Deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being considered to be sacred and worthy of worship due to having authority over the universe, nature or human life.[1][2] The Oxford Dictionary of English defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine.[3] C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater than those of ordinary humans, but who interacts with humans, positively or negatively, in ways that carry humans to new levels of consciousness, beyond the grounded preoccupations of ordinary life".[4]

Religions can be categorized by how many deities they worship. Monotheistic religions accept only one deity (predominantly referred to as "God"),[5][6] whereas polytheistic religions accept multiple deities.[7] Henotheistic religions accept one supreme deity without denying other deities, considering them as aspects of the same divine principle.[8][9] Nontheistic religions deny any supreme eternal creator deity, but may accept a pantheon of deities which live, die and may be reborn like any other being.[10]: 35–37 [11]: 357–358

Although most monotheistic religions traditionally envision their god as omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, omnibenevolent, and eternal,[12][13] none of these qualities are essential to the definition of a "deity"[14][15][16] and various cultures have conceptualized their deities differently.[14][15] Monotheistic religions typically refer to their god in masculine terms,[17][18]: 96 while other religions refer to their deities in a variety of ways—male, female, hermaphroditic, or genderless.[19][20][21]

Many cultures—including the ancient Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Germanic peoples—have personified natural phenomena, variously as either deliberate causes or effects.[22][23][24] Some Avestan and Vedic deities were viewed as ethical concepts.[22][23] In Indian religions, deities have been envisioned as manifesting within the temple of every living being's body, as sensory organs and mind.[25][26][27] Deities are envisioned as a form of existence (Saṃsāra) after rebirth, for human beings who gain merit through an ethical life, where they become guardian deities and live blissfully in heaven, but are also subject to death when their merit is lost.[10]: 35–38 [11]: 356–359

Etymology

[edit]The English language word deity derives from Old French deité,[28][page needed] the Latin deitatem (nominative deitas) or "divine nature", coined by Augustine of Hippo from deus ("god"). Deus is related through a common Proto-Indo-European (PIE) origin to *deiwos.[29] This root yields the ancient Indian word Deva meaning "to gleam, a shining one", from *div- "to shine", as well as Greek dios "divine" and Zeus; and Latin deus "god" (Old Latin deivos).[30][31][32]: 230–31 Deva is masculine, and the related feminine equivalent is devi.[33]: 496 Etymologically, the cognates of Devi are Latin dea and Greek thea.[34] In Old Persian, daiva- means "demon, evil god",[31] while in Sanskrit it means the opposite, referring to the "heavenly, divine, terrestrial things of high excellence, exalted, shining ones".[33]: 496 [35][36]

The closely linked term "god" refers to "supreme being, deity", according to Douglas Harper,[37] and is derived from Proto-Germanic *guthan, from PIE *ghut-, which means "that which is invoked".[32]: 230–231 Guth in the Irish language means "voice". The term *ghut- is also the source of Old Church Slavonic zovo ("to call"), Sanskrit huta- ("invoked", an epithet of Indra), from the root *gheu(e)- ("to call, invoke."),[37]

An alternate etymology for the term "god" comes from the Proto-Germanic Gaut, which traces it to the PIE root *ghu-to- ("poured"), derived from the root *gheu- ("to pour, pour a libation"). The term *gheu- is also the source of the Greek khein "to pour".[37] Originally the word "god" and its other Germanic cognates were neuter nouns but shifted to being generally masculine under the influence of Christianity in which the god is typically seen as male.[32]: 230–231 [37] In contrast, all ancient Indo-European cultures and mythologies recognized both masculine and feminine deities.[36]

Definitions

[edit]

There is no universally accepted consensus on what a deity is, and concepts of deities vary considerably across cultures.[18]: 69–74 [40] Huw Owen states that the term "deity or god or its equivalent in other languages" has a bewildering range of meanings and significance.[41]: vii–ix It has ranged from "infinite transcendent being who created and lords over the universe" (God), to a "finite entity or experience, with special significance or which evokes a special feeling" (god), to "a concept in religious or philosophical context that relates to nature or magnified beings or a supra-mundane realm", to "numerous other usages".[41]: vii–ix

A deity is typically conceptualized as a supernatural or divine concept, manifesting in ideas and knowledge, in a form that combines excellence in some or all aspects, wrestling with weakness and questions in other aspects, heroic in outlook and actions, yet tied up with emotions and desires.[42][43] In other cases, the deity is a principle or reality such as the idea of "soul". The Upanishads of Hinduism, for example, characterize Atman (soul, self) as deva (deity), thereby asserting that the deva and eternal supreme principle (Brahman) is part of every living creature, that this soul is spiritual and divine, and that to realize self-knowledge is to know the supreme.[44][45][46]

Theism is the belief in the existence of one or more deities.[47][48] Polytheism is the belief in and worship of multiple deities,[49] which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, with accompanying rituals.[49] In most polytheistic religions, the different gods and goddesses are representations of forces of nature or ancestral principles, and can be viewed either as autonomous or as aspects or emanations of a creator God or transcendental absolute principle (monistic theologies), which manifests immanently in nature.[49] Henotheism accepts the existence of more than one deity, but considers all deities as equivalent representations or aspects of the same divine principle, the highest.[9][50][8][51] Monolatry is the belief that many deities exist, but that only one of these deities may be validly worshipped.[52][53]

Monotheism is the belief that only one deity exists.[54][55][56][57][58][59][60][excessive citations] A monotheistic deity, known as "God", is usually described as omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, omnibenevolent and eternal.[61] However, not all deities have been regarded this way[14][16][62][63] and an entity does not need to be almighty, omnipresent, omniscient, omnibenevolent or eternal to qualify as a deity.[14][16][62]

Deism is the belief that only one deity exists, who created the universe, but does not usually intervene in the resulting world.[64][65][66][page needed] Deism was particularly popular among western intellectuals during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[67][68] Pantheism is the belief that the universe itself is God[38] or that everything composes an all-encompassing, immanent deity.[39] Pandeism is an intermediate position between these, proposing that the creator became a pantheistic universe.[69] Panentheism is the belief that divinity pervades the universe, but that it also transcends the universe.[70] Agnosticism is the position that it is impossible to know for certain whether a deity of any kind exists.[71][72][73] Atheism is the non-belief in the existence of any deity.[74]

Prehistoric

[edit]

Scholars infer the probable existence of deities in the prehistoric period from inscriptions and prehistoric arts such as cave drawings, but it is unclear what these sketches and paintings are and why they were made.[77] Some engravings or sketches show animals, hunters or rituals.[78] It was once common for archaeologists to interpret virtually every prehistoric female figurine as a representation of a single, primordial goddess, the ancestor of historically attested goddesses such as Inanna, Ishtar, Astarte, Cybele, and Aphrodite;[79] this approach has now generally been discredited.[79] Modern archaeologists now generally recognize that it is impossible to conclusively identify any prehistoric figurines as representations of any kind of deities, let alone goddesses.[79] Nonetheless, it is possible to evaluate ancient representations on a case-by-case basis and rate them on how likely they are to represent deities.[79] The Venus of Willendorf, a female figurine found in Europe and dated to about 25,000 BCE has been interpreted by some as an exemplar of a prehistoric female deity.[78] A number of probable representations of deities have been discovered at 'Ain Ghazal[79] and the works of art uncovered at Çatalhöyük reveal references to what is probably a complex mythology.[79]

Religions and cultures

[edit]Sub-Saharan African

[edit]

