Euwallacea interjectus

| Euwallacea interjectus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Suborder: | Polyphaga |

| Infraorder: | Cucujiformia |

| Family: | Curculionidae |

| Genus: | Euwallacea |

| Species: | E. interjectus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Euwallacea interjectus (Blandford, 1894)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Euwallacea interjectus is a species of ambrosia beetle in the species complex called Euwallacea fornicatus. It is native to Asia but has been introduced to the Western hemisphere over the last century.[1][2]

Taxonomy

[edit]

The E. interjectus is part of the Asian ambrosia beetle species complex. These insects have a symbiosis with ambrosia fungi.[1]

Euwallacea validus

[edit]A sister species in the same genus, Euwallacea validus, looks almost identical to E. interjectus.[1] They differ in their fungal associations, host trees, and potential for detrimental effects on the economy.[1] E. validus and E. interjectus's similar appearance can lead to confusion between the two species.[1] DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) sequencing has aided in identification.[1]

To differentiate between the two species morphologically, the shape of the declivity, punctures, and placement of the tubercles on the base of the body can help identify between the two species.[1] In E. interjectus, the declivity (downward slope) is gradually sloped from the base apex, thus giving a smoother appearance.[1]

Morphology

[edit]Adult body sizes range from 3.5 to 9 millimetres (0.14 to 0.35 in) in length, with a mean length of 3.78 millimetres (0.149 in), and range in width from 2.4 to 2.64 millimetres (0.094 to 0.104 in).[3] The species is known for its pronotum, a plate-like structure that covers the thorax, and spindles that are present all over the body.[1] These beetles range in color from brown to black.[3] The male body is significantly smaller than the female and thus requires less food.[4] Moreover, females are the ones that have mycangia, a structure that allows for the store of fungi, and males are rarely ones that can infect fungi.[5]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]E. interjectus is native to Asia. However, due to increasing trade and globalization, new populations have been found widely in warm regions of the globe.[1] E. interjectus is found in Myanmar, Japan, North Korea, South Korea, China, Taiwan, Tibet, India, Indonesia (Borneo, Java, Mentawei, Sumatra), Malaysia, Sarawak, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, and recently the United States of America and Argentina.[6][7][3][8]

United States

[edit]E. interjectus was first collected in the United States on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, in 1976.[1] The first reported mainland collection was in 2011 in Alachua County, Florida.[1] While it does not appear to be a primary pest on plants, it has been known to be abundant in the U.S., and mass outbreaks on water-stressed boxelder maples have been observed.[9][1]

As of 2015, E. interjectus occupies the lower southwest of the United States.[1] Genetic studies provide insight to the spread of E. interjectus to the United States, where three separate introductions took place: Hawaii (1976), Louisiana (1984), and Texas (2011).[1] E. interjectus is mostly commonly seen in Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, and South Carolina.[1] E. validus is most present in the northeast United States, however, overlap has been seen around the border of North and South Carolina and around Georgia.[1] Given their similar appearances, confirmation of species distribution is needed.[1]

Argentina

[edit]The E. interjectus came to Argentina via trade and were first found in April 2009 on a Populus deltoides plantation. The species has had a detrimental effect on poplars (Populus spp: Salicaceae),[8] which are used for lumber and reconstituted board products.[8] The non-native species has become incredibly invasive in plantations in Argentina.[8] While E. interjectus typically colonizes dead trees, it has been known to attack live trees also.[8]

Japan

[edit]E. interjectus has affected Japanese fig orchards, contributing to fig wilt.[10] E. interjectus acts as a vector of Ceratocystis ficicola, a pathogenic fungus that causes wilt disease in fig trees (Ficus carica L.).[10]

China

[edit]Shanghai

[edit]Despite the eastern China origin of E. interjectus, in April 2014 E. interjectus was found in Pudong New Area in Shanghai, China.[9] These beetles occupied poplar trees (Populus x canadensis), where it was observed that there were "noodle-like frass extrusions and gallery entrances" on poplar trees in the region.[9]

