House of European History

This article contains promotional content. (March 2024) |

| House of European History (HEH) | |

|---|---|

| |

House of European History in the former Eastman Building, Leopold Park, Brussels | |

| |

| Former names |

|

| General information | |

| Type | History museum |

| Location | European Quarter, Leopold Park |

| Address | Rue Belliard / Belliardstraat 135 |

| Town or city | 1000 City of Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region |

| Country | Belgium |

| Coordinates | 50°50′24.1″N 4°22′42.6″E / 50.840028°N 4.378500°E |

| Inaugurated | 6 May 2017 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 8,000 m2 (86,000 sq ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Atelier Chaix & Morel et Associés |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

The House of European History (HEH) is a history museum and cultural institution in Brussels, Belgium, focusing on the recent history of Europe. It is an initiative by the European Parliament, and was proposed in 2007 by the Parliament's then-president, Hans-Gert Pöttering; it opened on 6 May 2017.[1]

As a cultural institution and exhibition centre, the House of European History intends to promote the understanding of European history and European integration through a permanent exhibition and temporary and travelling exhibitions. The museum houses a collection of objects and documents representative of European history, educational programs, cultural events and publications, as well as a wide range of online content. By interpreting history from a European perspective, it connects and compares shared experiences and their diverse interpretations. It also aims to initiate learning on transnational perspectives across Europe.

The museum is located in the former Eastman Dental Hospital, in Leopold Park, next to the Lycée Émile Jacqmain and close to the European institutions. This site is served by Brussels-Luxembourg railway station, as well as by the metro stations Maalbeek/Maelbeek and Schuman on lines 1 and 5.

Origins

[edit]The idea of creating a museum dedicated to European history was launched on 13 February 2007 by then-President of the European Parliament, Hans-Gert Pöttering, in his inaugural speech. One of the key objectives of the project was "to enable Europeans of all generations to learn more about their own history and, by so doing, to contribute to a better understanding of Europe's development, now and in the future."[2]

In October 2008, a committee of experts led by Professor Hans Walter Hütter, the Head of the House of the History of the Federal Republic of Germany,[2] submitted a report entitled "Conceptual Basis for a House of European History", which established the project's general concept and content and outlined its institutional structure.

In June 2009, the Bureau of the European Parliament decided to assign the former Eastman Dental Hospital to the future museum and, in July, launched an international architectural competition. On 31 March 2011, Atelier d'architecture Chaix & Morel et associés (France),[3] JSWD Architects (Germany)[4] and TPF (Belgium)[5] were awarded the contract to carry out the building's renovation and extension. With the backing of an expert board, which brought together internationally renowned specialists chaired by Professor Włodzimierz Borodziej, a multi-disciplinary team of professionals led by historian and curator Taja Vovk van Gaal was set up within the European Parliament's Directorate-General for Communication[6] to prepare the exhibitions and the structure of the future establishment.

Collection and scope

[edit]The House of European History gives visitors the opportunity to learn about European historical processes and events, and engage in critical reflection about their implications on the present day. It is a centre for exhibitions, documentation and information, which places processes and events within a wider historical and critical context, bringing together and juxtaposing the contrasting historical experiences of European people.

The originality of the project lies, therefore, in the endeavour to convey a transnational overview of European history, while taking into account its diversity and its many interpretations and perceptions. It aims to enable a wide public to understand recent history in the context of previous centuries that have marked and shaped ideas and values. In this way, the House aims to facilitate discussion and debate about Europe and the European Union (EU).

With a surface area of approximately 4,000 m2 (43,000 sq ft) at its disposal, the permanent exhibition is the museum's centrepiece. It also has 800 m2 (8,600 sq ft) for temporary exhibitions. Using 1500 objects and documents from over 300 museums and collections from across Europe and beyond, and an extensive range of media, it provides a journey through European history, principally that of the 20th century, with retrospectives on developments and events in earlier periods that were of particular significance for the whole continent. In this context, the history of European integration is exhibited in all its uniqueness and with all its complexity.[2]

Permanent exhibition

[edit]Spanning four floors, the permanent exhibition's galleries use objects and multimedia resources to take visitors on a thought-provoking narrative that focuses on European history, particularly during the 19th and 20th centuries. The permanent exhibition presents European political, economic, social and cultural history in a chronological layout, but with a thematic approach.

The exhibition begins with the myth of the goddess Europa, delving into Europe's ancient roots and the continent's heritage of shared traditions and achievements, before continuing through Europe's dramatic journey towards modernity in the 19th century and the rebuilding process following World War II. The final section challenges visitors to critically assess European history, its potential and its future.

