John Wilson Bengough

John Wilson Bengough | |

|---|---|

Bengough in 1920 | |

| Born | 7 April 1851 |

| Died | 2 October 1923 (aged 72) Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Other names |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Awards | |

| Toronto City Councillor for Ward 3 | |

| In office 1907–1909 | |

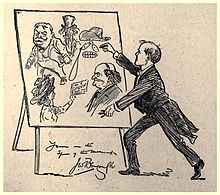

John Wilson Bengough (/ˈbɛŋɡɒf/;[1] 7 April 1851 – 2 October 1923) was one of Canada's earliest cartoonists, as well as an editor, publisher, writer, poet, entertainer, and politician. Bengough is best remembered for his political cartoons in Grip, a satirical magazine he published and edited, which he modelled after the British humour magazine Punch. He published some cartoons under the pen name L. Côté.

Born in Toronto in the Province of Canada to Scottish and Irish immigrants, Bengough grew up in nearby Whitby, where after graduating from high school he began a career in newspapers as a typesetter. The political cartoons of the American Thomas Nast inspired Bengough to direct his drawing talents towards cartooning; a lack of outlets for his work drove him to found Grip in 1873. The Pacific Scandal gave Bengough ample material to lampoon, and soon Bengough's image of prime minister John A. Macdonald achieved fame across Canada. After Grip folded in 1894, Bengough published books, contributed cartoons to Canadian and foreign newspapers, and toured giving chalk talks internationally.

Bengough was deeply religious and devoted himself to promoting social reforms. He supported free trade, prohibition of alcohol and tobacco, women's suffrage, and other liberal beliefs, but was opposed to Canadian bilingualism. Bengough had ambitions to run for office, though Liberal leader Wilfrid Laurier convinced him against running for Parliament; he served as alderman on the Toronto City Council from 1907 to 1909. The Canadian government listed Bengough as a Person of National Historic Significance in 1938 and he was inducted into the Canadian Cartoonist Hall of Fame in 2005.

Life and career

[edit]Early life (1851–73)

[edit]

Bengough's grandparents John (d. 5 April 1867), a ship's carpenter, and Johanna (née Jackson, d. 18 March 1859) were born in St Andrews in Scotland in the 1790s and immigrated with their children to Canada at an unknown date; they are known to have been in Whitby on Lake Ontario in the Province of Canada by the 1850s. They brought with them at least three children, including Bengough's father John (23 May 1819 in Scotland – 1899)[2] who became a cabinetmaker.[3] John Bengough was politically active: he advocated social reforms such as the Georgist single tax and had several Town Council appointments, though he never held political office. He used the title Captain, which suggests he may have sometime sailed ships out of Port Whitby.[2]

Bengough's father married Margaret Wilson, an Irish immigrant[4] born in Bailieborough in County Cavan,[5] and the couple had six children: five sons and a daughter.[2] John Wilson Bengough was the second,[6] born into the deeply Protestant family[7] on 7 April 1851 in Toronto,[3] where the elder Bengough had run a shop on Victoria Street in the 1840s.[8] It is not known when they moved to Toronto, but it is known that by 1853 the family had moved back to Whitby.[5]

Bengough attended Whitby Grammar School, where he was an average student;[6] he won a prize one year for general proficiency, for which he received a book titled Boyhood of Great Artists.[9] He was an avid sketcher,[10] a talent which caught the notice of his teacher, who presented Bengough with a set of paints one Christmas. Bengough credited this act with setting him on the path to a career as an artist.[6] Whitby residents later reminisced of the young Bengough drawing chalk portraits of his neighbours on fences.[11] He described himself as a "voracious reader", particularly of the Whitby Gazette, a didactic weekly that stressed Christian values.[7]

After graduation, Bengough tried his hand at a number of jobs, including photographer's assistant,[12] and he articled to a lawyer for some time[4] before getting a typesetting job at the Whitby Gazette.[12] The Gazette's editor was George Ham, an extroverted journalist who later worked as public relations chief for the Canadian Pacific Railway.[9] Bengough contributed short local-interest articles. In mid-1870, Ham issued a four-page daily to capitalize on interest in the Franco-Prussian War and commissioned Bengough to provide a serialized novel for it. The popular reception of The Murderer's Scalp (or The Shrieking Ghost of the Bloody Den) encouraged Bengough to devote himself to a journalism career.[12] The serial went unfinished because Ham cancelled the daily when the war died down.[5] The papers and magazines that came into the Gazette offices, in particular Harper's Weekly, introduced Bengough to the growing field of cartooning. Bengough reminisced,

