Draft:Ca' Morta tomb

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 4 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 3,203 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

Tomba di Cà' Morta | |

Negau helmet discovered in the Ca' Morta tomb | |

| |

| Alternative name | Tombe III/1928 Casa di Morti |

|---|---|

| Location | Italy |

| Region | Italy |

| Coordinates | 45°49′00″N 9°05′00″E / 45.81667°N 9.08333°E |

| Length | 0,64 m2[notes 1] |

The Ca' Morta tomb is a Celtic chariot tomb located in the necropolis of the same name to the west of the city of Como, in Italy's Lombardy region. The burial chamber, covered by a tumulus, contains the ashes of a woman of princely status, accompanied by furnishings. Thanks to the exceptional quality of the objects unearthed, this tomb is a precious testimony to Celtic culture at the time, particularly in terms of craft techniques, intra-European trade and the role of women in society.

The material evidence shows that the deceased was of Celtic origin, and that the site belongs to the Italo-Celtic "Golasecca" culture, which, like the Hallstatt culture, is a Celtic culture in Early Iron Age Europe.

While the burial area was first excavated in 1891, the tomb was discovered in 1928. Radiocarbon analysis reveals that the foundation of the tomb dates from approximately the middle of the 5th century BC (-450), which means that this Italo-Celtic burial site can be attributed to the "Golasecca III / GIIIA" period, and more precisely to the "eastern" facies of the Golasecca culture.

Among the artifacts discovered, archaeologists note a remarkable four-wheeled chariot. The vehicle, used for ritual purposes, displays features typical of the "Hallstatt culture". The abundance and refinement of the furnishings found in the burial site suggest that this was a princely tomb: the objects are all of high-quality workmanship. Numerous items of Etruscan laminated bronze crockery and Attic black-figure and red-figure ceramics evoke trade relations with Padanian Etruria on the one hand, and Magna Graecia and the Italic territories on the other.

Among these objects, archaeologists unearthed a Negau helmet,[notes 2] the only weaponry found in the tomb.

Finally, numerous elements - ancient, epigraphic, and archaeological sources - indicate that the woman, whose cremated remains lie in the urn of "tomb III/1928", was probably of Orobian stock, and that her mother tongue was Lepontic.

Discovery and excavation[edit]

The Ca' Morta tomb[notes 5][notes 6] was discovered in 1928 by the landowner, Giuseppe Butti, following a landslide and subsequent landslide in the eponymous necropolis.[1][2]Antonio Giussani of the Società Archeologica Comense (Comascan Archaeological Society[notes 7])[1][3] carried out the extraction, identification and inventory of the various pieces and artifacts contained in the burial cellar. With the support of his team of archaeological researchers, Giussani also brushed, cleaned and deoxidized the archaeological material discovered.[3][1]

All the pieces were entrusted to the then Director of the Como Archaeological Museum1, the architect Luigi Peronne. He took charge of restoring and reconstructing the chariot, since when the tomb was uncovered, the funerary vehicle appeared fragmented.[3][1][4]

These initial excavations were not exhaustive, as a second inspection in 1930 unearthed a final piece: an elaborate bronze kylix, probably of Attic origin.[1][5][6] In the necropolis's archaeological registers, the Ca' Morta tomb is listed, then recorded under the technical designation: "Tomb III /1928".[1][6][7][8][notes 8]

Context[edit]

Chronological and geographical context of the Ca' Morta tomb[edit]

The Cà' Morta burial site was discovered on the southern outskirts of the city of Como, in Lombardy, in the continuation of an avenue: Via Giovanni di Baserga, in the Albate district.[1][4][2][9]

Analysis of the archaeological material extracted from the burial vault confirms that it dates from the second half of the 5th century B.C.[8][10]

The burial site lies within a vast cemetery known as the "Ca' Morta necropolis". This burial complex, discovered in the 19th century, has been the subject of several excavation programs, including one by Ferrante Rittatore Vonwiller.[11][12][13] As a result, several other tombs were uncovered. Examination of their funerary material enabled us to determine the different chronological stages of the necropolis.[notes 9][14] In addition, analysis and interpretation of the Viatics,[notes 10] comprising artefacts such as ceremonial objects, bronze votive offerings, painted crockery and ceramics, revealed the importance of trade between the Comascan territory and other regions: primarily Padanian Etruria, Magna Graecia and the Celtic Hallstatian culture.[15][12][16][17][18]

The objects and remains found in the necropolis date its construction to between 750 and 700 BC, during the Early Iron Age.[6][8][19][20] Nevertheless, a significant number of markers, such as manufactured products and ruins of mortuary structures, lend credence to the hypothesis of the re-employment of a protohistoric cemetery dating from the Middle to Recent Bronze Age.[notes 11][21]

Vestiges of settlements, none of them with monumental features,[notes 12] have been discovered in the vicinity of the Cà' Morta necropolis. On the whole, the infrastructures uncovered from the outcropping strata at the comasque site of Monte della Crocce[8][22] show a variety of architectural types: sometimes aristocratic, more frequently artisanal, agricultural, but essentially residential. This observation is consistent with the fact that the form of urbanization on the princely Comasque site is village-like.[8][22][notes 13] Moreover, both the small number and the architectural style of the remains confirm the development of proto-Italian urbanism.[8][10] They rest on a north-east-south-west axis.[8][10] Archaeological excavations have provided significant clues to corroborate the previously established chronological conclusions. The foundation of the princely site,[notes 14] adjacent to the burial complex, has been dated to around the end of the 7th century B.C.[23][19][24][25][26] However, these protohistoric ruins may have been preceded by various types of housing infrastructure. To this end, archaeological field investigations and surveys have revealed the remains of settlements to the west of the Comasque agglomeration. Stratigraphic expertise allows us to date the domestic ruins to around the beginning of the 10th century B.C.[8][27]

- Geographical location of the Ca' Morta burial site and the protohistoric site of Como.

-

John Baserga Street.[notes 15]

-

Albate district.[notes 16]

-

Como's position in relation to its lake.

-

The hill on which the protohistoric Comasque princely site once stood.

In addition to the Ca' Morta necropolis, excavations in the surrounding area have revealed two other sepulchral areas, whose evolution frames the aristocratic site of Como. Stratigraphic analyses reveal that both necropolises were founded after the princely center (early 6th century BC). The latter, much smaller in area than Ca' Morta, are located to the north-west, in the present-day Comascan suburb of Ronchetti di Rebbio, and to the east, in the district of Santa Maria di Vergosa.[8][28] During the 5th and early 4th centuries B.C., the Comascan aristocratic urban center and its three adjoining necropolises developed simultaneously as a result of a process of synœcism.[notes 17] During this period, the growth of the Comasque pole was continuous. The city grew to a maximum area of 150 hectares by the end of the 4th century B.C.[8]

Numerous epigraphic material occurrences, such as the Prestino inscription,[29][30][31][32][33][notes 18] show that Celtic tribes[notes 19] settled in the Comasque region several times during the same period. This fact is confirmed by a wealth of literary documentation, provided by certain ancient sources.[notes 20][34]

Consequently, given their chronological simultaneity and geographical homogeneity, some authors conclude that there is a highly probable cause-and-effect relationship between the two phenomena: on the one hand, the settlement of Celtic tribes at the precise point of Como / Ca' Morta, and on the other, the development of urban growth.[26][34][35][36]

- The epigraphic dedication discovered at Prestino di Como near Como.

-

Prestino's registration[notes 21]

Many historians believe that trade between the Comascan site and Etruria was constant from the 6th to the 4th century B.C.[8][37][38][39] In this respect, many of the coins discovered were found in the vicinity of the Etruscan aristocratic center. These include coins from the city of Populonia.[40] The "lion" coins were found embedded in the first stratigraphic layers on the southern slopes of the suburb of Prestino di Como.[8][37][38]

- Etruscan coins discovered near the archaeological burial site.

-

Typical coin of Populonia minted "with the lion", issued during the 5th century B.C.[notes 22]

-

A type of Etruscan coin from the city of Pufluna, discovered near the protohistoric site of Como.

