Gia-Fu Feng

Gia-fu Feng | |

|---|---|

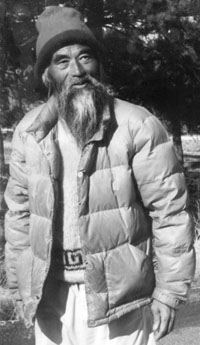

Gia-fu Feng, c. 1984 | |

| Native name | Chinese: 馮家福 |

| Born | January 10, 1919 Yuyao, Zhejiang Province, China |

| Died | June 12, 1985 (aged 66) Wetmore, Colorado, United States |

| Alma mater | Southwest Associated University, China The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania |

| Spouse |

|

| Gia-Fu Feng | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 馮家福 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 冯家福 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Gia-fu Feng (Chinese: 馮家福; January 10, 1919 – June 12, 1985) was a prominent translator of classical Chinese Taoist philosophical texts, founder of an intentional community called Stillpoint, and leader of classes, workshops, and retreats in the United States and abroad based on his own unique synthesis of tai chi, Taoism, and other Asian contemplative and healing practices with the Human Potential Movement, Gestalt therapy, and encounter groups.

He was associated with Alan Watts, Claude Dalenberg, and the American Academy of Asian Studies; Jack Kerouac, Joanne Kyger, Gary Snyder, and the Beat Generation; and Abraham Maslow, Fritz Perls, Dick Price, Michael Murphy, and the Esalen Institute.

He is best known for his bestselling translations and calligraphy of the Tao Te Ching and the Zhuangzi Inner Chapters accompanied by black-and-white photographs by Jane English in the books Lao Tsu / Tao Te Ching, first published in 1972, and Chuang Tsu / Inner Chapters, first published in 1974.

Early life

[edit]Gia-fu Feng, later known as "Jeff" to some of his American friends and family but "Gia-fu" to most, was born in China in 1919, the third of nine children in a wealthy and influential family. His father was a banker who rose to prominence with the Ta-Ching Government Bank, then co-founded and served as president of the Bank of China in Shanghai. His mother died when he was 16. He was educated at private boarding schools, and received tutoring at home in Chinese classics and English. One of his English tutors was the sister of the British commissioner of Shanghai Customs.[1]

His family practiced traditional Chinese religion, observing all twenty-four annual festivals, for example traveling from Shanghai to visit their ancestors' tombs in Yuyao, Zhejiang Province, during the Qingming Festival. When he was twelve years-old his older siblings converted to Christianity, and at their recommendation during his first time living away from home as a young adult he was baptized and participated in a fervently puritanical church group, but he drifted away after a year.[1]

University, banking, and Wall Street

[edit]China

[edit]Feng first left home in 1938 during the Japanese invasion, to complete a bachelor's degree in the liberal arts at Southwest Associated University in unoccupied western China, where he lived through Japanese bombing and persevered, enthusiastically studying under some of China's top scholars.[1]

After graduation, despite his preference for poetry, literature, and philosophy, his father's connections led him to work in local banking in and around Kunming. He showed great aptitude and made a quite a lot of money from involvement in some of the murkier transactions, as was common in wartime China. He lived in and managed a villa that hosted many prominent Chinese and foreign visitors, where he met Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, General Claire Chennault, US Vice President Henry A. Wallace, and Lady Mountbatten, among others, and successfully navigated a difficult political environment. He was also in charge of arranging dance parties at the villa for American soldiers.[1]

He once commented that he had become a millionaire three times in his life, giving his money away each time. The first time was when he worked as a banker in the Kunming area, as he freely lent his money to friends and generally treated himself and everyone he knew to a good time. Yet in his memoirs he noted that he was also profoundly affected by the extremes of wealth and poverty he encountered then, especially the grinding misery of laborers forced to work on construction of the Burma Road, and the horrors of war he witnessed in Kunming and Shanghai.[1]

United States

[edit]After the war he returned home to Shanghai in 1946, but left again in 1947 to go to the U.S. for a master's degree in international finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. While at Penn he frequently visited the Pendle Hill Quaker Center for Study and Contemplation. He found himself accepted and drawn to that community, and became interested in many aspects of Quaker thought.[1]

