Horse symbolism

Horse symbolism is the study of the representation of the horse in mythology, religion, folklore, art, literature and psychoanalysis as a symbol, in its capacity to designate, to signify an abstract concept, beyond the physical reality of the quadruped animal. The horse has been associated with numerous roles and magical gifts throughout the ages and in all regions of the world where human populations have come into contact with it, making it the most symbolically charged animal, along with the snake.

Mythical and legendary horses often possess marvellous powers, such as the ability to speak, cross waters, travel to the Other World, the underworld and heaven, or carry an infinite number of people on their backs. They can be as good and Uranian as they are evil and Chtonian. Through the "centaur myth", expressed in most stories featuring a horse, the rider seeks to become one with his mount, combining animal instinct with human intelligence.

The horse's main function is as a vehicle, which is why it has become a shamanic and psychopomp animal, responsible for accompanying mankind on all its journeys. A loyal ally to the hero in epic tales, a tireless companion in cowboy adventures, the horse has become a symbol of war and political domination throughout history, a symbol of evil through its association with nightmares and demons, and a symbol of eroticism through the ambiguity of riding. The horse is familiar with the elements, especially water, from which the aquatic horse known in Celtic countries is derived. Air gave rise to the winged horse, known in Greece, China and Africa.

Literature, role-playing games and cinema have taken up these symbolic perceptions of the horse.

Origins and development of symbolic perception[edit]

The horse may have occupied a key symbolic position from the very beginning, since it is the most represented animal in prehistoric art,[1] favoured since the XXXV millennium BC, well before its domestication.[2] Representing the horse more than other equally (if not more) abundant animals was already a choice for prehistoric man. In the absence of concrete evidence to explain this choice, all interpretations remain possible, from the symbol of power[3] (according to the exhibition Le cheval, symbole de pouvoirs dans l'Europe préhistorique) to the shamanic animal (according to Jean Clottes' theory taken up by Marc-André Wagner). The horse also became a totemic ancestor, more or less deified.[4]

The symbolism of the horse is complex and multiple. It is not clearly defined, since authors attribute a wide variety of meanings to the animal, with no one meaning standing out above the others.[nb 1][5] In the stories associated with it, it has all kinds of roles and symbolisms, both beneficial and malefic:[6] a dynamic, impulsive mount, it is associated with all the points of the compass, with each of the four elements, with maternal figures (Carl Gustav Jung sees the horse as one of the archetypes of the mother, because it carries its rider[7] just as the mother carries her child, "In contrast, Sigmund Freud notes a case in which the horse is the image of the castrating father[8]), to the sun as well as the moon, to life as well as death, to the Chtonian as well as the Uranian world.[9] In its earliest symbolic perception, the horse was disquieting and chtonian, but later became associated with the sun as a result of its domestication.[10] It is most often a lunar animal linked to mother earth, water, sexuality, dreams, divination and the renewal of vegetation.[6] Gilbert Durand notes, in his Structures anthropologiques de l'imaginaire, that the horse "is linked to the great natural clocks", and that all stories, whether of solar horses or chtonian steeds, have in common "the fear of the passage of time".[11]

Its powers are beyond comprehension; it is therefore a marvel, and it's no wonder that man has so often made it sacred, from prehistoric times to the present day. Perhaps only one animal surpasses it in subtlety in the symbolic bestiary of all peoples: the serpent.

Ancient studies suggest that the origin of the marvellous "magical powers" attributed to the horse is Indian.[14][15] Henri Gougaud notes that "since time immemorial, strong, deep, unalterable bonds have attached man to his mount". The horse is both the animal most dear to man and the only one that man can respect as his equal, so much so that it is seen as a gift from the gods capable of lifting man out of his primate condition and into the celestial spheres.[16]

Domestication[edit]

The domestication of the horse, the feeling of freedom and the warlike power gained by cavaliers, means that this animal, a factor in major progress over the centuries, finds itself at the center of so many stories and is charged with multiple meanings. In myths, this domestication is often presented as an immediate and tacit understanding between rider and mount, sometimes with the help of the gods, as illustrated by Pegasus, Bucephalus and Grani. The historical reality, however, is one of a very long process.[17] In the cinema, this domestication is "an initiatory stage, a rite of passage between the wild state of childhood and the civilized state of adulthood".[18]

The centaur myth and the unconscious[edit]

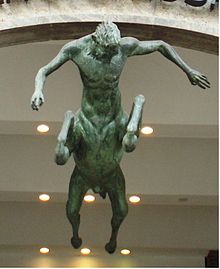

The "centaur myth" refers to "the perfect coupling between instinct and reason, between intelligence and brute force", as symbolized by the image of a human bust attached to a horse's body, rump and limbs.[19] The Dictionnaire des symboles asserts that all the rites, myths, poems and tales evoking the horse simply highlight this relationship between rider and mount, considered, in psychoanalytical terms, to represent that of the psychic and the mental: "if there is conflict between the two, the horse's race leads to madness and death, but if there is agreement, the race is triumphant".[6] For riders, it's a matter of controlling instinct (the animal part) with the mind (the human part). Carl Gustav Jung notes an intimate relationship between riders and mounts.[20] In Métamorphoses de l'âme et ses symboles (Metamorphoses of the Soul and its Symbols), he argues that "the horse seems to represent the idea of man, with the instinctual sphere subject to him [...] legends attribute to it characters that are psychologically linked to the unconscious of man: [they] are endowed with clairvoyance [...] they guide the lost [...] they have mantic faculties [... they also see] ghosts".[21] For him, the horse seems to metaphorize the libido, the psychic energy emanating from the unconscious,[22] and the animal part of the human being.[21] According to Marie-Louise von Franz, the horse represents animal, instinctual psychic energy, considered in its purest essence and often linked to the shadow, notably in Le Cycle du Graal.[23]

In his The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim explains the attraction of many little girls to the toy horses they comb or dress, and later the continuity of this attraction through riding and caring for horses, by the need to compensate for emotional desires: "by controlling an animal as large and powerful as the horse, the young girl has the feeling of controlling the animality or masculine part in her".[24] Freud, too, sees the horse as a "symbol of the unconscious psyche or the non-human psyche", the beast in man.[25]

According to Cadre Noir equestrian Patrice Franchet d'Espèrey, the myth of the centaur contains "everything related to the horse in the imagination", the rider's quest being to achieve perfect harmony with his mount, to "become one" with it.[26] Franchet d'Espèrey believes that this myth is recalled in all equestrian treatises from the 16th to the 20th century, reflecting man's mastery over nature.[27]

Symbolism evolution[edit]

Despite its disappearance from everyday life in favor of motorized vehicles, the horse remains "lurking in the deep collective subconscious". Olivier Domerc, former editor-in-chief of Culture Pub, argues that "unlike dogs and cats, the horse sells everything. Few animals have such a strong and universal image as a 'courier'".[28] Advertising specialists love the horse's unifying quality, which enables them to erase problems of race or religion in their advertising campaigns: the horse knows how to catch the eye when it's in the spotlight, thanks to its blend of power, grace, speed and strength, and is now seen as an alliance between dream and reality, virility and femininity.

Patrice Franchet d'Espèrey points out that, at the beginning of the 21st century, equestrianism has made the horse the embodiment of journeys into the great outdoors, of self-mastery, of mastery of others and of communication with nature.[29]

The vehicle[edit]

Through everything, hells, tombs,

Precipices, nothingness, lies,

And let us hear your hooves

On the ceiling of dreams

The first symbolic perception of the horse is that of a "vehicle" directed by man's will (volition) or guide, enabling it to be carried more rapidly from one point to another: "the horse is not an animal like any other, it is the mount, the vehicle, the vessel, and its destiny is inseparable from that of man".[6] Gilbert Durand speaks of "a violent vehicle, a steed whose strides surpass human possibilities".[30] In Métamorphoses de l'âme et ses symboles, Carl Gustav Jung speaks of the horse as "one of the most fundamental archetypes of mythologies, close to the symbolism of the tree of life". Like the tree of life, the horse connects all levels of the cosmos: the earthly plane where it runs, the subterranean plane with which it is familiar, and the celestial plane.[31] It is "dynamism and vehicle; it carries towards a goal like an instinct, but like instincts it is subject to panic".[32] In this sense, the horse motif is a fitting symbol for the Self, as it represents a meeting of antithetical and contradictory forces, conscious and unconscious, and the relationship linking them (just as an indefinable relationship unites rider and mount).[33] This perception derives directly from the physical qualities of mobility.[34] It transcends known space, since riding is a "transgression of psychic or metaphysical limits":[35] the horse enables us to cross the gates of hell as well as the boundaries of heaven, the disciple attains knowledge on his back, and many beliefs in metempsychosis relate adventures on horseback prior to reincarnation.[16] The horse can also play the role of captor.[36] Donald Woods Winnicott develops the importance of "carrying", which "enables liberation from physical and psychic constraints", and refers to sensations of early childhood.[37]

Shamanism[edit]

You have courage, but not intelligence, Töshtük .... If you do not follow my advice, you may perish, and see the world of the dead. ... Töshtük, have you ever sensed what I sense, or seen what I see?

