Turco-Egyptian Sudan

Turco-Egyptian Sudan السودان التركي-المصري (Arabic) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1820–1885 | |||||||||||||

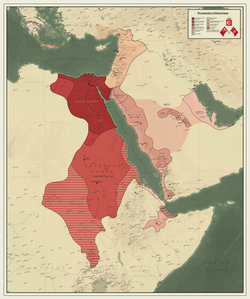

Map of Egypt with the Egyptian Sudan in the south | |||||||||||||

| Status | Administrative division of Eyalet of Egypt, Ottoman Empire (1820–1867) Administrative division of Khedivate of Egypt, Ottoman Empire (1867–1885) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Khartoum | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, English | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||

• 1820–1848 (first) | Muhammad Ali Pasha | ||||||||||||

• 1879–1885 (last) | Tewfik Pasha | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| 1820 | |||||||||||||

| 1885 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Egyptian pound | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| History of Sudan | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Before 1956 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Since 1955 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| By region | ||||||||||||||||||

| By topic | ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

Turco-Egyptian Sudan (Arabic: التركى المصرى السودان), also known as Turkiyya (Arabic: التركية, at-Turkiyyah) or Turkish Sudan, describes the rule of the Eyalet and later Khedivate of Egypt over what is now Sudan and South Sudan. It lasted from 1820, when Muhammad Ali Pasha started his conquest of Sudan, to the fall of Khartoum in 1885 to Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi.[1][2]

Background

[edit]After Muhammad Ali crushed the Mamluks in Egypt, a party of them escaped and fled south. In 1811 these Mamluks established a state at Dunqulah as a base for their slave trading.

In 1820 the Sultan of Sennar, Badi VII informed Muhammad Ali that he was unable to comply with the demand to expel the Mamluks. In response Muhammad Ali sent 4,000 troops to invade Sudan, clear it of Mamluks, and incorporate it into Egypt. His forces received the submission of the Kashif, dispersed the Dunqulah Mamluks, conquered Kurdufan, and accepted Sannar's surrender from Badi VII. However, the Arab Ja'alin tribes offered stiff resistance.[3]

The 'Turkiyyah'

[edit]'At-Turkiyyah' (Arabic: التركية) was the general Sudanese term for the period of Egyptian and Anglo-Egyptian rule, from the conquest in 1820 until the Mahdist takeover in the 1880s. Meaning both 'Turkish rule' and 'the period of Turkish rule', it designated rule by notionally Turkish-speaking elites or by those they appointed. At the top levels of the army and administration this usually meant Turkish-speaking Egyptians, but it also included Albanians, Greeks, Levantine Arabs and others with positions within the Egyptian state of Muhammad Ali and his descendants. The term also included Europeans such as Emin Pasha and Charles George Gordon, who were employed in the service of the Khedives of Egypt. The 'Turkish connection' was that the Khedives of Egypt were nominal vassals of the Ottoman Empire, so all acts were done, notionally, in the name of the Ottoman Sultan in Constantinople. The Egyptian elite may be described as 'notionally' Turkish speaking because while Ali's grandson Ismail Pasha, who took over power in Egypt, spoke Turkish and could not speak Arabic, Arabic rapidly became widely used in the army and administration in the following decades, until under the Khedive Ismail Arabic was made the official language of government, with Turkish being confined only to correspondence with the Sublime Porte.[4][5] The term al-turkiyyah alth-thaniya (Arabic: التركية الثانية) meaning 'second Turkiyyah' was used in Sudan to denote the period of Anglo-Egyptian rule (1899–1956).[6][7]

Egyptian rule

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

Under the new government established in 1821, Egyptian soldiers lived off the land and exacted exorbitant taxes from the population. They also destroyed many ancient Meroitic pyramids searching for hidden gold. Furthermore, slave trading increased, causing many of the inhabitants of the fertile Al Jazirah, heartland of Funj, to flee to escape the slave traders. Within a year of Muhammad Ali's victory, 30,000 Sudanese were conscripted and sent to Egypt for training and induction into the army. So many perished from disease and the unfamiliar climate that the survivors could only be used in garrisons in Sudan.

As Egyptian rule became more secure, the government became less harsh. Egypt saddled Sudan with a burdensome bureaucracy and expected the country to be self-supporting. Farmers and herders gradually returned to Al Jazirah. Muhammad Ali also won the allegiance of some tribal and religious leaders by granting them a tax exemption. Egyptian soldiers and Sudanese jahidiyah (conscripted soldiers), supplemented by mercenaries, manned garrisons in Khartoum, Kassala, and Al Ubayyid and at several smaller outposts.