I divided my time between mechanical duties for sordid wages and poetry for the good of humanity, and meanwhile I kept an eye on Thomas Nast the cartoonist.[12]

(18 August 1871)

Bengough considered the politically and socially aware Nast a "beau ideal" whose "moral crusade against abject wrong"—in particular his relentless Boss Tweed cartoons—inspired the young Bengough to "emulate Nast in the field of Canadian politics".[13] Bengough so admired the cartoonist that he sent a cartoon to Harper's of Nast confronting the Tammany Hall political machine, rendered in Nast's style,[14] to which the editor returned a positive response and an acknowledgement from Nast.[15]

At twenty, Bengough moved to Toronto and became a reporter on politician George Brown's newspaper The Globe.[16] The Liberal paper was the most influential in the country; Bengough's family had supported the Liberal Party since before Confederation, and these connections probably played a role in his getting the position at the paper.[17] Editorial cartooning had no presence in Canadian newspapers at the time and was not to have one until Hugh Graham brought the practice to his Montreal Star in 1876;[18][a] Bengough stated he did not consider the possibility of editorial cartooning at the time.[20] The lack of cartooning opportunities disappointed him, and he enrolled briefly in the Ontario School of Art, which he found pedantic and stifling;[16] he quit after one term.[20]

Grip (1873–94)

[edit]The legitimate forces of humor and caricature can and ought to serve the state in its highest interests, and that the comic journal which has no other aim than to amuse its readers for the moment, falls short of its highest mission.

— John Wilson Bengough, Grip, 7 January 1888[21]

Bengough told the following story of how he took up publishing: He had made a caricature of James Beaty, Sr., editor of the conservative Toronto Leader, and Beaty's nephew Sam found it so amusing that he made a lithographic copy for himself at the printer Rolph Bros. Impressed with his first exposure to lithography, and frustrated with the lack of opportunities to have his cartoons published, Bengough asked himself, "Why not start a weekly comic paper with lithographed cartoons?"[22] His brother Thomas remembered a somewhat different story in which Bengough first began distributing copies of his cartoons on the street.[22] Of his printed cartoons, only one of Liberal member Edward Blake has survived.[23]

In 1849–50[24] John Henry Walker's short-lived weekly Punch in Canada provided the first regular outlet for Canadian political cartooning;[b][26] others such as The Grumbler (1858–69), Grinchuckle (1869–70), and Diogenes (1868–70) did not last long, either. George-Édouard Desbarats's more conservative, Montreal-based Canadian Illustrated News (1869–83) lasted much longer. Bengough was to found the first major humour magazine in English Canada.[27]

A raven character in the Charles Dickens novel Barnaby Rudge inspired the name of the magazine Grip. Its pages carried political and social commentary along with satirical cartoons, and its debut issue of 24 May 1873 declared: "Grip will be entirely independent and impartial, always, and on all subjects." Bengough set the editorial policy and was the lead cartoonist.[28]

Grip's initial financing came from Toronto publisher Andrew Scott Irving.[29] Later in the year Bengough set up an office on 2 Toronto Street and with his four brothers formed the Bengough Brothers company.[30] Bengough continued to work at the Globe until Grip established itself. He used pseudonyms until he left the newspaper later in the year.[30] The editor's name appeared as a "Charles P. Hall" until Thomas Phillips Thompson took over as editor on 26 July under the pseudonym "Jimuel Briggs"; he lasted until the 6 September issue, when he printed a pro-alcohol article despite Bengough's prohibitionist views. The Toronto Globe's R. H. Larminie then took on co-editing duties as "Demos Mudge" with Bengough as "Barnaby Rudge".[c][24] Regular contributors other than Bengough included R. W. Phipps, who produced the greatest amount of Grip's poetry; Tom Boylan, who Bengough considered Grip's best humourist; Edward Edwards, who wrote sombre topical articles in contrast to the humour of the rest of the magazine; and William Alexander Foster who wrote scathing editorials about Oliver Mowat's Ontario Liberal Party, which contrasted with Bengough's position and lent credibility to the magazine's assertions of non-partisanship. Writers such as Peter McArthur got their start with Grip.[31]

(16 August 1873)