The horse is the animal of shamanism and initiation rituals, an association it owes to its instinct, its clairvoyance, its psychoanalytical perception as the animal and intuitive part of man that illuminates reason, and its knowledge of the Other World.[38] This could be the horse's earliest and most ancient function, possibly dating back to prehistoric times, according to Jean Clottes' controversial theory that a number of cave paintings depict shamanic visions.[1]

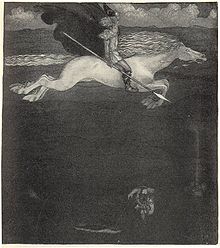

According to Mircea Eliade, in his trance, which aims to step outside himself and cross the limits of the known world, the shaman obtains the help of an animal-spirit and uses several objects, such as the horse-stick and the drum (usually stretched out in horsehide), which refer to the real animal. He then passes through other states of consciousness and can travel in a hellish direction or to heaven. In this sense, the horse, linked to the beating of the drum, enables the shaman to achieve a level break.[39][40] The horse is also the shaman's protector: the spirit-horse of Altai shamans is said to see thirty days into the future, watching over the lives of men and informing the deities.[41]

A shamanic background is perceptible in several ancient myths featuring a horse, notably that of Pegasus[42] (whose background is Asian), which symbolizes sublimated instinct and the wise man initiated through the ascent of Olympus,[43] and that of Sleipnir. The Kyrgyz legend of Tchal-Kouyrouk is more broadly linked to this, as the hero Töshtük must rely on the powers of his mount, which speaks and understands human language, to guide him through a subterranean universe to retrieve his soul.[44] The same applies to the epic of Niourgoun the Yakut, celestial warrior who rides a flying red steed endowed with speech.[45]

In Western medieval literature, however, the horse is presented as an anchor in the real world, as opposed to the Otherworld of fantasy and wonder. The knight who enters the realm of the fairies often abandons his mount, or has to make his way through dense vegetation at night.[46]

Rituals and possessions[edit]

A metamorphosis ritual from man to horse can be found in initiation rites involving possession. A man who surrenders to a higher spirit may be possessed by a demonic or positive entity, the "horse" being the channel through which they express themselves.[43] Voodoo in Haiti, Brazil and Africa, Egypt until the early 20th century, and Abyssinia are all involved. The possessed are straddled by spirits, then ruled by their will.[47] Followers of the Dionysus Mysteries in Asia Minor were symbolically straddled by their gods.[48] These possessions may also be found in ancient China, where new initiates were known as "young horses", while initiators were known as "horse traders",[43] like the propagators of Taoism and Amidism.[49] The organization of an initiation meeting is known as a "horse release".[43]

Hippomancy[edit]

As the intermediary between gods and men, responsible for carrying divine messages, the horse was given the role of oracle or diviner,[50] notably among the Persians and Celts of Antiquity. It can be a harbinger of triumph, war or even death:[43] according to the Greek Artemidorus of Daldis, dreaming of a horse during an illness heralds imminent death.

From shamanism to witchcraft[edit]

Several authors have noted the proximity between the horse-headed shamanic cane and the witch's broom in folklore.[51] According to Marc-André Wagner, the shamanic function of the horse has survived, if only symbolically, in Germanic folklore linked to witchcraft, with the sorceress using a staff as a mount. He also notes, thanks to a few etymological clues, that the generalization of the broom (after the 13th century) as a means of transport for witches probably stems from the previous figure, and originally from the shamanic horse, with which it retains as a link only its straw, reminiscent of the animal's tail.[52] The witch's broom is thus equivalent to the shamanic horse,[53] the animal that enables her to reach the Other World, seen here as that of evil powers.[54]

The nocturnal flight of the witch (or her double) is also reminiscent of that of the shaman, except that the witch is supposed to do evil by tormenting sleepers and going to the Sabbath. She could take on the form of a horse herself, transforming her victims so that she can ride them.[53] The Devil could also take horse form to carry her. Reports of witchcraft trials are replete with anecdotes mentioning the horse: a "sorcerer" from Ensisheim confessed on March 15, 1616 "that after attending a wedding of the Devil, he woke up lying in the carcass of a punctured horse".[55] In witchcraft tricks, the money given to witches by the Devil is often changed into horse manure. When members newly admitted to the practice of witchcraft wake up after the Sabbath, they have in their hand, instead of a cup, a horse's hoof; instead of a roast, a horse's head.[56]

Chtonian horse[edit]

The great victory represented by the domestication of the horse is not, in fact, a victory over the animal; it is a victory over the terror it has inspired in man since the dawn of time.

The horse has always aroused a sense of respect mixed with anguish and fear, a perception found in stories about horses of death, the underworld, nightmares, storms and other cursed hunts featuring carnivorous or evil animals. The chtonian horse belongs "to the fundamental structures of the imaginary".[57] Harpies are sometimes represented in the form of mares, one of which gives birth to Balius and Xanthus, Achilles' horses, one of which prophesies its master's death in the Iliad.[58]

Association with death[edit]

"Death horses or omens of death are very common,[nb 2] from the ancient Greek world to the Middle Ages, and with many interesting linguistic aspects".[59] They successively embody a messenger of death, a demon bringing death, and a guide to the afterlife, representing a psychic and spiritual reality.[60] The color black is strongly associated with them in Western traditions.[58] The death horse is associated with Demeter[61] and the chtonian god Hades.[62] Death horsemen include the Valkyries, the Schimmel Reiter and the Helhest.[62] Historically, the horse has more than once been called upon to deliver death by disembowelment, which may have marked the death-horse association, but is not the only explanation.[63] The horse is also one of the few animals to have been buried by man, as soon as it was domesticated.[64]

Passenger of the dead[edit]

The horse's role as "psychopomp", the animal responsible for carrying the souls of the deceased between earth and heaven, is attested to in many civilizations, notably by the Greeks and Etruscans, where it was part of mortuary statuary,[65] but also by the Germans and Central Asians.[66] On most ancient funerary stelae, it becomes an ideogram of death.[67] It would seem that the death-horse association stems from this role.[62] According to Franz Cumont, its origins go back to the practice of burying or burning dogs and horses with their masters, so that they could enjoy being together again.[68]

Norse mythology provides numerous examples of the horse becoming the intermediary between the mortal world and the underworld, making it the best animal to guide the dead on their final journey, thanks to its mobility.[34] The psychopomp horse of Greek mythology has a deep connection with water,[nb 3] seen as the boundary between the world of the living and the afterlife:[nb 4] the horse competes with the ferryman's boat (such as Charon) in this role,[69] just as it enables the shaman to complete his ecstatic journey.[70] This function has survived the centuries: in the Middle Ages, the stretcher was called "Saint Michael's horse".[58] This function is also found in China, where a horse-headed genie assists the judge of the underworld and transports souls. Similarly, the souls of male babies who died in infancy were represented on horseback by boatmen, and placed on the ancestral altar.[71]

The legend of Theodoric of Verona has it that the king was carried off on a "diabolical" black horse and subsequently became a ghost. Sometimes interpreted as evidence of the demonization of the horse in Germania, it would seem that this legend refers more to the belief that immortality could be attained on horseback.[72]

Funerary offering[edit]

The horse is buried, saddled and bridled, alongside its master, to fulfill this psychopomp role in the Altai region,[41] among the Avars, Lombards, Sarmatians, Huns,[73] Scythians, Germans[68] and many primitive Asian civilizations, where this burial is preceded by a ritual sacrifice. Greek mythology relates, in The Iliad, that Achilles sacrifices four horses on the funeral pyre where his friend Patroclus is consumed, so that they can guide him to the kingdom of Hades.[74] The Franks, who see the horse above all as a warrior animal, also sacrifice the king's horse to be buried alongside him.[75][76] These ritual sacrifices are sometimes preceded by a horse race.[77]

The pagan practice of burying a horse alive when a prestigious man dies is known to the Danes, and gives rise to the Helhest, or "horse of the dead", which is said to have been sacrificed and buried in a cemetery, then returned in a new form to guide dead humans.[78] The mere sight of a Helhest would be lethal.[79] Most of these rites were combated during successive Christianizations, and in Western Europe they disappeared in Carolingian times.[80]

Fantastic hunting[edit]