Life cycle

[edit]Not much is known about the life cycle of E. interjectus in the wild. However, studies under experimental conditions have provided insights on the life cycle and breeding times.[11] E. interjectus starts as an egg, and then progresses to a larva, then to a pupa, then lives as an adult.[11] The species lives inside plants for all of its life, except during dispersal. E. interjectus breeds throughout the year.[12][13][14]

E. interjectus act as a fungal vector, transporting fungi to and from their natal galleries in the mycangia.[11] After the fungus is released from the mycangia, the fungi grow in galleries, providing nutrition.[11] The sex ratio of adults from the galleries was about 31:1 female to male,[15] compared to that of the Xyleborini ambrosia beetle, which has an average sex ratio of 13:1.[15]

Mating

[edit]E. interjectus, like other ambrosia beetles, are sexually dimorphic, where the role of a male is limited to mating.[4] E. interjectus follows haplodiploid mating—females have two sets of chromosomes but males only one—and inbreeding. Thus, only one female beetle is needed to establish a new population in a new environment,[14] posing a high risk of invasion. Haplodiploid mating has developed as a mechanism that filters out harmful inbreeding-related abnormalities.[16] If inbreeding-related abnormalities such as recessive lethal and deleterious alleles are expressed in haploid males, it leads to the death of these individuals.[14] They rarely appear in diploid females, and thus prevent these deleterious conditions from entering the population.[14]

Diet

[edit]Euwallacea interjectus exhibits a mutual symbiotic relationship with ambrosia fungi as a nutritional source.[17] Like other ambrosia beetles, the beetles will create tunnels in dead or stressed trees to cultivate fungal gardens as a food source. E. interjectus is unique in that it will, at times, choose healthy and alive trees as hosts.[17]

E. interjectus mainly invades the phloem and xylem of host plants, with known hosts being poplar and rubber trees.[14] E. interjectus often chooses trees that are weak from droughts or depleted of resources, thus those less resistant to attacks from beetles.[14] In addition, they prefer softer wood trees as hosts.[14] The spread and invasion of E. interjectus has been more apparent in high-density planting sites.[9] Because of more resource competition, high-density planting sites are more prone to weakened host resistance.[9]

Relationship to the environment

[edit]

These non-native beetles have entered these various habitats because of human trade as the movement of timber and other tree-based products has acted as vessels for transport.[8] E. interjectus' presence in Argentina serves as an example for the concern of the species' invasiveness.[8] E. interjectus is part of a few species that attack living trees and prefers high-density plantations, thus the species has impacted several plantations globablly.[8] In 1992, it was determined that E. interjectus did not affect poplar trees outside its natural range of distribution, however, these beetles are now abundant in the Delta of Parana River region, and several incidences of mass attack on live water-stressed poplars have been observed.[8]

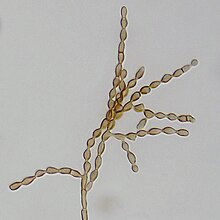

Relationship with fungi

[edit]The mutual symbiotic relationship between E. interjectus and fungi is complex. The fungi are pathogenic to the host tree, which can lead to tree dieback and mortality.[17] This is a result of inoculation with existing fungi or by mass inoculation of fungal pathogens by the pests.[17] Ambrosia beetle-associated fungi compete with pre-existing decaying fungi of the woody tissues and reduce the rate of decay.[18] However, in native areas, it has been seen to have a more promiscuous relationship.[17] Compared to a strictly obligate combination, which is seen in invaded areas.[17] It has also been seen that the proportion of fungal species that an individual holding and consumption volume shifts over the developmental and maturation period.[17]