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, his father recommended that he remain abroad due to the uncertain political and economic situation, and then in 1950 when the Korean War broke out the United States prohibited Chinese students from returning to China. He enrolled in a Ph.D. program in statistics at New York University, worked for a Wall Street financial firm, lived in an international student hostel and then a Quaker-run cooperative house in New York, and continued to visit Pendle Hill on weekends.[1]

But with his prospects for advancement limited by his visa status, and feeling alienated and unhappy in New York, he set out across the country driving his "jalopy", seeking a new way of life and a new understanding of his place in America.[1]

Seeking the Way

[edit]Journey to the South, and West

[edit]His first destinations show his growing interest in intentional communities. He visited the Macedonia Cooperative Community of pacifists in Habersham County, Georgia, followed by a long stay doing farm work at Koinonia Farm, an interracial Christian community in Sumter County, Georgia focused on civil rights. There he experienced firsthand the surrounding white community's hostility towards Black people and Koinonia in reaction to the 1951 filing of Brown v. Board of Education.[1]

He then travelled to Orcas Island near Seattle for seminars on civil rights and international harmony sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization, and briefly lived at a commune in Tuolumne County, California, before traveling on to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he soon found his way to the heart of the San Francisco Renaissance.[1]

American Academy of Asian Studies

[edit]In 1954 he stayed in Berkeley with a Quaker friend from Pendle Hill, Margaret Olney, and then began living, working, and attending classes at the American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco, after hearing a lecture by Alan Watts that he found life-changing.[1]

For the first time he encountered a Westerner presenting Taoism, Zen, and other ancient Eastern thought as an approach to modern everyday problems, and he declared the study of comparative religion his calling. Watts in turn found Feng fascinating, very much appreciated his classical Chinese education, and quickly put him to work translating Chinese religious and philosophical texts. Having found a home and a purpose, Feng decided to take advantage of a one-year window offered by the Refugee Relief Act and immigrate to the United States.[1]

Over the next two years at the Academy he befriended fellow student Dick Price, future cofounder of Esalen Institute, and introduced Price to his first wife, Bonnie. He also shared much wine and many long philosophical conversations there with another fellow seeker, Jack Kerouac, who introduced him to many leading lights of the Beat Generation. And he enrolled in classes at the Academy offered by Watts, Gi-ming Shien, Frederic Spiegelberg, Haridas Chaudhuri, C. P. Ramaswamy Iyer, Judith Tyberg, Rom Landau, Saburo Hasegawa, and G. P. Malalasekhara.[2][3][1]

East-West House

[edit]In 1956 Feng co-founded East-West House, an intentional community in San Francisco, with a group from the Academy led by Ananda Claude Dalenberg, all moving on because Alan Watts was leaving the school. No longer doing translation for Watts, Feng studied banking at San Francisco State University and supported himself with a variety of odd jobs, including accounting, substitute teaching, and dog walking.[1]

East-West House attracted members from many walks of life, including poets and writers like Feng's good friends Joanne Kyger and Gary Snyder, Asian Studies scholars like his teacher from the Academy, Gi-ming Shien, and artists like house leader Knute Stiles. Kerouac was a guest, and based several characters in his novels on House residents. Feng, in addition to his pursuit of philosophical and spiritual truths, was known there for his special Chinese pork recipe. Dalenberg later recalled that during this time Feng maintained his involvement with the local Quaker community and further developed his interest in "old Chinese religion".[4][1]

Feng's news of East-West House drew Dick Price back to San Francisco after some time living back east, and his experience there was one influence on Price's interest in establishing a new community and learning space with Michael Murphy at a place called Slate's Hot Springs, which they first renamed Big Sur Hot Springs, and then Esalen Institute.[2][3]

The Way of Esalen

[edit]"I remember", someone once said about his early visits to Esalen, "that there was either a guy there named Gia Fu who taught Tai Chi, or a guy named Tai Chi who taught Gia Fu."[2]

In 1962 Feng became one of the first staff members at Esalen Institute, as "the accountant (he brought his own abacus), keeper of the baths, and resident Chinese mystic".[2] He led morning tai chi classes there, and those became the foundation for the bodywork portion of Esalen's three-part curriculum as it matured, the other two being Gestalt therapy and encounter groups. He later trained in shiatsu in Japan and begin offering that at Esalen as well.[2][3][1]

