taiwan, the set of traditional characters is regulated by the Ministry of Education and standardized in the Standard Form of National Characters. These forms were predominant in written Chinese until the middle of the 20th century,[1][2] when various countries that use Chinese characters began standardizing simplified sets of characters, often with characters that existed before as well-known variants of the predominant forms.[3][4]

Simplified characters as codified by the People's Republic of China are predominantly used in mainland China, Malaysia, and Singapore. "Traditional" as such is a retronym applied to non-simplified character sets in the wake of widespread use of simplified characters. Traditional characters are commonly used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, as well as in most overseas Chinese communities outside of Southeast Asia.[5] As for non-Chinese languages written using Chinese characters, Japanese kanji include many simplified characters known as shinjitai standardized after World War II, sometimes distinct from their simplified Chinese counterparts. Korean hanja, still used to a certain extent in South Korea, remain virtually identical to traditional characters, with variations between the two forms largely stylistic.

There has historically been a debate on traditional and simplified Chinese characters.[6][7] Because the simplifications are fairly systematic, it is possible to convert computer-encoded characters between the two sets, with the main issue being ambiguities in simplified representations resulting from the merging of previously distinct character forms. Many Chinese online newspapers allow users to switch between these character sets.[8]

Terminology

[edit]Traditional characters are known by different names throughout the Chinese-speaking world. The government of Taiwan officially refers to traditional Chinese characters as 正體字; 正体字; zhèngtǐzì; 'orthodox characters'.[9] This term is also used outside Taiwan to distinguish standard characters, including both simplified, and traditional, from other variants and idiomatic characters.[10] Users of traditional characters elsewhere, as well as those using simplified characters, call traditional characters 繁體字; 繁体字; fántǐzì; 'complex characters', 老字; lǎozì; 'old characters', or 全體字; 全体字; quántǐzì; 'full characters' to distinguish them from simplified characters.

Some argue that since traditional characters are often the original standard forms, they should not be called 'complex'. Conversely, there is a common objection to the description of traditional characters as 'standard', due to them not being used by a large population of Chinese speakers. Additionally, as the process of Chinese character creation often made many characters more elaborate over time, there is sometimes a hesitation to characterize them as 'traditional'.[11]

Some people refer to traditional characters as 'proper characters' (正字; zhèngzì or 正寫; zhèngxiě) and to simplified characters as 簡筆字; 简笔字; jiǎnbǐzì; 'simplified-stroke characters' or 減筆字; 减笔字; jiǎnbǐzì; 'reduced-stroke characters', as the words for simplified and reduced are homophonous in Standard Chinese, both pronounced as jiǎn.

Use by region

[edit]The modern shapes of traditional Chinese characters first appeared with the emergence of the clerical script during the Han dynasty c. 200 BCE, with the sets of forms and norms more or less stable since the Southern and Northern dynasties period c. the 5th century.

Hong Kong and Macau

[edit]This article needs attention from an expert in China. The specific problem is: The differences between traditional characters as used in Taiwan versus in Hong Kong. (September 2023) |

In Hong Kong and Macau, traditional characters were retained during the colonial period, while the mainland adopted simplified characters. Simplified characters are contemporaneously used to accommodate immigrants and tourists, often from the mainland.[12] The increasing use of simplified characters has led to concern among residents regarding protecting what they see as their local heritage.[13][14]

Taiwan

[edit]Taiwan has never adopted simplified characters. The use of simplified characters in government documents and educational settings is discouraged by the government of Taiwan.[15][16][17][18] Nevertheless, with sufficient context simplified characters are likely to be successfully read by those used to traditional characters, especially given some previous exposure. Many simplified characters were previously variants that had long been in some use, with systematic stroke simplifications used in folk handwriting since antiquity.[19][20]

Singapore

[edit]Traditional characters were recognized as the official script in Singapore until 1969, when the government officially adopted Simplified characters.[21] Traditional characters still are widely used in contexts such as in baby and corporation names, advertisements, decorations, official documents and in newspapers.[8]

