Draft:Argentine territorial nationalism

| An editor has marked this as a promising draft and requests that, should it go unedited for six months, G13 deletion be postponed, either by making a dummy/minor edit to the page, or by improving and submitting it for review. Last edited by Citation bot (talk | contribs) 4 days ago. (Update) |

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Citation bot (talk | contribs) 4 days ago. (Update) |

Argentine territorial nationalism is a phenomenon of Argentine society based on the contrast between a perception of past territorial losses and the reality of huge territorial gains. It therefore lies within the realm of political psychology, making it different from political nationalism and economic nationalism. The political groups that are prone to these different forms of nationalism do not coincide, although they sometimes overlap, making them difficult to define succinctly.[1] Territorial nationalism is prevalent in many states in Latin America but is particularly notable in Argentina where it has significantly and detrimentally affected that country's relations with its neighbours, especially Chile and the United Kingdom.[2] The reasons for this phenomenon are rooted in history.[3] It is widespread in Argentine thinking,[4] where Argentines are taught in school that the country comprises three interlinked parts: mainland Argentina, insular Argentina and Antarctic Argentina. Accepting anything less is seen as a betrayal of the fatherland.[5][6]

Historical context and causes of the phenomenon

[edit]The background to the phenomenon lies in medieval Christian history and in the time when large areas of the American continent were part of the Spanish Empire.[7]

Inter Caetera et uti possidetis juris

[edit]

A central premise to all Argentina's claims to the South Atlantic islands and to part of Antarctica is that Argentina inherited Spain’s sovereign title to those lands at independence in 1816. Spain’s title, the line goes, had been decreed by Pope Alexander VI in the 1493 bull, Inter Caetera,[8] one of three edicts that year which are collectively known as the Bulls of Donation. These were superseded the following year, with only minor amendments and with papal approval, by the temporal 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas between Spain and Portugal.[9] According to many Latin American scholars, a series of later treaties with other European powers confirmed Spain’s title.[citation needed] The bull gave all non-Christian land, both known and unknown, west of a latitudinal divide in the Atlantic Ocean, to the Crown of Castile,[10][11] with land to the east of the divide going to Portugal. The land in the Spanish sphere included North and South America, part of Antarctica and numerous islands. Argentina maintains that papal bulls were accepted as valid legal documents by other west European countries at that pre-reformation time when all west European monarchies were Roman Catholic: the pope's authority as God's representative on Earth was, therefore, unchallenged. As a result, according to Argentina, because title was already accepted as being with Spain, the British claims in the region are all invalid because they post-date the Spanish title. This principle in international law is known as uti possidetis juris, the name of which is the same as a different principle used in Roman law.[12] An arbiter's dictum on the legal merits of this argument was given in 1922 in relation to a Colombia-Venezuela boundary dispute. It said:

- "When the Spanish colonies of Central and South America proclaimed their independence in the second decade of the Nineteenth Century, they adopted a principle of Constitutional and International Law to which they gave the name of uti possidetis juris of 1810. The principle laid down the rule that the boundaries of the newly established republics would be the frontiers of the Spanish provinces which they were succeeding. This general principle offered the advantage of establishing the absolute rule that in law no territory of old Spanish America was without an owner. To be sure, there were many regions that had not been occupied by the Spaniards and many regions that were unexplored or inhabited by uncivilised natives, but these sections were regarded as belonging in law to the respective republics that had succeeded the Spanish provinces to which these lands were connected by virtue of old Royal decrees of the Spanish mother country. These territories, although not occupied in fact, were by common agreement considered as being occupied in law by the new republics from the very beginning. Encroachments and ill-timed efforts at colonisation beyond the frontiers, as well as occupations in fact, became invalid and ineffective in law. The principle also had the advantage, it was hoped, of doing away with boundary disputes between the new States. Finally it put an end to the designs of the colonising States of Europe against lands which otherwise they could have sought to proclaim as res nullius."[a][13]

In addition to these comments on the principal's questionable legal merits, the meaning and effect of inter caetera is also open to different interpretations. A closer examination of the bull casts doubt on the straightforward, commonly held view which holds that Alexander, at the stroke of his quill, dividing the world between two small Catholic kingdoms. Viewed more thoroughly in the context of the time in which it was written, that conclusion is wrong.[14] There are two important objections.

First, what must be taken into account is that the bull was the culmination of 250 years of papal legal thinking and that many other related bulls had been, and were still being, written. These were part of attempts to define the nature of Christianity's relationship with infidels and the responsibility the pope had to protect infidels, by converting them to Christianity - through which they would then find salvation.[15] In the context of medieval Church history, the infidels in question were the non-Christian Jews and Saracens. The indigenous peoples of the new lands being discovered were treated within that already established thinking, not as something uniquely different.[16]

Second, and again viewing the bull in the context of its day, instead of sovereignty, the bull granted an infeudation title, a form of land transfer common at the time when the concept of absolute sovereignty was still developing. (The concept of sovereignty as it is know today is generally thought to have been established in 1648 at the Peace of Westphalia). Infeudation title was a precursor to the later system of ownership in trust by which a person can keep control of and benefit from an asset without legally owning it. In this case the owner of the land (the feoffor), namely God, would, through the pope, divulge to the Castilian monarch, (the feoffee), rights to use and reap from the new lands in return for a consideration - spreading the Word of God to convert the indigenous peoples, thereby saving them from eternal damnation in hell.[17][18]

From this contemporary perspective, the bull gave possession rights, not sovereignty, to Castile and Portugal, for the purpose of spreading Christianity, but only in land that was not already in the possession of other Christian powers (because they would be spreading the Word). Incorporated in the bull was the corresponding obligation on Castile and Portugal first to exercise their rights of possession by establishing their presence, an early example of an incohate titlet within the still developing discovery doctrine. This requirements to proselytize and occupy accounts for the numerous missionary stations set up along the South American coastline and further inland.[19]...effectivite and encohate.[20]

1/ Argentina argues that in the 16th century papal bulls were accepted as valid legal documents by all other relevant European states whose subsequent actions have by and large confirmed that. This means, according to Argentina, there is no need to become embroiled in the machinations of later claims by other states, because Spain's title, that passed to Argentina, had not been in doubt and was not affected by later developments in the way European states acquired overseas territories. It says the 1493 bull (and its slight amendment by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas) is still valid. As a result, because title was already with Spain, Argentina say the British claims to Antarctica, the Falklands and various islands are all invalid because they post-date the Spanish title, which passed to Argentina in 1816 under uti possidetis juris.[21] The meaning and effect of inter caetera is open to different interpretations, especially when taken in context with the time it was written. The Spanish claim, that it granted sovereignty to Spain over half the world is only one, extreme, interpretation that other interpretations dispute. These include, for example, that the bull is it granted an infeudation, not sovereignty;[22] or that in any case, it would only have been binding between Spain and Portugal, based on res inter alios acta, aliis nec nocet nec prodest.[23]

5..Not accepted by others. France and England also made claims to territories inhabited by non-Christians based on first discovery, but disputed the notion that papal bulls, or discovery by itself, could provide title over lands. In 1541, French plans to establish colonies in Canada drew protests from Spain. In response, France effectively repudiated the papal bulls and claims based on discovery without possession, the French king stating that "Popes hold spiritual jurisdiction, and it does not lie with them to distribute land amongst kings" and that "passing by and discovering with the eye was not taking possession."[12] Discovery doctrine[24]

History of expansion southwards

[edit]