All over the world, E. interjectus act as vectors for different fungi. In Japan, it was identified that 13 filamentous fungi use E. interjectus as a vector: Fusarium kuroshium, Arthrinium arundinis, Cladosporium cladosporioides, Acremonium sp., Fusarium decemcellulare, Xylariales sp., Pithomyces chartarum, Roussoella sp., Phialophora sp., Stachybotrys longispora, Paecilomyces formosus, Sarocladium implicatum, and Bionectria pityrodes.[15]

Control methods

[edit]In order to control E. interjectus infestation, chemical insecticides can be applied to the bark and trunk of trees, or the whole tree, to control the number of adult beetles that emerge from the tunnel.[12][13] However, because the timing of breeding is difficult to predict, given that E. interjectus "breeds throughout the year in many regions", it makes it difficult to know exactly when to apply the insecticide.[12][13] However, whole body desiccating of E. interjectus has been incredibly effective against larvae, adults, and symbiotic fungi.[9]

Relationship to humans

[edit]Due to the invasive nature of E. interjectus and the damage imposed on trees, they have become a problem for the lumber, pulp, and paper industry.[8] Their effects on the economy have drawn research attention, to develop insecticides and remedies to prevent damage to plantations around the world.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Cognato, Anthony I.; Hoebeke, E. Richard; Kajimura, Hisashi; Smith, Sarah M. (1 June 2015). "History of the Exotic Ambrosia Beetles Euwallacea interjectus and Euwallacea validus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Xyleborini) in the United States". Journal of Economic Entomology. 108 (3): 1129–1135. doi:10.1093/jee/tov073. PMID 26470238.

- ^ "Species Euwallacea interjectus". bugguide.net. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ a b c "Euwallacea interjectus". Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ a b Knížek, M.; Beaver, R. (2004), Lieutier, François; Day, Keith R.; Battisti, Andrea; Grégoire, Jean-Claude (eds.), "Taxonomy and Systematics of Bark and Ambrosia Beetles", Bark and Wood Boring Insects in Living Trees in Europe, a Synthesis, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 41–54, doi:10.1007/1-4020-2241-7_5, ISBN 978-1-4020-2240-1, retrieved 1 March 2024

- ^ Kasson, Matthew T.; O’Donnell, Kerry; Rooney, Alejandro P.; Sink, Stacy; Ploetz, Randy C.; Ploetz, Jill N.; Konkol, Joshua L.; Carrillo, Daniel; Freeman, Stanley; Mendel, Zvi; Smith, Jason A.; Black, Adam W.; Hulcr, Jiri; Bateman, Craig; Stefkova, Kristyna (1 July 2013). "An inordinate fondness for Fusarium: Phylogenetic diversity of fusaria cultivated by ambrosia beetles in the genus Euwallacea on avocado and other plant hosts". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 56: 147–157. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2013.04.004. ISSN 1087-1845. PMID 23608321.

- ^ Yin, H.-F.; H. Fu-Sheng; L. Zhao-Lin (1984). "Coleoptera: Scolytidae". Science Press, Beijing (in Chinese). Economic Insect Fauna of China (Fasc. 29): 205.

- ^ "Bark and Ambrosia Beetles of , Euwallacea interjectus (Blandford 1894) (introduced)". www.barkbeetles.info. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Landi, Lucas; Braccini, Celina Laura; Knížek, Milos; Pereyra, Vanina Antonella; Marvaldi, Adriana Elena (April 2019). "A Newly Detected Exotic Ambrosia Beetle in Argentina: Euwallacea interjectus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae)". Florida Entomologist. 102: 240–242. doi:10.1653/024.102.0141. hdl:20.500.12123/5529. S2CID 196683566.

