Materialism controversy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The materialism controversy (German: Materialismusstreit) was a debate in the mid-19th century regarding the implications for current worldviews of the natural sciences. In the 1840s, a new type of materialism was developed, influenced by the methodological advancements in biology and the decline of idealistic philosophy. This form of materialism aimed to explain humans in scientific terms. The controversy revolved around whether the findings of natural sciences were compatible with the concepts of an immaterial soul, a personal God and free will. Additionally, the debate focused on the epistemological requirements of a materialist/mechanist worldview.[1]

In his "Physiologische Briefe" from 1846, the zoologist Carl Vogt explained that "thoughts have roughly the same relationship to the brain as bile has to the liver or urine to the kidneys."[2] In 1854, the physiologist Rudolf Wagner criticised Vogt's polemical commitment to materialism in a speech to the Göttingen Naturalists' Assembly. Wagner argued that Christian faith and natural history were two largely independent spheres. The natural sciences could therefore contribute nothing to the questions of the existence of God, the immaterial soul or free will.

One must not always let it go when this frivolous rabble wants to cheat the nation of the most precious goods inherited from our fathers and shamelessly blows the stinking breath from the fermenting contents of its bowels towards the people and wants to make them believe that it is a vain perfume.[3]

Wagner's attacks provoked equally sharp reactions from Vogt. The materialist point of view was also defended in the following years by the physiologist Jakob Moleschott and the doctor Ludwig Büchner, a brother of the well-known writer Georg Büchner. The materialists presented themselves as champions against philosophical, religious, and political reactionism. They set very different emphases[4] but could count on broad support among the bourgeoisie. The promise of a scientific worldview became a defining element of the cultural conflicts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Development of natural scientific materialism

[edit]Emancipation of biology

[edit]

The rise of popular materialism was encouraged by a critique of romantic-idealistic natural philosophy,[5] which became widespread after 1830 and had an equal influence on natural science, philosophy, and politics.

From the perspective of the history of science, the cell theory founded by Matthias Jacob Schleiden proved to be particularly influential. In his 1838 publication on phytogenesis, Schleiden declared the cell as the fundamental unit of all plants and identified the cell nucleus, which was discovered in 1831, as an essential factor in plant growth.[6] The cellular theory of plant organism structure brought about a reorientation in botany. Before this, botany was primarily focused on macroscopic descriptions of forms. Schleiden's theory of plant structure was combined with a methodological critique of idealistic natural philosophy. The cell theory is based on empirically verifiable observations. This is because "one only knows as many facts about the objects of the physical natural sciences as they have observed themselves". The speculations of natural philosophers, on the other hand, were not based on strict observation. Therefore, all "forging of systems and theories had to be thrown" aside.[7]

Schleiden's programme for a methodically renewed botany was extended to other biological disciplines in subsequent years. In 1839, Theodor Schwann published his Mikroskopische Untersuchungen über die Uebereinstimmung in der Struktur und dem Wachsthum der Thiere und Pflanzen. Schwann explained that the cell theory revealed the general principle of life. All living organisms are composed entirely of cells, and the formation of organs can be explained by the growth and reproduction of cells. Rudolf Virchow proclaimed in this context that "Life is essentially cellular activity".[8] The cell theory thus opened up the prospect of a scientific theory of life, on which materialists were able to build a few years later.

Turning away from idealistic philosophy

[edit]

Parallel to the methodological reorientation of the biological disciplines, a general criticism of the conservative legacy of German idealism developed in the intellectual climate of the Vormärz.[9] In the natural sciences, criticism of natural philosophical methodology remained moderate, with many biologists remaining staunch anti-materialists. On the other hand, it was only a few years after Hegel died in 1831, when philosophical movements emerged that radically broke with German idealism in terms of ideology.

The critique of religion, as presented by Ludwig Feuerbach in The Essence of Christianity, was socially explosive and of particular importance.[10] Feuerbach had attended every one of Hegel's lectures for over two years and wrote traditional idealist texts until the 1830s, having studied under Hegel in Berlin from 1824. However, Feuerbach and many other young students of Hegel began to have doubts. The young Hegelians were critical not only of the political conservatism of German idealism but also of the detached-from-empirical-observations philosophy of systems. In 1839, Feuerbach finally criticized his teacher's idealistic system in its principles. Although coherent and conclusive, it had distanced itself from sensory nature in an inadmissible way. Philosophy should be grounded in the sensual to arrive at a realization of nature and reality. "Vanity is therefore all speculation that seeks to go beyond nature and man."[11] Feuerbach and the new biological movements shared the idea of a view of nature emancipated from speculation. However, Feuerbach's goal was an anthropological theory of man, not one of the natural sciences.

