Kepler-186f

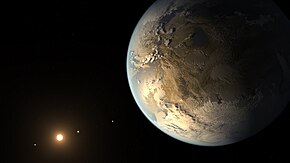

Artist’s depiction of Kepler-186f (foreground) as a rocky Earth-like planet in the habitable zone, with the Kepler-186 system visible in the background (bottom left). The actual appearance and composition of the exoplanet is not currently known. | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Elisa Quintana |

| Discovery site | Kepler space telescope |

| Discovery date | 17 April 2014 |

| Transit | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| 0.432 ± 0.01 AU[1] | |

| Eccentricity | 0.04[1] |

| 129.9444 ± 0.0012 d[1] 0.355772 y | |

| Inclination | 89.9[1] |

| Star | Kepler-186 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 1.17 ± 0.08[1] R🜨 | |

| Mass | 1.44+2.33 −1.12[2] ME |

| 1.17 (est.) g | |

| Temperature | Teq: 188 K (−85 °C; −121 °F) |

Kepler-186f[2][3] (also known by its Kepler object of interest designation KOI-571.05) is an Earth-sized exoplanet orbiting within the habitable zone of the red dwarf star Kepler-186,[4][5][6] the outermost of five such planets discovered around the star by NASA's Kepler space telescope. It is located about 580 light-years (180 parsecs) from Earth in the constellation of Cygnus.[7]

Kepler-186f orbits its star at a distance of about 0.43 AU (64,000,000 km; 40,000,000 mi) from its host star with an orbital period of roughly 130 days, and a mass and radius around 1.44 and 1.17 times that of Earth, respectively. As one of the more promising candidates for habitability, it was the first planet with a radius similar to Earth's to be discovered in the habitable zone of another star. However, key components still need to be found to determine its habitability for life, including an atmosphere and its composition and if liquid water can exist on its surface.

Analysis of three years of data was required to find its signal.[8] NASA’s Kepler space telescope detected it using the transit method (in which the dimming effect that a planet causes as it crosses in front of its star is measured), along with four additional planets orbiting much closer to the star (all modestly larger than Earth).[5] The results were presented initially at a conference on 19 March 2014[9] and some details were reported in the media at the time.[10] The planet was announced on 17 April 2014,[3] simultaneously with publication of a scientific paper in Science.[2]

Physical characteristics

[edit]Mass, radius and temperature

[edit]The only physical property directly derivable from the observations (besides the orbit) is the size of the planet relative to the central star, which follows from the amount of occultation of stellar light during a transit. This ratio was measured to be 0.021,[2] giving a planetary radius of 1.17 ± 0.08 times that of Earth.[3][5] The planet is about 11% larger in radius than Earth (between 4.5% smaller and 26.5% larger), giving a volume about 1.37 times that of Earth (between 0.87 and 2.03 times as large).

A very wide range of possible masses can be calculated by combining the radius with densities derived from the possible types of matter from which planets can be made. For example, it could be a rocky terrestrial planet or a lower density ocean planet with a thick atmosphere. A massive hydrogen/helium (H/He) atmosphere is thought to be unlikely in a planet with a radius below 1.5 R🜨. Planets with a radius of more than 1.5 times that of Earth tend to accumulate the thick atmospheres which make them less likely to be habitable.[11] Red dwarfs emit a much stronger extreme ultraviolet (XUV) flux when young than later in life. The planet's primordial atmosphere would have been subjected to elevated photoevaporation during that period, which would probably have largely removed any H/He-rich envelope through hydrodynamic mass loss.[2]

Mass estimates range from 0.32 ME for a pure water/ice composition to 3.77 ME if made up entirely of iron (both implausible extremes). For a body with radius 1.11 R🜨, a composition similar to that of Earth (i.e., 1/3 iron, 2/3 silicate rock) yields a mass of 1.44 ME,[2] taking into account the higher density due to the higher average pressure compared to Earth.[citation needed] That would make the force of gravity on the surface 17% higher than on Earth.