I saw beside me on a great black horse

A man with nothing but bones, by the look of him,

Holding out a hand to mount me on his rump

A trembling fear ran through my bones

The wild hunt, which pursues and terrorizes nocturnal travelers according to Christian folklore, is linked to the death horse, since it is made up of ghosts and the damned. It is often led by a black rider, such as Gallery (or Guillery), who chased a stag at mass time, and was condemned by a hermit to run after the inaccessible game in the sky every night, forever. This belief, shared by many countries, has its origins as much in the belief in ghosts as in the din of storms. The horse is present in both Arthur's and Odin's hunts.[58] According to Marc-André Wagner, this association in Germanic countries may be due to the banning and demonization of horsemeat, since they include the theme of a part of the hunt, often the animal's thigh. Other authors point to the clandestine practice of ritual equine sacrifice.[81]

Anthropophagy[edit]

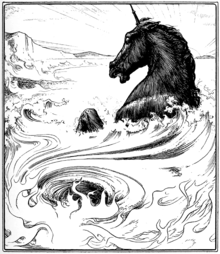

Several anthropophagous mares are mentioned in Greek mythology. Owned by a king who feeds them human flesh, they devour their master, whom Hercules has placed in their manger.[82] Glaucus' mares do the same to their master after Iolaos wins a chariot race. There are several possible interpretations: the consumption of magic herbs, the condemnation of the king to suffer the end he himself programmed (by feeding his mares human flesh), or Aphrodite's revenge for Glaucus' refusal to let his mares mate. The devouring of Glaucus would then be an erotic theme, a violent liberation of desire.[83] The horse Bucephalus is presented as an anthropophagus in an anonymous text from the 2nd century.[84] The presence of monstrous horses is not confined to antiquity: in fantasy literature, the Hrulgae are aggressive carnivorous quasi-horses with claws and fangs, from the Belgariade cycle.[85] They are also found in Celtic folklore in the form of water horses: Each Uisge (Scottish Gaelic) or Each Uisce (Irish Gaelic) offers himself as a mount to unwary passers-by, taking them into the water to devour them, leaving only the liver floating on the water. Similar stories of men being devoured by water horses can also be found in the Scottish legend of the Kelpies.[86]

Horsemen of the Apocalypse[edit]

One of the best-known evil representations of the horse is that of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, in the Bible. The horses' colors are white, fiery red, black and pale green. Their riders' mission is to exterminate through conquest, war, hunger and disease.[87] Numerous interpretations of this passage have been proposed, including that the horses represent the four elements, in order: air, fire, earth and water.[88]

Association to the Devil[edit]

According to Éric Baratay and Marc-André Wagner, during the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church passed off the horse as a diabolical animal, in order to combat the survival of pagan traditions (Celtic and Germanic in particular) that made it sacred.[89] The Devil thus appears on horseback, as a hippomorph, or with equine feet.[90] Although the horse is mentioned more often than the donkey in the Bible, the latter almost always has a positive symbolism, unlike the horse.[91]

Some Goethean demons ride horses, such as Eligos, Marquis Sabnock on his "pale horse",[92] Duke Berith on his "red horse",[93] and Alloces on his "huge horse".[94] Captain Orobas was originally described as a horse demon capable of taking on human form at will.[95] Carl Jung notes an analogy between the Devil as representative of the sexual instinct, and the horse: "This is why the Devil's sexual nature is also communicated to the horse: Loki takes this form in order to procreate".[96]

This association is no longer limited to Europe with the colonization of the Americas, since the black horse forced to build a church featured in many Quebec folklore stories is in fact the Devil in disguise.[97] The Mallet horse, another incarnation of the Devil as described by Claude Seignolle, lures its riders to death or serious injury.[98] The drac, a legendary creature linked to the Devil, dragons and water, takes the form of a black horse to tempt a marquis from the Basse Auvergne region to ride him, then nearly drowns him in a pond, according to a local legend.[99]

This Devil-horse association is particularly strong throughout ancient Germania, and hence in Alsace, where stories circulate of black horses appearing alone in the middle of the night. One of Strasbourg's animal ghosts is a three-legged horse believed to be the Devil. A rare book from 1675 tells of the Devil, disguised as an officer, riding the blacksmith's wife, whom he had transformed into a mare.[55]

The Christian Devil is not the only one associated with the horse, however, since Ahriman, the evil god of Zoroastrianism, takes this form in order to kidnap or kill his victims.[58]

Nightmare horses[edit]

The mare is etymologically close to the word nightmare in many languages: "mähre" means mare in German,[100] and also refers to a fabulous chtonian mare. The word is spelled nightmare in English, which also means "mare of the night", while in French quauquemaire means "witch". In Old Irish, mahrah means "death" and "epidemic". A long-held theory is that the black or pale horses and mares gave rise to the french word "cauchemar" and its English equivalent nightmare.[101] March Malaen, the demonic horse of Welsh folklore, is also cited as the origin of nightmare manifestations (suffocation, oppression, fear of being trampled, etc.).[102]

Although the origin of the word "nightmare" is different,[103] popular belief has taken hold of this association, notably through Henry Fuseli's The Nightmare painting, although the horse is a late addition not appearing on the author's sketches.[103] In its role as a supernatural mount with demonic powers, the nightmare horse carries demons and sometimes merges with them. His figure derives from the psychopomp and chtonian horse, and his familiarity with darkness and death, which made him part of the "mythology of the nightmare".[104] However, this perception has been lost over time, especially with the end of the horse's everyday use.[105]

A creature known in the Anglosphere as the Nightmare, translated as "nightmare mare", "infernal steed" or even "palefroi of the underworld", was popularized thanks to its inclusion in the bestiary of the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game, in the form of a large black horse with fiery manes, although its characteristics derive from older folklore.

Political and military dominance[edit]

From a political and military point of view, the symbolism of the horse is above all used to enhance the power of its rider. This function is clearly visible in the abundant equestrian statuary, where the horse highlights a warrior or a man of power, particularly in the quadriga of Saint Mark.[106] The horse is used to dominate both the environment and men on foot.[107] In many cultures, the ability to organize horse races is seen as an assertion of political power.[108]

War animal[edit]

The horse is "the quintessential war animal":[65] Georges Dumézil associated it solely with the second Indo-European function, but this assertion needs to be qualified in the light of more recent discoveries, since the horse also participates in the royal function and fertility cults.[109] The author also draws inspiration from the Romans, who unambiguously associated the horse with the warrior function, as opposed to donkeys and mules, which were agricultural animals. The Equus October ritual thus dedicated the horse to Mars.[110] Equiria, horse races dedicated to Mars, may also have had an agrarian function.[111] It is in Celtic epics that this warlike aspect of the horse is most emphasized, associated with the chestnut coat.[65] While the initiation of chivalry is closely linked to this perception of the animal, the symbolism of the horse as the "privileged mount of the spiritual quest" should not be overlooked.[112]

The image of the horse as an animal of military domination became so entrenched that in France, with the advent of the Third Republic, no head of state dared ride a horse. However, it remained a feature of the July 14th Bastille Day military parade.[113] When striking workers pushed back horsemen, it was a strong sign of the workers' domination of the army. Although repression by horsemen is a thing of the past in most countries, this symbolic image endures.[114]

Royal symbol[edit]

The link between the horse and royalty has existed in many civilizations, notably among the Persians.[115] Some myths, such as that of Hippodamia in ancient Greece, use the horse as a means of acceding to royal marriage.[109] An Irish enthronement rite involved sacrificing a white mare, boiling it and sharing its flesh at a banquet. The pretender to the throne would then bathe in the animal's broth and emerge invested with secret powers. Here, the sacrificial mare symbolizes the earth, and the king the sky.[116] King Mark's horse's ears, often equated with a shameful animal mark in the earliest interpretations, are more likely a mark of royalty legitimizing the sovereign's function in Celtic society.[117]

Western kings often commissioned their own equestrian statue or portrait: the horse's back acted as a throne, enhancing their qualities of goodness, majesty and sovereign power.[118] The representation of a horse with a raised foreleg is that of royal authority ready to strike down opponents.[119] The white horse is the most popular in this role, with Henri IV of France's famous white horse undoubtedly a factor: it "attracts the eye and focuses attention". What's more, the symbolism of the white coat is more charged than with horses of other colors.[120] During political upheavals, the destruction of depictions of kings on horseback was a sign of protest.[121]

Adventure companion[edit]

Give me a fast horse, a bandit of sackcloth and rope, a wonderful woman and vast spaces to gallop. I'll fill your eyes with so much dust and gunpowder smoke that you won't think of yourself or the world around.

In both literature and film, mounting a horse is often seen as the starting point for adventure. This is the case in the novels of Chrétien de Troyes:[122] Erec, for example, chooses a horse and a sword, "following a creative impulse that leads him towards his own realization", and thus begins his initiatory quest for power and purity.[123] Closely linked to this is the image of the knight-errant, seeking adventure and deeds as he travels the world on horseback.[124]

In most epics, the horse is the hero's faithful and devoted ally, assisting him whatever the dangers. Bayard, the fairy-horse given to Renaud de Montauban,[nb 5] remains his faithful protector and ally even when Renaud betrays him by handing him over to Charlemagne, who then orders him drowned.