Feuerbach's explosive anthropology revealed itself most in his philosophy of religion. Idealist philosophy had erred in attempting to prove the truth of the theological doctrines through abstract arguments. In reality, he argued, religion was not a metaphysical truth, but an expression of human needs. The existence of God could not be proven by theologians and philosophers, as God was a human invention. Feuerbach's argument was not directed against religions in general. He acknowledged that there were certainly good reasons for religious belief. But he believed that these reasons were of a psychological nature, as religions satisfied real human needs. In contrast, philosophical-theological proofs of the existence of God were seen as speculative fantasies. Feuerbach's critique of religion was received as a radical attack on the cultural establishment, and by the mid-1840s, he had become the centre of philosophical renewal movements.

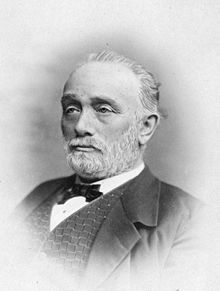

Carl Vogt and the political opposition

[edit]

The materialism controversy was sparked by the materialist theses published by physiologist Carl Vogt from 1847 onwards. Vogt's turn towards materialism was influenced by the scientific and cultural renewal movements, as well as his political development.[12] Vogt was born in Giessen in 1817 and grew up in a family that combined scientific and social revolutionary tendencies. Philipp Friedrich Wilhelm Vogt, Carl's father, was a medical professor in Giessen until he accepted a professorship in Bern in 1834 due to the threat of political persecution. The political entanglements were in the tradition of the family on his mother's side. Louise Follen's three brothers were all forced into emigration due to their nationalist and democratic activities.[13]

In 1817 Adolf Follen drafted an outline for a future imperial constitution. Two years later, he was arrested for "German activities". His subsequent exile in Switzerland spared him from a 10-year prison sentence. Karl Follen defended tyrannicide in a pamphlet and was therefore considered the intellectual author of the assassination attempt on the writer August von Kotzebue. He managed to escape to the United States, where he established himself as a professor of German at Harvard University from 1825. In 1833 Paul Follen, the youngest of the Follen brothers, co-founded the Gießener Auswanderungsgesellschaft with Friedrich Münch. Although the society's goal of establishing a German republic in the United States was unsuccessful, Paul Follen eventually settled in Missouri and became a farmer.

Carl Vogt started studying medicine at Giessen in 1833, but switched to chemistry under the guidance of Justus Liebig. Liebig's experimental methods were in direct contrast to the idealistic philosophy of nature. As a co-founder of organic chemistry, Liebig rejected the separation between living processes and dead matter, providing Vogt with an intellectual foundation for the materialism that he later developed.[14] However, in 1835, Vogt was unable to continue his studies in Giessen due to political circumstances. He had assisted a politically persecuted student to escape, which made him a target of the police. As a result, Vogt emigrated to Switzerland and completed his studies at the Faculty of Medicine in 1839.

During the early 1840s Vogt became involved with the political opposition and new scientific movements. However, he had not yet developed his ideological materialism at this point. It was during his three-year stay in Paris that Vogt's political and ideological radicalisation occurred. His acquaintance with anarchists Mikhail Bakunin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon had a lasting influence on Vogt's political thinking. Starting in 1845, he began publishing his Physiologische Briefe, which presented physiology clearly and understandably based on Liebig's Chemische Briefe.

The initial letters did not reference Vogt's materialism. Only in the letter on nerve power and mental activity, published in 1846, did Vogt state "that the seat of consciousness, will and thought must ultimately be sought solely in the brain".[15]

Initially, however, political practice took precedence over materialist theory. Vogt had just been appointed professor of zoology in Giessen, through the influence of Liebig and Alexander von Humboldt, when the German Revolution began in March 1848 and democratic forces rose up against the so-called reaction in various parts of Germany. When the March Revolution reached the small university town of Giessen, Vogt was appointed commander of the militia and eventually represented the 6th electoral district of Hesse-Darmstadt in the Frankfurt Parliament from 1848 to 1849. After the Prussian King Frederick William IV rejected the imperial dignity offered to him and political defeats led to the dissolution of the National Assembly, Vogt moved to Stuttgart with the remaining 158 deputies to form the so-called rump parliament, which was forcibly dissolved after only a few weeks in early June 1849.

Appointed as one of the "five imperial regents" by the remaining parliament, Vogt found himself at the centre of the political opposition. On 18 June of that year, Württemberg troops occupied the conference venue. Vogt emigrated to Switzerland and took refuge in his parents' house. Having failed in his political ambitions and deprived of his academic career, he once again focused on biological studies, which he now interpreted in a radically ideological way.