The Shaiqiyah, Arabic speakers who had resisted Egyptian occupation, were defeated and allowed to serve the Egyptian rulers as tax collectors and irregular cavalry under their own shaykhs. The Egyptians divided Sudan into provinces, which they then subdivided into smaller administrative units that usually corresponded to tribal territories. In 1823, Khartoum had become the centre of the Egyptian domains in Sudan and had quickly grown into a large market town. By 1834, it had a population of 15,000 and was the residence of the Egyptian deputy.[8] In 1835 Khartoum became the seat of the Hakimadar (governor general). Many garrison towns also developed into administrative centers in their respective regions. At the local level, shaykhs and traditional tribal chieftains assumed administrative responsibilities.

In the 1850s, the Egyptians revised the legal system in both Egypt and Sudan, introducing a commercial code and a criminal code administered in secular courts. The change reduced the prestige of the qadis (Islamic judges) whose sharia courts were confined to dealing with matters of personal status. Even in this area, the courts lacked credibility in the eyes of Sudanese Muslims because they conducted hearings according to the Hanafi school of law rather than the stricter Maliki school traditional in the area.

The Egyptians also undertook a mosque-building program and staffed religious schools and courts with teachers and judges trained at Cairo's Al Azhar University. The government favored the Khatmiyyah, a traditional religious order, because its leaders preached cooperation with the regime. But Sudanese Muslims condemned the official orthodoxy as decadent because it had rejected many popular beliefs and practices.

Until its gradual suppression in the 1860s, the slave trade was the most profitable undertaking in Sudan and was the focus of Egyptian interests in the country. The government encouraged economic development through state monopolies that had exported slaves, ivory, and gum arabic. In some areas, tribal land, which had been held in common, became the private property of the sheikhs and was sometimes sold to buyers outside the tribe.

Muhammad Ali's immediate successors, Abbas I (1849–54) and Said (1854–63), lacked leadership qualities and paid little attention to Sudan, but the reign of Ismail I (1863–79) revitalized Egyptian interest in the country. In 1865 the Ottoman Empire ceded the Red Sea coast and its ports to Egypt. Two years later, the Ottoman Sultan formally recognized Ismail as Khedive of Egypt and Sudan, a title Muhammad Ali had previously used without Ottoman sanction. Egypt organized and garrisoned the new provinces of Upper Nile, Bahr al Ghazal, and Equatoria and, in 1874, conquered and annexed Darfur.

Ismail named Europeans to provincial governorships and appointed Sudanese to more responsible government positions. Under prodding from Britain, Ismail took steps to complete the elimination of the slave trade in the north of present-day Sudan. He also tried to build a new army on the European model that no longer would depend on slaves to provide manpower.

This modernization process caused unrest. Army units mutinied, and many Sudanese resented the quartering of troops among the civilian population and the use of Sudanese forced labor on public projects. Efforts to suppress the slave trade angered the urban merchant class and the Baqqara Arabs, who had grown prosperous by selling slaves.

Development

[edit]Khartoum was expanded from a military encampment to a town of over 500 brick-built houses by the first Egyptian Governor-General, Khurshid Pasha.[9]

New taxes imposed by the Defterdar Bey and his successor Uthman Bey the Circassian were so severe and fear of violent reprisals so acute that in many cultivated areas along the Nile, people simply abandoned their land and fled into the hills. His successors Mahu Bey Orfali and the first Governor-General, Ali Khurshid Pasha were more conciliatory, and Khurshid Bey agreed an amnesty for returning refugees who had fled to the Al-Atish border region with Ethiopia, as well as complete exemption from taxes for all shaykhs and religious leaders.[10]

Despite lack of early success in finding gold mines in Sudan, the Egyptians continued prospecting long after the initial conquest of the country. There was renewed interest in the Fazogli region in the 1830s, and Muhammad Ali sent European mineralogists there to investigate, eventually, despite being in his seventieth year, visiting the area himself in the winter of 1838–1839. Only a small amount of alluvial gold was ever found, and in the end Fazogli was developed not as a mining centre, but as an Egyptian penal colony.[11]

Sudanese slave soldiers

[edit]