In December 2012, in the context of the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to the EU,[7] it was decided that the Nobel medal and diploma will form part of the museum's permanent exhibition, as the first objects in its collection.[8][9]

-

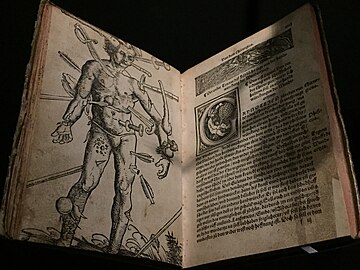

Field surgery book by Hans von Gersdorff and Hans Wechtlin (1526)

-

Seals and signatures on the Belgian copy of the General Act of the Berlin Conference (1885)

-

Bombshells from World War I, some converted into works of art by soldiers (1914–1918)

Temporary exhibitions

[edit]The House of European History's programme also includes a yearly temporary exhibition that provides the opportunity to expand upon or extend the themes and periods from the permanent exhibition. This allows for different or innovative types of exhibitions and varied content, in ways that are attractive to different audiences. As with the permanent exhibition, these temporary exhibitions take a transnational and interdisciplinary approach. They are in four languages (English, French, German and Dutch). The temporary exhibitions so far have been:

- Interactions: 5 May 2017 – 31 May 2018

- Restless Youth: 1 March 2019 – 29 February 2020

- Fake for Real: 1 October 2020 – 1 January 2022

- When Walls Talk!: 30 April 2022 – 13 November 2022

- Throwaway: 18 February 2023 – 14 January 2024

Digital

[edit]As part of the museum's mission to be accessible to audiences from across the continent and provide new means of conveying transnational history,[10] a range of digital products has been launched:

Location and accessibility

[edit]The former Eastman Dental Hospital, originally designed to house a dental clinic, was named after George Eastman, the American philanthropist and inventor of the Kodak camera.[11] His generous donations allowed the creation of dental centres in New York, London, Rome, Paris, Brussels and Stockholm, dedicated to providing free dental care for disadvantaged children.[12]

In 1933, the Eastman Foundation approached the Swiss-Belgian architect Michel Polak, known for his Art Deco style and particularly the famous Résidence Palace in Brussels, to design the new building.[12] Inaugurated in 1935,[13] the building is interesting both in terms of its engineering and its Art Deco elements. In the former children's waiting room, there is a series of murals by the painter Camille Barthélémy illustrating La Fontaine's fables.

Leopold Park, containing a number of historic buildings such as the Pasteur Institute, the former Solvay School of Commerce, the Solvay Institute of Sociology, and the Solvay Institute of Physiology, was listed in 1976. The Eastman Building itself is not listed. The dental clinic closed its doors before the building was converted into offices for the European institutions in the 1980s.

The museum is visitor-centred, wheelchair- and pushchair-friendly and open to all, in compliance with the European Parliament's policies relating to accessibility. To that end its main offers are presented via an interactive tablet in 24 languages, corresponding to the EU's official languages at the time of opening. Given that multilingualism is an expression of Europe's cultural diversity, the museum wants its visitors to experience its multilingual exhibits and services as one of the institution's main assets.

-

View of Leopold Park, the museum's location (European Parliament building in the background)

-

The former Eastman Dental Hospital pictured in 2009, before its refurbishment

-

The building in 2017, following refurbishment, with the roof extension

Management and direction

[edit]The House of European History was created at the initiative of the European Parliament but is run independently. The museum is directed by a Board of Trustees, chaired by the former president of the European Parliament Hans-Gert Pöttering. Its members have included Étienne Davignon, Włodzimierz Borodziej, Miguel Angel Martinez, Gérard Onesta, Doris Pack, Chrysoula Paliadeli, Hans-Walter Hütter, Charles Picqué, Alain Lamassoure, Peter Sutherland, Androulla Vassiliou, Diana Wallis, Francis Wurtz, Mariya Gabriel, Rudi Vervoort, Pierluigi Castagnetti, Sabine Verheyen, Johan Van Overtveldt, Domènec Ruiz Deveza, Harald Rømer, Pedro Silva Pereira, Martin Hojsík, Iliana Ivanova, Reinhard Bütikofer, Assita Kanko, Dimitrios Papadimoulis, Oliver Rathkolb and Klaus Welle.[14]

The Academic Committee, currently chaired by Oliver Rathkolb, comprises historians and museum curators. Its members have included Basil Kerski, John Erik Fossum, Constantin Iordachi, Emmanuelle Loyer, Sharon Macdonald, Daniela Preda, Kaja Širok, Luke van Middelaar, Daniele Wagener, Andreas Wirsching, Matti Klinge, Anita Meinarte, Hélène Miard-Delacroix, Mary Michailidou, Maria Schmidt, Anastasia Filippoupoliti, Louis Godart, Luisa Passerini, Wolfgang Schmale, Dietmar Preißler, Paul Basu, Gurminder K. Bhambra, Josep Maria Fradera, Olivette Otele and Steven van Hecke.[14]

The academic team that is responsible for curating exhibitions is led by Constanze Itzel.[14]

Estimated costs and funding

[edit]The cost of the development phase in 2011–2015 equalled €31 million[15] for the building's renovation and extension, €21.4 million for the permanent and the first temporary exhibitions (€15.4 million for fitting-out exhibition and other spaces, €6 million for multilingualism) and €3.75 million to build up the collection. The museum is funded by the European Parliament.