Diverse African cultures developed theology and concepts of deities over their history. In Nigeria and neighboring West African countries, for example, two prominent deities (locally called Òrìṣà)[80] are found in the Yoruba religion, namely the god Ogun and the goddess Osun.[80] Ogun is the primordial masculine deity as well as the archdivinity and guardian of occupations such as tools making and use, metal working, hunting, war, protection and ascertaining equity and justice.[81][82] Osun is an equally powerful primordial feminine deity and a multidimensional guardian of fertility, water, maternal, health, social relations, love and peace.[80] Ogun and Osun traditions were brought into the Americas on slave ships. They were preserved by the Africans in their plantation communities, and their festivals continue to be observed.[80][81]

In Southern African cultures, a similar masculine-feminine deity combination has appeared in other forms, particularly as the Moon and Sun deities.[83] One Southern African cosmology consists of Hieseba or Xuba (deity, god), Gaune (evil spirits) and Khuene (people). The Hieseba includes Nladiba (male, creator sky god) and Nladisara (females, Nladiba's two wives). The Sun (female) and the Moon (male) deities are viewed as offspring of Nladiba and two Nladisara. The Sun and Moon are viewed as manifestations of the supreme deity, and worship is timed and directed to them.[84] In other African cultures the Sun is seen as male, while the Moon is female, both symbols of the godhead.[85]: 199–120 In Zimbabwe, the supreme deity is androgynous with male-female aspects, envisioned as the giver of rain, treated simultaneously as the god of darkness and light and is called Mwari Shona.[85]: 89 In the Lake Victoria region, the term for a deity is Lubaale, or alternatively Jok.[86]

Ancient Near Eastern

[edit]Egyptian

[edit]

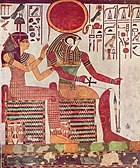

Ancient Egyptian culture revered numerous deities. Egyptian records and inscriptions list the names of many whose nature is unknown and make vague references to other unnamed deities.[88]: 73 Egyptologist James P. Allen estimates that more than 1,400 deities are named in Egyptian texts,[89] whereas Christian Leitz offers an estimate of "thousands upon thousands" of Egyptian deities.[90]: 393–394 Their terms for deities were nṯr (god), and feminine nṯrt (goddess);[91]: 42 however, these terms may also have applied to any being – spirits and deceased human beings, but not demons – who in some way were outside the sphere of everyday life.[92]: 216 [91]: 62 Egyptian deities typically had an associated cult, role and mythologies.[92]: 7–8, 83

Around 200 deities are prominent in the Pyramid texts and ancient temples of Egypt, many zoomorphic. Among these, were Min (fertility god), Neith (creator goddess), Anubis, Atum, Bes, Horus, Isis, Ra, Meretseger, Nut, Osiris, Shu, Sia and Thoth.[87]: 11–12 Most Egyptian deities represented natural phenomenon, physical objects or social aspects of life, as hidden immanent forces within these phenomena.[93][94] The deity Shu, for example represented air; the goddess Meretseger represented parts of the earth, and the god Sia represented the abstract powers of perception.[95]: 91, 147 Deities such as Ra and Osiris were associated with the judgement of the dead and their care during the afterlife.[87]: 26–28 Major gods often had multiple roles and were involved in multiple phenomena.[95]: 85–86

The first written evidence of deities are from early 3rd millennium BCE, likely emerging from prehistoric beliefs.[96] However, deities became systematized and sophisticated after the formation of an Egyptian state under the Pharaohs and their treatment as sacred kings who had exclusive rights to interact with the gods, in the later part of the 3rd millennium BCE.[97][88]: 12–15 Through the early centuries of the common era, as Egyptians interacted and traded with neighboring cultures, foreign deities were adopted and venerated.[98][90]: 160

Levantine

[edit]

The ancient Canaanites were polytheists who believed in a pantheon of deities,[99][100][101] the chief of whom was the god El, who ruled alongside his consort Asherah and their seventy sons.[99]: 22–24 [100][101] Baal was the god of storm, rain, vegetation and fertility,[99]: 68–127 while his consort Anat was the goddess of war[99]: 131, 137–139 and Astarte, the West Semitic equivalent to Ishtar, was the goddess of love.[99]: 146–149 The people of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah originally believed in these deities,[99][101][102] alongside their own national god Yahweh.[103][104] El later became syncretized with Yahweh, who took over El's role as the head of the pantheon,[99]: 13–17 with Asherah as his divine consort[105]: 45 [99]: 146 and the "sons of El" as his offspring.[99]: 22–24 During the later years of the Kingdom of Judah, a monolatristic faction rose to power insisting that only Yahweh was fit to be worshipped by the people of Judah.[99]: 229–233 Monolatry became enforced during the reforms of King Josiah in 621 BCE.[99]: 229 Finally, during the national crisis of the Babylonian captivity, some Judahites began to teach that deities aside from Yahweh were not just unfit to be worshipped, but did not exist.[106][41]: 4 The "sons of El" were demoted from deities to angels.[99]: 22

Mesopotamian

[edit]Ancient Mesopotamian culture in southern Iraq had numerous dingir (deities, gods and goddesses).[18]: 69–74 [40] Mesopotamian deities were almost exclusively anthropomorphic.[107]: 93 [18]: 69–74 [108] They were thought to possess extraordinary powers[107]: 93 and were often envisioned as being of tremendous physical size.[107]: 93 They were generally immortal,[107]: 93 but a few of them, particularly Dumuzid, Geshtinanna, and Gugalanna were said to have either died or visited the underworld.[107]: 93 Both male and female deities were widely venerated.[107]: 93

In the Sumerian pantheon, deities had multiple functions, which included presiding over procreation, rains, irrigation, agriculture, destiny, and justice.[18]: 69–74 The gods were fed, clothed, entertained, and worshipped to prevent natural catastrophes as well as to prevent social chaos such as pillaging, rape, or atrocities.[18]: 69–74 [109]: 186 [107]: 93 Many of the Sumerian deities were patron guardians of city-states.[109]

The most important deities in the Sumerian pantheon were known as the Anunnaki,[110] and included deities known as the "seven gods who decree": An, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu and Inanna.[110] After the conquest of Sumer by Sargon of Akkad, many Sumerian deities were syncretized with East Semitic ones.[109] The goddess Inanna, syncretized with the East Semitic Ishtar, became popular,[111][112]: xviii, xv [109]: 182 [107]: 106–09 with temples across Mesopotamia.[113][107]: 106–09

The Mesopotamian mythology of the first millennium BCE treated Anšar (later Aššur) and Kišar as primordial deities.[114] Marduk was a significant god among the Babylonians. He rose from an obscure deity of the third millennium BCE to become one of the most important deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon of the first millennium BCE. The Babylonians worshipped Marduk as creator of heaven, earth and humankind, and as their national god.[18]: 62, 73 [115] Marduk's iconography is zoomorphic and is most often found in Middle Eastern archaeological remains depicted as a "snake-dragon" or a "human-animal hybrid".[116][117][118]

Indo-European

[edit]Germanic

[edit]

In Germanic languages, the terms cognate with 'god' such as Old English: god and Old Norse: guð were originally neuter but became masculine, as in modern Germanic languages, after Christianisation due their use in referring to the Christian god.[119]

In Norse mythology, Æsir (singular áss or ǫ́ss) are the principal group of gods,[120] while the term ásynjur (singular ásynja) refers specifically to the female Æsir.[121] These terms, states John Lindow, may be ultimately rooted in the Indo-European root for "breath" (as in "life giving force"), and are cognate with Old English: os (a heathen god) and Gothic: anses.[122]: 49–50

Another group of deities found in Norse mythology are termed as Vanir, and are associated with fertility. The Æsir and the Vanir went to war, according to the Nordic sources. The account in Ynglinga saga describes the Æsir–Vanir War ending in truce and ultimate reconciliation of the two into a single group of gods, after both sides chose peace, exchanged ambassadors (hostages),[123]: 181 and intermarried.[122]: 52–53 [124]

