Lovro Šitović

Lovro Šitović | |

|---|---|

| Born | Hasan Šitović c. 1682 Ljubuški, Herzegovina, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 28 February 1729 (aged 46–47) Sebenico, Dalmatia, Republic of Venice |

| Years active | Early modern period |

| Known for | Authored Latin grammar for Croat students |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Grammar |

| Main interests | |

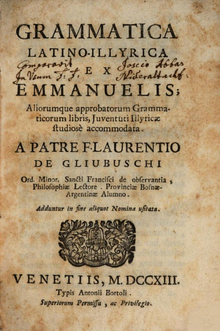

| Notable works | Grammatica Latino-Illyrica (1713) |

| Influenced | Toma Babić,[1] Matija Antun Relković[2] |

| Signature | |

Lovro Šitović OFM (c. 1682 – 28 February 1729) was a Croatian Franciscan, grammarian and writer. In 1713, he published Grammatica Latino-Illyrica, which was the most-influential Latin-grammar text among Croats of its time.

Šitović was a native of Ljubuški in Ottoman Herzegovina; he was born into a Muslim family and converted to Catholicism at a young age. He joined the Bosnian Franciscans, and served in Venetian Dalmatia as a professor of philosophy and theology. Besides publishing Latin grammar texts, Šitović was a popular author whose works were widely read by Catholics, especially those in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Early life

[edit]Šitović was born in Ljubuški in Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina.[3][4][5] He belonged to a Muslim family, and was given the first name Hasan.[5] At the time, the Morean War between the neighbouring Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire, was in its early stages. During the war, Christian hajduks from the Venetian Dalmatia intruded into and plundered the adjacent Herzegovinian and Bosnian areas. During one of these intrusions, in either 1690 or 1694, the hajduk harambaša Šimun Talajić Delija kidnapped Šitović's father.[5] His father left Šitović to the hajduks as a pledge while he collected the demanded ransom.[3][5] While a hostage, Šitović learned how to read and write,[3] and developed sympathies for Christianity.[5] He was taken home when his father paid the ransom but shortly after, Šitović left his home to return to his former captor Delija. Delija took Šitović to the Franciscan friary in Zaostrog, where Šitović was allowed to remain and learn about Christianity.[6] On 2 February 1699, at the age of 17,[7] Šitović was christened by Fiar Ilija Mamić as Stipan.[6]

Franciscan Order

[edit]

Šitović became interested in living a consecrated life. He was sent to a novitiate in Našice in Slavonia, where on 10 April 1701, he put on the Franciscan habit and chose Lovro as his religious name.[8] Šitović was then sent for education in Italy, where he stayed until 1708. While in Italy, he was ordained to the priesthood in 1707. After finishing his education, in 1708, Šitović became a philosophy professor and educator for the seminarians at the Makarska friary. When the philosophy studies in Makarska were discontinued in 1715, Šitović was transferred to the Šibenik friary to teach theology. In 1718, Archbishop Stefano Cupilli of Split invited him to teach theology at the archdiocesan seminary in Split, Croatia. In 1720, Šitović was awarded the title of general lector and honorary definitor (assistant) of the Franciscan Province of Bosnia. After philosophy studies were reintroduced in Makarska in 1724, Šitović returned there to teach.[9] During these years, Šitović risked his life during the Ottoman–Venetian War (1714–1718) and the Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718) by hearing soldiers' confessions, giving last rites to the dying, and burying the dead—especially during the defence of Sinj and liberation of Imotski. To reward him, Sebastiano Mocenigo, the provveditore general of Dalmatia, gave land near Sinj to Šitović's brother's wife and nephew, who had converted to Christianity.[10]

In 1723, Šitović became an examiner for professorships in philosophy and examiner of seminarians in theology before their priestly ordination in 1726.[clarification needed] In 1727, he was appointed an administrator of a Franciscan inn in Dorbo near Split. Šitović died in Šibenik while preaching there during Lent. Along with Jesuit Ardelio Della Bella, Šitović is considered to have been one of the greatest preachers of the time in southern Croatia.[10]