Controversies

[edit]Since its initial conception, the House of European History project has been controversial, especially in the UK. The alleged "attempt to find a single unifying narrative of the histories of 27 disparate member states" has been criticised by the British think tank Civitas, saying "the House of European History can achieve nothing but a disingenuous paradox, aiming to tell the history of all the 27 states, but in fact relating no history at all."[16]

More than the museum's contents, the museum's costs have come under fire. The costs were accused of having "more than doubled",[17] the projects initial £58 million cost estimate were accused to have more than doubled to £137 million. Some criticised the spending in the context of the 2008 recession, like the UKIP MEP Marta Andreasen who stated, in 2011, that "It defies both belief and logic that in this age of austerity MEPs have the vast sums of money to fund this grossly narcissistic project."[18]

The museum's permanent exhibition was criticised by Platform of European Memory and Conscience, which accused the museum of favourable bias in relation to the portrayal of communism in the Eastern Bloc.[19] The Acton Institute criticised the permanent exhibition for "erasing religion" as a factor in European history.[20]

See also

[edit]- Parlamentarium

- BELvue Museum

- European History Network

- List of museums in Brussels

- Art Deco in Brussels

- History of Brussels

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "European Parliament opens the House of European History on 6 May 2017 | News | European Parliament". 5 April 2017.

- ^ a b c COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS, House of European History (October 2008). "Conceptual Basis for a House of European History" (PDF). European Parliament. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ ChaixetMorel. "actualités". Chaix et Morel (in French). Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Aktuell". Aktuell (in German). Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Architecture – TPF GROUP". Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "About Parliament". About Parliament. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 2012". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Highlights" (PDF). 22 May 2023.

- ^ "EU leaders collect Nobel Peace Prize to put in £82m Museum of European History". 10 December 2012.

- ^ "MISSION & VISION". historia-europa.ep.eu. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Ancien Institut dentaire Eastman (Fondation Eastman) – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ a b Schoonbroodt 2003, p. 89–93.

- ^ "The Eastman Building: A Brussels architectural gem for the House of European History – Think Tank".

- ^ a b c "About Us | Organisation | House of European History museum". historia.europa.eu. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Busse, Nikolas. "EU-Museum: Stolz und Scham". Faz.net.

- ^ "Rewriting History". Civitas. 7 April 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Jones, Huw (16 December 2008). "The European Parliament plans to open a museum of the continent's history from "caveman to today," officials said Tuesday". Reuters.

- ^ Waterfield, Bruno (3 April 2011). "'House of European History' cost estimates double to £137 million". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Platform prepares critical report on the House of European History in Brussels and Platform calls for a broad debate and a change of the permanent exhibition of the House of European History, Platform of European Memory and Conscience

- ^ The House of European History erases religion, Acton Institute

Bibliography

[edit]- Kesteloot, Chantal (2018). "Exhibiting European History in the Museum: The House of European History". BMGN: Low Countries Historical Review. 133 (4): 149–161. doi:10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10618. ISSN 2211-2898.

- Schoonbroodt, Benoît (2003). Michel Polak de l'Art nouveau à l'Art déco (in French). Brussels: Commission de l'Environnement de Bruxelles-Ouest (CEBO).

Further reading

[edit]- Gehler Michael, Gonschor Marcus (2022). “A European Conscience: A biography of Hans-Gert Pöttering”. John Harper Publishing. ISBN 9781838089894

- Pöttering, Hans-Gert (2016). “United for the Better: My European Way”. John Harper Publishing. ISBN 9780993454967

- Dupont, Christine (2020). "Between Authority and Dialogue: Challenges for the House of European History", in Making Histories, De Gruyter Oldenbourg

- Quintanilha, Ines (2019). "Interactions in the House of European History", in Museological Review, Issue 23, p. 67–76.

- Van Weyenberg, Astrid (2019). "Europe on Display: A postcolonial reading of the House of European History" Politique européenne 2019/4 (No. 66), pp. 44–71

External links

[edit] Media related to House of European History at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to House of European History at Wikimedia Commons- Official website