With Esalen as his base, he was becoming more widely known in the region and nationwide for his tai chi classes focused on the transformation of body and spirit. A 1962 advertisement in New York's Village Voice for Emerson College of Pacific Grove was headlined with his name: "Gia Fu Feng is there, teaching culture east and west on the beach in Monterey".[5]

But Esalen was also to be transformative for him. That same year he was staffing the front desk when he recognized a guest's name and enthusiastically welcomed Abraham Maslow, who had wandered in looking for a motel room. Maslow's book Towards a Psychology of Being was already a major influence at Esalen, closely read by Feng and others there, and Maslow became a regular visitor and influence himself. Humanistic psychology and the Human Potential Movement were to become central to Feng's path forward.[2][3][1]

A new Gia-fu

[edit]In 1963 at the first Gestalt therapy workshop there, Feng volunteered to be the first to take the "hot seat" in front of the group. He developed great respect for Gestalt therapy creator Fritz Perls, who became a fixture at Esalen beginning in 1964, and maintained that respect as well as a sympathetic tolerance regardless of how the always irascible Perls treated him and others. Feng was also there for the earliest encounter groups at Esalen, on leadership training in group dynamics. While doing his own work he studied and absorbed many new ideas, especially from Perls.[2][3][1]

He now believed that psychotherapy was key to helping Westerners understand Eastern thought. He was particularly struck by Fritz Perls' statement at the start of every Gestalt therapy group that the goal of his fierce leadership was a "sudden awakening" for participants. Feng said that was in essence a Zen-like "satori" realization, and Feng developed his own techniques based on Gestalt therapy and encounter to help people get past their "hang-ups" and get on with natural living like the Taoist sages of old. Dick Price developed a similar synthesis with Eastern thought that he called Gestalt practice. But Price softened the "hot seat" experience, while Feng embraced the fierceness. In fact, Claude Dalenberg later said that he no longer recognized Feng's personality when he visited him at Esalen. As Feng's biographer states, gone was the well-bred polite persona of the 1950s, and in its place a new Gia-fu, a self-described "Taoist rogue", and a strong patriarchal figure who could lead a community, but the seeds of this fully realized Gia-fu were always there.[6][3][1]

In 1966 he founded Stillpoint, an intentional community in Los Gatos, California, but continued teaching tai chi at Esalen for the next few years, driving the two-hundred-mile round trip to Big Sur once a week,[1] and he remained publicly associated with Esalen. In 1969 an ad for Human Potential Movement workshops at Aureon Institute in New York listed him as part of a group of visiting Esalen instructors.[7] One of his students at Esalen was Anne Heider. With her husband John Heider, who led encounter groups under Will Schutz, she trained in Esalen massage and discovered Feng's tai chi classes. She learned some postures well enough to lead a class when Feng was absent, and joined in his next project.[3][1]

First publication: Tai Chi and I Ching

[edit]His first book, Tai Chi, a Way of Centering, & I Ching, a Book of Oracle Imagery, was published in 1970.[8] He was encouraged by books published over the previous two years by other Esalen figures: Fritz Perl's In and Out of the Garbage Pail,[9] and massage guru Bernard Gunther's Sense Relaxation: Below Your Mind. Gunther's and Feng's books even shared the same publisher and a similar design.[10][1][2]

Alan Watts wrote a short foreword introducing his "very old friend", with this quoted on the back cover: "Gia-fu Feng is not just writing about the old Chinese way of life: he represents it; he is it." Laura Huxley wrote a thoughtful forward on the meaning within tai chi.[8] (She would go on to write an introduction to Wen-shan Huang's Fundamentals of Tai Chi Chuan as well.[11]) Jerome Kirk, UC Irvine professor of sociology and anthropology, wrote the introduction — a deep dive into the historical and metaphysical context — and helped with the I Ching translation.[8]

