Domestic dependent nations

| Domestic dependent nations | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Category | Autonomous administrative divisions |

| Location | United States |

| Created |

|

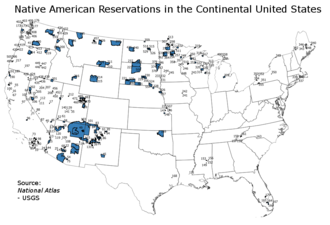

| Number | 326[1] (map includes the 310 as of May 1996) |

| Populations | 123 (several) – 173,667 (Navajo Nation)[2] |

| Areas | Ranging from the 1.32-acre (0.534 hectare) Pit River Tribe's cemetery in California to the 16 million–acre (64,750 square kilometer) Navajo Nation Reservation located in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah[1] |

In the 1831 Supreme Court of the United States case Cherokee Nation v. Georgia Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall wrote that Native Americans in the United States were "domestic dependent nations" whose relationship to the United States is like that of a "ward to its guardian". The case was a landmark decision which led to the United States recognizing over 574 federally recognized tribal governments and 326 Indian reservations which are legally classified as domestic dependent nations with tribal sovereignty rights.

Native American sovereignty and the Constitution

[edit]The United States Constitution mentions Native American tribes three times:

- Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 states that "Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States ... excluding Indians not taxed."[3] According to Story's Commentaries on the U.S. Constitution, "There were Indians, also, in several, and probably in most, of the states at that period, who were not treated as citizens, and yet, who did not form a part of independent communities or tribes, exercising general sovereignty and powers of government within the boundaries of the states."

- Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution states that "Congress shall have the power to regulate Commerce with foreign nations and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes",[4] determining that Indian tribes were separate from the federal government, the states, and foreign nations;[5] and

- The Fourteenth Amendment, Section 2 amends the apportionment of representatives in Article I, Section 2 above.[6]

These constitutional provisions, and subsequent interpretations by the Supreme Court (see below), are today often summarized in three principles of U.S. Indian law:[7][8][9]

- Territorial sovereignty: Tribal authority on Indian land is organic and is not granted by the states in which Indian lands are located.

- Plenary power doctrine: Congress, and not the Executive Branch or Judicial Branch, has ultimate authority with regard to matters affecting the Indian tribes. Federal courts give greater deference to Congress on Indian matters than on other subjects.

- Trust relationship: The federal government has a "duty to protect" the tribes, implying (courts have found) the necessary legislative and executive authorities to effect that duty.[10]

The Marshall Trilogy, 1823–1832

[edit]

The Marshall Trilogy is a set of three Supreme Court decisions in the early nineteenth century affirming the legal and political standing of Indian nations.

- Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), holding that private citizens could not purchase lands from Native Americans.

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), holding the Cherokee nation a "domestic dependent nation", with a relationship to the United States like that of a "ward to its guardian".

- Worcester v. Georgia (1832), which laid out the relationship between tribes and the state and federal governments, stating that the federal government was the sole authority to deal with Indian nations.[11]

Marshall’s phrasing "laid the groundwork for future protection of tribal sovereignty by Marshall and his immediate successors, but the characterization also created an opportunity for much later courts to discover limits to tribal sovereignty inherent in domestic dependent status. Marshall’s reference to tribes as 'wards' was to have an equally mixed history".[12]

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

[edit]

In June 1830, a delegation of Cherokee led by Chief John Ross and represented by William Wirt, a former United States attorney general in the Monroe and Adams administrations, were selected to bring a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. Backed by the supporters of Senators Daniel Webster and Theodore Frelinghuysen, the Cherokee Nation sought an injunction against Georgia. They argued that Georgia's state legislation had created laws aimed to "annihilate the Cherokees as a political society." The Cherokee claimed that Georgia’s actions violated U.S.–Cherokee treaties, the U.S. Constitution, and federal laws regulating interactions with Native tribes.

Wirt contended that the Cherokee Nation qualified as a "foreign nation" under the Constitution and therefore had standing to sue. He asked the Court to nullify Georgia’s laws extending over Cherokee territory. Georgia countered by arguing that the Cherokee lacked standing as a foreign nation, citing their absence of a constitution and centralized government. Wirt argued that "the Cherokee Nation [was] a foreign nation in the sense of our constitution and law" and was not subject to Georgia's jurisdiction.

Wirt asked the Supreme Court to void all Georgia laws extended over Cherokee lands because they violated the U.S. Constitution, United States–Cherokee treaties, and United States intercourse laws.

The Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, agreed to hear the case but declined to rule on the merits of the case. The Court determined that the framers of the Constitution did not consider the Indian Tribes as foreign nations but more as "domestic dependent nation[s]" and consequently the Cherokee Nation lacked the standing to sue as a "foreign" nation.

Key Opinions

[edit]Majority Opinion (Chief Justice John Marshall): Marshall concluded that Indian tribes, while retaining some sovereignty, were not foreign nations in the sense required to bring suit in federal court. He emphasized that the Constitution did not envision tribes as fully independent entities.[13]

Justice William Johnson (Concurring): Johnson described tribes as "nothing more than wandering hordes, held together only by ties of blood and habit, and having neither rules nor government beyond what is required in a savage state."[14] with no formal governance beyond blood ties and habits, underscoring their perceived lack of status as sovereign entities.

Dissenting Opinion (Justice Smith Thompson, joined by Justice Joseph Story): Thompson argued that the Cherokee Nation was a foreign state based on its ability to self-govern and enter treaties. He held that Georgia's laws violated federal treaties and acts of Congress, causing significant harm to the Cherokee. He supported the injunction against Georgia.

End of the Treaty Era

[edit]Indian Appropriations Act of 1871

[edit]Originally, the United States had recognized the Indian Tribes as independent nations, but after the Civil War, the U.S. suddenly changed its approach.[14]

The Indian Appropriations Act of 1871 had two significant sections. First, the Act ended United States recognition of additional Native American tribes or independent nations and prohibited additional treaties. Thus, it required the federal government no longer interact with the various tribes through treaties, but rather through statutes:

That hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty: Provided, further, that nothing herein contained shall be construed to invalidate or impair the obligation of any treaty heretofore lawfully made and ratified with any such Indian nation or tribe.

The 1871 Act also made it a federal crime to commit murder, manslaughter, rape, assault with intent to kill, arson, burglary, and larceny within any Territory of the United States.[citation needed]

Plenary Power

[edit]The 1871 Act was affirmed in 1886 by the U.S. Supreme Court, in United States v. Kagama, which affirmed that the Congress has plenary power over all Native American tribes within its borders by rationalization that "The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful ... is necessary to their protection as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell".[17] The Supreme Court affirmed that the U.S. Government "has the right and authority, instead of controlling them by treaties, to govern them by acts of Congress, they being within the geographical limit of the United States. ... The Indians owe no allegiance to a State within which their reservation may be established, and the State gives them no protection."[18]

The Allotment Era

[edit]The General Allotment Act (Dawes Act), 1887

[edit]Passed by Congress in 1887, the "Dawes Act" was named for Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, Chairman of the Senate's Indian Affairs Committee. It came as another crucial step in attacking the tribal aspect of the Indians of the time. In essence, the act broke up the land of most all tribes into modest parcels to be distributed to Indian families, and those remaining were auctioned off to white purchasers. Indians who accepted the farmland and became "civilized" were made American citizens. But the Act itself proved disastrous for Indians, as much tribal land was lost, and cultural traditions destroyed. Whites benefited the most; for example, when the government made 2 million acres (8,100 km2) of Indian lands available in Oklahoma, 50,000 white settlers poured in almost instantly to claim it all (in a period of one day, April 22, 1889).

Evolution of relationships: The evolution of the relationship between tribal governments and federal governments has been glued together through partnerships and agreements. Also running into problems of course such as finances which also led to not being able to have a stable social and political structure at the helm of these tribes or states.[19]

The Reorganization Era

[edit]Indian Reorganization Act, 1934

[edit]In 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act, codified as Title 25, Section 476 of the U.S. Code, allowed Indian nations to select from a catalogue of constitutional documents that enumerated powers for tribes and for tribal councils. Though the Act did not specifically recognize the Courts of Indian Offenses, 1934 is widely considered to be the year when tribal authority, rather than United States authority, gave the tribal courts legitimacy. John Collier and Nathan Margold wrote the solicitor's opinion, "Powers of Indian Tribes" which was issued October 25, 1934, and commented on the wording of the Indian Reorganization Act. This opinion stated that sovereign powers inhered in Indian tribes except for where they were restricted by Congress. The opinion stated that "Conquest has brought the Indian tribes under the control of Congress, but except as Congress has expressly restricted or limited the internal powers of sovereignty vested in the Indian tribes such powers are still vested in the respective tribes and may be exercised by their duly constituted organs of government."[20]

The Termination Era

[edit]Public Law 280, 1953

[edit]In 1953, Congress enacted Public Law 280, which gave some states extensive jurisdiction over the criminal and civil controversies involving Indians on Indian lands. Many, especially Indians, continue to believe the law unfair because it imposed a system of laws on the tribal nations without their approval.

In 1965, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit concluded that no law had ever extended provisions of the U.S. Constitution, including the right of habeas corpus, to tribal members brought before tribal courts. Still, the court concluded, "it is pure fiction to say that the Indian courts functioning in the Fort Belknap Indian community are not in part, at least, arms of the federal government. Originally they were created by federal executive and imposed upon the Indian community, and to this day the federal government still maintains a partial control over them." In the end however, the Ninth Circuit limited its decision to the particular reservation in question and stated, "it does not follow from our decision that the tribal court must comply with every constitutional restriction that is applicable to federal or state courts."

The Self-Determination Era

[edit]

Richard Nixon took office as president in 1969. From 1969 to 1974, the Richard Nixon administration made important changes to United States policy towards Native Americans through legislation and executive action. President Richard Nixon advocated a reversal of the long-standing policy of "termination" that had characterized relations between the U.S. federal government and American Indians in favor of "self-determination." The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act restructured indigenous governance in Alaska, creating a unique structure of Native Corporations. Some of the most notable instances of American Indian activism occurred under the Nixon Administration, including the Occupation of Alcatraz and the Occupation of Wounded Knee.

It was under his administration that Washington state Senator Henry M. Jackson and Senate Subcommittee on Indian Affairs aide Forrest J. Gerard were most active in their reform efforts. The work of Jackson and Gerard mirrored the demands of Indians for "self-determination." Nixon called for an end to termination and provided a direct endorsement of "self-determination."

In a 1970 address to Congress, Nixon articulated his vision of self-determination. He explained, "The time has come to break decisively with the past and to create the conditions for a new era in which the Indian future is determined by Indian acts and Indian decisions."[21] Nixon continued, "This policy of forced termination is wrong, in my judgment, for a number of reasons. First, the premises on which it rests are wrong. Termination implies that the federal government has taken on a trusteeship responsibility for Indian communities as an act of generosity toward a disadvantaged people and that it can therefore discontinue this responsibility on a unilateral basis whenever it sees fit."[21] Nixon's overt renunciation of the long-standing termination policy was the first of any President in the post-World War II era. While many modern courts in Indian nations today have established full faith and credit with state courts, the nations still have no direct access to U.S. courts. When an Indian nation files suit against a state in U.S. court, they do so with the approval of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In the modern legal era, the courts and Congress have, however, further refined the often competing jurisdictions of tribal nations, states and the United States in regard to Indian law.

Today the United States recognizes 574 Tribal nations, 229 of which are in Alaska.[22][23] The National Congress of American Indians explains, "Native peoples and governments have inherent rights and a political relationship with the U.S. government that does not derive from race or ethnicity."[23]

In the 1978 case of Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, the Supreme Court, in a 6–2 opinion authored by Justice William Rehnquist, concluded that tribal courts do not have jurisdiction over non-Indians (the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court at that time, Warren Burger, and Justice Thurgood Marshall filed a dissenting opinion). But the case left unanswered some questions, including whether tribal courts could use criminal contempt powers against non-Indians to maintain decorum in the courtroom, or whether tribal courts could subpoena non-Indians.

A 1981 case, Montana v. United States, clarified that tribal nations possess inherent power over their internal affairs, and civil authority over non-members on fee-simple lands within its reservation when their "conduct threatens or has some direct effect on the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the tribe."

Other cases of those years precluded states from interfering with tribal nations' sovereignty. Tribal sovereignty is dependent on, and subordinate to, only the federal government, not states, under Washington v. Confederated Tribes of Colville Indian Reservation (1980). Tribes are sovereign over tribal members and tribal land, under United States v. Mazurie (1975).[11]

In Duro v. Reina, 495 U.S. 676 (1990), the Supreme Court held that a tribal court does not have criminal jurisdiction over a non-member Indian, but that tribes "also possess their traditional and undisputed power to exclude persons who they deem to be undesirable from tribal lands. ... Tribal law enforcement authorities have the power if necessary, to eject them. Where jurisdiction to try and punish an offender rests outside the tribe, tribal officers may exercise their power to detain and transport him to the proper authorities." In response to this decision, Congress passed the 'Duro Fix', which recognizes the power of tribes to exercise criminal jurisdiction within their reservations over all Indians, including non-members. The Duro Fix was upheld by the Supreme Court in United States v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193 (2004).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Frequently Asked Questions, Bureau of Indian Affairs". Department of the Interior. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Navajo Population Profile 2010 U.S. Census" (PDF). Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ Constitution of the United States of America: Article. I.

- ^ American Indian Policy Center. 2005. St. Paul, MN. 4 October 2008

- ^ Cherokee Nations v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831)

- ^ Additional amendments to the United States Constitution

- ^ Charles F. Wilkinson, Indian tribes as sovereign governments: a sourcebook on federal-tribal history, law, and policy, AIRI Press, 1988

- ^ Conference of Western Attorneys General, American Indian Law Deskbook, University Press of Colorado, 2004

- ^ N. Bruce Duthu, American Indians and the Law, Penguin/Viking, 2008

- ^ Robert J. McCarthy, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Federal Trust Obligation to American Indians, 19 BYU J. PUB. L. 1 (December, 2004)

- ^ a b Miller, Robert J. (March 18, 2021). "The Most Significant Indian Law Decision in a Century | The Regulatory Review". The Regulatory Review. University of Pennsylvania Law School. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Canby Jr., William C. American Indian Law in a Nutshell (Nutshells). p. 20.>

- ^ "Worcester v. Georgia." Oyez. Accessed 03 Aug. 2014. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1832/1832_2

- ^ a b Cherokee Nation v Georgia 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) at 190.

- ^ Onecle (November 8, 2005). "Indian Treaties". Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ 25 U.S.C. § 71. Indian Appropriation Act of March 3, 1871, 16 Stat. 544, 566

- ^ "U.S. v Kagama, 118 U.S. 375 (1886), Filed May 10, 1886". FindLaw, a Thomson Reuters business. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "United States v. Kagama – 118 U.S. 375 (1886)". Justia. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "Historical Tribal Sovereignty & Relations | Native American Financial Services Association". August 7, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Margold, Nathan R. "Powers of Indian Tribes". Solicitor's Opinions. University of Oklahoma College of Law. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Richard Nixon Special Message to Congress on Indian Affairs". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ "Native American Policies". U.S. Department of Justice. June 16, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "Tribal Nations & the United States: An Introduction". National Congress of American Indians. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Blackhawk, Ned. (2023). The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Canby, William C. Jr. (2009). American Indian Law in a Nutshell. Eagan, MN: West Publishing. ISBN 978-0-314-19519-7.

- DeJong, David H. (2015) American Indian Treaties: A Guide to Ratified and Unratified Colonial, United States, State, Foreign, and Intertribal Treaties and Agreements, 1607–1911. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1-60781-425-2

- Finkelman, Paul; Garrison, Tim Alan (2008). Encyclopedia of United States Indian Policy and Law. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1-933116-98-3.

- Pevar, Stephan E. (2004). The Rights of Indians and Tribes: The Authoritative ACLU Guide to Indian and Tribal Rights. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-6718-4.

- Pommershiem, Frank (1997). Braid of Feathers: American Indian Law and Contemporary Tribal Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20894-3.

- Prucha, Francis Paul, ed. Documents of United States Indian Policy (3rd ed. 2000)

- Prucha, Francis Paul. American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly (1997) excerpt and text search

- Prucha, Francis Paul. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians (abridged edition, 1986)

- McCarthy, Robert J. "The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Federal Trust Obligation to American Indians," 19 BYU J. PUB. L. 1 (December, 2004).

- Ulrich, Roberta (2010). American Indian Nations from Termination to Restoration, 1953-2006. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3364-5.

- Wilkinson, Charles (1988). American Indians, Time, and the Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitutional Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04136-1.

- Wilkins, David (2011). American Indian Politics and the American Political System. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9306-1.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

External links

[edit]- Kussel, Wm. F. Jr. Tribal Sovereignty and Jurisdiction (It's a Matter of Trust) Archived July 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- The Avalon Project: Treaties Between the United States and Native Americans

- Cherokee Nation v. the State of Georgia Archived December 2, 2003, at the Wayback Machine, 1831

- Prygoski, Philip J. From Marshall to Marshall: The Supreme Court's Changing Stance on Tribal Sovereignty

- From War to Self Determination, the Bureau of Indian Affairs

- NiiSka, Clara, Indian Courts, A Brief History, parts I Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, II Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, and III Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Public Law 280

- Religious Freedom with Raptors at archive.today (archived 2013-01-10) – details racism and attack on tribal sovereignty regarding eagle feathers

- San Diego Union Tribune, 17 December 2007: Tribal justice not always fair, critics contend (Tort cases tried in tribal courts)

- Sovereignty Revisited: International Law and Parallel Sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples