Dobrica Ćosić

Dobrica Ćosić | |

|---|---|

Добрица Ћосић | |

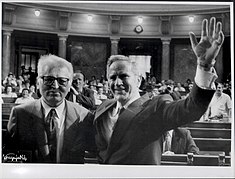

Ćosić in 1961 | |

| 1st President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia | |

| In office 15 June 1992 – 1 June 1994 | |

| Prime Minister | Aleksandar Mitrović (acting) Milan Panić Radoje Kontić |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Zoran Lilić |

| 15th Chairperson of the Non-Aligned Movement | |

| In office 15 June 1992 – 7 September 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Branko Kostić |

| Succeeded by | Suharto |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Dobrosav Ćosić 29 December 1921 Velika Drenova, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes |

| Died | 18 May 2014 (aged 92) Belgrade, Serbia |

| Resting place | Belgrade New Cemetery |

| Nationality | Serbian |

| Political party | SKJ (until 1968) |

| Awards | Order of Bravery Order of Merits for the People Order of Brotherhood and Unity NIN Award (1954, 1961) Pushkin Medal (2010) |

Dobrica Ćosić (Serbian: Добрица Ћосић, pronounced [dǒbritsa tɕôːsitɕ]; 29 December 1921 – 18 May 2014) was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician, writer, and political theorist.

Ćosić was twice awarded the prestigious NIN award for literature and Medal of Pushkin for his writing. His books have been translated into 30 languages.[1]

He was the first President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia with his tenure lasting from 1992 to 1994. Admirers sometimes refer to him as the Father of the Nation due to his influence on modern Serbian politics and the national revival movement in the late 1980s[2] while his opponents use that term in an ironic manner.[3]

Early life and career[edit]

Ćosić was born as Dobrosav Ćosić on 29 December 1921 in the Serbian village of Velika Drenova near Trstenik to parents father Žika and mother Milka (d. 15 October 1984).[2] Some sources have incorrectly stated his date of birth as 4 January 1922.[2]

Before the Second World War he was able to attend vocational agriculture school in Valjevo. He joined the communist youth organization in Negotin in 1939. When the Second World War reached Yugoslavia in 1941, he joined the communist Partisans.[4] After the liberation of Belgrade in October 1944, he remained active in communist leadership positions, including work in the Serbian republican Agitation and Propaganda commission and then as a people's representative from his home region. In the early 1950s, he visited the Goli otok political prison, where the Yugoslav authorities imprisoned political opponents of the Communist Party.[5] Ćosić maintained that he did so in order to better understand the Communist system.[6] Ćosić wrote his first novel Daleko je sunce (The Sun is Far Away) in 1951. The novel was a success and made him popular, launching him into a literary career where he could express his revolutionary ideals.[7] By that time, he had quit working professionally for the Communist Party.[7]

In 1956 he found himself in Budapest during the Hungarian revolt.[7] He arrived there for the meeting of the editors of literary magazines in socialist countries on the day when the revolution started and remained there until October 31 when he was transported back to Belgrade on a plane that brought in Yugoslav Red Cross help. It remains unclear whether this was purely a coincidence or he was sent there as a Yugoslav secret agent. Nevertheless, he even held political speeches in favor of a revolution in Budapest and upon his return he wrote a detailed report on the matter which, by some opinions, greatly affected and shaped firm official Yugoslav view on the whole situation. Parts of his memories and thoughts on the circumstances later will be published under the name Seven Days in Budapest.[8]

In late 1956 Ćosić was chosen to participate in the formation of a new program for the Communist Party. Tito and Edvard Kardelj both picked Ćosić to sit on the committee along with other prominent Yugoslav communists. When it was completed in 1958, Ćosić had claimed that he himself wrote parts of it, including the chapter on "Social-Economic System".[9] Ćosić was concerned about the program's neglect of culture and pressed for more attention to be given to the role of culture in socialism but Kardelj, who was the final arbiter, was unresponsive to these concerns.[9]

In opposition[edit]

Until the early 1960s, Ćosić was devoted to Marshal Tito and his vision of a harmonious Yugoslavia. In 1961, he joined Tito on a 72-day tour by presidential yacht (the Galeb) to visit eight African non-aligned countries.[10] The trip aboard the Galeb highlighted the close, affirmative relationship that Ćosić had with the administration until the early 1960s.

