Karl Wilhelm Fricke

Karl Wilhelm Fricke | |

|---|---|

Fricke in 2011 | |

| Born | 3 September 1929 |

| Occupation(s) | Political journalist writer |

| Spouse | Friedelind Möhring (m. 1969) |

| Children | 2 |

Karl Wilhelm Fricke (born 3 September 1929) is a German political journalist and author. He has produced several of the standard works on resistance and state repression in the German Democratic Republic (1949–1990). In 1955, he became one of several hundred kidnap victims[1] of the East German Ministry for State Security, captured in West Berlin and taken to the east where for nearly five years he was held in state detention.[2][3]

From 1970 till 1994, he worked for (West) Germany's national radio station where he was influential as a political commentator and as the broadcaster's editor for "East-West affairs".

Life

[edit]Karl Oskar Fricke

[edit]His father was Karl Oskar Fricke. When the son was aged 16 his father was denounced by someone and arrested.[1] The family lived at that time in what had recently become the Soviet occupation zone of what had formerly been Germany. Karl Oskar Fricke had worked as a teacher, journalist and photographer. During the Nazi years he had worked in the little town of Hoym as the head of a press office and a "deputy propaganda chief" of the local Party Group. He had also involved himself with the (Nazi) Teachers' Association and written for the Teachers' Association journal. Karl Oskar Fricke was taken into investigative custody in June 1946. After four years in the Buchenwald internment camp he faced a mass trial in the Waldheim mega-jail[1] near Dresden. At the Waldheim Trials his turn lasted 30–40 minutes, before he was sentenced, along with another 3,400 internees processed in the space of a few weeks.[1] He received a further twelve-year prison sentence. However, he died 1952 because of an outbreak of dysentery and flu at the Waldheim penitentiary.[4]

Two new Germanys

[edit]Karl Wilhelm Fricke was permanently affected by his father's fate.[1] The son was unusual among his contemporaries in refusing to join the Free German Youth (FDJ / Freie Deutsche Jugend), which was in effect the youth wing of the region's Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED / Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands). The SED, formed only in April 1946, had already positioned itself as the ruling party, while the entire Soviet occupation zone had by October 1949 reverted to one- party government and redefined itself as the German Democratic Republic. Fricke's refusal to join the ruling party's youth wing left him with no opportunity formally to complete his secondary education. For a time he nevertheless worked as a language teaching assistant at the school where earlier his father had worked: there was a desperate shortage of Russian language teachers and Russian was the foreign language which Fricke had by now sufficiently mastered.[1] Life as a teaching assistant came to an end on 27 February 1949 when he was arrested at the school by two policemen, after a colleague had denounced him for criticising the Russians. The charge he faced was the standard one of conspiracy to commit high treason.[1] The police station in which he was held was a former villa that had not yet been converted and fortified, and he knew one of the arresting policemen from their childhoods.[1] While awaiting the commissar responsible for processing his case he managed to escape. That night he crossed the (at that stage still relatively porous) frontier which by now separated East and West Germany.[5]

In 1949 the occupation zones that had been under US, British and French control had been merged to form the German Federal Republic (West Germany), formally founded in May, nearly half a year before the launch of the German Democratic Republic to the east. Fricke's first months in West Germany were spent in a succession of refugee camps, originally established to accommodate Germans made homeless by frontier changes mandated at the Potsdam conference, and now increasingly filled also by refugees escaping the former Soviet occupation zone. After about five months in the refugee camp at Hannover-Kirchrode, thanks to the intervention of an academic called Fritz Voigt, he was offered a stipendium and the chance to study at the Academy for Work, Politics and Economics which had been set up on the north-west German coast at Wilhelmshaven in May 1949, and where Voigt had a professorship.[1] Fricke moved to Wilhelmshaven and started his studies at the end of the summer of 1949. A particular influence at Wilhelmshaven was Wolfgang Abendroth, a Marxist academic with a record of active opposition to Nazism who had nevertheless been persecuted in the German Democratic Republic and then expelled to the west when his ideas proved inconsistent with the objectives of the Soviet sponsored "Marxist" East German state. Fricke later recalled the impact on him of Abenroth's monthly informal seminars at Wilhelmshaven where students sat and discussed the works of Socialism's pre-Stalin heroes such as Rosa Luxemburg and Leon Trotsky.[1] Fricke would remain at Wilhelmshaven till 1953. His father had worked as a school teacher with a side-line in journalism, but Karl Wilhelm Fricke had by now resolved to make journalism his principal career. When he received news of his father's death Fricke was still studying at Wilhelmshaven, but he was already making a career as a political journalist at the same time, with political repression in the new East German state a particular area of expertise because of his personal experience. While he always maintained a reputation for well-researched and accurate reporting, the circumstances of his father's death were clearly no random misfortune: they profoundly strengthened his opposition to what he later described as a governmental structure politically predicated not on the democratically expressed will of the people but on "systematic injustice".[1][6]