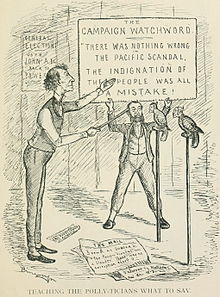

Grip's early issues attracted little notice.[32] The Hamilton Spectator declared it "dull ... When Grip dies, which will be soon, Toronto will be much more cheerful. ... Grip is what Punch would be with all the spirit left out".[33] Events arising from the Canadian federal election of 1872 shortly gave Bengough sufficient popular material to lampoon: accusations of bribery and other improprieties involving prime minister John A. Macdonald and business magnate Hugh Allan inflated into the Pacific Scandal, the most closely followed scandal in the young nation's history. Macdonald's features lent themselves to caricature and gave Bengough the chance to proselytize.[34] Circulation rose to about 2,000 copies per issue at the time; Bengough's brother Thomas reported that each new issue was eagerly awaited at the House of Commons.[35] A 23 August 1873 cartoon entitled "The Beauties of a Royal Commission: When shall we three meet again?" drew praise from newspapers across Canada, as well as from Liberal MP Lucius Seth Huntington in a speech to the House of Commons.[36]

Despite their Liberal leanings, in 1878 Bengough and Grip took the side of the proposed Conservative National Policy of high tariffs on trade with the US, against the governing Liberal stance of free trade. The issue contributed to the loss of Alexander Mackenzie's incumbent Liberals to Macdonald's Conservatives in the election of 1878,[37] despite Grip's prediction that Mackenzie would win again.[38] The magazine supported no party officially in its early years, but made its support for the Liberals explicit in the elections of 1887 and of 1891, after Wilfrid Laurier had become party leader. In the mid-1880s the Grip Printing and Publishing Company took on printing duties for the Ontario Liberal government. This support, however, resulted in no federal election wins.[39]

Grip had considerable influence on the public perception of politicians. That it was slanted in favour of Liberals and against Conservatives drove Conservative supporters to launch rival publications. The first was Jester, begun in 1878, which featured cartoons by Henri Julien that painted Macdonald in a benevolent light. Jester failed to find an audience to match Bengough's and folded the following year.[40] In 1886, Bengough reported a weekly circulation for Grip of 50,000.[35]

In March 1874, in the music hall of the Toronto Mechanics' Institute,[d] Bengough began giving comic chalk talk performances,[41] which he later toured across the country.[18] He impressed audiences with his ability to capture the likeness of members of the audience in a single penstroke.[42] He continued his chalk talks throughout his life and travelled with them to the US, Australia, New Zealand,[35] and Britain.[43] He published an autobiography titled Chalk Talks in 1922, the year before his death.[42]

Early Canadian feminist writer Sarah Anne Curzon made regular contributions to Grip.[44] At Bengough's request in 1882, she wrote the closet drama The Sweet Girl Graduate for the book The Grip Sack. The drama tells of a woman who disguises herself as a man to attend university at a time when women were barred in Canada from post-secondary education.[45]

In 1883, Frank Wilson took over management of the printing of Grip.[35] Thomas Phillips Thompson became associate editor. He shared with Bengough a radical political outlook and a taste for satire, though was less open to new ideas than Bengough, who was quick to attach himself to new causes. Thompson was anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, and anti-militarist.[46] In 1892, the managers of Grip passed the editorship from Bengough to Thompson[47] and Bengough's cartoons stopped appearing after the 6 August 1892 issue.[48] Years later, Bengough's brother Thomas blamed the board of directors at Grip, Inc., for the falling out over "general mismanagement",[49] which may have involved losses incurred in relation to a government contract.[48]

Grip's tone became increasingly strident: anti-French, anti-Catholic, pro-socialist. This, and an increased use of racial caricature, seem to have alienated readers.[50] Under the new editorship readership fell[47] until Grip ceased publication in July 1893.[49] Grip, Inc., sold off assets, such as its printing machines, to repay debts.[51]

Bengough revived Grip in 1894[47] under a new company called Phoenix Publishing with a partner named Bell who had newspaper publishing experience in Belleville.[51] They softened Grip's tone, but the content appeared rushed[52] and it lasted only from 4 January to 29 December 1894.[53] Macdonald had died in 1891, and Bengough blamed the publication's ill fortunes on the loss of such a target.[35]

Later life (1895–1923)

[edit]After Grip ceased publication, Bengough worked for the next quarter-century as a cartoonist for a variety of newspapers, including The Globe, The Toronto Evening Telegram, the Montreal Star, Canadian Geographic, the American The Public and The Single Tax Review, The Morning Chronicle[35] and Daily Express in England, and the Sydney Herald in Australia.[54]