Progression of the debate

[edit]Materialism controversy until 1854

[edit]In 1850, Vogt travelled to Nice to pursue zoological studies due to a lack of clear academic prospects. The following year, he published a book on animal states that combined zoology with a critical evaluation of the German state of affairs. The book contained a political plea in favour of anarchism, arguing that "every form of government, every law [is] a sign of the lack of completion of our state of nature".[16] Vogt's biologistic argument in favour of anarchism was based on the idea that humans are natural and completely material organisms, in continuity with animal states. According to Vogt, biology implied both materialism and the subversion of the prevailing order. In his book, he referred unequivocally to the German situation:

So go forth, little book, as an old truth in a new guise. Pilgrim around in that wretched land whose language you speak, but whose mind will hardly meet you.[17]

Vogt succeeded in generating interest among the German public with his popular and polemical attacks. In 1852, he published Bilder aus dem Thierleben, which not only provided a detailed description of materialism but also strongly criticised German university scholars. It is argued that every biologist who thinks clearly must acknowledge the truth of materialism, as the dependence of soul functions on brain functions is evident. This dependence is most clearly shown in animal experiments, so "we can cut off the mental functions of the pigeon piece by piece by removing the brain piece by piece".[18] But if the soul's functions depended on the brain in this way, the soul could not survive the death of the body. And if the brain functions are determined by the laws of nature, then the same must also apply to the soul.

Thus the door would be opened to simple materialism – man, as well as the animal, would be only a machine, his thinking the result of a certain organisation – free will therefore abolished? [...] Truly, that is so. It really is so.[19]

According to Vogt, those who disagreed with these statements had not understood the necessary consequences of physiological research. This criticism was directed towards Rudolf Wagner, an anatomist and physiologist from Göttingen, who in 1851, had criticised Vogt in the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung for replacing God with a "blind, unconscious necessity".[20] Wagner had also suggested that the soul of a child is composed of equal parts of the mother's and father's souls. Vogt found this idea to be a useful model. The concept of a composite child's soul not only contradicts the theological belief in the indivisibility of the soul, but is also physiologically nonsensical. Physical characteristics, such as facial features, are naturally inherited from parents to their children, and the same applies to the brain. This is why the inheritance of character traits can be easily explained in materialistic terms.[21]

Göttingen Naturalists' Meeting

[edit]

During the summer of 1854, the 31st Naturalists' Meeting was held in Göttingen. The meeting was dominated by the debate over the existence of a God-created soul.[22] Wagner used this platform to deliver a lecture on human creation and the substance of the soul. In his lecture, he accused the materialists of undermining the moral foundations of social order by denying free will.

We who are gathered here, however different our world view may have been in each of us, we who have seen and felt the struggle of our nation in its last battles, and to a large extent have participated in it ourselves, we must also ask ourselves what the results of our research will be for the education and future of our great people.[23]

Vogt's materialism contradicted the moral responsibility of the researcher, as it reduced people to blind and irresponsible machines. In the same year, Wagner published a second paper in which he added to his moral criticisms with a general argument on the relationship between knowledge and faith. According to Wagner, these are two largely independent areas, meaning that no scientific knowledge can prove or disprove religious faith.

Physiologists describe the internal structure and function of physical organs. Materialists interpret these descriptions by identifying physical and mental functions. Dualists assume that bodily functions act on an immaterial soul. The natural sciences cannot decide the question of the soul, because neither interpretation could be derived from a physiological description. "There is not a single point in the biblical]doctrine of the soul [...] that would contradict any doctrine of modern physiology and natural science."[24]

Charcoal burning faith and science

[edit]Wagner's pamphlets brought the materialism debate to the centre of public interest. In response, Vogt wrote the polemic Köhlerglaube und Wissenschaft against Hofrath Rudolf Wagner in Göttingen. The first half of the text consists of ad hominem attacks against Wagner. It was alleged that he was not a serious and productive scientist, but merely adorned himself as the editor of countless works with the research work of others, and that he had also tried to suppress his materialistic critics with the help of state power. Wagner asserted that the materialist denial of free will was socially irresponsible in view of the political events of 1848 (March Revolution), in response to Vogt's anger.

Wretched wretch! Where did you take part, sympathise, participate on one side or the other? [...] We have not seen you, neither in the ranks of our enemies, nor in those of our friends, and we can call out to you with the poet: 'Fie on you boy behind the stove.[25]

In the second part of the work, Vogt systematically argued against Wagner's thesis of the compatibility of "naive Köhler faith" and scientific knowledge. Vogt stated that anyone who places the soul in a realm beyond empirical verifiability cannot be directly refuted by physiology. However, this assumption is ultimately useless and even incomprehensible. The relationship between soul and brain functions supports the idea of an identity between the body and soul, rather than confirming the axiom of the immaterial soul. This view is shared by Wagner, who acknowledges that all organs, except for the brain, are subject to biological processes. Wagner also does not propose the existence of a "muscle soul" that initiates muscle contraction. He does not argue that there is a kidney soul responsible for the excretion of metabolic products, in addition to the biological processes in the kidneys. "It is only in the case of the brain that this is not recognised; it is only in the case of the brain that a special, illogical conclusion that is not valid for the other organs is accepted".[26]