The Norse mythology describes the cooperation after the war, as well as differences between the Æsir and the Vanir which were considered scandalous by the other side.[123]: 181 The goddess Freyja of the Vanir taught magic to the Æsir, while the two sides discover that while Æsir forbid mating between siblings, Vanir accepted such mating.[123]: 181 [125][126]

Temples hosting images of Germanic gods (such as Thor, Odin and Freyr), as well as pagan worship rituals, continued in Scandinavia into the 12th century, according to historical records. It has been proposed that over time, Christian equivalents were substituted for the Germanic deities to help suppress paganism as part of the Christianisation of the Germanic peoples.[123]: 187–188 Worship of the Germanic gods has been revived in the modern period as part of the new religious movement of Heathenry.[127]

Greek

[edit]The ancient Greeks revered both gods and goddesses.[128] These continued to be revered through the early centuries of the common era, and many of the Greek deities inspired and were adopted as part of much larger pantheon of Roman deities.[129]: 91–97 The Greek religion was polytheistic, but had no centralized church, nor any sacred texts.[129]: 91–97 The deities were largely associated with myths and they represented natural phenomena or aspects of human behavior.[128][129]: 91–97

Several Greek deities probably trace back to more ancient Indo-European traditions, since the gods and goddesses found in distant cultures are mythologically comparable and are cognates.[32]: 230–231 [130]: 15–19 Eos, the Greek goddess of the dawn, for instance, is cognate to Indic Ushas, Roman Aurora and Latvian Auseklis.[32]: 230–232 Zeus, the Greek king of gods, is cognate to Latin Iūpiter, Old German Ziu, and Indic Dyaus, with whom he shares similar mythologies.[32]: 230–232 [131] Other deities, such as Aphrodite, originated from the Near East.[132][133][134][135]

Greek deities varied locally, but many shared panhellenic themes, celebrated similar festivals, rites, and ritual grammar.[136] The most important deities in the Greek pantheon were the Twelve Olympians: Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Hermes, Demeter, Dionysus, Hephaestus, and Ares.[130]: 125–170 Other important Greek deities included Hestia, Hades and Heracles.[129]: 96–97 These deities later inspired the Dii Consentes galaxy of Roman deities.[129]: 96–97

Besides the Olympians, the Greeks also worshipped various local deities.[130]: 170–181 [137] Among these were the goat-legged god Pan (the guardian of shepherds and their flocks), Nymphs (nature spirits associated with particular landforms), Naiads (who dwelled in springs), Dryads (who were spirits of the trees), Nereids (who inhabited the sea), river gods, satyrs (a class of lustful male nature spirits), and others. The dark powers of the underworld were represented by the Erinyes (or Furies), said to pursue those guilty of crimes against blood-relatives.[137]

The Greek deities, like those in many other Indo-European traditions, were anthropomorphic. Walter Burkert describes them as "persons, not abstractions, ideas or concepts".[130]: 182 They had fantastic abilities and powers; each had some unique expertise and, in some aspects, a specific and flawed personality.[138]: 52 They were not omnipotent and could be injured in some circumstances.[139] Greek deities led to cults, were used politically and inspired votive offerings for favors such as bountiful crops, healthy family, victory in war, or peace for a loved one recently deceased.[129]: 94–95 [140]

Roman

[edit]

The Roman pantheon had numerous deities, both Greek and non-Greek.[129]: 96–97 The more famed deities, found in the mythologies and the 2nd millennium CE European arts, have been the anthropomorphic deities syncretized with the Greek deities. These include the six gods and six goddesses: Venus, Apollo, Mars, Diana, Minerva, Ceres, Vulcan, Juno, Mercury, Vesta, Neptune, Jupiter (Jove, Zeus); as well Bacchus, Pluto and Hercules.[129]: 96–97 [141] The non-Greek major deities include Janus, Fortuna, Vesta, Quirinus and Tellus (mother goddess, probably most ancient).[129]: 96–97 [142] Some of the non-Greek deities had likely origins in more ancient European culture such as the ancient Germanic religion, while others may have been borrowed, for political reasons, from neighboring trade centers such as those in the Minoan or ancient Egyptian civilization.[143][144][145]

The Roman deities, in a manner similar to the ancient Greeks, inspired community festivals, rituals and sacrifices led by flamines (priests, pontifs), but priestesses (Vestal Virgins) were also held in high esteem for maintaining sacred fire used in the votive rituals for deities.[129]: 100–101 Deities were also maintained in home shrines (lararium), such as Hestia honored in homes as the goddess of fire hearth.[129]: 100–101 [146] This Roman religion held reverence for sacred fire, and this is also found in Hebrew culture (Leviticus 6), Vedic culture's Homa, ancient Greeks and other cultures.[146]

Ancient Roman scholars such as Varro and Cicero wrote treatises on the nature of gods of their times.[147] Varro stated, in his Antiquitates Rerum Divinarum, that it is the superstitious man who fears the gods, while the truly religious person venerates them as parents.[147] Cicero, in his Academica, praised Varro for this and other insights.[147] According to Varro, there have been three accounts of deities in the Roman society: the mythical account created by poets for theatre and entertainment, the civil account used by people for veneration as well as by the city, and the natural account created by the philosophers.[148] The best state is, adds Varro, where the civil theology combines the poetic mythical account with the philosopher's.[148] The Roman deities continued to be revered in Europe through the era of Constantine, and past 313 CE when he issued the Edict of Toleration.[138]: 118–120

Native American

[edit]Inca

[edit]The Inca culture has believed in Viracocha (also called Pachacutec) as the creator deity.[149]: 27–30 [150]: 726–729 Viracocha has been an abstract deity to Inca culture, one who existed before he created space and time.[151] All other deities of the Inca people have corresponded to elements of nature.[149][150]: 726–729 Of these, the most important ones have been Inti (sun deity) responsible for agricultural prosperity and as the father of the first Inca king, and Mama Qucha the goddess of the sea, lakes, rivers and waters.[149] Inti in some mythologies is the son of Viracocha and Mama Qucha.[149][152]

Inca Sun deity festival

Oh creator and Sun and Thunder,

be forever copious,

do not make us old,

let all things be at peace,

multiply the people,

and let there be food,

and let all things be fruitful.

—Inti Raymi prayers[153]

Inca people have revered many male and female deities. Among the feminine deities have been Mama Kuka (goddess of joy), Mama Ch'aska (goddess of dawn), Mama Allpa (goddess of harvest and earth, sometimes called Mama Pacha or Pachamama), Mama Killa (moon goddess) and Mama Sara (goddess of grain).[152][149]: 31–32 During and after the imposition of Christianity during Spanish colonialism, the Inca people retained their original beliefs in deities through syncretism, where they overlay the Christian God and teachings over their original beliefs and practices.[154][155][156] The male deity Inti became accepted as the Christian God, but the Andean rituals centered around Inca deities have been retained and continued thereafter into the modern era by the Inca people.[156][157]

Maya and Aztec

[edit]In Maya culture, Kukulkan has been the supreme creator deity, also revered as the god of reincarnation, water, fertility and wind.[150]: 797–798 The Maya people built step pyramid temples to honor Kukulkan, aligning them to the Sun's position on the spring equinox.[150]: 843–844 Other deities found at Maya archaeological sites include Xib Chac—the benevolent male rain deity, and Ixchel—the benevolent female earth, weaving and pregnancy goddess.[150]: 843–844 The Maya calendar had 18 months, each with 20 days (and five unlucky days of Uayeb); each month had a presiding deity, who inspired social rituals, special trading markets and community festivals.[157]

