Czesław Gawlikowski

Czesław Gawlikowski | |

|---|---|

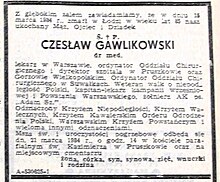

Czesław Gawlikowski in a military uniform with decorations, c. 1937 | |

| Born | February 25, 1899 |

| Died | March 15, 1984 (aged 85) |

| Other names | Adam S-II |

| Citizenship | Polish |

| Alma mater | University of Warsaw |

| Occupation(s) | doctor, military officer |

| Honours | Cross of Independence, Cross of Valour, Order of Polonia Restituta |

Czesław Gawlikowski (25 February 1899 – 15 March 1984) was a Polish military officer, doctor, and member of the resistance movement.[1]

Gawlikowski served as a corporal in the First Company of the Assault Battalion of the 5th Rifle Division during World War I. In the interwar period, he obtained his education in Warsaw (University of Warsaw) and then practiced medicine with a specialization in surgery in Warsaw and Przemyśl (he was a captain in the Polish Armed Forces and a physician from 1937 to 1939 at the 10th District Hospital). During World War II, he worked at the County Hospital in Pruszków (from 1 January 1940 to 30 June 1943), and after the defeat of the Warsaw Uprising, in which he participated, he worked at a hospital in Legionowo. In 1941, he joined the Home Army. From 1946 to 1953, he served as the director of the City Hospital in Gorzów Wielkopolski, and then as the head of the surgery department at the hospital in Suwałki until his retirement in 1977.

He received numerous military and civilian decorations, including the Cross of Independence, the Cross of Valour, and the Knight's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta.

Biography

[edit]Czesław Gawlikowski was the son of Wiktor and Kazimiera (née Szening). He was the eldest sibling of Witold, Wiktor, Zofia, Janusz, and Zbigniew. He grew up in Saint Petersburg in a family of Polish intellectuals (his father was a mathematician). The family originated from Wieliczka near Kraków.[1] From 1911 to 1918, he attended the V High School in Saint Petersburg, where he graduated with a high school diploma and a gold medal (valedictorian).[1]

World War I

[edit]On 25 June 1918, as a volunteer at the age of 19, he joined the Polish Legion in Omsk and entered the 5th Rifle Division (Siberia).[1] In September 1918, he completed a non-commissioned officer school in Ufa, and on 3 October 1918, he was promoted to corporal. He first served in the 9th Company of the 1st Polish Rifle Regiment named after Tadeusz Kościuszko, then in the 3rd Company of the 2nd Rifle Regiment, and from March 1919 in the Assault Battalion.[1]

He served there until the capitulation on 10 January 1920 at Klukwienna. He escaped on the same day and began collaborating with the Polish Secret Organization, which assisted Polish prisoners of war in Siberia and repatriated them to Poland.[2] In March 1920, he was arrested and imprisoned in Krasnoyarsk and Omsk, where he was interrogated by the Cheka. He was arrested while helping Jan Papis, a sergeant in the assault battalion, escape. After contracting typhus, he was transferred to a prison in Chelyabinsk, where he was forced to work alongside commanders Jan Medwadowski and Edward Dojan-Surówka.[2] He escaped on 5 July 1920 and hid under the name Józef Maliszewski in a mill near Chelyabinsk.[3]

He was at the mill when the Chekists arrived (after a tip-off in Chelyabinsk). A boy from a family ran to deliver the message that his father would be arrested and shot if the fugitive from the camp did not report to the mill. Czesław Gawlikowski ran to the mill to turn himself in. Nevertheless, the Chekists arrested not only him but also the miller. The miller confessed in Chelyabinsk that his name was not Maliszewski and that he had escaped from the camp out of hunger.[2] He was imprisoned and accused of being part of the Polish secret organization, escaping from the camp, and sentenced to death for these actions,[1] locked up in the worst conditions while waiting for the sentence to be approved by Kalinin. Fortunately, on 18 October 1920, a preliminary treaty (temporary ceasefire) was signed between Poland and Soviet Russia until a peace treaty was concluded in Riga (Latvia) on 18 March 1921.[1] This treaty provided for amnesty for prisoners sentenced to death. Czesław Gawlikowski escaped again and organized his own repatriation on foot to Moscow, where he was taken in by the Polish Red Cross and repatriated to Poland.[4]

From May to December 1921, he served in the 82nd Siberian Infantry Regiment in Brest-Litovsk.[3][5] After being transferred to the reserves and graduating from high school with a diploma in Polish, he began studying law at the University of Warsaw and later medicine.[1]