The estimated equilibrium temperature for Kepler-186f, which is the surface temperature without an atmosphere, is said to be around 188 K (−85 °C; −121 °F), somewhat colder than the equilibrium temperature of Mars.[12]

Host star

[edit]The planet orbits Kepler-186, an M-type red dwarf star which has a total of five known planets. The star has a mass of 0.54 M☉ and a radius of 0.52 R☉. It has a temperature of 3755 K and is about 4 billion years old,[1] about 600 million years younger than the Sun, which is 4.6 billion years old[13] and has a temperature of 5,778 K (5,505 °C; 9,941 °F).[14]

The star's apparent magnitude, or how bright it appears from Earth's perspective, is 14.62. This is too dim to be seen with the naked eye, which can only see objects with a magnitude up to at least 6.5 – 7 or lower.[15]

Orbit

[edit]Kepler-186f orbits its star with about 5% of the Sun's luminosity with an orbital period of 129.9 days and an orbital radius of about 0.40[1] times that of Earth's (compared to 0.39 AU (58 million km; 36 million mi) for Mercury). The habitable zone for this system is estimated conservatively to extend over distances receiving from 88% to 25% of Earth's illumination (from 0.23 to 0.46 AU (34 to 69 million km; 21 to 43 million mi)).[16] Kepler-186f receives about 32%, placing it within the conservative zone but near the outer edge, similar to the position of Mars in the Solar System.[2]

Habitability

[edit]

Kepler-186f's location within the habitable zone does not necessarily mean it is habitable; this is also dependent on its atmospheric characteristics, which are unknown.[17] However, Kepler-186f is too distant for its atmosphere to be analyzed by existing telescopes (e.g., NESSI) or next-generation instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope.[5][18] A simple climate model – in which the planet's inventory of volatiles is restricted to nitrogen, carbon dioxide and water, and clouds are not accounted for – suggests that the planet's surface temperature would be above 273 K (0 °C; 32 °F) if at least 0.5 to 5 bars of CO2 is present in its atmosphere, for assumed N2 partial pressures ranging from 10 bar to zero, respectively.[19]

The star hosts four other planets discovered so far, although Kepler-186 b, c, d, and e (in order of increasing orbital radius), being too close to their star, are considered too hot to have liquid water. The four innermost planets are probably tidally locked, but Kepler-186f is in a higher orbit, where the star's tidal effects are much weaker, so the time could have been insufficient for its spin to slow down significantly. Because of the very slow evolution of red dwarfs, the age of the Kepler-186 system was poorly constrained, although it is likely to be greater than a few billion years.[19] Recent results have placed the age at around 4 billion years.[1] The chance that it is tidally locked is approximately 50%.[20] Since it is closer to its star than Earth is to the Sun, it will probably rotate much more slowly than Earth; its day could be weeks or months long (see Tidal effects on rotation rate, axial tilt and orbit).[21]

Kepler-186f's axial tilt (obliquity) is likely very small, in which case it would not have tilt-induced seasons like Earth's. Its orbit is probably close to circular,[21] so it will also lack eccentricity-induced seasonal changes like those of Mars. However, the axial tilt could be larger (about 23 degrees) if another undetected non-transiting planet orbits between it and Kepler-186e; planetary formation simulations have shown that the presence of at least one additional planet in this region is likely. If such a planet exists, it cannot be much more massive than Earth as it would then cause orbital instabilities.[19]

One review essay in 2015 concluded that Kepler-186f, along with the exoplanets Kepler-442b and Kepler-62f, were likely the best candidates for being potentially habitable planets.[22]

In June 2018, studies suggest that Kepler-186f may have seasons and a climate similar to those on Earth.[23][24]

Follow-up studies

[edit]