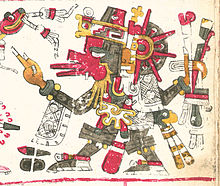

A deity with aspects similar to Kulkulkan in the Aztec culture has been called Quetzalcoatl.[150]: 797–798 However, states Timothy Insoll, the Aztec ideas of deity remain poorly understood. What has been assumed is based on what was constructed by Christian missionaries. The deity concept was likely more complex than these historical records.[158] In Aztec culture, there were hundred of deities, but many were henotheistic incarnations of one another (similar to the avatar concept of Hinduism). Unlike Hinduism and other cultures, Aztec deities were usually not anthropomorphic, and were instead zoomorphic or hybrid icons associated with spirits, natural phenomena or forces.[158][159] The Aztec deities were often represented through ceramic figurines, revered in home shrines.[158][160]

Polynesian

[edit]

The Polynesian people developed a theology centered on numerous deities, with clusters of islands having different names for the same idea. There are great deities found across the Pacific Ocean. Some deities are found widely, and there are many local deities whose worship is limited to one or a few islands or sometimes to isolated villages on the same island.[161]: 5–6

The Māori people, of what is now New Zealand, called the supreme being as Io, who is also referred elsewhere as Iho-Iho, Io-Mataaho, Io Nui, Te Io Ora, Io Matua Te Kora among other names.[162]: 239 The Io deity has been revered as the original uncreated creator, with power of life, with nothing outside or beyond him.[162]: 239 Other deities in the Polynesian pantheon include Tangaloa (god who created men),[161]: 37–38 La'a Maomao (god of winds), Tu-Matauenga or Ku (god of war), Tu-Metua (mother goddess), Kane (god of procreation) and Rangi (sky god father).[162]: 261, 284, 399, 476

The Polynesian deities have been part of a sophisticated theology, addressing questions of creation, the nature of existence, guardians in daily lives as well as during wars, natural phenomena, good and evil spirits, priestly rituals, as well as linked to the journey of the souls of the dead.[161]: 6–14, 37–38, 113, 323

Abrahamic

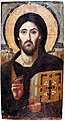

[edit]Christianity

[edit]

Christianity is a monotheistic religion in which most mainstream congregations and denominations accept the concept of the Holy Trinity.[163]: 233–234 Modern orthodox Christians believe that the Trinity is composed of three equal, cosubstantial persons: God the Father, God the Son, and the Holy Spirit.[163]: 233–234 The first person to describe the persons of the Trinity as homooúsios (ὁμοούσιος; "of the same substance") was the Church Father Origen.[164] Although most early Christian theologians (including Origen) were Subordinationists,[165] who believed that the Father was superior to the Son and the Son superior to the Holy Spirit,[164][166][167] this belief was condemned as heretical by the First Council of Nicaea in the fourth century, which declared that all three persons of the Trinity are equal.[165] Christians regard the universe as an element in God's actualization[163]: 273 and the Holy Spirit is seen as the divine essence that is "the unity and relation of the Father and the Son".[163]: 273 According to George Hunsinger, the doctrine of the Trinity justifies worship in a Church, wherein Jesus Christ is deemed to be a full deity with the Christian cross as his icon.[163]: 296

The theological examination of Jesus Christ, of divine grace in incarnation, his non-transferability and completeness has been a historic topic. For example, the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE declared that in "one person Jesus Christ, fullness of deity and fullness of humanity are united, the union of the natures being such that they can neither be divided nor confused".[168] Jesus Christ, according to the New Testament, is the self-disclosure of the one, true God, both in his teaching and in his person; Christ, in Christian faith, is considered the incarnation of God.[41]: 4, 29 [169][170]

Islam

[edit]Ilah, ʾIlāh (Arabic: إله; plural: آلهة ʾālihah), is an Arabic word meaning "god".[171][172] It appears in the name of the monotheistic god of Islam as Allah (al-Lāh).[173][174][175] which literally means "the god" in Arabic.[171][172] Islam is strictly monotheistic[176] and the first statement of the shahada, or Muslim confession of faith, is that "there is no ʾilāh (deity) but Allah (God)",[177] who is perfectly unified and utterly indivisible.[176][177][178]

The term Allah is used by Muslims for God. The Persian word Khuda (Persian: خدا) can be translated as god, lord or king, and is also used today to refer to God in Islam by Persian, Urdu, Tat and Kurdish speakers. The Turkic word for god is Tengri; it exists as Tanrı in Turkish.

Judaism

[edit]

Judaism affirms the existence of one God (Yahweh, or YHWH), who is not abstract, but He who revealed himself throughout Jewish history particularly during the Exodus and the Exile.[41]: 4 Judaism reflects a monotheism that gradually arose, was affirmed with certainty in the sixth century "Second Isaiah", and has ever since been the axiomatic basis of its theology.[41]: 4

The classical presentation of Judaism has been as a monotheistic faith that rejected deities and related idolatry.[179] However, states Breslauer, modern scholarship suggests that idolatry was not absent in biblical faith, and it resurfaced multiple times in Jewish religious life.[179] The rabbinic texts and other secondary Jewish literature suggest worship of material objects and natural phenomena through the medieval era, while the core teachings of Judaism maintained monotheism.[179][180][page needed]

According to Aryeh Kaplan, God is always referred to as "He" in Judaism, "not to imply that the concept of sex or gender applies to God", but because "there is no neuter in the Hebrew language, and the Hebrew word for God is a masculine noun" as he "is an active rather than a passive creative force".[181]

Mandaeism

[edit]In Mandaeism, Hayyi Rabbi (lit=The Great Life), or 'The Great Living God',[182] is the supreme God from which all things emanate. He is also known as 'The First Life', since during the creation of the material world, Yushamin emanated from Hayyi Rabbi as the "Second Life."[183] "The principles of the Mandaean doctrine: the belief of the only one great God, Hayyi Rabbi, to whom all absolute properties belong; He created all the worlds, formed the soul through his power, and placed it by means of angels into the human body. So He created Adam and Eve, the first man and woman."[184] Mandaeans recognize God to be the eternal, creator of all, the one and only in domination who has no partner.[185]

Asian

[edit]Anitism

[edit]Anitism, composed of an array of indigenous religions from the Philippines, has multiple pantheons of deities. There are more than a hundred different ethnic groups in the Philippines, each having their own supreme deity or deities. Each supreme deity or deities normally rules over a pantheon of deities, contributing to the sheer diversity of deities in Anitism.[186]The supreme deity or deities of ethnic groups are almost always the most notable.[186]

For example, Bathala is the Tagalog supreme deity,[187] Mangechay is the Kapampangan supreme deity,[188] Malayari is the Sambal supreme deity,[189] Melu is the Blaan supreme deity,[190] Kaptan is the Bisaya supreme deity,[191] and so on.

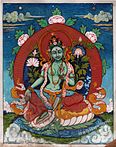

Buddhism

[edit]Although Buddhists do not believe in a creator deity,[192] deities are an essential part of Buddhist teachings about cosmology, rebirth, and saṃsāra.[192] Buddhist deities (such as devas and bodhisattvas) are believed to reside in a pleasant, heavenly realm within Buddhist cosmology, which is typically subdivided into twenty six sub-realms.[193][192][10]: 35

Devas are numerous, but they are still mortal;[193] they live in the heavenly realm, then die and are reborn like all other beings.[193] A rebirth in the heavenly realm is believed to be the result of leading an ethical life and accumulating very good karma.[193] A deva does not need to work, and is able to enjoy in the heavenly realm all pleasures found on Earth. However, the pleasures of this realm lead to attachment (upādāna), lack of spiritual pursuits, and therefore no nirvana.[10]: 37 Nonetheless, according to Kevin Trainor, the vast majority of Buddhist lay people in countries practicing Theravada have historically pursued Buddhist rituals and practices because they are motivated by their potential rebirth into the deva realm.[193][194][195] The deva realm in Buddhist practice in Southeast Asia and East Asia, states Keown, include gods found in Hindu traditions such as Indra and Brahma, and concepts in Hindu cosmology such as Mount Meru.[10]: 37–38

Mahayana Buddhism also includes different kinds of deities, such as numerous Buddhas, bodhisattvas and fierce deities.