In the 1830s, as Muhammad Ali's military ambitions drew his attentions elsewhere, Egyptian manpower in Sudan was reduced and 'Ali Kurshid Pasha, Governor General of the Sudan (1826–1838), had to increase the size of the locally recruited slave garrisons. He made periodic raids into the upper Blue Nile region and the Nuba Mountains, as well as down the White Nile, attacking the Dinka and Shilluk territories and bringing slaves back to Khartoum.[12]

Slave raiding was a demanding and not always profitable business however, in 1830 his assault on the Shilluk at Fashoda involved 2,000 soldiers but took only 200 slaves; in 1831–1832 an expedition of 6,000 attacked Jabal Taka in the Nuba Mountains. The assault was not successful, and Khurshid lost 1,500 men. Rustum Bey, Governor of Kordofan under Khurshid, had rather more success, conducting slaving expeditions in the west. In January 1830, he led an expedition which took 1,400 captives. He selected 1,000 young males from among them and sent them to Egypt. in 1832, a similar expedition by Rustum yielded another 1,500 captives, who were recruited for the army. Khurshid's successor as Governor-General, Ahmed Pasha, found a more economical way of recruiting slaves. Instead of raiding to fill the gaps in his black regiments, he imposed a new tax whereby each taxable individual was obliged to buy and hand over one or more slaves. Governor-General Mūsā Pasha Ḥamdī (1862–1865) combined the two practices, requiring shaykhs and chieftains to supply him with specified numbers of slaves, and personally leading raids to capture others when this proved insufficient. Under the reign of the Khedive Abbas I (1848–1854), each local shaykh or chieftain was required to supply the government with a specific number of men as part of their annual taxes. In 1859 his successor Muhammad Sa'id (1854–1863) ordered the formation of a personal bodyguard of black soldiers, and slaves continued to be taken mainly for the Sudanese regiments and for this bodyguard even after the official prohibition of the slave trade.[13]

In 1852, the Egyptian army in Sudan was 18,000 strong, and by 1865 it had increased to over 27,000. The bulk of the Egyptian occupation forces in Sudan were either slaves, or voluntarily recruited from within the country. The officers and non-commissioned officers were 'Turks' (meaning Turkish-speaking, whether Turkish, Albanian, Greek, Slavic or Arab) and Egyptians, although in later years some trusted Sudanese of long service were promoted to the rank of corporal and sergeant, and indeed, under Khurshid, to commissioned officer ranks.[14]

Occasionally, Sudanese slave troops were used outside Sudan. In 1835, Kurshid received orders to raise two black regiments for service in Arabia against the Wahhabi insurgents. In 1863, French Emperor Napoleon III asked Muhammad Sa'id to lend him a Sudanese regiment to fight in the humid, malarial climate of Veracruz in support of Mexican Emperor Maximilian I. In January 1863, 447 Sudanese troops sailed from Alexandria. They proved to be excellent fighters against the Mexican rebels, and endured the climate much better than Europeans.[15] An exceptional case of a Sudanese slave who ended up fighting outside his homeland was Michele Amatore, probably from the Nuba Mountains, who joined the Bersaglieri regiment of the Piedmontese army in 1848.[16][17]

Territorial expansion

[edit]The Egyptians gradually rounded off their domains. They advanced southwards along the White Nile and reached Fashoda in 1828. In the west the Egyptians reached the borders of Darfur. The Red Sea ports of Suakin and Massawa came under their control. In 1838, Mohammed Ali arrived in the Sudan. He fitted out special expeditions to search for gold along the White and the Blue Nile. In 1840, the regions of Kassala and Taka were added to the Egyptian domains.

In 1831 Khurshid Pasha led a 6,000-strong force east to attack the Hadendoa. He crossed the Atbarah River at Quz Rajab,[18] but the Hadendoa lured the Egyptians into a forest ambush, in which they lost all their cavalry. The infantry straggled back to Khartoum, first losing and then recovering their field artillery. In all the Egyptians lost 1,500 soldiers.[19] Nevertheless, the town of Gallabat submitted to Khurshid in 1832[20]

In 1837 Egyptian tax-collectors killed an Ethiopian priest in Sudan. This prompted a large Ethiopian force of some 20,000 to descend onto the Sudanese plain. The Egyptian garrison of 300 at al-Atish, east of El-Gadarif, was reinforced with 600 regular troops, 400 Berber irregulars and 200 Shayqiyya cavalry. The Egyptian commander was a civilian with no military experience, leading to the Ethiopians winning an easy victory before withdrawing.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Warburg, Gabriel R. (1991). "The Turco-Egyptian Sudan: A Recent Historiographical Controversy". Die Welt des Islams. 31 (2). Brill: 193–215. doi:10.2307/1570579. ISSN 0043-2539. JSTOR 1570579. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Introduction - 1 - Egypt and the Sudan - Gabriel R. Warburg". Taylor & Francis. 24 October 2018. doi:10.4324/9781315035055-1. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Beška, Emanuel, Muhammad Ali´s Conquest of Sudan (1820-1824). Asian and African Studies, 2019, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 30-56. url=https://www.academia.edu/39235604/MUHAMMAD_ALI_S_CONQUEST_OF_SUDAN_1820_1824_

- ^ Robert O. Collins, A History of Modern Sudan, Cambridge University Press, 2008 p.10

- ^ P. M. Holt, M. W. Daly, A History of the Sudan: From the Coming of Islam to the Present Day, Routledge 2014 p.36

- ^ Robert Collins, The British in the Sudan, 1898–1956: The Sweetness and the Sorrow, Springer, 1984 p.11

- ^ Gabriel Warburg, Islam, Sectarianism and Politics in Sudan Since the Mahdiyya, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2003 p.6

- ^ https://www.marxists.org/subject/arab-world/lutsky/ch07.htm accessed4/1/2017

- ^ Henry Dodwell, The Founder of Modern Egypt: A Study of Muhammad 'Ali, Cambridge University Press, Jun 9, 1931 p.53

- ^ John E. Flint, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 5, Cambridge University Press, 1977 p.31

- ^ John E. Flint, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 5, Cambridge University Press, 1977 p.31

- ^ Reda Mowafi, 'Slavery, Slave Trade and Abolition Attempts in Egypt and the Sudan 1820-1882, Scandinavian University Books 1981 p.21

- ^ Reda Mowafi, 'Slavery, Slave Trade and Abolition Attempts in Egypt and the Sudan 1820-1882, Scandinavian University Books 1981 pp.20-22

- ^ Reda Mowafi, 'Slavery, Slave Trade and Abolition Attempts in Egypt and the Sudan 1820-1882, Scandinavian University Books 1981 pp.21-22

- ^ Reda Mowafi, 'Slavery, Slave Trade and Abolition Attempts in Egypt and the Sudan 1820-1882, Scandinavian University Books 1981 p.22

- ^ "Bakhita Kwashe (Sr. Fortunata Quasce), Sudan / Egypt, Catholic". Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010. accessed 3/1/2017

- ^ Richard Leslie Hill, A Biographical Dictionary of the Sudan, Psychology Press, 1967 p.54

- ^ P. M. Holt, M. W. Daly, A History of the Sudan: From the Coming of Islam to the Present Day, Routledge 2014 p.46

- ^ Timothy J. Stapleton, A Military History of Africa ABC-CLIO, 2013 p.55

- ^ John E. Flint, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 5, Cambridge University Press, 1977 p.31

- ^ Timothy J. Stapleton, A Military History of Africa ABC-CLIO, 2013 p.56

Sources

[edit] This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. – Sudan

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. – Sudan- Beška, Emanuel, Muhammad Ali´s Conquest of Sudan (1820-1824). Asian and African Studies, 2019, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 30–56. url=https://www.academia.edu/39235604/MUHAMMAD_ALI_S_CONQUEST_OF_SUDAN_1820_1824_

- Dr. Mohamed H. Fadlalla, Short History of Sudan, iUniverse, 30 April 2004, ISBN 0-595-31425-2

- Dr. Mohamed Hassan Fadlalla, The Problem of Dar Fur, iUniverse, Inc. (21 July 2005), ISBN 978-0-595-36502-9

- Egyptian Royalty by Ahmed S. Kamel, Hassan Kamel Kelisli-Morali, Georges Soliman and Magda Malek.

- L'Egypte D'Antan... Egypt in Bygone Days Archived 22 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine by Max Karkegi.

- H.A. Ibrahim (1989). "The Sudan in the nineteenth century". In J. F. Ade Ajayi (ed.). Africa in the Nineteenth Century until the 1880s. General History of Africa. Vol. 6. UNESCO. pp. 356+. ISBN 0435948121.

- Hill, Richard (1959). Egypt in the Sudan, 1820-1881. Oxford University.