Between 1961 and 1962, Ćosić got involved in a lengthy polemic with the Slovenian intellectual Dušan Pirjevec regarding the relationship between autonomy, nationalism and centralism in Yugoslavia.[11] Pirjevec voiced the opinions of the Communist Party of Slovenia which supported a more decentralized development of Yugoslavia with respect for local autonomies, while Ćosić argued for a stronger role of the Federal authorities, warning against the rise of peripheral nationalisms. The polemic, which was the first public and open confrontation of different visions within the Yugoslav Communist Party after World War II, ended with Tito's support of Ćosić's arguments. Nevertheless, actual political measures undertaken after 1962 actually followed the positions voiced by Pirjevec and the Slovenian Communist leadership.[11] Precipitated by a slow economy, opposing sides came to use Ćosić and Pirjevec as proxies in their battles for a competing vision of Yugoslavia in the early to mid-1960s.[6]

As the government gradually decentralized administration of Yugoslavia after 1963, Ćosić grew convinced that the Serbian population of the state was imperiled. In May 1968, he gave a celebrated speech to the Fourteenth Plenum of the Central Committee of the Serbian League of Communists, in which he condemned the then-current nationalities policy in Yugoslavia. He was especially upset at the regime's inclination to grant greater autonomy to Kosovo and Vojvodina. Thereafter he acted as a dissident. In the 1980s, following the death of Tito, Ćosić helped organize and lead a movement whose original goal was to gain equality for Serbia in the Yugoslav federation, but which rapidly became intense and aggressive. He was especially enthusiastic in his advocacy of the rights of the Serb and Montenegrin populations of Kosovo.[11]

Ćosić was a member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, and is considered by many to have been its most influential member. While Ćosić has been credited with writing the Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, which appeared in unfinished fashion in the Serbian public in 1986, he in fact was not responsible for its writing. In 1989 he endorsed the leadership of Slobodan Milošević, and two years later he helped raise Radovan Karadžić to the leadership of the Bosnian Serbs.[12][13] When war broke out in 1991, he supported the Serbian effort.[11] In 1992, Ćosić wrote that Bosnia and Herzegovina was a "historical freak" and he considered that with the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the Serbs were forced to find a state-political form of resolving their national question and he supported the idea that all Serbian ethnic areas should become part of the federation of Serbian lands.[14]

President of FR Yugoslavia[edit]

In 1992, he became the president of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which consisted of Serbia and Montenegro. On Eastern Orthodox Christmas Eve of January 1993, Ćosić appeared on Serbian television to warn of demands for “national capitulation” from the West: "If we don't accept, we are going to be put in a concentration camp and face an attack by the most powerful armies of the world". These outside forces, he said, are determined to subordinate "the Serbian people to Muslim hegemony."[15] His support was important in the rise to power of Serbian nationalist leader Slobodan Milošević. Liberal Serbs saw Ćosić as one of the key people behind the Greater Serbia project, an idea pushed forward by Serbian nationalists who wanted to unite Serbia with Serb-populated areas of Croatia and Bosnia.[16] Later, Ćosić turned against Milošević, and was removed from his position for that reason.