Food, strength and substance

[edit]By 1855 the commitment to materialism had become an influential movement, despite Vogt's polemical theses facing resistance in academic and political circles. Vogt was supported by two younger scientists, Jakob Moleschott and Ludwig Büchner, who also published their materialist ideas in popular science publications. These three authors were portrayed as champions of materialism, which appeared to be conclusive. The debate surrounding materialism catalyzed intensifying popularisation efforts and ideological debates, not themselves without controversy, about the relationship between natural science and society. This led to discussions about the Darwinian theory of evolution from the late 1850s onwards.[27]

Jakob Moleschott was born in 's-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands, in 1822. He came into contact with Hegel's philosophy at an early age but eventually studied medicine in Heidelberg.[28] Becoming strongly influenced by Feuerbach's philosophy, he focused on questions of metabolism and dietetics. Moleschott believed that food was the fundamental building block of both physical and mental functions, in line with his materialistic convictions. In his book 'Die Lehre der Nahrungsmittel: Für das Volk', Moleschott aimed to popularise his studies and presented detailed dietary plans for the impoverished sections of the population. The materialistic approach should not only deny the existence of an immaterial soul and God but also positively lead people to a better life.

In 1850 Moleschott sent a copy of his work to Feuerbach, who published an influential review titled Die Naturwissenschaft und die Revolution in the same year. In the 1840s, Feuerbach had defined his philosophy beyond idealism and materialism; now he explicitly supported the materialists. The philosophers continued to argue fruitlessly about the relationship between body and soul, while the natural sciences had already found the answer.

Food becomes blood, blood becomes heart and brain, thoughts and mind. Human food is the basis of human education and attitude. If you want to improve the people, give them better food instead of declamations against sin. Man is what he eats.[29]

Büchner's relationship with the public was even more influential than Moleschott's alliance with Feuerbach.[30] Born in Darmstadt in 1824, Büchner had already met Vogt as a student. In 1848, he became a member of the citizens' militia led by Vogt. After a few unhappy years as an assistant at the medical faculty in Tübingen, Büchner decided to publish a concise summary of the materialist worldview. Kraft und Stoff was a bestseller, with 12 editions published in the first 17 years, and translated into 16 languages. Unlike Vogt and Moleschott, Büchner presented materialism in a summary of findings that could be understood without prior philosophical or scientific knowledge, rather than in the context of his research. The starting point was the unity of force and substance, which Moleschott had already emphasised. Inherent forces are necessary for the existence of substance, just as substance is necessary as a carrier for forces. This unity directly implies the impossibility of immaterial souls, as they would have to exist without a material carrier.

Reactions in the 19th century

[edit]Philosophy of neo-Kantianism

[edit]Materialism was supported by natural scientists such as Vogt, Moleschott, and Büchner, who presented their theories as the consequences of empirical research. Following the collapse of German idealism, university philosophy appeared discredited as baseless speculation. Even the philosopher Feuerbach entrusted the natural sciences with resolving the philosophical question of the relationship between soul and body.

An influential philosophical critique of materialism did not develop until the 1860s with the emergence of Neo-Kantianism. In 1865, Otto Liebmann strongly criticised philosophical approaches from German idealism to Schopenhauer in his work Kant und die Epigonen, concluding each chapter with the statement "So we must go back to Kant!".[31] Friedrich Albert Lange published his Geschichte des Materialismus the following year, in agreement with this position. Lange accused the materialists of "philosophical dilettantism", which, according to Kantian philosophy, ignored essential insights.[32]

The Critique of Pure Reason's central theme was the question of the conditions of all possible knowledge, including scientific knowledge. Kant argued that human cognition does not depict the world as it really is. All knowledge is already characterized by categories such as "cause and effect" or "unity and multiplicity". These categories are not properties of the things themselves but are brought to the things by humans. Similarly, space and time lack absolute reality and are instead forms of human perception. As all knowledge is already characterised by categories and forms of perception, it is impossible for humans to recognise things in themselves. Therefore, it is not possible to scientifically prove or refute the existence of an immaterial soul, a personal God, or free will.

Lange argues that materialists made a fundamental error by disregarding Kant. Materialism posited that only matter exists, but failed to acknowledge that even scientific descriptions of matter do not describe absolute reality. Such descriptions already assume the categories and forms of perception, and therefore cannot be considered descriptions of things in themselves.[33] Lange's argument is supported by the natural scientist Hermann von Helmholtz, who presented his work on sensory physiology in the 1850s as an empirical confirmation of Kant's work. In his 1855 lecture Ueber das Sehen des Menschen (On Human Vision), Helmholtz first described the physiological foundations of visual perception and then explained that vision is not a true-to-life representation of the outside world. Following Kant's philosophy, it is argued that human interpretation characterises every perception of the outside world, making it impossible to access things in themselves.

But as it is with the eye, so it is with the other senses; we never perceive the objects of the outside world directly, but we only perceive the effects of these objects on our nervous system.[34]

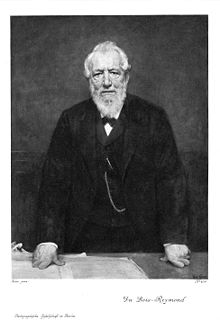

Ignoramus et ignorabimus

[edit]

The scientific materialists did not engage with the arguments of the Neo-Kantians, as they saw the reference to Kant as just another speculative attack on the results of the natural sciences. However, the criticism of physiologist Emil Heinrich Du Bois-Reymond in his 1872 lecture Ueber die Grenzen des Naturerkennens, which declared consciousness to be a fundamental limit of the natural sciences, appeared more concerning. His phrase "Ignoramus et ignorabimus" (Latin for "We do not know and we will never know") sparked a long-lasting controversy regarding the concept of a scientific worldview. This controversy, known as the Ignorabimus controversy, was debated with similar fervour to the Vogt and Wagner debate 20 years prior, and even more so in the political arena. However, this time the materialists were on the defensive.[35]

Du Bois-Reymond argued that the materialists' main problem was their inadequate argument in favour of the unity of brain and soul. Vogt, Moleschott, and Büchner only emphasized the dependence of soul functions on brain functions. Tests on animals had already demonstrated that damage to the brain leads to an impairment of mental functions. The concept of an immaterial soul is therefore rendered implausible by this dependency, making materialism the only acceptable conclusion. However, this consequence simply ignores the question of how the brain generates consciousness in the first place, how Büchner put it himself:

Incidentally, for the purpose of this investigation, it may seem quite indifferent whether and in what way it is possible to imagine how phenomena of the spirit arise from material connections or activities of the brain substance, or how material movement is transformed into a movement of the spirit. It is sufficient to know that material movements act on the spirit through the mediation of the sense organs.[36]

Du Bois-Reymond argued that proving dependency relationships was not enough to support materialism. To reduce consciousness to the brain, one must also explain it through brain functions. But the materialists were unable to provide such an explanation: "What conceivable connection is there between certain movements of certain atoms in my brain on the one hand, and on the other hand the original, undefinable, undeniable facts 'I feel pain, feel desire; I taste sweetness, smell the scent of roses, hear the sound of an organ, see red'."[37] Du Bois-Reymond argued that there is no conceivable connection between the objectively described facts of the physical world and the subjectively determined facts of conscious experience. Therefore, consciousness represented a fundamental barrier to perceiving nature.

Du Bois-Reymond's Ignorabimus speech highlighted a fundamental weakness of scientific materialism. Although Vogt, Moleschott, and Büchner claimed that consciousness was material, they also acknowledged that brain functions could not explain it. This problem contributed to the development of a scientific worldview that shifted from materialism to monism in the late 19th century. Ernst Haeckel, the most famous proponent of a "monistic worldview", shared the materialists' rejection of dualism, idealism, and the concept of an immortal soul.

Monism, on the other hand [...] recognises only one single substance in the universe, which is God and nature at the same time; body and spirit (or matter and energy) are inseparable for them.[38]

However, Haeckel's monism differs from materialism in that it does not recognise the primacy of matter. According to it, body and spirit are inseparable and equally fundamental aspects of a substance. This monism appears to circumvent du Bois-Reymond's problem. If matter and spirit are equally fundamental aspects of a substance, then spirit no longer needs to be explained by matter.

Büchner also viewed monism as the appropriate response to philosophical criticism of materialism. In a letter to Haeckel dated 1875, he wrote:

I [...] have therefore never used the term 'materialism', which evokes a completely one-sided idea, for my school of thought and only accepted it here and there later out of necessity because the general public knew no other word for the whole movement [...]. The term 'monism' that you suggest is very good in itself, but it is very doubtful whether it will be accepted by the general public.[39]

Political and ideological impact

[edit]Although the materialists gained popularity among the general public, they were not successful politically. Vogt, Moleschott, and Büchner lost their careers at German universities due to their advocacy of materialism. The revolutionary nature of Vogt's materialism could not succeed during the reactionary era after 1848. During the political movements of the latter half of the 19th century, scientific materialism failed to exert significant influence, partly due to differences with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marx labelled Vogt as a "small-university beer bouncer and misguided Barrot of the Reich",[40] and the conflicts escalated into personal denunciations. For instance, Marx's circle also accused Vogt of having worked as a French spy.[41]