In fairy tales, the horse is never the hero of the story, even when it gives the tale its name, as in the case of Le Petit Cheval bossu. Unlike other animals in fairy tales, which are merely "masks for human weaknesses", the horse's powers seem limitless, and his loyalty to his master is always unwavering.[125]

In Westerns, the horse is omnipresent, allowing the cowboy to dream during the long hours he spends in the saddle. The symbolism of the marvellous horse of mythology is largely reflected: the horse of the Wild West is often capable of galloping for hours on end without ever tiring, obeys only its master and even feels affection for him, and proves to be extraordinarily intelligent.[126] Henri Gouraud says that "a cowboy without his mount is nothing but a centaur broken in two, a soul separated from a body, a being without deep existence, too alone, too clumsy to give our unconscious the speech nourished by an age-old dream. The true western hero is the horse, cinema's noblest conquest.[16]

Fertility and sexuality[edit]

There are other accounts, notably in the Rig-Veda, where the animal is associated with strength, fertility, creative power and youth, in both the sexual and spiritual sense. Demeter's horse head refers to the mare's role as mother goddess.[116] Celtic mare-goddesses such as Epona, Rhiannon and Macha seem to have descended from a prehistoric mother-earth deity "with whom kings mated on fixed dates to ensure the people a new year of prosperity",[127] and Marc-André Wagner postulates the existence of "a great Celtic goddess, equestrian or partially hippomorphic, linked to the earth and dispensing sovereignty and prosperity".[128] However, this myth weakened over time.[127]

Fertility rituals[edit]

Most Chtonian figures were associated with fertility, including the horse, and more frequently the mare. From the first century to the fifth, numerous archaeological findings attest to the existence of equine sacrifices for this purpose.[129] They sometimes shared a cosmogonic role.[130] In the past, this sacrifice gave legitimacy to a king: for example, the Christian Håkon I of Norway had to comply with the pagan ritual by consuming the liver of a sacrificed horse in order to guarantee the prosperity of his people, and to be accepted by them.[131] According to Georges Dumézil, the centaur myth may stem from an Indo-European rite involving men dressed as horses as part of fertilizing festivals at the end of winter, which would also explain why centaurs are linked to primitive instincts and nature.[132] In the Ashvamedha, the sovereign mimes an act of fertilization with the still-warm sex of the sacrificed horse, and in the Irish enthronement rite, the pretender to the throne does the same with the mare. It's a sacred marriage in both cases, and the incarnation of divinity in the horse, a probable Indo-European archetype.[133]

The Roman ritual Equus October consists of such a ritual sacrifice to thank the god Mars for protecting the year's harvests.[134] As Georges Dumézil points out, the horse's tail was credited with fertilizing powers in Roman times, as was the ox's tail in Africa. As for its role as the spirit of wheat, it is common to German and French agrarian societies. In Assam, a white horse effigy is thrown into the river at the end of the harvest, after a dance in which it is bombarded with eggs.[135] This role as the spirit of wheat takes on its full meaning in autumn, when the harvest has been gathered, and the field dies until the spring rebirth. The horse, "companion of all quests", helps the seed to get through the winter safely.[16]

The meat of a horse sacrificed as part of these rituals was sometimes eaten, and supposed to transmit the animal's strengths.[34] The Völsa þáttr, where a couple of pagan farmers keep a horse's penis and regard it as a god, bears witness to these "ancient ritual practices",[136] and underlines the sacred nature of the horse.[137]

Sexual energy and eroticism[edit]

Paul Diel speaks of the horse as a symbol of "the impetuosity of desire",[138] and many texts, notably the Greek epics, tell of gods changing into horses to mate.[139] In the Finnish epic Kalevala, Lemminkäinen interrupts a gathering of young girls, mounted on his steed, and abducts Kylliki. For Henri Gougaud, the horse symbolizes "sexual energy released without constraint".[16] Carl Jung links the Devil in his role as lightning god ("the horse's foot") to the animal's sexual and fertilizing role: the storm fertilizes the earth, and the lightning takes on a phallic meaning, making the horse's foot "the dispenser of the fertilizing liquid", and the horse a priapic animal whose hoofprints "are idols that dispense blessing and abundance, found property and serve to establish boundaries". This symbolism is echoed in the lucky horseshoe.[96]

The horse is a phallic animal, if only because of the ambiguity of the word chevaucher, widely shared by several languages. This image stems from the proximity between the rider, who "has the beast between his legs" and moves with cadenced movements, and coitus, during which we experience the exhilaration, sweat and sensations of an equestrian ride.[140] The satyrs of Greek mythology, known for their lecherous side, were originally partly hippomorphic, as they had a tail, ears and horse feet.[141]

Some poets use the word "pouliche" to designate a feisty young woman.[142] According to Jean-Paul Clébert, the white horse plays an erotic role in myths about the abduction, kidnapping and rape of foreign women.[143] The Hippomanes, a floating structure found in the amniotic fluid of mares, has long been attributed with aphrodisiac virtues, although it possesses no particular properties.[144]

Pederasty and homosexuality[edit]

Bernard Sergent has noted the proximity between the horse and pederasty in ancient Greece. The driving of a chariot appears to be an integral part of the initiation of an Eraste to his Eromenos.[145] In medieval Scandinavia, the passive homosexual was referred to as a "mare", which was tantamount to an insult, while the active homosexual was valued in his role as stallion. The horse-skirt, a carnival mask often performed by male brotherhoods and known since the Middle Ages, may have been linked to initiations (or hazing) between pederasts.[146]

Rape[edit]

Like the satyr, the centaur is renowned for its insatiable sexual appetite, going so far as to kidnap women and rape them.[147] Because of its symbolic (eroticism, fear of being trampled and bitten[148]) and etymological proximity to the nightmare, the horse is considered an incubus animal in many countries,[149] i.e. a rapist of women. This perception is evident in Füssli's Le Cauchemar, where "the horse comes from the outside and forces the space inside". The mere presence of his head and neck between the curtains symbolizes rape, while his body remains outside, in the night.[150] Carl Jung recounts the case of a woman whose husband had brutally grabbed her from behind, and who often dreamed "that a furious horse was leaping on her, trampling her belly with its hind legs".[21]

According to some versions of Merlin's birth, the incubus who gave birth to him had horse's feet.[151]

Links with the stars and elements[edit]

The horse has the peculiarity of being associated with each of the three constituent elements (air, water and fire) and the stars (sun and moon), appearing as their avatar or friend. Unlike the other three elements, which correspond to the etymology of the horse as an animal in motion, the earth appears far removed from its symbolism.[152] The positive chtonian horse, capable of guiding its rider through subterranean and infernal regions, is especially present in Central Asia, notably through the myth of Tchal-Kouirouk.[6]

Gilbert Durand distinguishes several types of animal, such as the chtonian, the winged and the solar.[153] The horse appears "galloping like blood in the veins, springing from the bowels of the earth or the abysses of the sea". The bearer of life and death, it is linked to "destructive and triumphant fire" and "nourishing and asphyxiating water". Among "the horses of fire and light represented by the mystical quadriga",[154] Carl Jung cites a particular motif, that of the signs of the planets and constellations. He adds that "the horses also represent the four elements".[155]

Water[edit]

Of the four elements, water is the one most often associated with the horse,[156] whether the animal is assimilated to an aquatic creature, linked to fairy-like beings such as Japan's kappa, or mounted by water deities. He may be born of water himself, or cause it to gush forth as he passes. This association can be as much about the positive and fertilizing aspects of water as about its dangerous aspects.[157]

Origins of the water-horse association[edit]

However, the rising tide presses, pushes and gains speed .... The tide enters, as immense reptiles would, the sinuous channels that wind through the shores; it lengthens, often with the speed of a galloping horse, and grows, always pushing new branches before it.