In 2000, Ćosić publicly joined Otpor!, an underground anti-Milošević organization.[17]

Personal life[edit]

In 1947, he married his wife Božica (née Đulaković) (1929–2006), with whom he had a daughter named Dr Ana Ćosić Vukić.[18][19]

Ćosić and Chomsky[edit]

In 2006, Ćosić received support for his proposal for a partition of Kosovo by Noam Chomsky. In a Serbian television interview, Chomsky was asked what the best solution for Kosovo's final status is. He responded:

My feeling has been for a long time that the only realistic solution is one that in fact was offered by the President of Serbia [i.e. Dobrica Ćosić, then President of Yugoslavia] I think back round 1993, namely some kind of partition, with the Serbian, by now very few Serbs left but the, what were the Serbian areas being part of Serbia and the rest be what they called "independent" which means it'll join Albania. I just don't see…I didn't see any other feasible solution ten years ago.[20]

Death and legacy[edit]

Dobrica Ćosić died on 18 May 2014 in his home in Belgrade at the age of 92.[21] He was interred in a family plot at the Belgrade New Cemetery next to his wife on 20 May 2014.[22]

In March 2019, a street in Belgrade was named after him.[23]

Literary works[edit]

- Dаleko je sunce (1951)

- Koreni (1954)

- Deobe I-III (1961)

- Akcija (1964)

- Bаjkа (1965)

- Odgovornosti (1966)

- Moć i strepnje (1971)

- Vreme smrti I-IV (1972–1979)

- Stvarno i moguće (1982)

- Vreme zlа: Grešnik (1985)

- Vreme zlа: Otpаdnik (1986)

- Vreme zlа: Vernik (1990)

- Promene (1992)

- Vreme vlаsti 1 (1996)

- Piščevi zаpisi 1951—1968 (2000)

- Piščevi zаpisi 1969—1980 (2001)

- Piščevi zаpisi 1981—1991 (2002)

- Piščevi zаpisi 1992—1993 (2004)

- Srpsko pitаnje I (2002)

- Pisci mogа vekа (2002)

- Srpsko pitanje II (2003)

- Kosovo (2004)

- Prijаtelji (2005)

- Vreme vlаsti 2 (2007)

- Piščevi zаpisi 1993—1999 (2008)

- Piščevi zаpisi 1999—2000: Vreme zmijа (2009)

- Srpsko pitanje u XX veku (2009)

- U tuđem veku (2011)

- Bosanski rat (2012)

- Kosovo 1966-2013 (2013)

- U tuđem veku 2 (2015)

- Knjiga o Titu (2023)

On Ćosić[edit]

- Pesnik revolucije na predsedničkom brodu, (1986) - Dаnilo Kiš

- Čovek u svom vremenu: rаzgovori sa Dobricom Ćosićem, (1989) - Slаvoljub Đukić

- Authoritet bez vlаsti, (1993) - prof. dr Svetozаr Stojаnović

- Dobrica Ćosić ili predsednik bez vlаsti, (1993) - Drаgoslаv Rаnčić

- Štа je stvаrno rekаo Dobrica Ćosić, (1995) - Milan Nikolić

- Vreme piscа: životopis Dobrice Ćosićа, (2000) - Rаdovаn Popović

- Lovljenje vetrа, političkа ispovest Dobrice Ćosićа, (2001) - Slаvoljub Đukić

- Zаvičаj i Prerovo Dobrice Ćosićа, (2002) - Boško Ruđinčаnin

- Gang of four, (2005) - Zorаn Ćirić

- Knjigа o Ćosiću, (2005) - Drаgoljub Todorović

- Moj beogradski dnevnik: Susreti i razgovori s Dobricom Ćosićem, 2006–2011, (2013) - Darko Hudelist

References[edit]

- ^ "Dobrica Ćosić | Laguna". www.laguna.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ^ a b c Zorica Vulić (11 May 2000). "Ko je ovaj čovek?: Dobrica Ćosić" (in Serbian). Glas javnosti.

- ^ Lukić, Svetlana Lukić & Svetlana Vuković (16 March 2007). "Injekcija za Srbe". B92: Peščanik. Archived from the original on 2007-03-27.

