Hartcliffe

| Hartcliffe | |

|---|---|

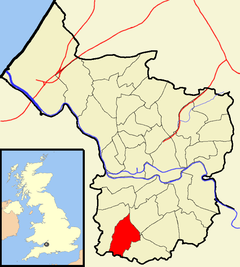

Boundaries of the former city council ward (1999-2016). | |

| Population | 11,474 (2011 ward)[1] |

| OS grid reference | ST584679 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BRISTOL |

| Postcode district | BS13 |

| Dialling code | 0117 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Avon |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Hartcliffe is an outer suburb of the city of Bristol, England, on the southern edge of the city at the foot of Dundry Hill. It is a post-World War II development consisting largely of council houses. It is one of the poorer areas of Bristol, with significant social problems exacerbated by the decline of industrial employment in the city.

Hartcliffe was also the name of an electoral ward for Bristol City Council from 1999 to 2016. The ward contained the areas of Hartcliffe and Headley Park as well as small portions of Withywood and Bishopsworth.[2] Since 2016, Hartcliffe has been in Hartcliffe and Withywood electoral ward.[3]

History

[edit]

In 1951, 696 acres (2.82 km2) of Bishopsworth parish were transferred from Somserset to Bristol,[4] and construction started in 1952 after the compulsory purchase of the farms on this land. A small shopping area was built at Symes Avenue, and the first church (St Andrew) opened in 1956.

Imperial Tobacco once had offices and a factory in Hartcliffe. Part of the site is now the Imperial Retail Park while the listed headquarters building has been converted into the Lakeshore flats.

Community facilities

[edit]Hartcliffe and Withywood Community Partnership (HWCP) was formed by local residents in 1998 to help support the regeneration and renewal of the area.

Schools within Hartcliffe include Fair Furlong Primary School, Hareclive Academy, and Bridge Learning Campus.

Hartcliffe Community Farm was opened in 1979 by Hartcliffe Community Council leader Doris Fiedor (1919–1995) who founded the community farm. It has over 30 acres (120,000 m2) of land based at the farmyard at the top of Lampton Avenue, Hartcliffe. A 250-year-old tithe barn was erected at the farm by YTS trainees but burned down in an arson attack. The farm remains open daily to the public and hosts regular visits by school parties.

Symes Avenue is the district shopping centre serving the outer estates of Hartcliffe and Withywood with a total population of around 20,000 people. In 2007, a Morrisons supermarket and a new library opened as part of a redevelopment project.

Economic and social deprivation

[edit]The estates have long been identified as suffering a multitude of different problems which characterise a socially excluded community.[5]

On 16 July 1992 there was a riot in Hartcliffe after two men who were riding a stolen and unmarked police motorbike were killed in a chase with an unmarked police car. The disturbance lasted for three days. Police were stoned and many shops in the Symes Avenue shopping centre were attacked and destroyed. Around the same time, Liberal Democrat leader Paddy Ashdown claimed that health indicators in the area were comparable to those of a Third World country.[6]

According to crime statistics between 2017–2018, The Groves in Hartcliffe is considered one of Bristol's ten most dangerous streets.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "Hartcliffe" (PDF). 2011 Census Ward Information Sheet. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ legislation.gov.uk – The City of Bristol (Electoral Changes) Order 1998. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ legislation.gov.uk – The Bristol (Electoral Changes) Order 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ The Somerset and Bristol (Alteraton of boundaries) Order, 1951

- ^ Ewles, Linda; Harris, Wendy; Roberts, Einir; Shepard, Mike (2001). "Community health development on a Bristol housing estate: A review of a local project ten years on". Health Education Journal. 66 (1): 59–72. doi:10.1177/001789690106000107. S2CID 72771424.

- ^ "No-Go Britain: Where, what, why". The Independent. 16 April 1994.

- ^ Turnnidge, Sarah; Goodier, Michael (10 November 2018). "These are Bristol's most dangerous streets". BristolLive. Retrieved 1 August 2022.