Before completing his time at Wilhelmshaven Fricke had already begun his relocation to West Berlin, then the brittle front-line between intellectually incompatible competing power blocs. In Berlin there was a rich stream of material for a free-lance political journalist: Fricke's career in print continued to progress, now complemented by excursions into radio-journalism.[7] His themes included reports on the KgU, an anti-communist resistance group based in West Berlin,[8] and he also reported on the UFS,[9] a West Berlin-based human rights advocacy group widely believed to be funded and controlled by the CIA.[10] These organisations were primarily devoted to tracking the persecution of government opponents through use of the "justice system" in the German Democratic Republic.[11] In the German Democratic Republic itself Fricke's reports attracted far more interest than he would appreciate till much later. Officers of the recently established East Germany Ministry for State Security considered that his published articles, which they studied in close detail, were deeply damaging to the German Democratic Republic.[1]

Abduction and imprisonment

[edit]Karl Wilhelm Fricke was kidnapped in West Berlin on 1 April 1955.[7][12] Five days later State Security officials arrested his mother, Edith.[5]

Baited

[edit]In the course of his researches Fricke came across a man called Kurt Maurer,[12] a formerly Communist fellow-journalist who had spent time in a concentration camp during the Nazi years, and then following the war been interned by the Soviets.[1] Fricke was intrigued by the man's complex political background and was keen to get to know him better. Also Maurer had somehow obtained access to a source of books in the German Democratic Republic which were helpful in the context of Fricke's journalistic investigations.[12]

Hooked

[edit]On 1 April 1955 Fricke visited Maurer in his Berlin apartment to collect a book. Maurer was out, but his wife Anne-Marie was at home and offered Fricke a brandy. The third glass tasted odd, and after feeling unwell Fricke excused himself and went to vomit. Returning to the living room he still felt unwell and asked Mrs Maurer to call a taxi to take him home, before losing consciousness.[12] Fricke himself was able to reconstruct the ensuing 24 hours only through the reports of others, but it seems that he was placed unconscious in a sleeping bag which was then concealed in a caravan and taken across the border into East Berlin.[12] He had earlier mentioned his plan to visit Maurer to his fiancée, Friedelind Möhring, whom he had arranged to meet for dinner later that day. His disappearance was therefore quickly noticed and reported by his fiancée. Within a few hours Kurt Maurer was arrested, suspected of involvement in a kidnapping, but in the absence of better evidence against him, a West Berlin judge released him after 24 hours: meanwhile, across the city, Fricke was by now being interrogated without the benefit of a judge or even a lawyer being present.[12]

Kurt Mauer had not lied about his politically complicated past, but he had lied about his name, which was actually Kurt Rittwagen. His wife was Anne Marie Rittwagen.[1] The Stasi knew him as ""IM Fritz". For Fricke, then still only 25 years old, they used the code-name "Student".

Purpose

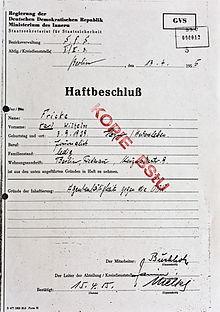

[edit]The pattern of Stasi kidnappings in West Berlin was not advertised at the time, and only became fully apparent in retrospect.[2] Years later it became clear that the abduction was carefully planned by the Stasi over many months. Three days before the abduction of Karl Wilhelm Fricke, its purpose was summarized by a Stasi officer called "Buchholz" in a memorandum that was opened up to a wider circle of researchers more than three decades later, after the Stasi archives had become accessible following reunification:

- Subject: Fricke

- The enemy activities of Fricke are that he obtained from persons in the German Democratic Republic documents and materials about leading Party Officers, leaders in the economy and of industry. [...] Furthermore, Fricke writes articles for the West German press. The purpose of arresting him is to identify and learn the methods by which our enemy sometimes succeeds in getting hold if the above mentioned items.[13]

Interrogation, verdict and sentence

[edit]

A succession of interrogation sessions over the next fifteen months ensued at the "Investigation Jail" at Berlin-Hohenschönhausen.[1] For most of that time Karl Wilhelm Fricke was held in solitary confinement and without access to any natural light. His interrogators were keen that he should name his illegal contacts in the German Democratic Republic, but they failed, according to Fricke, for the simple reason that there were none.[1] After nineteen weeks his interrogators knew nothing of significance beyond what they had been told to know before their victim had even been kidnapped. "The guilty man [had] under the cover name "Student" undertaken extensive crimes against the German Democratic Republic."[12] Having gone to the trouble of abducting and interrogating him, however, there was little logic in releasing Fricke, and in July 1956 he came before the Supreme Court in order to be condemned in a secret trial to fifteen years in prison for "Agitating for wars and boycotts".[7][14] The sentence was quite soon reduced to four years, which Fricke spent in solitary confinement at Brandenburg-Görden and Bautzen II.[1]

