Donovan

Donovan | |

|---|---|

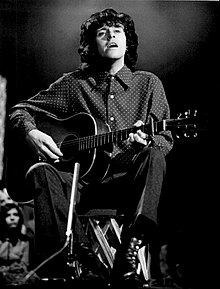

Donovan performing on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1969 | |

| Born | Donovan Phillips Leitch 10 May 1946 |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1964–present |

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Enid Karl (1966–70) |

| Children | 5; including Donovan Leitch and Ione Skye |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Website | donovan |

Donovan Phillips Leitch (born 10 May 1946), known mononymously as Donovan, is a Scottish musician, songwriter and record producer. He emerged from the British folk scene in early 1965, and subsequently scored multiple international hit singles and albums during the late 1960s. His work became emblematic of the flower power era with its blend of folk, pop, psychedelic rock, and jazz stylings.

Donovan first achieved recognition with live performances on the pop TV series Ready Steady Go! in 1965. Having signed with Pye Records that year, he recorded singles and two albums in the folk vein for Hickory Records, scoring three UK hit singles: "Catch the Wind", "Colours" and "Universal Soldier", the last written by Buffy Sainte-Marie. He then signed to CBS/Epic in the US and became more successful internationally, beginning a long collaboration with British record producer Mickie Most. In September 1966, "Sunshine Superman" topped America's Billboard Hot 100 chart for one week and went to No. 2 in Britain, followed by "Mellow Yellow" at US No. 2 in December 1966, then 1968's "Hurdy Gurdy Man" in the top 5 in both countries, and then "Atlantis", which reached US No. 7 in May 1969. The compilation Donovan's Greatest Hits was released in March 1969 and peaked at No. 4 on the Billboard 200.[1]

Donovan became a friend of other prominent musicians such as Joan Baez, Brian Jones, and the Beatles. He taught John Lennon a finger-picking guitar style in 1968 that Lennon employed in "Dear Prudence", "Julia", "Happiness Is a Warm Gun", and other songs.[2] His backing musicians included the Jeff Beck Group, and John Bonham, Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, who later rose to fame as members of Led Zeppelin. Donovan's commercial fortunes waned after parting with Most in 1969, and he left the industry for a time.

Donovan continued to perform and record intermittently in the 1970s and 1980s. His musical style and hippie image were scorned by critics, especially after the rise of punk rock. His performing and recording became sporadic until a revival in the 1990s with the emergence of Britain's rave scene and in 1994, he moved permanently to Ireland where he still lives.[3] In 1996 he recorded the album Sutras with producer Rick Rubin and in 2004 made the album Beat Cafe. Donovan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012 and the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2014.

Early life

[edit]Donovan was born on 10 May 1946, in Maryhill, Glasgow,[4][5] to Donald and Winifred (née Phillips) Leitch. His grandmothers were Irish.[6][7] He contracted polio as a child. The disease and treatment left him with a limp.[8] His family moved to the new town of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. Influenced by his family's love of folk music, he began playing the guitar at 14. He enrolled in art school but soon dropped out, to live out his beatnik aspirations by going on the road.[9]

Music career

[edit]1964–66: Rise to fame

[edit]

Returning to Hatfield, Donovan spent several months playing in local clubs, absorbing the folk scene around his home in St Albans, learning the crosspicking guitar technique from local players such as Mac MacLeod and Mick Softley and writing his first songs. In 1964, he travelled to Manchester with Gypsy Dave, then spent the summer in Torquay, Devon. In Torquay he stayed with Mac MacLeod and took up busking, studying the guitar, and learning traditional folk and blues.[10][11]

In late 1964, Donovan was offered a management and publishing contract by Peter Eden and Geoff Stephens of Pye Records in London, for which he recorded a 10-track demo tape which included the original of his first single, "Catch the Wind", and "Josie". The first song revealed the influence of Woody Guthrie and Ramblin' Jack Elliott, who had also influenced Bob Dylan. Dylan comparisons followed for some time.[12] In an interview with KFOK radio in the US on 14 June 2005, MacLeod said: "The press were fond of calling Donovan a Dylan clone as they had both been influenced by the same sources: Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Jesse Fuller, Woody Guthrie, and many more."[citation needed]

While recording the demo, Donovan befriended Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, who was recording nearby. He had recently met Jones' ex-girlfriend, Linda Lawrence, who is the mother of Jones' son, Julian Brian (Jones) Leitch.[13] The on-off romantic relationship that developed over five years was a force in Donovan's career. She influenced Donovan's music but refused to marry him and she moved to the United States for several years in the late 1960s. They met by chance in 1970 and married soon after. Donovan had other relationships – one of which resulted in the birth of his first two children, Donovan Leitch and Ione Skye, both of whom became actors.

Donovan and Dylan

[edit]During Bob Dylan's trip to the UK in the spring of 1965, the British music press were making comparisons of the two singer-songwriters which they presented as a rivalry. This prompted The Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones to say,

We've been watching Donovan too. He isn't too bad a singer but his stuff sounds like Dylan's. His 'Catch The Wind' sounds like 'Chimes of Freedom'. He's got a song, 'Hey Tangerine Eyes' and it sounds like Dylan's 'Mr. Tambourine Man'.[14]

Donovan is the undercurrent In D. A. Pennebaker's film Dont Look Back documenting Dylan's tour. Near the start of the film, Dylan opens a newspaper and exclaims, "Donovan? Who is this Donovan?" and Alan Price from The Animals spurred the rivalry on by telling Dylan that Donovan is a better guitar player, but that he had only been around for three months. Throughout the film Donovan's name is seen next to Dylan's on newspaper headlines and on posters in the background, and Dylan and his friends refer to him consistently.

Donovan finally appears in the second half of the film, along with Derroll Adams, in Dylan's suite at the Savoy Hotel despite Donovan's management refusing to allow journalists to be present, saying they did not want "any stunt on the lines of the disciple meeting the messiah".[15] According to Pennebaker, Dylan told him not to film the encounter, and Donovan played a song that sounded just like "Mr. Tambourine Man" but with different words. When confronted with lifting his tune, Donovan said that he thought it was an old folk song.[16] Once the camera rolled, Donovan plays his song "To Sing For You" and then asks Dylan to play "Baby Blue". Dylan later told Melody Maker: "He played some songs to me. ... I like him. ... He's a nice guy." Melody Maker noted that Dylan had mentioned Donovan in his song "Talking World War Three Blues" and that the crowd had jeered, to which Dylan had responded backstage: "I didn't mean to put the guy down in my songs. I just did it for a joke, that's all."