Bengough continued to devote himself to political causes. He supported the Liberals' successful campaign in the federal election of 1896 with cartoons in the Toronto Globe and with a song he composed titled "Ontario, Ontario".[42] He belonged to numerous political and social clubs.[42] He was a founding member of the Royal Society of Canada in 1880,[55] to which the Governor General appointed him an Associate. He was professor of elocution at Knox College from 1899 to 1901.[42] He served as director of the Toronto Exhibition, auditor for the Canadian Peace and Arbitration Society,[56] member for three years of the board of directors of the Victoria Industrial School,[56] and president of the Toronto Single Tax Association, and took part in the People's Forum social activist group.[4]

In 1907, Bengough campaigned to join the Toronto City Council as an alderman for Ward 3. Major newspapers such as the Toronto Star promoted him, and the Toronto Daily World ran a photograph of him on its front page when he won.[56] He won again in 1908 and 1909.[4] He counted future Toronto mayor Horatio Clarence Hocken amongst his reformist allies on the Council[57] and promoted issues such as public ownership of hydroelectric power, but found little support for his ideas.[4] His successes included legislation restricting the issuing of liquor licenses, which found support when he made it an election issue in his 1909 campaign.[58]

In March 1909,[58] Bengough took a leave of absence from the Toronto City Council to tour Australia and New Zealand and gave up his post when he returned.[59] When the First World War broke out, he devoted his energies to promoting patriotism and the war effort, and supported conscription, a cause that was popular in English Canada but unpopular in Quebec and which ran counter to the Liberal Party position. Bengough nevertheless continued to support the party and used his cartoons to promote party leader William Lyon Mackenzie King in the federal election of 1921.[4]

Following a chalk-talk performance in Moncton, New Brunswick in 1922, Bengough suffered an attack of angina pectoris, attributed to overwork during a previous tour of Western Canada. He died of it on 2 October 1923[18] at his drawing board at his home on 58 St Mary Street in Toronto while working on a cartoon in support of an anti-smoking campaign.[4] At his memorial service on 22 November, the editor of the Hamilton Herald, Albert E. S. Smythe, declared him the "Canadian Dickens" and one of Walt Whitman's "great companions".[60]

Personal life

[edit]Bengough was of average height and had grey eyes and dark hair.[15] He married twice; neither marriage produced children. He married Helena "Nellie" Siddall in Toronto on 30 June 1880;[4] she died in 1902. He remarried to a friend from his school days, the widow[9] Annie Robertson Matteson, in Chicago on 18 June 1908.[4] Neither appears to have written about Bengough.[9]

Style

[edit]Bengough drew mainly political cartoons. His cartoons and writing tend towards the preachy and didactic; he believed that humour should serve the interests of the state rather than merely to amuse. Bengough tended in his writing towards satirical humour and puns, which George Ramsay Cook called "sometimes sophomoric".[61] He read Dickens, Shakespeare, and Carlyle with particular devotion.[55]

Bengough had little exposure to formal art education aside from one term at the Ontario School of Art.[62] His sketchy cartoons[4] derived from a mid-19th century engraving style;[63] while often drawn well, they were crowded in composition and sometimes borrowed from other sources.[4] Bengough could draw in contrasting styles, as evidenced by cartoons he did under the pseudonym of L. Côté.[4] As typical of political cartoonists of the time, Bengough aimed less at laughter than at social satire and depended more on readers' understanding of densely packed allusions.[64]

No other political figure came to life so vividly beneath Bengough's pen; no other cartoonists, even those who were far better draughtsmen were able to capture Macdonald's style and mannerisms as effectively.

— Terry "Aislin" Mosher and Peter Desbarats, The Hecklers: A History of Canadian Political Cartooning and a Cartoonists' History of Canada (1979)[65]

Bengough's cartoons are best remembered for fixing his renditions of Macdonald in the public imagination.[4] Bengough's bulbous-nosed[66] politician often appeared baggy-eyed with bottles of alcohol in his hands as a sombre symbol of corruption, in contrast to the work of John Henry Walker, another prolific caricaturist of Macdonald who depicted the prime minister's drunkenness to make light of him.[67] Bengough continued to hone his draftsmanship after Macdonald's death, but the wit and inspiration of his Macdonald cartoons continue to draw the most attention.[68]

Bengough's chalk talks have left less of a mark on the public memory, though audience members have passed down Bengough's renditions of them as heirlooms. Bengough delivered humorous anecdotes and made impressions as he caricatured audience members and well-known locals in a flamboyant manner, adding the identifying details only at the end.[43]

Politics

[edit]

There was a premier named John A.