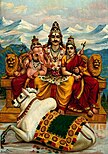

Hinduism

[edit]The concept of God varies in Hinduism, it being a diverse system of thought with beliefs spanning henotheism, monotheism, polytheism, panentheism, pantheism and monism among others.[196][197]

In the ancient Vedic texts of Hinduism, a deity is often referred to as Deva (god) or Devi (goddess).[33]: 496 [35] The root of these terms mean "heavenly, divine, anything of excellence".[33]: 492 [35] Deva is masculine, and the related feminine equivalent is devi. In the earliest Vedic literature, all supernatural beings are called Asuras.[198]: 5–11, 22, 99–102 [33]: 121 Over time, those with a benevolent nature become deities and are referred to as Sura, Deva or Devi.[198]: 2–6 [199]

Devas or deities in Hindu texts differ from Greek or Roman theodicy, states Ray Billington, because many Hindu traditions believe that a human being has the potential to be reborn as a deva (or devi), by living an ethical life and building up saintly karma.[200] Such a deva enjoys heavenly bliss, till the merit runs out, and then the soul is reborn again into Saṃsāra. Thus deities are henotheistic manifestations, embodiments and consequence of the virtuous, the noble, the saint-like living in many Hindu traditions.[200]

Shinto

[edit]Shinto is polytheistic, involving the veneration of many deities known as kami,[201] or sometimes as jingi.[202] In Japanese, no distinction is made here between singular and plural, and hence the term kami refers both to individual kami and the collective group of kami.[203] Although lacking a direct English translation,[204] the term kami has sometimes been rendered as "god" or "spirit".[205] The historian of religion Joseph Kitagawa deemed these English translations "quite unsatisfactory and misleading",[206] and various scholars urge against translating kami into English.[207] In Japanese, it is often said that there are eight million kami, a term which connotes an infinite number,[208] and Shinto practitioners believe that they are present everywhere.[209] They are not regarded as omnipotent, omniscient, or necessarily immortal.[210]

Taoism

[edit]Taoism is polytheistic religion. The gods and immortals (神仙) believed in by Taoism can be roughly divided into two categories, namely "gods" and "xian". "Gods" refers to deities and there are many kinds, that is, heaven gods/celestials (天神), earth spirits (地祇), wuling (物灵, animism, the spirit of all things), netherworld gods (地府神灵), gods of human body (人体之神), gods of human ghost (人鬼之神)etc. Among these "gods" such as heaven gods/celestials (天神), earth spirits(地祇), netherworld gods(阴府神灵), gods of human body (人体之神) exist innately."Xian" is acquired the cultivation of the Tao,persons with vast supernatural powers, unpredictable changes and immortality.[211]

Jainism

[edit]

Jainism does not believe in a creator, omnipotent, omniscient, eternal God; however, the cosmology of Jainism incorporates a meaningful causality-driven reality, including four realms of existence (gati), one of them being deva (celestial beings, gods).[11]: 351–357 A human being can choose and live an ethical life, such as being non-violent (ahimsa) against all living beings, and thereby gain merit and be reborn as deva.[11]: 357–358 [212]

Jain texts reject a trans-cosmic God, one who stands outside of the universe and lords over it, but they state that the world is full of devas who are in human-image with sensory organs, with the power of reason, conscious, compassionate and with finite life.[11]: 356–357 Jainism believes in the existence of the soul (Self, atman) and considers it to have "god-quality", whose knowledge and liberation is the ultimate spiritual goal in both religions. Jains also believe that the spiritual nobleness of perfected souls (Jina) and devas make them worship-worthy beings, with powers of guardianship and guidance to better karma. In Jain temples or festivals, the Jinas and Devas are revered.[11]: 356–357 [213]

Zoroastrianism

[edit]

Ahura Mazda (/əˌhʊrəˌmæzdə/);[214] is the Avestan name for the creator and sole God of Zoroastrianism.[215] The literal meaning of the word Ahura is "mighty" or "lord" and Mazda is wisdom.[215] Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism, taught that Ahura Mazda is the most powerful being in all of the existence[216] and the only deity who is worthy of the highest veneration.[216] Nonetheless, Ahura Mazda is not omnipotent because his evil twin brother Angra Mainyu is nearly as powerful as him.[216] Zoroaster taught that the daevas were evil spirits created by Angra Mainyu to sow evil in the world[216] and that all people must choose between the goodness of Ahura Mazda and the evil of Angra Mainyu.[216] According to Zoroaster, Ahura Mazda will eventually defeat Angra Mainyu and good will triumph over evil once and for all.[216] Ahura Mazda was the most important deity in the ancient Achaemenid Empire.[217] He was originally represented anthropomorphically,[215] but, by the end of the Sasanian Empire, Zoroastrianism had become fully aniconic.[215]

Skeptical interpretations

[edit]

Attempts to rationally explain belief in deities extend all the way back to ancient Greece.[130]: 311–317 The Greek philosopher Democritus argued that the concept of deities arose when human beings observed natural phenomena such as lightning, solar eclipses, and the changing of the seasons.[130]: 311–317 Later, in the third century BCE, the scholar Euhemerus argued in his book Sacred History that the gods were originally flesh-and-blood mortal kings who were posthumously deified, and that religion was therefore the continuation of these kings' mortal reigns, a view now known as Euhemerism.[218] Sigmund Freud suggested that God concepts are a projection of one's father.[219]

A tendency to believe in deities and other supernatural beings may be an integral part of the human consciousness.[220][221][222][223]: 2–11 Children are naturally inclined to believe in supernatural entities such as gods, spirits, and demons, even without being introduced into a particular religious tradition.[223]: 2–11 Humans have an overactive agency detection system,[220][224][223]: 25–27 which has a tendency to conclude that events are caused by intelligent entities, even if they really are not.[220][224] This is a system which may have evolved to cope with threats to the survival of human ancestors:[220] in the wild, a person who perceived intelligent and potentially dangerous beings everywhere was more likely to survive than a person who failed to perceive actual threats, such as wild animals or human enemies.[220][223]: 2–11 Humans are also inclined to think teleologically and ascribe meaning and significance to their surroundings, a trait which may lead people to believe in a creator-deity.[225] This may have developed as a side effect of human social intelligence, the ability to discern what other people are thinking.[225]

Stories of encounters with supernatural beings are especially likely to be retold, passed on, and embellished due to their descriptions of standard ontological categories (person, artifact, animal, plant, natural object) with counterintuitive properties (humans that are invisible, houses that remember what happened in them, etc.).[226] As belief in deities spread, humans may have attributed anthropomorphic thought processes to them,[227] leading to the idea of leaving offerings to the gods and praying to them for assistance,[227] ideas which are seen in all cultures around the world.[220]

Sociologists of religion have proposed that the personality and characteristics of deities may reflect a culture's sense of self-esteem and that a culture projects its revered values into deities and in spiritual terms. The cherished, desired or sought human personality is congruent with the personality it defines to be gods.[219] Lonely and fearful societies tend to invent wrathful, violent, submission-seeking deities, while happier and secure societies tend to invent loving, non-violent, compassionate deities.[219] Émile Durkheim states that gods represent an extension of human social life to include supernatural beings. According to Matt Rossano, God concepts may be a means of enforcing morality and building more cooperative community groups.[228]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "god". Cambridge Dictionary.

