Misshitsu

| Misshitsu | |

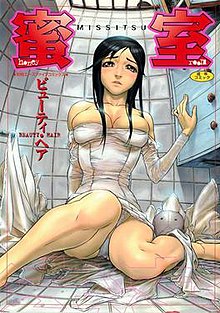

The cover of Misshitsu | |

| 蜜室 | |

|---|---|

| Manga | |

| Written by | Yūji Suwa (Beauty Hair) |

| Published by | Shōbunkan |

| Published | May 2002 |

Misshitsu (蜜室, lit. "Honey Room") is a hentai manga anthology written and illustrated by Yūji Suwa under the pen name Beauty Hair (ビューティ・ヘア, Byūti Hea) and published by Shōbunkan in May 2002. In 2004, the anthology became the subject of the first manga-related obscenity trial in Japan, in which Suwa and his publishers Kōichi Takada and Motonori Kishi were found guilty of violating Article 175 of the Japanese Criminal Code, which restricts the sale and distribution of pornography. In 2007, the ruling was upheld by Supreme Court of Japan.

Obscenity controversy

[edit]Misshitsu is a 144-page paperback hentai manga anthology published in May 2002 by Shōbunkan, a midsize erotic manga publisher founded in 1993 by Motonori Kishi. The collection exclusively consists of eight manga by Yūji Suwa, who authored the works under the pen name Beauty Hair (ビューティ・ヘア, Byūti Hea). "Mutual Love" (相思相愛, Sōshi Sōai), the manga that would become the primary subject of the obscenity indictments, originally appeared in the August 2001 edition of Shōbunkan's monthly magazine Himedorobō, which had a circulation of approximately 45,000. It later reappeared in Misshitsu, which sold 20,544 copies, and finally the August 2002 anthology, Himedorobō Best Collection, which sold approximately 15,000 copies.[1]

In August 2002, a father in Tokyo's 17th district found a copy of Himedorobō Best Collection in his teenage son's room. He sent an angry letter to his representative in the National Diet, Katsuei Hirasawa, singling out "Mutual Love" by Beauty Hair as the most offensive. The manga tells the story of a sex worker who seemingly suffers through the sadistic sexual desires of a client, including repeated whippings of her face and body with a belt and several instances of vaginal stomping. Despite this extreme physical abuse, she confesses her pleasure in the acts on the final page of the story. In "Crawling About" (這いずり回って, Haizurimawatte), another manga cited as objectionable by the prosecutor, a naïve girl sneaks out for a "date" that results in her being kidnapped, tortured (with cigarette burns and a brutal beating), and gang-raped. Hirasawa forwarded the father's letter to Tokyo police in mid-August, who conducted an investigation in which they compared Himedorobō Best Collection to three other Shōbunkan anthologies, including Misshitsu. According to the police, Misshitsu was targeted for prosecution based on their assessment that its "genitalia and scenes of sexual intercourse ... are drawn in detail and realistically", whereas the other works "were not sufficiently plain or detailed and were lacking in reality". Furthermore, they determined that the self-censorship markings used in Misshitsu, white or gray rectangular and triangular marks meant to obscure genitalia and penetration, were less conservative than those used in other works.[2]

On October 1, police arrested Suwa, Kishi, and editor-in-chief Kōichi Takada on charges of distributing obscene materials in violation Article 175 of the Criminal Code of Japan. To avoid jail time, Suwa and Takada pled guilty, being fined ¥500,000 each (approximately US$4,700); Kishi chose to stand as a defendant. On January 13, 2004, the lower court sentenced Kishi to a one-year prison term, suspended for three years.[3][4] He appealed to the Tokyo High Court, which on June 16, 2005, reduced his sentence to a fine of 1.5 million yen (approximately $13,750).[5] Kishi further appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan, which dismissed his appeal on June 14, 2007.[1]

Like in previous Japanese obscenity trials, arguments in the Misshitsu case centered around whether the work was considered "obscene" under Article 175. Citing the 1957 ruling of the Supreme Court of Japan in the so-called Chatterley Case, the lower court defined an obscene work as one that "arouses and stimulates sexual desire, offends a common sense of modesty or shame, and violates proper concepts of sexual morality." The defense challenged the conditions, submitting volumes of Edo-period shunga as evidence of comparably explicit yet artistically accepted works. In doing so, it sought to distance manga from the "mimetic" mediums of photography and film, portraying it instead as an "artistic" medium protected under the guarantee of freedom of expression in Article 21 of the Constitution of Japan. The court rejected this argument, arguing Misshitsu lacked the historical and cultural value of shunga. In its ruling, it further stated that manga as a medium had the potential to be more obscene than prose or drawings alone, with "characters' exclamations, onomatopoeia, and mimetic sounds ... imparting the whole with a sense of presence and increased sexual stimulus."[1]

In the wake of the trial, a number of retail bookstores and chains in Japan removed their adults-only section; their motivation has been attributed to the "chilling effect" of the verdict.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Cather, Kirsten (2012). The Art of Censorship in Postwar Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0824835873.

- ^ Galbraith, Patrick W. (2014). "The Misshitsu Trial: Thinking Obscenity with Japanese Comics". International Journal of Comic Art. 16 (1).

- ^ "Japanese manga ruled obscene". British Broadcasting Corporation. 13 January 2004. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Joyce, Colin (14 January 2004). "Comics can be pornographic, rules Japanese judge". The Telegraph. Tokyo. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Erotic manga publisher to take case to Supreme Court". Japan Today. 9 August 2005. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Gravett, Paul (23 April 2006). "Manga: An Introduction". Retrieved 23 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Full scan of Misshitsu, as archived by the Internet Archive (in Japanese)