Target of SETI investigation

[edit]As part of the SETI Institute's search for extraterrestrial intelligence, the Allen Telescope Array had listened for radio emissions from the Kepler-186 system for about a month as of 17 April 2014. No signals attributable to extraterrestrial technology were found in that interval; however, to be detectable, such transmissions, if radiated in all directions equally and thus not preferentially towards the Earth, would need to be at least 10 times as strong as those from Arecibo Observatory.[8] Another search, undertaken at the crowdsourcing project SETI-Live, reports inconclusive but optimistic-looking signs in the radio noise from the Allen Array observations.[26] The more well known SETI @ Home search does not cover any object in the Kepler field of view.[27] Another follow-up survey using the Green Bank Telescope has not reviewed Kepler 186f.[28] Given the interstellar distance of 490 light-years (151 pc), the signals would have left the planet many years ago.

Future technology and observations

[edit]At approximately 580 light-years (180 pc) distant, Kepler-186f is too far and its star too faint for current telescopes or the next generation of planned telescopes to determine its mass or whether it has an atmosphere. However, the discovery of Kepler-186f demonstrates conclusively that there are other Earth-sized planets in habitable zones. The Kepler spacecraft focused on a single small region of the sky but next-generation planet-hunting space telescopes, such as TESS and CHEOPS, will examine nearby stars throughout the sky. Nearby stars with planets can then be studied by the James Webb Space Telescope and future large ground-based telescopes to analyze atmospheres, determine masses and infer compositions.[21] Additionally the Square Kilometer Array would significantly improve radio observations over the Arecibo Observatory and Green Bank Telescope.[28]

Previous names

[edit]As the Kepler telescope observational campaign proceeded, an initially identified system was entered in the Kepler Input Catalog (KIC), and then progressed as a candidate host of planets to a Kepler Object of Interest (KOI). Thus, Kepler-186 started as KIC 8120608 and then was identified as KOI-571.[29] Kepler-186f was mentioned when known as KOI-571-05 or KOI-571.05 or using similar nomenclatures in 2013 in various discussions and publications before its full confirmation.[30]

Comparison

[edit]The nearest-to-Earth-size planet in a habitable zone previously known was Kepler-62f with 1.4 Earth radii. Kepler-186f orbits an M-dwarf star, while Kepler-62f orbits a K-type star. A study of atmospheric evolution in Earth-size planets in habitable zones of G-Stars (a class containing the Sun, but not Kepler-186) suggested that 0.8–1.15 R🜨 is the size range for planets small enough to lose their initial accreted hydrogen envelope but large enough to retain an outgassed secondary atmosphere such as Earth's.[31]

| Notable Exoplanets – Kepler Space Telescope |

|---|

Confirmed small exoplanets in habitable zones.

(Kepler-62e, Kepler-62f, Kepler-186f, Kepler-296e, Kepler-296f, Kepler-438b, Kepler-440b, Kepler-442b) (Kepler Space Telescope; 6 January 2015).[32] |

In popular culture

[edit]- Along with five other exoplanets, Kepler-186f was included in Civilization: Beyond Earth's exoplanet DLC as a playable map.[33]

- Dutch rock band The Hubschrauber [nl] named their 2017 album Kepler-186f after this exoplanet.[34]

- Kepler-186f is the location of a future earth colony in the short story "Stars" by Drew Hayden Taylor.

- In season 2 of the 2020 Animaniacs reboot, Kepler 186f, alongside Pegasi 51b & the fictional WB-1, is referenced in the song "Yakko's Big Idea"

- In season 12 of The Big Bang Theory episode "The Conjugal Configuration", Kepler 186F is shown on a poster in Neil deGrasse Tyson's office.