In addition, multiple clues also discovered on the burial site, within the proto-urban remains,[notes 23] attest to a significant decline from the early 2nd century BC onwards.[8][35] Specialists such as Wenceslas Kruta attribute this decline to the Celtic invasions.[41] Analyses of the subsoil show that this decline continued in the following centuries (1st and 1st century BC), with the number of burials, together with the number of urban and peri-urban settlements, declining significantly. As a result, this evidence points to a significant decline in the political, economic and demographic influence of the princely city.[35][26][notes 24] Taking into account the historical background, this fact could be correlated with the rise of the Roman Republic. During the 1st and 2nd centuries BC, Roman republican power pursued a policy known as expansionism, in other words, a strategy of territorial, economic and cultural enlargement.[35][42] In fact, at this time, the territory was integrated into the Roman region of Cisalpine Gaul.[35][42][43] The decline, then abandonment, of the princely site of Como could therefore be the consequence of this Roman political logic.[21][42][44]

Chronological perspective[edit]

Summary table of different dating systems in Europe during the Hallstatt period.[edit]

| Archaeological dating system for Europe | Timeline | Events in Europe | Hellenistic world | Italian - Etruscan world | Celtic world | Celtic world | Celtic world | Celtic world |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South German Celts | Gallia comata | Eastern European Celts | Golaseccian Celts / Northwest Italy | |||||

| Bronze Age | 1200-1100 BC / 11th century BC | Mycenaean Greece/Cypro-Minoan syllabary | Helladic chronology IIIC1 | Culture de Terramare | Hallstatt culture A1 | Bronze Age final IIA | Hallstatt culture A1 | Culture de Canegrate |

| Iron Age | 1,100-1,000 BC / 10th century BC | Mycenaean Greece/Cypro-Minoan syllabary | Helladic chronology IIIC2/IIIC3 / Mycenaean Greece | proto-Villanovan culture | Hallstatt culture A2 | Bronze Age final IIB | Hallstatt culture A2 | |

| 1000 to 900 BC / 10th century BC | Celts Migration | Geometric art | proto-Villanovan culture | Hallstatt culture B1 | Bronze Age final IIIA | Hallstatt culture B1 | Proto-golaseccian | |

| 900-800 BC / 9th century BC | Fondation de Carthage -814 | Geometric | Villanovan culture I | Hallstatt culture B2/B3 | Bronze Age final IIIB | Hallstatt culture B2/B3 | ||

| 800 to 700 BC / 7th century BC | Founding of Rome-753 / Oldest tomb in the Golasecca culture: "del Carretino" tumulus | Geometric art | Villanovan culture II | Hallstatt culture C | Ancien Hallstatt culture | Hallstatt culture C | Golasecca IA | |

| 700 to 600 BC / life century BC | Tumulus of Baden-Württemberg / Acquisition of writing at Golasecca / Rise of the first Golaseccian proto-urban site: Castelletto sopra Ticino/ early Celtic proto-urban sites | Orientalist period | Villanovan culture III | Hallstatt culture C/Ha C | Hallstatt culture C/Ha C | Gollasecca 1B / 1C | ||

| 600 to 500 BC / life century BC | Roman Monarchy / Foundation of a proto-oppidum in Como / Cà' Morta tomb / Expansion of the Como oppidum / Extension of the Cà' Morta necropolis | Archaic Greece | Etruscan civilization | Hallstatt culture D | Middle to Late Hallstatt | Hallstatt culture D | Golasecca 2A / 2B | |

| 500 to 400 BC / 5th century BC | Massillia Foundation 400 | Etruscan monarchies | Hallstatt culture D/Ha D | Middle to late Hallstatt/Middle to late HA | Hallstatt culture D/Ha D | Golasecca 2B / 2C | ||

| Middle Iron Age | 400 to 300 BC / 4th century BC | Sack of Rome (384 BC); Battle of Allia; conquests of Alexander the Great and extension of Celtic koinè; Gallic invasions of northern Italy | Foundation of Massillia - Classical period | Roman Republic | La Tène A | La Tène Ancienne | La Tène A | Golasecca III |

| 300 to 200 / 2nd century BC | Battle of Sentinum (295) / Celtic military expedition led by warlord Brennos against Delphi (279) | Hellenistic period

(until 227) |

La Tène B | La Tène moyenne | La Tène B | La Tène moyen / La tène B | ||

| Late Iron Age | 200 to 100 BC / 1st century BC | Siege and fall of Numance (133) / Roman victory over the Celtic coalition on the Rhône of the Arvernes and Allobroges led by King Bituitos (121) | Greece in the Roman era | La Tène C | La Tène tardive | La Tène C | Romanization of the territory of the Golasecca culture (geographical area of the Italian Celts) | |

| 100 to 27 / 1st century BC | Gallic War (58/50) / Battle of Alesia 52 / Rise of the Roman Empire (27) | La Tène D | La Tène récente | La Tène D | Province of the Roman Republic / Celto-Italian territory integrated into the Roman province of Cisalpine Gaul (81, then 42) |

=== Geocultural perspective

===

On the map, "Tomb III/1928" of the "Ca' Morta" necropolis is represented by the red four-pointed star. The burial site lies south of Lake Como, one of the two main proto-urban centers of the Golasecca civilization, which established itself as a European center of trade and geopolitical flows during the 7th and 7th centuries B.C.[49][50][51][52] This important center is attributed to the "eastern" archaeological typology of the Golasecca chrono-cultural extension area,[notes 25] "Golasecca type 1".[49][50][53][54][55]

Description of the Ca' Morta tomb[edit]

The entire burial structure is covered by a voluminous tumulus made up of an agglomerate of rough granite stones, amalgamated with rich clay soil.[6][56]

The upper part of the burial vault, or sepulchre, takes the form of a large, elaborate limestone slab of remarkable dimensions: 1.8 m x 1.4 m. It weighs approximately 1.8 tonnes.[6][56]

The lower part of the grave, the pit, is 80 cm square, providing a space for the deceased and his or her viaticum[notes 26] of approximately 0.64 m2. Its depth is approximately 70 cm.[6][8][56]

Objects and artifacts unearthed[edit]

The parade float[edit]

- Ca' Morta burial chariot and typical funerary chariot of the Hallstatt civilization

-

Reconstruction of a chariot from the Final Hallstatt period.

This is a Hallstatt-type bronze "parade chariot" manufactured using a rolling technique. When first discovered, it was presented in the form of individual pieces; it was subsequently reconstructed and restored at the Como Archaeological Museum.

It is fitted with four identical wheels, made of bronze, oak and iron. Only one was found intact. The other three, in fragmentary condition, had to be restored. The wheels measure 96 cm in circumference. Each wheel has ten bronze spokes in the shape of a hose. They are also iron-rimmed. Analyses and studies by Luigi Peronne and his team determined that this strengthened the wheels during use.[55][57][58]

The other parts of the chariot are also worked in laminated bronze and ornamented (notably the balustrades and the vehicle body). In addition, the body is large compared to the other components.[6][59][58] It was found to contain a cinerary urn.[6][60][58] This parade vehicle also features a repoussé blade.[61][notes 27]

The chariot from burial site "III/1928" at Ca' Morta is thought to have been made in a wheelwright's workshop close to the discovery site.[52]

The kylix[edit]

The kylix (or Greek-type chalice)[notes 28] is identified as having an Attic origin[59] by Professor Raffaelle Carlo De Marinis.[62] Made of cast bronze and decorated by incision with a spatula, this vase features "red-figure" motifs.[notes 29] This kylix appears to be the only example attested in a funerary context in the Golaseccian territory. In addition, the drinking vessel is fitted with a foot of considerable height. After analysis of several fragments, its composition was found to be homogeneous: the content of tin and copper, the two metals making up the alloy, is constant throughout the object.[6][59][63]

Unidentified during the first excavations in 1928, the object was found on its own in 1930, during a second dig. It enables us to establish a more precise date for the foundation of the burial site; the burial chamber and its viaticum are thus associated with the Golasecca III period.[6][59]

The helmet[edit]

A Negau,[64][notes 30][65][66][67][68] helmet from the Golasecca III period was discovered in the cremation tomb. This archaeological artefact is crafted in bronze using a "laminating by superposition" technique of hammered sheet metal. The helmet is circular at the base, while the top has a conical appearance.[64] Its overall height is around 17 cm, and the diameter of its lower part measures 21.3 cm. Some of the bronze sheets covering the middle part of the headgear have been corroded and only fragments remain.[64] It is on display at the Paolo Giovio Archaeological Museum in Como. On the other hand, the piece of armor found in the pit of burial "III/1928" at Ca' Morta was most probably made in an Etruscan-style metal workshop. Carbon-14 dating places its manufacture around the middle of the 7th century B.C.[64]

Funerary urns[edit]

The funerary urn, which contains the ashes of the deceased, is a biconical artifact with a lid. Made of laminated bronze, it measures 30 cm in circumference at the opening, with two chips at the top. The urn was placed in the body of the funeral cult chariot.[6][69][52] The style and morphology of the cinerary vase are typical of the Golasecca "GIIB / GIIIA1" culture. During this period in the region around southern Lake Como,[notes 31] funerary rites involving cremation of the deceased seem to have been a constant practice. In particular, the Como pole/Ca' Morta necropolis, from the middle of the 2nd century B.C. onwards, was remarkably active in the production of so-called "biconical" urns,[notes 32] a craft legacy from Etruria.[52][69][24]