In an interview for the BBC in 2001 to mark Dylan's 60th birthday, Donovan acknowledged Dylan as an influence early in his career while distancing himself from "Dylan clone" allegations:

The one who really taught us to play and learn all the traditional songs was Martin Carthy – who incidentally was contacted by Dylan when Bob first came to the UK. Bob was influenced, as all American folk artists are, by the Celtic music of Ireland, Scotland and England. But in 1962 we folk Brits were also being influenced by some folk Blues and the American folk-exponents of our Celtic Heritage ... Dylan appeared after Woody [Guthrie], Pete [Seeger] and Joanie [Baez] had conquered our hearts, and he sounded like a cowboy at first but I knew where he got his stuff – it was Woody at first, then it was Jack Kerouac and the stream-of-consciousness poetry which moved him along. But when I heard 'Blowin' in the Wind' it was the clarion call to the new generation – and we artists were encouraged to be as brave in writing our thoughts in music ... We were not captured by his influence, we were encouraged to mimic him – and remember every British band from the Stones to the Beatles were copying note for note, lick for lick, all the American pop and blues artists – this is the way young artists learn. There's no shame in mimicking a hero or two – it flexes the creative muscles and tones the quality of our composition and technique. It was not only Dylan who influenced us – for me he was a spearhead into protest, and we all had a go at his style. I sounded like him for five minutes – others made a career of his sound. Like troubadours, Bob and I can write about any facet of the human condition. To be compared was natural, but I am not a copyist.[17]

Collaboration with Mickie Most

[edit]In late 1965, Donovan split with his original management and signed with Ashley Kozak, who was working for Brian Epstein's NEMS Enterprises. Kozak introduced Donovan to American businessman Allen Klein (later manager of the Rolling Stones and, in their final months, the Beatles).[18] Klein in turn introduced Donovan to producer Mickie Most,[19] who had chart-topping productions with the Animals, Lulu, and Herman's Hermits. Most produced all Donovan's recordings during this period, although Donovan said in his autobiography that some recordings were self-produced, with little input from Most. Their collaboration produced successful singles and albums, recorded with London session players including Big Jim Sullivan,[20] Jack Bruce,[21] Danny Thompson,[22] and future Led Zeppelin members John Paul Jones and Jimmy Page.[23]

Many of Donovan's late 1960s recordings featured musicians including his key musical collaborator John Cameron on piano, Danny Thompson (from Pentangle) or Spike Heatley on upright bass, Tony Carr on drums and congas and Harold McNair on saxophone and flute. Carr's conga style and McNair's flute playing are a feature of many recordings. Cameron, McNair and Carr also accompanied Donovan on several concert tours and can be heard on his 1968 live album Donovan in Concert.

Sunshine Superman

[edit]

By 1966, Donovan had shed the Dylan/Guthrie influences and become one of the first British pop musicians to adopt flower power. He immersed himself in jazz, blues, Eastern music, and the new generation of counterculture-era US West Coast bands such as Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead. He was entering his most creative phase as a songwriter and recording artist, working with Mickie Most and with arranger, musician, and jazz fan John Cameron. Their first collaboration was Sunshine Superman, one of the first psychedelic pop records.[19]

Donovan's rise stalled in December 1965 when Billboard broke news of the impending production deal between Klein, Most, and Donovan, and then reported that Donovan was to sign with Epic Records in the US. Despite Kozak's denials, Pye Records dropped the single and a contract dispute ensued, because Pye had a US licensing arrangement with Warner Bros. Records. As a result, the UK release of the Sunshine Superman LP was delayed for months, robbing it of the impact it would have had. Another outcome was that the UK and US versions of this and later albums differed – three of his Epic LPs were not released in the UK, and Sunshine Superman was issued in a different form in each country. Several tracks on his late 1960s Epic (US) LPs were not released in the UK for many years. The legal dispute continued into early 1966. During the hiatus, Donovan holidayed in Greece, where he wrote "Writer in the Sun",[24] inspired by rumours that his recording career was over. He toured the US and appeared on episode 23 of Pete Seeger's television show Rainbow Quest in 1966 with Shawn Phillips and Rev. Gary Davis. After his return to London, he developed his friendship with Paul McCartney and contributed the line "sky of blue and sea of green" to "Yellow Submarine".

By spring 1966, the American contract problems had been resolved, and Donovan signed a $100,000 deal with Epic Records. Donovan and Most went to CBS Studios in Los Angeles, where they recorded tracks for an LP, much composed during the preceding year. Although folk elements were prominent, the album showed increasing influence of jazz, American west coast psychedelia and folk rock – especially the Byrds. The LP sessions were completed in May, and "Sunshine Superman" was released in the US as a single in June. It was a success, selling 800,000 in six weeks and reaching No. 1. It went on to sell over one million, and was awarded a gold disc.[25] The LP followed in August, preceded by orders of 250,000 copies, reached No. 11 on the US album chart and sold over half a million.[25]

The US version of the Sunshine Superman album features instruments including acoustic bass, sitar, saxophone, tablas and congas, harpsichord, strings and oboe. Highlights include the swinging "The Fat Angel", which Donovan's book confirms was written for Cass Elliot of the Mamas & the Papas. The song is notable for naming the Jefferson Airplane before they became known internationally and before Grace Slick joined. Other tracks include "Bert's Blues" (a tribute to Bert Jansch), "Guinevere", and "Legend of a Girl Child Linda", a track featuring voice, acoustic guitar and a small orchestra for over six minutes.[26]