See also

[edit]- Habitability of red dwarf systems

- List of potentially habitable exoplanets

- Lists of astronomical objects

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "Kepler-186 f". NASA Exoplanet Archive. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Quintana, E. V.; et al. (18 April 2014). "An Earth-Sized Planet in the Habitable Zone of a Cool Star" (PDF). Science. 344 (6181): 277–280. arXiv:1404.5667. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..277Q. doi:10.1126/science.1249403. PMID 24744370. S2CID 1892595. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Michele; Harrington, J.D. (17 April 2014). "NASA's Kepler Discovers First Earth-Size Planet in The 'Habitable Zone' of Another Star". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (17 April 2014). "Scientists Find an 'Earth Twin', or Maybe a Wife". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Chang, Alicia (17 April 2014). "Astronomers spot most Earth-like planet yet". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014.

- ^ Morelle, Rebecca (17 April 2014). "'Most Earth-like planet yet' spotted Helper the Kepler". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014.

- ^ Bailer-Jones, C. A. L.; et al. (August 2018). "Estimating distances from parallaxes IV: Distances to 1.33 billion stars in Gaia Data Release 2". The Astronomical Journal. 156 (2): 58. arXiv:1804.10121. Bibcode:2018AJ....156...58B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aacb21. S2CID 119289017. Distance to Kepler 186, after taking into account light extinction

- ^ a b Quintana, Elisa (17 April 2014). "Kepler 186f – First Earth-sized Planet Orbiting in Habitable Zone of Another Star". SETI Institute. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Staff (16 March 2014). "EBI – Search for Life Beyond the Solar System 2014 – Exoplanets, Biosignatures & Instruments". EBI2014. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014. See session 19 March 2014 – Wednesday 11:50–12:10 – Thomas Barclay: The first Earth-sized habitable zone exoplanets.

- ^ Klotz, Irene (20 March 2014). "Scientists Home in on Earth-Sized Exoplanet". Discovery Communications. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014.

- ^ "NASA Kepler telescope discovers planet believed to be most Earth-like yet found". The Guardian. London. Press Association. 17 April 2014. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014.

- ^ "The Habitable Exoplanets Catalog – Planetary Habitability Laboratory @ UPR Arecibo". phl.upr.edu.

- ^ Fraser Cain (16 September 2008). "How Old is the Sun?". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Fraser Cain (15 September 2008). "Temperature of the Sun". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Sinnott, Roger W. (19 July 2006). "What's my naked-eye magnitude limit?". Sky and Telescope. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ "Kepler 186 f". hpcf.upr.edu. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (17 April 2014). "Earth's 'cousin' planet lies 500 light-years away". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014.

- ^ Greenfieldboyce, Nell (17 April 2014). "Scientists Spot A Planet That Looks Like 'Earth's Cousin'". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Bolmont, Emeline; Raymond, Sean N.; von Paris, Philip; Selsis, Franck; Hersant, Franck; Quintana, Elisa V.; Barclay, Thomas (27 August 2014). "Formation, tidal evolution and habitability of the Kepler-186 system". The Astrophysical Journal. 793 (1): 3. arXiv:1404.4368. Bibcode:2014ApJ...793....3B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/793/1/3. S2CID 118709918.

- ^ Ross, Hugh (15 April 2019). "Earth, an Extraordinary Magnet for Life". Reasons to Believe. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Staff (17 April 2014). "Kepler 186f – A Planet in the Habitable Zone (video)". Hangout On-Air. SETI Institute. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Paul Gilster, Andrew LePage (30 January 2015). "A Review of the Best Habitable Planet Candidates". Centauri Dreams, Tau Zero Foundation. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Mack, Eric (29 June 2018). "Two Earth-like exoplanets (Kepler 186f and Kepler 62f) now even better spots to look for life – Two of the earliest Earth-ish exoplanet finds are now more exciting targets in the search for habitable worlds beyond this rock". CNET. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ Shan, Yutong; Li, Gongjie (16 May 2018). "Obliquity Variations of Habitable Zone Planets Kepler-62f and Kepler-186f". The Astronomical Journal. 155 (6): 237. arXiv:1710.07303. Bibcode:2018AJ....155..237S. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aabfd1. ISSN 1538-3881. S2CID 59033808.