Works

[edit]Šitović was a Baroque author,[11] and wrote in the Shtokavian Ikavian dialect[12][13] becoming one of the most-popular authors of the older period of Croatian literature.[14] His works were widely read in Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina.[15]

In Venice in 1713, Šitović published a Latin-grammar text called Grammatica Latino-Illyrica, which was written for Illyrian schoolchildren[16] using the Shtokavian dialect,[17] which referred to as Illyrian.[17][18] Šitović's grammar follows the tradition of Manuel Álvares.[1][3][16][17][19] The influence of Jakov Mikalja is noticeable in Šitović's use of terms and his model for creating new ones. Toma Babić had published his work Prima grammaticae institutio pro tyronibus Illiricis accomodata the previous year;[16] its incompleteness was noted in educational practice; Šitović, being unsatisfied with it, published his grammar text the following year.[1][20] Šitović's text is more extensive[3][16] and became widely accepted.[16] Compared to Babić's, Šitović's grammar text is richer in syntactic rules.[21] When publishing the second edition of his grammar in 1745, Babić used a lot of material from Šitović's work.[19] Šitović and Babić used Croatian as a metalanguage for the grammatical narrative when adapting Latin grammar into other languages; this is recognised as a significant innovation.[22]

Explaining his motivation for writing the grammar, Šitović wrote:

My dear and lovely reader, do not be surprised at this effort of mine, even if it is a small one, because when you understand the reason: ... It is already evident to you that many nations, that is, the French, the Spanish, the Italians, the Germans, the Hungarians, etc., learn grammar more easily than we Croats ... because they print grammars translated into their language ... because we do not have grammars translated into our language. Even though some grammar teachers [referring to Babić][23] have translated the declensions of names and conjugations of Croatian verbs ...[24]

Grammatica Latino-Illyrica had two more editions, which were published in 1742 and 1781.[3][21][25] Šitović's grammar text was still in use more than a century after its publication[10][23] by many generations of Franciscans, young adults, adolescents and children who were educated at Franciscan friaries and parishes[25] outside his own Franciscan Bosnian Province.[23]

Šitović's other work[7] Pisna od pakla (A song of hell), a song in five cantos,[26] was published in 1727 in Venice.[7] It was also written in Shtokavian dialect,[15] in "Croatian language and singing",[18][27] and was dedicated to "people who speak Croatian".[18][28] Šitović used ten-syllable verse, a model that would dominate folk and artistic literature in the following decades.[15][29] In this poem, Šitović decries folk songs, their un-Christian heroes, and their praise of love and wine. He urges the clergy to eradicate such songs, and to promote those calling for devotion and penitence.[30] Slobodan Prosperov Novak characterised Pisna od pakla as a "vulgarised Divine Comedy" that was easily accessible to people "in Bosnian backwoods".[15] Ivo Andrić wrote of it as Šitović's "most interesting work", however "frequently irregular and quite devoid of any beauty" it may be.[4] Another edition of Pisna od pakla titled Pisma od pakla was published in the mid-18th century; this second edition has confused historians because it gives 1727 as its publication date and it was long assumed the work only had one edition.[31]

Šitović's other works include Doctrina christiana et piae aliquot cantilenae ("Christian doctrine and some pious hymns"), which was published in 1713 in Venice;[3][10] Promišljanja i molitve ("Reflections and prayers"), which was published in 1734 in Buda;[10] and List nauka krstjanskog ("A paper of the Christian teaching"), which was published in 1752 in Venice.[3][7]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c Stolac 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Despot 2009, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Despot 2009, p. 49.

- ^ a b Andrić 1990, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e Pavičić 2008, pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b Pavičić 2008, pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b c d Pavičić 2008, p. 194.

- ^ Pavičić 2008, p. 196.

- ^ Pavičić 2008, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b c d e Pavičić 2008, p. 197.

- ^ Katičić 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Kuna 1990, p. 118.

- ^ Lisac 2014, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Meić 2014, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Prosperov Novak 2003, p. 137.

- ^ a b c d e Horvat & Kramarić 2020, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Knežević 2007, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Fine 2010, p. 341.

- ^ a b Boban, Grubeša & Jurčić 2022, p. 47.

- ^ Boban, Grubeša & Jurčić 2022, p. 45.