The album also features the sitar, which was played by American folk-rock singer Shawn Phillips. Donovan met Phillips in London in 1965, and he became a friend and early collaborator, playing acoustic guitar and sitar on recordings including Sunshine Superman as well as accompanying Donovan at concerts and on Pete Seeger's TV show. Creatively, Phillips served as a silent partner in the gestation of many of Donovan's songs from the era, with the singer later acknowledging that Phillips primarily composed "Season of the Witch".[27] Several songs including the title track had a harder edge. The driving, jazzy "The Trip", named after a Los Angeles club name, chronicled an LSD trip during his time in L.A. and is loaded with references to his sojourn on the West Coast, and names Dylan and Baez. The third "heavy" song was "Season of the Witch".[citation needed] Recorded with American and British session players, it features Donovan's first recorded performance on electric guitar. The song was covered by Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger and the Trinity on their first LP in 1967, and Al Kooper and Stephen Stills recorded an 11-minute version on the 1968 album, Super Session. Donovan's version is also in the closing sequence of the Gus Van Sant film, To Die For. [citation needed]

Because of earlier contractual problems, the UK version of Sunshine Superman LP was not released for another nine months. This was a compilation of tracks from the US albums Sunshine Superman and Mellow Yellow. Donovan did not choose the tracks.[citation needed]

Mellow Yellow

[edit]

On 24 October 1966, Epic released the single "Mellow Yellow", arranged by John Paul Jones and purportedly featuring Paul McCartney on backing vocals, but not in the chorus.[19] In his autobiography Donovan explained "electrical banana" was a reference to a "yellow-coloured vibrator".[28] The song became Donovan's signature tune in the US and reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100, No. 3 on the Cash Box chart, and earned a gold record award for sales of more than one million in the US.[25]

Through the first half of 1967, Donovan worked on a double-album studio project, which he produced. In January he gave a concert at the Royal Albert Hall accompanied by a ballerina who danced during a 12-minute performance of "Golden Apples". On 14 January, New Musical Express reported he was to write incidental music for a National Theatre production of As You Like It, but this did not come to fruition. His version of "Under the Greenwood Tree" did appear on "A Gift from a Flower to a Garden".

In March Epic released the Mellow Yellow LP (not released in the UK), which reached No. 14 in the US album charts, plus a non-album single, "Epistle to Dippy", a Top 20 hit in the US. Written as an open letter to a school friend, the song had a pacifist message as well as psychedelic imagery. The real "Dippy" was in the British Army in Malaysia. According to Brian Hogg, who wrote the liner notes for the Donovan boxed set Troubadour, Dippy heard the song, contacted Donovan and left the army. On 9 February 1967, Donovan was among guests invited by the Beatles to Abbey Road Studios for the orchestral overdub for "A Day in the Life", the finale to Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[29]

Arrest

[edit]On 10 June 1966,[30] Donovan became the first high-profile British pop star to be arrested for possession of cannabis.[8][31] Donovan's drug use was mostly restricted to cannabis, with occasional use of LSD and mescaline.[citation needed] His LSD use is thought to be referenced indirectly in some of his lyrics.[8] Public attention was drawn to his marijuana use by the TV documentary A Boy Called Donovan in early 1966, which showed the singer and friends smoking cannabis at a party thrown by the film crew. Donovan's arrest proved to be the first in a long series involving the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. In early 1967, Donovan was subject of an exposé in the News of the World.[32]

According to Donovan, the article was based on an interview by an ex-girlfriend of his friend Gypsy Dave. The article was the first in a three-part series, Drugs & Pop Stars – Facts That Will Shock You. It was quickly shown some claims were false. A News of the World reporter claimed to have spent an evening with Mick Jagger, who allegedly discussed his drug use and offered drugs to companions. He had mistaken Brian Jones for Jagger, and Jagger sued the newspaper for libel. Among other supposed revelations were claims that Donovan and stars including members of The Who, Cream, The Rolling Stones and The Moody Blues regularly smoked marijuana, used other drugs, and held parties where the recently banned hallucinogen LSD was used, specifically naming the Who's Pete Townshend and Cream's Ginger Baker.

It emerged later that the News of the World reporters were passing information to the police. In the late 1990s, The Guardian said News of the World reporters had alerted police to the party at Keith Richards's home, which was raided on 12 February 1967. Although Donovan's was not as sensational as the later arrests of Jagger and Richards, he was refused entry to the US until late 1967. He could not appear at the Monterey International Pop Festival in June that year.[33]

1967–69: International success

[edit]In July 1967, Epic released "There Is a Mountain", which just missed the US top ten and was later used as the basis for the Allman Brothers Band's "Mountain Jam". In September, Donovan toured the US, backed by a jazz group and accompanied by his father, who introduced the show. Later that month, Epic released Donovan's fifth album, a set titled, A Gift from a Flower to a Garden, the first rock music box set and only the third pop-rock double album released. It was split into halves. The first, Wear Your Love Like Heaven, was for people of his generation who would one day be parents; the second, For Little Ones, was songs Donovan had written for coming generations. Worried it might be a poor seller, Epic boss Clive Davis also insisted the albums be split and sold separately in the US (the "Wear Your Love Like Heaven" album cover was photographed at Bodiam Castle), but his fears were unfounded – although it took time, the original boxed set sold steadily, eventually peaking at 19 in the US album chart and achieving gold record status in the US in early 1970.

The psychedelic and mystical overtones were unmistakable – the front cover featured an infra-red photograph by Karl Ferris showing Donovan at Bodiam Castle, dressed in a robe, holding flowers and peacock feathers, while the back photo showed him holding hands with Indian guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. The liner notes included an appeal for young people to give up drugs. His disavowal of drugs came after his time with the Maharishi in Rishikesh, a topic discussed in a two-part interview for the first two issues of Rolling Stone.[34]

In late 1967 Donovan contributed two songs to the Ken Loach film Poor Cow. "Be Not Too Hard" was a musical setting of Christopher Logue's poem September Song, and was later recorded by such artists as Joan Baez and Shusha Guppy. The title track, originally entitled "Poor Love", was the B-side of his next single, "Jennifer Juniper", which was inspired by Jenny Boyd, sister of George Harrison's wife, Pattie Boyd and was another top 40 hit in the US. Donovan developed interest in eastern mysticism and claims to have interested the Beatles in transcendental meditation.[citation needed]

In early 1968 he was part of the group that traveled to the ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Rishikesh. The visit gained worldwide attention thanks to the presence of all four Beatles as well as Beach Boys lead singer Mike Love, as well as actress Mia Farrow and her sister Prudence (who inspired Lennon to write "Dear Prudence"). According to a 1968 Paul McCartney interview with Radio Luxembourg,[35] it was during this time that Donovan taught Lennon and McCartney finger-picking guitar styles including the clawhammer, which he had learned from Mac MacLeod. Lennon used this technique on songs including "Dear Prudence", "Julia", "Happiness is a Warm Gun" and "Look at Me", and McCartney with "Blackbird" and "Mother Nature's Son".[36]

Donovan's next single, in May 1968, was the psychedelic "Hurdy Gurdy Man". The liner notes from EMI's reissues say the song was intended for Mac MacLeod, who had a heavy rock band called Hurdy Gurdy. After hearing MacLeod's version, Donovan considered giving it to Jimi Hendrix, but when Most heard it, he convinced Donovan to record it himself. Donovan tried to get Hendrix to play, but he was on tour. Jimmy Page played electric guitar in some studio sessions and is credited with playing on the song.[37][38] Alternatively, it is credited to Alan Parker.[citation needed]

Donovan credits Page and "Allen Hollsworth" (a misspelling of Allan Holdsworth) as the "guitar wizards" for the song, saying they created "a new kind of metal folk".[39]

Since John Bonham and John Paul Jones also played, Donovan said perhaps the session inspired the formation of Led Zeppelin.[39] The heavier sound of "Hurdy Gurdy Man" was an attempt by Most and Donovan to reach a wider audience in the US, where hard-rock groups like Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience were having an impact. The song became one of Donovan's biggest hits, making the Top 5 in the UK and the US, and the Top 10 in Australia.[citation needed]

In July 1968, Epic released Donovan in Concert, the recording of his Anaheim concert in September 1967. The cover featured only a painting by Fleur Cowles (with neither the artist's name nor the title). The album contained two of his big hits and songs which would have been new to the audience. The expanded double CD from 2006 contained "Epistle To Derroll", a tribute to one of his formative influences, Derroll Adams. The album also includes extended group arrangements of "Young Girl Blues" and "The Pebble and the Man", a song later reworked and retitled as "Happiness Runs". In the summer of 1968, Donovan worked on a second LP of children's songs, released in 1971 as the double album, HMS Donovan. In September, Epic released a single, "Laléna", a subdued acoustic ballad which reached the low 30s in the US. The album The Hurdy Gurdy Man followed (not released in the UK), continuing the style of the Mellow Yellow LP, and reached 20 in the US, despite containing two earlier hits, the title track and "Jennifer Juniper".[citation needed]

After another US tour in the autumn he collaborated with Paul McCartney, who was producing Postcard, the debut LP by Welsh singer Mary Hopkin. Hopkin covered three Donovan songs: "Lord Of The Reedy River", "Happiness Runs" and "Voyage of the Moon". McCartney returned the favour by playing tambourine and singing backing vocals on Donovan's next single, "Atlantis", which was released in the UK (with "I Love My Shirt" as the B-side) in late November and reached 23.[40]

Early in 1969, the comedy film If It's Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium featured music by Donovan; the title tune was written by him and sung by J. P. Rags, and he also performed "Lord of the Reedy River" in the film as a singer at a youth hostel. On 20 January, Epic released the single, "To Susan on the West Coast Waiting", with "Atlantis" as the B-side. The A-side, a gentle calypso-styled song, contained another anti-war message, and became a moderate Top 40 US hit. However, when DJs in America and Australia flipped it and began playing "Atlantis", that became a hit. The gentle "Atlantis" later formed the backdrop to a violent scene in Martin Scorsese's 1990 film GoodFellas. "Atlantis" was revived in 2000 for an episode of Futurama titled "The Deep South" (2ACV12) which aired on 16 April that year. For this episode Donovan recorded a satirical version of the song describing the Lost City of Atlanta which featured in the episode.

In March 1969 (too soon to include "Atlantis"), Epic and Pye released Donovan's Greatest Hits, which included four previous singles – "Epistle To Dippy", "There is a Mountain", "Jennifer Juniper" and "Laléna", as well as rerecorded versions of "Colours" and "Catch The Wind" (which had been unavailable to Epic because of Donovan's contractual problems) and stereo versions of "Sunshine Superman" (previously unissued full length version) and "Season of the Witch". It became the most successful album of his career; it reached 4 in the US, became a million-selling gold record, and stayed on the Billboard album chart for more than a year. On 26 June 1969 the track "Barabajagal (Love Is Hot)" (recorded May 1969), which gained him a following on the rave scene decades later, was released, reaching 12 in the UK but charting less strongly in the US. This time he was backed by the original Jeff Beck Group, featuring Beck on lead guitar, Ronnie Wood on bass, Nicky Hopkins on piano, and Micky Waller on drums. The Beck group was under contract to Most and it was Most's idea to team them with Donovan to bring a heavier sound to Donovan's work, while introducing a lyrical edge to Beck's.[citation needed]

On 7 July 1969, Donovan performed at the first show in the second season of free rock concerts in Hyde Park, London, which also featured Blind Faith, Richie Havens, the Edgar Broughton Band and the Third Ear Band. In September 1969, the "Barabajagal" album reached 23 in the US. Only the recent "Barabajagal"/"Trudi" single and "Superlungs My Supergirl" were 1969 recordings, the remaining tracks [clarification needed] were from sessions in London in May 1968 and in Los Angeles in November 1968. [citation needed]

In the late 1960s to the early 1970s he lived at Stein, on the Isle of Skye, where he and a group of followers formed a commune and where he was visited by George Harrison. He named his daughter, born 1970, Ione Skye.[41][42]

1970s: Changes

[edit]In late 1969, the relationship with Most ended after an argument over an unidentified recording session in Los Angeles. In the 1995 BBC Radio 2 The Donovan Story, Most recounted:

The only time we ever fell out was in Los Angeles when there was all these, I suppose, big stars of their day, the Stephen Stillses and the Mama Casses, all at the session and nothing was actually being played. Somebody brought some dope into the session and I stopped the session and slung them out. You know you need someone to say, "it's my session, I'm paying for it." We fell out over that.[43]

Open Road band

[edit]Donovan said he wanted to record with someone else, and he and Most did not work together again until Cosmic Wheels (1973). After the rift, Donovan spent two months writing and recording the album Open Road as a member of the rock trio Open Road. Stripping the sound of Most's heavy studio productions down to stuff that could be played by a live band, Donovan dubbed the sound "Celtic Rock". The album peaked at No. 16 in the U.S., the third-highest of any of his full-length releases to date, but as his concert appearances became less frequent and new artists and styles of popular music began to emerge, his commercial success began to decline. Donovan said:

I was exhausted and looking for roots and new directions. I checked into Morgan Studios in London and stayed a long while creating Open Road and the HMS Donovan sessions. Downstairs was McCartney, doing his solo album. I had left Mickie after great years together. The new decade dawned and I had accomplished everything any young singer-songwriter could achieve. What else was there to do but to experiment beyond the fame and into the new life, regardless of the result?[43]

Donovan's plan for Open Road was to tour the world for a year, beginning with a boat voyage around the Aegean Sea, documented in the 1970 film There is an Ocean. This was partially on the advice from his management to go into tax exile, during which he was not to set foot in the UK until April 1971, but after touring to France, Italy, Russia, and Japan, he cut the tour short:

I travelled to Japan and was set to stay out of the UK for a year and earn the largest fees yet for a solo performer, and all tax-free. At the time the UK tax for us was 98%. During that Japanese tour I had a gentle breakdown, which made me decide to break the tax exile. Millions were at stake. My father, my agent, they pleaded for me not to step onto the BOAC jet bound for London. I did and went back to my little cottage in the woods. Two days later a young woman came seeking a cottage to rent. It was Linda.[43]

The band would continue without Donovan, adding new members, touring and releasing the album Windy Daze in 1971 before disbanding in 1972.[44][45]

Reunions with Linda Lawrence and Mickie Most

[edit]After this reunion, Donovan and Linda married on 2 October 1970 at Windsor register office and honeymooned in the Caribbean. Donovan dropped out of the round of tour promotion and concentrated on writing, recording and his family. The largely self-produced children's album HMS Donovan in 1971, went unreleased in the US and did not gain a wide audience. During an 18-month tax exile in Ireland (1971–72), he wrote for the 1972 film The Pied Piper in the title role, and for Brother Sun, Sister Moon (1972). The title song from the Zeffirelli film provided Donovan with a publishing windfall in 1974 when it was covered as the B-side of the million-selling US top 5 hit "The Lord's Prayer", by Australia's singing nun, Sister Janet Mead.

After a new deal with Epic, Donovan reunited with Mickie Most in early 1973, resulting in the LP Cosmic Wheels, which featured arrangements by Chris Spedding.[43] It was his last chart success, reaching the top 40 in America and Britain. Late in the year, he released Essence To Essence, produced by Andrew Loog Oldham, and a live album recorded and released only in Japan, which featured an extended version of "Hurdy Gurdy Man", including an additional verse written by George Harrison in Rishikesh.[46] While recording the album, Alice Cooper invited Donovan to share lead vocals on his song "Billion Dollar Babies".[citation needed]

Cosmic Wheels was followed up by two albums that same year: his second concert album, Live in Japan: Spring Tour 1973, and the more introspective Essence to Essence. His last two albums for Epic Records were 7-Tease (1974) and Slow Down World (1976). In 1977, he opened for Yes on their six-month tour of North America and Europe following the release of Going for the One (1977). The 1978 LP, Donovan was on Most's RAK Records in the UK and on Clive Davis' new Arista Records in the US; it reunited him for the last time with Most and Cameron, but was not well received at the height of the new wave and did not chart.[citation needed]

1980s–1990s

[edit]The punk era (1976–1980) provoked a backlash in Britain against the optimism and whimsy of the hippie era, of which Donovan was a prime example. The word "hippie" became pejorative, and Donovan's fortunes suffered.[citation needed] In this period, he released the albums Neutronica (1980), Love Is Only Feeling (1981), and Lady of the Stars (1984), and guest-starred on Stars on Ice, a half-hour variety show on ice produced by CTV in Toronto. There was a respite when he appeared alongside Sting, Phil Collins, Bob Geldof, Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck in the Amnesty International benefit show The Secret Policeman's Other Ball. Accompanied by Danny Thompson, Donovan performed several hits including "Sunshine Superman", "Mellow Yellow", "Colours", "Universal Soldier" and "Catch the Wind". He was also in the performance of Dylan's "I Shall Be Released" for the show's finale. Donovan also appeared at the Glastonbury Festival on 18 June 1989 with the band Ozric Tentacles accompanying him onstage.

In 1990, Donovan released a live album featuring new performances of his classic songs. In 1991, Nettwerk released a tribute album to Donovan, Island of Circles. Sony's 2-CD boxed set Troubadour: The Definitive Collection 1964–1976 (1992) continued the restoration of his reputation, and was followed by the 1994 release of Four Donovan Originals, which saw his four classic Epic LPs on CD in their original form for the first time in the UK. He found an ally in rap producer and Def Jam label owner Rick Rubin and recorded the album Sutras for Rubin's American Recordings label.[19]

2000s

[edit]

In 2000, Donovan narrated and played himself in the Futurama episode "The Deep South" on 16 April with a parody of the song "Atlantis".[citation needed]

A new album, Beat Cafe, on Appleseed Records in 2004, marked a return to the jazzy sound of his 1960s recordings and featured bassist Danny Thompson and drummer Jim Keltner, with production by John Chelew (The Blind Boys of Alabama). At a series of Beat Cafe performances in New York, Richard Barone (The Bongos) joined Donovan to sing and read passages from Allen Ginsberg's Howl.