Interwar period

[edit]After four semesters of law studies, he transferred to medical studies in Warsaw. On 16 August 1928, he was called to active service in the Polish Armed Forces, and on 1 September 1928, he left for the Officers' Medical School in Warsaw. On 18 December 1928, he was promoted to head of all medical sciences and received the rank of second lieutenant.[6] In January 1929, he was transferred to the position of assistant doctor in the 60th Infantry Regiment in Greater Poland, and on January 1, he was assigned to the Józef Piłsudski First District Hospital in Warsaw. On 1 January 1931, having not received timely referral to a military hospital in a "specialty category", he requested to be released from active service while remaining in the reserves.[6]

From April 1929 to 1 June 1930, he worked as an assistant at the St. Zofia City Maternity Hospital in Warsaw, specializing in obstetric surgery.[7] From 1 February 1931, he worked at the Children's Hospital in Warsaw, first (until 30 October 1932) as a volunteer assistant, and then as an assistant to Dr. Zdzisław Sławiński[8] in the surgery department.[1][7]

From 1929, he lived in Pruszków. The mayor of Pruszków wrote about him as a very active social worker in the city:[7] he was the president of the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government, president of the Union of Former Volunteers of the Polish Army, and from 1934, a city councilor in Pruszków. In the local elections of 1934, he led the election campaign on behalf of the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government, and after the elections, he became a city councilor and the chairman of the Economic Unity Bloc. As a doctor, he volunteered with disabled children and mothers in facilities run by the Samaritan sisters.[7]

On 29 December 1936, he requested to be reinstated to active service, which he did on 4 May 1937, with the rank of captain,[9] with seniority from 1 January 1936. He was assigned to the hospital of the 10th District in Przemyśl, where he took the position of department head.[9][10]

World War II

[edit]

In September 1939, Czesław Gawlikowski was assigned to the Józef Piłsudski First District Hospital in Warsaw as a senior physician.[1] He was then evacuated with the hospital to Chełm Lubelski, where he briefly fell into Wehrmacht captivity. After his release, he returned to Pruszków.[1]

In 1941, he took an oath and joined the resistance, recruited by his friend Jan Papis, with whom he had maintained contact since the 1920s.[11]

The resistance unit was under the supervision of Hospital Director Czesław Gawlikowski, who ran surgery and obstetrics in the building at 4 Piękna Street. (...) "I returned to Pruszków from Volhynia at a time when the underground was already organized, both military and civilian. For a long time, I felt uneasy, noticing events and human behaviors that were not entirely clear to me. The hospital's quartermaster was an individual with the surname Papieski, which I considered to be an alias. Dr. Gawlikowski was close to Papieski, even friendly, but there was something in their relationship that suggested Papieski acted as if from a higher level than the director. He was often busy with hospital matters but frequently had unaccounted-for free days and longer absences, which were unclear to those not in the know. In the spring of 1943, Papieski was arrested by the Gestapo along with a group of people who attended a wedding ceremony at St. Alexander's Church in Warsaw. This event is widely known. Papieski managed to throw out a note, which was immediately delivered to the hospital and given to Director Gawlikowski. Only after the arrest did it become clear that Papieski, working under an alias, was deeply involved in underground activities. He was killed soon after his arrest. In fear of a search, everything that could arouse suspicion about other people had to be removed. Sister Gordon took care of this. Meanwhile, Director Gawlikowski left the hospital, relocating to an unknown area. He returned only after the war ended. As soon as he left, another surgeon, Colonel Michał Dobulewicz from the Łódź District Hospital, appeared at the hospital. The responsibility for the hospital fell on me. About two weeks later, County Physician Dorożyński arrived and informed me that the position of director had been entrusted to Dr. Dobulewicz, who, as a surgeon and military officer, was better suited to the role during wartime and occupation".[11]

In his hospital, Gawlikowski hid Jan Papis-Papiewski, who was then being sought by the Gestapo, employing him under a false name as an assistant.[12][13] He had to stop working because, in 1941, he was a member of the underground Home Army and was being hunted by the Gestapo after the arrest of the group he was part of, Osa–Kosa 30.[12] On 5 June 1943, he arrived very late for a wedding organized at St. Alexander's Church because he had been detained at his practice on Żelazna Street by a patient. As he walked towards the square, he saw Gestapo cars and immediately returned to his office. There, he received a phone call instructing him to hide immediately. Two days later, he continued his work, hiding under the alias Jan Zawada.[12]