- ^ "Where the Grass is Always Redder - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ Farmer, Hontas (18 April 2014). "A better than 50/50 chance Kepler-186f has technological life". Science 20. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014.

- ^ See the fourth question at Kevvy, Mr. (20 March 2014). "The (Preliminary and Premature) Green Bank SERENDIP Fundraiser – Help SETI@Home Build a New (non-Arecibo) Receiver!". SETI@home. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014.

- ^ a b Siemion, Andrew P.V.; Demorest, Paul; Korpela, Eric; Maddalena, Ron J.; Werthimer, Dan; Cobb, Jeff; Langston, Glen; Lebofsky, Matt; Marcy, Geoffrey W.; Tarter, Jill (2013). "A 1.1 to 1.9 GHz SETI Survey of the Kepler Field: I. A Search for Narrow-band Emission from Select Targets". The Astrophysical Journal. 767 (1): 94. arXiv:1302.0845. Bibcode:2013ApJ...767...94S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/767/1/94. S2CID 119302350.

- ^ Rowe, Jason F.; et al. (27 February 2014). "Validation of Kepler's Multiple Planet Candidates. III: Light Curve Analysis & Announcement of Hundreds of New Multi-planet Systems". The Astrophysical Journal. 784 (1): 45. arXiv:1402.6534. Bibcode:2014ApJ...784...45R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/784/1/45. S2CID 119118620.

- ^ Glister, Paul (5 November 2013). "Earth-Sized Planets in Habitable Zone Common". Centauri Dreams. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. See comment by "Holger 16 November 2013 at 14:21".

^ redakce ["editor"] (6 August 2013). "Kepler (asi) našel obyvatelnou planetu o velikosti Země" [Kepler (probably) found a habitable planet the size of Earth] (in Czech). exoplanety.cz. Archived from the original on 20 August 2013.{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)

^ "Kepler: Erster Kandidat einer habitablen Exoerde Veröffentlicht" [Kepler: First candidate of a habitable Exoplanet Published]. Zauber der Sterne [Magic of the stars] (in German). 19 August 2013. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013.

^ Bovaird, Timothy; Lineweaver, Charles H. (1 August 2013). "Exoplanet Predictions Based on the Generalised Titius-Bode Relation". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 435 (2): 14–15. arXiv:1304.3341. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.435.1126B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1357. S2CID 15620163. - ^ Lammer, H.; Stökl, A.; Erkaev, N.V.; Dorfi, E.A.; Odert, P.; Güdel, M.; Kulikov, Yu.N.; Kislyakova, K.G.; Leitzinger, M. (13 January 2014). "Origin and Loss of nebula-captured hydrogen envelopes from "sub"- to "super-Earths" in the habitable zone of Sun-like stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 439 (4): 3225. arXiv:1401.2765. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.439.3225L. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu085. S2CID 118620603.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney; Chou, Felicia; Johnson, Michele (6 January 2015). "NASA's Kepler Marks 1,000th Exoplanet Discovery, Uncovers More Small Worlds in Habitable Zones". NASA. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Civilization: Beyond Earth". Steam.

- ^ "Nijmeegse band schiet album naar de maan". NOS op 3 (in Dutch). Nederlandse Omroep Stichting. 25 January 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

Vernoemd naar de eerst ontdekte planeet waar misschien wel menselijk leven mogelijk is

; 'google translated here'

External links

[edit]- NASA – Mission overview.

- NASA – Kepler Discoveries – Summary Table.

- NASA – Kepler-186f at The NASA Exoplanet Archive.

- NASA – Kepler-186f at The Exoplanet Data Explorer.

- NASA – Kepler-186f at The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia.

- Habitable Exolanets Catalog at UPR-Arecibo.

- NASA – Kepler 186f – SETI Institute – A Planet in the Habitable Zone (video) Archived 18 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine 2014.

- NASA – NASA Press kit Archived 18 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine.