Marjorie Wallace (charity executive)

This article may have been created or edited in return for undisclosed payments, a violation of Wikipedia's terms of use. It may require cleanup to comply with Wikipedia's content policies, particularly neutral point of view. (January 2022) |

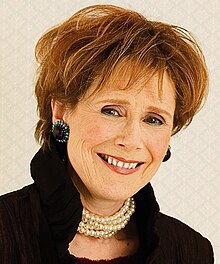

Marjorie Wallace | |

|---|---|

Marjorie Wallace | |

| Born | Marjorie Shiona Wallace 10 January 1943 |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University College London |

| Occupation | SANE Chief Executive |

| Spouse(s) | Andrzej Skarbek John Mills |

| Partner(s) | Tom Margerison Antony Armstrong-Jones, 1st Earl of Snowdon |

Marjorie Shiona Wallace CBE (born January 1943)[1] is a British investigative journalist, author, and broadcaster. She is the founder and chief executive of mental health charity SANE.[2][3][4][5][6]

Early life and education

[edit]Wallace was born in Nairobi, British Kenya, where her father was a civil engineer mapping the railways. Her mother was a classical pianist.[7]

After studying music, Wallace graduated with a degree in Psychology and Philosophy from University College London.[7][8]

Career

[edit]Journalism

[edit]Early career

[edit]After graduating, Wallace worked as a trainee producer for The Frost Programme with David Frost. She then became a religious programmes producer and a current affairs reporter for London Weekend Television.[9]

She later joined the BBC as a reporter and film director for news and current affairs programme Nationwide, including covering stories about homeless people and making the first film inside an IRA training camp.[10][11][9]

The Sunday Times

[edit]In 1972, Harold Evans, then editor of The Sunday Times, recruited Wallace into the Insight Team of the newspaper to work on the thalidomide scandal. She was tasked with tracking down as many of the cases where children had been born with deformities caused by the drug as possible.[12][13][14][9]

Wallace interviewed over 140 families affected by thalidomide, publishing weekly stories in the newspaper.[15] One of the cases was Terry Wiles, a child born with severe physical disabilities who had been adopted by Hazel and Len Wiles. The article is credited with helping to persuade Distillers, the company that distributed and marketed the drugs, to offer compensation to victims of the scandal.[16][12][15]

Wallace later turned Wiles’ story into a book and a screenplay, On Giant’s Shoulders, for a BBC television film broadcast in 1979 starring Judi Dench.[17] The drama won an International Emmy Award in 1980 and was also nominated for a BAFTA.[13][16][18] The Sunday Times expose of thalidomide led to victims being awarded over £28 million compensation.[12]

In 1976, Wallace reported on the Dioxin disaster in Seveso, northern Italy, which led to the publication of The Superpoison.[19]

In 1986, Wallace wrote a series of campaigning articles in The Times on schizophrenia and other severe mental illness. The articles were published under the title The Forgotten Illness. They focused on misconceptions about mental illness, the anguish and neglect of sufferers and families, and the failures of the community care policy.[20][21] The response to the articles was the largest The Times had ever received on a home news subject.[13]

SANE & mental health

[edit]In 1986, as a result of the scale of the public response to The Forgotten Illness articles, Marjorie Wallace founded SANE. The charity initially focused on the most severe mental illnesses, but it later expanded its remit to all mental health.[6][22]

Following the launch of the charity, Wallace recruited support for SANE from key figures in medicine, science, business, industry and the media, including Prince Charles as its first patron.[10][9] Minette Marrin in The Sunday Times wrote of Wallace: “She stands firmly and consciously in the tradition of 19th-century social reformers like Charles Dickens.”[2]

In 1992, Wallace founded SANEline, the UK's first national specialist out-of-hours mental health helpline, offering information and emotional support to individuals, families, carers, professionals, and the public.[23][9]

In 1994, Wallace also raised over £6 million to build a new research centre, The Prince of Wales International Centre for SANE Research, with donations from Xylas family, Prince Turki Al Faizal and The Sultan of Brunei.[9] The Centre promotes and hosts multidisciplinary teams researching and investigating the causes of psychosis. It was opened by Prince Charles in 2003.[24]