Looking back from more than half a century later, in 2013 Fricke opined that he had been fortunate not to have been kidnapped and interrogated by the Stasi a couple of years earlier than he was.[1] Joseph Stalin had died in March 1953, and East Germany underwent its own (violently suppressed) popular revolt later the same year. Khrushchev delivered one of the world's best remembered secret speeches in February 1956. Although it was not always immediately apparent, the political temperature in the power hubs of East Berlin and Moscow did become less nervous as the 1950s progressed, and there was an accompanying diminution in the savagery with which the regime treated its identified enemies.[1] Fricke was released in 1959 and ordered back to West Berlin: he was content to comply.

Mother

[edit]During the same period Karl Wilhelm Fricke's mother Edith received a two-year prison term in February 1956. It was asserted that she had known about and supported her son's activities.[5]

Back to work as a political journalist

[edit]After his release from prison in 1959 Fricke relocated to Hamburg and resumed his career as a free-lance journalist and writer.[7] However, print journalism was progressively losing out to the broadcast media at this time, and West Germany's broadcasting industry was even more heavily concentrated on Cologne then than now. It was to Cologne that Fricke moved in 1970.[7] Between 1970 and 1994 he worked as a senior (political) editor with Deutschlandfunk, the national radio station.[15] From East Germany the Ministry for State Security continued to observe him. A Stasi internal paper from 1985 notes:

- Fricke operates at Deutschlandfunk as head of the "East-west editorial" section. In his contributions and commentaries he slanders and distorts the political relationships in the German Democratic Republic (Party and state leadership, justice and sentencing). His books about the Stasi are intended to discredit the socialist security service internationally.[16]

The list of published articles and books from Karl Wilhelm Fricke is a long one. This is a selection .

- Geschichtsrevisionismus aus MfS-Perspektive (PDF; 132 kB)

- Die nationale Dimension des 17. Juni 1953. Bonn 2003.

- with Roger Engelmann: Der "Tag X" und die Staatssicherheit: 17. Juni 1953. Reaktionen und Konsequenzen im DDR-Machtapparat. Bremen 2003.

- with Peter Steinbach, Johannes Tuchel: Opposition und Widerstand in der DDR. München 2002.

- with Silke Klewin: Bautzen II. Leipzig 2001.

- with Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk: Der Wahrheit verpflichtet – Texte aus fünf Jahrzehnten zur Geschichte der DDR. Berlin 2000.

- with Roger Engelmann: Konzentrierte Schläge. Berlin 1998.

- Akten-Einsicht. Rekonstruktion einer politischen Verfolgung. Berlin 1996.

- Die DDR-Staatssicherheit. Entwicklung, Strukturen, Aktionsfelder. Köln 1989.

- Opposition und Widerstand in der DDR. Ein politischer Report. Köln 1984.

- with Gerhard Finn: Politischer Strafvollzug. Köln 1981.

- Politik und Justiz in der DDR. Zur Geschichte der politischen Verfolgung 1945–1968. Köln 1979.

- Warten auf Gerechtigkeit. Kommunistische Säuberungen und Rehabilitierungen. Köln 1971.

Later years

[edit]At the time when status of the German Democratic Republic as a stand-alone state collapsed, Karl Wilhelm was still based in Cologne and working for Deutschlandfunk (West Germany's / Germany's national radio station). He continued with them till 1994, the year of his 65th birthday. During the 1990s he also acted as an expert witness for two Bundestag formally constituted study commissions. One of these worked on the history and consequences of the one- party GDR dictatorship: the other looked at how to overcome the consequences of that one- party dictatorship in the ongoing unification process of which the "de jure" reunification of October 1990 was only one of many elements.[7]

For many years he also chaired the advisory boards of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial Museum and of the National Foundation for the Re-evaluation of the one-party GDR dictatorship.[7]

Evaluation

[edit]Today Fricke's books are standard works in the field of resistance and opposition, criminal justice and national security in the former German Democratic Republic (1949–1990).[17][18] In 2008 the senior East Germany scholar Johannes Kuppe, himself a colleague of Fricke's at Deutschlandfunk (and previously a pupil of Peter Christian Ludz) called Fricke the

- [de facto] pope for resistance, opposition and oppression. When it comes to the subject of repression in [former] East Germany, Fricke has in effect covered the entire field single handedly. Whatever there was that needed saying [on the subject], Fricke has already published it.[19][20]

