Meridian Hill Park

Meridian Hill Park | |

Cascading Waterfall, by sculptor John Joseph Earley, is a central feature of the park. | |

| Location | Bounded by 15th, 16th, Euclid, and W Streets NW Washington, D.C., U.S. |

|---|---|

| Area | 11.88 acres (4.81 ha) |

| Built | 1912-1936 |

| Architect | George Burnap Horace Peaslee |

| Architectural style | Italianate[1] |

| Part of | Meridian Hill Historic District (ID14000211) |

| NRHP reference No. | 74000273 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 25, 1974[2] |

| Designated NHL | April 19, 1994[2] |

| Designated DCIHS | November 8, 1964[2] |

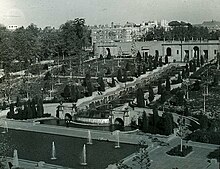

Meridian Hill Park is an urban park in Washington, D.C., located in the Meridian Hill neighborhood that straddles the border between Adams Morgan and Columbia Heights, in Northwest D.C. The park was built between 1912-40 and covers 11.88 acres (4.81 ha). Meridian Hill Park is bordered by 15th, 16th, W, and Euclid streets NW, and sits on a prominent hill 1.5 miles (2.4 km) directly north of the White House. Since 1969, the name Malcolm X Park is used by some in honor of Malcolm X.[3][4][5]

History

[edit]

At the time of Washington, D.C.'s creation in 1791, the land beneath present-day Meridian Hill Park was owned by Robert Peter, wealthy Georgetown merchant, and was known as Peter's Hill. In 1804, president Thomas Jefferson had a geodetic marker placed on this large hill. Centered exactly north of the White House, this marker helped to establish a longitudinal meridian for the city and the nation: the "White House meridian". After the War of 1812, David Porter, a commodore and naval hero of that war, acquired the hill in 1816 as part of a 110-acre (450,000 m2) tract of land that he had purchased; he named this property Meridian Hill. On the brow of this prominent hill on his new estate, and close to the marker, Porter then built a large and famous mansion which he also named Meridian Hill.[6] The home faced south with a dramatic view of the White House and the Potomac River. Meridian Hill Park today shares this view. Following his presidential term, John Quincy Adams briefly lived at Meridian Hill.

After the onset of the American Civil War, and with a strategic location overlooking the city, the Meridian Hill estate and mansion, along with the land of neighboring Columbian College (founded 1821, later moving and becoming George Washington University), were taken for use as an army encampment named Camp Cameron. At times, this location was referred to as being "on Georgetown Heights".[7][8][9]

Shortly after the war, a fire badly damaged the mansion, and the home ultimately was razed. At that time, Washington was experiencing postwar growth and some prosperity, so in 1867 the old Porter estate's land was subdivided into smaller lots. In 1887, former senator John Brooks Henderson and his wife Mary Foote Henderson, a wealthy couple from Missouri, resettled in Washington and purchased a large number of these real estate lots. On the west side of newly extended 16th Street, the Hendersons then built an elaborate stone home, designed to resemble a castle, which became known as Henderson Castle.

Mary, with many friends in Congress, had grand plans for the area and for the public use of the hill. She put forward, without success, two ambitious proposals, one by architect Paul J. Pelz in 1898 and the second by Franklin W. Smith in 1900, both with designs to construct a colossal presidential mansion on Meridian Hill to replace the White House. She next unsuccessfully proposed that the site be used for the planned Lincoln Memorial.

Early 20th century

[edit]When these did not work out, Mary Henderson focused on a park. In addition, with her own money and with architect George Oakley Totten Jr., she planned and then built her own projects, which included creating a succession of large, elaborate embassies and mansions along both 15th and 16th streets. These formal, well-made structures today frame Meridian Hill Park and help to create a thematic visual appearance to the area immediately around the park.