Who, wishing in office to stay,

To one Allen did barter a great railway charter—

And dated his ruin from that day.— John Wilson Bengough, "Recollections of a Cartoonist", Bengough Papers, Volume VIII[69]

Bengough's reputation was as a supporter of the Liberal Party of Canada and its pro-democratic platform.[70] His family had been supporters since before Confederation; his father had supported Oliver Mowat and both his brother Thomas and sister Mary worked in Mowat's provincial government. Members of his family were to play roles in the Liberal Party into the twentieth century; Bengough and his brother Thomas had ties close enough with Wilfrid Laurier to ask for favours, and both were also close to William Lyon Mackenzie King.[17] Bengough had ambitions to run for Parliament, but Liberal leader Laurier convinced him against it;[4] Laurier also turned down a request of Bengough's for a Senate appointment as reward for a lifetime of Liberal support.[71]

Grip's political stance was one of disinterest, but a large portion of Bengough's income came from Liberal publications, and Macdonald and his Conservatives were favourite targets of Bengough's cartoon attacks, notably during the Pacific Scandal.[4] His association with the Liberals was so strong that Charles Tupper quipped in Parliament that Grip should change its name to Grit—a popular nickname for Liberal Party members. His best-remembered cartoons were those aimed at Macdonald and the Conservatives, but his criticisms targeted Liberals as well—Edward Blake had his subscription cancelled when he was the victim of a particular cartoon.[72] Macdonald's Conservative Daily Mail, launched in 1872, provided a rivalry with the Liberal Globe that provided fuel for Bengough's satire, as did infighting in the Liberal Party over The Globe, which allowed Bengough to distance himself to a degree from criticism of Liberal partisanship.[17]

Bengough was a proponent of such issues as proportional representation, prohibition of alcohol and of tobacco, the single tax[18] espoused by Henry George, and worldwide free trade. He held progressive views on women's suffrage;[73] in 1889 supported the Dominion Women's Enfranchisement Association efforts to have a bill proposed by Liberal MP John Waters that would have granted suffrage to Canadian women.[74] He expressed anti-imperialist ideals until the mid-1890s, after which he supported imperialism.[75] He supported Canada's involvement in the Second Boer War and First World War.[76] Bengough contributed to the ongoing debates concerning the development of a Canadian identity during the nation's early years.[77] He showed a marked ethnic nationalism in that he promoted English as the nation's sole official language, and the separation of church and state, a view that was directed particularly at the Catholic, French-speaking Québécois.[4] He depicted the Québécois as backward and Quebec politicians as always demanding money.[76] Bengough declared he looked forward to:[4]

when the monstrosity of a double official language and dual schools will be done away with throughout the whole country. Our real national life will date from that day.

— John Wilson Bengough, 7 April 1851, [4]

(29 August 1885)

Bengough had liberal views on race relations, and painted a picture of Canada as being more open to integration than the US during the Reconstruction era; according to David R. Spencer, his views on race were not likely widely shared in Canada at the time.[78] While Bengough sympathized with the plight of Canada's native peoples, he condemned the 1885 North-West Rebellion and called for the execution of Métis rebel leader Louis Riel, and celebrated Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton's victory at the Battle of Batoche in Saskatchewan with a poem.[4] His racial caricatures could, according to Carman Cumming, lead a modern reader to see him as "a racist chauvinist bigot":[79] they distort facial features and behaviour in ways typical of cartoons of the era and employ such derogatory terms as "coon" for blacks and "sheeny" for Jews.[80] Bengough called for restrictions on Chinese and Irish immigration[81] and his work shows a bias against immigrants who did not conform to Anglo-Saxon Protestant ideals.[82]

Bengough intended his didactic cartoons to impart moral instruction.[83] He expressed a deep devotion to religion. He had a Presbyterian upbringing, though as an adult he subscribed to no denomination. He promoted Christian ideals as solutions to social issues and thus, for example, opposed streetcars running on Sundays.[4] He proclaimed a Protestant work ethic widely expressed by Canadian artists and intellectuals of the late 19th century.[84] In his writing he frequently made statements about the role of Man in God's world,[85] and insisted that politics should conform to the will of God.[86] The editor of Canadian Methodist Magazine William Henry Withrow declared Bengough "an Artist of Righteousness"[87] who was "always on the right side of every moral question".[55]