I Ching

[edit]Despite the book's title, the I Ching chapter is first. Also known as the Book of Changes, the I Ching had become very popular in the West as a source of divination, like creating an astrology horoscope but based on the ever-changing flow of possibility. It was also read as a representation of ancient Chinese philosophy and of Carl Jung's concept of synchronicity. Feng translated the ancient text into the popular vernacular of the California counterculture of the 1960s: "The freeway to Heaven. Groovy"; "Humility is groovy"; "Brotherhood in the suburbs is no fault".[8][1]

Tai chi

[edit]The tai chi section includes photographs of Anne Heider performing tai chi, taken by photographer Hugh Wilkerson on the beaches and hillsides of Big Sur. The sequence was the 24-movement simplified form developed from the movements of Yang-style tai chi by a Chinese government-appointed committee in 1956, and in his introduction to this chapter Feng referenced a 1961 official Beijing publication.[8] Feng also knew the full "108 postures" of the Yang-style long form,[12] but he had found that the simplified form best met the needs of most of his students, who were usually at Esalen for only a short while.[1]

He taught Anne some of the postures just before each photograph was taken. Years later she commented that she could have performed much better after she trained with traditional tai chi master Wu Ta-yeh, a disciple of Tung Hu Ling and founder of the Taijiquan Tutelage of Palo Alto. She realized that in comparison Feng was an "instant master" without the same depth of training, but she remained appreciative of his playing the tai chi master role in a "very Puckish, buccaneer manner" as he used tai chi to express his background and his cross-cultural truths, and she believed he drew on traditional training from his past.[1]

Feng never claimed to be a "master" of anything or anyone. He hated that term, and strongly denied he was a tai chi master, a Taoist master, or any other kind of master, even as his Tai Chi Camps became popular in the United States and abroad over the next dozen years. Asked about this, one Stillpoint community member familiar with Feng's unique blend of tai chi and Taoism with Gestalt therapy, encounter and more said he was less "master" and "more the trickster...like a character from a Chuang Tsu story...the one who wipes you out."[1]

Stillpoint: California and Vermont

[edit]Los Gatos, California

[edit]Stillpoint, the intentional community he founded in 1966, was to some a "Taoist meditation center". To others it was a "commune", and a clothing-optional one at that. For all participants, it was a place for natural living, community, healing, and personal growth. Founded at a rented property on Bear Creek Road in Los Gatos, California, the community built a large Chinese gate at the entrance, and various other additions and structures around the existing main building, including saunas, a large hot tub, and a tree house, as well as an organic garden and a chicken coop. Members paid three dollars per day or traded work on building and improvements, and all shared in the daily chores.[13][1]

The name Stillpoint comes from "the point in meditation between the in-breath and the out-breath; the point that is still — and empty." For Feng, learned in ancient Chinese culture, the term also represented a famous line from the Taoist classic Zhuangzi (Chuang Tsu), which tells us Confucius said people cannot see their reflection in running water but only in still water, and only through stillness can a leader bring the people to the point of stillness.[note 1] Also other references to leadership and stillness, such as the first line of the classic Great Learning about the virtue of leading the people to rest (be still) in excellence.[note 2] But to the average Westerner he simply explained that Stillpoint was a place to find the peace and contentment that Chinese call "settled heart" (Chinese: 安心; pinyin: ànxīn). Members of the community were called "Stillpointers", even after they left.[1]

Days at Stillpoint always included tai chi. A typical routine also included predawn seated meditation, which struck one observer as a "quiet chaos" in which each participant was free to practice Zazen, chanting, or other techniques, yet also much like Quaker silent meeting. Each morning there was a community gathering, which another participant remembered as an "encounter group" session, in which members worked through interpersonal issues, chore selection, project planning, and more while Feng listened quietly. He would jump in with techniques based on Gestalt therapy and encounter group leadership, as well as Taoism and other Eastern thought, as needed to spur personal growth and group cooperation. Afternoons often included informal teaching and sharing on a wide range of topics, along with time for social activities, among as many as seventy residents and visitors at times. And much attention was given to preparation of meals for a healthy diet.[13][1]

It was here that Gia-fu Feng met Jane English, the physicist and photographer. She was invited to visit Stillpoint by a friend in 1970, and decided to stay. Within the year Feng and English were married in an informal outdoor ritual at Yosemite National Park, and again by Alan Watts in an impromptu ceremony during a gathering at Watts' home in Marin. And it was here that they began their collaboration on the first of two bestselling books. Other Stillpointers helped with that project too, in group sessions that were for them also seminars in ancient Chinese thought and culture.[1]