- ^ a b Boban, Grubeša & Jurčić 2022, p. 41.

- ^ Horvat & Perić Gavrančić 2023, p. 138.

- ^ a b c Boban, Grubeša & Jurčić 2022, p. 46.

- ^ Marić 2021, p. 49: Moi Draghi, i mili Sctioce, nemoj se cudit ovomu momu, ako i malahnu trudu; jer kad razumisc razlog ... Jurje tebi ocito, da mnozi narodi to jest, Franczezi, Spagnoli, Italianczi, Nimczi, Ungari etc. lascgne nauce Grammatiku, nego mi Hrvati ... jerbo oni stampaju Grammatike u svoje vlastite jezike istomacene (...) jerbo mi neimamo Grammatikah u nasc jezik istomacenih. I premda jessu kojgodi Naucitegli Grammatike, istomacili Declitanitone Imenah, i Conjugatione Verabah harvaski...

- ^ a b Marić 2021, p. 46.

- ^ Meić 2020, p. 418.

- ^ Grčević 2009, p. 218: "i sloxi ú Harvatski jezik, i pivanye ..."

- ^ Meić 2020, p. 418: "puku ki govori hrvatskim jezikom..."

- ^ Andrić 1990, p. 50.

- ^ Andrić 1990, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Grčević 2009, p. 217.

References

[edit]Books

[edit]- Andrić, Ivo (1990). The Development of Spiritual Life in Bosnia Under the Influence of Turkish Rule. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822382553.

- Boban, Luciana; Grubeša, Josip; Jurčić, Jelena (2022). Polivalentnost latinskog jezika u Bosni i Hercegovini: Specifičnosti latiniteta u Hercegovini [Polyvalence of the Latin language in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Specificities of Latinity in Herzegovina] (in Croatian). Mostar: University of Mostar. ISBN 9789958162183.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (2010). When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472025602.

- Grčević, Mario (2009). "Izdanja Šitovićeve epske pjesme" [Editions of Šitović's epic poem]. In Knezović, Pavao (ed.). Zbornik radova sa znanstvenoga skupa "Lovro Šitović i njegovo doba", Šibenik - Skradin, 8.-9. svibnja 2008 [Proceedings from the scientific conference "Lovro Šitović and his era", Šibenik - Skradin, 8-9 May 2008] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Hrvatski studiji Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. ISBN 9789536682812.

- Katičić, Radoslav (2009). "Kulturnopovijesne koordinate fra Lovre Šitovića" [Cultural and historical coordinates of Fr. Lovra Šitović]. In Knezović, Pavao (ed.). Zbornik radova sa znanstvenoga skupa "Lovro Šitović i njegovo doba", Šibenik - Skradin, 8.-9. svibnja 2008 [Proceedings from the scientific conference "Lovro Šitović and his era", Šibenik - Skradin, 8-9 May 2008] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Hrvatski studiji Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. ISBN 9789536682812.

- Lisac, Josip (2014). "Šime Starčević i novoštokavski ikavski dijalekt" [Šime Starčević and the Novoštokavian Ikavian dialect]. In Vrcić-Mataija, Sanja; Grahovac-Pražić, Vesna (eds.). Šime Starčević i hrvatska kultura u 19. stoljeću: Zbornik radova sa znanstvenog skupa održanog u Gospiću 7. i 8. prosinca 2012 [Šime Starčević and Croatian culture in the 19th century: Proceedings from the scientific conference held in Gospić on 7 and 8 December 2012] (in Croatian). Mostar: Hercegovačka franjevačka provincija Uznesenja BDM. ISBN 9789958876301.

- Meić, Perina (2014). Izazovi (hrvatska književnos u BiH i druge teme) [Challenges (Croatian literature in BiH and other topics)] (in Croatian). Zagreb-Sarajevo: Synopsis. ISBN 9789537968229.

- Meić, Perina (2020). "Hrvatska književna tradicija u BiH - poetska veselka Koromana, pisci ljubuškog kraja" [Croatian literary tradition in Bosnia and Herzegovina – the poetics of Veselko Koromana, writers from the Ljubuški region]. In Jolić, Robert (ed.). Humački zbornik: radovi sa znanstvenog skupa povodom 150 godina od početka izgradnje franjevačkog samostana na Humcu (20. i 21. listopada 2017.) [Humac collection: papers from the scientific meeting on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the construction of the Franciscan friary in Humac (20 and 21 October 2017)] (in Croatian). Mostar: Hercegovačka franjevačka provincija Uznesenja BDM. ISBN 9789958876301.

- Prosperov Novak, Slobodan (2003). Povijest hrvatske književnosti: Od Bašćanske ploče do danas [History of Croatian literature: From the Bašćanska tablet to the present day] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Golden marketing. ISBN 9532120335.

- Stolac, Diana (2009). "Gramatika Lovre Šitovića u kontekstu hrvatske gramatikologije" [Lovro Šitović's grammar in the context of Croatian grammar]. In Knezović, Pavao (ed.). Zbornik radova sa znanstvenoga skupa "Lovro Šitović i njegovo doba", Šibenik - Skradin, 8.-9. svibnja 2008 [Proceedings from the scientific conference "Lovro Šitović and his era", Šibenik - Skradin, 8-9 May 2008] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Hrvatski studiji Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. ISBN 9789536682812.

Journals

[edit]- Despot, Loretana (2009). "Lovro Šitović i slavonske gramatike 18. stoljeća" [Lovro Šitović and Slavonian grammars of the 18th century]. Riječ: časopis za slavensku filologiju (in Croatian). 2: 48–58. ISSN 1330-917X.

- Horvat, Marijana; Kramarić, Martina (2020). "Jezikoslovno nazivlje u gramatikama M. A. Relkovića i G. Vinjalića" [Linguistic nomenclature in the grammars of M. A. Relković and G. Vinjalić]. Rasprave: Časopis Instituta za hrvatski jezik i jezikoslovlje (in Croatian). 6 (1): 93–109. doi:10.31724/rihjj.46.1.5. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- Horvat, Marijana; Perić Gavrančić, Sanja (2023). "On Historical-Grammatical Terminology in the RETROGRAM Project". Collegium Antropologicum. 47 (2): 137–144. doi:10.5671/ca.47.2.5. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- Knežević, Sanja (2007). "Nazivi hrvatskog jezika i dopreporodnim gramatikama" [Names of the Croatian language and pre-Renaissance grammars]. Croatica et Slavica Iadertina (in Croatian). 3 (3): 41–69. doi:10.15291/csi.359. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- Kuna, Herta (1990). "Bosanskohercegovačka franjevačka koine XVII i XVIII vijeka i njena dijalekatska baza" [Bosnian-Herzegovinian Franciscan Koine of the 17th and 18th centuries and its dialectal base] (PDF). Književni jezik (in Croatian). 19 (3): 109–120. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- Marić, Ante (2021). "Knjige za učenje hrvatskog jezika i profesori hrvatskog jezika u Odgojnom zavodu i Franjevačkoj klasičnoj gimnaziiji na Širokom Brijegu" [Books for learning the Croatian language and teachers of the Croatian language at the Educational Institute and the Franciscan Classical Gymnasium in Široki Brijeg]. Hrvatski: časopis za teoriju i praksu nastave hrvatskoga jezika, književnosti, govornoga i pismenoga izražavanja te medijske kulture (in Croatian). 19 (1): 43–58. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- Pavičić, Vlado (2008). "Fra Laurentius de Gliubuschi: Aleksandar(ović), Sitović ili Šitović?" [Fra Laurentius de Gliubuschi: Aleksandar(ović), Sitović or Šitović?]. Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru (in Croatian) (52): 193–211. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- 1682 births

- 1729 deaths

- People from Ljubuški

- Croatian former Sunni Muslims

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Sunni Islam

- Croatian Franciscans

- Franciscans of the Franciscan Province of Bosnia

- Franciscan writers

- Baroque writers

- Croatian Latinists

- Grammarians of Latin

- Croatian writers in Latin

- 18th-century writers in Latin

- Croatian male poets

- Croatian male writers

- Croat writers from Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bosnia and Herzegovina Roman Catholic theologians

- Croatian Roman Catholic theologians

- Franciscan theologians

- 18th-century Croatian Roman Catholic priests