In May 2004, Donovan played "Sunshine Superman" at the wedding concert for the Crown Prince and Crown Princess of Denmark. He released his early demo tapes, Sixty Four, and a re-recording of the Brother Sun, Sister Moon soundtrack on iTunes. A set of his Mickie Most albums was released on 9 May 2005. This EMI set has extra tracks including another song recorded with the Jeff Beck Group. In 2005, his autobiography The Hurdy Gurdy Man was published. In May/June 2005, Donovan toured the UK (Beat Cafe Tour) and Europe with Tom Mansi on double bass, former Damned drummer Rat Scabies and Flipron keyboard player, Joe Atkinson.

In 2006, Donovan played British festivals and two dates at Camden's The Jazz Cafe, London.

In January 2007, Donovan played at the Kennedy Center, in Washington, DC; at Alice Tully Hall, in New York City; and at the Kodak Theatre, in Los Angeles, in conjunction with a presentation by filmmaker David Lynch supporting the David Lynch Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education and world peace. The concert at the Kodak Theatre was filmed by Raven Productions and broadcast on public television as a pledge drive. Donovan's partnership with the David Lynch Foundation saw him performing concerts through October 2007, as well as giving presentations about Transcendental meditation. He appeared at Maharishi University of Management in Fairfield, Iowa, in May 2007,[47] and toured the UK with Lynch in October 2007.[48]

In March 2007, Donovan played two shows at the South by Southwest music festival in Austin, Texas. He had planned a spring 2007 release of an album, along with a UK tour, but announced the tour was cancelled and the album delayed. He said was in good health and gave no reason for the cancellation.[citation needed]

In April 2007, Donovan presented a three-part series on Ravi Shankar for BBC Radio 2. In October 2007, he announced plans for the "Invincible Donovan University" focusing on Transcendental Meditation, to be near Glasgow or Edinburgh.[49] In October 2007 the DVD The Donovan Concert—Live in LA, filmed at the Kodak Theatre Los Angeles earlier that year, was released in the UK. On 6 October 2009, Donovan was honoured as a BMI Icon at the 2009 annual BMI London Awards.[50] The Icon designation is given to BMI songwriters who have had "a unique and indelible influence on generations of music makers".[51]

2010s–2020s

[edit]In October 2010, Donovan's released the double album Ritual Groove, which he had described as "a soundtrack to a movie not yet made."[52] On 10 May 2021, his 75th birthday, Donovan released the music video for the album's song "I Am the Shaman". David Lynch produced the track and directed the video.[53]

In 2012, he released The Sensual Donovan, recorded in 1971 with John Phillips of The Mamas and the Papas, backed by The Crusaders.[54] In 2013, he recorded the album Shadows of Blue at Treasure Isle Studios in Nashville. The album includes songs he wrote in the 1970s and explores a country style.[55][54]

A tribute album to Donovan, Gazing with Tranquility, was released in October 2015 under nonprofit label Rock the Cause Records to benefit the charity Huntington's Hope.[56] It features covers by The Flaming Lips, Lissie, and Sharon Van Etten.[57]

In 2019, Donovan released Eco-Song, an album of songs with an ecological theme, inspired by Greta Thunberg. He hoped to adapt the album into a rock opera but was unable to due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[58]

To mark the 50th anniversary of Brian Jones's death in 2019, Donovan released a tribute album, Joolz Juke, featuring Jones's grandson (and Donovan's step-grandson), Joolz Jones.[59] In 2021, he released the album Lunarian, dedicated to his wife. The album's song "Still Waters" was recorded decades earlier with Nils Lofgren.[60] Donovan and Lawrence created an animated children's television series, Tales of Aluna, with 26 episodes produced by Australian studio Three's a Company. They had developed the series's story over decades.[59][61]

Donovan released the album Gaelia in December 2022.[62] The album's singles Rock Me and Lover O' Lover featured David Gilmour on guitar.[63] Donovan took 2024 off to prepare for a sixtieth anniversary concert series planned for 2025.[64]

Personal life

[edit]Donovan had a relationship with American model Enid Karl, and they had two children: actor-musician Donovan Leitch in 1967, and actress Ione Skye in 1970.[65] In October of 1970, Donovan married Linda Lawrence.[4] They have two children together, Astrella and Oriole; Oriole had a relationship with Shaun Ryder of the Happy Mondays, and had a daughter, Coco, with whom Donovan has held joint art and photography exhibitions.[66][67][68] Lawrence was the inspiration for "Sunshine Superman".[69]

Donovan is also the adoptive father of Lawrence's and Brian Jones's son, Julian Brian (Jones) Leitch.[13]

In February 2024, Donovan was disqualified from driving for two years and fined €500 for dangerous driving by Skibbereen District Court in Ireland. A charge of being drunk in charge of a vehicle was dismissed, as the court determined it would be unsafe to convict him for that offence. The court heard that the singer was still working and that he supports charitable causes. He has lived in Ireland for thirty years, with no previous convictions.[3]

Donovan, as of February 2024, lives in Castlemagner, Kanturk in County Cork. He suffers from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)[70] and a "restricted lung disease".[3]

Religious beliefs

[edit]Donovan identifies as pagan.[71] Raised Protestant, he left the religion after reading Lao Tzu, Zen and Celtic mythology as a teenager. His personal belief system combines Celtic mythology, Buddhism, and goddess worship.[72] During a 2022 interview with Variety, he said "[E]very other song of mine celebrates the Goddess. She is Mother Nature. And we have been placed in this extraordinary position, almost on the edge of extinction, by this totally, overly male view that every resource, every river, every breeze, every cloud, every metal in the land should be raped and pillaged and sold as a commodity."[73]

Accolades

[edit]In November 2003, the University of Hertfordshire awarded Donovan an honorary Doctor of Letters degree.[74][75] He was nominated by Sara Loveridge (a student at the university who had interviewed and reviewed Donovan for the university paper in 2001–2002); Andrew Morris, Sara's partner and Donovan researcher/writer; and Mac MacLeod.[76]

On 14 April 2012, Donovan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[77][78]

Discography

[edit]- What's Bin Did and What's Bin Hid, a.k.a. Catch the Wind (1965)

- Fairytale (1965)

- Sunshine Superman (1966)

- Mellow Yellow (1967)

- A Gift from a Flower to a Garden (1967), a double album set also released separately as

- Wear Your Love Like Heaven (album 1)

- For Little Ones (album 2)

- The Hurdy Gurdy Man (1968)

- Barabajagal (1969)

- Open Road (1970)

- HMS Donovan (1971)

- Cosmic Wheels (1973)

- Essence to Essence (1973)

- 7-Tease (1974)

- Slow Down World (1976)

- Donovan (1977)

- Neutronica (1980)

- Love Is Only Feeling (1981)

- Lady of the Stars (1984)

- One Night in Time (1993)

- Sutras (1996)

- Pied Piper (2002)

- Sixty Four (2004)

- Brother Sun, Sister Moon (2004)

- Beat Cafe (2004)

- Ritual Groove (2010)

- The Sensual Donovan (2012)

- Shadows of Blue (2013)

- Eco-Song (2019)

- Lunarian (2021)

- Gaelia (2022)

Filmography

[edit]Actor

[edit]- If It's Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium (1969)

- The Pied Piper (1972)

- Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978)

As himself

[edit]- A Boy Called Donovan (1966)

- Dont Look Back (1967)

- "The Deep South", Futurama season 2 episode 12 (2000)

Musical composer

[edit]- Poor Cow (1967)

- Brother Sun, Sister Moon (1972)

- The Pied Piper (1972)

Music and documentary DVD

[edit]- Festival (directed by Murray Lerner, 1967), with footage from the Newport Festival 1963–66. Also with Joan Baez, Bob Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary

- Dont Look Back (documentary film by D. A. Pennebaker, 1967)

- There is an Ocean (1970), a documentary of Donovan and Open Road travelling and performing outdoors on several Greek islands.

- Isle of Wight festival (1970, featuring "Catch the Wind")

- The Secret Policeman's Other Ball (1981, featuring "Catch the Wind", "Universal Soldier", and "Colours")

- Donovan: The Donovan Concert Live in L.A. 21 January 2007

- Sunshine Superman: The Journey of Donovan (2008, documentary directed by Hannes Rossacher)

- I Am The Shaman (2021, single produced and directed by David Lynch)

Literary works

[edit]- Leitch, Donovan, The Hurdy Gurdy Man, Century, an imprint of Random House, London, 2005 (published in the US as The Autobiography of Donovan: The Hurdy Gurdy Man), St. Martin's Press, New York, 2005; ISBN 0-312-35252-2

References

[edit]- ^ "Gold & Platinum". Riaa.com.

- ^ "McCartney Interview 20 November 1968". Dmbeatles.com. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "Musician Donovan (77) fined €500 and given road ban for dangerous driving". The Irish Times. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ a b Andy Gregory (2002). The International Who's Who in Popular Music 2002 (4 ed.). Europa Publications. p. 141. ISBN 978-1857431612.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Artist Biography [Donovan]". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ "How Donovan and Coco, his granddaughter, caught their wind". Independent.ie. 3 April 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Janet Attwood and Christine Comaford. "Cover Story Article". Healthywealthynwise.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Prager, Felice. "The Hurdy Gurdy Man of the Psychedelic Sixties – Donovan Leitch". Rewind the Fifties. loti.com. Archived from the original on 9 January 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Donovan, Leitch (2006). The Hurdy Gurdy Man. Arrow. ISBN 0-09-948703-9.

- ^ Dixon, Kevin (17 July 2010). "Torquay's other history: the inspiration of folk superstars Donovan and Mac Macleod". Peoplesrepublicofsouthdevon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "reviews". Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 48 – The British are Coming! The British are Coming!: With an emphasis on Donovan, the Bee Gees and the Who. [Part 5]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- ^ a b Brian Jones: The Making of the Rolling Stones and Sympathy for the Devil: The Birth of the Rolling Stones by Paul Trynka – and the Death of Brian Jones by Paul Trynka

- ^ Rolling Stones off The Record", Mark Paytress, p. 90

- ^ "Melody Maker". Sabotage.demon.co.uk. 5 May 1965. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Marcus, Greil (2011), Greil Marcus interviews D.A. Pennebaker about filming Bob Dylan, New Video's Docurama Films

- ^ Anon (23 May 2001). "Donovan remembers Dylan". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ^ "Allen Klein". The Beatles Bible. 25 March 2008.

- ^ a b c d Anon. "Donovan". www.classicbands.com. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ^ "Guitarist Big Jim Sullivan dies". BBC News. 3 October 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Jack Bruce Discography – 1963–2010". www.jackbruce.com. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Donovan With Danny Thompson – Discography". www.45cat.com. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Season of the Witch". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Interview: Donovan". Hit-channel.com. 20 June 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd. p. 204. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- ^ Donovan; Leitch, Donovan (2006). The Hurdy Gurdy Man. Arrow. ISBN 9780099487036. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ "Follow the ever-changing ballad of Shawn Phillips". 25 July 2012.

- ^ Donovan, Donovan in Concert, released on Atlantic July 1968, re-issued on BGO February 2002. ASIN B0000011LU.

- ^ Greenfield, Robert (17 June 2009). A Day in the Life:One Family, the Beautiful People, and the End of the Sixties. Hachette Books. ISBN 9780786748006. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ Hitchens, Peter (2012). The War We Never Fought: The British Establishment's Surrender to Drugs. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-4411-7331-7 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Shea, Stuart; Rodriguez, Robert (2007). Fab Four FAQ: Everything Left to Know About the Beatles ... and More!. New York City: Hal Leonard. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4234-2138-2 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Jones, Steve (2002). Pop Music and the Press. Temple University Press. ISBN 9781566399661. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ "The Season of "Season of the Witch"". www.newyorker.com. 16 May 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ Carpenter, John (9–23 November 1967). "Donovan: The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone. Vol. 1, no. 1, 2.

- ^ "Paul McCartney Interview: Promoting the White Album (20 November 1968)". Dmbeatles.com. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "Rolling Stone – Donovan on teaching guitar technique to the Beatles". You Tube. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Liner notes, Troubadour: The Definitive Collection 1964–1976, Sony Music Entertainment, 1992. ("Hurdy Gurdy Man" recording in London, England, 1968, crediting Donovan on vocal, acoustic guitar and tambura, Allan Holdsworth and Jimmy Page on electric guitars, John Paul Jones on bass, John Bonham and "Clem Clatini" (a misspelling of Clem Cattini) on drums, produced by Most, arrangement by John Paul Jones, Epic LP BN 25420, Epic single 5-10345.)