In 1901, the Senate Park Commission (with its McMillan Plan) undertook a set of formal changes to Washington's civic appearance, most famously by reconfiguring the city's National Mall. The commission also decided, with Mary's input, that a park on Meridian Hill was appropriate, and proceeded to plan for its creation. Mary, strong-willed, intelligent, vigorous and well-connected, very much championed the park. Later, throughout the many years of park construction, she lobbied Congress to maintain the flow of funding necessary to complete the project.

By an Act of Congress on June 25, 1910, Meridian Hill Park was established.[10] The federal government also purchased the land for the park in 1910, and began planning for its construction in 1912, with the Interior Department hiring landscape architect George Burnap to design a grand urban park modeled on parks found in European capitals. His plans were approved in early 1914, and later were modified by Horace Peaslee, who took over as project architect; the design included an Italian Renaissance-style terraced fountain cascade with pools in the lower half, and gardens in a French Baroque style in the upper half. The upper portion later was simplified somewhat to focus on an open mall, suitable for gatherings and performances. The well-designed and carefully made walls, fountains, balustrades and benches were built with concrete aggregate, a then-new type of building material consisting of a specially washed and exposed-pebble surface set into the concrete substrate. This construction technique for the park was created by master craftsman John Joseph Earley; he and his team of skilled artisans worked for years on the project.

The park plan conceived by Burnap and Peaslee was one composed to depict a formal Italian garden. The actual planting scheme was designed by New York landscape architects Vitale, Brinckerhoff, and Geiffert. In the past, gardens of this scope generally were reserved for aristocrats, but Meridian Hill Park, a product of democracy, was made for all people.[11] The many walls and stairways of the site's composition added variety to the park, and because the central structure is on a hillside, some of the stairways are rather dramatic. The park also contains well-designed textured-concrete benches and urns, and patterned-concrete walkways. After two decades under construction, the grounds were declared essentially complete, given park status, and then dedicated in 1936. Following its completion, the park became popular with city residents.

Late 20th century

[edit]

The upper mall area was often used for concerts and gatherings. At a political rally in 1969, activist Angela Davis proposed renaming the park Malcolm X Park, but ultimately this name change was not approved.[3] Locals continued to call the park Malcolm X Park in honour of the assassinated civil rights minister. In 2023 after the lower plaza renovation (to make park wheelchair accessible) was complete and the lower plaza reopened,[12] NPS for the first time acknowledged the park's local name: Malcolm X Park.[13][14][15]

After 1970, with inner-city areas of Washington experiencing an economic decline, the park and its neighborhood suffered some decay for a number of years, with crime and vandalism becoming a problem. Upkeep of the park suffered, and the park became less safe, with drug dealing at times occurring. About 1990, in response to rising crime rates in and around the park, neighborhood residents became more involved in the park's stewardship and programming, and a group of community organizations formed the Friends of Meridian Hill. This organization organized volunteer nighttime patrols to combat crime, planted trees, produced a wide range of community arts and educational programs in the park, including twilight concerts, and helped the National Park Service to make improvements to the park.

Contemporary

[edit]

In 1994, in recognition of the impact of the Friends of Meridian Hill, president Bill Clinton presented the Friends of Meridian Hill with the Partnership Leadership Award in a White House ceremony.[16] Since 2005, the Park Service has been working on a general restoration, carefully repairing and replacing the unique concrete structures as necessary, and replacing key utility systems. This ongoing work on the site continues today, and has resulted in a renovated asset for the city.

In 1994 the park was designated a National Historic Landmark, as "an outstanding accomplishment of early 20th century Neoclassicist park design in the United States",[17] and is today maintained as a part of Rock Creek Park.[18] In 2014 the District of Columbia government approved creation of the Meridian Hill Historic District in the local neighborhood around the park, with the park itself in the center of the newly designated area.