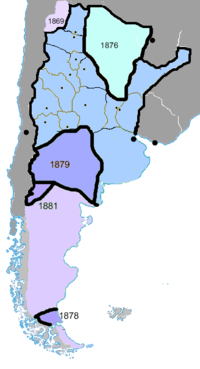

During the colonial period, the Spanish Crown failed to create distinct administrative boundaries in Patagonia and the adjacent areas, if any at all. Later, this failure hindered Argentina and Chile in their efforts to establish clear uncontested titles based on uti possidetis iures.[25] After independence in the early 19th century, neither country took much interest in expanding south into Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. Fiercely independent native Indians on both sides of the Andes proved to be a formidable obstacle; and both governments had more pressing issues to deal with: Chile, for example, was competing with Peru for dominance in the Pacific trade routes which at that time were usually overland across Panama rather around Cape Horn, a more treacherous route.[26]

In 1840, the British company "Pacific Steamship Navigation Company" sent its first two steamers, named "Chile" and "Peru", from England to Valparaiso. They passed through the Strait of Magellan rather than rounding Cape Horn. This single act suddenly turned the Strait into an important international waterway that could be vital for Chilean trade because it created a simple and safe alternative to the Panama route: (the Panama Canal wasn't opened until 1888). However, Britain and France had also seen the potential of controlling the strait, an area that had not then been settled by Chile or Argentina. To pre-empt European moves, in 1843 Chile decided to occupy the Strait by founding the penal colony of Fort Bulnes on the Brunswick Peninsula, the most southerly part of mainland South America. The settlement was on the north shore of the Magellan Strait, with Tierra del Fuego on the opposite bank: it was moved to a nearby site along the shoreline in 1848 and renamed Punta Arenas. The Chilean government, having occupied the eastern portion of the strait, then specifically disclaimed any sovereignty rights to the eastern portion. It made this precipitously abnegation in consideration of any moves by the European powers, not to pre-empt any claim by Argentina.[27] Despite being excluded in Chile's 1833 constitution, from 1853, Chile changed its position on owning Patagonia?????. It did this in stages culminating in a claim to most of Patagonia up to the mouth of the Rio Negro on the Atlantic coast and to the Diamante river in the cordesella. Despite its ambitious claim to Patagonia, Chile did not show any active signs of effective occupation there beyond its penal colony until the 1870s when sheep transportation with the Falklands began,[28] Inconclusive negotiations followed from 1853 which brought both sides close to war in 1878.

In contrast with the lack of action in the south, the eastern slopes and valleys of the Andes as far north as the latitude of Buenos Aires were actively settled from the Chilean side by sheep farmers and others. A steady flow of settlers progressively moved south along the eastern slopes of the Andes to the Neuquen Valley. South from there was the Pre-Andean Depression which provided the only available land route south to the Magellan Strait from either Chile or from Buenos Aires.[29] This important route was, however, blocked by the Indians by Araucanian tribes south of the Bio-Bio river.[30]. (There was at the time no usable route on the Atlantic side.)

Argentina's effective southern boundary until the 1870s was only around 100 miles from the Rio de la Plata, with its peripheries being occupied by large cattle ranches. South of there lay the Pampas which were controlled by belligerent Indians who, on horseback, continuously ravaged the border and stole vast herds of cattle, taking them over the mountains in a lucrative trade with Chile. At the time, Chile could, if it so chose, have used the Indians as an auxiliary force to advance its army onto the Pampas through the Cordesilla and along the Rio Negro. Here, it was believed, would be where a war would take place to secure any claim to Patagonia, not in Patagonia itself.[31] Chile's superior navy would have assisted in taking control of the Atlantic coast, an area that had been neglected by Argentina which had taken only minimal steps to enforce its claim there, such as settlements in the Chubut Valley in 1865 and xxxx.[32]

In 1879, Chile became involved in the War of the Pacific with Peru and Bolivia and a fortnight later Argentina began the final campaign of Conquest of the Desert which eventually led to Argentina's taking effective control of the Pampas, the eastern slopes of the Andes and Patagonia. Conversely, Argentina benefited from Chile's failure.[33] By not following through on its claim to Patagonia when it could have done so successfully, Chile missed its rendezvous with destiny.[31] The boundaries as seen today were formalised, after considerable jockeying for position, in the 1881 Boundary Treaty. Chile got the entire Magellon Strait but agreed it would be de-militarised, while Argentina got all of Patagonia, denied Chile an Atlantic coastline and avoided a potential enemy on it southern flank.[34]

Title deeds and mendacious manipulation

[edit]{ill|Article title|language code}}

English article title = template

Revisionismo histórico en Argentina

es:Revisionismo histórico en Argentina

During the expansion south into Patagonia, an intense debate took place between Chileans and Argentinians over title deeds. The debate was led on the Chilean side by Miguel Luis Amunátegui and on the Argentine side by Vicente G. Quisada. Each side was trying to show that title deeds to vast areas of land, that were created during the colonial period by Spain and given to one of the then colonial jurisdictions, had been inherited by what was assumed to be the successor state of that particular jurisdiction, either Chile or Argentina.[35][36] To do this colonial documents were used to demonstrate the supposed intention of the Spanish Crown in an agreement it signed in 1810. That agreement, the 1810 uti possidetis juris...

In 1853, Titles of the Republic of Chile to Sovereignty and Dominion of the Extreme South of the American Continent, was published by the Chilean historian, Miguel Luis Amunátegui. It said Chile had a valid claim to all Patagonia up to the Rio Negro on the Atlantic side. It received a firm rebuttal from Argentina and stormy ongoing exchanges followed, bringing both sides close to war in 1878.[37]

In 1875, following a trip to Europe, Quisada published his controversial book, "La Patagonia y las tierras australes del continente Americano", which made the claim, against that of Chile, that Argentina was the exclusive heir to Patagonia. In 1877 he was appointed minister of government for the province of Buenos Aires and in 1878 was elected deputy to the National Congress. In 1881 he published "El vierreinato del Río de la Plata, 1776–1819", again motivated by the border disputes with Chile. In this book he forcefully developed the legend of the Viceroyalty of La Plata being a great nation conceived by Charles III of Spain and forever lost by the actions of incompetent Argentine governments. This fed into a school of liberal and revisionist thinking in Argentina that nurtured an early form of territorial nationalism.[38]not rss?

Widespread scholarly misconception that there were huge territorial losses to Chile in the south and territorial losses elsewhere

[edit]

There is a perception that Patagonia and the far south of South America were part of the Viceroyalty of the River Plate. This perception is so widespread, even within scholarly circles, that many Argentine claims about its history have been accepted and gone unchallenged.[39] The far South of the South American continent was claimed by Spain but was not settled until the late 19th century: until then it had been Indian territory over which Spain exercised no effective control. This misconception of the extent of Spanish authority is shared to a lesser extent by Chile. Having the advantage of becoming an homogenised state earlier than Argentina, which suffered from Balkanisation and civil wars, Chile first established a military outpost, and hence control, in the region in 1843, which soon after became the settlement of Punta Arenas.[39] One reason why successive central governments in Buanos Airies began spreading fake news about the extent of the country's territorial gains and losses was that they wanted to instill into new immigrants from Europe a shared sense of their new county's history and geography. The 'lost' territories include the Falklands Islands in which the British established a permanent settlement in the 1830s: before then an assortment of communities had been stationed there: British, French, Spanish and Argentine.[40]

This belief is backed by many academics who use inter caesera to make the erroneous assumption that Spain possessed Patagonia and all land down to the South Pole, and it follows, according to uti possidetis juris, that this land became the property of the new Latin American republics at independence.[41][25][42] They maintain that even without having a presence in those southern lands, Spain always had at least animus occupandi, an intention to occupy, something which is illustrated by the Capitulation (treaty) capitulacion granted to Pedro Sánchez de la Hoz in 1534. In the 1860s, this fallacious nature of this assumption, shared to a lesser extent by Chile,[43] was demonstrated by the quixotic French lawyer, Orélie-Antoine de Tounens, who travelled south of the Biobío River, a traditional boundary to Chile's expansion into uncolonised land to the south. He got the consent of the fiercely independent Mapuche people to make himself king of all the land down to Cape Horn, including Patagonia. He was saved from execution for his troubles due only to his perceived insanity.[44] Even as late as the 1881 border treaty between Chile and Argentina, Patagonia was still decades away from being fully explored and settled.[45]

Non-recognition of territorial gain to offset losses

[edit]There is a perception in Argentina that during the 19th century, Chile expanded south of the River Bio-Bio into Patagonia at Argentina's expense. The reality is that both countries expanded southwards into Indian territory.[46] Chile's had the ability to enforce its claim to Patagonia in the 1860s but through a combination of circumstances in failed to do so. This fortuitous failure was to Argentina's advantage. Following the 1881 treaty, the area of land gains in the Patagonia and the far south was greater than the land in the north that passed from the vice-royalty of the river plate to other newly created South American states.

Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina,had also been the capital of the Viceroyalty of the River Plate

[edit]This fact has created the impression in Argentina that if an area was once governed from Buenos Aires, as it was as part of the viceroyalty, then it should still be governed from Buenos Aires, even if the administering entity has changed, as it has to Argentina. It is assumed therefore, that if that is not the case, and land once in the viveroyalty is now administered from another city, then there has been a territorial loss by Argentina. That means there is a failure to accept that the Viceroyalty was the precursor, at least in part, to other modern states as well as to Argentina, such as Bolivia, Uruguay and Paraguay, resulting in those countries therefore containing land which Argentina has lost.[39] This misconception is compounded by Spain's late recognition of the independence of the states that emerged from its Viceroyalties. From the Spanish position, the new national boundaries did not exist.[47][6]: 316 [48] Full recognition of Argentina by Spain, for example, did not take place until 1863.[49] One reason, among many, for this late recognition was the internesine struggle within Argentina at the time between Federalists and Unitarists, which prevented the country from clearly defining its own borders.

Argentine relations with Britain plunge from willing deference, through nationalist sniping, to war: 1850-1982

[edit]A basic overview of the wider history of Anglo-Argentine relations is necessary to put into context Argentina's nationalist territorial claims in Antarctica and on South Atlantic islands.

Close mutually beneficial economic ties with the United Kingdom, 1850-1929

[edit]

Britain and Argentina began a close relationship in the latter half of the 19th century. The priority of successive Buenos Aires governments was to bring in immigrants to the sparsely populated country (1 million in 1860).[50] For this to happen, infrastructure was needed, such as a national train network, and in this regard British companies were able to help.[51] Argentina benefited from its agricultural products having access into markets within the British Empire while in return British capital and technology contributed to Argentina's expansion and rapidly developing economy. This co-operation peaked in 1933 with the signing of the Rosa-Runcimann Agreement in which Argentina received continued access to imperial markets in exchange for further preferential arrangements for British businesses. Despite there being advantages for Argentina, the 1933 agreement was weighted in Britain's favour. This long-standing relationship has been described by Adrian Howkins as akin to an informal British empire in Argentina, in which Britain asserted its authority with its greater wealth and superior science. This economic connection resulted in British officials often calling Argentina the sixth Dominion.[52] By extension, British informal authority reached beyond Argentina to the formal, or actual, parts of the empire, namely the Falklands and the Dependences, where Argentina's territorial claims were in abeyance.[53] Patriotic wealthy Argentinians, especially the land owning elite, were happy to see nationalist territorial expansion at the expense of Chile in Patagonia, but they mellowed their claims to the 'stolen' Malvinas, in order not to upset the apple-cart with Britain whose position in the Falkland Islands went largely unchallenged.[54] A small but influential British expat community also prospered from this cozy set-up.[55]

The tide turns - efficacious interaction gives way to nationalist bickering and sobering diplomacy: 1930-1946

[edit]Following a coup in 1930, a new Concordancia government led by the wealthy elite came to power at a time when Argentina faced losing its primary export market. The Great Depression was taking hold and Britain was retreating into protectionism. In 1933, the concessionary Roca-Runciman Treaty was signed as the government tried to hang on to the imperial markets.[56][57] Nationalists, who were unhappy with the Concordancia government anyway, were energised by what they saw as a sell-out to the British. To placate this nationalist sentiment the government took a stronger line in asserting Argentina's claims to the Falklands and the Dependencies. For example, in 1939, a Commission was established to investigate Argentina's territorial claims in Antarctica.[58]

At the outbreak of war with Germany in 1939, Britain had to keep open the sea lanes for critical food imports. The South America link was vital: for example, during the war Britain was to receive 40% of its beef from Argentina. The unprotected Falklands and Dependencies offered ideal bases for German submarines and raiders, giving London an additional worry and another reason not to stir up nationalist sentiment. Argentina continued the supply of food while Britain strengthened its presence in the region, despite the risk of riling the nationalists. A 300-strong garrison made up partly from the British community in Argentina did not help the delicate balancing act being played out by both sides. In December 1941, a new element was added to the mix when Japan entered the war. In January 1942, at a pan-American meeting to discuss the Japanese threat, the nationalist leaning Argentine acting-president conspired to further the country's territorial ambitions by proposing that Argentina be given responsibility for defending the Falklands. British pressure on the Americans meant the idea came to naught but not before a British diplomat opined: "These blackmail tactics are what might have been expected of the Government of acting President Castillo and Sr. Ruíz Guiñazu [Foreign Minister]. Either way they have something to gain. If they do not get the Falklands they have an admirable excuse for staying out of the war; if they do get them they at once become national heroes instead of being disliked and despised by 90% of the Argentine public."[59] Meanwhile, in early 1942, nationalist jibes continued and Argentina sent expeditions to the Antarctic Peninsula. The British ambassador in Buenos Aires ignored instructions from London and refused to protest, judging it better not to fan the nationalist flames. In August 1942, with the threat of a Japanese invasion in mind and at Churchill's intervention, Britain sent 2,000 troops to the Falklands, which also had the effect of ending any threat from Argentina. (It later emerged that a plan to invade the Falklands had been drawn up in 1941 by an Argentine naval officer.)[60] In the following Antarctic summer, HMS Carnarvon Castle was dispatched to counter a possible threat to the Dependencies from another Argentine expedition aboard the transport ship ARA Primero de Mayo.[61] While there, the British removed some Argentine sovereignty markers left behind. Later in 1943, Britain took the further step of sending a secret military expedition, Operation Tabarin, to set up permanent bases on the Antarctic peninsula.[62] After the war in 1947, Juan Peron became president.

Peronism and beyond: post-1947

[edit]

Juan Peron planned to shape a new Argentina and a new Argentine citizen and in so-doing to transform all aspects of Argentine society.[63] He promised to liberate the masses from the injustices caused by earlier oligarchic regimes.[64] To do this he employed the peronista technique of reaching out to the xenophobia within the masses. The education system was an important tool used to create this 'new Argentina' by creating a new national consciousness in the minds of the young.[63] In the 1950s, slogans appeared on buildings such as "Englishmen, give us back the Malvinas!" and after Peron left office in 1955 such slogans continued to appear with monotonous regularity.[65] By 1950, Argentina's reliance on Britain had largely disappeared which consequently removed Britain's worry of offending Argentina by taking a tougher stance on the Falklands and the Dependencies. Argentine military assertion of its territorial claims were met by prompt responses from London, at Hope Bay on the Antarctic Peninsula in 1952 and Deception Island in the South Shetland Islands in 1953. However, Argentina milked the incidents for their propaganda value. Calls for the return of the Falklands continued in the 1960s, after Peron had been removed in a coup, with the military government that took over continued the nationalist territorial rhetoric against the British possessions.[66] Belief in the claims was one of the few things that united all sectors of the Argentine society. After the Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1959, suspending claims in Antarctica and nearby islands, Argentina continued its anti-British stance, relying more on the United Nations as an outlet for its posturings. In December 1965, the UN adopted resolution 2065, which called on Argentina and the UK to engage in talks to resolve their differences. In January 1966, the Argentine government set up the Instituto y museo nacional de las Islas Malvinas y Adyacencias to 'stimulate the national consciousness' for the return of the Falklands. A specialist library together with nationwide propaganda talks and films were arranged.[67] In September 1966, a group of young Argentines, members of the Moviemento Nueva Argentina flew to the Falklands to staged a mock seizure of power. The stunt attracted widespread popular support in Argentina, it was praised by pro-Peronist groups and the protesters became national heroes overnight.[65][68] The decades old lingering disquiet at the perceived loss of the Falklands in 1833 had been re-energised by the post-war nationalist policies of the Peronist movement. After the UN declaration, drawn out discussions began between London and Buenos Aires but without success. On 2 April 1982, under another military government, Argentina invaded the Falklands. Margaret Thatcher, the embattled British prime minister, listened to Admiral Sir Henry Leach and 74 days later Argentine forces surrendered and were ignominiously taken home.[69][70] Despite that, Argentina's nationalist agitprop continued unabated.

