Jacob Chemla

Jacob Chemla | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Jacob Chemla | |

| Born | May 1858 Tunis, Tunisia |

| Died | 1938 |

| Occupation(s) | Artist, author, journalist, translator |

| Known for | Ceramics |

Jacob Chemla (Arabic: يعقوب شملا; 1858–1938)[1] was a Tunisian Jewish ceramic artist, as well as an author, journalist and translator in Judeo-Tunisian Arabic.

Biography

[edit]While the Chemla family was originally from Djerba,[2] Jacob Chemla served as a legal representative for litigants of the Beth din of Tunis. Chemla was an active philanthropist in the Jewish community of Tunis, serving as a founding member of the Jewish Hospital of Tunis among other ventures.

Journalist, author, translator

[edit]

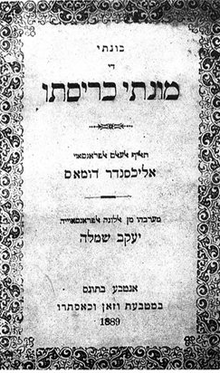

In 1878, Chemla began a career in journalism with his brother-in-law, Messaoud Maarek. For over thirty years, until 1925, he helped bring in a period of growth in Judeo-Tunisian Arabic literature. He published two novels, Amour et malice (Love and Malice) in 1912 and Les Cœurs purs (The Pure Hearts) in 1923. Chemla translated multiple titles into Hebrew and Judeo-Tunisian Arabic, including The Jews of Spain at the Time of the Inquisition and The Count of Monte Cristo, which he originally released as a serial and later in full during the 1880s.

Ceramics

[edit]Chemla is perhaps most well known around Tunisia for his activities in ceramics. His father Haïm Chemla was named by the Bey during the 1860s as the tax collector for the Artisans of Tunis (who would often pay in kind with donations of pottery). Haim Chemla would often pay the Bey the equivalent tax in cash while re-selling the pottery he had collected.[3]

Jacob Chemla followed in his father's footsteps around 1880, when he opened a shop in the Place des Potiers à Tunis,.[2][4] In 1887, the Tunisian government contracted him to help revive traditional ceramics.[2] In the Interwar period, production was moved to French Algeria and the United States, and the company presented at expositions in 1925, 1931 and 1937. Chemla's ceramic tiles decorated the homes of the rich in Tunis, Sidi Bou Said and La Marsa.[3] Starting in the 1910, his success extended to the USA and his ceramic tiles became features in the rich private homes architecture from Florida to California, but also decorated businesses such as the black-owned Renaissance Ballroom & Casino "Rennie" established by William H. Roach, the New-York Hotel McAlpin (the largest hotel in the world for its time), the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu,[5] but also the Santa Barbara Court House.[6]

He brought in his sons Victor (1892-1954), Albert (1894-1963) and Moïse (Mouche) (1897-1977) to the family business.[2] After the death of Victor and Albert's departure for Algeria in the 1930s, Moise succeeded his father and renamed the business Les fils de J. Chemla (Sons of Jacob Chemla), which operated as a family business until 1966. In the 1960s, President of Tunisia Habib Bourguiba contracted the company to install ceramic panels at Carthage Palace.

References

[edit]- ^ The date given in the file upon his award of the title Knight of the Legion of Honour in 1926.

- ^ a b c d Hatem Bourial (25 December 2015). "La saga de Jacob Chemla". webdo.tn (in French). Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Pot à couvercle". mahj.org (in French). Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Le papier à en-tête commercial de son entreprise indique 1881 comme date de fondation.

- ^ Stoolman, Jessie. "Southern California 'Spanish Revival' By Way of Tunis – Sephardic Los Angeles". Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ Santa Barbara Courthouse Docent Council. "Stairwell". sbcourthouse.org. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jacques Chemla; Monique Goffard; Lucette Valensi (2015). Un siècle de céramique d'art en Tunisie (in French). Paris: Éditions de l'Éclat. p. 207. ISBN 978-2841623778.

External links

[edit]- Marc-Alain Ouaknin; Monique Goffard; Lucette Valensi (13 December 2015). "Héritages tunisiens". franceculture.fr (in French). Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Monique Goffard; Moncef Guellaty; Francois Pouillon; Lucette Valensi; Michel Valensi (November 2015). "Les céramistes juifs de Tunis". akadem.org (in French). Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- André Chemla (October 2002). "L'histoire de la céramique des Chemla". chemla.org (in French). Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Monique Goffard; Lucette Valensi; Jacques Chemla. "La céramique : une histoire de famille". chemla.org (in French). Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.