For Marc-André Wagner, this association dates back to Indo-European prehistory.[158] For Ishida Eiichiro, its widespread use throughout Eurasia, from the Mediterranean to Japan, may date back to an ancient fertility cult and the first agricultural societies, where the water animal was initially the bull. The horse replaced the bull as its use expanded.[159] Marlene Baum traces the first water-horse association back to the Scandinavian peoples of the Baltic and North Seas, who also used kenning as "wave horse" to designate the longest Viking boats.[160] This proximity could be due to a "symbolic agreement between two moving bodies", the horse enabling man to cross the waves thanks to its strength and understanding of the elements.[161]

Legend aside, popular imagination frequently associates horses with waves breaking on the shore. Traditionally, the tide at Mont Saint-Michel is said to arrive "at the speed of a galloping horse",[162] although in reality the horse's gallop is five times faster.[163]

The water-revealing horse[edit]

The most common myth is that of the horse revealing the water, such as Pegasus bringing forth the Hippocrene spring, the dowsing horse of the god Baldr according to Scandinavian folklore, Charlemagne's white horse digging a spring to quench the thirst of soldiers on campaign, Bertrand Du Guesclin's mare discovering the waters of La Roche-Posay,[156] or Bayard, creator of numerous fountains bearing his name in the Massif Central. One possible explanation lies in a belief shared throughout Eurasia, according to which the horse perceives the path of underground waters and can reveal them with a stroke of its hoof.[164]

Virtues are sometimes associated with these waters born beneath the horse's hoof. The Hippocrene acquires the gift of changing whoever drinks from it into a poet, which symbolizes the image of a child drinking from the spring, an "awakening of impulsive and imaginative forces".[164] At Stoumont, the Bayard horse is said to have left his mark on a quartzite boulder. The stagnant water in the basin of this Pas-Bayard is reputed to cure eye diseases and warts.[165]

The water-born horse[edit]

One of the oldest sources of legends associating water and horses can be found in the Rig-Veda, which gives birth to the horse from the ocean.[166] In Greek mythology, the horse is the attribute of the Greek sea god Poseidon, who is said to have created it with his trident. Seahorses pull his chariot through the waves.[167] The Celtic epic by Giolla Deacar speaks of palfrey born of the waves and coming from the Sidh, capable of carrying six warriors underwater as well as in the air.[168]

According to Raymond Bloch, this association, taken up in the Roman realm by Neptune, is then found, in medieval times, in the character of the pixie, following a linguistic evolution in which Neptune becomes the sea monster Neptunus, then the Neitun of the Romance of Thebes, the Nuitun under the influence of the words "night" and "nuire", and finally the pixie.[169] The memory of mythological horses, which are generally white and emerge from the sea, is present in medieval times, albeit in a very faded form: this is the case in the Tydorel lai, where a mysterious knight emerges from his maritime kingdom on the back of a white mount.[170]

The association between the horse and the sea is very common in Celtic countries (in France, for example, it's found mainly on the Breton coast and in Poitou, where the sea is called Grand'jument), which suggests that in France at least, its origins are Celtic.[171] Water horses (Kelpie, Aughisky, Bäckahäst...), often seen as fairy-like, are still mentioned in the folklore of many Western European countries. They share a strong affinity with the liquid element, as well as an irresistible beauty. Some are reputed to be extremely dangerous, seducing humans into riding them, then drowning or even devouring them. Their most common form is that of a beautiful black, white or dapple-gray horse that looks lost and stands at the water's edge, quietly grazing.[172] In Brittany, according to Pierre Dubois, all fabulous horses "reign over the sea" and three mares, aspects of the waves, possess the power to regulate the tides, calm the swell and the waves. Another leads the fish.[173] This symbolic association continues into modern times, as evidenced by films such as White Mane (Crin-Blanc) and Into the West (Le Cheval venu de la mer).

Horse sacrifice in the water[edit]

Horse sacrifice in water seems to have been practiced by many Indo-European peoples. The Persians performed this type of sacrifice in honor of the goddess Anahita, and the Russians drowned a stolen horse in the river Oka, as a seasonal offering to the "Great Father", the water genie.[nb 6][166] In ancient Greece, the purpose of the sacrifice was to win Poseidon's good graces before a sea expedition. According to Pausanias,[156] the inhabitants of Argolida sacrificed harnessed horses to the god, hurling them into the Dine river. In the Iliad, the Trojans sacrifice horses to the river Scamandre, seen as a divinity.[157]

The horse and the rain[edit]

The rain horse is seen as a fertility demon with a positive role.[174] Particularly in Africa, it assists deities. This is the case among the Ewes, where the mount of the rain god is seen as a shooting star. The Kwore, Bambara initiates, know a ritual for calling down rain, in which they ride a wooden horse symbolizing the winged mounts of their genies fighting against those who would prevent regenerative water from falling from the sky.[175]

In ancient Nordic religion, valkyries ride cloud horses whose manes bring dew to the valleys and hail to the forests.[176] In Lower Austria, the appearance of a giant on a white horse heralds the arrival of rain.[177]

Air[edit]

Horses of the wind[edit]

When God wanted to create the horse, he said to the south wind: "I want to bring a creature out of you, condense yourself" - and the wind condensed. Then came the angel Gabriel; he took a handful of this matter and presented it to God, who formed a horse out of it ... crying out: I called you horse, I created you Arab ... you will fly without wings

An archaic conception gives the wind hippomorphic traits,[178] and the alliance of horse and wind is often born of a common quality: speed. Carl Jung speaks of the wind's speed in the sense of intensity, "i.e. the tertium comparationis is still the symbol of libido. ... the wind a wild and lustful chaser of girls". He adds that centaurs are also wind gods.[96]

The winds are symbolized by four horses in Arab countries,[10] where it is said that Allah created the animal from this element.[nb 7] In India, the god of the winds, Vâyu, rides an antelope "as swift as the wind". In Greece, Aeolus was originally perceived as a horse,[178] and Boreas became a stallion in order to sire twelve foals as light as the wind with the mares of Erichthonios,[179][180] illustrating the epic mythological image of the wind fertilizing mares.[178]

A Tibetan belief taken up by Buddhism makes the wind horse an allegory of the human soul. Several antecedents can be traced. There has long been confusion between klung rta (river horse) and rlung rta (wind horse). "River horse" may have been the original concept, but the drift towards "wind horse" was reinforced by the association of the "ideal horse" (rta chogs) with speed and wind.[181]

Winged horses[edit]

As its name suggests, the winged horse has a pair of wings, generally feathered and inspired by those of birds, which enable it to fly through the air. Its earliest representations date back to the proto-Hittite period in the 19th century BC. It's possible that this myth later spread to the Assyrians, then to Asia Minor and Greece.[182] It can be found in regions as varied as China, Italy, Africa and even North America after its colonization by Europeans. It combines the usual symbolism of the horse with that of the bird, lightness and elevation. The winged horse is associated with spiritual elevation and victory over evil. The origin of the iconography and traditions that mention it is probably the ecstasy of the shaman who ascends to heaven on a winged creature, usually a bird. In all shamanic practices, the man who undertakes a spiritual journey is assisted by an "animal who has not forgotten how to acquire wings", failing which he cannot ascend. Like the Bambara's winged horse,[183] Pegasus is linked to notions of imagination, speed and immortality.[164]

Solar and Uranian horse[edit]

The association of the horse with the sun is known as far back as the Bronze Age:[184] it would seem that several peoples imagined and then represented the sun on a chariot to signify its movement.[10] According to Ernest Jones, the addition of the horse in front of this chariot may also have stemmed from man's early perception of the horse as a "shiny" animal: the Indo-European linguistic root for shine, MAR, is thought to have given rise to the English word "mare".[185] Most mythological accounts testify to an evolution in this association. Initially assimilated to a horse, often white, the sun is anthropomorphized to become a divinity of which the horse is an attribute.[186] The solar horse is the animal of phallic worship, fertility and reproduction.[185] In China, the horse is typically yang.[49]

Venceslas Kruta explains many artistic representations of horses from the Hallstatt period as being linked to a solar divinity.[184] Several authors even speculate that the earliest Celtic peoples knew of a divine solar horse or a fast-running sidereal equestrian deity, and that the horse was a symbol of the solar god, or at least of Eochaid Ollathair in his role as master of the heavens.[69][187]

The oldest attestation of the solar horse is found in the Ashvamedha sacrificial ritual in India, which includes a hymn from the Rig-Veda, saying that the gods "fashioned the horse from the substance of the sun".[184] The sun also appears in the form of a horse or a bird.[188] Indra's steeds have "eyes as bright as the sun". They harness themselves to their golden-yoked chariot,[189] their speed beyond thought.[190] The name of the Indian horse, asha, is closely linked to the penetrating light that embodies dharma and knowledge. The ashvins, divine horse-headed twins born of these animals, are linked to the cycle of day and night. Ratnasambhava, symbol of the sun, is represented on horseback.[10]

Among the ancient Scandinavians, this association appears on petroglyphs and numerous objects, the best known being the Trundholm Sun Chariot.[90] Among the Germanic peoples, the Skinfaxi and Árvak & Alsvid myths refer to a cosmic mount whose mane creates the day, and to a horse-drawn solar chariot,[191] but there are few relevant links to any equine solar cults.[115] The peoples of the Urals and Altai associate the earth with the ox and the sky with the solar male horse.[192]

In Greek mythology, Apollo replaces Helios and his chariot harnessed to the sun's horses,[186] but retains the horse as an attribute.[10] Roman mythology popularized the steeds of Helios' chariot by naming them and recounting the myth of Phaethon.[191] Solar cults and races in honor of this star bear witness to this association in Antiquity, both among the Romans through chariot races, and among the Persians at Salento,[193] as well as among the Greeks in Laconia and Rhodes.[115]

A solar chariot is attested to in the Bible (Second Book of Kings, II), harnessed to horses of fire, it carries Elijah into the sky. Vertical and aerial, the horses mark a break between the celestial and terrestrial worlds.[193] The Hortus Deliciarum, a medieval Christian encyclopedia, features a miniature of a solar chariot pulled by horses, probably a reworking of an ancient theme.[10]

Thunder and lightning[edit]

Gilbert Durand notes that the animal is associated with "dread of the passage of time symbolized by change and noise", most often in connection with aquatic constellations, thunder and the underworld.[194] Thunder horses" are characterized by their noisy gallop, a sound "isomorphic to the leonine roar".[195] Carl Jung also notes this analogy between the horse and lightning, and cites the case of a hysterical woman terrorized by thunderstorms, who saw a huge black horse fly up to the sky every time lightning struck. Mythology also knows of lightning-horse associations, notably with the Hindu god Yama. Finally, the horse's thigh was reputed to deflect lightning "according to the principle similia similibus".[96]

The importance of appearance[edit]

The horse's appearance also has symbolic significance, especially when it comes to coat color. Slavic and Germanic peoples may have used horses with mullet stripes and roan coats as totemic signs.[196] Numerous Icelandic documents in Old Norse mention horses with "Faxi" in their name, meaning "mane". This could be a distinctive mark. The white and black horses are the best known.