Philippines

[edit]The Chinese Filipino community continues to be one of the most conservative in Southeast Asia regarding simplification.[citation needed] Although major public universities teach in simplified characters, many well-established Chinese schools still use traditional characters. Publications such as the Chinese Commercial News, World News, and United Daily News all use traditional characters, as do some Hong Kong–based magazines such as Yazhou Zhoukan. The Philippine Chinese Daily uses simplified characters. DVDs are usually subtitled using traditional characters, influenced by media from Taiwan as well as by the two countries sharing the same DVD region, 3.[citation needed]

North America

[edit]With most having immigrated to the United States during the second half of the 19th century, Chinese Americans have long used traditional characters. When not providing both, US public notices and signs in Chinese are generally written in traditional characters, more often than in simplified characters.[22]

Use on computers

[edit]Encoding

[edit]In the past, traditional Chinese was most often encoded on computers using the Big5 standard, which favored traditional characters. However, the ubiquitous Unicode standard gives equal weight to simplified and traditional Chinese characters, and has become by far the most popular encoding for Chinese-language text.

Input methods

[edit]There are various input method editors (IMEs) available for the input of Chinese characters. Many characters, often dialectical variants, are encoded in Unicode but cannot be inputted using certain IMEs, with one example being the Shanghainese-language character U+20C8E 𠲎 CJK UNIFIED IDEOGRAPH-20C8E—a composition of 伐 with the ⼝ 'MOUTH' radical—used instead of the Standard Chinese 嗎; 吗.[citation needed]

Typefaces

[edit]Typefaces often use the initialism TC to signify the use of traditional Chinese characters, as well as SC for simplified Chinese characters. In addition, the Noto, Italy family of typefaces, for example, also provides separate fonts for the traditional character set used in Taiwan (TC) and the set used in Hong Kong (HK).[23]

Webpages

[edit]Most Chinese-language webpages now use Unicode for their text. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) recommends the use of the language tag zh-Hant to specify webpage content written with traditional characters.[24]

Comparison with other scripts

[edit]In the Japanese writing system, kyujitai are traditional forms, which were simplified to create shinjitai for standardized Japanese use following World War II. Kyūjitai are mostly congruent with the traditional characters in Chinese, save for minor stylistic variation. Characters that are not included in the jōyō kanji list are generally recommended to be printed in their traditional forms, with a few exceptions. Additionally, there are kokuji, which are kanji wholly created in Japan, rather than originally being borrowed from China.

In the Korean writing system, hanja—replaced almost entirely by hangul in South Korea and totally replaced in North Korea—are mostly identical with their traditional counterparts, save minor stylistic variations. As with Japanese, there are autochthonous hanja, known as gukja.

Traditional Chinese characters are also used by non-Chinese ethnic groups. The Maniq people living in Thailand and Malaysia use Chinese characters to write the Kensiu language.[25][26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wei, Bi (2014). "The Origin and Evolvement of Chinese Characters" (PDF). Gdańskie Studia Azji Wschodniej. 5: 33–44. Retrieved 29 September 2023 – via CORE.

- ^ Kornicki, P. F. (2011). "A Transnational Approach to East Asian Book History". In Chakravorty, Swapan; Gupta, Abhijit (eds.). New Word Order: Transnational Themes in Book History. Worldview Publications. pp. 65–79. ISBN 978-81-920651-1-3.

- ^ Pae, H. K. (2020). "Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Writing Systems: All East-Asian but Different Scripts". Script Effects as the Hidden Drive of the Mind, Cognition, and Culture. Literacy Studies (Perspectives from Cognitive Neurosciences, Linguistics, Psychology and Education). Vol. 21. Cham: Springer. pp. 71–105. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-55152-0_5. ISBN 978-3-030-55151-3. S2CID 234940515.

- ^ Twine, Nanette (1991). Language and the Modern State: The Reform of Written Japanese. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-00990-4.