On the other hand, the cinerary container is decorated with ornamental hatch patterns created with a spatula by "hot incising" the metal material.[52][69][70]

Decorative objects[edit]

The pendeloque[edit]

From the sedimentary layers of the burial pit, a pendant was extracted,[notes 33] bearing witness to considerable material and technological wealth. Analyses of the physical and chemical properties of the materials making up the ornamental object unequivocally indicate that it is worked in gold and silver88,68,8. The ceremonial artefact is Etruscan in style68,86;[69] its manufacture is probably not entirely local.[69][71] It also features a seal, decorated with Etruscan-style convolutions.[52][72]

In addition to this remarkable piece of jewelry, excavation of the burial site revealed other ceremonial objects, such as "armilles"[notes 34] made of laminated bronze, and pearl earrings.[73][69][52][8]

Bracelets and necklaces[edit]

In addition to the pendant, teams of archaeologists excavating the Cà' Morta burial vault unearthed a number of ceremonial objects. Numerous serpentiform anklets and arm bracelets have been identified.[notes 35] Researchers have also identified large bronze necklaces of great craftsmanship.[73]

Other objects in the funerary instrumentum[edit]

The funerary furnishings of the Golaseccante pit also yielded a large number of Etruscan, Greek, "hallstatto-oriental" and Italic imports. Overall, these archaeological artefacts show great opulence due to their high quality of workmanship and craftsmanship, but also due to the materials used to create them. Among these mortuary offerings are an Etruscan phiale worked in gold;[74] numerous arched bronze fibulae with wide, spiral feet, belonging to the hallstatto-oriental culture; oenochoes, some with "Schnabelkanne "[notes 36][75][76][77][78][79] characteristics, and dishes of Greek import;[80] a bronze disc worked using a technique known as "repoussé", the outer part of which is ornamented.[6][73]

The North Italian tomb also contained a bronze stamnos. Identified as being of Etruscan-Villanovian origin, it is decorated with so-called "red-figure" motifs, and its use, given the chronological context of the Ca' Morta tomb, could be similar to that of a funerary urn.[81][73]

The burial vault also yielded an abundance of crockery, including various pieces of "incised sculpture" pottery.[73] Archaeologists have identified a large bronze situla with a lid from a Golaseccian metallurgist's workshop. The container was decorated with punched motifs.[notes 37][73]

In addition, the pit contained numerous sherds of Italic ceramics from Magna Graecia, featuring "black-figure" ornamentation.[6][73]

-

Stamnos of Etruscan origin

-

"Schnabelkanne" type oenochoe.

-

Serpentiform ceremonial bracelet

-

Fused bronze drinking vessel serving as a cinerary urn, "Golasecca II A" period.

-

Bronze fibula.

-

Corded cinerary cist, Golasecca II A period.

-

Bronze situla of the "Golasecca II A" type.

-

Ceramic from a Golaseccian workshop (second half of the 2nd century BC).

Reading and interpreting funerary furniture[edit]

Relations with the Celtic city of Vix/Mont Lassois[edit]

In 2013, a French team of archaeologists led by Bruno Chaume, director of the international Vix en Bourgogne program, was invited to the Paolo Giovio archaeological museum in Como to compare the results and analyses of the funerary trousseaux from the Vix and Ca' Morta burials. At first glance, the two funerary furnishings seem to have a great deal in common. For example, the two stamnos and the two large basins (made of bronze and of Etruscan origin) are virtually identical in terms of both their general shape and their method of manufacture.[82][83]

- The Hallstatt-type funerary chariot from the Vix tomb.

-

The "Hallstatt D" cultural facies chariot discovered in the Vix burial site.[notes 38]

The comparison of data collected by each research team focuses primarily on the chariots. Like the one in the Ca' Morta tomb, the Vix ceremonial chariot is found in the burial pit, in separate pieces, also worked in laminated bronze, with four wheels made of laminated bronze and oak wood.[84][85]

Initially, the two research teams concluded that there was a certain similarity in the physiognomies of the two chariots104. Further comparative analysis also revealed that the style and craft techniques required to produce many of the parts making up the ritual vehicles were, if not unicum,[notes 39] at least very similar (particularly with regard to chariot components such as balusters and body plates, hubs and hulls).[86] The ornamentation of the latter is considered to be very similar indeed.[6][84]

With regard to the Vix chariot, French archaeologist Stéphane Verger states the following:

"The only known similar vehicle is the one unearthed in the Ca' Morta chariot tomb in Como. - Stéphane Verger[81]

On the one hand, the deceased are both female; one is buried, the other cremated.[notes 40] Secondly, for each of the two archaeological facts, the funerary rites proceed from the same type of incorporation: the deceased rests inside the body of the chariot.[84][6][87] Because of the number of concordant clues and evidence, the two teams of archaeologists were able to establish a probable interaction between the territory of the Vix / Mont Lassois oppidum and that of the Ca' Morta comasque site.[84][6][88]

Relations with other Celtic cities such as Hochdorf[edit]

"There are many indications of contact with the Transalpine world, and it is from the Ca' Morta necropolis that one of the most recent four-wheeled funerary ceremonial chariots, dated to the 5th century BC, comes from. - Wenceslas Kruta[8]

Other teams of archaeologists have been able to identify numerous chariot tombs, geographically dispersed across the western half of the area covered by the Hallstatt civilization[notes 41] and belonging to territories 400 to 500 kilometers distant from Ca' Morta. These multiple occurrences of "chariot" funerary sites in the territory of the Celtic koinè[notes 42] present, like that of the Vix tomb, many elements in common with that of Ca' Morta. In addition to similarities in the style of ornamentation and the materials used for each component of the vehicle, specialists have also identified a deposition process identical to that used in all the listed cases. In fact, the deceased is regularly incorporated into the body of the chariot.[6][89] However, although the remains are always incorporated into the body of the float, there are some notable differences in the funeral ritual: the dead person is either cremated and placed in an urn or buried.[notes 43][89]

The 2012 exhumation of the Moutot funerary complex in Lavau, near Troyes, can be seen in this light.[90][91][notes 44]

Generally speaking, the archaeological finds at Ca' Morta, including the processional cart, are similar in nature and style to other items from Celtic burials and tombs of the Hallstattian period. Another series of chariot tombs can testify to these concordances: the Hochdorf tomb, the Reinheim tomb, the Kleinaspergle tomb or the Waldalgesheim tomb.[6][7][92][89]

In the particular case of Hochdorf, it is also remarkable that the ornamentation on the klinea (a type of ancient Greek bench)[notes 45][93][94][95] on which the deceased was laid, as well as the pendants with which his burial is associated, are typically Golaseccantes. This implies that they were made in a workshop located within the Golasecca archaeological facies area. Furthermore, the corded cists found in situ in the Hochdorf burial are considered to have come from the same workshop as those in the Ca' Morta tomb.[82][96]

Finally, all these burial sites generally display significant evidence suggesting a princely purpose.[6]

-

The Hochdorf burial mound.

-

The Hochdorf tank (Erdingen museum).

-

Bliesbruck-Reinheim archaeological park.

Taken together, these observations suggest direct links between the Comasque pole and sites across the Alps. However, these observations need to be qualified. On the basis of these data alone (the similarities observed), the phenomenon of long-distance relationships and the causes that might explain them remain probable but hypothetical. In any case, the physiognomic similarities between the Ca' Morta chariot and all the other chariots currently identified and catalogued do not constitute direct and indubitable proof of inter-territorial relations.[97]

In order to explain these obvious concordances between the Ca' Morta tomb and the burials of keltiké across the Alps,[notes 46][98][99] we need to focus on an important event in Comasque history. The Celtic invasions of northern Italy around 600 BC provide convincing evidence of the presence of Celtic elements in this northern Italian territory. This invasive phenomenon brought Celtic cultural and political components to the Golaseccian populations living in and around Como.[100][6][89][7]

Secondly, it is essential to consider the crossroads status of this Alpo-Lepontian region.[101][102][notes 47] At that time, the 10th century BC, the northern Italian region was an area of trade flows of international importance.[6][7][89] As such, in the historical framework of the Middle to Late Hallstatt period, river and land routes played a definite economic role.[6][7][89] In particular, the Comasque region appears to be one of the hubs of this territorial network.[6] The Como region's geostrategic position gave it an important commercial role, placing it on an essential communication route between northern Europe (Hallstatt civilization) and southern Europe (Italic civilization, Etruscan civilization and archaic Greek civilization). The crossroads position of the Comasque pole corroborates the hypothesis of contacts between princely cities such as Vix, Hochdorf and the other Celtic urban centers mentioned above125. Thus, the examples of the bronze "corded" cists and the chariot kline found at the Hochdorf burial site mentioned above corroborate the hypothesis of an export from the Golaseccian territory, and more specifically from the Como/Ca' Morta region.[6][7][103][89]

"This "Celtophony" of Como at the time of the Golasecca culture probably explains its development and wealth, as the agglomeration was the ideal intermediary in commercial traffic between the peninsula and the transalpine Celtic world."

