Fisher Fine Arts Library

| Anne and Jerome Fisher Fine Arts Library | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former names | Furness Library, Furness Building | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Library | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architectural style | Venetian Gothic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | University City | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Address | 220 South 34th Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Named for | Anne and Jerome Fisher | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1890 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Renovated | 1986-1991 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | University of Pennsylvania | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Material | Sandstone, brick, terracotta | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Size | 65,026 square feet (6,041.1 m2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Floor count | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Design and construction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architect(s) | Frank Furness | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architecture firm | Furness, Evans & Company | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Renovating team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Renovating firm | Venturi, Raunch, Scott, Brown and Associates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

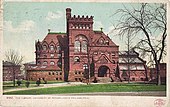

The Fisher Fine Arts Library was the primary library of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia from 1891 to 1962. The red sandstone, brick-and-terra-cotta Venetian Gothic giant, part fortress and part cathedral, was designed by Philadelphia architect Frank Furness (1839–1912).

History

[edit]The cornerstone was laid in October 1888, construction was completed in late 1890, and the building was dedicated in February 1891.[4]

Following completion of the Van Pelt Library in 1962, it was renamed the Furness Building (after its architect), and housed the university's art and architecture collections. The building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1985.[5]

The Furness Building was renamed the Anne and Jerome Fisher Fine Arts Library following a six-year, $16.5-million restoration, completed in 1991.[6] It is located on the east side of College Green, at Locust Walk and 34th Street.

Design

[edit]The library's plan is exceptionally innovative: circulation to the building's five stories is through the tower's staircase, separated from the reading rooms and stacks.

The Main Reading Room is a soaring four-story brick-and-terra-cotta-enclosed space, divided by an arcade from the two-story Rotunda Reading Room. The latter has a basilica plan – with seminar rooms grouped around an apse (like side-chapels) – the entire space lighted by clerestory windows. Above the Rotunda Reading Room is a two-story lecture hall, now an architecture studio. The Main Reading Room, with its enormous skylight and wall of south-facing windows, acts as a lightwell, illuminating the surrounding inner rooms through leaded glass windows.

The three-story fireproof stacks are housed in a modular iron wing, with a glass roof and glass-block floors to help light the lower levels. It was designed to initially hold 100,000 books – but also to be continuously expandable, one bay at a time, with a movable south wall. Furness's perspective drawing highlighted this growth potential by showing nine-bay stacks,[7] although the initial three-bay stacks were never expanded.

Throughout the building are windows inscribed with quotations from Shakespeare, chosen by Horace Howard Furness (Frank's older brother), a University lecturer and a preeminent American Shakespearean scholar of the 19th century. The architect collaborated with Melvil Dewey, creator of the Dewey Decimal System, and others to make this the most modern American library building of its time.[8]

"The plans I sketched with Mr. Furness late that evening, seem to me better than any college library has yet adopted." — Melvil Dewey.[9]

The Henry Charles Lea Library, a two-story addition to the building's east side, was designed by Furness, Evans & Company and completed in 1905.[6]

Rejection

[edit]Within a generation, Frank Furness's exuberant masterwork was considered an embarrassment. The University Museum moved to its own building in 1899. In 1915, the Duhring Wing was built at the south end of the stacks, making their designed expansion impossible.[10] Architect Robert Rodes McGoodwin drew up plans to cloak the entire building in sedate Collegiate Gothic brick and stone.[11] The first step toward this was the 1931 addition of a reading room facing College Green (now the Arthur Ross Gallery) that masked the iron-and-glass stacks.[12] Almost perversely, McGoodwin's incongruous Collegiate Gothic addition was dedicated as a memorial to Horace Howard Furness; H. H. Furness's Shakespeare home library was housed in the addition before being moved to Van Pelt Library. A garden with plants found in Shakespeare's works was grown in front of the addition.[13]

The building served as the main library of the University of Pennsylvania until the construction of Van Pelt Library in 1962. Today it houses collections related to architecture, landscape architecture, city and regional planning, historic preservation, history of art, and studio arts.

