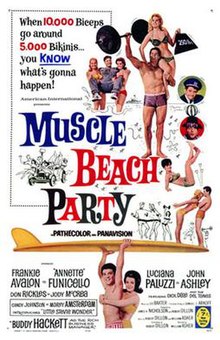

Muscle Beach Party

| Muscle Beach Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | William Asher |

| Screenplay by | Robert Dillon |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Harold E. Wellman |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Les Baxter |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[1] or $150,000[2] |

Muscle Beach Party is the second of seven beach party films produced by American International Pictures. It stars Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello and was directed by William Asher, who also directed four other films in this series.[3]

Dick Dale and the Del-Tones and Stevie Wonder appear in musical numbers, the latter aged thirteen and making his film debut, billed as "Little Stevie Wonder."

The movie was released two days after Peter Lorre's death. (AIP had meant to star Lorre in It's Alive.[4])

Plot

[edit]Frankie, Dee Dee, and the beach party gang hit Malibu Beach for yet another summer of surfing and no jobs, only to find their secret surfing spot threatened by a gang of bodybuilders led by the dim-witted coach Jack Fanny. All the while a bored Italian countess is trying to steal Frankie from Dee Dee and, much to everyone's surprise, he seems more than happy to go along with it. Her plan is to turn him into a teen idol.

Due to some razzing from his former surfing buddies and sage advice from wealthy S.Z. Matts, Frankie sees the error of his ways and goes back to his American beach bunny, Dee Dee.

Cast

[edit]- Frankie Avalon as Frankie

- Annette Funicello as Dee Dee

- Luciana Paluzzi as Contessa Juliana ("Julie") Giotto-Borgini

- John Ashley as Johnny

- Don Rickles as Jack Fanny

- Peter Turgeon as Theodore

- Jody McCrea as Deadhead

- Dick Dale as Himself

- Candy Johnson as Candy

- Rock Stevens (Peter Lupus) as Flex Martian

- Valora Noland as Animal

- Delores Wells as Sniffles

- Donna Loren as Donna

- Morey Amsterdam as Cappy

- Little Stevie Wonder as Himself

- Buddy Hackett as S.Z. Matts (rich business manager)

- Dan Haggerty as Biff

- Larry Scott as Rock

- Gordon Case as Tug

- Gene Shuey as Riff

- Chester Yorton as Hulk

- Bob Seven as Sulk

- Steve Merjanian as Clod

- Alberta Nelson as Lisa, Jack Fanny's assistant

- Amadee Chabot as Flo, Jack Fanny's assistant

- Peter Lorre as Mr. Strangdour

Cast notes

[edit]Funicello reprises her character from Beach Party, although in this film (and three others that follow) she is referred to as "Dee Dee", as opposed to "Dolores." John Ashley's character, previously called "Ken", is now known as "Johnny."[5]

Harvey Lembeck's Eric von Zipper character and his Rats gang from Beach Party are absent in this film, although they appear in Bikini Beach, Pajama Party, Beach Blanket Bingo, How to Stuff a Wild Bikini, and The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini. Lembeck as von Zipper (but sans Rats gang) also appears in a cameo in Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine. Lembeck also appeared in Fireball 500, another Avalon-Funicello vehicle, as an entirely different character. Peter Lorre appears briefly near the end of the film and there is a notice explaining that he will appear in the next installment of the series. Lorre died in March 1964; thus, this was his only appearance in the series.[6]

Production notes

[edit]Before production producer Martin Ransohoff announced he was going to make a film called Muscle Beach based on Ira Wallach's satirical novel. This was eventually made as Don't Make Waves (1967).[1]

Filming started December 1963.

Novelization

[edit]A 141-page paperback adaptation of the screenplay, written by Elsie Lee, was published prior to the release of the film by Lancer Books.

Jack Fanny's bodybuilders

[edit]In the above-cited paperback novelisation, the Jack Fanny character (a satire of Vic Tanny) introduces his bodybuilders as Biff, Rock, Tug, Riff, Sulk, Mash and Clod, whereas in the film he calls them Biff, Rock, Tug, Riff, Sulk, Hulk, and Clod. In two separate sequences, the latter version of these names is seen printed on their shirts.

Larry Scott, who played Rock, was well known in the bodybuilding world at the time and became the first Mr. Olympia. Due to his preference for a piece of gym equipment commonly known as the Preacher Bench,[7] the bench also became known as the Scott Curl Bench.[citation needed] Gene Shuey who played Riff, and Chester Yorton who played Hulk, were also well known in the bodybuilding circuit. Peter Lupus (aka "Rock Stevens") was also a champion bodybuilder himself, holding the titles of Mr. Indianapolis, Mr. Indiana, Mr. Hercules, and Mr. International Health Physique. He is best known as Willy Armitage, the strong, mostly silent, member of the IMF team in Mission: Impossible from 1966 to 1973.[8]

Costumes and props

[edit]The swimsuits were designed by Rose Marie Reid; Buddy Hackett's clothes were from Mr. Guy of Los Angeles; and the hat that Deadhead wears was designed by Ed "Big Daddy" Roth.

The surfboards used in the film were by Phil of Downey, California – aka Phil Sauers, the maker of "Surfboards of the Stars."[9] Sauers was also the stunt coordinator for another beach party film that used his surfboards, Columbia Pictures' Ride the Wild Surf, which was released later the same year. Sauers was even portrayed in that film as a character by Mark LaBuse.

The "globe" telephone cover on Mr. Strangdour's desk is the same one in Norma Desmond's home in the film Sunset Blvd.

Music

[edit]The original score for this film, like Beach Party before it, was composed by Les Baxter.

Roger Christian, Gary Usher and Brian Wilson (of The Beach Boys) wrote six songs for the film:

- "Surfer's Holiday" performed by Frankie Avalon, Annette Funicello and the cast;

- "Runnin' Wild" performed by Frankie Avalon;

- "My First Love" and "Muscle Beach Party," both performed by Dick Dale and His Del-Tones;

- "Muscle Bustle" performed by Donna Loren with Dick Dale and His Del-Tones; and

- "Surfin' Woodie" performed a cappella by Dick Dale with the cast.

Guy Hemric and Jerry Styner wrote two songs for the film:

- "Happy Street" performed by Little Stevie Wonder; and

- "A Girl Needs a Boy" first performed by Annette Funicello, then reprised by Frankie Avalon as "A Boy Needs a Girl."

Opening title art

[edit]The colorful, hand-painted mural that is shown in full and in detail as background during the opening credits is by California artist Michael Dormer, whose surfer cartoon character, "Hot Curl" can also be glimpsed throughout the film.[10]

Deleted scene

[edit]Although the end titles provide a credit reading, "Muscle Mao Mao Dance Sequence Choreographed by John Monte, National Dance Director, Fred Astaire Studios", no such sequence is found in the film's release prints.

Reception

[edit]John L. Scott of the Los Angeles Times called it "a romantic, slightly satirical film comedy with songs which should prove popular with members of the two younger sets it concerns — surfers and musclemen — and with oldsters who don't mind the juvenile antics."[11]

Variety wrote that "the novelty of surfing has worn off, leaving in its wake little more than a conventional teenage-geared romantic farce with songs ... Whenever the story bogs down, which it does quite often, someone runs into camera range and yells, 'surf's up!' This is followed by a series of cuts of surfers in action. It's all very mechanical."[12]

The Monthly Film Bulletin stated, "Indifferently scripted, and lacking the brightening presence of Dorothy Malone and Bob Cummings, this is an excruciatingly unfunny and unattractive sequel to Beach Party. William Asher's direction remains quite bright, but that is about all that can be said for the film."[13]

Filmink argued the movie "feels short of a story strand or two" and was "a surprisingly gloomy film with a (relatively) lot of angst... the most serious of the series (maybe Frankie Avalon asked for the chance to ACT or something?)."[14]

The Golden Laurel, which had no ceremony but published its award results in the trade magazine Motion Picture Exhibitor from 1958 to 1971, nominated Annette Funicello for "Best Female Musical Performance" for this film in 1965.

The film was banned in Burma, along with Ski Party, Bikini Beach and Beach Blanket Bingo.[15]

Cultural references

[edit]- Don Rickles' character name "Jack Fanny" is based on then-popular bodybuilder and gym entrepreneur (and usually sharp-dressed) Vic Tanny. The forename "Jack" might also be a reference to another then-popular fitness instructor, bodybuilder, and gym-entrepreneur, Jack LaLanne.

- Julie's remark to an angry Dee Dee, "Have you tried Miltown?" is in reference to the drug Miltown by Wallace Laboratories, a carbamate derivative used as an anxiolytic drug – it was the best-selling minor tranquilizer at the time.

- Cappy's Place in this film (and Big Daddy's club in the preceding Beach Party) is a reference to Southern California beach coffeehouses in general and Cafe Frankenstein in particular.

- This is the second and last time Avalon or any other "teenager" in the cast smokes cigarettes onscreen in the series – the Surgeon General's report on smoking was released on January 11, 1964, while Muscle Beach Party was being filmed.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Gary A Smith, American International Pictures: The Golden Years, Bear Manor 2013 p 208

- ^ Lamont, John (1990). "The John Ashley Filmography". Trash Compactor (Volume 2 No. 5 ed.). p. 26.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (28 December 2024). "The movie stardom of Frankie Avalon". Filmink. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ "Poe & Bikinis". Variety. 9 October 1963. p. 17.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (December 2019). "A Hell of a Life: The Nine Lives of John Ashley". Diabolique Magazine.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Lisanti, Thomas (2005). Hollywood Surf and Beach Movies: The First Wave, 1959–1969. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 9781476601427.

- ^ Biceps curl

- ^ "Peter Lupus". IMDb. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ^ "Surfguide Magazine - the rise and fall".

- ^ "About Michael". Archived from the original on 2009-09-01. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ^ Scott, John L. (April 3, 1964). "'Muscle Beach Party' Juvenile Screen Fare". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 8.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Muscle Beach Party"". Variety. March 25, 1964. p. 6.

- ^ "Muscle Beach Party". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 33 (387): 62. April 1966.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (9 December 2024). "Beach Party Movies Part 2: The Boom". Filmink. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Four U.S. Films Banned in Burma". Los Angeles Times. Jan 21, 1966. p. c7.

External links

[edit]- Muscle Beach Party at IMDb

- Muscle Beach Party at the TCM Movie Database

- Muscle Beach Party at Brian's Drive In Theatre

- Muscle Beach Party at Music of the Beach Party Movies

- 1964 films

- 1964 comedy films

- 1960s teen comedy films

- American International Pictures films

- American sequel films

- American teen comedy films

- Beach party films

- Censored films

- Films directed by William Asher

- Films scored by Les Baxter

- Films set in Malibu, California

- Teensploitation

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s American films