The Silent Twins

[edit]In 1982, Wallace met June and Jennifer Gibbons. Identical twins who had made a pact of silence to speak only with each other and no one else.[25] The twins were admitted to Broadmoor Hospital following a string of offences, including vandalism and arson. They remained at Broadmoor for 11 years, where Wallace earned their trust and publicised their cause.[26]

In 1986, Wallace published The Silent Twins. The book brought the twins to international attention, with Oliver Sacks writing that it was “a remarkable and tragic study in its depth, penetration and detail.” Wallace wrote the screenplay for the BBC film directed by Jon Amiel.[27][28][29]

The story was also turned into numerous plays, documentaries, and two operas.[26] Another film version of The Silent Twins, featuring Letitia Wright and Tamara Wilson, premiered at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival.[30]

Personal life

[edit]In 1974, Wallace married psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Andrzej Skarbek, with whom she had three children: Sacha, Stefan and Justin. The couple later separated, but did not divorce.[31][32]

Wallace was later the partner of Tom Margerison, founder of the New Scientist magazine and co-founder of London Weekend Television. Wallace and Margerison had one daughter together: Sophia. Margerison died in 2014.[33]

For over 40 years, Wallace was a close friend and confidante of Antony Armstrong-Jones, Earl of Snowdon. The couple campaigned together, writing articles for The Sunday Times about disadvantaged and disabled people, and were later romantically involved.[34][32]

In May 2021, Wallace married businessman, entrepreneur, and economist John Mills.[35]

Recognition

[edit]- 1982. Campaigning Journalist of the Year.[23]

- 1986. Campaigning Journalist of the Year.[23]

- 1988. The Snowdon Special Award.[36]

- 1989. Appointed Guardian Fellow at Nuffield College, University of Oxford.[9]

- 1994. Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).[37]

- 1997. Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.[6]

- 2002. British Neuroscience Association Award.[38]

- 2004. Appointed Fellow of University College London.[6]

- 2006. Recognised as one of the 16 key achievers who had made a difference in the health sector by the National Portrait Gallery.[39][40]

- 2008. Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE).[37]

- 2016. Outstanding Campaigner at the Women of the Year Awards for “advocating and raising greater awareness of mental health”.[41][42][43]

- 2019. Appointed an Honorary Member of The World Psychiatric Association.[44]

Selected filmography

[edit]- 1990. Whose Mind Is It Anyway? BBC One.[45]

- 1995. Circles of Madness. BBC.[46]

- 1997. In the Psychiatrist’s Chair. BBC Radio 4.[47]

- 2014. Inheritance Tracks. BBC Radio 4.[48]

- 2015. Desert Island Discs. BBC Radio 4.[7]

Selected bibliography

[edit]- 1976. On Giant’s Shoulders: The Story of Terry Wiles. Times Books.[16]

- 1978. Suffer the Children: The Story of Thalidomide. Viking Press.[49]

- 1979. The Superpoison. Macmillan.[19]

- 1986. The Silent Twins. Penguin.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ "Happy Birthday: Marjorie Wallace, 66". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ a b Marrin, Minette. "The woman who wouldn't take no for an answer". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Marjorie Wallace: 'All hell broke loose – I took a lot of flak for what I did'". www.telegraph.co.uk. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "This much I know: Marjorie Wallace". The Guardian. 5 February 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Marjorie Shiona WALLACE personal appointments - Find and update company information - GOV.UK". find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Marjorie Wallace CBE | SANE, mental illness charity". www.sane.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "BBC Radio 4 - Desert Island Discs, Marjorie Wallace". BBC. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "CBE for chief executive of Sane". 29 December 2007. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Marjorie Wallace, MBE - In conversation with Rosalind Ramsay" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Newsmaker: Voice of the forgotten - Marjorie Wallace, Chief executive, Sane". www.thirdsector.co.uk. 19 November 2003. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Honour for mental health campaigner Marjorie Wallace". PMLive. 7 July 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "How Harry Evans took up the long fight for thalidomide families". The Guardian. 26 September 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Butcher, James (14 July 2007). "Marjorie Wallace: campaigning for people with mental illness". The Lancet. 370 (9582): 127. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61073-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 17630024. S2CID 9738127.

- ^ Arbuthnot, Leaf. "Today, kids, we're off to Broadmoor". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b Kellner, Peter. "Prospect - The immense journalistic courage of Harry Evans".

- ^ a b c Wallace, Marjorie (1976). On giant's shoulders : the story of Terry Wiles. Michael Robson. London: Times Books. ISBN 0-7230-0146-4. OCLC 4593907.

- ^ "Broadcast - BBC Programme Index". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk. 4 November 1986. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Newland, Paul (2010). Don't Look Now: British Cinema in the 1970s. Intellect Books. ISBN 978-1-84150-320-2.

- ^ a b Margerison, Tom (1981). The superpoison 1976-1978. Marjorie Wallace, Dalbert Hallenstein. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-22797-2. OCLC 7703908.

- ^ McGennis, Aidan (September 1989). "The Forgotten Illness By Marjorie Wallace. Times Newspapers 1987. Available from SANE. (Schizophrenia: A National Emergency), 6th Floor, 120 Regent Street, London W1A 5EE. Stg.£1.00". Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine. 6 (2): 154. doi:10.1017/S0790966700015561. ISSN 0790-9667. S2CID 58136870.

- ^ Blake, Imogen (8 August 2014). "'I have taken on too much darkness': SANE founder Marjorie Wallace reveals impact of lifetime's work in mental health". Hampstead Highgate Express. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "About Us | SANE". www.sane.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Guardian Staff (16 March 2005). "Interview: Marjorie Wallace, founder of mental health charity Sane". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Prince of Wales International Centre for SANE Research, Tim Crow". www.sane.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "The Identical Twin Sisters Who Retreated Into Their Own World". The New Yorker. 27 November 2000. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b "The Silent Twins". NPR.org. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b Wallace, Marjorie (1996). The silent twins. London: Vintage. ISBN 0-09-958641-X. OCLC 60262552.

- ^ "Marjorie Wallace - The Silent Twins". www.sane.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Broadcast - BBC Programme Index". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk. 19 January 1986. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (8 April 2021). "Focus Features Acquires 'Silent Twins' With Letitia Wright & Tamara Lawrance". Deadline. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Youle, Emma (25 November 2011). "Tributes to Polish count and distinguished psychoanalyst who has died". Hampstead Highgate Express. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Charity founder honoured as Lord Snowdon affair is exposed". Hampstead Highgate Express. 13 June 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Tom Margerison obituary". The Guardian. 2 March 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Bloxham, Andy (5 June 2008). "Lord Snowdon's mistress Marjorie Wallace reveals five-year affair". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Langlois, André (31 May 2021). "Masquerade ball for Highgate wedding". Hampstead Highgate Express. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "The Big Interview: Marjorie Wallace, Founder of SANE - Part Two". Happiful Magazine. 2 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b "The Queen's high praise for pastor". Tottenham Independent. 3 January 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Marjorie Wallace". www.terrywiles.20m.com. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Marjorie Wallace (Countess Skarbek) - National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "A Picture of Health: Portraits by Julia Fullerton-Batten - National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Behrmann, Anna (17 October 2016). "Highgate charity campaigner honoured with 'Woman of the Year' award". Hampstead Highgate Express. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Toone, Lindsay. "Marjorie Wallace CBE - Women of the Year". www.womenoftheyear.co.uk/. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Marjorie Wallace named Outstanding Campaigner at the 2016 Women of the Year Awards". www.sane.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "SANE chief executive awarded honorary membership of the World Psychiatric Association". www.sane.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Broadcast - BBC Programme Index". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk. 5 April 1990. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Circles of Madness (1995)". BFI. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 Extra - In the Psychiatrist's Chair, Marjorie Wallace". BBC. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Inheritance Tracks, Marjorie Wallace". BBC. 8 February 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Suffer the children : the story of thalidomide. Sunday Times of London. New York: Viking Press. 1979. ISBN 0-670-68114-8. OCLC 4211068.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

[edit]- Minette Marrin, "The Woman Who Wouldn't Take No For An Answer" (interview), The Sunday Times, 8 July 2007

- Victoria Lambert, "Marjorie Wallace: 'All hell broke loose – I took a lot of flak for what I did'" (interview), The Telegraph, 10 July 2014

- Alex Clark, "This Much I Know: Marjorie Wallace" (interview), The Observer, 5 February 2012