The altered political situation is also apparent in the work of Ernst Haeckel, who embraced the concept of a scientific worldview from the materialists but gave it a fresh political orientation. Haeckel, who was 17 years younger than Vogt, established himself as a proponent of Darwinism in Germany during the 1860s. In his polemical rejection of "church-wisdom and [...] after-philosophy",[42] Haeckel closely resembled the scientific materialists. Vogt viewed physiology as the starting point for a scientific worldview, while Haeckel made a similar claim in referring to Charles Darwin:

In this spiritual battle, which now moves the whole of thinking humanity and which prepares a humane existence in the future, on the one side under the bright banner of science stand: freedom of thought and truth, reason and culture, development and progress; on the other side under the black banner of hierarchy: spiritual bondage and lies, irrationality and crudeness, superstition and regression.[43]

However, for Haeckel, the concept of "progress" was primarily anti-clerical, opposing the church rather than the state. Bismarck's Kulturkampf, which began in 1871, provided Haeckel with an opportunity to connect anti-clerical monism with Prussian politics. As the First World War approached, Haeckel's statements became increasingly nationalistic, with racial theories and eugenics providing a seemingly scientific basis for chauvinistic politics. Therefore, Vogt's vision of a politically revolutionary natural science ultimately proved itself short-lived.

Reception in the 20th century

[edit]In the 19th century, scientific materialism played a significant role in ideological debates. The discussions around Darwin's theory of evolution and Haeckel's monism gained prominence in the 1860s. Nonetheless, the question of a scientific worldview remained controversial, and Büchner's Kraft und Stoff remained a bestseller.

The First World War and Haeckel's death in 1919 were significant turning points. In the Weimar Republic, the debates of the 1850s were no longer relevant, and the philosophical currents of the interwar period consistently criticised materialism, despite differences in content. This also applied to logical positivism, which adhered to the idea of a scientific worldview but interpreted it in an anti-metaphysical way.[44] The logical positivists' criterion of meaning said that a proposition was only comprehensible if it could be verified empirically. This meant that materialism, monism, idealism, and dualism failed to meet this criterion and were considered misguided fantasies of a speculative era of philosophy. Materialist theories of consciousness were not revisited until the 1950s, when they were taken up from Anglo-Saxon philosophy. By this point, however, the scientific materialists of the 19th century had been forgotten. None of these new texts refer to Vogt, Moleschott or Büchner. Instead, the materialists of the post-war period focused on contemporary neuroscience.[45]

Scientific materialism was largely ignored in the history of science and philosophy until the 1970s.[46] Its reception in the GDR began relatively early under the influence of Dieter Wittich, who received his doctorate in 1960 with a thesis on the scientific materialists.[47] In 1971, he published a collection of texts entitled Vogt, Moleschott, Büchner: Schriften zum kleinbürgerlichen Materialismus in Deutschland with Akademie Verlag. In his detailed introduction, Wittich, who held the only chair for epistemology in the GDR, honoured the political, scientific, and religious-critical work of the materialists. However, he also pointed out their philosophical shortcomings. He stated that the "petty-bourgeois materialists" were "vulgar materialists because they insisted on metaphysical materialism at a time when dialectical materialism had become not only a possibility but also a reality".[48]

In 1977 Frederick Gregory, an American historian of science, published his monograph Scientific Materialism in Nineteenth Century Germany, which is still considered a standard work today. Gregory argues that the significance of Vogt, Moleschott and Büchner lies not in their specific elaboration of materialism, but rather in the social impact of their scientifically motivated criticism of religion, philosophy and politics. "The overwhelming trademark of the scientific materialists, as far as the historian is concerned, is not their materialism, but their atheism, more properly their humanistic religion."[49]

In line with Gregory's judgement, the significance of the materialists in the secularisation process of the 19th century is generally acknowledged in the current research literature, while their philosophical positions are still subject to fierce criticism in some cases. Renate Wahsner, for example, explains: "It is not possible to contradict the view held in the literature, which denies all three of them sharpness and depth of thought".[50] Not all authors share this negative assessment, with Kurt Bayertz, for example, defending the relevance of the scientific materialists, as they had developed "the first fully developed form of modern materialism". "Although the form of materialism developed by Vogt, Moleschott and Büchner is only one form of materialism, it is the form that is typical of modernity and the most influential and effective form today."[51] An examination of current materialism controversies must therefore begin in the 19th century.

References

[edit]- ^ Beiser (2014)

- ^ Vogt (1874, p. 323)

- ^ Wagner (1854b, p. IV)

- ^ Daum (2002, pp. 293–299)

- ^ Schnädelbach (1983, p. 100)

- ^ Schleiden, Matthias Jacob (1838). "Beiträge zur Phytogenesis". Archiv für Anatomie (in German). pp. 137–176.