Legacy

[edit]As Nast had in the US, Bengough succeeded in establishing editorial cartooning as a force in journalism in the late 19th century.[88] The church minister and Queen's College principal George Monro Grant called Bengough "the most honest interpreter of current events [Canada happens] to have" and declared he had "no malice in him" but had "a merry heart, and that doeth good like medicine".[1] The reformist English newspaper editor William Thomas Stead considered Bengough "one of the ablest cartoonists in the world".[89]

Outlets for political cartoons were mostly limited to illustrated magazines until they found a home in daily newspapers in the 20th century.[88] Bengough's busy, moralizing style began to fall out of favour by the 1890s in contrast to the cleaner style practised by such cartoonists as Henri Julien and Sam Hunter.[63] His caricatures nevertheless left an impression on the public consciousness in Canada for generations to follow.[90]

Bengough's caricatures continue to illustrate Canadian texts[71]—examples in which they are prominent include Creighton's biography John A. Macdonald (1952–55), Armstrong and Nelles' The Revenge of the Methodist Bicycle Company: Sunday Streetcars and Municipal Reform in Toronto, 1888–1897 (1977), and Waite's Arduous Destiny: Canada 1874–1896 (1971). Historians use the cartoons to demonstrate issues and attitudes of Bengough's era,[91] as well as for their artistic qualities, removed from their satirical contexts.[71] Historian Peter Busby Waite considered Grip "one of the most interesting sources for the social history of Ontario in the latter nineteenth century".[92]

Bengough's artistic legacy rests chiefly on his caricatures of Macdonald.[4] To Peter Desbarats and Terry Mosher, Bengough's bulbous-nosed caricatures of Macdonald as "ungainly, boozy, and corrupt ... engraved itself on the public mind, particularly in the days before newspapers published photographs of politicians".[66] Macdonald nevertheless deflated much of the power his caricaturists might have had as he often made light of his own alcoholism.[66] Bengough met the prime minister in person only once.[35]

Though his cartoons have continued to thrive, Bengough's life and career as a writer has drawn far less attention.[93] Bengough biographer Stanley Paul Kutcher considered his poetry "undistiguished".[54] Historian George Ramsay Cook commended Bengough's approach to have "nurtured the growth of social criticism in late Victorian Canada without much of that humourless self-righteousness that so often characterizes reformers".[92] Historian Carman Cumming's Sketches of a Young Country provides an in-depth analysis of Grip's politics.[94]

The town of Bengough, Saskatchewan, incorporated 15 March 1912, was named after the cartoonist.[95] On 19 May 1938, the Canadian government listed Bengough as a Person of National Historic Significance and dedicated a plaque to him at 66 Charles Street East in Toronto.[96] Bengough was inducted into the Canadian Cartoonist Hall of Fame in 2005.[97] The McMaster University Library in Hamilton, Ontario, holds the J. W. Bengough papers in its Division of Archives and Research Collection.[4]

Published works

[edit]

- 1875 – The Grip Cartoons. Rogers and Larminie[98]

- 1876 – The Decline and Fall of Keewatin. Grip Publishing Co.[98]

- 1882 – Bengough's Popular Readings: Original and Select. Bengough, Moore and Bengough[98]

- 1882 – The Grip-Sack: A Receptacle of Light Literature, Fun and Fancy. The Grip Printing and Publishing Co.[99]

- 1882 – Grip's Comic Almanac for 1882. Bengough, Moore and Bengough[100]

- 1886 – A Caricature History of Canadian Politics (two volumes). The Grip Publishing and Printing Co.[101]

- 1895 – Motley: Verse Grave and Gay. William Briggs[101]

- 1896 – The Up-to-date Primer. Funk & Wagnalls[98]

- 1897 – The Prohibition Aesop. Royal Templar Book and Publishing House[98][102]

- 1898 – The Gin Mill Primer. William Briggs[98]

- 1902 – In Many Keys. William Briggs[101]

- 1908 – On True Political Economy (The Whole Hog Book). American Free Trade League[98]

- 1922 – Chalk Talks. The Musson Book Co.[98]

No copies remain of the comic opera Hecuba; or Hamlet's Father's Deceased Wife's Sister, a comic opera with score by G. Barton Brown. Publisher F. F. Siddall registered it for copyright in 1885. The opera may have been an earlier version of Puffe and Co., or Hamlet, Prince of Dry Goods, for which an undated and possibly unpublished script exists, and for which Clarence Lucas had written a score that Bengough appears to have rejected.[103]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Montreal Star became the first Canadian newspaper to employ a full-time editorial cartoonist when it contracted Henri Julien in 1888.[19]

- ^ Bengough was to acknowledge Walker's precedence in his retrospective of Canadian political cartoons A Caricature History of Canadian Politics (1886).[25]

- ^ Bengough revealed he was "Barnaby Rudge" in the 29 March 1879 issue.[24]

- ^ Located on Church and Adelaide Streets.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ottawa Citizen staff 1975, p. 162.

- ^ a b c Winter 1978a, p. 7.

- ^ a b Kutcher 1975, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Cook 2005.

- ^ a b c Winter 1978b, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Kutcher 1975, p. 4.

- ^ a b Kutcher 1975, p. 5.

- ^ Blake 1985, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Cumming 1997, p. 32.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, p. 6.

- ^ Cumming 1997, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Kutcher 1975, p. 7.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Cumming 1997, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b Blake 1985, p. 15.

- ^ a b Kutcher 1975, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Cumming 1997, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Charlesworth 1927.

- ^ Spencer 2013, p. 57.

- ^ a b Blake 1985, p. 16.

- ^ Cook 2005; Mendelson 2007, p. 4.

- ^ a b Cumming 1997, p. 36.

- ^ Blake 1985, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Spencer 2013, p. 74.

- ^ Lamb 1998, p. 42–43.

- ^ Rabidoux 2010.

- ^ Bell 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Hulse 1994, p. 499; Cook 2005.

- ^ a b Blake 1985, p. 24.

- ^ Blake 1985, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, p. 12.

- ^ Blake 1985, p. 21.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Spencer 2013, p. 77.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, p. 14.

- ^ Cumming 1997, p. 67.

- ^ Cumming 1997, p. 69.

- ^ Cumming 1997, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Cumming 1997, p. 41.

- ^ a b Cumming 1997, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e Winter 1978c, p. 7.

- ^ a b Blake 1985, p. 35.

- ^ Blake 1985, p. 28.

- ^ Bird 2004, p. 47.

- ^ Cumming 1997, pp. 26, 28.

- ^ a b c Cumming 1997, p. 28.

- ^ a b Blake 1985, p. 30.

- ^ a b Blake 1985, p. 31.

- ^ Cumming 1997, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b Blake 1985, p. 32.

- ^ Cumming 1997, p. 178.

- ^ Blake 1985, p. 33.

- ^ a b Kutcher 1976, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Keys 1932, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Kutcher 1976, p. 40.

- ^ Kutcher 1976, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Kutcher 1976, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Cumming 1997, p. 228.

- ^ Keys 1932, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Cook 1985, p. 124.

- ^ Blake 1985, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Blake 1985, p. 34.

- ^ Lynch 1998–1999, p. 506.

- ^ Burr 2002, p. 518.

- ^ a b c Skelly 2015, p. 80.

- ^ Skelly 2015, p. 71.

- ^ Blake 1985, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, p. 11.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Pelletier 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Spencer 2013, p. 145.

- ^ Burr 2002, p. 551.

- ^ Burr 2002, p. 513.

- ^ a b Burr 2002, p. 541.

- ^ Burr 2002, p. 505.

- ^ Spencer 2013, p. 174.

- ^ Cumming 1997, p. 24; Mendelson 2007, p. 5.

- ^ Mendelson 2007, pp. 5, 9–11.

- ^ Mendelson 2007, pp. 8–9, 11.

- ^ Mendelson 2007, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, p. 19.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, p. 130.

- ^ Kutcher 1975, p. 18.

- ^ Burr 2002, p. 510.

- ^ a b Spencer 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Kutcher 1976, p. 31; Cook 1985, p. 124.

- ^ Cumming 1997, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Blake 1985, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Burr 2002, p. 506.

- ^ Blake 1985, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Burr 2002, p. 507.

- ^ McLennan 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Parks Canada staff.

- ^ Doug Wright Awards staff 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kutcher 1975, p. 267.

- ^ John Wilson Bengough in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- ^ John Wilson Bengough in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- ^ a b c Kutcher 1975, p. 267; Parks Canada staff.

- ^ John Wilson Bengough in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- ^ Hadfield 2004.

Works cited

[edit]- Bell, John (2006). Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe. Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-659-7.

- Bird, Kym (2004). Redressing the Past: The Politics of Early English-Canadian Women's Drama, 1880-1920. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2611-2.

- Blake, Dennis Edward (1985). J. W. Bengough and Grip the Canadian editorial cartoon comes of age (Master of Arts). Wilfrid Laurier University.

- Burr, Christina (December 2002). "Gender, Sexuality, and Nationalism in J.W. Bengough's Verses and Political Cartoons". Canadian Historical Review. 83 (4): 505–554. doi:10.3138/chr.83.4.505. S2CID 143792273.

- Charlesworth, Hector Willoughby (1927). "A Pioneer Canadian Cartoonist". The Canadian Scene. OCLC 4988585.

- Cook, Ramsay (1985). "'A Republic of God, a Christian Republic'". The Regenerators: Social Criticism in Late Victorian English Canada. University of Toronto Press. pp. 123–151. ISBN 978-0-8020-6609-1.

- Cook, Ramsay (2005). "Bengough, John Wilson". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto / Laval University. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- Cumming, Carman (1997). Sketches from a Young Country: The Images of Grip Magazine. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7646-5.

- Doug Wright Awards staff (2006). "Giants of the North: The Canadian Cartoonist Hall of Fame". Doug Wright Awards. Archived from the original on 5 August 2008.

- Hadfield, Dorothy (2004). "Puffe and Co., or Hamlet, Prince of Dry Goods (c. 1900)". Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. University of Guelph. Archived from the original on 26 June 2004. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- Hulse, Elizabeth (1994). "Andrew Scott Irving". In Cook, Ramsay; Hamelin, Jean (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 499–500. ISBN 978-0-8020-3998-9.

- Keys, D. R. (October 1932). "Bengough and Carlyle". University of Toronto Quarterly. 2 (1): 49–73. doi:10.3138/utq.2.1.49. S2CID 161833142 – via Project MUSE.

- Kutcher, Stanley Paul (1975). John Wilson Bengough: Artist of Righteousness (Master of Arts). McMaster University. hdl:11375/10063. Docket Paper 513.

- Kutcher, Stan (1976). "J. W. Bengough and the Millenium in Hogtown: A Study of Motivation in Urban Reform". Urban History Review. 1976 (2): 30–49. doi:10.7202/1019529ar.

- Lamb, Adrienne C. (1998). Fair Game: Canadian Editorial Cartooning (PDF) (Master of Arts). University of Western Ontario.

- Lynch, Gerald (Winter 1998–1999). "Carman Cumming, Sketches from a Young Country: The Images of 'Grip' Magazine". University of Toronto Quarterly. 68 (1): 505–506. doi:10.1353/utq.1998.0227 (inactive 1 November 2024) – via Project MUSE.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Mendelson, Alan (2007). "Grip Magazine and 'the Other': The Genteel Antisemitism of J. W. Bengough". Histoire Sociale / Social History. 40 (79). University of Ottawa / York University. ISSN 1918-6576.

- McLennan, David (2008). Our Towns: Saskatchewan Communities from Abbey to Zenon Park. University of Regina Press. ISBN 978-0-88977-209-0.

- Ottawa Citizen staff (10 January 1975). "You Asked Us". Ottawa Citizen. p. 162.

- Parks Canada staff. "Bengough, John Wilson National Historic Person". Parks Canada. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- Pelletier, Yves Y. (2010). The Old Chieftain's New Image: Shaping the Public Memory of Sir John A. Macdonald in Ontario and Quebec, 1891–1967 (PhD). Queen's University. hdl:1974/6251.

- Rabidoux, Ethan Georges (16 June 2010). "Street Gospels: Political Cartoons and Their Role in Canadian Democracy [i]". Friends of Canadian Broadcasting. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Skelly, Julia (Spring 2015). "The Politics of Drunkenness: John Henry Walker, John A. Macdonald, and Graphic Satire" (PDF). RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 40 (1): 71–84. doi:10.7202/1032757ar. S2CID 153445580. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Spencer, David R. (2013). Drawing Borders: The American-Canadian Relationship during the Gilded Age. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-0912-5.

- Winter, Brian (20 September 1978). "Brian Winter's Historical Whitby: Bengough Family". Whitby Free Press. p. 7.

- Winter, Brian (20 September 1978). "Brian Winter's Historical Whitby: J. W. Bengough (Part One)". Whitby Free Press. p. 7.

- Winter, Brian (4 October 1978). "Brian Winter's Historical Whitby: J. W. Bengough (Part Two)". Whitby Free Press. p. 7.

Further reading

[edit]- Bengough, Thomas (5 January 1937). Life and Work of J. W. Bengough, Canada's Cartoonist (PDF) (Speech). Bell Club address. Toronto. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

External links

[edit]- Works by John Wilson Bengough at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about John Wilson Bengough at the Internet Archive

- A Caricature History of Canadian Politics (1886) at HathiTrust

- On True Political Economy (The Whole Hog Book) (1908) at Wealth and Want