Belated appreciation

[edit]In 1957, Penn-trained architect and Philadelphia Bulletin cartoonist Alfred Bendiner invited Frank Lloyd Wright to tour the Victorian behemoth, then threatened with demolition. Wright proclaimed, "It is the work of an artist."[14]

The Furness Library was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972;[2] was additionally listed as a contributing property in the University of Pennsylvania Campus Historic District in 1978; and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1985.[1][3]

Between 1986 and 1991, the building was restored by a team that included Venturi, Rauch, Scott Brown & Associates, Inc., CLIO Group, Inc., and Marianna Thomas Architects.[15][16] On the occasion of its centennial in February 1991, it was rededicated as the "Anne & Jerome Fisher Fine Arts Library" (named for the restoration's primary benefactors). The $16.5-million restoration garnered rave reviews from New York Times architectural critic Paul Goldberger,[17] and received national awards from the Victorian Society in America (1991), the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (1992), and the American Institute of Architects (1993).[13]

The restored building was featured prominently in the 1993 film Philadelphia.

In a 2009 appreciation in The Wall Street Journal, architectural historian Michael J. Lewis called it "a cheeky act of architectural impertinence" and "the last of its kind": "Today, the University of Pennsylvania building, now known as the Fisher Fine Arts Library, is widely acknowledged as one of the great creations of 19th-century American culture, and the principal work of its architect, Frank Furness (1839-1912)."[18]

Arthur Ross Gallery

[edit]Horace Howard Furness's collection of Shakespeare was moved to Van Pelt Library in the 1960s. The former Furness Reading Room was converted into the Arthur Ross Gallery, which houses the university's art collection. Opened in 1983,[19] the gallery is named for its benefactor, noted philanthropist Arthur Ross, who started his college studies at the University of Pennsylvania, but later transferred to Columbia University.[20] Admission to the public is free.

Gallery

[edit]-

Arthur Ross Gallery (1931), right, and Duhring Wing (1915), far right.

-

Gargoyles.

-

Lantern of the porch and the leaded glass fanlight.

-

Henry Charles Lea Library bay window

See also

[edit]- List of National Historic Landmarks in Philadelphia

- National Register of Historic Places listings in West Philadelphia

References

[edit]- ^ a b Carolyn Pitts (August 10, 1984). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Furness Library, School of the Fine Arts, University of Pennsylvania" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying four photos from 1964 (32 KB)

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ a b "Furness Library, School of Fine Arts, University of Pennsylvania". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ^ Applications for Historical Landmark Status Archived July 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Accessed July 20, 2007

- ^ "Asset Detail". focus.nps.gov. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Anne and Jerome Fisher Fine Arts Library - Chronology from Philadelphia Architects and Buildings.

- ^ Elevation and perspective drawing Archived 2008-06-10 at the Wayback Machine from Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania

- ^ Edward R. Bosley, University of Pennsylvania Library (London: Phaidon Press, 1996), pp. 17-22.

- ^ Melvil Dewey to Provost William Pepper, 20 April 1887, University of Pennsylvania Archives.

- ^ Duhring Wing, from University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ Proposed alterations to University of Pennsylvania Library (1931) from University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives.

- ^ Arthur Ross Gallery from University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ a b Bosley, p. 60.

- ^ Alfred Bendiner, Bendiner's Philadelphia (New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1964), pp. 40-41. Bendiner cartoon from Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania

- ^ Restoration drawings Archived 2009-01-07 at the Wayback Machine from Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania

- ^ "Restoration of the Furness Building/Fisher Fine Arts Library, University of Pennsylvania" (PDF). Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ Paul Goldberger, "In Philadelphia, a Victorian Extravaganza Lives," The New York Times, June 2, 1991.

- ^ Lewis, Michael J. (November 14, 2009). "This Library Speaks Volumes". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ "History". Arthur Ross Gallery. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (September 11, 2007). "Arthur Ross, Investor and Philanthropist Who Left Mark on the Park, Dies at 96". New York Times. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

External links

[edit]- Official Site

- Arthur Ross Gallery

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA-1644, "University of Pennsylvania, Furness Building", 10 photos, 1 photo caption page

- Furness Fine Arts Building in Winter

- Library buildings completed in 1891

- Libraries on the National Register of Historic Places in Philadelphia

- University of Pennsylvania campus

- University and college academic libraries in the United States

- National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania

- Frank Furness buildings

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Philadelphia

- 1891 establishments in Pennsylvania

- University and college buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania

- Individually listed contributing properties to historic districts on the National Register in Pennsylvania