He not only served as the group's doctor but also hid the plans for Operation Krüger in the hospital's boiler room.[14] He used the pseudonym Adam S-II[15][16] and was the deputy (right-hand man) of Dr. Józef Chojnowski (Adam I).[17] The S stood for the sanitary battalion. All hospital directors had trusted deputies who were familiar with medical records in case of arrest.[18]

He subsequently hid under a false identity in Henryków with the Sisters of the Good Samaritan – he was a long-time friend of Stanisława Umińska, Sister Benigna – at 257 Modlińska Street, referred to as Przystanek, until the Warsaw Uprising.[19][20] There, he continued his work as a doctor, hiding children from the ghetto brought in by Żegota, orphans from the bombed-out facility run by Father Boduena, entire families needing refuge, and soldiers from the internal military.[21]

The stable also housed a cache of weapons and a secret theater run by Leon Schiller.[22]

On 26 October 1942, Czesław Gawlikowski married Anna Cwiklińska in Zakopane, with whom he had two children: Andrzej Czesław and Elżbieta Anna. She joined him in Henryków shortly after the premature birth of their son Andrzej.[1][22]

Warsaw Uprising

[edit]Czesław Gawlikowski received an assignment to develop plans for medical support for the Warsaw Uprising for the VII District Brzozów/Legionowo.[23]

During the Warsaw Uprising, Corporal Ludwik Drzewiecki, codenamed Organ, went specifically to pick up Dr. Czesław Gawlikowski, Adam S-II, from the assembly point of the Sanitary Battalion. At the gathering point, two doctors, four nurses, eight medics, and a cleric reported.[17] Around midnight, the unit departed in a horse-drawn ambulance loaded with medical equipment, medicines, and first aid kits toward Jabłonna, where a field hospital for the battalion was to be established. The group was led by Organ along the route through Kępa Tarchomińska and further along the Vistula to the palace park in Jabłonna.[17] On August 2, around 5 AM, the group arrived at Jabłonna via Piaskowa Street, where instead of the planned observation posts, they encountered a German patrol. The group had not been informed that the previous day Jabłonna had been taken by a division of armored troops H. Goering, hastily brought in from Italy. The Germans, not receiving the correct password, opened fire. The medical unit managed to escape and hide, but one member, Jan Świątek, codenamed Piątek, was captured and executed on the spot by the Germans.[17]

From the following day, Czesław Gawlikowski worked in a partisan hospital in Legionowo, located in a villa on Krasińskiego Street, which was opened on 5 and 6 August 1944 due to the influx of many wounded.[24] To keep the Germans away from the facility, a sign was placed at the entrance reading: Infectious Hospital – Typhus. The hospital was organized by Dr. Władysław Binder and medic Kubica. Other doctors working there included Łukasz Bożęcki, Czesław Gawlikowski, Frydrychowicz, and Sturmer. Helena Polska served as the head nurse. The hospital also employed eight nurses, nuns, medics, and sanitary workers, with an average medical staff of about 22 people. The hospital had three wards with approximately 40 beds, an examination room, and an operating room. It was well-equipped thanks to a German medical train derailed by the partisans from the II Battalion near Chotomów.[17]

After the war

[edit]From November 1946 to 8 April 1954, he served as the director of the hospital in Gorzów Wielkopolski and chief of surgery. On 11 December 1951, he obtained a second-degree specialization in surgery.[25] Upon arriving in Gorzów, he discovered that the hospital had been completely plundered by the Red Army. The facility, which served the Lubusz Region and adjacent counties of the Szczecin Voivodeship, required serious repairs.[26] The destruction was not only structural but also included an almost complete lack of personnel, medications, and equipment. In defense of the hospital, Dr. Czesław Gawlikowski began a new battle against the aberrations of the new communist health care system.[26] His work was systematically sabotaged by the secretary of the Party Organization and the health department of the Voivodeship National Council, especially since his beliefs, which were not "politically correct" for those times, were well-known. Although Dr. Czesław Gawlikowski was deeply engaged in hospital matters, both in terms of improving infrastructure and staffing, his efforts could not succeed due to the political and economic situation. The city authorities were looking for a scapegoat to blame for the existing circumstances, and the director of the facility was a natural choice.[26] On 24 January 1953, a meeting of the Voivodeship National Council took place, where one of the topics was the assessment of the director's performance. The pretext for Czesław Gawlikowski's dismissal was his refusal to transfer rare and necessary medical equipment from the hospital to the hospital in Zielona Góra. Czesław Gawlikowski also worked voluntarily at the now-defunct House for Children and Mothers on Walczak Street.[26]