Case studies in Argentina's international relations

[edit]Overview

[edit]The reasons behind each claim are case specific and sometimes one reason is used to back more than one claim. This results in some claims intermingling, thereby being mutually dependent. Another factor that can cause ambiguity is that some texts promoting the Argentine position are pleonastic, lack precision or both. For example, the grounds for Argentina's various sovereignty claims are ill-defined and nebulous, as in its 2023 "claim to the Argentine Antarctic Sector [being] based on solid historical, geographical, geological and legal grounds."[71] There is no more specific detail with this statement. However, beneath the verbosity and fuliginous language it is possible to extract some legal principles in international law that are regularly used to support the different claims.

- Disputes with other Latin American states arise predominantly from border ambiguity at the time when much of South America was part of the Spanish empire. Many borders within the empire, used then for regional and administrative separation, were not clearly defined or simply did not exist. Later disputes have, therefore, dealt with the uti possidetis iuris principle, by which newly independent states take over the already established borders of the predecessor state.[72][73]

- Embedded in disputes with the United Kingdom is the discovery doctrine which Buenos Aires says confirms Spain's, and later Argentina's, sovereignty over various territories. For Argentina, its sovereignty based on discovery can be traced back to Inter Caetera, discussed earlier.[74] The discovery doctrine includes effectivités, or effective occupation.[75][76]

Argentina's claim to the South Atlantic islands and Antarctica,[77] stems from the Bull Inter Caetera issued by Pope Alexander VI in 1493. The Bull divided the earth into two parts, east and west of a stated longitute with the latitudinal limits not being defined more precisely than the top and bottom of the world. Either part was given to the Castilian (shortly to be Spanish) and Portugese Crowns respecively). This Papal Bull argument, which fell from use in post Reformation Europe, is disputed by most other countries for many reasons. For the European powers, ownership by discovery[78] gained favour, giving way in the 19th century to legally stronger bases for sovereignty claims. Ownership by effective possession (such as was included in the 1888 Berlin Treaty to bring some necessary order to the rapidly developing Scramble for Africa became the new benchmark, which was reinforced and developed by international courts. Berlin treaty 1888[79][80]

In practice, discovery refers to discovery and utilisation by Europeans, despite many newly discovered lands already being occupied by indigenous peoples. Their rights were recognised but given little weight until the 20th century. According to Oppenheim: "The only territory which can be the object of occupation is that which does not already belong to another state, whether it is uninhabited, or inhabited by persons whose community is not considered to be a state; for individuals may live on as territory without forming themselves into a state proper exercising sovereignty over such territory."[81] This belief meant that land occupied by many indigenous people who did not cultivate the land was treated as terra nulius.Effectivités has been more clearly defined in international law through interstate treaties and court rulings. These include the 1885 Berlin Treaty which used the principle as the signatory states attempted to instil some order into the rapidly escalating Scramble for Africa. The Johnson v. McIntosh (1823) in the United States and the 1928 Permanent Court of Arbitration decision in the Island of Palmas case both confirm that discovery alone only establishes an inchoate title, giving the discoverer the right to perfect it into a full title within a reasonable time by effectively occupying the territory.[82], as does malaysia-indonesia-effectivites.... sources?--Claims with the United Kingdom are less clear-cut and raise other issues. At times, Argentina uses territorial contiguity as a basis for a claim. This means the claimed land has a geographical connection with Argentina and should therefore, it is claimed, naturally be part of Argentina, such as the Falkland Islands' being on the South American continental shelf. United Nations declarations regarding de-colonisation have also emerged post World War Two as further grounds for Argentine claims, although these declarations are a double edged sword because they can also be used against Argentina. To varying degrees, all grounds for Argentina's claims are inherently weak.

- The creation of the United Nations in 1947 added another dimension to the issue of European states having sovereignty over vast areas of land and over native peoples around the world. In an effort to add weight to its claim to the Falklands, and following the 1960 United Nations' Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples (Resolution 1415), Argentina lodged a resolution which was adopted in 1965 as United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2065. This called on both sides to work together to resolve their sovereignty dispute.[83][84] Demands by Argentina that Britain ends its colonial occupation of the Falklands does however a double edged sword because the islands were uninhabited prior to European settlement, making indigenous population those there now, who overwhelmingly wants to stay British, a fact steadfastly asserted by Britain.[85] Determining whether any of the various settler groups before 1833 could be considered as the indigenous population is fraught with problems, although Argentine advocates insist the xxxx settlement is the one to consider, which it claims, was force-ably removed by Britain.[86]

- An obstacle to Argentina's discovery based claim is concept of prescription, whereby a claim can be lost if another state acts as if it had sovereignty without being challenged for a lengthy undefined period of time.[87]

- A theory advanced to justify Argentina's appropriation of land without effective occupation is the theory of contiguity, also known by its pseudonym, propinquity.[88] This says the sovereignty acquired over a part of a geographical unit extends to all parts of the same unit. For example, the sovereignty acquired along coast would create sovereignty over all land behind that coast (the "hinterland") up to a natural border.[89] Similarly, the sovereignty over the submerged continental shelf extending from the Argentine mainland below the Atlantic Ocean is with Argentina, including islands on that continental shelf, such as the Falklands. In an exchange of notes of November 2, 1917, between Secretary of State Lansing and Viscount Ishii, Special Ambassador of Japan, occurs the following paragraph:

"The Governments of the United States and Japan recognize that territorial propinquity creates special relations between countries, and consequently, the Government of the United States recognizes that Japan has special interests in China, particularly in the part to which her possessions are contiguous."[90]

Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego

[edit]Beagle Channel cartography since 1881

East Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego and Strait of Magellan Dispute

Argentina's acquisition of Patagonia is discussed above.

Beagle channel

[edit]

An 1881 boundary treaty defined the border between Argentina and Chile.[91][92] It covered the established border as well as land to the south, including Patagonia, that was still largely unexplored, reaching down to the southern point of the continent. Its intent was to formalise the established principal whereby neither country had access to the other's ocean while also including the settlements already established and under the jurisdiction of one respective country. This meant, for example, that Chile was given sovereignty over both sides of the Strait of Magellan, due to its settlement at Punta Arenas, and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago was divided between both countries.[45] However, the border around the mouth of the Beagle channel on the Atlantic side, which included several islands, was not clearly defined and this led to a variety of interpretations for many decades as to where the boundary actually was. Clause 3, stated:

"In Tierra del Fuego a line shall be drawn, which starting from the point called Holy Spirit Cape (Cabo Espíritu Santo), at parallel 52°40’S, shall be prolonged to the south along the meridian 68°34’ west of Greenwich until it touches the Beagle Channel. Tierra del Fuego, divided in this manner, shall be Chilean on the western side and Argentine on the eastern. As for the islands, to the Argentine Republic shall belong Staten Island, the small islands next to it, and the other islands there may be on the Atlantic to the east of Tierra del Fuego and of the eastern coast of Patagonia; and to Chile shall belong all the islands to the south of the Beagle Channel up to Cape Horn, and those there may be to the west of Tierra del Fuego."[45]

There were no maps or further text to specify more exactly the course of the border through the Beagle Channel into the Atlantic , a course dotted with many small islands. This ambiguity is reflected in the maps drawn at the time, with each side interpreting the border to best suit itself. Initially, before it later lost favour, Chile interpreted "...to Chile shall belong all the islands to the south of the Beagle Channel..." to mean Argentine sovereignty stopped where the land ended, the 'dry coast principal'

A century of discussion in vain followed the 1881 treaty that wavered in intensity. In 1952, Argentina ignored a finding of the ICJ that awarded the Beagle Channel and the three strategically important islands of Lennox, Nueva and Picton to Chile. Citizen from both countries continued to use the islands. Argentina also refused to recognise the Courts jurisdiction in the matter. The islands and their territorial waters were important to Argentina because possession would strengthen it claim to part of Argentina. Ownership of the surrounding water had the addition advantage of allowing clearer access to the Atlantic for Ushuaia, its settlement at the base of Tierra del Fuego. After a few years of continuing fruitless discussion, tensions reached a head in July 1958 when Chile built a lighthouse on Snipe Island, an islet in the disputed channel used by Chilean shepherds. The Argentine navy destroyed the lighthouse, only for Chile to build another which Argentine forces also destroyed and then occupied the island. A solution was then reached in which both sides returned to the pre-1952 situation.[93]

In 1971, both parties agreed to arbitration by the UK that would result in a binding decision. In February 1977, that decision was released. Although it guaranteed access to Argentine ports in the channel, as it was a fundamental principal in international law, thus overriding the dry coast principal, the decision found mostly in favour of Chile. The ocean principal, whereby both sides were blocked from direct access to the other side's ocean, was of less relevance than the wording of the 1881 treaty that had not specifically excluded Lennox, Nueva and Picton islands, meaning they were Chilean, as "islands south of the Beagle Channel". Argentina unilaterally rejected that binding decision as flawed and it drew up a plan to invade the disputed areas: both governments, that since 1971 had become military dictatorships, were close to war.

In January 1978, both countries agreed to return to the pre-1977 status and to accept last minute mediation by the Holy See in the form of Cardinal Antonio Samoré. After a fortnight of shuttle diplomacy both sides signed an agreement in Montevideo in which they promised not to use to force against each other. His Eminence, having just averted war, reported back to the Pope on the "little that I have done".[94][95]

Two additional factors to consider before a more lasting settlement was later reached in 1984 with the signing of The Treaty of Peace and Friendship. First, Argentina's defeat in the 1982 Falklands War had created an Argentine public weary of war; second, was that the treaty would take precedence over the relevant section of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, that extended Chilean exclusive economic zone at Argentina's expense now that Chile had undisputed sovereignty over the LNP islands. The Treaty of Peace and Friendship was published in October 1984.[96] By the treaty, Chile agreed to a section of its waters in the Drake Passage being Argentine waters. This made more palatable to Argentine politicians and the wider public, the giving up of the claim to the PNL islands. Following a referendum the Argentine public accept the 1984 treaty terms and the government the reluctantly signed the treaty. It has been claimed that Argentina had bullied Chile into giving up its rights to that part of the ocean. The 1984 treaty confirmed most of the land borders from the 1977 arbitration while extending Argentina's territorial waters at Chile's expense. Following a plebiscite in late 1984, the Argentine public approved the draft treaty that was signed on 2 May 1985 and came into force in 1988.[45][97]

Despite the treaty, squabbles between the two countries about their maritime boundary still arise.[98][99][100]

Naval arms race

[edit]River Plate and Uruguay river

[edit]

brazil etc[101]

Following the Cisplatine War between Brazil and the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata (Argentina's precursor), in 1828 a Preliminary Peace Convention was signed and ratified; it recognised the independence of Uruguay. The southern and western limits of Uruguay were not defined in the Convention, although Article 12 implied that the right bank[b] of the Uruguay River was not part of the province of Montevideo. Throughout the rest of the 19th century, the boundary was not delimited, although various agreements were effected to guarantee free navigation of the river Plate and the Uruguay river.[102] After a series of agreements about the boundary from 1916 onward, in 1973, both countries signed the Treaty of the Rio de la Plata and its Maritime Limit. The boundary was determined by a series of geographical points along the course of the river Plata. These points created two types of zone, one of exclusive jurisdiction and another of common jurisdiction. In the former, either Party has authority without interference from the other while in the latter authority is held concurrently and by the CARP. The inner waters of both countries are drawn intentionally to let the navigable waterways lie within the common zones.

Martín García Island

[edit]Disagreements continued however, such as the Uruguay River pulp mill dispute from 2003 to a 2010, which followed the ICJ decision in favour of Uruguay.[103] The Martín García canal dispute, beginning in 2006, relates to Argentine dredging in and around the confluence of the two rivers that affect the already agreed navigation rights of shipping. Although these disputes have become heated, with Uruguay considering the possibility of military conflict,[104] the disputes between the two generally friendly countries are not referred to as being motivated by territorial nationalism.

The Andes mountain range

[edit]Southern Patagonian ice field

[edit]

1902 Arbitral award of the Andes between Argentina and Chile

Boundary Treaty of 1881 between Chile and Argentina

There were negotiations in 1990.[105]

- Rudolph, William E. (1934). "Southern Patagonia: As Portrayed in Recent Literature". Geographical Review. 24 (2): 251–271. Bibcode:1934GeoRv..24..251R. doi:10.2307/208791. JSTOR 208791.

- Allan, Laurence (2007). "Néstor Kirchner, Santa Cruz, and the Hielos Continentales Controversy 1991–1999". Journal of Latin American Studies. 39 (4): 747–770. doi:10.1017/S0022216X07003215. S2CID 143568484.

- De Lasa, Luis Ignacio; Luiz, María Teresa (2021). The Southernmost End of South America Through Cartography. The Latin American Studies Book Series. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-65879-3. ISBN 978-3-030-65878-6. S2CID 231673557.

The precise boundary between Chile and Argentina in the Andes around the Southern Patergonian ice-shelf was not defined in the early years of each county's independence because at the time the area was partly unknown and was not relevant to either side anyway. However, both the countries later attempted to demarcate the boundary and they signed the 1881 Treaty of cccccc. This defined the boundary as running along lines determined by water flow, from peak to peak in the mountain range. This was to be determined by an expert from either side, and if no consensus was reached in any area, a neutral third party expert was to make a final binding determination.

The boundary between Chile and the Argentine Republic is, from North to South, up to the fifty-second parallel of latitude, the Andes Mountain Range. The boundary line shall run in that extension along the highest peaks of said cordillera dividing the waters, and shall pass between the slopes that break off on one side and the other. The difficulties that may arise due to the existence of certain valleys formed by the bifurcation of the cordillera and where the dividing line of the waters is not clear, shall be resolved amicably by two experts appointed, one from each party. In case they do not reach an agreement, a third Expert appointed by both Governments shall be called upon to decide them. Of the operations carried out by them, a record shall be drawn up in duplicate, signed by the two Experts, on the points on which they have agreed, and also by the third Expert on the points decided by him. These minutes shall take full effect as soon as they have been signed by them and shall be considered firm and valid without the need for any other formalities or formalities. A copy of the minutes shall be sent to each of the Governments.[9]

Owing to ambiguities in the 1881 treaty, Boundary Protocol between Chile and Argentina 1893 was signed, but ambiguities and dispute continued. In 1902, the UK acted as an independent expert and determined that....

The problem can be summarised as the irreconcilable principles: the high point line between the mountain range peaks and the watershed line from which water will flow down to the Pacific or Atlantic ocean. Often these two lines are the same, but owing to the nature of the Andes which is in reality a series of interconnection cordesillas this is not always the case. Another complication in this ice field is that the watershed can change naturally. If xxxx were to melt....

In 1991, to overcome this irreconcilable problem, a polygonal boundary was proposed where the boundary would be straight lines between a few established mountain peaks, but neither sides government agreed to this. However, agreement was reached along much nof the boundary in vvvv, leaving only cgerj undefined in 2023.

Del Desierto lake

[edit]

The area in the Andes around Del Desierto lake along the border with Chile was not clearly marked by the 1881 treaty. As settlement in the area began, an ongoing dispute arose around ownership of 481 sq kms. This culminated in 1965 with the Laguna del Desierto incident, a clash between four Chilean Carabineros and a dozen members of the Argentine Gendarmerie in which a Chilean, Herman, Merino, was killed. The dispute was finally resolved in 1994 when an arbitration tribunal awarded the land to Argentina.[106]

The lake is known in Argentina as Lago del Desierto and in Chile as Laguna del Desierto.

Puna de Atacama dispute

[edit]

spanish John, Ronald Bruce St (1994). The Bolivia-Chile-Peru Dispute in the Atacama Desert. ISBN 9781897643143.

From the 16th century, Alto Peru, an area roughly equivalent to contemporary Bolivia was came under the jurisdiction of the Real Audiencia of Charcas, a division of the Viceroyalty of Peru. In 1776, Spain incorporated Alto Peru into the newly created Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, governed from Buenos Aires. When independence was proclaimed in Buenos Aires in 1810, Spain placed Alto Peru back under the authority of the still loyal Viceroyaly of Peru. Atacarma, an inhospitable desert region whose boundaries had been ill-defined by Spain but which Bolivia claimed, under uti possidentos as its own, based on earlier Spanish maps. Its critical relevance is that it gave Bolivia access to the sea alone a 560 km coastline. The settlement initially designated as Bolivia's port was Cobija but it soon became clear it would be too small. Boliva successfully lobbied the Peruvian government and a treaty was sign in 1826 in which Peru ceded to Bolivia land which extended Bolivia's coastline to the north, which included the larger port of Arica. However, the Peruvian congress failed to ratify the treaty.[107]

The matter lay dormant until 1879 when Chile annexed the coastal part of the Bolivian territory, known as the Litoral Department, which ignited the War of the Pacific. By the end of the war in 1884, with an acceptance by Bolivia of the loss of its coastline, (although a formal peace treaty would not be signed until 1898), Chile had also occupied areas in the Atacarma desert. Argentina pointed out the region was still subject to a border dispute between itself and Bolivia. Chile claimed the Atacarma desert was Bolivian territory, not Argentina's. Bolivia proceeded to sign two secret treaties, one with Argentina in 1889, giving Buenos Aires all the Puna de Atacarma, and one with Chile in 1891, ceding to Chile all land in the Puna occupied by Chile since the war's end. In 1898, with the treaties no longer secret, both Argentina and Chile agreed the US ambassador to Argentina, William Buchanan, could make a binding boundary decision, which he did. Argentina acquired 85% of the Puna de Atacarma with the rest given to Chile.[108]

Antarctica and wider geopolitics

[edit]Background, the Antarctic Treaty System and wider geopolitics

[edit]From the late 19th century until the Second World War, a select handful of countries jostled for positions of authority in Antarctica, on the mainland and on surrounding islands. This involved dividing the continent into pie shaped sections and creating numerous interconnected agreements and treaties between themselves, all of which gave the structure an air of authority. The UK section was formally established in 1908 and continues today as the British Antarctic Territory (BAT).[109] Unlike efforts at land acquisition elsewhere, effective occupation, a key component of establishing sovereignty rights, was impossible in Antarctica. This led to a closer reliance on prior discovery, exploration and a weaker form of occupation, mainly through the use of whaling stations.[110] The 1928 Palmas decision appeared to support this approach when it said: "Sovereignty cannot be exercised in fact at every moment on every point of a territory. The intermittence and discontinuity compatible with the maintenance of the right necessarily differ according as inhabited or uninhabited regions are involved."[111] The countries included in this pre-WW2 group were the UK (including Australia and New Zealand, as part of its wider empire), Norway, France, Germany, Russia (and the USSR) and the USA. Chile and Argentina were rarely involved, if at all, during this period: their claims began being made more explicitly during the 1940's which included claims of sovereignty rights over pie shaped sections of their own, both of which overlapped each other and the already establish British section.

One reason for Britain's Operation Tabarin in 1943 was the potential threat to the Falkland Island Dependencies from neutral Argentina with its perceived pro-German leanings. Tensions hardened post-war, with Argentina's increasingly assertive nationalist stance compounding the determined positions of other states with wider cold-war considerations. The need for some form of international agreement was becoming pressing. An example of Argentina's growing asseriveness after the war was the "Instituto de Geográfico Militar which produced most of Argentina’s official maps, began promoting the broader idea of national grandeur and manifest destiny as it became enamoured of the country’s so-called territorio nacional" which comprised the various territorial claims - including its Antarctic wedge.[112] In an attempt to resolve the sovereignty issue and perceived threat to it's Antarctic and sub-Antarctic territories, Britain applied to the International Court of Justice more than once, such as in 1956,[113] but Argentina refused to participate, which meant the applications did not proceed any further. A 1939 suggestion by a Chilean lawyer to suspend all sovereignty claims and focus on scientific research now began to take root with similar proposals put forward by other interested parties.[114] In 1957-58, The International Geophysical Year (IGY) took place which in 1959 led in to the signing of the Antarctic Treaty by a group of twelve countries with historic links or current active research activity in Antarctica.[115][116] All existing sovereignty claims were frozen and military activity south of latitude 60* South was banned: scientific cooperation and research was encouraged.[117] The treaty's simplicity and enduring strength has been lauded as “unique in history" - "[The treaty's existence being one] which may take its place alongside the Magna Carta and other great symbols of man’s quest for enlightenment and order.”[118] It allows states with diametrically opposed opinions to coexist in a "purgatory of ambiguity".[119] Despite its success, it should not be forgotten that the treaty has not solved the sovereignty issues and the sovereignty card awaits being dealt by any claimant state as and when any given future situation might arise.[119] There are currently seven countries with claimed sovereignty over parts of Antarctica: Norway, France, Chile, Argentina, New Zealand and Australia. The USA and Russia have both asserted they have the 'basis of a claim', meaning they reserve the right to make future sovereignty claims of their own. Unlike their rejection of the UK claim, Argentina and Chile recognise that each has sovereignty rights in Antarctica, meaning their difference is only about where the border between their sections should lie.[120]

The Antarctic Treaty is the centre point of what had become an increasingly interwoven mesh of international agreements, collectively known as the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). The ATS provides a valuable model for international structures that avoids seemingly irreconcilable sovereignty and boundary issues,[121] In a 20xx paper, Hemmings et al identify eleven reasons why such sovereignty disputes arise in Antarctica.[122] Of these numerous agreements within the ATS, a significant one is the 1991 Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Madrid Protocol), with 26 original signatories, rising to 42 in 2022. The Madrid Protocol has prohibited any activity relating to mineral resources, other than scientific research.[123]. Argentina's territorial claims in Antarctica are still expressed with irrefutable determination, but the ATS has been effective in restricting the Falkland Islands dispute from spreading into the sub-Antarctic, as it had done in the 1950s.[124]

The Antarctic is a major interconnected part of what has been described as the geopolitics of the Southern Cone, an area expanding towards Latin America from the South Pole, in which the various states vie for superiority on a variety of issues, not only land. Jingoism and overt nationalism, as expressed by Argentine governments, both military and civilian, are features of this geopolitical thinking.[5]

Basis of Argentina's claim

[edit]Despite some uncoordinated or indirect connections with Antarctica from the late 19th century, Argentina's formal claims to part of the continent (Antartida Argentina) emerged in the 1940s as a repudiation of Britain's claim to a section of Antarctica, which included the Antarctic Peninsula, (and of Chile's claim, also made in the 1940s). All three claims substantially overlap each other, with Argentina's claim lying fully within territory claimed by one or both of the other two countries. Both South American claims are rooted in the doctrine of uti possidetis juris, whereby Spain's territorial claim was transferred to the successor states at independence.[125] However, other grounds for its claim have been espoused, allowing it to be viewed more specifically as resting on four pillars (one being uti possidetis juris). Of these four only one carries any weight.[126]

- First, as mentioned, is uti possidetis juris: that Argentina inherited Spain's claim to Antarctica, notwithstanding that Spain had no claim, at least not one that would stand up to closer scrutiny in contemporary international law. This blunt dismissal of the uti possidetis argument can be traced back to the 1493 Papal Bull discussed earlier in this article.