Calais, Vermont

[edit]After about five years in Los Gatos, tensions with neighbors led Feng to pull up roots in the spring of 1971 and lead a caravan of fifteen Stillpointers on a cross-country trip, with a long sojourn in Vermont where his friend Elizabeth Kent Gay offered the group rooms and camping space at her home and her daughter's home in Calais. Feng met Kent Gay in California while she was attending the Institute for Transpersonal Psychology in Menlo Park. She had since moved back to her home state and co-authored a series of Vermont cookbooks with her mother, Louise Andrews Kent.[1]

While in Vermont, Feng and English focused on completing their first joint book project, while continuing to lead the Stillpoint community there and on side-trips around the region. The two were also invited to visit Tibetan Buddhist leader Chögyam Trungpa, who had established one of his meditation centers in Vermont. As his biographer states, Feng did not want to be considered a "spiritual master" and was "most certainly not a Buddhist" despite his interest in Beat Zen, but he and Trungpa found much to share and discuss, and there would be further "occasional visits in the future".[1]

Then in October 1971 the group moved on to Colorado, with Feng and English making a fateful stop in New York City to meet with their publishers.[1]

Second publication: Lao Tsu / Tao Te Ching

[edit]

The success of Feng and English's Lao Tsu / Tao Te Ching[16] may owe much to an unexpected change of publisher. The book pairs Feng's translation of the ancient Tao Te Ching by Lao Tsu with black-and-white photographs by English, and with his calligraphy of the original Chinese text directly on the photos in the style of traditional Chinese paintings. They began the book in January 1971 in California and completed it that fall in Vermont, where English set up a darkroom in a Kent Gay family basement. They then brought a mock-up of the book, with the layout designed by English, to publishers in New York.[1]

Already a more polished effort than Feng's previous book, the project received an unexpected boost when their editor at Collier Books, which had first right of refusal, was unable to take it on and referred them to Toinette Lippe, an editor at Alfred A. Knopf, who met them without an appointment and saw the potential of their work. Lippe worked intently on polishing the translation in collaboration with Feng via mail, and published it under the Vintage Books imprint with much higher-quality production and marketing than Feng's relatively innocent first publication. The book's potential was further elevated by a ringing endorsement from Alan Watts on the back cover.[1][17]

Published in 1972, by the release of the 25th anniversary edition it had sold over one million copies and was the most popular translation of the Tao Te Ching.[17] Time magazine's 1972 review of the book was its first of any Tao Te Ching translation, despite the fact that only the Bible has been translated into English more times.[17] That same year the prominent Willard Gallery in New York exhibited photos and calligraphy from the book.[18][19] The book's success was life-changing for both authors. In addition to their new income, Feng gained worldwide renown that led new Stillpointers to him and led him to offer workshops and retreats around the world over the next ten years,[1] and in the following decades English published wall calendars, cards, and journals based on the book,[1][20] in addition to working with Lippe on updated and alternate editions with an introduction by Jacob Needleman.[21][22]

Stillpoint: Colorado and travel

[edit]The Stillpoint group spent the winter of 1971-72 in Mineral Hot Springs, Colorado, where Feng corresponded with Lippe on the final editing of the Tao Te Ching, and English shot a roll of film in the nearby Great Sand Dunes from which she later selected twelve photos for their next book, Chuang Tsu / Inner Chapters. They then moved on to Manitou Springs, renting until 1973 when Feng and English used their royalty advance as part of a downpayment on a house on Ruxton Avenue for the group. In 1977 Feng purchased property near Wetmore, Colorado and moved Stillpoint to that bucolic rural setting.[1]

Feng and English were invited to Thomas Jefferson College in Michigan for the spring 1973 semester, and Colorado College for two semesters in fall 1973 and spring 1974, where English taught courses on "Oriental Thought and Modern Physics" with Feng as guest lecturer, and where she and Feng taught tai chi. Feng also began leading "Tai Chi Camps" organized by his students, where he taught tai chi, qigong, acupressure, Chinese healing, Chinese calligraphy, and I Ching, and led group therapy sessions, first in the United States, and then starting in 1974 also overseas. The Tao Te Ching had been published in many languages around the world, which in turn led to invitations to lead camps in Europe, including England, Scotland, Germany, Holland, Switzerland, Denmark, France, and Spain, and in 1982 also Australia and New Zealand.[16][1]