- ^ Schleiden, quoted after Wittkau-Horgby (1998, p. 54f)

- ^ Virchow, Rudolf (1845). "Über das Bedürfnis und die Richtigkeit einer Medizin vom mechanischen Standpunkt". Virchows Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medizin (in German). Vol. 1 (published 1907). p. 8.

- ^ Jaeschke (1998)

- ^ See Gregory (1977a, pp. 13–28)

- ^ Feuerbach (1967, p. 52)

- ^ See Misteli (1938)

- ^ Hardtwig (1997, p. 13ff)

- ^ However, Liebig vehemently rejected materialism; see Brock (1999, p. 250)

- ^ Vogt (1874, p. 322)

- ^ Vogt (1851, p. 23)

- ^ Vogt (1851, p. IX)

- ^ Vogt (1852, p. 443)

- ^ Vogt (1852, p. 445)

- ^ Wagner cited following Daum (2002, p. 295)

- ^ Vogt (1874, p. 452f)

- ^ Diepgen, Goerke & Aschoff (1960, p. 35)

- ^ Wagner (1854a, p. 25)

- ^ Wagner (1854b, p. 30)

- ^ Vogt (1856, p. 10)

- ^ Vogt (1856, p. 111)

- ^ Daum (2002, pp. 294–307)

- ^ See Moleschott's autobiography, entitled Für meine Freunde. Lebenserinnerungen (1895), Gießen: Emil Roth.

- ^ Feuerbach, Ludwig (1967–2007). "Die Naturwissenschaft und die Revolution". Gesammelte Werke (in German) (X ed.). Berlin: Akademie Verlag. p. 22.

- ^ On Büchner, see "Büchner, Friedrich Karl Christian Ludwig (Louis) (1824–99)". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1998), London/ New York: Routledge, pp. 48–51.

- ^ Liebmann (1865)

- ^ Lange (1920, p. 31)

- ^ Lange (1920, p. 56)

- ^ Helmholtz (2003, p. 115)

- ^ Daum (2002, pp. 65–83)

- ^ Büchner (1932, p. 181)

- ^ Du Bois-Reymond (1974, p. 464)

- ^ Haeckel (1908, p. 13)

- ^ Büchner to Haeckel, 30 March 1875, in Knockerbeck (1999, p. 145)

- ^ Marx (1961, p. 463)

- ^ See Gregory (1977b)

- ^ Haeckel (1874, p. IX)

- ^ Haeckel (1874, p. XII)

- ^ For an overview see Heidelberger (2002)

- ^ See Place (1956) and Smart (1959)

- ^ Lübbe (1963) offers an exception.

- ^ Wittich, Dieter (1960). Der deutsche kleinbürgerliche Materialismus der Reaktionsjahre nach 1848/49 (in German). Dissertation. Berlin: Unpublished.

- ^ Wittich (1971, p. LXIV)

- ^ Gregory (1977a, p. 213)

- ^ Bayertz (2007, p. 73)

- ^ Bayertz (2007, p. 55)

Bibliography

[edit]Primary literature

[edit]- Beiser, Frederick C. (2014). After Hegel: German philosophy 1840-1900. Princeton, NJ Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17371-9.

- Büchner, Ludwig (1932). Kraft und Stoff (in German) (Pocket ed.). Leipzig: Kröner Verlag.

- Du Bois-Reymond, Emil; Wollgast, Siegfried (1974). Vorträge über Philosophie und Gesellschaft. Philosophische Bibliothek. Hamburg: F. Meiner. ISBN 978-3-7873-0320-5.

- Daum, Andreas W. (2002). Wissenschaftspopularisierung im 19. Jahrhundert. Bürgerliche Kultur, naturwissenschaftliche Bildung und die deutsche Öffentlichkeit 1848–1914 (in German) (2 ed.). Munich: Oldenbourg.

- Feuerbach, Ludwig (1967). Gesammelte Werke (in German). Vol. 3. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

- Haeckel, Ernst (1908). Die Welträthsel (in German). Leipzig: Kröner.

- Helmholtz, Hermann (2003). "Ueber das Sehen des Menschen". Gesammelte Schriften (in German). Vol. 1. Hildesheim: Olms.

- Lange, Friedrich Albert (1920) [1866]. Geschichte des Materialismus und Kritik seiner Bedeutung in der Gegenwart (in German). J. Baedeker.

- Marx, Karl (1961). Herr Vogt. Marx-Engels-Werke (in German). Vol. 14. Berlin: Dietz.

- Vogt, Carl (1856). Köhlerglaube und Wissenschaft. Eine Streitschrift gegen Hofrasth Rudolph Wagner in Göttingen (in German) (4th ed.). Gießen: Rickersche Buchhandlung.