Awards and honours

[edit]In 1996 the Free University of Berlin awarded Fricke an honorary doctorate for his work on political opposition in the former German Democratic Republic. In 2001 he was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (First class). In 2010 the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial Supporters' Association honoured him with the Hohenschönhausen Prize.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Rainer Burchardt (interviewer) [in German]; Karl Wilhelm Fricke (interviewee) (25 July 2013). "Der Deutschlandfunk war Rundfunk im Kalten Krieg". Deutschlandfunk, Cologne. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

{{cite web}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ^ a b More than 700 people were kidnapped in West Berlin and taken to the Communist Eastern zone of the city. See Falco Werkentin: Recht und Justiz im SED-Staat, 2nd edition, 1998, ISBN 3-89331-344-3

- ^ Isabell Fannrich (23 February 2015). "Von der Stasi im Westen verschleppt". A later estimate gives the number of people abducted by the Stasi from West Berlin during the 1950s as "about 400". Deutschlandfunk, Cologne. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Karl Wilhelm Fricke in an Interview with Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk. In: Karl Wilhelm Fricke: Der Wahrheit verpflichtet, Ch. Links, Berlin 2000, p. 14ff. Available online in Geschichte betrifft uns (History affects us) 1/2006, PDF, 267 KB.

- ^ a b c Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk. "Peaceful Revolution 1989/90: Karl Wilhelm Fricke". If anyone were to ask the Cologne-based journalist Karl Wilhelm Fricke how he saw his own part in the success of the East German revolution of 1989, he would answer with surprise that he had only informed people impartially of what went on. Yet for decades... Robert Havemann Society, Berlin. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "...[es] hat mich natürlich bestärkt in der Auffassung, nun wirklich zu ergründen, ist das ein zufälliges Schicksal oder ist das systembedingtes Unrecht?"

- ^ a b c d e f g "Fachbeirat Gesellschaftliche Aufarbeitung/Opfer und Gedenken: Dr. h.c. Karl Wilhelm Fricke, Vorsitzender". Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ "Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit". Mit dem Heißluftballon gegen das himmelschreiende Unrecht. Robert Havemann Society / Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung Medien- und Kommunikationszentrum Berlin. September 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Printed source given on webpage as: Siegfried Mampel: Der Untergrundkampf des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit gegen den Untersuchungsausschuß Freiheitlicher Juristen in West-Berlin (Schriftenreihe des Berliner Landesbeauftragten für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen DDR, Vol. 1). 4th edition, reworked and expanded. Berlin 1999. "Erwin Neumann". Stiftung Gedenkstätte Hohenschönhausen. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Affäre Nollau: Angriff aus dem Hinterhalt". Der Spiegel (online). 25 May 1974. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ Klaus Körner. "Politische Broschüren im Kalten Krieg (1967 bis 1963 – sic)". Berlin ist die Front. Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin. p. 2. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sven Felix Kellerhoff [in German] (September 2012). "Hauptstadt der Spione: Geheimdienste in Berlin im Kalten Krieg". Vier Jahre für den Kritiker. Die Entführung von Karl-Wilhelm. Berlin Story Verlag GmbH, Berlin. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ BStU-Akte ZA, AOP 22/67, Bd. (Vol) V, Blatt (page) 207: 28 March 1955

- ^ "Kriegs- und Boykotthetze"

- ^ Karl Wilhelm Fricke (9 November 2006). "Diktaturen-Vergleich muss sein". autobiographical note on the author at the foot of his article. Deutschlandfunk, Cologne. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ BStU, MfS, ZA, HA II/13-322, Bl. 30.

- ^ Eckhard Jesse (2008). Demokratie in Deutschland: Diagnosen und Analysen. Böhlau. p. 156. ISBN 978-3-412-20157-9.

- ^ Torsten Diedrich; et al. (1998). Im Dienste der Partei. Ch. Links Verlag. p. 412. ISBN 3-86153-160-7.

- ^ Jens Hüttmann (interviewer); Johannes Kuppe (interviewee) (2008). DDR-Geschichte und ihre Forscher. Akteure und Konjunkturen der bundesdeutschen DDR-Forschung. Metropol, Berlin. p. 257. ISBN 978-3-938690-83-3.

{{cite book}}:|author1=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Papst für Widerstand und Opposition und Unterdrückung. Fricke hat das Thema Repression in der DDR tatsächlich allein abgedeckt. Was zu sagen war, hat Fricke publiziert."

- ^ "Hohenschönhausen Prize of the Friends' Association of the Berlin‑Hohenschönhausen memorial museum". Förderverein Gedenkstätte Berlin‑Hohenschönhausen e.V. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

External links

[edit] Media related to Karl Wilhelm Fricke at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Karl Wilhelm Fricke at Wikimedia Commons

- 1929 births

- Living people

- People from Salzlandkreis

- People from the Free State of Anhalt

- German journalists

- German male journalists

- German editors

- German radio people

- 20th-century German historians

- German male writers

- Politics of East Germany

- Victims of human rights abuses

- Officers Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Prisoners and detainees of East Germany