In 1974 while in London on the way to join Feng at Tai Chi Camps in Europe, English encouraged their British publisher to take a chance on Fritjof Capra and his manuscript for The Tao of Physics, and on their return trip through London Feng and English met with Joseph Needham. Later that year Feng and English separated. In 1975 Feng made his only return trip to China, where he visited his family and discovered they had suffered greatly under Maoist campaigns, especially the Cultural Revolution. From 1975 to 1980 Micheline Wessler was Feng's partner, co-director of Stillpoint, and co-instructor at the Tai Chi Camps.[1]

By 1977 Stillpoint had grown to as many as fifty people, seventy-five percent from abroad (mostly Germany and Scandinavia), some there for short visits, some for many years. Stays were now seven dollars per day for the first week, and three dollars per day thereafter while sharing in the daily chores, with some making special arrangements in exchange for building and maintenance work. Throughout this period the group continued and deepened their tai chi, meditation, and other contemplative and healing practices, as well as their focus on health foods, natural living, and enjoyment of the outdoors. Drugs were not tolerated. Feng continued to facilitate cooperation and personal breakthroughs with his fierce techniques based on Gestalt therapy and encounter, blended with Taoism and other traditional Asian thought. Community members continued to be involved in Feng's translation work, which was for them somewhat like an ongoing seminar in ancient Chinese thought and culture.[1]

Third Publication: Chuang Tsu / Inner Chapters

[edit]The second book by Feng and English, Chuang Tsu / Inner Chapters, was first published in 1974 as a companion volume to their Lao Tsu / Tao Te Ching. Declaring that "Chuang Tsu was to Lao Tsu as Saint Paul was to Jesus and Plato to Socrates", the book contains the seven "Inner Chapters" that scholars agree were written by him. Other works traditionally attributed to Chuang Tsu were probably added by others.[23]

Also published by Knopf under the Vintage Books imprint, the design matched that of the Lao Tsu volume, with Feng's translation and calligraphy paired with English's black-and-white photographs and layout. A newspaper reviewer found the photographs "nothing short of superb - serene in composition and sensitively executed", and well-matched with the "fables, humor, poetry, and riddles" offering "kernels of everlasting truth".[24]

By the thirty-fifth anniversary edition the book had sold over 150,000 copies as Jane English guided it through several updated releases by various publishers,[1] with Chungliang Al Huang contributing an introduction to that anniversary edition and the narration for an audiobook version.[25][26] English also produced wall calendars with quotes and photographs from the Lao Tsu and Chuang Tsu books as well.[20]

Final years and death

[edit]In 1983 Feng married Sue Bailey in a ceremony at Stillpoint surrounded by the community and many columbine flowers, led by a friend certified as a minister of the Universal Life Church. He settled into a quieter life focused on a more serious, less "groovy" translation of the I Ching (Yijing), as well as a translation of the Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine (Huangdi Neijing), and writing his memoirs.[1]

He stopped traveling and reorganized his living arrangements at Stillpoint to accommodate growing weakness. He consulted with Western medical doctors, but for the most part focused on Eastern and natural health therapies. He named his friend Margaret Susan Wilson as his executor and willed his estate to her including his share of the Wetmore property. Susan, as she was known, was a civil rights attorney and a graduate of the California Institute of Integral Studies, the school formerly known as the American Academy of Asian Studies where Feng had studied with Alan Watts.[1]

On June 12, 1985, after leading a group session on translation of the I Ching, Gia-fu Feng quietly passed away while reclining in his wife's arms. The cause of death was most likely emphysema. He was buried four days later at Stillpoint in a funeral ceremony attended by three of his sisters along with friends, neighbors, and the Stillpoint community.[1]

Posthumous publication and legacy

[edit]In 1986 Sue Bailey published his final translation of the I Ching, as Yi Jing: Book of Changes.[27] Jane English continues to produce reprintings and new editions of the books she coauthored with Feng, as well as calendars, cards, and journals she designs based on those books. Their Tao Te Ching remains the bestselling English edition.[1]