- ^ DeCurtis, A., "Donovan's Calling", essay released in liner notes of Try for the Sun: The Journey of Donovan 2005 limited-edition boxed set compilation by Sony BMG Music Entertainment Legacy Recordings.

- ^ a b Leitch, Donovan, The Hurdy Gurdy Man, Century, an imprint of Random House, London, 2005 (published in the U.S. as The Autobiography of Donovan: The Hurdy Gurdy Man, pp. 218–19 St. Martin's Press, New York, 2005; ISBN 0-312-35252-2).

- ^ "Donovan". officialcharts.com. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ "Lochbay Boathouse, Stein – Self Catering". www.visitscotland.com. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ "The Beatles in Scotland: George Harrison's story". Daily Record. 2 November 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d Lorne Murdoch, liner notes to Barabajagal expanded CD reissue (EMI, 2005)

- ^ "The Post-Donovan High". Beat Instrumental & International Recording. 1971.

- ^ Windy Daze (CD Liner). Cherry Red Records Ltd. 2021.

- ^ Everett, Walter (31 March 1999). The Beatles As Musicians:Revolver through the Anthology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199880935. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ "David Lynch Weekend draws crowds to Maharishi University of Management". Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ Rajan, Amol (24 October 2007). "Bring peace to schools by meditation, say Lynch and Donovan". The Independent. London. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Invincible Donovan University". The Journal. Edinburgh. 5 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011.

- ^ "BMI Icon Donovan Honored in London". Billboard. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson to be Honored as Icon at 57th Annual BMI Country Awards". bmi.com. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ "Donovan: The 'Sunshine Superman,' Part II". Goldmine. 15 October 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (10 May 2021). "Donovan Taps David Lynch to Direct New Video for 2010 Song 'I Am the Shaman'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ a b Kozinn, Allan (10 June 2014). "A Genre Dabbler Gets His Accolades". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Doyle, Patrick (17 July 2013). "Donovan Returns to Nashville on New LP 'Shadows of Blue'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Moon, Tom (7 October 2015). "Review: 'Gazing With Tranquility: A Tribute To Donovan'". NPR. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Spanos, Brittany (23 July 2015). "Flaming Lips, Sharon Van Etten to Cover Donovan". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Williams, Zoe (9 April 2020). "Donovan: 'Can you believe the Beatles and I were paying 96% tax?'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ a b Enos, Morgan (1 June 2021). "Donovan On His New Single "I Am The Shaman," His Upcoming Animated Series & The Role Of The Shaman In Everyday Life". Grammy Awards. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Young, Amy (15 March 2021). "'60s Folk Icon Donovan Releases Unheard Songs Featuring Legendary Guitarist Nils Lofgren". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Gaydos, Steven (14 May 2021). "Singer-Songwriter Donovan Takes Climate Message to Animation". Variety. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Gaydos, Steven (2 December 2022). "Donovan Dives Into the Ancient Roots of His New Album, 'Gaelia,' and Why He Still Believes Music Can Save the World". Variety. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Willman, Chris (25 November 2022). "Donovan Unveils Historic David Gilmour Collaboration, 'Rock Me,' With 'Gaelia' Album Set to Follow (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (19 March 2024). "Donovan Talks Celebrating His Soundtrack for Franco Zeffirelli's 'Brother Sun, Sister Moon' With Italy's President and Franciscan Monks (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ "Flower Child Looks To Bloom Again: Donovan, The Trippy Troubadour Behind Such Generation- Defining Hits As Mellow Yellow and Sunshine Superman, Is Back At 50 With A New Album". The Philadelphia Inquirer. '60s Archives. 30 November 2005. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ "How Donovan and Coco, his granddaughter, caught their wind". 3 April 2017.

- ^ Leitch, Donovan (2007). The Autobiography of Donovan: The Hurdy Gurdy Man. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 144. ISBN 978-0312364342.

- ^ "Page Redirection". Astrella-celeste.com. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Simpson, Dave (2 May 2016). "How we made: Donovan's Sunshine Superman". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)". nhs.uk. 20 October 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Linda Serck (3 August 2005). "Donovan Interview". MusicOMH. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ Kira L. Billik (29 March 1997). "Minstrel Donovan weaves magic with 'Sutras'". The Standard-Times. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ Steven Gaydos (2 December 2022). "Donovan Dives Into the Ancient Roots of His New Album, 'Gaelia,' and Why He Still Believes Music Can Save the World". Variety. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Gracious me, Sanjeev's a doctor!". Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "University to honour Donovan and TV comedian". 12 November 2003. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "Donovan awards and honours". Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "2012 inductees". Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "Donovan on His Acceptance into the Hall of Fame". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Donovan at IMDb

- Donovan interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1970)

- "Donovan". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

- Donovan

- 1946 births

- Living people

- 20th-century Buddhists

- 21st-century Buddhists

- 20th-century Scottish male singers

- 21st-century Scottish male singers

- British Invasion artists

- British folk rock musicians

- British folk-pop singers

- British harmonica players

- Dawn Records artists

- Epic Records artists

- Fingerstyle guitarists

- Hickory Records artists

- Marble Arch Records artists

- Musicians from Glasgow

- People from Hatfield, Hertfordshire

- People from Maryhill

- Psychedelic folk musicians

- Psychedelic rock musicians

- Pye Records artists

- Rak Records artists

- 21st-century Scottish autobiographers

- Scottish buskers

- Scottish folk singers

- Scottish male singer-songwriters

- Scottish singer-songwriters

- Scottish people of Irish descent

- Scottish pop singers

- Scottish record producers

- Scottish rock singers

- Transcendental Meditation exponents

- Scottish people with disabilities

- Singers with disabilities

- Converts to Buddhism from Protestantism

- Scottish Buddhists

- Converts to pagan religions from Protestantism

- Scottish modern pagans