Mysteries of Osiris

| Mystères d'Osiris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Religious festivities |

| Significance | Commemoration of the martyrdom of Osiris |

| Observances | procession of sacred boats,tributes to the dead |

| Begins | 12 Khoiak |

| Ends | 30 Khoiak |

| Started by | Ancient Egyptians |

| Related to | Nilotic Calendar |

The Mysteries of Osiris were religious festivities celebrated in ancient Egypt to commemorate the murder and regeneration of Osiris. The course of the ceremonies is attested by various written sources, but the most important document is the Ritual of the Mysteries of Osiris in the Month of Khoiak, a compilation of Middle Kingdom texts engraved during the Ptolemaic period in an upper chapel of the Temple of Dendera. In Egyptian religion, the sacred and the secret are intimately linked. As a result, ritual practices were beyond the reach of the uninitiated, as they were reserved for the priests, the only ones authorised to enter the divine sanctuaries. The most unfathomable theological mystery, the most solemnly precautionary, is the remains of Osiris. According to the Osirian myth, this mummy is kept deep in the Duat, the subterranean world of the dead. Every night, during his nocturnal journey, Ra, the solar god, came there to regenerate by temporarily uniting with Osiris in the form of a single soul.

After the collapse of the Old Kingdom, the city of Abydos became the centre of Osirian belief. Every year, a series of public processions and secret rituals were held there, mimicking the passion of Osiris and organised according to the royal Memphite funeral rituals. During the first millennium BC, the practices of Abydos spread to the country's main cities (Thebes, Memphis, Saïs, Coptos,Dendera, etc.). Under the Lagids, every city demanded to possess a shred of the holy body or, failing that, the lymph that had drained from it. The Mysteries were based on the legend of the removal of Osiris' corpse by Set and the scattering of his body parts throughout Egypt. Found one by one by Isis, the disjointed limbs are reassembled into a mummy endowed with a powerful life force.

The regeneration of the Osirian remains by Isis-Chentayt, the "grieving widow", takes place every year during the month of Khoiak, the fourth of the Nilotic calendar (straddling the months of October and November). In the temples, the officiants set about making small mummiform figurines, called "vegetative Osiris", to be piously preserved for a whole year. These substitutes for the Osirian body were then buried in specially dedicated necropolises, the Osireions or "Tombs of Osiris". The Mysteries are observed when the Nile begins to recede, a few weeks before the fields can be sown again by the farmers. Each of the ingredients used to make the figurines (barley, earth, water, dates, minerals, herbs) is highly symbolic, relating to the main cosmic cycles (solar revolution, lunar phases, Nile flood, germination). The purpose of mixing and moulding them into the body of Osiris was to invoke the divine forces that ensured the renewal of life, the rebirth of vegetation and the resurrection of the dead.

European Egyptosophy[edit]

In ancient times, Greek authors such as Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, Plutarch and Jamblicus developed the idea that Egypt, with its ancient civilisation, was the original cradle of all theological, mythological and ritualistic knowledge. This view is sometimes referred to as 'Egyptosophy', a word blend from the terms 'Egypt' and 'philosophy'. Since the Renaissance, this approach to the history of religions has had a major impact on Western culture. Its influence is particularly evident among those involved in Hermeticism, esotericism and pseudo-sciencism.[Note 1] Egyptosophy has thus influenced spiritual currents of varying degrees of occultism such as alchemy,[1] Rosicrucianism,[2] Freemasonry [3][4] and theosophy.[5] Since the decolonisation of Europe, Egyptosophy has also had a major influence on Western culture. Since the decolonisation of Africa, this idea has also become the cornerstone of Afrocentrist and Kemitist theorists, the latter seeking an "African renaissance" based on a return to the ancient Egyptian teachings.[6]

From the second half of the seventeenth century on wards, the cliché of "Egypt, land of mysteries" spread throughout the Europe of the Lumières. This commonplace was most perfectly displayed in the opera The Magic Flute by W. Mozart and E. Schikaneder, first performed in 1791.[7] In the middle of the work, the initiates Tamino and Pamina see their vision of the world turned upside down by their initiation into the Secrets by Sarastro, high priest of the Kingdom of Light and worshipper of the gods Isis and Osiris.[Note 2] At the same time, the Freemasons believed they had discovered the existence of a dual religion in the "Egyptian mysteries". Within a false polytheistic religion reserved for the common people, there was a true monotheistic religion reserved for a restricted circle of initiates. For the mass of uneducated people, religion was centered on piety, festivals and sacrifices to divinities. These are merely customs designed to maintain social peace and the continuity of the state. At the same time, in the subterranean shadows of the crypts beneath the temples and pyramids, Egyptian priests would have provided moral, intellectual and spiritual training to the elite in their quest for truth, during initiation ceremonies.[8] [Note 3]

The Mysteries and Egyptology Science[edit]

Textual sources[edit]

Since the 1960s, scientific knowledge of the Egyptian mysteries has progressed considerably thanks to the careful study of inscriptions left on papyrus or on the walls of temples and tombs. Numerous philological and archaeological contributions have challenged European cliches about the "Mysteries of Osiris", revealing the true nature of the rituals and the actual practices of the Egyptian priests. In the 1960s, the Egyptology community brought several major texts to the attention of the general public: firstly, Émile Chassinat's translation into French of the Rituel des mystères d'Osiris au mois de Khoiak, a compilation of Tentyrite inscriptions (this work dates back to the 1940s but was only published posthumously in 1966 and 1968, in two volumes, by the Institut français d'archéologie orientale-IFAO);[9] then the major publications of Papyrus N.3176 by Paul Barguet in 1962,[10] Papyrus Salt 825 by Philippe Derchain in 1964-1965[11] and the Cérémonial de glorification (Louvre I.3079) by Jean-Claude Goyon in 1967.[12] This work has since been supplemented by more recent works such as the exhaustive publication of the texts of the Osirian chapels atDendera by Sylvie Cauville in 1997,[13][14] Catherine Graindorge thesis on the god Sekeris at Thebes in 1994[15]and the contributions of Laure Pantalacci (1981),[16] Horst Beinlich (1984)[17]and Jan Assmann (2000)[18] on Osirian relics. At the same time, the archaeology of remains linked to the cult of Osiris has enriched our knowledge of the spaces dedicated to mystery rituals, such as the catacombs of Karnak and Oxyrhynchus.[19]

Mystery ritual of the Osireion of Dendera[edit]

In the academic world of Egyptology, knowledge of the "Mysteries of Osiris" is based mainly on late inscriptions from temples dating from the Greco-Roman period. Among these, the texts of the six chapels of the Osireion of Dendera (located on the roof of the Temple of Hathor) are the most important source. Our understanding of the ritual, its local variants and its religious context is based primarily on the Ritual of the Mysteries of Osiris, engraved at the very end of the Ptolemaic period. This source is rich in detail, but often confusing, as it is a compilation of seven books of different origins (Busiris and Abydos) and different periods (Middle Kingdom and Ptolemaic period). The inscription takes the form of a succession of one hundred and fifty-nine hieroglyphic columns arranged on three of the four walls of an open-air courtyard (the first eastern chapel). The first major translation into French was by Victor Loret in 1882, under the title Les fêtes d'Osiris au mois de Khoiak.[20] However, Émile Chassinat annotated translation, Le Mystère d'Osiris au mois de Khoiak (834 pages), published late in 1966 and 1968, remains the standard work.[9] In 1997, this translation was modernised, albeit almost unchanged, by Sylvie Cauville in her exhaustive publication with commentary of the texts of the Osirian chapels of Dendera.[13][14]

The nature of Egyptian mysteries[edit]

Secret rituals[edit]

Egyptian civilisation undeniably had secret rites. Most of the rituals performed by the priests were carried out behind the walls of the temples, in the absence of the general public. The general public generally had no access to the temple. On feast days, crowds were allowed into the forecourts, but never into the sanctuary's holy of holies. In the Egyptian mentality, djeser ('sacred') and seshta ('secret') are two notions that go hand in hand. The word 'sacred' also means 'to separate' or 'to keep apart'. In essence, then, the sacred is something that must be kept separate from the profane. Divine power is not confined to heaven or the beyond. Its presence also manifests itself on Earth among human beings. Temples, for the gods, and necropolises, for the ancestors, are places where priests exercise their role as mediators between humankind and the forces of the invisible. They are places apart, kept away from the majority of the living, and their access is subject to restrictions of all kinds, such as bodily purity, fasting and the obligation of silence.[21]

This clear distinction between sacred places and the profane world led the ancient Egyptians to endow sacredness with a strong obligation of secrecy. The priests who performed the rites in the temples were therefore bound to silence. They must not say anything about what they are doing. In the Book of the Dead, the deceased priest congratulates himself on having taken part in the cult ceremonies in the country's main towns and emphasises that he has disclosed nothing of what he has done, seen or heard.[22]