The park is now a place that is well-used and enjoyed by local residents. On Sunday afternoons during warm weather, people gather from 3 to 9 p.m. in the upper park to dance and participate in a drum circle. This activity, held in the park since the 1950s, regularly attracts both enthusiastic dancers and professional drummers.[19][20]

Geography

[edit]Meridian Hill Park measures 11.88 acres (4.81 ha) and is bordered by 15th Street NW on the east, 16th Street NW on the west, Euclid Street NW on the north, and W Street NW on the south.[21][1] It is located on elevated land in the small Meridian Hill neighborhood which straddles Adams Morgan and Columbia Heights.[22]: 1 The White House is sited 1.5 miles (2.4 km) directly south of the park, below the terminus of 16th Street NW. The park is divided into two sections, the upper (north) portion, and the lower (south) portion. The park's elevation decreases from north to south, approximately 75 feet (23 m) from its northern border on Euclid Street NW to its southern border on W Street NW.[1]: 5–6

The park faces south, originally providing sweeping views of the city. Its rectangular design features a central axis and cross axis which are then divided into asymmetrical portions.[1]: 11 The lower level of the park is wider, leading to the axis and overall design facing slightly southeast.[23]: 7 The upper and lower levels are divided by a large retaining wall.[23]: 4 The upper level features an open lawn flanked by sidewalks and trees, and a large terrace overlooking the lower level. The sidewalks on either side of the lawn were originally named Monument Vista Walk (east) and Concert Promenade (west). A winding pathway is located on the opposite sides of the trees, near the park's eastern and western borders.[1]: 5 [23]: 7 The lower level features a reflecting pool, plaza, and a cascade fountain flanked by stairways.[1]: 5 In addition to these stairways, there is a stairway on the western edge of the park and a winding path on its eastern edge.[23]: 8

Public artwork

[edit]A central feature of Meridian Hill Park is the 13-basin Cascading Waterfall which was inspired by 16th-century Italian villas. Located in the park's lower level, the concrete fountain was designed with a recirculating water system featuring an elaborate series of pumps. Water from two fountains on the terrace flows down to three columns and two spills located in a retaining wall. From there the water flows into two basins and spouts and overflows into thirteen cascading basins. The length of the basins increases as water flows down to a pool at the bottom of the waterfall. The pool features waterspouts depicting grotesque masks, water flowing from two dolphin carvings, and multiple jets.[23]: 26 [24]

There are five statues and memorials in the park. The first one, Dante Alighieri, was installed in 1921 and depicts Italian poet and philosopher Dante Alighieri, considered one of the greatest literary figures of the Late Middle Ages.[25]: 416 He is one of Italy's national poets, the "father" of the Italian language, and his work Divina Commedia (Divine Comedy) is one of the greatest pieces of Italian literary work.[26][27][28] The statue, by artist Ettore Ximenes, was a gift of Italian American businessman Carlo Barsotti, founder of Il Progresso Italo-Americano.[29][30] It is a cast of the statue in New York City's Dante Park which was also installed in 1921.[31] The statue in Meridian Hill Park was dedicated on December 1, 1921.[31] Among those in attendance at the ceremony were President Warren G. Harding and First Lady Florence Harding, Italian and French diplomats, and hundreds of Italian Americans.[29] The statue is located east of the Cascading Waterfall, in an area nicknamed the Poet's Corner.[23]: 32 [32]: 35

The second statue installed in the park was Joan of Arc, the only equestrian statue in Washington, D.C., depicting a woman.[33] Joan of Arc was a French heroine and patron saint who successfully led troops during the siege of Orléans. She was later put on trial for heresy and burned at the stake around the age of nineteen.[25]: 418 She became a national symbol of France beginning in the 1800s and was canonized by Pope Benedict XV in 1920.[34][35] A proposal to install a statue of Joan of Arc was initiated in 1916 by Carlo Polifeme, president of the Society of Women of France of New York (Société des Femmes de France de New York).[36] Several years later, a cast of the equestrian statue by artist Paul Dubois was completed.[25]: 418 The base was designed by McKim, Mead & White.[37] The statue was dedicated on January 6, 1922, a few weeks after the Dante Alighieri ceremony.[31] Harding and his wife also attended the event, along with Secretary of War John W. Weeks, Anne Rogers Minor, president of the Daughters of the American Revolution, numerous diplomats, and members of French American societies.[38] The sword Joan of Arc holds has been stolen and replaced many times.[39] The statue is located in the center of the grand terrace, overlooking the park's lower level.[23]: 32