- Second, is the principle of contiguity, meaning Argentina and Antarctica are in some way connected geographically, [2], a concept that has no basis in international law.

- Third, geological affinity, which means, put simply, the Andes is one mountain range that submerges at Tierrra del Fuego and re-emerges on the Antarctic continent.[127]

- Fourth, and the one with some legal merit, is effectivités (effective possession), based on obtaining a weather station on Laurie Island in the South Orkney Islands in 1904 and continuously manning it ever since.[128][129][130]

The shortcomings of the claim are reflected in the Argentine government's lengthy, platitudinous statement in 2023 that asserted sovereignty over a designated sector of the Antarctic continent, over some off-shore islands, and over territorial waters out to 200 nm with the associated seabed and resources. That 2023 assertion reads: "Argentina reaffirms sovereignty over the Argentine Antarctic Sector extending between the 25th and 74th meridians of west longitude, south of the 60th parallel of south latitude." The basis on which such a claim is made is missing, beyond an indirect assertion that Argentina has had the longest continuous presence in Antarctica, referring to its 1904 purchase of the Scottish base on Laurie Island.[131] More detailed references to Argentina's involvement in the exploration of Antarctica and the surrounding islands can be found in articles by Latin American authors, but these amount to not much more than indirect connections with a sovereignty claim,[132] or they simply dismiss certain facts as not relevant, such as the UK's 1908 Letters Patent establishing the Falkland Island Dependencies. It (WHAT?) said: "However, the declaration passed mostly unnoticed, probably considered an internal British administrative act of no significance."[133]

Determined promotion of claimed sovereignty rights by Argentina

[edit]In 1965, Argentina sent an expedition of military personnel to the South Pole, known as Operación 90. It was carried out in secret, with its primary aim being to strengthen Argentina's claim to part of Antarctica. It is the only known case of military manouvres on the continent, something which is prohibited by the Antarctic Treaty.[134]

The less bellicose Argentine government continues to convey no less a determination to remind its citizens that the Antarctic Treaty has not affected the status of its Antarctic sector, a practice to an extent also adopted by the other claimant states.[135]

To strengthen its territorial claim, Argentina has arranged for pregnant women to be taken to bases in its Antarctica Argentinas region to give birth. This practice was shared by Chile and resulted in a freezing baby race.[136] The first child born on the continent was Emilio Marcos Palma in 1978, at an Argentine base near the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. Since then several more children have been born in Antarctica, all at Argentine or Chilean bases.[137]

Tourism provides a simple way to promote Argentina's claim, with regular cruises departing from Usuawaia.[138]

The Falkland Island Dependencies

[edit]bluster bludgion

From the beginning of the 2oth century, Britain had long term ambitions to bring Antarctica into the British Empire.[139]

The Falkland Island Dependencies have been been claimed by Britain in stages from 1843, most notably in Letters Patent in 1908.[140][141] They were administered from the Falkland Islands but constitutionally were separate from them. They comprised the Antarctic Peninsula and Graham Land on the Antarctic mainland as well as the South Shetland Islands, South Georgia, the South Sandwich Islands and the South Orkney Islands. They were uninhabited and any human activity around them related primarily to the whaling industry.

Argentina first raised its sovereignty claim over South Georgia indirectly in 1927 and began to lodge claims more formally to all the Dependencies during the 1940s, beginning in 1943.[142] However, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands lay outside Argentina's stated area of claim.[143] Later, during WW2, the British government was worried both about the Argentine claims and the possibility that the undefended dependencies would be used as safe anchorage by German U-boats for attacks on Allied shipping rounding Cape Horn. Consequently, in 1943 the government set up the top-secret Operation Tabarin.[144] In addition, it was to carry out scientific reseach and to acquire important navigational and meteorological data. In 1944, the expedition team of 14 had built four bases, three being year-round, on Deception Island, Hope Bay and Port Lockroy. The team grew and in July 1945, after the European war had ended, the operation was renamed the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS).[145] Argentina intensified its provocative stance: for example, it resumed its requirement that Falklanders wanting to enter Argentina had to hold Argentine passports, a notable problem for parents who sent their children to school on the mainland.[146]

In 1955, the UK instituted proceedings before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against Argentina and Chile for a definitive ruling on the sovereignty issue regarding the disputed Antarctic and South Atlantic territories. Both countries refused to acknowledge the ICJ's jurisdiction and so the application was withdrawn.[147] This case was one of five brought by the UK between 1948 and 1956 to have the matters settled by a neutral third party and on each occasion Argentina refused to submit to the ICJ's jurisdiction. One the face of it, this attitude is "hardly consistent with a belief that its claim was demonstrable".[148] However, an ICJ decision on the Falkland Island Dependencies, whatever the outcome, could have been seen as an indirect acknowledgement by Argentina of British sovereignty over the Falkland Islands themselves, which would thus provide an alternative interpretation of Argentina's stance.[149] As of 2015, Argentina continues to assert its "unquestionable rights and titles derived from and based on legitimate methods of acquiring territorial domain and effective, notorious and peaceful possession." Such vague generalities make it nigh on impossible to reach a resolution.[148]

South Orkney Islands, including Laurie Island - the roots of British procrastination and Argentina's ace in the hand

[edit]Graham Land including the Hope Bay incident, 1952

[edit]The British base at Hope Bay at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsular burned down in the late 1940s. In February 1952, a small British scientific party arrived aboard John Biscoe and began unloading supplies to rebuild the base. However, a group of armed Argentine soldiers was constructing their own base a few hundred meters away, supplied by the "Buen Suceso anchored offshore. The Argentines confronted the British party and ordered them to leave, saying they were acting on instructions from Buenos Aires. The British group ignored this demand and carried on unloading. Shortly afterwards, the Argentines fired a few machine-gun rounds over their heads and forced the British party to return to the John Biscoes. "Our party obeyed Argentine officer's cocked pistol" was the message sent to Miles Clifford, Governor of the Falkland Islands. The next day and ignoring London's wish for restraint, Clifford accompanied HMS Burghead south with an attachment of marines. A few days later, the British shore-party landed again and finished re-building their base, safe under the cover of naval guns. The unarmed British party was left ashore to over-winter with the nearby Argentine group, but despite worries in London about the "trigger-happy South Americans" there was no further incident.[150] The government of Juan Peron apologised and put the event down to a misunderstanding by the officer in charge. However, the Argentine party later returned home to a hero's welcome.[151]