- Wenceslas Kruta[34]

Relations with the civitas Bituriges Cubii and the Avaricum oppidum[edit]

-

Yèvre river, Cher tributary.[notes 48]

-

Panoramic view of the area around Bourges-Avaricum.[notes 49]

In the same context, numerous tombs found in Hallstattian-type necropolises in the Bourges/Avaricum agglomeration in the Cher region[notes 50] display funerary furnishings containing artifacts with Eastern Golaseccian facies.[notes 51][notes 52][104] These numerous material occurrences unquestionably confirm the existence of political, economic and cultural relations between the Bituriges Cubii urban hub of Avaricum and the princely site of Como/Ca' Morta.[105][106][107]

However, it is thought that these links went far beyond the strict political and economic framework.[108] In concrete terms, the two princely communities, stimulated by this process of international exchange, probably established numerous hospitality and even matrimonial relationships.[104] A large number of so-called "chariot graves" in the Avaricum oppidum agglomeration, and in particular the Dun-sur-Auron burial site, attest to the intrinsically intimate nature of these two princely cities. The burial site on the Dun road yielded bronze and gold ornaments for women, as well as archaeo-cultural pendants typical of "Golasecca IIC / Golasecca IIIA "[notes 53] in the 5th century BC. The elements making up the instrumentum of this cremation tomb suggest that the deceased was a woman, probably of North Italian stock with an Eastern Golaseccian cultural substratum[notes 54] and of princely social rank. She would have been the wife of a Bituriges Cubii war chief of notable hierarchical rank (probably a member of the aristocratic elite).[109][107] The archaeological material found in the Biturige burial pit bears striking similarities to that found in the Ca' Morta tomb.[110] In this light, the postulate that the two princely poles established privileged inter-ethnic relations[111] during the 5th century B.C. acquires explicit scope and credibility.[104][112][113]

In response to these observations and concerning the relationship between central Gaul and the northern Italian territory of Golasecca/Como, archaeologist Pierre-Yves Milcent argues:

"[...] the integration, with a few adaptations, of North-Italian funerary practices in Central Gaul implies the establishment of relations with Northern Italy that were not limited to the simple trafficking of luxury goods from one area to another. Individuals, men and women, moved to establish direct economic and cultural contacts, but also had to enter into relationships of hospitality, matrimonial, political and military alliances between the two regions."

- Pierre-Yves Milcent[114]

Geographical perspective[edit]

The following map[notes 55] lists and puts into perspective the main Late Hallstatt and Latenian A princely sites of the chariot tomb type that had commercial and political relations with the Golaseccian territory and the three main export centres of the period[notes 56]

Legend:

The red circles symbolize the two main Golaseccian poles and Mediolanum; Red triangles represent the main Celtic sites;

The three non-Celtic export hubs[notes 57] are symbolized by yellow circles.

The deceased figure in the Ca' Morta tomb[edit]

Social status and gender[edit]

The opulence of the instrumentum found on the "funerary scene" indicates that the cremated person was of high social status. In this light, it suggests a princely personality. In addition, ceremonial objects such as the minted pendant, bronze and silver necklaces and pearl earrings confirm that the deceased was a woman.[6][notes 58]

In this context, Italian archaeologist Raffaele Carlo de Marinis describes Golaseccante society in the 5th century BC:

"[...] the richest tombs at Golasecca are undoubtedly the female ones. This is due either to the history of discoveries, or more probably to a phenomenon similar to that which characterizes the Este culture, where the ostentation of wealth, at least in the funerary domain, now becomes a feminine prerogative." - Raffaele Carlo De Marinis[115]

Its ethnic origin and linguistic substratum[edit]

Strong archaeological evidence of the "Celtization" of the northern Italian territory is attributed, for the most archaic, to the Middle Bronze Age.[116][117] This unambiguously demonstrates the deep and ancient Celtic roots of the peoples settled in the Como / Cà'Morta area of influence.[118][117] However, this phenomenon is not marked by absolute continuity over time. Several waves of Celtic tribes migrated between the 15th and 2nd centuries BC.[119] These population movements gave rise to different cultural phases: the "Canegrate" culture[117]; the "Golasecca proto-culture "[117]; the Golasecca culture and, finally, the Middle and Late Latenian culture.[118][117] In addition, the interactions between the ancient peoples of Northern Italy and Etruria (and, to a lesser extent, Archaic Greece and the Italic ethnic groups)[118] should be emphasized. Certain contributions from these spheres of influence can be found within Celto-Italian communities. These contributions are present in many cultural fields. Linguistic, funerary, craft and ethnic domains were all strongly influenced by these non-Celtic civilizations.[118]

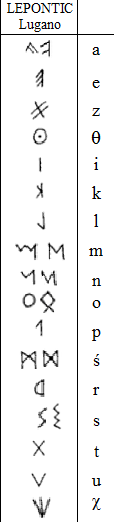

Genetic,[120] epigraphic,[42][121] and linguistic[122][42][123][124][125] (in the specific case of the Como / Ca' Morta cluster, the Lepontic)[126] analyses carried out on all the material occurrences collected on the Comasque territory, reveal that the tribe settled on the Como / Ca' Morta site during the First and Second Iron Ages, displays Orobian cultural and ethnic characteristics. The Orobians (also called "Orumbovii" or "Orobii" by the Romans), like the Insubres or Lepontians, were related to the Ligurians, and even to the Celto-Ligurians.[127] In fact, ancient literary sources[notes 59][128][129] supported by numerous archaeological findings, tend to confirm that this Celto-Italian people settled in a geographical area covering the mid-northern part of Italy.[notes 60] This territorial settlement is thought to have taken place between the end of the vii century BC and the beginning of the vi century BC.[127] Archaeological studies have made it possible to determine the exact location of the Orobii[130] within the Comascan territorial sphere during the whole of the First Iron Age, and have also confirmed the hypothesis that this tribe possessed a form of Golaseccante culture.[131][132][127]

- Main ethnic groups of the Golasecca, Hallstatt and La Tène cultures.

-

Main ethnic groups of the Golaseccian, Hallstattian and Latin civilizations.

In light of these elements, archaeological investigations unquestionably demonstrate that Celtic migrations, carried out in the life and fifth centuries BC, largely contributed to the ethnogenesis of the northern alpine tribes. In other words, this migratory phenomenon led to the emergence of new Celtic peoples in Lombardy and Piedmont during the Early and Middle Iron Ages. In particular, these events initiated the ethnogenesis of the Insubrious[133] and Orobian[134][133] populations, whose historiographical knowledge is affluent in archaeological evidence corroborated by a voluminous corpus of ancient bibliographical sources: in particular Book V by the Roman historian Titus Livius[135]; the work Geography[notes 61] by the Greek author Strabo[136]; the Historical Library (paragraph 24, Book V and paragraph 113, Book XIV) by the Greek historian Diodorus of Sicily;[137][138] the Geographical Guide by the historian Ptolemy;[139][140] or the Roman History (Book V, paragraphs 33 to 35) by the Roman thinker Appian.[141] These testimonies confirm their Celtic origin.[142][127]

- Historical maps of the tribes settled in northern Italy: Cisalpine Gaul as seen by the Romans.

-

Historical map of Gallia Cisalpina.[notes 62]

-

Main Celtic peoples of the Italian peninsula.

From this perspective, these arguments demonstrate that the various ethnic groups making up the population located in the Golaseccian[notes 64] geographical area share an undeniable Celtic genetic capital and cultural, linguistic[notes 65][143] and artisanal determinant.[142][144][145][146][147]

In a speech at the Collège de France, historian Daniele Vitali concludes his thesis on the role and testimonial value of the Prestino inscription (epigraphy written in Lepontic), at that time (5th century BC) and in that precise place:

"From the point of view of a sociological interpetation, this "public" inscription, in a monumental context intended for the civic community of Como, gives the idea of the importance of the "Celtic" language as a means of communication for the Celtic-speaking (and literate) individuals of this "city" at the beginning of the 5th century B.C." - Daniele Vitali[148]

- Mother language of the Princess of Ca' Morta.

-

Language groups on the Italian peninsula.[notes 66]

Other excavations at the Ca' Morta necropolis[edit]

Within the Ca' Morta necropolis, two other tombs, remarkable for the archaeological typology of their funerary furnishings, have received particular attention. These were discovered and studied between 1955 and 1965:[12]

- in tomb no. 162, "wide-footed" fibulae[notes 67] twisted and decorated with incised dots and imported Greek ceramics were unearthed.[149][150][151] A clear link has been established with other funerary sites in northern and central Italy (notably in Tuscany, Veneto, Lazio and Umbria) dating from around 1070 to 940 B.C.;[152]

- Tomb no. 14 contains mainly bronze "Schnabelkanne" type beaker ware, probably of Etruscan origin, and corded cistas of Greek origin. The latter are made of ceramic and feature "black-figure" motifs.[152][12]

- Paolo Giovio Archaeological Museum, Como

-

Museum courtyard.[notes 68]

The main architect of the archaeological research[notes 69] that identified and formalized the Ca' Morta necropolis[12][13] was the Italian archaeologist Ferrante Rittatore Vonwiller (1919 - 1976). In the 1970s, he extended his field of study, uncovering burials whose chrono-cultural facies showed notable differences, particularly with regard to the symposia extracted from their funerary context. After examination and expert appraisal, these finds were found to belong to the Late Bronze Age.[12] The archaeologist was thus able to correlate them with a funerary establishment predating that of the Ca' Morta tomb, and attribute them to the chrono-cultural period characteristic of the central-septentrional territory of Lombardy (Comascan region) from the 11th to the 9th century BC, in other words, the Canegrate culture.[12]

In the mid-1980s, and again in the early 1990s, archaeological excavations resumed, uncovering burials attributed to the Early and Late Iron Age ("Hallstatt D" and "La Tène A, B").

- Excavation of burial site no. 113 revealed an extensive sympósion of Etruscan ceramics, bucchero nero and terracotta ware. The extraction and examination of this instrumentum reveal privileged commercial relations between Etruria Padana and the site to which the Comascan necropolis belongs.[15]

- Graves no. 114 and "I/1930" each yielded a stamnoid situla. Both religious and funerary vessels, made of bronze, are ovoid in shape. In addition, they feature an imposing circumference.[15]

- Excavations adjacent to burial site no. 302 produced corroded remains of a biconical urn, as well as fragments of fibulae. Archaeological expertise revealed that all of these elements were typically Etruscan-Padan craftsmanship.[14]

- Investigations of tomb no. 16 led to the discovery of an abundant funerary trousseau consisting of an urn, a "twisted arch" fibula (also known as a "ribbed" fibula),[notes 70] a necklace with a pendant, and a ceramic dish with a 5.8-centimeter-high foot.[17]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Surface area of the tomb alone, without the tumulus.

- ^ This is a piece of the armor of both hallstatto-oriental and proto-etruscan (i.e. Villanovian) craftsmanship. This type of helmet refers to a series of 28 bronze helmets dating back to the 5th century B.C. and found in 1811 in the vicinity of Negova (Negau in German) in Slovenia.

- ^ This is the museum where the processional float from the "tomb III/1928" has been reconstructed.

- ^ The museum currently houses and exhibits some of the objects unearthed in the Ca' Morta tomb.

- ^ Depending on the country and the language used, specialists also accept the names "Tomba di Cà' Morta", "Tomba di Ca'Morta" and "Casa di Ca' Morta".

- ^ Or "casa dei morti", meaning "house of the dead" in Venetian.

- ^ Comasque", or more rarely "Comien", is the local term for Como.

- ^ The number III indicates that this is the third tomb uncovered at the Ca' Morta necropolis, and the number "1928" refers to the year of its discovery.

- ^ Archaeologists have found that the earliest burial structures date back to the Late Bronze Age (11th - 10th century BC). Further investigations in the 1980s and early 1990s revealed graves dating from the Early and Late Iron Ages ("Hallstatt D" and "La Tène A, B").

- ^ In archaeological terms, as defined by archaeologist P. Moinat, "viaticum" is the set of objects associated with funerary and eschatological practices18. For researcher and historian Raphaël Angevin, "viaticum" is the equivalent of funerary furniture19. According to archaeologist Luc Baray, viaticum is the set of material deposits of funerary objects, distinct from the personal objects of the deceased20. Conversely, in the field of religion, "viaticum" is a "Catholic sacrament, an extreme unction "21.

- ^ More precisely, from around the 13th century BC to the 10th century BC. - In this case, the founding event of this second floor is attributed to the "Canegrate" chronological period.

- ^ That is, places dedicated to religious rites, or to political power.

- ^ This is a small hill at an altitude of 1,350 metres, located on the southern outskirts of Como. The architectural remains were incorporated into the sedimentary stratigraphic layers, and located on the adret of the valley.

- ^ Como's protohistoric urban center.

- ^ The latter is located in the Albate comasque district, where the Ca' Morta burial site was unearthed.

- ^ This map shows the location of the Comascan suburb of Prestino di Como, where remains of settlements, an epigraphic inscription in Lepontic, coins from Populonia and a protohistoric city in Etruria Padana have been discovered. The Albate district lies some 20 km to the east of the latter.

- ^ This is a process of accretion of proto-urban sites developing within the same territorial zone. This phenomenon contributes to the concentration of native populations and, ultimately, to the foundation of an ancient city.

- ^ This is an epigraphic dedication uncovered in locare on an ancient architectural structure (probably a step) in the Comascan suburb of Prestino di Como. The latter is located in the western part of the Comascan agglomeration. It has been confirmed that this was written in Lepontic script. It has also been confirmed that this Celtic dedication is chronologically the oldest recorded in Northern Italy.

- ^ And consequently to the growth of Celtic "koinè".

- ^ These ancient bibliographical references, mentioning Celtic settlement at this comasque site, appear in Book XXXIII, paragraph 36, of the Ab Urbe condita libri (Roman History) by the Roman historian Titus Livius; in Book III, paragraph 124, of the Histoire naturelle by the Cômois Pliny the Elder ; in Book IV, chapter 3, of the collection Geography, manuscript by the Greek Strabo; in passage 29 of the biographical work Caesar, written by Plutarch; and, finally, in Book III, chapter 1, of the collection Geography, written by the Greek astronomer and astrologer Ptolemy.

- ^ An epigraphic inscription in Lepontic script discovered in a stepped structure, it is attributed to the turn of the 5th and 4th centuries B.C. (around 500 B.C.).

- ^ This was unearthed on the Prestino di Como hillside, not far from the Cà' Morta tomb.

- ^ In other words, a group of dwellings spaced significantly apart from one another, and whose number is small. More concretely, a proto-urban grouping cannot be considered a city.

- ^ In other words, the Celtic military confederation led by the warlord Brennos, who marched on Delphi and thus previously on Northern Italy, between 299 and 297 BC.

- ^ In other words, the cultural facies specific to the geographical area of the eastern half of Golasecca. This more or less corresponds to the present-day geographical area of central eastern and northern Lombardy, of which the urban site of Como is the active political, economic and cultural center. Moreover, this so-called "eastern" facies is the result of a later development than the "western type", or "Golasecca type 2".

- ^ In other words, all the objects found in the tomb.

- ^ This is a blacksmith's process of cold working a sheet of metal upside down with a spatula, to bring out a motif either as an icon or as an ornament.

- ^ In other words, a type of vase used for drinking, such as wine. It generally has a wide upper circumference and a shallow depth.

- ^ The figures are painted red on a black background.

- ^ In other words, a helmet with a circular base and a conical upper part. The first discovery of this type of artifact, in 1811, was made in the vicinity of Negau, Germany. More recent discoveries have confirmed that this type of armor is based on a craft concept that was simultaneously proto-Etruscan (Villanovian culture) in the 7th and 6th centuries BC, and hallstatto-Oriental.

- ^ Like most of the Golaseccian space.

- ^ This type of urn features a double cone-shaped narrowing of the upper and lower parts.

- ^ In other words, a kind of pendant.

- ^ In other words, serpentine and/or spiral bracelets.

- ^ In other words, spiral-shaped.

- ^ This typology refers to a unicum (or homogeneous set) of bronze oenochoes with a raised spout. Most pitchers of this type have been found in an area encompassing Switzerland and southern Germany. Other utensils of this type have been found in Gaul, Padanian Etruria and in the Celto-Italian territories of the Golaseccante culture. In 1914, the French archaeologist Joseph Déchelette (1862 - 1914) published the very first detailed study and listing of these oenochoes.

- ^ An identical lid, dated to the 2nd century B.C., was discovered in the tomb at Trezzo sull'Adda. This suggests an identical creation and therefore a common workshop99 dating from the Golasecca 2b period.

- ^ Located in the urban city of the same name, in the Côte-d'Or department. The archaeo-funerary artifact is currently on display at the Musée Historique de Châtillon-sur-Seine.

- ^ In other words, identical in appearance and procedure.

- ^ In both cases, they rest in the tank body.

- ^ The Hallstatt civilization is an ancient culture specific to the Celts of western and central Europe. Its chronology corresponds, more or less, to the 1st European Iron Age.

- ^ Such as the float found under the La Motte tumulus, the Sainte-Colombe float, or the Kitzingen-Rippendorf float.

- ^ Which is incorporated into the tank body.

- ^ However, although the funerary furnishings of the two burials at Lavau and Ca' Morta bear certain similarities, archaeologists have found no obvious link between the Gaulish princely site and the Golaseccian one.

- ^ In this particular case, at Hochdorf, it's a bench from a Celtic workshop, intended as a deathbed for the deceased.

- ^ According to several ancient authors, including the Greek Poseidonios of Apamea and Appian, the keltiké grouped together all the peoples of Celtic culture and language in the Iron Age120,121.

- ^ According to several ancient authors, including the Greek Poseidonios of Apamea and Appian, the keltiké grouped together all the peoples of Celtic culture and language in the Iron Age.

- ^ This river flows through the heart of downtown Bourges, in the Cher department. The meandering river forms marshy areas that would have favored the castrametation (strategic siting choice) of the final Hallstattian oppidum of Avaricum.

- ^ In other words, this is the ancient "Final Hallstattian" oppidum of Avaricum, the main political, religious and economic hub of the civitas of the Bituriges Cubii.

- ^ Necropolises indexed to the 6th century BC, life century BC and 5th century BC and attributed to the "civitas" of the biturii cubi.

- ^ In other words, the Golasecca culture centered on the protohistoric pole of Como-Ca' Morta.

- ^ These are mainly manufactured products such as laminated bronze situlae with riveted bellies, ceremonial clothing, bronze "curved foot" and "spiral head" fibulae, and painted ceramic tableware.

- ^ See cultural timeline.

- ^ In other words, the geo-cultural context centered on the politico-economic urban hub of Como / Cà'Morta / Prestino di Como.

- ^ Main Celtic sites and export hubs linked to the Golaseccian territory.

- ^ That is to say: Massilia; Etruria, represented essentially by Bologna; and archaic Greece.

- ^ The Phocaean city of Massilia; Etruria; and archaic Greece/Athens.

- ^ In other words, all the small occurrences or facts that make up the archaeological material of an archaeological site, or "small furniture".

- ^ Among others, Pliny the Elder's Natural History, Book III, paragraphs 124 and 125.

- ^ This territory roughly corresponds to the present-day regions of Como and its lake, Bergamo (whose capital is the oppidum) and the valleys adjacent to these two urban areas.

- ^ In particular, passage 1.1 of Book IV.

- ^ This historio-geographic document shows the Orumbovii located on the north-northern periphery of the spatial area shown in red on the map, i.e. south of Lake Como.

- ^ Also known as the "Lugano alphabet", it is based, among other occurrences, on the epigraphic inscription, the Prestino inscription, unearthed on a hillside in the Comascan suburb of Prestino di Como, not far from the western outskirts of the city of Como, the Swiss border town of Lugano, in Ticino.

- ^ In particular, the two major hubs are the shores of the Ticino and the southern part of Lake Como / Ca' Morta site.

- ^ In this case, Lepontique.

- ^ The geographical area of Ca' Morta, the protohistoric princely site of Como, is part of the Italian territory with a Celtic linguistic substratum.

- ^ In other words, ornamental objects whose second part, the foot (as opposed to the head), is significantly wider than fibulae with thread-like feet.

- ^ The archaeological museum is located in a suburb on the outskirts of Como, in the Italian province of Lombardy. The monument to ancient Celto-Italian artefacts and remains currently houses and exhibits artefacts unearthed in the tomb and other finds from this funerary complex (including, in particular, finds produced by archaeologist Ferrante Rittatore Vonwiller).

- ^ But also the "father" of these discoveries.

- ^ The ceremonial object is listed under no. 378. In addition, the most recent archaeological data tends to confirm that this type of "ribbed" fibula is characteristic of the "Golasecca IA and IB" facies (i.e.: 9th century BC / 7th century BC). The numerous finds of this type of funerary element in a geographical area stretching from the Padana plain to the Celtic territories beyond the Alps suggest a wide commercial distribution of this type of object.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Jully (1982, p. 82)

- ^ a b Defente (2003, pp. 103–108)

- ^ a b c Bergonzi, Giovanna; Lucentini, Nora (1981). L' area a Sud-Est delle Alpi e l'Italia del Nord intorno al V secolo A.C. Studi di protostoria adriatica / a cura di R. Peroni. Roma: L'Erma di Bretschneider. ISBN 978-88-7062-498-4.

- ^ a b Defente (2003, p. 103)

- ^ "Studiosi francesi alla ricerca di nuovi legami tra il carro della Ca' Morta e quello della principessa di Vix". www.archeologia.com. Retrieved 2024-06-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 57–58)

- ^ a b c d e f Brun (1987, p. 81)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Kruta (2000, p. 144)

- ^ "Way: Via Giovanni Baserga (33438184)". OpenStreetMap. 2020-03-16. Retrieved 2024-06-13.

- ^ a b c Tardi (2007, p. 75)

- ^ Catacchio, Nuccia Negroni. "Ferrante Rittatore Vonwiller (1919-1976). L'archeologia come intuizione e come passione". Academia.edu.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rittatore Vonwiller (1966, pp. 1 à 176)

- ^ a b Roncoroni, Francesca (2009-01-01). "I materiali metallici e ceramici databili tra il Bronzo Recente e l'età del Ferro". Tremona - Castello. Dal V Millennio A.C. Al XIII Secolo D.C.

- ^ a b Casini, Stefania (2014-01-01). "Indices de mobilité au Premier Age du fer, au sud et au nord des Alpes". D. VITALI (a cura di), Les Celtes et le Nord de l’Italie / I Celti e l’Italia del Nord, Vérone (17-20 mai 2012), XXXVIe Colloque International de l’Association Française pour l’étude de l’Age du Fer.

- ^ a b c Casini, Stefania (2014-01-01). "Indices de mobilité au Premier Age du fer, au sud et au nord des Alpes". D. VITALI (a cura di), Les Celtes et le Nord de l’Italie / I Celti e l’Italia del Nord, Vérone (17-20 mai 2012), XXXVIe Colloque International de l’Association Française pour l’étude de l’Age du Fer.

- ^ Casini, Stefania (2014-01-01). "Indices de mobilité au Premier Age du fer, au sud et au nord des Alpes". D. VITALI (a cura di), Les Celtes et le Nord de l’Italie / I Celti e l’Italia del Nord, Vérone (17-20 mai 2012), XXXVIe Colloque International de l’Association Française pour l’étude de l’Age du Fer.

- ^ a b Marinis, Raffaele Carlo DE. "De Marinis Annali Orvieto XV 2008". Academia.edu.

- ^ Masi, Patrizia von Eles (1986). Le fibule dell'Italia settentrionale (in Italian). C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-09708-9.

- ^ a b Brun (1987, p. 80)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 139–151)

- ^ a b Chevallier, Raymond (1983). "La romanisation de la Celtique du Pô. Essai d'histoire provinciale". Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises d'Athènes et de Rome. 249 (1): 0. doi:10.3406/befar.1983.1214. ISBN 2-7283-0048-8.

- ^ a b Tardi et al. (2007, pp. 75–76)

- ^ Tardi et al (2007, pp. 75–77, 80–88, 90.)

- ^ a b Lorre & Cicolani (2009, p. 40)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 92–93)

- ^ a b c Kruta (2000, pp. XIII, 144, 553–554)

- ^ Tardi et al (2007, pp. 80–88)

- ^ Tardi et al. (2007, pp. 77–79, 81–85, 90–95)

- ^ Lejeune & Pouilloux et Solier (1988, pp. 2–3, 704–705)

- ^ Stifter (2012, p. 29)

- ^ Lambert (2003, pp. 21, 79)

- ^ "Celtique, écritures - Exemples d'écritures". lila.sns.it (in French). Retrieved 2024-06-14.

- ^ Delamarre (2003, pp. 54–56)

- ^ a b c Kruta (2000, p. 554)

- ^ a b c d e Buchsenschutz (2015, p. 93)

- ^ Fichtl (2005, p. 149)

- ^ a b Tardi et al (2007, pp. 81, 87, 90–95)

- ^ a b Vitali (2007, pp. 72–73)

- ^ Irollo (2010, pp. 58, 72)

- ^ Irollo (2010, p. 72)

- ^ Kruta (2000, pp. XIV, 144–145, 553–554)

- ^ a b c d e Kruta (2000, p. XIV, 144-145)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, p. 91)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 91, 93)

- ^ Lorre & Cicolani 2009, p. 41-42, 60.

- ^ Vitali 2007, p. 29, 31-32, 61.

- ^ Brun 1987, p. 184-185.

- ^ Buchsenschutz 2015, p. 92-93.

- ^ a b Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 40, 42)

- ^ a b Garcia (2014, pp. 84–85)

- ^ Brun (1987, pp. 180, 184–185)

- ^ a b c d e f g Sabatino Moscati (1995, pp. 267–268)

- ^ Garcia (2014, p. 85)

- ^ Brun (1987, pp. 180–182)

- ^ a b Sabatino Moscati (1995, p. 267)

- ^ a b c Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 59–60)

- ^ Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 48, 51–53, 102)

- ^ a b c Brun (1987, pp. 80–81)

- ^ a b c d Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 48, 51–53)

- ^ Lorre & Cicolani (2009, p. 102)

- ^ Sabatino Moscati (1995, pp. 268–269)

- ^ Marinis, Raffaele Carlo DE. "Tecnologia economia e scambi". Academia.edu.

- ^ "Studiosi francesi alla ricerca di nuovi legami tra il carro della Ca' Morta e quello della principessa di Vix". www.archeologia.com. Retrieved 2024-06-15.

- ^ a b c d Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 63–64, 143)

- ^ Feugère, Michel; Freises, André (1994). "Un casque étrusque du Ve siècle av. notre ère trouvé en mer près d'Agde (Hérault)". Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise. 27 (1): 1–7. doi:10.3406/ran.1994.1442.

- ^ Colloque, Association francaise pour l'étude de l'âge du fer (2007). L'âge du fer dans l'arc jurassien et ses marges: dépôts, lieux sacrés et territorialité à l'âge du fer : actes du XXIXe colloque international de l'AFEAF, Bienne, canton de Berne, Suisse, 5-8 mai 2005 (in French). Presses Univ. Franche-Comté. ISBN 978-2-84867-201-4.

- ^ D’Ercole, Maria Cecilia (2002), "V. Les métaux", Importuosa Italiae litora : Paysage et échanges dans l'Adriatique méridionale à l'époque archaïque, Études (in French), Naples: Publications du Centre Jean Bérard, pp. 189–270, ISBN 978-2-918887-62-1, retrieved 2024-06-17

- ^ Hubert, Henri (2012-12-01). Les Celtes (in French). ALBIN MICHEL. ISBN 978-2-226-23434-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Postel (2010, pp. 60–62)

- ^ Lorre & Cicolani (2009)

- ^ Lorre & Cicolani (2009, p. 48)

- ^ Postel (2010, pp. 59–62)

- ^ a b c d e f g Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 67–68)

- ^ Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 69, 143)

- ^ Bouloumié, Bernard (1973). "Les œnochoés en bronze du type "Schnabelkanne" en Italie". Publications de l'École Française de Rome. 15 (1): 0.

- ^ Gran Aymerich, José-Maria-Jean (1995). "Le bucchero et les vases métalliques". Revue des Études Anciennes. 97 (1): 45–76. doi:10.3406/rea.1995.4607.

- ^ Stürmer, Veit (1985). "Schnabelkannen : eine Studie zur darstellenden Kunst in der minoisch-mykenischen Kultur". Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique. 11 (1): 119–134. doi:10.3406/bch.1985.5273.

- ^ Briquel, Dominique; Landes, Christian (2005). "Une inscription étrusque retrouvée dans les collections de la Société archéologique de Montpellier (note d'information)". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 149 (1): 7–26. doi:10.3406/crai.2005.22826.

- ^ "Artefacts - Cruche de type Schnabelkanne (CRU-2011)". artefacts.mom.fr. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ Lorre & Cicolani (2009, p. 70)

- ^ a b Verger (2003, p. 592)

- ^ a b Verger (2003, p. 587)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 50, 65, 90, 129, 140, 142, 379)

- ^ a b c d Högberg, J.; Orrenius, S.; O'Brien, P. J. (1975-11-15). "Further studies on lipid-peroxide formation in isolated hepatocytes". European Journal of Biochemistry. 59 (2): 449–455. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02473.x. ISSN 0014-2956. PMID 1255.

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 142, 145)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, p. 379)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 240–241, 259.)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, p. 149)

- ^ a b c d e f g Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 83, 97–98, 100)

- ^ Dupuis (2015, pp. 272–274)

- ^ "Actualité | Découverte d'une nouvelle tombe princière du Ve siècle avant notre ère". Inrap (in French). 2015-03-05. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ Vitali (2007, pp. 63–64)

- ^ Lambrinoudakis, Vassilis; Balty, Jean Charles (2004). Thesaurus Cultus Et Rituum Antiquorum (ThesCRA).: Abbreviations (in French). Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-787-0.

- ^ Buchsenschutz, Olivier (2007-05-02). Les Celtes: De l'âge du Fer (in French). Armand Colin. ISBN 978-2-200-35600-2.

- ^ Mohen, Jean-Pierre (1995-09-06). Rites de l'au-delà (Les) (in French). Odile Jacob. ISBN 978-2-7381-0324-6.

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 109–110)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 99–101)

- ^ Lefèvre, André (1895). "Les Celtes orientaux. Hyperboréens, Celtes, Galates, Galli". Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris. 6 (1): 330–351. doi:10.3406/bmsap.1895.5590.

- ^ Hofeneder, Andreas. "Appians Keltiké". Academia.edu.

- ^ Bocquet, Aimé (1989). "Cohérence entre les dates dendrochronologiques alpines au Bronze final et la chronologie typologique italique". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française. 86 (10): 334–339. doi:10.3406/bspf.1989.9884.

- ^ "L'épontines (Alpes) - 10020 - L'encyclopodie - L'Arbre Celtique". www.arbre-celtique.com. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ Kürschner, Iris; Haas, Dieter (2015-04-08). GTA Grande Traversata delle Alpi: À travers le Piémont jusqu´à la Méditerranée. 65 étapes. Avec dates GPS (in French). Bergverlag Rother GmbH. ISBN 978-3-7633-4944-9.

- ^ Verger (2003, p. 597)

- ^ a b c Milcent (2007, pp. 222–223)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 146, 150)

- ^ Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 57–58, 141–142)

- ^ a b Milcent (2007, pp. 258, 293–295)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 146, 151)

- ^ Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 143, 159)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 143–144)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, p. 77)

- ^ Milcent (2007, p. 330)

- ^ Milcent (2007, pp. 33–35)

- ^ Lorre, Cicolani & Milcent (2010, p. 142)

- ^ Lorre, Cicolani & De Marinis (2012, p. 50)

- ^ Vitali (2007, pp. 68–69)

- ^ a b c d e Kruta-Poppi, Luana (1995). "Protohistoire italique". Annuaires de l'École pratique des hautes études. 126 (9): 29.

- ^ a b c d Vitali (2007, pp. 67–69, 71–72)

- ^ Vitali (2007, pp. 71–72)

- ^ Vitali (2007, pp. 69–70)

- ^ Vitali (2007, pp. 72–73)

- ^ Vitali (2007, p. 66)

- ^ Lambert (2003, p. 21)

- ^ Delamarre (2003, p. 56)

- ^ Lejeune, Pouilloux & Solier (1988, pp. 2–3)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, p. 78)

- ^ a b c d Lorre & Cicolani (2009, pp. 66–68, 70–75)

- ^ Vitali (2007, p. 21)

- ^ Kruta (2000, p. 765)

- ^ Vitali (2007, pp. 70–71)

- ^ Kruta (2000, pp. 156–163)

- ^ Kruta (2000, pp. 156–163)

- ^ a b Kruta (2000, p. 13)

- ^ Kruta (2000, p. 12)

- ^ Vitali (2007, p. 18)

- ^ Kruta (2000, p. 17)

- ^ Kruta (2000, p. 16)

- ^ Vitali (2007, p. 19)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, p. 6)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, p. 6)

- ^ Vitali (2007, p. 20)

- ^ a b Cunliffe (2009, pp. 11–13)

- ^ Buchsenschutz (2015, pp. 54, 57, 68–69, 93, 320)

- ^ Högberg, J.; Orrenius, S.; O'Brien, P. J. (1975-11-15). "Further studies on lipid-peroxide formation in isolated hepatocytes". European Journal of Biochemistry. 59 (2): 449–455. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02473.x. ISSN 0014-2956. PMID 1255.

- ^ Högberg, J.; Orrenius, S.; O'Brien, P. J. (1975-11-15). "Further studies on lipid-peroxide formation in isolated hepatocytes". European Journal of Biochemistry. 59 (2): 449–455. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02473.x. ISSN 0014-2956. PMID 1255.

- ^ Vitali (2007, p. 63)

- ^ Högberg, J.; Orrenius, S.; O'Brien, P. J. (1975-11-15). "Further studies on lipid-peroxide formation in isolated hepatocytes". European Journal of Biochemistry. 59 (2): 449–455. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02473.x. ISSN 0014-2956. PMID 1255.

- ^ Vitali (2007, p. 62)

- ^ Otte, Marcel (2008-11-18). La protohistoire (in French). De Boeck Supérieur. ISBN 978-2-8041-5923-8.

- ^ Fauduet, Isabelle (1979). "Notes sur la technique des fibules gallo-romaines « à queue de paon »". Revue archéologique du Centre de la France. 18 (3): 149–152. doi:10.3406/racf.1979.2252.

- ^ Dilly, Georges (1978). "Les fibules gallo-romaines du Musée de Picardie". Revue archéologique de Picardie. 5 (1): 157–175. doi:10.3406/pica.1978.1266.

- ^ a b Bocquet, Aimé (1989). "Cohérence entre les dates dendrochronologiques alpines au Bronze final et la chronologie typologique italique". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française. 86 (10): 334–339. doi:10.3406/bspf.1989.9884.

Bibliography[edit]

- Batardy, Christophe; Buchsenschutz, Olivier; Dumasy, Françoise (2001). Le Berry Antique: Atlas 2000, vol. 21, Tours, FERAC, coll. « Supplément à la Revue archéologique du centre de la France ». FERAC. ISBN 2-913272-05-3.

- Brun, Patrice (1987). Princes et princesses de la Celtique: le premier âge du fer en Europe (850-450 av. J.-C.) coll. « Hespérides ». Paris: Errance. ISBN 2-903442-46-0.

- Buchsenschutz (dir.), Olivier (2015). L'Europe celtique à l'âge du fer : viiie – ier siècles, coll. « Nouvelle Clio ». Paris: Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-057756-0. ISSN 0768-2379.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2009). Histoire des Celtes: de l'âge du bronze aux migrations. L'Archéologue. ISSN 1255-5932.

- Defente, Virginie (2003). Les Celtes en Italie du nord : Piémont oriental, Lombardie, Vénétie, du vie siècle au iiie siècle av. J.-C., Rome, École française de Rome, coll. « Collection de l'École française de Rome ». Ecole française de Rome. ISBN 2-7283-0607-9.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise : une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental, coll. « Hespérides ». Paris: Errance. ISBN 2-87772-237-6.

- Dupuis, Bastien (2015). " La tombe princière du ve siècle avant notre ère de Lavau « ZAC du Moutot » (Aube) ". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française.

- Fichtl, Stephan (2005). La ville celtique : les oppida de 150 av. J.-C. à 15 apr. J.-C., Paris, coll. « Hespérides / histoire-archéologie ». Errance. ISBN 2-87772-307-0.

- Garcia, Dominique (2014). La Celtique méditerranéenne: habitats et sociétés en Languedoc et en Provence (viiie – iie siècle av. J.-C.), Arles, Errance, coll. « Les Hespérides ». Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-562-0.

- Gomez De Soto, José; Milcent, Pierre-Yves (2003). " La France du Centre aux Pyrénées (Aquitaine, Centre, Limousin, Midi-Pyrénées, Poitou-Charentes) : cultes et sanctuaires en France à l'âge du fer ". Gallia.

- Irollo, Jean-Marc (2010). Histoire des Étrusques: l'antique civilisation toscane, viiie – ier siècle av. J.-C., coll. « Tempus ». Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-02837-4.

- Jully, Jean-Jacques (1982). Céramiques grecques ou de type grec & autres céramiques en Languedoc méditerranéen, Roussillon et Catalogne : VIIe-IVe s. avant notre ère, et leur contexte socio-culturel, Partie. Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté.

- Kruta, Venceslas (2000). Les Celtes, histoire et dictionnaire : des origines à la romanisation et au christianisme, Paris, coll. « Bouquins ». Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-05690-6.

- Kruta-Poppi, Luana (1993). « Protohistoire italique », École pratique des hautes études/Section des sciences historiques et philologiques.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (2003). La langue gauloise: description linguistique, commentaire d'inscriptions choisies, Paris, coll. « Hespérides ». Errance. ISBN 2-87772-224-4.

- Jeune, Michel (1984). « Deux inscriptions magiques gauloises: plomb de Chamalières; plomb du Larzac », Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. ISSN 1969-6663.

- Lejeune, Michel (1988). Jean Pouilloux et Yves Solier, « Étrusque et ionien archaïques sur un plomb de Pech Maho (Aude) ». Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise. doi:10.3406/ran.1988.1323. ISSN 2117-5683.

- Lorre, Christine; Cicolani, Veronica (2009). et , Golasecca: du commerce et des hommes à l'âge du fer (viiie – ve siècle av. J.-C.). Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. ISBN 978-2-7118-5675-6.

- Megaw, Ruth; Megaw, John (2005). Art de la Celtique : des origines au Livre de Kells. Paris: Errance. ISBN 2-87772-305-4.

- Milcent (dir.), Pierre-Yves (2007). Bourges-Avaricum, un centre proto-urbain celtique du Ve s. av. J.-C. : les fouilles du quartier de Saint-Martin-des-Champs et les découvertes des établissements militaires, vol. 1&2, Bourges, Ville de Bourges, Service d'archéologie municipal, coll. « Bituriga / monographie ». ISBN 978-2-9514097-7-4.

- Moscati, Sabatino (1995). Les Italiques: l'art au temps des Étrusques, Paris, coll. « Arts et cultures ». L'Aventurine. ISBN 2-84190-008-8.

- Postel, Brigitte (2010). " Golasecca: Celtes du nord de l'Italie ". Archéologia. ISSN 0570-6270.

- Stifter, David (2012). Celtic in Northern Italy: Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish. rootsofeurope.ku.dk.

- Rittatore Vonwiller, Ferrante (1966). La necropoli preromana della Ca' Morta: (scavi 1955-1965), Côme. Noseda.

- Tarditi, Chiara (2007). Dalla Grecia all'Europa: la circolazione di beni di lusso e di modelli culturali nel VIe V secolo a.C (atti della giornata di studi), Milan, Vita e Pensiero. Vita e Pensiero. ISBN 978-88-343-1494-4.

- Tarditi, Angelo Eugenio Fossati, Raphaele Carlo De Marinis, Stephania Casini et Piera Melli, Chiara (2006). Dalla Grecia all'Europa : atti della giornata di studi (Brescia, Università cattolica, 3 marzo 2006) : la circolazione di beni di lusso e di modelli culturali nel VI e V secolo a.C :, Brescia, Vita e Pensiero.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Verger, Stéphane (2003). " Qui était la Dame de Vix ? », dans Mireille Cébeillac-Gervasoni et Laurent Lamoine, Les élites et leurs facettes : les élites locales dans le monde hellénistique et romain, Clermont-Ferrand, coll. « Erga ". Presses universitaires Blaise Pascal. ISBN 2-84516-228-6.

- Vitali, Daniel (2007). Les Celtes d'Italie, Paris, coll. « Leçons inaugurales du Collège de France » (no 189). Collège de France/Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-63289-6.

- Vitali, Daniel (2013). Les Celtes: trésors d'une civilisation ancienne, Verceil. White star. ISBN 978-88-6112-467-7.

![John Baserga Street.[notes 15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/67/Via_Giovanni_Baserga%2C_C%C3%B4me.jpg/295px-Via_Giovanni_Baserga%2C_C%C3%B4me.jpg)

![Albate district.[notes 16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/04/Prestino_di_Como%2C_C%C3%B4me%2C_Italie.jpg/289px-Prestino_di_Como%2C_C%C3%B4me%2C_Italie.jpg)

![Prestino's registration[notes 21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/Lepontic_inscription_03.jpg/1950px-Lepontic_inscription_03.jpg)

![Typical coin of Populonia minted "with the lion", issued during the 5th century B.C.[notes 22]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Polulonia_25_asses_74000022.jpg/220px-Polulonia_25_asses_74000022.jpg)

![The "Hallstatt D" cultural facies chariot discovered in the Vix burial site.[notes 38]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fb/Vix01.JPG/214px-Vix01.JPG)

![Yèvre river, Cher tributary.[notes 48]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1f/Y%C3%A8vre_Bourges.JPG/240px-Y%C3%A8vre_Bourges.JPG)

![Panoramic view of the area around Bourges-Avaricum.[notes 49]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Bourges_2.JPG/271px-Bourges_2.JPG)

![Historical map of Gallia Cisalpina.[notes 62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f7/Gallia_cisalpina_-_Shepherd_png.png/352px-Gallia_cisalpina_-_Shepherd_png.png)

![Language groups on the Italian peninsula.[notes 66]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Italic-map.svg/131px-Italic-map.svg.png)

![Museum courtyard.[notes 68]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/37/Come_-_Archeological_museum_1.JPG/270px-Come_-_Archeological_museum_1.JPG)