White[edit]

Like Pegasus, the positive animal of the celestial spheres, the white horse is most often a symbol of majesty and spiritual quest: Christ and his armies are sometimes depicted on its back, and the animal carries gods, heroes, saints and all kinds of prophets, such as Buddha. Kalki, the future avatar of Vishnu, is prophesied to take a white horse named Devadatta as his mount to fight the evil that plagues the world.[197] Svetovit, the powerful Slavic god of the Rugians, owns a sacred white horse.[198] Henri Dontenville reports a Jura belief in a white lady accompanied by greyhounds and white horses, playing harmonious, uplifting music with her horn.[199]

However, cursed horses of a cold, empty, pale white color, "lunar",[200] "nocturnal, livid like mists, ghosts, suars",[201] are known from folklore, such as the blanque mare and the Schimmel Reiter. Their whiteness has an opposite meaning to that of Uranian white horses: they evoke mourning, just as the white mount of one of the horsemen in the Apocalypse heralds death.[58] It's an inversion of the usual symbolism of the color white, a "deceptive appearance" and "gender confusion"[202] that has become an archetypal horse of death.[87] In England and Germany, meeting a white horse is a sign of bad omen or impending death.[203]

Black[edit]

Ah! My servants, my young servants!

Harness the grey oxen

And the black horses,

And let's go in search of my young years

In Western Europe, like most animals of this color (cats, ravens, etc.), the black horse suffered a symbolic decline, probably due to the influence of Christianity and the Bible.[204] It is now most often associated with the Devil, the Chtonian underworld and nightmares, but in Russia, it symbolizes vivacity and spirited youth, and is found harnessed to the bride and groom's chariot.[116]

In Breton legend, Morvac'h, who can run on the waves, is not described as evil, although storytellers say he exhales flames through his nostrils when galloping. The black horse is also a magical mount capable of speech in a tale from the More Celtic Fairy Tales,[205] and a young man who has learned to metamorphose in a Russian folk tale by Alexander Nikolayevich Afanasyev.[206]

In British folklore, the leprechaun Puck sometimes takes on the appearance of the black horse to frighten people.[207] In an Irish tale, Morty Sullivan rides a black horse that is in fact Phooka (Puck) in disguise, and knocks him down.[208]

The black knight is well known to folk traditions and writers alike.[209] In the Arthurian legend, Perceval defeats a black knight and takes his mount with him,[210] an episode with a possible alchemical symbolism linked to the animal's color.[211]

Recent films and literature, such as the saga of The Black Stallion, have given the black horse a new image, that of a wild, spirited animal that can only be ridden by a single person, with whom it shares a bond of trust close to the totemic kinship of medieval legends.[204]

Symbolic links[edit]

The horse has close links with other animals and mythical creatures, both according to myth and historical findings.

Deer[edit]

Marc-André Wagner notes a symbolic proximity between horses and cervids, no doubt linked to the domestication of reindeer, which served as mounts in the Nordic Eurasian steppes before the horse.[212] One piece of evidence lies in the exhumation of Scythian horses wearing reindeer antler masks, another in Kazakh and Siberian drawings blending equine features with those of deer.[213] Ancient Germanic and Celtic tombs have revealed deer and horses buried in ritual fashion, presumably to help accompany a warrior into the afterlife. It would seem that deer preceded horses in their role as mounts and carriage animals,[214] which also implies the loss of the psychopomp role initially attributed to them in favor of the horse.[215]

Elves[edit]

As Anne Martineau points out, "there are very close links between goblins and horses. So close, in fact, that in both medieval chansons de geste and more modern folklore, when the goblin takes animal form, it almost always adopts the former. In addition to the aforementioned link to the liquid element, the reason for this seems to be that the horse, an animal familiar to humans, is also the most appropriate for travelling to fairytale worlds and playing the elf's characteristic tricks, such as throwing a rider into a pool of mud, a river or a fountain. In medieval literature, Malabron (chanson de Gaufrey) and Zéphir (Perceforest) change into horses. Paul Sébillot reports popular beliefs about several horse sprites: the Bayard in Normandy, the Mourioche in Upper Brittany, Maître Jean, the Bugul Noz and the white mare of Bruz. In the Anglo-Saxon islands, Puck (or the Phooka) takes this form.[216]

Jean-Michel Doulet's study of changelins states that "at the water's edge, the silhouettes of goblin and horse tend to merge and merge into a single figure whose role is to lead astray, frighten and precipitate those who ride them into some pond or river".[217] Elficologist Pierre Dubois cites numerous household elves, one of whose roles is to look after the stables, and other, wilder ones, who visit the same places at night, leaving visible traces of their passage, for example by braiding the horses' manes, a trick known as fairy -lock.[218] Marc-André Wagner notes the Kobold, a Germanic household goblin seen as "he who watches over and administers the Kobe, the hut, the hearth, and by extension the house". As Kobe can also mean "stable", the Kobold would be the "guardian of horses", located in "the intermediate space between human civilization, the wild element and the supernatural world".[219]

Snakes and dragons[edit]

The Dictionnaire des Symbols identifies a number of links between snakes, dragons and horses. All are linked first and foremost to springs and rivers, such as the dragon-horse. Horses and dragons are often interchangeable in China, both associated with the quest for knowledge and immortality. They are opposed in the West, in the duel of the knight against the dragon, the horse symbolizing victorious good, and the dragon the beast to be destroyed, as illustrated by the legend of Saint George.[48]

One of Western Europe's best-known fabulous horses, Bayard, is a fairy-horse born of a dragon and a snake on a volcanic island, as well as an animal linked to earth and fire, embodying telluric energy and vigor.[220] It could himself be a metamorphosed dragon.[221]

Notes[edit]

- ^ For example, the fox symbolizes cunning, the rabbit fertility, the lion and the eagle royalty, but no meaning seems to be universally attached to the horse.

- ^ In hippomancy, dreaming of a horse is most often an omen of death.

- ^ See chapter on water below.

- ^ The River Styx separates the world of the living from that of the dead, and the Celtic Otherworld is usually reached by crossing water, for example.

- ^ By the enchanter Maugis, the fairy Oriande or King Charlemagne, depending on the version.

- ^ See the chapter on these rites earlier in the article.

- ^ This legend has many variants, the wind sometimes being from the south, sometimes from the four cardinal points, other times the sirocco...

References[edit]

- ^ a b Wagner 2005, p. 49.

- ^ (fr) Patrice Brun, "Un animal sauvage privilégié depuis le XXXVe millénaire avant J.-C", in Le cheval, symbole de pouvoirs dans l'Europe préhistorique, Musée départemental de préhistoire d'Ile-de-France, 2001, 104 p. (ISBN 978-2-913853-02-7), Exhibition from March 31 to November 12, 2001, Nemours.

- ^ Pigeaud 2001.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 182.

- ^ Cirlot 2002, p. 152.

- ^ a b c d e Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 223.

- ^ Quoted in Franchet d'Espèrey 2007, p. 156.

- ^ Ritzen, Quentin (1972). La scolastique freudienne. Expérience et psychologie (in French). Fayard. p. 122..

- ^ Nel 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 230.

- ^ Durand 1985, p. 72.

- ^ Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 231

- ^ Quoted in Bridier 2002, p. 75

- ^ Hayez, M. (1845). Bulletins de l'Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique (in French). Vol. 12. p. 175..

- ^ (fr) Hayez, M. (1845). Bulletins de l'Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique (in French). Vol. 12. p. 175..

- ^ a b c d e Gougaud 1973.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 72.

- ^ (fr) "Propositions de pistes pédagogiques " Le cheval venu de la mer " de Mike Newell" (PDF). Stage École et cinéma. October 2005. Retrieved 24 May 2011..