Serenity, an allegorical sculpture by Spanish-Catalan artist Josep Clarà, was commissioned by American businessman and art dealer Charles Deering.[25]: 419 [40] He dedicated it to his lifelong friend, Lieutenant Commander William H. Schuetze, who traveled to Siberia to search for survivors of the ill-fated Jeannette expedition and later served in the White Squadron and as a navigator on the USS Iowa during the Spanish–American War.[25]: 419 [41] Installation of the sculpture in Meridian Hill Park was completed in July 1925.[42] Schuetze's name, carved into the granite base, is misspelled.[32]: 42 Due to a long history of repeated damage inflicted upon Serenity, the sculpture has been described as the "most vandalized memorial" in Washington, D.C.[43] The sculpture is located along a pathway in the northwest portion of the park and is partially obscured by trees.[23]: 33 [44]

The James Buchanan Memorial, which honors President James Buchanan, was in the original plans of the park.[23]: 20 It was sculpted by German American artist Hans Schuler.[45] Harriet Lane, Buchanan's niece who served as first lady during his presidential term since he was a bachelor, bequeathed $100,000 for a memorial to be erected in Washington, D.C., in honor of her uncle.[32]: 42 [46] Due to delays on preparing the park's lower level in the 1920s, the memorial was not dedicated until June 26, 1930.[23]: 20 [47] Attendees at the ceremony included President Herbert Hoover, Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, and Secretary of War Dwight F. Davis.[48] Extending on each side of Buchanan's statue is a stone exedra. At each end of the exedra is a concrete sculpture, one representing Law and the other Democracy. It is located on the southeast corner of the park, near the reflecting pool.[45]

The Noyes Armillary Sphere is an armillary sphere by artist C. Paul Jennewein. Funding for the sculpture was provided by artist Bertha Noyes, who donated $15,000 toward the project's cost in honor of her deceased sister, Edith. The design was inspired by Paul Manship's Cochran Armillary located on the campus of Phillips Academy in Massachusetts.[49]: 2 [50] It was installed in 1935, but work was not completed until the following year.[51][52][53] A bronze calibration plaque, located on a cast iron post by the sphere, was later installed to correct errors with time precision.[49]: 1 Decorative armillary spheres were added on top of the wrought-iron fence located on the north end of the park.[23]: 34 Due to damage, the sphere was removed in 1973 and placed into storage for repairs.[49]: 1 Some point after that it was either lost or stolen.[50] Using original drawings and photographs of the sphere, Kreilick Conservation LLC created a replica, which was installed in 2024.[54][55] It is located south of the reflecting pool.[23]: 33

-

Dante Alighieri (1921)

-

Joan of Arc (1922)

-

Serenity (1925)

-

James Buchanan Memorial (1930)

-

Noyes Armillary Sphere (1936)

Notes

[edit]- ^ The historic landmark designation form can be found at the bottom of the linked page in pdf format.

See also

[edit]- List of National Historic Landmarks in Washington, D.C.

- National Register of Historic Places listings in the upper NW Quadrant of Washington, D.C.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Carr, Ethan (October 13, 1993). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Meridian Hill Park". National Park Service. Retrieved March 3, 2025.

- ^ a b c "District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites" (PDF). District of Columbia Office of Planning. September 30, 2009. p. 98. Retrieved March 3, 2025.