By the decision of the Minister of Health on 2 October 1954, he was transferred to Suwałki as the head of the surgery department at the Ludwik Rydygier Provincial Hospital.[7] For over 20 years, he advocated with the authorities in Białystok for funds to build a new hospital in Suwałki.[7]

In 1958, he became a member of the Provincial National Council in Białystok. He also served as the provincial inspector for medical adjudication and chair of the medical commission for pensions and disability benefits.[1] Almost until the end of his life, he worked to improve the health of the population. At the age of 82, he continued to receive loyal patients in his office located in a house on Kamedulska Street, where queues formed, especially on market days.[1]

He saved two children suffering from a severe form of diphtheria. In contact with a young patient, the doctor became infected, and the disease led to a serious heart defect that required lifelong care for the physician.[1] Czesław Gawlikowski passed away in Łódź, where he spent the last two years surrounded by family. He was buried in Pruszków next to his parents, sister Zofia, and brother Witold.[1]

Awards and honors

[edit]- Cross of Valour for the 1914–1921 war, record no. 55138, awarded after the war by the Ministry of Military Affairs.

- Cross of Independence – awarded for fighting for Poland's independence before the establishment of the Polish state.

- Commemorative Medal for the 1919–1921 War

- French 1914–1918 Inter-Allied Victory medal, record (journal) 60/25

- Badge of the Union of Former Volunteers of the Polish Army, record no. 512

- Badge of the 5th Rifle Division (Polish Army in the East)

- During the interwar period, he was awarded the Silver Cross of Merit for social work (as a city councilor in Pruszków).

- Knight's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta on the recommendation of the Minister of Health (1975).

- Medal of the 30th Anniversary of People's Poland – enacted by the Council of State.

- Gold Cross of Merit (1970).

- Badge for Exemplary Work in Health Service.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Ernst, Piotr (2015). "Dr Czesław Gawlikowski (1899–1984) – lekarz, oficer, społecznik" [Dr. Czesław Gawlikowski (1899–1984) – doctor, officer, social activist]. Acta Medicorum Polonorum (in Polish). 6 (2): 35–48. doi:10.20883/amp.2015/21. ISSN 2083-0343.

- ^ a b c Radziwiłłowicz, Dariusz, ed. (2013). Z ziemi rosyjskiej do Polski: Generał Jan A. Medwadowski w swoich wspomnieniach [From Russian Soil to Poland: General Jan A. Medwadowski in His Memoirs] (in Polish). Olsztyn: Instytut Historii i Stosunków Międzynarodowych Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurksiego w Olsztynie. p. 224. ISBN 978-83-935593-1-2.

- ^ a b Prugier-Ketling, Bronisław (1939). Księga chwały piechoty [Book of Glory of the Infantry] (in Polish). pp. 181–189.

- ^ Radziwiłłowicz, Dariusz (2009). Polskie formacje zbrojne we wschodniej Rosji oraz na Syberii i Dalekim Wschodzie w latach 1918-1920 [Polish Armed Formations in Eastern Russia and in Siberia and the Far East from 1918 to 1920] (in Polish). Olsztyn: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurskiego. ISBN 978-83-7299-594-0.

- ^ Rocznik oficerski 1923 [Officers' Yearbook 1923] (in Polish). Warsaw: Ministerstwo Spraw Wojskowych. 1923.

- ^ a b Rybka, Ryszard; Stepan, Kamil (1939). Awanse oficerskie w Wojsku Polskim 1935-1939 [Officer Promotions in the Polish Army 1935-1939] (in Polish).

- ^ a b c d e f Matusiewicz, Andrzej (2015). Szpital w Suwałkach: dzieje i ludzie: 1842-1895-2015 [Hospital in Suwałki: History and People: 1842-1895-2015] (in Polish). Suwałki: Szpital Wojewódzki im. dr. Ludwika Rydygiera. ISBN 978-83-941971-0-0.

- ^ Rudowski, W. (1 January 1968). "Zdzisław Sławiński, M.D., eminent Polish surgeon (1867–1936)". Archiwum Historii Medycyny. 31 (1): 1–20. ISSN 0004-0762. PMID 4882689.

- ^ a b Rybka, Ryszard; Stepan, Kamil (2006). Rocznik oficerski, 1939: stan na dzień 23 marca 1939 [Officers' Yearbook, 1939: As of March 23, 1939] (in Polish). Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka Fundacja Centrum Dokumentacji Czynu Niepodległościowego. pp. 383, 896. ISBN 978-83-7188-899-1.