- ^ (fr) Jean Lacroix, "Le mythe du centaure aux xve et xvie siècle en Italie", in Mythe et création, Université de Lille III, Presses Univ. Septentrion, 1994 (ISBN 978-2-86531-061-6).

- ^ Jung 1993, p. 457.

- ^ a b c Jung 1993, p. 461.

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung, Métamorphoses et symboles de la libido, Éditions Montaigne, 1927, p. 266.

- ^ Emma Jung, et Marie-Louise von Franz, La légende du Graal, Paris, Albin Michel, 1988, p. 214-215.

- ^ Bruno Bettelheim (1999). Psychanalyse des contes de fées (in French). Pocket. pp. 90–91. ISBN 9782266095785..

- ^ Ángel Garma (1954). La psychanalyse des rêves (in French). Translated by Madeleine et Willy Baranger. Bibliothèque de psychanalyse et de psychologie clinique, Presses universitaires de France. pp. 240–252..

- ^ Franchet d'Espèrey 2007, pp. 154–158.

- ^ Franchet d'Espèrey 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Olivier Domerc quoted in Bastides-Coste 2004.

- ^ Franchet d'Espèrey 2007, p. 212.

- ^ Durand 1985, p. 80.

- ^ Jung 1993, pp. 460–462.

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung (1987). L'Homme à la découverte de son âme. Hors collection. Paris: Albin Michel. p. 269. ISBN 978-2226028211..

- ^ (fr) Carl Gustav Jung, "Aïon: Études sur la phénoménologie du Soi", in La réalité de l'âme, t. 2: Manifestations de l'inconscient, Paris, Le Livre de poche, 2007 (ISBN 978-2-253-13258-5), p. 680.

- ^ a b c Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; Raudvere, Catharina (2007). Old Norse religion in long-term perspectives: origins, changes, and interactions: an international conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3–7, 2004. Vägar till Midgård. Vol. 8. Nordic Academic Press. p. 130-134. ISBN 978-91-89116-81-8

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 139.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 76.

- ^ Donald Winnicott, quoted in Franchet d'Espèrey 2007, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Mircea Eliade (1978). Le chamanisme et les techniques archaïques de l'extase. Bibliothèque scientifique, Payot. p. 303 ; 366..

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 142.

- ^ a b Harva, Uno (1959). Les représentations religieuses des peuples altaïques (in French). Translated by Jean-Louis Perret. Paris: Gallimard. p. 112; 212..

- ^ See the chapter on spirituality in the ancient myth of Pegasus.

- ^ a b c d e Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 225.

- ^ (fr) Boratav, Pertev (1965). Aventures merveilleuses sous terre et ailleurs de Er-Töshtük le géant des steppes: traduit du kirghiz par Pertev Boratav (in French). Gallimard/Unesco. ISBN 2-07-071647-3 quoted by Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 223.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 126.

- ^ Collectif 1992, p. 212.

- ^ (fr) Michel Leiris, L'Afrique fantôme, Gallimard, 1934, p. 337.

- ^ a b Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 224.

- ^ a b Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 232.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 95.

- ^ Michel Praneuf, Bestiaire ethno-linguistique des peuples d'Europe, L'Harmattan, 2001, ISBN 9782747524261, p. 138.

- ^ Wagner 2005, pp. 50–52.

- ^ a b Bridier 2002, p. 80.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 144.

- ^ a b (fr) Notariat de M. Halm, Registre des maléfices d'Ensisheim de 1551-1632, quoted in Fédération des sociétés d'histoire et d'archéologie d'Alsace (1851). Revue d'Alsace (in French). Vol. 111. Fédération des sociétés d'histoire et d'archéologie d'Alsace. p. 554..

- ^ (fr) Fédération des sociétés d'histoire et d'archéologie d'Alsace (1851). Revue d'Alsace (in French). Vol. 111. Fédération des sociétés d'histoire et d'archéologie d'Alsace. p. 554..

- ^ (fr) Herzfeld, Claude (2008). Octave Mirbeau: aspects de la vie et de l'œuvre (in French). Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 252. ISBN 9782296053342..

- ^ a b c d e f Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 226.

- ^ (fr) Couret, Alain; Ogé, Frédéric; Audiot, Annick (1989). Homme, animal, société (in French). Presses de l'Institut d'études politiques de Toulouse. p. 181..

- ^ (de) Ludolf Malten, "Das pferd im Tautengloben", in Jahrbuch des Kaiderlich deutschen Archäologischen instituts, vol. XXIX, 1914, p. 179-255.

- ^ Henri Jeanmaire (1978). Dionysos: histoire du culte de Bacchus : l'orgiasme dans l'Antiquité et les temps modernes, origine du théâtre en Grèce, orphisme et mystique dionysiaque, évolution du dionysisme après Alexandre. Bibliothèque historique (in French). Payot. p. 284..

- ^ a b c Wagner 2006, p. 124.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 179–181.

- ^ a b c Wagner 2006, p. 96.

- ^ Wagner 2005, pp. 146–148.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 125.

- ^ a b Wagner 2005, p. 98.

- ^ a b T. F. O' Rahilly, The traveller of the Heavens, quoted by Milin, Gaël (1991). Le roi Marc aux oreilles de cheval. Publications romanes et françaises (in French). Vol. 197. Librairie Droz. p. 111. ISBN 9782600028868..

- ^ Marina Milićević Bradač. "Greek mythological horses and the world's boundary". HR 10000 Zagreb Department of Archaeology; Faculty of Philosophy..

- ^ Tournier 1991, p. 93.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 172–174.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 111.

- ^ Delebecque 1951, p. 241.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Michel Rouche (1996). Clovis (in French). Éditions Fayard. p. 198. ISBN 2-213-59632-8..

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Barton Gummere, Francis (1970). Founders of England. McGrath Pub. Co. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-8434-0107-3

- ^ Laurent Jean Baptiste Bérenger-Féraud (1896). Superstitions et survivances: étudiées au point de vue de leur origine et de leurs transformations (in French). Vol. 1. E. Leroux. p. 379..

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 136.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 475.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 36.

- ^ "La Belgariade". Retrieved 17 May 2011..

- ^ James Mackillop, Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, Oxford University Press, 1998, 2004

- ^ a b Pierre Sauzeau et André Sauzeau (1995). Les chevaux colorés de l'« apocalypse. Vol. 212. Revue de l'histoire des religions, université Montpellier III. pp. 259–298..

- ^ Girard, Marc (1991). Les symboles dans la Bible: essai de théologie biblique enracinée dans l'expérience humaine universelle. Recherches (in French). Les Éditions Fides. p. 858. ISBN 9782890070219..

- ^ Éric Baratay (2003). Et l'homme créa l'animal: histoire d'une condition. Sciences humaines (in French). Odile Jacob. p. 322. ISBN 9782738112477..

- ^ a b Wagner 2005, p. 724.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 454.

- ^ Crowley 1995, p. 50.

- ^ Crowley 1995, p. 40.

- ^ Jacques-Albin-Simon Collin de Plancy (1993). Dictionnaire infernal (in French). Slatkine. p. 22. ISBN 9782051012775..

- ^ Crowley 1995, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Jung 1993, p. 463.

- ^ Dionne & Beauchemin 1984, p. 328.

- ^ Édouard Brasey (2008). La petite encyclopédie du merveilleux (in French). Paris: Le pré aux clercs. p. 254-255. ISBN 978-2-84228-321-6.

- ^ Bessière 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Bridier 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Haggerty Krappe, Alexander (1938). La genèse des mythes. Bibliothèque scientifique (in French). Payot. p. 229..

- ^ (fr) Tristan Mandon. "BESTIAIRE Deuxième section : Du Cheval au Cygne..." (PDF). Les Origines de l'Arbre de Mai dans la cosmogonie runique des Atlantes boréens. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ a b Bridier 2002, p. 74.

- ^ Bridier 2002, p. 76.

- ^ Bridier 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Sevestre & Rosier 1983, p. 17.

- ^ De Blomac 2003, p. 117.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Wagner 2006, p. 108.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 384.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 80.

- ^ Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, pp. 233–234.

- ^ De Blomac 2003, pp. 126–127.

- ^ De Blomac 2003, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b c Wagner 2006, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 229.

- ^ This is the premise of Milin, Gaël (1991). Le roi Marc aux oreilles de cheval. Publications romanes et françaises (in French). Vol. 197. Librairie Droz. ISBN 9782600028868..

- ^ De Blomac 2003, p. 118.

- ^ De Blomac 2003, p. 119.

- ^ De Blomac 2003, p. 125.

- ^ De Blomac 2003, p. 120.

- ^ Begoña Aguiriano in Collectif 1992, p. 9.

- ^ Begoña Aguiriano in Collectif 1992, p. 13.

- ^ Collectif 1992, pp. 513–520.

- ^ Schnitzer 1981, p. 65.

- ^ Sevestre & Rosier 1983, p. 21.