South Shetland Islands including the Deception Island incident, 1953

[edit]In January 1953, an Argentine party constructed a base in the South Shetland Islands next to the existing British base at Deception Island, a partly submerged volcanic cone that provides an excellent nature harbour. From South Georgia, HMS Snipe with 35 marines was sent to Deception Island. On 15 February, it found the Chilean hut empty and the two occupants of the Argentine hut were duly arrested without a struggle. They were later repatriated and the huts were removed. There was concern at the time that the incident would provoke an Argentine attack on the other British bases or to retake Deception, but that did not eventuate. However, HMS Snipe's captain was told that the island must defend. Unlike media reports that covered the incident humorous, the UK government treated it with utmost seriousness. The prime minister, Winston Churchill, said: "The Admiralty should be asked to consider naval reinforcements..It would be very bad if we were made fools of by the impudent and lawless trash that are confronting us." The situation remained tense and later in 1953, there were repeated sightings of unknown aircraft flying over the Falklands. It has been argued by the author Patrick Armstrong that Argentina was testing British resolve in 1953, an approach similar to the scrap-metal workers on South Georgia in 1982.[146]

South Sandwich Islands, including Thule Island

[edit]Procrastination[152]

RSS of Franks[153]

Thule Island is one of three comprising the Southern Thule group at the southern end of the barren and uninhabited South Sandwich Islands. In the 1954-55 summer season, an Argentine party from ARA General San Martín built the refuse hut 'Tentiente Esquivel' on Thule, which was occupied in the 1954-55 and 1955-56 seasons during which some scientific research was carried out. The occupation also was also used to strengthen Argentina's claim to the island group. In January 1956, the shore-party was evacuated following a volcanic eruption on nearby Bristol Island.[154][155]

According to Secret Decree 2085, from 18 July 1977, and signed by then head of the military General Junta, Jorge Rafael Videla, the ministry of Defense through the Navy's Command was authorized to continue and complete the logistic tasks and aspects for the mounting and necessary equipment leading to the effective and peaceful occupation of the island of Thule, part of South Sandwich islands.[156] In 1976, Argentina returned and built a more substantial base for around 20 military personnel on the island, calling it Corbeta Uruguay. On 29 December 1976, a helicopter from HMS Endurance on a routine visit flew over the island to collect some scientific equipment left earlier and saw the Argentine base. The Argentine personnel greeted them but in the poor weather the British were initially confusion due to the different languages and the base's name which implied the occupants were from Uruguay. Once the situation had been clarified, the Endurance left and reported to London on 4 January 1977. The British government chose to seek a diplomatic solution to the occupation, that was kept secret from the public gaze. To strengthen its hand, and to counter any possible threat to the Falkland Islands, a small but powerful naval force, called Operation Journeyman, was dispatched: it included a nuclear powered submarine. The base was left there, no further escalation occurred and the operation was deemed successful.[157] At the end of the Falklands War in 1982, British forces returned, removed the occupants without a struggle and later that year destroyed the base.[158][159]

South Georgia

[edit]- freedman

- Headland, Robert (1984). The Island of South Georgia. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521424745.

As with the other Dependencies, the UK made formal claim to South Georgia in Letters Patent in 1908. Until then, their status was ambiguous - Britain had made reference to them in various documents and in South Georgia, first mentioned as a Dependency in 1887, the Falklands Islands Government had exercised some jurisdiction. In 1909, a Stipendiary Magistrate was appointed for local administration of the population of around 720 related mainly to the whaling industry, of which 80% were Norwegian.[160]

Argentina's claim to South Georgia, and the South Sandwich Islands, is not clearly stated, although if based on inheriting the Spanish claim the claim is spurious: there is no record of any such claim, and if the claim is based on the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, which Argentina has used to justify territorial claims elsewhere, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, were within Portugal's sector.[143] It is possible any claim could be based on a tenuous association with the Falkland Islands. This is because Britain's treatment of the legal connection between the Falklands Islands and all the Dependencies has at times been ambiguous, creating a semi-amalgamation of all the territories.[161] Argentina has also stated that it acquired sovereignty over South Georgia in 1904 when its whaling and fishing company, "Compania Argentina de Pesca" established the first permanent settlement there, before Britain's 1908 claim. However, When the company's first cargo arrived in Buenos Aires in 1905, the Argentine government treated it as arriving from a foreign port and charged customs duty. In the same year, a government official, acting on behalf of the company, applied personally to British authorities in Buenos Aires fro a 21-year whaling licence, that was granted.[148] There was no objection to Britain's sovereignty at any stage until Argentina first made reference to its claim in 1927, to the International Postal Bureau in Berne. When the Argentine government reaffirmed its claims in the Antarctic and South Atlantic in 1943, South Georgia fell outside the stipulated latitudinal and longitudinal area.[162]

The Falkland Islands

[edit]

- Franks Report

- Falklands War in International Law (Phd thesis subsequently published..p157)[163]

- 1976-82[164]

- Armstrong, Patrick (1998). "The role of the Falkland Islands and Dependencies in Anglo–Argentine relations in the early 1950s". Polar Record. 34 (188): 53–55. Bibcode:1998PoRec..34...53A. doi:10.1017/S0032247400014984. S2CID 129644661.

- Ben Hunt, W. (24 March 1997). Getting to War: Predicting International Conflict with Mass Media Indicators. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472107518.

- Argentina laid claim in 1927.parsons

- United States Involvement in the Falkland Islands Crisis of 1831-1833

- poss good

- beck

- [whose island story by beck 1989]

- [3] Argentina's Fernandez takes Falklands claim to U.N.

- letters patent 1843

- [4] 1982 US view of Argentina's motives in falk war, geopolitical nb p40*study of the uk reoccupation in 1833

- [165] The British Reoccupation and Colonization of the Falkland Islands, or Malvinas, 1832–1843

- [5] uk govt position

Latin tricks, prods and pricks, 1962-1982

[edit]shackelton p18

Territorial waters

[edit]

Argentina has long taken an interest in the jurisdiction of the seabed along its coast, extending out into the ocean and including waters around British South Atlantic islands and Antarctica. In 1974, a report prepared for the US Office of the Basic Geographic Intelligence, said Argentina's primary objective was to establish its jurisdiction over petroleum resources and extensive fishing rights.[166] In 2009, Argentina submitted a claim to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), whose role is defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The claim covered the area around the Falkland Islands, South Georgia, the South Sandwich Islands, the Antarctic Peninsula and nearby islands. The CLCS report was published in 2016 and it was reported at the time that a decision of the CLCS had expanded the territorial waters of Argentina by accepting the area Argentina claimed as its underwater continental shelf. Argentina's foreign minister Susana Malcorra said the report was an "historic" decision "reaffirms our sovereignty rights over the resources of our continental shelf."[167] This would, it was claimed, allow Argentina to extend its projected work on offshore oil resources over what was now determined to be an Argentine seabed. Also in 2016, La Capital, a widely read Argentine newspaper, pronounced that a "New map of the maritime platform reaffirms the sovereignty of the Malvinas with UN endorsement".[168] Later, in 2020, Argentina passed a law unilaterally extending its territorial waters, thereby doubling the country's size.[169] However, the same science used in the 2016 CLCS report would be no less useful to the UK in establishing its claim to the seabed around its South Atlantic islands. In any case, the CLCS, comprising scientists, did not make, and is prohibited from making, any decision regarding claims to the seabed: its role is purely scientific, making these nationalist territorial pronouncements simply wrong and amounting to much ado about nothing.[170]

Earlier in 2008, the issue of sovereignty of the sea bed became more relevant when an oil rig from Scotland, Ocean Guardian, arrived in waters north of the Falklands, with plans for test drilling. An argument broke out between Britain and Argentina due to the potential large commercial benefits that might arise from resources beneath the sea bed.[171]

In 2010, the International Boundaries Research Unit (IBRU) at Durham University published a series of maps illustrated the complexities of the competing claims by Argentina and Britain in the South Atlantic and Antarctica.[172]

The Argentine foreign ministry continues asserting the disputed waters are Argentine. In 2022, it was quoted as saying it was appropriate "to reflect on the magnitude of the Argentine maritime spaces, which double mainland territory, plus its significance for the sovereignty rights Argentina possesses over the maritime spaces and insular territories.".[173]

Fishing, oil and gas