- ^ "Definition of GOD". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus (2010). Oxford Dictionary of English (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Littleton, C. Scott (2005). Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology. New York: Marshall Cavendish. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-7614-7559-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Becking, Bob; Dijkstra, Meindert; Korpel, Marjo; Vriezen, Karel (2001). Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. London: New York. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-567-23212-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

The Christian tradition is, in imitation of Judaism, a monotheistic religion. This implies that believers accept the existence of only one God. Other deities either do not exist, are considered inferior, are seen as the product of human imagination, or are dismissed as remnants of a persistent paganism

- ^ Korte, Anne-Marie; Haardt, Maaike De (2009). The Boundaries of Monotheism: Interdisciplinary Explorations Into the Foundations of Western Monotheism. Brill. p. 9. ISBN 978-90-04-17316-3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Brown, Jeannine K. (2007). Scripture as Communication: Introducing Biblical Hermeneutics. Baker Academic. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8010-2788-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Taliaferro, Charles; Harrison, Victoria S.; Goetz, Stewart (2012). The Routledge Companion to Theism. Routledge. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-136-33823-6. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Reat, N. Ross; Perry, Edmund F. (1991). A World Theology: The Central Spiritual Reality of Humankind. Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–75. ISBN 978-0-521-33159-3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Keown, Damien (2013). Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction (New ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966383-5. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Bullivant, Stephen; Ruse, Michael (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Atheism. Oxford University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-19-964465-0. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Taliaferro, Charles; Marty, Elsa J. (2010). A Dictionary of Philosophy of Religion. A&C Black. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-1-4411-1197-5.

- ^ Trigger, Bruce G. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 473–474. ISBN 978-0-521-82245-9.

- ^ a b c d Hood, Robert Earl (1990). Must God Remain Greek?: Afro Cultures and God-talk. Fortress Press. pp. 128–29. ISBN 978-1-4514-1726-5.

African people may describe their deities as strong, but not omnipotent; wise but not omniscient; old but not eternal; great but not omnipresent (...)

- ^ a b Trigger, Bruce G. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 441–42. ISBN 978-0-521-82245-9.

[Historically...] people perceived far fewer differences between themselves and the gods than the adherents of modern monotheistic religions. Deities were not thought to be omniscient or omnipotent and were rarely believed to be changeless or eternal

- ^ a b c Murdoch, John (1861). English Translations of Select Tracts, Published in India: With an Introd. Containing Lists of the Tracts in Each Language. Graves. pp. 141–42.

We [monotheists] find by reason and revelation that God is omniscient, omnipotent, most holy, etc., but the Hindu deities possess none of those attributes. It is mentioned in their Shastras that their deities were all vanquished by the Asurs, while they fought in the heavens, and for fear of whom they left their abodes. This plainly shows that they are not omnipotent.

- ^ Kramarae, Cheris; Spender, Dale (2004). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women: Global Women's Issues and Knowledge. Routledge. p. 655. ISBN 978-1-135-96315-6. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g O'Brien, Julia M. (2014). Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Gender Studies. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-19-983699-4. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Bonnefoy, Yves (1992). Roman and European Mythologies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 274–75. ISBN 978-0-226-06455-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Pintchman, Tracy (2014). Seeking Mahadevi: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddess. SUNY Press. pp. 1–2, 19–20. ISBN 978-0-7914-9049-5. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Nathaniel (2016). To Be Cared For: The Power of Conversion and Foreignness of Belonging in an Indian Slum. University of California Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-520-96363-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Malandra, William W. (1983). An Introduction to Ancient Iranian Religion: Readings from the Avesta and the Achaemenid Inscriptions. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-8166-1115-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Fløistad, Guttorm (2010). Volume 10: Philosophy of Religion (1st ed.). Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media B.V. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-90-481-3527-1. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Potts, Daniel T. (1997). Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations (st ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 272–274. ISBN 978-0-8014-3339-9. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Potter, Karl H. (2014). The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 3: Advaita Vedanta up to Samkara and His Pupils. Princeton University Press. pp. 272–74. ISBN 978-1-4008-5651-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Olivelle, Patrick (2006). The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-536137-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine; York, Michael (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. London: Routledge. pp. 899–900. ISBN 978-1-135-18979-2. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Hoad, T. F. (2008). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Paw Prints. ISBN 978-1-4395-0571-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary – Deity". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary – Deva". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Online Etymology Dictionary – Zeus". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (1st ed.). London: Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Monier-Williams, Monier; Leumann, Ernst; Cappeller, Carl (2005). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages (Corrected ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3105-6. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Hawley, John Stratton; Wulff, Donna M. (1998). Devī: Goddesses of India (1st ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2, 18–21. ISBN 978-81-208-1491-2.

- ^ a b c Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2010). Survey of Hinduism, A: Third Edition (3rd ed.). SUNY Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-7914-8011-3.

- ^ a b Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world (Reprint ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 418–23. ISBN 978-0-19-928791-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Online Etymology Dictionary –\ God". Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b Pearsall, Judy (1998). The New Oxford Dictionary Of English (1st ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 1341. ISBN 978-0-19-861263-6.

- ^ a b Edwards, Paul (1967). Encyclopedia of Philosophy. New York: Macmillan. p. 34.

- ^ a b Strazny, Philipp (2013). Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Routledge. p. 1046. ISBN 978-1-135-45522-4. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Owen, Huw Parri (1971). Concepts of Deity. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-00093-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Gupta, Bina; Gupta, Professor of Philosophy and Director South Asia Language Area Center Bina (2012). An Introduction to Indian Philosophy: Perspectives on Reality, Knowledge, and Freedom. Routledge. pp. 21–25. ISBN 978-1-136-65310-0.

- ^ Gupta, Bina (2012). An Introduction to Indian Philosophy: Perspectives on Reality, Knowledge, and Freedom. Taylor & Francis. pp. 88–96. ISBN 978-1-136-65309-4.

- ^ Cohen, Signe (2008). Text and Authority in the Older Upaniṣads. Brill. pp. 40, 219–220, 243–244. ISBN 978-90-474-3363-7.

- ^ Fowler, Jeaneane (1997). Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 10, 17–18, 114–118, 132–133, 149. ISBN 978-1-898723-60-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Choon Kim, Yong; Freeman, David H. (1981). Oriental Thought: An Introduction to the Philosophical and Religious Thought of Asia. Totowa, NJ: Littlefield, Adams and Company. pp. 15–19. ISBN 978-0-8226-0365-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "the definition of theism". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "theism". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Libbrecht, Ulrich (2007). Within the Four Seas: Introduction to Comparative Philosophy. Peeters Publishers. p. 42. ISBN 978-90-429-1812-2.

- ^ Monotheism Archived 29 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine and Polytheism Archived 11 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica;

Louis Shores (1963). Collier's Encyclopedia: With Bibliography and Index. Crowell-Collier Publishing. p. 179. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2018., Quote: "While admitting a plurality of gods, henotheism at the same time affirms the paramount position of some one divine principle." - ^ Rangar Cline (2011). Ancient Angels: Conceptualizing Angeloi in the Roman Empire. Brill Academic. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-90-04-19453-3. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Eakin, Frank Jr. (1971). The Religion and Culture of Israel. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. p. 70., Quote: "Monolatry: The recognition of the existence of many gods but the consistent worship of one deity".

- ^ McConkie, Bruce R. (1979). Mormon Doctrine (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft. p. 351.

- ^ Monotheism. Hutchinson Encyclopedia (12th edition). p. 644.

- ^ Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Wainwright, William (2013). "Monotheism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Van Baaren, Theodorus P. "Monotheism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "monotheism". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "monotheism". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "monotheism". Cambridge English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted (editor). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ^ a b Beck, Guy L. (2005). Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 169, note 11. ISBN 978-0-7914-6415-1.