Feng did not want the Stillpoint community to continue after his death, to prevent any veneration of him as founder of any kind of spiritual lineage. The community disbanded, and after a legal battle against local developers Susan Wilson became sole owner of the Wetmore property and prevented commercial development. After Susan's death from cancer in 1991, her sister Carol Ann Wilson developed partnerships with environmental education organizations for the site's use and maintenance, and in 2005 secured its preservation through a conservation land easement with the San Isobel Land Protection Trust, now part of Colorado Open Lands.[1]

In 1995 Carol Ann Wilson cofounded Stillpoint: A Center for the Humanities & Community, with a board of directors that included longtime Stillpointers. For almost twenty years the center produced a series of poetry readings, writer workshops, author talks, music programs and other events at Wetmore and in Boulder, Colorado. She also inherited responsibility for Feng's draft memoirs. After thirteen years of research and interviews in the United States and China she released a biography, Still Point of the Turning World: The Life of Gia-fu Feng, through Amber Lotus Publishing in 2009 and as a Kindle e-book in 2014.[1]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av Wilson, Carol Ann (2009). Still Point of the Turning World: The Life of Gia-fu Feng. Amber Lotus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60237-296-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anderson, Walter Truett (2004) [1983]. The Upstart Spring — Esalen and the Human Potential Movement: The First Twenty Years. Authors Guild Backprint. ISBN 0-595-30735-3. (Originally published by Addison-Wesley as The Upstart Spring: Esalen and the American Awakening)

- ^ a b c d e f g Kripal, Jeffrey John (2007). Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45371-2.

- ^ Morgan, Bill (2003). The Beat Generation in San Francisco: A Literary Tour. San Francisco: City Lights Publishers. p. IX, 151–152. ISBN 978-0872864177.

- ^ "Emerson College, in Pacific Grove, Calif". Village Voice. 1962-11-01. Retrieved 2024-01-24.

- ^ Gaines, Jack (1979). Fritz Perls here & now. Celestial Arts. p. 170. ISBN 0-89087-214-7.

- ^ "Aureon Institute". Village Voice. 1969-01-16. Retrieved 2024-01-24.

- ^ a b c d e Feng, Gia-fu (1970). Tai Chi, A Way of Centering & I Ching, a Book of Oracle Imagery. Collier Books. LCCN 70-97757.

- ^ Perls, Fritz (1969). In and Out of the Garbage Pail. Gestalt Journal Press. ISBN 978-0939266173.

- ^ Gunther, Bernard (1968). Sense Relaxation: Below Your Mind. Collier Books. ISBN 978-0356024387.

- ^ Huang, Wen-shan (1973). Fundamentals of Tai Chi Chuan. Hong Kong: South Sky Book Company. OCLC 11939381., revised editions OCLC 164796638, 966113835, 1002312809

- ^ Odsen, Dorothy A. (February 1982). "Taoism, T'ai Chi Ch'uan and the Aesthetics of Chinese Painting". Black Belt Magazine. ISSN 0277-3066.

- ^ a b "Stillpoint Taoist Meditation Center as a young adult in the early 1970s (Audio interview with Michael Hartman)". StoryCorp. December 1, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ Chuang Tsu (1974). "Chapter 5: Signs of Full Virtue". Chuang Tsu / Inner Chapters. Translated by Feng, Gia-fu; English, Jane. Vintage Books. p. 95. ISBN 0-394-71990-5.

- ^ Legge, James (2018). Confucian Analects, The Great Learning, The Doctrine of the Mean. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1387874279.

- ^ a b Feng, Gia-fu; English, Jane (1972). Lao Tsu / Tao Te Ching. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-71833-X.

- ^ a b c Lippe, Toinette (1997). "What Constitutes a Necessary Book?". Lao Tsu / Tao Te Ching, 25th Anniversary Edition. By Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0679776192.

- ^ "Continuing Group Shows - Photography". New York. December 11, 1973. ISSN 0028-7369. "Continuing Group Shows - Photography". New York. January 1, 1973. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ^ "At the Galleries - Photography". Village Voice. November 30, 1972. ISSN 0042-6180. "Galleries (advertisement)". New York Magazine. December 14, 1972. ISSN 0042-6180.