- ^ Boško Novaković (1971). Živan Milisavac (ed.). Jugoslovenski književni leksikon [Yugoslav Literary Lexicon] (in Serbo-Croatian). Novi Sad (SAP Vojvodina, SR Serbia): Matica srpska. pp. 78–79.

- ^ West, Richard (2012). Tito and the Rise and Fall of Yugoslavia. Faber & Faber. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-57128-110-7.

- ^ a b Miller 2007, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Ognjenović & Jozelic 2016, p. 109.

- ^ Ognjenović & Jozelic 2016, p. 147.

- ^ a b Miller 2007, p. 87.

- ^ Miller 2007, p. 97.

- ^ a b c d Cohen, Lenard J. & Jasna Dragovic-Soso (1 October 2007). State Collapse in South-Eastern Europe: New Perspectives on Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557534606.

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of the 'Butcher of Bosnia' - Transitions Online". www.tol.org. 22 July 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "Karadzic: From Dissident Poet to Most Wanted". balkaninsight.com. Balkan Insight. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Safet Bandažović; (2019) Nedovršena prošlost u vrtlozima balkanizacije (in Bosnian) p. 53; Centar za istraživanje moderne i savremene historije, Tuzla [1]

- ^ "Serbia's Spite", Time, 25 January 1993.

- ^ "Dobrica Cosic dies at 92; author and Yugoslavian president". Los Angeles Times. May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ Istinomer.rs (2016-10-17). "I Dobrića Ćosić u Otporu" (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- ^ Politika (2015-12-31). "U radnoj sobi Dobrice Ćosića" (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- ^ "Dobričini koreni duboko u Drenovini". Novosti.rs, 25.5.2014.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (2006-04-25). "Noam Chomsky about Serbia, Kosovo, Yugoslavia and NATO War". YouTube (8 parts). Interviewed by Danilo Mandic. RTS Online. pt 8, 2 min, 25 sec. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- ^ B92 (2014-05-18). "Preminuo Dobrica Ćosić" (in Serbian). Retrieved 2018-05-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Telegraf (2014-05-20). "U SENCI POPLAVA: Sahranjen Dobrica Ćosić" (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- ^ Politika (2019-03-04). "Dobrića Ćosić i Milorad Ekmečić dobili ulice u Beogradu" (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-03-24.

Sources[edit]

- Miller, Nick (2007). The Nonconformists: Culture, Politics, and Nationalism in a Serbian Intellectual Circle, 1944-1991. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9776-13-5.

- Ognjenović, Gorana; Jozelic, Jasna (2016). Titoism, Self-Determination, Nationalism, Cultural Memory: Volume Two, Tito's Yugoslavia, Stories Untold. Springer. ISBN 978-1-13759-747-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Slavoljub Đukić (1989). Čovek u svom vremenu: razgovori sa Dobricom Čosićem. Filip Višnjić. ISBN 9788673630861.

- Jasna Dragović-Soso (2002). Saviours of the Nation?: Serbia's Intellectual Opposition and the Revival of Nationalism. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-457-5.

- Miller, Nicholas J. (1999). "The Nonconformists: Dobrica Ćosić and Micá Popović Envision Serbia". Slavic Review. 58 (3): 515–536. doi:10.2307/2697566. JSTOR 2697566. S2CID 161960476.

- 1921 births

- 2014 deaths

- People from Trstenik, Serbia

- Presidents of Serbia and Montenegro

- Serbian political philosophers

- Serbian politicians

- Serbian male writers

- Serbian male essayists

- Serbian novelists

- Serbian non-fiction writers

- Serbian atheists

- Serbian communists

- Yugoslav science fiction writers

- Yugoslav Partisans members

- Members of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Secretaries-General of the Non-Aligned Movement

- Burials at Belgrade New Cemetery

- 20th-century Serbian novelists

- 21st-century Serbian novelists

- 20th-century Serbian politicians

- 20th-century presidents in Europe