- ^ a b Cultural Tourism DC (2005), Roads to Diversity: Adams Morgan Heritage Trail, archived from the original on 2016-03-13

- ^ "Washington: 10 things to do: Malcolm X Park", Time

- ^ Is it Meridian Hill Park or Malcolm X park? Your answer is Meaningful, 2018

- ^ Meridian Hill: A History, by Stephen McKevitt (History Press, 2014), p. 22.

- ^ The Blue and Gray in Black and White by Bob Zeller (Praeger Publishers, 2005), p. 50.

- ^ "Harper's Weekly illustrations". Sonofthesouth.net. 2007-01-26. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ "Harper's Weekly brief report". Sonofthesouth.net. 2007-01-26. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ U.S. Statutes-At-Large, 676 Stat. 36

- ^ "History & Culture – Meridian Hill Park". Archived from the original on 2013-01-18. Retrieved 2013-01-16. National Park Service – Meridian Hill Park History and Culture

- ^ ""Lower Meridian Hill/Malcolm X Park is finally open again" "With a New Entrance for the Physically Impaired" - PoPville". 6 February 2023.

- ^ In time for spring, lower plaza of Meridian Hill Park is open and more accessibleFebruary28,2023 https://www.nps.gov/rocr/learn/news/in-time-for-spring-lower-plaza-of-meridian-hill-park-is-open-and-more-accessible.htm

- ^ "Meridian Hill Park in DC reopens with new accessible route after 2-year rehab". 28 February 2023.

- ^ ""Meridian Hill Park, also known as Malcolm X Park, lower plaza level has reopened. The NPS is making plans to repair the cascading fountain" - PoPville". 2 March 2023.

- ^ The Great Neighborhood Book: A Do-it-Yourself Guide to Placemaking, by Jay Walljasper, p. 79.

- ^ "Meridian Hill Park". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2011-04-04. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ^ "Meridian Hill Park – Places (U.S. National Park Service)". Archived from the original on 2010-07-12. Retrieved 2010-12-17. National Park Service – Meridian Hill Park Points of Interest – North to South

- ^ "Meridian Hill Park: Sports and Recreation Locations in Washington, DC on washingtonpost.com's City Guide". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ "Meridian Hill/Malcolm X Park sur Flickr : partage de photos !". Flickr.com. 2006-04-23. Archived from the original on 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Dillon, Helen (October 5, 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form - Meridian Hill Park". National Park Service. p. 2. Retrieved March 3, 2025.

- ^ Elder, Elise (September 2019). "Meridian Hill Park - African American Experiences Since the Civil War: A Special Resource Study" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 3, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Historic American Buildings Survey: Meridian Hill Park" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 3, 2025.

- ^ "Cascading Waterfall, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Retrieved March 3, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Goode, James M. (1974). The Outdoor Sculpture of Washington, D.C. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 0-87474-149-1.

- ^ Matheson, Lister M. (2012). Icons of the Middle Ages: Rulers, Writers, Rebels, and Saints. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 244. ISBN 9781573567800.

- ^ Barański, Zygmunt G.; Gilson, Simon (2018). The Cambridge Companion to Dante's 'Commedia'. Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 9781108421294.

- ^ Shaw, Prue (2014). Reading Dante: From Here to Eternity. Liveright. pp. XIII. ISBN 9780871407801.

- ^ a b Brigham, Gertrude R. (1922). "The New Memorial to Dante in Washington". Art and Archaeology. 13 (1–6): 32–35.

- ^ "Italians to Unveil Statue Tomorrow". The Evening Star. November 30, 1921. p. 17. Retrieved March 4, 2025.

- ^ a b c DeFerrari, John; Sefton, Douglas Peter (2022). Sixteenth Street NW: Washington, DC's Avenue of Ambitions. Georgetown University Press. p. 108. ISBN 9781647121563.

- ^ a b c Clem, Fiona J. (2017). Meridian Hill Park. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781467125307.