"The Osiris N [Note 4] will say nothing of what he has seen, the Osiris N. will not repeat what he has heard that is mysterious" —Book of the Dead, chap 133. Translation by Paul Barguet.[23]

Cosmic secrets[edit]

Solar journey[edit]

The two greatest divine powers, the most secret and most inaccessible, are Ra , the Sun god and Osiris of Abydos , the ruler of the dead. In his treatise The Mysteries of Egypt , devoted to the Egyptian and Babylonian religions, the Neoplatonist philosopher Iamblichus , summarizes in a short formula the two greatest mysteries of Egyptian belief:

If all things persevere in immobility and renewed perpetuity, it is because the course of the sun never stops; if all things remain perfect and complete, it is because the mysteries of Abydos are never revealed. — Jamblique, Les Mystères d'Égypte, VI, 7.

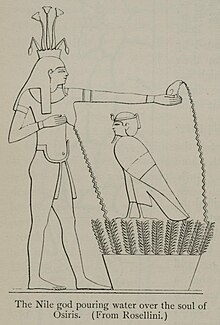

The path of the Sun inspired the Egyptians with a very abundant and developed religious literature. However, a clear distinction can be made as to their recipients. Some texts are clearly intended for the greatest number of people. These are hymns to the Sun, prayers addressed to the star at particular times of the day, in the morning when the star appears outside the mountains of the eastern horizon, halfway to celebrate its culmination and in the evening when it disappears on the western horizon. For most of the hymns, these are inscriptions engraved at the entrance to tombs, on steles placed inside or outside chapels or, even, on the papyri of the Book of the Dead . Accessible to all, these texts do not claim to transmit or ignore secret teaching. The other group of texts codifies and transmits knowledge reserved only for the pharaoh.[24] These are the Books of the afterlife: the Book of Amduat , the Book of Gates , the Book of Caves, etc. Their images and texts exclusively adorn the walls of the tombs of the sovereigns of the New Kingdom . They present, hour by hour, the nocturnal journey of the Sun through the lands of the beyond.[Note 5] This secret literature exposes the most occult of knowledge, the regeneration of the Sun deep within the Earth, that is to say its nocturnal renewal in a circuit which connects the end to the beginning in an existence freed from mortality. In the middle of the night, the solar star unites temporarily with the mummy of Osiris. From this union, he draws the life force necessary for his regeneration. Unlike the other deaths, the Sun does not become Osiris but rests within him, for a brief moment, in a single soul known under the name of "ba reunited", reunion of Re and Osiris or in the form of a criocephalic mummy called “The one with the ram’s head”:[25]

Re sets in the mountain of the West and illuminates the underworld with its rays.

It is Re who rests in Osiris, it is Osiris who rests in Re.

— Book of the Dead, chapter 15 (excerpt)

Osirian corpse[edit]

According to the occult literature of the Books of the Beyond, the greatest secret, the most unfathomable mystery of Egyptian beliefs, is the mummified remains of Osiris. In these texts, the sun god is "He whose secret is hidden", the underworld being the place "which shelters the secret". The word “secret” here designates the Osirian corpse on which the tired star comes to rest every night:

They keep the secret of the great god, invisible to those who are in the Duat. […] Ra said to them: You have received my image, you have embraced my secret, you rest in the castle of Benben, in the place which shelters my remains, what I am. —Book of Gates

The Egyptians had a custom of not talking about the death of Osiris. Generally speaking, from the Pyramid Texts to the Greco-Roman documents, the murder of Osiris, his mourning and his tomb are only evoked by allusions or by clever circumlocutions . We can thus read “As for the arou-tree of the West, it stands for Osiris for the affair which happened under him." (Papyrus Salt 825). The matter in question is, obviously, the burial of Osiris, the tree being planted on the site of the divine tomb. The Egyptians also used euphemisms, especially in the late period. So instead of saying “misfortune has befallen Osiris”, the statement is reversed by saying “misfortune has befallen the enemy of Osiris”. By postulating that speech and writing had within them a magical power, the Egyptians feared that the simple act of speaking of a mythical episode such as the death of Osiris risked making it happen again by simple enunciation. In the Papyrus Jumilhac, the murder of Osiris is thus eluded: instead of writing "Then Set threw Osiris to the ground", the scribe writes "Then he knocked the enemies of Osiris to the ground".[26]

Initiation to the mysteries[edit]

Egyptian texts say nothing about the existence of an initiation ceremony which would have allowed a new priest to access the temple and its theological secrets for the first time. We had to wait until the 2nd century, under the reign of the Roman emperor Hadrian, to encounter a text of this type. The source is not Egyptian, but the context is Egyptian. This is the initiation of Lucius, the main character of The Golden Ass, a novel written in the 2nd century by Apuleius of Madaure. The scene takes place not in Egypt, but in Greece, in Cenchrea, where there was then a temple of Isis. In this Greek context, it seems that the Hellenic followers of the Egyptian gods reinterpreted the Nilotic funerary rites, to stage them as an initiation of the living and not as a burial of the dead. The ceremony appears as an anticipated death and a descent into hell in order to approach the solar divinity during his union with Osiris. The question of the existence, in Egypt itself, of initiatory rituals remains largely controversial. While the idea of initiation is widely accepted in Egyptosophy circles, this possibility is mostly rejected by proponents of academic Egyptology. In Alexandria and Greece, in a syncretic interpretation, it is probable that the Osirian rituals merged with the Greek mysteries, such as those of Eleusis where young applicants were psychologically tested during nocturnal ceremonies, before receiving a revelation about the world divine.

There are therefore no Egyptian written sources suggesting an initiation of priests in the Pharaonic era. For the German Egyptologist Jan Assmann, it is however not aberrant to think that the ancient Egyptians acquired the secrets of the afterlife during their lifetime, in order to prepare for death. We can then imagine that the Egyptian myst was led, during a symbolic journey, into underground rooms, such as the Osireion of Abydos, the crypts of late temples, or into other places richly decorated with mystical illustrations and symbolic.[27]

Mysteries of Osiris in Abydos[edit]

From the Middle Kingdom, an annual religious festival took place in the city of Abydos, featuring the martyrdom and regeneration of the god Osiris. During secret ritual operations, officiants fashioned figurines and simulacra of relics. These sacred objects were kept for a whole year within the temple. They were then buried after being carried in procession to a specially dedicated necropolis. With the growing importance of the cult of Osiris, these mysteries took on national importance by being performed concomitantly in all the cities of the country during the month of Khoiak.

History[edit]

Abydos, holy city[edit]

Every year, during the month of Khoiak, in the city of Abydos, celebrations were held during which the statue of Osiris was carried in procession, out of his temple, to the Osirisirian tomb of Ro-Peker , probably located in the burial area known by the modern name of Umm El Qa'ab. During the Middle Kingdom, a historical period spanning the 11th and 12th dynasties, the ancient Egyptians likened the tomb of King Djer of the 1st Dynasty to themythical tomb of Osiris. This identification certainly finds its origin in the antiquity of the royal tomb, because more than a thousand years separate the two periods in question. During excavations carried out in 1897-1898, the French archaeologist Émile Amélineau discovered, in the mythical tomb, a statue of Osiris lying on his burial bed.[28] This discovery, however, remains controversial, the dating of this work not being formally established.[Note 6] Pilgrims flocked from all over the country to attend the processions and commemorated their passage with steles placed in chapels built along the ceremonial route. These festivities were celebrated throughout the New Kingdom, except during the Amarna period. Under the 19th dynasty, pharaonic munificence endowed the city with new cult complexes, such as the temple of Seti I and the Osireion. At the end of the Ramesside period, dynastic crises interrupted the success of Abydos, but the festivities regained their luster thanks to the political stability of the Saite period, during which numerous memorial stelae flourished again.[29]

Origins of the preponderance of Abydos[edit]

The religious fame of the Osirian Mysteries of Abydos[Note 7] dates back to the First Intermediate Period, a time of social unrest resulting from the decay of the state institutions of the Old Kingdom. Previously, during the prosperous age of the Pharaonic monarchy, splendid necropolises made up of mastabas were organized around the Memphite pyramids. These places of eternity allowed any deceased notable to benefit from the immediate vicinity of the royal funeral cult and to benefit from the generous redistribution of food offerings. With the disappearance of these necropolises, Abydos, the ancient cemetery of the first pharaohs (Thinite era), symbolically takes over by becoming the ideal necropolis to which every dignitary must refer to hope for post-mortem salvation. The god Osiris, the mythical paragon of the dead pharaohs, becomes the great god of the necropolis by ousting the jackal god Khenti-Amentiu. The Mysteries of Abydos , centered on the martyrdom of Osiris, are in fact nothing other than the transposition of the royal funerary ritual from the time of the pyramids into a divine ritual repeated annually. At the same time, in Memphis, a similar annual funerary festival developed around Seker, the mummified falcon god. The basic structure is the same. In place of the remains of the dead pharaoh, a ritual is set up based on a simulacrum of a body, a mummiform effigy fashioned for eight days, followed by a liturgical vigil during a sacred night ( Haker festival in Abydos; Netjeryt festival in Memphis) and a funeral procession intended to convey the effigy to its tomb (thanks to the neshmet barque in Abydos and the Hennu barque in Memphis).[30]