- ^ Williams, George M. (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology (Reprint ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 24–35. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ^ Manuel, Frank Edward; Pailin, David A. (1999). "Deism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

In general, Deism refers to what can be called natural religion, the acceptance of a certain body of religious knowledge that is inborn in every person or that can be acquired by the use of reason and the rejection of religious knowledge when it is acquired through either revelation or the teaching of any church.

- ^ Kohler, Kaufmann; Hirsch, Emil G. (1906). "DEISM". Jewish Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

DEISM: A system of belief which posits God's existence as the cause of all things, and admits His perfection, but rejects Divine revelation and government, proclaiming the all-sufficiency of natural laws.

- ^ Kurian, George Thomas (2008). The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-67060-6.

Deism is a rationalistic, critical approach to theism with an emphasis on natural theology. The Deists attempted to reduce religion to what they regarded as its most foundational, rationally justifiable elements. Deism is not, strictly speaking, the teaching that God wound up the world like a watch and let it run on its own, though that teaching was embraced by some within the movement.

- ^ Thomsett, Michael C. (2011). Heresy in the Roman Catholic Church: A History. Jefferson: McFarland & Co. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-7864-8539-0. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Ellen Judy; Reill, Peter Hanns (2004). Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment (Revised ed.). New York: Facts On File. pp. 146–158. ISBN 978-0-8160-5335-3. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Sal Restivo (2021). "The End of God and the Beginning of Inquiry". Society and the Death of God. Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-3676-3764-4. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

In the pandeism argument, an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God creates the universe and in the process becomes the universe and loses his powers to intervene in human affairs.

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin; Bromiley, Geoffrey William (2005). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8028-2416-5. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Borchert, Donald M. (2006). The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-02-865780-6.

In the most general use of the term, agnosticism is the view that we do not know whether there is a God or not.

- ^ Craig, Edward; Floridi, Luciano (1998). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-415-07310-3. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

In the popular sense, an agnostic is someone who neither believes nor disbelieves in God, whereas an atheist disbelieves in God. In the strict sense, however, agnosticism is the view that human reason is incapable of providing sufficient rational grounds to justify either the belief that God exists or the belief that God does not exist. In so far as one holds that our beliefs are rational only if they are sufficiently supported by human reason, the person who accepts the philosophical position of agnosticism will hold that neither the belief that God exists nor the belief that God does not exist is rational.

- ^ "agnostic, agnosticism". OED Online, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press. 2012.

agnostic. : A. n[oun]. :# A person who believes that nothing is known or can be known of immaterial things, especially of the existence or nature of God. :# In extended use: a person who is not persuaded by or committed to a particular point of view; a sceptic. Also: person of indeterminate ideology or conviction; an equivocator. : B. adj[ective]. :# Of or relating to the belief that the existence of anything beyond and behind material phenomena is unknown and (as far as can be judged) unknowable. Also: holding this belief. :# a. In extended use: not committed to or persuaded by a particular point of view; sceptical. Also: politically or ideologically unaligned; non-partisan, equivocal. agnosticism n. The doctrine or tenets of agnostics with regard to the existence of anything beyond and behind material phenomena or to knowledge of a First Cause or God.

- ^ Draper, Paul (2017). "Atheism and Agnosticism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 11 December 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Mellaart, James (1967). Catal Huyuk: A Neolithic Town in Anatolia. McGraw-Hill. p. 181.

- ^ A typical assessment: "A terracotta statuette of a seated (mother) goddess giving birth with each hand on the head of a leopard or panther from Çatalhöyük (dated around 6000 B.C.E.)" (Sarolta A. Takács, "Cybele and Catullus' Attis", in Eugene N. Lane, Cybele, Attis and related cults: essays in memory of M.J. Vermaseren 1996:376.

- ^ Brooks, Philip (2012). The Story of Prehistoric Peoples. New York: Rosen Central. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1-4488-4790-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Ruether, Rosemary Radford (2006). Goddesses and the Divine Feminine: A Western Religious History (1st ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-520-25005-5. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Lesure, Richard G. (2017). Insoll, Timothy (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 54–58. ISBN 978-0-19-967561-6. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Joseph M.; Sanford, Mei-Mei (2002). Osun across the Waters: A Yoruba Goddess in Africa and the Americas. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0-253-10863-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Barnes, Sandra T. (1997). Africa's Ogun: Old World and New (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. ix–x, 1–3, 59, 132–134, 199–200. ISBN 978-0-253-21083-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Juang, Richard M.; Morrissette, Noelle (2007). Africa and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 843–44. ISBN 978-1-85109-441-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Andrews, Tamra (2000). Dictionary of Nature Myths: Legends of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-19-513677-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Barnard, Alan (2001). Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–88, 153–155, 252–256. ISBN 978-0-521-42865-1. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Lynch, Patricia Ann; Roberts, Jeremy (2010). African Mythology, A to Z (2nd ed.). New York: Chelsea House. ISBN 978-1-4381-3133-7. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Makward, Edris; Lilleleht, Mark; Saber, Ahmed (2004). North-south Linkages and Connections in Continental and Diaspora African Literatures. Trenton, NJ: Africa World. pp. 302–04. ISBN 978-1-59221-157-9. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Pinch, Geraldine (2003). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- ^ Allen, James P. (July–August 1999). "Monotheism: The Egyptian Roots". Archaeology Odyssey. 2 (3): 44–54, 59.

- ^ a b Johnston, Sarah Iles (2004). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- ^ a b Baines, John (1996). Conceptions of God in Egypt: The One and the Many (Revised ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-1223-3.

- ^ a b Assmann, Jan; Lorton, David (2001). The Search for God in Ancient Egypt (1st ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3786-1.

- ^ Allen, James P. (2001). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-0-521-77483-3.

- ^ Dunand, Françoise; Zivie-Coche, Christiane; Lorton, David (2004). Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8014-8853-5.

- ^ a b Hart, George (2005). Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses (2nd ed.). Hoboken: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-02362-4.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A.H. (1999). Early dynastic Egypt (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-0-415-18633-9.

- ^ Traunecker, Claude; Lorton, David (2001). The Gods of Egypt (1st ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-8014-3834-9.

- ^ Shafer, Byron E.; Baines, John; Lesko, Leonard H.; Silverman, David P. (1991). Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths, and Personal Practice. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8014-9786-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Day, John (2002) [2000]. Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-6830-7.

- ^ a b Coogan, Michael D.; Smith, Mark S. (2012). Stories from Ancient Canaan (2nd ed.). Presbyterian Publishing Corp. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2.

- ^ a b c Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel (2nd ed.). Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3972-5.

- ^ Albertz, Rainer (1994). A History of Israelite Religion, Volume I: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-664-22719-7.

- ^ Miller, Patrick D (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-664-21262-9.

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism. A&C Black. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-567-55248-8.

- ^ Niehr, Herbert (1995). "The Rise of YHWH in Judahite and Israelite Religion". In Edelman, Diana Vikander (ed.). The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2.

- ^ Betz, Arnold Gottfried (2000). "Monotheism". In Freedman, David Noel; Myer, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. p. 917. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony; Rickards, Tessa (1998). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary (2nd ed.). London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Masson, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich (1988). Altyn-Depe. Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-934718-54-7. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-313-29497-6.

- ^ a b Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- ^ Leick, Gwendolyn (1998). A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology (1st ed.). London: Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-415-19811-0. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer (1st ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-090854-6.

- ^ Harris, Rivkah (February 1991). "Inanna-Ishtar as Paradox and a Coincidence of Opposites". History of Religions. 30 (3): 261–78. doi:10.1086/463228. S2CID 162322517.

- ^ "Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses – Anšar and Kišar (god and goddess)". Oracc. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Leeming, David (2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 122–124. ISBN 978-0-19-028888-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses – Marduk (god)". Oracc. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter W. (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. pp. 543–549. ISBN 978-0-8028-2491-2.