- ^ "Joan of Arc Statue". National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 9, 2025. Retrieved February 24, 2025.

- ^ Boucheron, Patrick (2019). France in the World: A New Global History. Other Press. p. 251. ISBN 9781590519424.

- ^ Gies, Frances (1981). Joan of Arc: The Legend and the Reality. Harper & Row. p. 236. ISBN 9780690019421.

- ^ Brigham, Gertrude Richardson (1922). "A New Memorial to Jeanne D'Arc in Washington". Art and Archaeology. 13: 96.

- ^ "Joan of Arc, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Retrieved February 24, 2025.

- ^ Eliot, Jean (January 6, 1922). "Society". The Washington Times. p. 11. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2025.

- ^ Cartagena, Rosa (November 30, 2016). "People Have Been Stealing the Sword From This Joan of Arc Statue for Over 80 Years". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on 24 November 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2025.

- ^ "Serenity, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved February 15, 2025.

- ^ Mirabent, Isabel Coll (2012). Charles Deering and Ramón Casas / Charles Deering Y Ramón Casas: A Friendship in Art / Una Amistad en El Arte. Northwestern University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-8101-2843-9.

- ^ Annual Report of the Director of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital. United States Government Printing Office. 1926. pp. 45–46.

- ^ Valerio, Mike (March 25, 2017). "The 'most vandalized' memorial in Washington". WKYC. Retrieved February 15, 2025.

- ^ Kanter, Beth (2018). No Access Washington, DC: The Capital's Hidden Treasures, Haunts, and Forgotten Places. Globe Pequot Press. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-4930-3225-9.

- ^ a b "Buchanan, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Monuments and Memorials". The Evening Star. Washington, D.C. January 1, 1936. p. 12. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Hoover to Make Unveiling Speech". The Evening Star. Washington, D.C. June 18, 1930. p. A-5. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Hoover Dedicates Buchanan Statue". The New York Times. June 27, 1930. p. 17. ProQuest 98900401. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c O'Day, James (July 11, 2016). "Historic American Landscapes Survey: Meridian Hill Park, Noyes Armillary Sphere" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ a b Kelly, John (June 14, 2013). "Where, oh where is Meridian Hill Park's armillary sphere?". The Washington Post. ProQuest 1367634195. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ "Armillary Sphere Soon Will Be Installed". The Evening Star. February 12, 1935. pp. B-9. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ Mechlin, Leila (December 15, 1935). "Twin Exhibits of Work By Modernists To Be Shown". The Evening Star. pp. F-5. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ "Park Sundial Finished". The Evening Star. November 10, 1936. pp. A-4. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ "Resurrecting the Noyes Armillary Sphere". Kreilick Conservation LLC. December 2024. Archived from the original on January 15, 2025. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- ^ "Meridian Hill Park has a new armillary sphere". National Park Service. November 12, 2024. Archived from the original on January 14, 2025. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

External links

[edit]- National Park Service

- Meridian Hill Park, NRHP 'travel itinerary' listing at the National Park Service

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. DC-532, "Meridian Hill Park, Bounded by Fifteenth, Sixteenth, Euclid & W Streets, Northwest, Washington, District of Columbia, DC", 51 photos, 5 color transparencies, 25 measured drawings, 69 data pages, 5 photo caption pages

- Washington Parks and People

- Meridian Hill Neighborhood Association

- NPR: Why Urban Joes and CEOs Bang the Drum

- The Wild Man At The Center Of The World

- Historic district contributing properties

- 1912 establishments in Washington, D.C.

- District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Washington, D.C.

- Italian gardens

- Italianate architecture in Washington, D.C.

- Memorials to Malcolm X

- Meridian Hill/Malcolm X Park

- National Historic Landmarks in Washington, D.C.

- National Park Service areas in Washington, D.C.

- Parks in Washington, D.C.

- Rock Creek Park