- ^ Yan, Pu; Yasseri, Taha (2016). "Two Diverging Roads: A Semantic Network Analysis of Chinese Social Connection ("Guanxi") on Twitter". Frontiers in Digital Humanities. 4. arXiv:1605.05139. doi:10.3389/fdigh.2017.00011.

- ^ O'Neill, Mark (8 June 2020). "China Should Restore Traditional Characters-Taiwan Scholar". EJ Insight. Hong Kong Economic Journal. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ Sui, Cindy (16 June 2011). "Taiwan Deletes Simplified Chinese from Official Sites". BBC. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ a b Lin Youshun (林友順) (2009). 大馬華社遊走於簡繁之間 [The Malaysian Chinese Community Wanders Between Simplified and Traditional Characters] (in Chinese). Yazhou Zhoukan. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ 查詢結果. Ministry of Justice (Republic of China). 26 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Academy of Social Sciences (1978). Modern Chinese Dictionary. Beijing: The Commercial Press.

- ^ Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 81.

- ^ Li Hanwen (李翰文) (24 February 2016). 分析:中國與香港之間的「繁簡矛盾」. BBC News (in Chinese). Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Lai, Ying-kit (17 July 2013). "Hong Kong Actor's Criticism of Simplified Chinese Character Use Stirs up Passions Online". Post Magazine. South China Morning Post. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ "Hong Kong TV Station Criticized for Using Simplified Chinese". SINA English. 1 March 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Chiang, Evelyn (11 April 2006). "Character Debate Ends up Being Nothing but Hot Air: Traditional Chinese Will Always Be Used in Education, Minister Says". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ "Taiwan Rules out Official Use of Simplified Chinese". Taiwan News. Central News Agency. 17 June 2011. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ 寫作測驗 [Writing Test]. Guozhong jiaoyu huikao (in Chinese).

若寫作測驗文章中出現簡體字,在評閱過程中可能被視為「錯別字」處理,但寫作測驗的評閱方式,並不會針對單一錯字扣分……然而,當簡體字影響閱讀理解時,文意的完整性亦可能受到影響,故考生應盡量避免書寫簡體字

- ^ 轉知:各校辦理課後社團,應檢視授課教師之教材內容,避免有不符我國國情或使用簡體字之情形. Xin beishi tong rong guomin xiaoxue (in Chinese).[permanent dead link]

- ^ Cheung, Yat-Shing (1992). "Language Variation, Culture, and Society". In Bolton, Kingsley (ed.). Sociolinguistics Today: International Perspectives. Routledge. pp. 211.

- ^ Price, Fiona Swee-Lin (2007). Success with Asian Names: A Practical Guide for Business and Everyday Life. Nicholas Brealey. ISBN 978-1-85788-378-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chia Shih Yar (谢世涯). 新加坡汉字规范的回顾与前瞻 [Review and Prospect of Standardization of Chinese Characters in Singapore]. Paper presented at The Fourth International Conference on Chinese Characters. Convened by The Society of Chinese Philology, Jiangsu Educational Publishing House and State Language Commission of PRC. Suzhou, China. 26–27 Nov 1997 (in Chinese) – via huayuqiao.org.

- ^ For instance, "22.31.1.6.3". Internal Revenue Manual. Internal Revenue Service. 6 November 2012.

The standard language for translation is Traditional Chinese

- ^ "Noto CJK". Google Noto Fonts.

- ^ "Internationalization Best Practices: Specifying Language in XHTML & HTML Content". W3C. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ Phaiboon, D. (2005). "Glossary of Aslian Languages: The Northern Aslian Languages of South Thailand" (PDF). Mon-Khmer Studies. 36: 207–224. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2024 – via Southeast Asian Linguistics Archives.

- ^ Bishop, N. (1996). "Who's Who in Kensiw? Terms of Reference and Address in Kensiw" (PDF). Mon-Khmer Studies. 26: 245–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2010 – via Southeast Asian Linguistics Archives.