- ^ Bienkowski, Piotr; Millard, Alan (2000). Dictionary of the ancient Near East. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-8122-2115-2. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Reconstruction:Proto-Germanic/gudą". Wiktionary. 24 October 2020. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "áss". Wiktionary. 3 July 2022. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "ásynja". Wiktionary. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ a b Lindow, John (2002). Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983969-8. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d Warner, Marina (2003). World of Myths. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70204-2. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija; Dexter, Miriam Robbins (2001). The Living Goddesses (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 191–196. ISBN 978-0-520-22915-0.

- ^ Christensen, Lisbeth Bredholt; Hammer, Olav; Warburton, David (2014). The Handbook of Religions in Ancient Europe. Routledge. pp. 328–329. ISBN 978-1-317-54453-1. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Oosten, Jarich G. (2015). The War of the Gods (RLE Myth): The Social Code in Indo-European Mythology. Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-317-55584-1. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Horrell, Thad N. (2012). "Heathenry as a Postcolonial Movement". The Journal of Religion, Identity, and Politics. 1 (1): 1.

- ^ a b Martin, Thomas R. (2013). Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-300-16005-5. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gagarin, Michael (2009). Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Burkert, Walter (1985). Greek Religion (11th ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-36281-9. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ West, Martin Litchfield (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 166–173. ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9.

- ^ Breitenberger, Barbara (2005). Aphrodite and Eros: The Development of Greek Erotic Mythology. New York: Routledge. pp. 8–12. ISBN 978-0-415-96823-2. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Cyrino, Monica S. (2010). Aphrodite. New York: Routledge. pp. 59–52. ISBN 978-0-415-77523-6. Retrieved 22 January 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Puhvel, Jaan (1989). Comparative Mythology (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8018-3938-2.

- ^ Marcovich, Miroslav (1996). "From Ishtar to Aphrodite". Journal of Aesthetic Education. 39 (2): 43–59. doi:10.2307/3333191. JSTOR 3333191.

- ^ Flensted-Jensen, Pernille (2000). Further Studies in the Ancient Greek Polis. Stuttgart: Steiner. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-3-515-07607-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Pollard, John Ricard Thornhill; Adkins, A.W.H. (19 September 1998). "Greek religion". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ a b Campbell, Kenneth L. (2014). Western Civilization: A Global and Comparative Approach Volume I: To 1715. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45227-0. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Stoll, Heinrich Wilhelm (1852). Handbook of the religion and mythology of the Greeks. p. 3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Garland, Robert (1992). Introducing New Gods: The Politics of Athenian Religion. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-8014-2766-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Long, Charlotte R. (1987). The Twelve Gods of Greece and Rome. Brill Archive. pp. 232–243. ISBN 978-90-04-07716-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Woodard, Roger (2013). Myth, ritual, and the warrior in Roman and Indo-European antiquity (1st ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–26, 93–96, 194–196. ISBN 978-1-107-02240-9. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Ruiz, Angel (2013). Poetic Language and Religion in Greece and Rome. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1-4438-5565-5. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Mysliwiec, Karol; Lorton, David (2000). The Twilight of Ancient Egypt: First Millennium B.C.E. (1st ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-8014-8630-2.

- ^ Todd, Malcolm (2004). The Early Germans (2nd ed.). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-1-4051-3756-0. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Kristensen, f. (1960). The Meaning of Religion Lectures in the Phenomenology of Religion. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. p. 138. ISBN 978-94-017-6580-0. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Walsh, P.G. (1997). The Nature of the Gods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. xxvi. ISBN 978-0-19-162314-1. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Barfield, Raymond (2011). The Ancient Quarrel Between Philosophy and Poetry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-139-49709-1. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Roza, Greg (2007). Incan Mythology and Other Myths of the Andes (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 27–30. ISBN 978-1-4042-0739-4. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Littleton, C. Scott (2005). Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology: Vol. 6. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish Corporation. ISBN 978-0-7614-7565-1. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Kolata, Alan L. (2013). Ancient Inca. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-521-86900-3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Sherman, Josepha (2015). Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore. Routledge. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-317-45938-5. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Parker, Janet; Stanton, Julie (2006). Mythology: Myths, Legends and Fantasies. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik. p. 501. ISBN 978-1-77007-453-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 2243–2244. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Koschorke, Klaus; Ludwig, Frieder; Delgado, Mariano; Spliesgart, Roland (2007). A History of Christianity in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, 1450–1990: A Documentary Sourcebook. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. pp. 323–325. ISBN 978-0-8028-2889-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Kuznar, Lawrence A. (2001). Ethnoarchaeology of Andean South America: Contributions to Archaeological Method and Theory. Ann Arbor, MI: International Monographs in Prehistory. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-1-879621-29-9. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Fagan, Brian M.; Beck, Charlotte (2006). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-19-507618-9. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Insoll, Timothy (2011). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 563–567. ISBN 978-0-19-923244-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Issitt, Micah Lee; Main, Carlyn (2014). Hidden Religion: The Greatest Mysteries and Symbols of the World's Religious Beliefs: The Greatest Mysteries and Symbols of the World's Religious Beliefs. ABC-CLIO. pp. 373–375. ISBN 978-1-61069-478-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Faust, Katherine A.; Richter, Kim N. (2015). The Huasteca: Culture, History, and Interregional Exchange. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-0-8061-4957-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Williamson, Robert W. (2013). Religion and Social Organization in Central Polynesia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-62569-3. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Coulter, Charles Russel (2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-96390-3. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Emery, Gilles; Levering, Matthew (2011). The Oxford Handbook of the Trinity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955781-3. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b La Due, William J. (2003). Trinity Guide to the Trinity. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-56338-395-3. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ a b Badcock, Gary D. (1997). Light of Truth and Fire of Love: A Theology of the Holy Spirit. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8028-4288-6. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Olson, Roger E. (1999). The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition & Reform. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8308-1505-0. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Greggs, Tom (2009). Barth, Origen, and Universal Salvation: Restoring Particularity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-19-956048-6. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Larsen, Timothy; Treier, Daniel J. (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Evangelical Theology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-82750-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Aslanoff, Catherine (1995). The Incarnate God: The Feasts and the life of Jesus Christ. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-130-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Inbody, Tyron (2005). The Faith of the Christian Church: An Introduction to Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 205–232. ISBN 978-0-8028-4151-3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Zeki Saritoprak (2006). "Allah". In Oliver Leaman (ed.). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-4153-2639-1. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ a b Vincent J. Cornell (2005). "God: God in Islam". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 5 (2nd ed.). MacMillan Reference. p. 724.

- ^ "God". Islam: Empire of Faith. PBS. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Islam and Christianity", Encyclopedia of Christianity (2001): Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews also refer to God as Allāh.

- ^ Gardet, L. "Allah". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Online. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

- ^ a b Hammer, Juliane; Safi, Omid (2013). The Cambridge Companion to American Islam (1st ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-107-00241-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Yust, Karen Marie (2006). Nurturing Child and Adolescent Spirituality: Perspectives from the World's Religious Traditions. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4616-6590-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Piamenta, Moshe (1983). The Muslim Conception of God and Human Welfare: As Reflected in Everyday Arabic Speech. Brill Archive. pp. 16–17. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Terry, Michael (2013). Reader's Guide to Judaism. Routledge. pp. 287–288. ISBN 978-1-135-94150-5. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Kochan, Lionel (1990). Jews, Idols, and Messiahs: The Challenge from History. Oxford: B. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-15477-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Kaplan, Aryeh (1983). The Aryeh Kaplan Reader: The Gift He Left Behind : Collected Essays on Jewish Themes from the Noted Writer and Thinker (1st ed.). Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-89906-173-3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.