- ^ a b c d e f Wang, Zhangxun; Li, You; Ernstsons, A. Simon; Sun, Ronghua; Hulcr, Jiri; Gao, Lei (2021). "The infestation and habitat of the ambrosia beetle Euwallacea interjectus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in the riparian zone of Shanghai, China". Agricultural and Forest Entomology. 23: 104–109. doi:10.1111/afe.12405. S2CID 225316402. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ a b Jiang, Zi-Ru; Kinoshita, Shun'ichi; Sasaki, Osamu; I. Cognato, Anthony; Kajimura, Hisashi (June 2019). "Non-destructive observation of the mycangia of Euwallacea interjectus (Blandford) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) using X-ray computed tomography". Entomological Science. 22 (2): 173–181. doi:10.1111/ens.12353. S2CID 91516805.

- ^ a b c d Jiang, Zi-Ru; Masuya, Hayato; Kajimura, Hisashi (July 2022). "Fungal flora in adult females of the rearing Pppulation of ambrosia Beetle Euwallacea interjectus (Blandford) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae): Does it differ from the wild population?". Diversity. 14 (7): 535. doi:10.3390/d14070535. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ a b c Mayorquin, Joey S.; Carrillo, Joseph D.; Twizeyimana, Mathias; Peacock, Beth B.; Sugino, Kameron Y.; Na, Francis; Wang, Danny H.; Kabashima, John N.; Eskalen, Akif (July 2018). "Chemical Management of Invasive Shot Hole Borer and Fusarium Dieback in California Sycamore (Platanus racemosa) in Southern California". Plant Disease. 102 (7): 1307–1315. doi:10.1094/PDIS-10-17-1569-RE. ISSN 0191-2917. PMID 30673581.

- ^ a b c Eatough Jones, Michele; Paine, Timothy D. (August 2015). "Effect of chipping and solarization on emergence and boring activity of a recently introduced ambrosia beetle (Euwallacea sp., Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in Southern California". Journal of Economic Entomology. 108 (4): 1852–1859. doi:10.1093/jee/tov169. ISSN 0022-0493. PMID 26470327.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hu, Jiafeng; Zhao, Chen; Tan, Jiajin; Lai, Shengchang; Zhou, Yang; Dai, Lulu (1 September 2023). "Transcriptome analysis of Euwallacea interjectus reveals differentially expressed unigenes related to developmental stages and egg laying". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics. 47: 101100. doi:10.1016/j.cbd.2023.101100. ISSN 1744-117X. PMID 37329642. S2CID 258996027.

- ^ a b c Jiang, Zi-Ru; Masuya, Hayato; Kajimura, Hisashi (28 September 2021). "Novel Symbiotic Association Between Euwallacea Ambrosia Beetle and Fusarium Fungus on Fig Trees in Japan". Frontiers in Microbiology. 12. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.725210. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 8506114. PMID 34650529.

- ^ Berger, Matthew C. (1 January 2017). "Interactions between Euwallacea Ambrosia Beetles, Their Fungal Symbionts and the Native Trees They Attack in the Eastern United States". Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. doi:10.33915/etd.5186.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carrillo, Joseph D.; Rugman-Jones, Paul F.; Husein, Deena; Stajich, Jason E.; Kasson, Matt T.; Carrillo, Daniel; Stouthamer, Richard; Eskalen, Akif (December 2019). "Members of the Euwallacea fornicatus species complex exhibit promiscuous mutualism with ambrosia fungi in Taiwan". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 133: 103269. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103269. PMID 31518652.

- ^ Gugliuzzo, Antonio; Biedermann, Peter H. W.; Carrillo, Daniel; Castrillo, Louela A.; Egonyu, James P.; Gallego, Diego; Haddi, Khalid; Hulcr, Jiri; Jactel, Hervé; Kajimura, Hisashi; Kamata, Naoto; Meurisse, Nicolas; Li, You; Oliver, Jason B.; Ranger, Christopher M. (June 2021). "Recent advances toward the sustainable management of invasive Xylosandrus ambrosia beetles". Journal of Pest Science. 94 (3): 615–637. doi:10.1007/s10340-021-01382-3. hdl:10045/115553. ISSN 1612-4758.