- ^ a b Wagner 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 68.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 400.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 424.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 118.

- ^ Sir James George Frazer, Le Rameau d'or, quoted by Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 227.

- ^ Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 227.

- ^ Boyer, Régis (1991). Yggdrasill: la religion des anciens Scandinaves. Bibliothèque historique (in French). Paris: Payot. p. 74-75. ISBN 2-228-88469-3

- ^ Boyer, Régis (1991). Yggdrasill: la religion des anciens Scandinaves. Bibliothèque historique (in French). Paris: Payot. p. 172-173. ISBN 2-228-88469-3

- ^ Paul Diel (1966). Le symbolisme dans la mythologie grecque (in French). Paris. p. 305.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 27.

- ^ Bridier 2002, p. 77.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 122–123.

- ^ F.G. Lorca, Romance à la femme infidèle, cité dans Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 229.

- ^ Clébert, Jean-Paul (1971). Bestiaire fabuleux (in French). Albin Michel. p. 109.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Bernard Sergent (1996). Homosexualité et initiation chez les peuples indo-européens (in French). Payot. pp. 82–96. ISBN 9782228890526..

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Papin, Yves Denis (2003). Connaître les personnages de la mythologie (in French). Jean-paul Gisserot. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9782877477178..

- ^ Bridier 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Garma, Ángel (1954). La Psychanalyse des rêves (in French). Translated by Madeleine Baranger. Presses universitaires de France. p. 252..

- ^ Nouvelle revue de psychanalyse: L'espace du rêve (in French). Vol. 5. Gallimard. 1972. p. 17. ISBN 9782070283132..

- ^ Willy Borgeaud and Raymond Christinger (1963). Mythologie de la Suisse ancienne. Vol. 1. Musée et institut d'ethnographie de Genève, Librairie de l'Université Georg. p. 85..

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 302.

- ^ Durand 1985, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 222.

- ^ Jung 1993, p. 465.

- ^ a b c Wagner 2006, p. 73.

- ^ a b Wagner 2006, p. 74.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 145.

- ^ Eiichiro, Ishida (1950). The kappa legend. A Comparative Ethnological Study on the Japanese Water-Spirit Kappa and Its Habit of Trying to Lure Horses into the Water. Folklore Studies. Vol. 9. Nanzan University. pp. i–11. doi:10.2307/1177401. JSTOR 1177401..

- ^ Baum 1991.

- ^ Sibona, Bruno (2006). Le cheval de Mazeppa: Voltaire, Byron, Hugo : un cas d'intertextualité franco-anglaise (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 63. ISBN 9782296003200..

- ^ (fr) J.J. Baude, "Les côtes de la Manche", Revue des deux Mondes, Au Bureau de la Revue des deux Mondes, vol. 3, 1851, p. 31 (read online).

- ^ Fernand Verge. "À la vitesse d'un cheval au galop ?". Pour la science. Retrieved 16 May 2011..

- ^ a b c Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 228.

- ^ Henry, René (1991). Hier en Ourthe-Amblève: Mythes et Destinées (in French). Éditions Dricot. p. 64. ISBN 9782870951484..

- ^ a b Wagner 2005, p. 274.

- ^ Maury, Louis-Ferdinand-Alfred (1857). Histoire des religions de la Grèce antique depuis leur origine jusqu'à leur complète constitution (in French). Vol. 1. Librairie philosophique de Ladrange. Retrieved 13 June 2009..

- ^ (fr) Pierre Dubois (ill. Roland and Claudine Sabatier), La Grande Encyclopédie des fées (1st ed. 1996) [details of editions] p. 103.

- ^ Raymond Bloch (1981). Quelques remarques sur Poséidon, Neptune et Nethuns. CRAI (in French). pp. 341–352..

- ^ Collectif 1992, p. 206.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 276.

- ^ (fr) Édouard Brasey (2008). La petite encyclopédie du merveilleux (in French). Paris: Le pré aux clercs. p. 177. ISBN 978-2-84228-321-6.

- ^ (fr) Pierre Dubois (ill. Roland and Claudine Sabatier), La Grande Encyclopédie des fées (1st ed. 1996) [details of editions] p. 102.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 39.

- ^ Dieterlein, Germaine (1988). Essai sur la religion des Bambara. Anthropologie sociale (in French). Éditions de l'Université de Bruxelles. p. 190..

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 67.

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 280.

- ^ a b c Wagner 2005, p. 299.

- ^ (fr) Pierre Grimal, Dictionnaire de la mythologie grecque et romaine, Paris, Presses universitaires de France, coll. "Grands dictionnaires", 1999 (1st ed. 1951) (ISBN 2-13-050359-4) pp. 66-67.

- ^ Delebecque 1951, p. 242.

- ^ Karmay, Samten G. (1998). The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals and Beliefs in Tibet. Mandala Publishing. pp. 413–415..

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 138.

- ^ Piétri, Jérôme; Angelin, Jean-Victor (1994). Le Chamanisme en Corse ou la Religion du Néolithique (in French). Éditions L'Originel. p. 84;116. ISBN 978-2-910677-02-2

- ^ a b c Wagner 2006, p. 164.

- ^ a b Ernest Jones, Le Cauchemar, cité dans Bridier 2002, p. 22.

- ^ a b Wagner 2006, p. 165.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Hatt, Mythes et dieux de la Gaule: Les grandes divinités masculines, cité par Wagner 2006, p. 164.

- ^ Mircea Eliade, Traité d'histoire des religions, 1949, cité dans Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 230.

- ^ Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1969, p. 23.

- ^ Sevestre & Rosier 1983, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Wagner 2006, p. 166.

- ^ Roux, Jean-Paul (1966). Flore et faune sacrée dans les Sociétés altaïques (in French). Maisonneuve et Larose. p. 343-344.

- ^ a b Wagner 2006, p. 167.

- ^ Durand 1985, p. 78.

- ^ Durand 1985, p. 84.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Hudson, D. Dennis (2008-09-25). The Body of God: An Emperor's Palace for Krishna in Eighth-Century Kanchipuram. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-19-536922-9.

- ^ Wagner 2006, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Dontenville, Henri (1950). Les dits et récits de mythologie française. Bibliothèque historique (in French). Payot. p. 35.

- ^ Clébert 1971, p. 102.

- ^ Gougaud 1973.

- ^ Nathalie Labrousse, "La fantasy: un rôle sur mesure pour le maître étalon", Asphodale, no 2, 2003, p. 146-151 (presentation online at NooSFere).

- ^ Université Paul Valéry (1979). Mélanges à la mémoire de Louis Michel (in French). p. 172.

- ^ a b Tsaag Valren 2012.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph (2009). More Celtic Fairy Tales. BiblioBazaar. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-559-11681-0

- ^ Afanassiev 1992, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Thoms 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Crofton Croker, Thomas (1834). Fairy legends and traditions of the south of Ireland. Vol. 47 de Family library. BiblioBazaar. pp. 129–133..

- ^ For example, in the Ballades et chants populaires (anciens et modernes) de l'Allemagne (in French). Charles Gosselin. 1841. p. 12. or in De Balzac, Honoré (1837). Clotilde de Lusignan. Méline, Cans & Co. p. 56..

- ^ De Troyes, Chrétien; de Denain, Wauchier (1968). Perceval et le Graal (in French). Vol. 27 de Triades. Supplément. Translated by Simone Hannedouche. Triades. p. 37.

- ^ Sansonetti, Paul-Georges (1982). Graal et alchimie (in French). Vol. 9 de L'Île verte. Berg International éditeurs. p. 152. ISBN 978-2-900269-26-8

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 46.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Martineau, Anne (2003). Le nain et le chevalier: Essai sur les nains français du moyen âge: Traditions et croyances (in French). Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 91-94. ISBN 978-2-84050-274-6

- ^ Doulet, Jean-Michel (2002). Quand les démons enlevaient les enfants: les changelins: étude d'une figure mythique: Traditions & croyances (in French). Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne. p. 301. ISBN 978-2-84050-236-4

- ^ (fr) Pierre Dubois; Roland and Claudine Sabatier (1992). La grande encyclopédie des lutins. Hoëbeke. p. Chapitre sur les lutins du foyer. ISBN 9782-84230-325-9..

- ^ Wagner 2005, p. 254.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 35.

- ^ (fr) Henri Dontenville, "Le premier cheval Bayard ou le dragon", in Les dits et récits de mythologie française, Payot, coll. "Bibliothèque historique", 1950 (online presentation), pp. 187-217.

See also[edit]

Related articles[edit]

External links[edit]

- D.A.R. Sokoll, "Symbolisme du cheval" archive

Bibliography[edit]

Exclusively devoted to horse symbolism[edit]

- (fr) Marie-Luce Chênerie, La symbolique du cheval, Lettres modernes, coll. "Archives des lettres modernes", 1972, 44 p. (OCLC 32484312, online presentation archive), chap. 163.