- ^ a b English, Jane (2023). Tao Calendar. Amber Lotus Publishing. ISBN 979-8898000257.

- ^ Needleman, Jacob (1989). Introduction. Tao Te Ching: Text Only Edition. By Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane; Lippe, Toinette. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0679724346.

- ^ Needleman, Jacob (2011). Introduction. Tao Te Ching with over 150 Photographs by Jane English. By Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane; Lippe, Toinette. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0307949301.

- ^ Feng, Gia-fu; English, Jane (March 12, 1974). Chuang Tsu / Inner Chapters. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-71990-5.

- ^ "Celestial Thoughts". Calgary Herald. Calgary. June 14, 1974. p. 90. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Huang, Chungliang Al (2008). Introduction. Chuang Tsu: Inner Chapters, a Companion to the Tao Te Ching. By Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane. Amber Lotus. ISBN 978-1602371170.

- ^ Huang, Chungliang Al (2014). "Narration". Chuang Tsu: Inner Chapters, a Companion to the Tao Te Ching — Audiobook. By Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane. Phoenix Books.

- ^ Feng, Gia-fu (1986). Yi Jing: Book of Changes. Mullumbimby, Australia: Feng Books. ISBN 978-0958812702.

Bibliography

[edit]Anderson, Walter Truett (2004) [1983]. The Upstart Spring — Esalen and the Human Potential Movement: The First Twenty Years. Authors Guild Backprint. ISBN 0-595-30735-3. (Originally published by Addison-Wesley as The Upstart Spring: Esalen and the American Awakening)

English, Jane (2023). Tao Calendar. Amber Lotus Publishing. ISBN 979-8898000257.

Feng, Gia-fu; English, Jane (1974). Chuang Tsu / Inner Chapters. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-71990-5.

Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane; Huang, Chungliang Al (2008). Chuang Tsu: Inner Chapters, a Companion to the Tao Te Ching. Amber Lotus. ISBN 978-1602371170.

Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane; Huang, Chungliang Al (2014). Chuang Tsu: Inner Chapters, a Companion to the Tao Te Ching — Audiobook. Phoenix Books.

Feng, Gia-fu; English, Jane (1972). Lao Tsu / Tao Te Ching. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-71833-X.

Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane; Huang, Chungliang Al; Lippe, Toinette (1997). Lao Tsu / Tao Te Ching, 25th Anniversary Edition. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0679776192.

Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane; Lippe, Toinette; Needleman, Jacob (1989). Tao Te Ching: Text Only Edition. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0679724346.

Feng, Gia-Fu; English, Jane; Lippe, Toinette; Needleman, Jacob (2011). "Introduction". Tao Te Ching with over 150 Photographs by Jane English. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0307949301.

Feng, Gia-fu (1970). Tai Chi, A Way of Centering & I Ching, a Book of Oracle Imagery. Collier Books. LCCN 70-97757.

Feng, Gia-fu (1986). Yi Jing: Book of Changes. Mullumbimby, Australia: Feng Books. ISBN 978-0958812702.

Gaines, Jack (1979). Fritz Perls here & now. Celestial Arts. p. 170. ISBN 0-89087-214-7.

Gunther, Bernard (1968). Sense Relaxation: Below Your Mind. Collier Books. ISBN 978-0356024387.

Kripal, Jeffrey John (2007). Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45371-2.

Morgan, Bill (2003). The Beat Generation in San Francisco: A Literary Tour. San Francisco: City Lights Publishers. ISBN 978-0872864177.

Perls, Fritz (1969). In and Out of the Garbage Pail. Gestalt Journal Press. ISBN 978-0939266173.

Wilson, Carol Ann (2009). Still Point of the Turning World: The Life of Gia-fu Feng. Amber Lotus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60237-296-2.

- 1919 births

- 1985 deaths

- American writers of Chinese descent

- Beat Generation people

- Chinese–English translators

- 20th-century Chinese translators

- Writers from Shanghai

- 20th-century American translators

- People from Manitou Springs, Colorado

- National Southwestern Associated University alumni

- Chinese emigrants to the United States