- Vogt, Carl (1874). Physiologische Briefe (in German) (14 ed.). Gießen: Rickersche Buchhandlung.

- Wagner, Rudolf (1854a). Menschenschöpfung und Seelensubstanz. Ein anthropologischer Vortrag (in German). Göttingen: G.H. Wigand.

- Wagner, Rudolf (1854b). Ueber Wissen und Glauben. Mit besonderer Beziehung zur Zukunft der Seelen. Fortsetzung der Betrachtung über "Menschenschöpfung und Seelensubstanz" (in German). Göttingen: G.H. Wigand.

- Wittich, Dieter (1971). Vogt, Moleschott, Büchner. Schriften zum kleinbürgerlichen Materialismus in Deutschland (in German). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Secondary literature

[edit]- Bayertz, Kurt; Gerhard, Myriam; Jaeschke, Walter, eds. (2007). Der Materialismus-Streit. Weltanschauung, Philosophie und Naturwissenschaft im 19. Jahrhundert / hrsg. von Kurt Bayertz, Myriam Gerhard und Walter Jaeschke. Hamburg: Meiner. ISBN 978-3-7873-2010-3.

- Brock, Wilhelm (1999). Justus von Liebig (in German). Wiesbaden: Vieweg.

- Aschoff, Ludwig; Diepgen, P.; Goerke, H. (1960). Kurze Übersichtstabelle zur Geschichte der Medizin (in German). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-540-02498-9.

- Gregory, Frederick (1977a). Scientific materialism in nineteenth century Germany. Studies in the history of modern science. Dordrecht, Holland and Boston: D. Reidel Pub. Co. ISBN 978-90-277-0760-4.

- Gregory, Frederick (1977b). "Scientific versus Dialectical Materialism. A Clash of Ideologies in Nineteenth-Century German Radicalism". Isis. 68 (2): 206–223. doi:10.1086/351768.

- Haeckel, Ernst (1874). Anthropogenie (in German). Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

- Broszat, Martin; Hardtwig, Wolfgang, eds. (1997). Deutsche Geschichte der neuesten Zeit vom 19. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart. Vormärz: der monarchische Staat und das Bürgertum / Wolfgang Hardtwig. dtv (Orig.-Ausg., 4., aktualisierte Aufl ed.). Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar. ISBN 978-3-423-04502-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pauen, Michael; Stephan, Achim, eds. (2002). Phänomenales Bewusstsein: Rückkehr zur Identitätstheorie? (in German). Paderborn: Mentis. pp. 43–70. ISBN 978-3-89785-094-1. OCLC 53369599.

- Jaeschke, Walter (1998). Philosophie und Literatur im Vormärz. Der Streit um die Romantik (1820–1854) (in German). Hamburg: Meiner.

- Kockerbeck, Christoph, ed. (1999). Carl Vogt, Jacob Moleschott, Ludwig Büchner, Ernst Haeckel: Briefwechsel. Acta biohistorica. Marburg: Basilisken-Presse. ISBN 978-3-925347-50-4.

- Liebmann, Otto (1865). Kant und die Epigonen: eine kritische Abhandlung (in German). C. Schober.

- Lübbe, Hermann (1963). Politische Philosophie in Deutschland: Studien zu ihrer Geschichte (in German). B. Schwabe. ISBN 978-3-423-04154-6.

- Misteli, Hermann (1938). Carl Vogt : seine Entwicklung vom angehenden naturwissenschaftlichen Materialisten zum idealen Politiker der Paulskirche ; 1817 - 1849. Schweizer Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft. Zürich [u.a.] : Leemann.

- Place, Ullin (1956). "Is Consciousness a Brain Process?". British Journal of Psychology. 47 (1): 44–50.

- Schnädelbach, Herbert (1983). Philosophie in Deutschland 1831–1933 (in German). Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

- Smart, John J.C. (1959). "Sensations and Brain Processes". The Philosophical Review. 68 (2): 141–156.

- Vogt, Carl (1851). Untersuchungen über Thierstaaten (in German). Frankfurt a. M.: Literarische Anstalt.

- Vogt, Carl (1852). Bilder aus dem Thierleben (in German). Frankfurt a. M.: Literarische Anstalt.

- Wittkau-Horgby, Annette (1998). Materialismus: Entstehung und Wirkung in den Wissenschaften des 19. Jahrhunderts. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3525013752.

External links

[edit]- Digitised works of the scientific materialists in the Internet Archive

- Ernst Krause (1896), "Vogt, Carl", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 40, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 181–189

- Zeno. "Lexikoneintrag zu »Materialismus«. Eisler, Rudolf: Wörterbuch der philosophischen ..." www.zeno.org (in German). Retrieved 2024-04-11.

- Article on the materialism controversy in the German Medical Journal, 2006 (in German)