- ^ "10 Szpital Okregowy. Kpt. dr Czeslaw Gawlikowsji" [10th Regional Hospital. Capt. Dr. Czesław Gawlikowski]. garnizon.projekt8813.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-10-14.

- ^ a b Steffen, Edward (1992). "Pamiętniki z czasów II wojny światowej: lata 1942-1945" [Memoirs from the Time of World War II: 1942-1945]. Przegląd Pruszkowski (in Polish). 1: 39.

- ^ a b c Biedrzycka, Agnieszka (2022). ""Notatki z wielkich czasów" i "Pamiętniki z lat 1916–1918". Ludomił German i jego zapiski z czasów I wojny światowej" ["Notes from the Great Times" and "Memoirs from the Years 1916–1918." Ludomił German and His Writings from the Time of World War I]. Polish Biographical Studies (in Polish). 10 (1): 181–210. doi:10.15804/pbs.2022.08.

- ^ "Oddziały Dyspozycyjne KG AK" [Disposal Units of the Command of the Home Army]. www.dws-xip.com (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-10-14.

- ^ Strzembosz, Tomasz (1983). Oddziały szturmowe konspiracyjnej Warszawy 1939-1944 [Assault Units of Underground Warsaw 1939-1944] (in Polish). Warsaw: Państ. Wydaw. Naukowe. pp. 58, 209, 212, 353, 404. ISBN 978-83-01-04203-5.

- ^ "Powstańcze Biogramy - Czesław Gawlikowski" [Insurgent Biographies - Czesław Gawlikowski]. www.1944.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-10-14.

- ^ "Czesław Gawlikowski". Encyklopedia Medyków Powstania Warszawskiego (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-10-14.

- ^ a b c d e Cudna-Kowalska, Pola, ed. (2004). Chotomów, Jabłonna w konspiracji i walce [Chotomów, Jabłonna in Conspiracy and Combat] (in Polish). Koło nr 11 Chotomów Światowego Związku Żołnierzy Armii Krajowej. pp. 68, 150.

- ^ Pawnik, Jolanta (12 March 2022). "Jak Izabela Wolfram została Bożymirem II, by organizować opiekę medyczną dla jeńców i uciekinierów z powstańczej Warszawy" [How Izabela Wolfram Became Bożymir II to Organize Medical Care for Prisoners and Refugees from Insurgent Warsaw]. HelloZdrowie (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-10-14.

- ^ Mieszkowska, Anna; Włodkowski, Bartłomiej (2015). Modlińska 257: miejsce magiczne [257 Modlińska Street: A Magical Place] (in Polish). Warsaw: Fundacja Ave. ISBN 978-83-937754-8-4.

- ^ Madeczyk, Czeslaw; Drozdowski, Marian Marek; Maniakowna, Maria; Stremborz, Tomasz; Bartoszewski, Władysław (1974). Ludność cywilna w powstaniu warszawskim [Civilian Population in the Warsaw Uprising] (in Polish). Vol. 1.

- ^ Puścikowska, Agata (2020). Siostry z powstania: nieznane historie kobiet walczących o Warszawę [Sisters of the Uprising: Unknown Stories of Women Fighting for Warsaw] (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak. ISBN 978-83-240-6089-4. OCLC 1183373434.

- ^ a b Umiński, Zdzisław (1984). Album z rewolwerem [Album with a Revolver] (in Polish) (1 ed.). Warsaw: Czytelnik. ISBN 978-83-07-00936-0.

- ^ Degiel, Rafał (2019). Powstanie warszawskie na terenie I Rejonu Legionowo [The Warsaw Uprising in the Area of I District Legionowo] (in Polish). Legionowo: Muzeum Historyczne. ISBN 978-83-944287-5-4.

- ^ "Szpitale polowe Rejonu "Brzozów" - Legionowo" [Field Hospitals of the "Brzozów" District - Legionowo]. www.szpitale1944.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2022-01-28.

- ^ Ernst, Piotr (2013). Funkcjonowanie ochrony zdrowia w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim w latach 1950-1956 [Functioning of Healthcare in Gorzów Wielkopolski in the Years 1950-1956] (Thesis) (in Polish). pp. 13, 67, 79, 80, 86, 87, 93, 103, 164.

- ^ a b c d "Trudne początki gorzowskiej służby zdrowia" [Difficult Beginnings of Healthcare in Gorzów]. ECHOGORZOWA.PL (in Polish). 9 March 2015. Retrieved 2024-10-14.