Coming out to daylight[edit]

From the Middle Kingdom, the idea emerged among the ancient Egyptians that the religious festival was a sacred period during which the ancestors could “return to daylight” ( peret em herou ) from the underground world of the dead in order to participate in the celebrations. festive performances performed by the living, their descendants. For the duration of the celebration, the opposition between here below and the beyond is abolished or, at the very least, diminished. The statues of the deities emerge from the solitude of their sanctuaries and appear to the crowd. The living visit their deceased in the necropolises. The Akh (“ancestral spirits”), thanks to their Ba (“soul”), return the favor to humans by participating, as a family, in banquets and celebrations. In the Middle Kingdom, steles mention the wish to participate post-mortem in the great religious festivals of the “Mysteries of Abydos” which are the annual reiteration of the myth of Osiris through the grace of the ritual. The highlight of this mystical event is the procession of a statue of Osiris in a portable boat from his temple at Abydos to the sacred mound of Ro-Peqer (the mythical tomb of the god), located less than two kilometers to the south of the holy city. According to the myth, the god was assassinated by his brother Set and regenerated by his wife Isis in the form of an eternal mummy deposited in this place. Subsequently, during the New Kingdom, this desire to participate jointly, living and ancestors, in a festive moment, extended to other celebrations (Abydean, Theban, Memphite and other festivals) while leaving the religious preponderance to the "Mysteries of Abydos”. This fact has a lasting impact on Egyptian funerary thought until the end of ancient civilization and is expressed, most perfectly, in the corpus of the Book of the Dead or "Book for emerging into the light", a sort of vade mecum showing the geography , the dangers, the dodges and the paths to the afterlife for the deceased wishing to come and go between the two worlds.[31]

National cult[edit]

During the first millennium BC, although ancient Egypt was in its twilight, it remained a living civilization where religious beliefs underwent profound changes. From the 6th century, the country of the Nile gradually lost its political independence by being the victim of a succession of foreign occupations (Persians, Nubians, Macedonians, Romans). The Egyptian elites, politically downgraded by these external authorities, then took refuge within the temples to maintain their income, their prestige and their social status. This clericalization of culture leads to the production of intense theological reflections.[32] The ancient traditions are rethought and developed into a very complex symbolic system, based in particular on the myth of the dismemberment of Osiris and the demonization of the god Set.[Note 8] The written culture of hieroglyphics was profoundly modified, with the number of signs multiplied tenfold. Learning to write becomes an extremely difficult art requiring around ten years of study. It is probable that this complexity produced a break between the mass of the Egyptian people and the priests busy with their magico-religious speculations behind the surrounding walls of the temples.[Note 9] The most important change is the growing importance of the cult of Osiris. The devotion shown to him leaves the funerary domain, where he was strictly confined since the Old Kingdom, to reach individuals in search of a religion of salvation. The Osirian belief spread outside its original metropolises of Abydos, in the south, and Busiris, in the north, to reach all the cities of the country where, within each temple, chapels dedicated specifically to the Mysteries developed.[19] The most famous example is the Osireion of Dendera, a complex of six chapels located on the roof of the temple of Hathor.[33]

Progress of the Abydean festivities[edit]

Stele of Ikhernofret[edit]

During the Middle Kingdom , the pharaohs Sesostris I , Sesostris III AND Amenemhat I showed great interest in the holy city of Abydos and its temple dedicated to Osiris - Khentymentyou . They sent trusted men there whose mission was to fill the temple with riches, to undertake renovations and above all to lead, by taking an active part, the processions reenacting the mysteries of the martyrdom of Osiris. One of the most important testimonies of this era is the stele of the treasurer Ikhernofret , discovered in Abydos and now exhibited in the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin .

“I played the exit of the “Opener of the Roads”, when he advances to avenge his father; I drove the enemies from the ship Neshmet, I drove back the enemies of Osiris. I then played a grand exit, accompanying the steps of the god; I allowed his boat to sail, while Thoth directed the navigation rightly. I had equipped the boat [called] “She who appears in glory thanks to Truth-Justice” with a beautiful chapel, and, having fixed her beautiful crowns, here is the god who advances towards Peker, I cleared the path which leads to his tomb facing Peker. I avenged Ounennéfer (= Osiris), on that famous day of the Great Battle, and I destroyed all his enemies on the shore of Nedyt. I made him advance inside the boat (called) “the Great” and that it bore his beauty. I gladdened the hearts of the hills of the western desert, I created exultation in these hills, when "they" saw the beauty of the boat Neshmet, while I landed at Abydos, (the boat) which brought back Osiris, lord of the city, towards his palace. I followed the god into his house, made him purify himself and return to his throne..." —Translation by Claire Lalouette[34],Stele of Ikhernofret (extract).

The festivities take place in the form of a succession of processions, each of them recalling an episode from the Osirian myth. The senior figures who were brought to participate, although they testified to their presence by placing steles, nevertheless placed their written testimonies under the protection of a pious secret. Several processes have been implemented to guarantee the greatest possible discretion for the “Mysteries of Abydos”. Many writings, including that of Ikhernofret, cite the rites and processions out of order so that they are less understandable. These rituals are, moreover, described at a minimum using stereotypical sentences which in no way reveal the details. Another process is to make a sacred object like the portable boat unrecognizable by camouflaging it under a graphic simplification.[35]

Public processions[edit]

The Abydean steles never mention the assassination of Osiris , but this episode was probably played out during the statue's exit from the temple, where attackers, supporters of Set, seized the figure in order to throw it away. on the ground and leave it there, lying on its side. After this tragic episode, the steles mention the processional exit of the péret tepyt , also called “Exit of Wepwawet” or “Exit of Sem”. A high character playing the role of the canine god Wepwawet, the “Opener of Paths”, comes to save his father Osiris by driving away the attackers and performing the rites of mummification on the statue. The canine divinity is here a manifestation of Horus who fights, in the name of his father Osiris, his Setian enemies. The hostile and enemy forces are, perhaps, symbolically crushed during a magical ritual where wax statuettes and vases representing them are mishandled, then destroyed. It was then necessary to carry out the funeral of the statue of Osiris by taking it to its tomb in Ro-Peker. This took place in three stages. During the “Grand Exit” outside the temple, a funeral procession led by Wepwawet was acclaimed by the crowd of faithful. It was then necessary to cross a body of water by boat- undoubtedly the sacred lake of the temple - under the protection of Thoth, to symbolize the passage to the beyond. For the last part of the journey, the god was placed on a funeral sleigh to reach the necropolis, accompanied by a few officiants.

The culminating moment of the mysteries is the implementation of the regeneration of Osiris in the “Abode of Gold”, probably located near the tomb. According to the words of King Neferhotep I of the 13th Dynasty, a new statue was made from gold and electrum. The texts do not, however, specify the time of this rite, which must have taken place during the preparations for the processions or after the funeral of the previous statue. During Haker Night, an officiant was supposed to capture the spirit of Osiris so that the statue could be considered alive and inhabited by the god. This night corresponds, in the funerary cult, to the night of justification, where the judgment of the dead is ritualized during nightly vigils. This accomplished, the news was announced to the living and the dead, in common exultation. The statue then left Ro-Peqer in a sacred boat to reach the temple.[35]

Fashioning of Osirian statuettes[edit]

If the processional outings of the “Mysteries of Abydos” in the month of Khoiak took place in public, other rites were performed away from profane eyes by officiants forming a confidential circle. Each year, during the days preceding the processions (or concomitantly), new statues of Osiris were made from a mixture of earth, barley grains and other precious components. The ritual shaping of these divine representations constituted the heart of Abydaean celebrations. The Ikhernofret stele does not provide any information as to the appearance of these statues but specifies, all the same, that they were decorated with gold and precious stones:

I adorned the chest of the statue of the lord of Abydos with lapis lazuli and turquoise, electrum and all kinds of precious stones used to adorn his divine limbs. I adorned the god with his crowns, according to my office as steward of secrets and my function as priest. A sem priest with pure hands, my hands were undefiled to adorn the god. —Stele of Ikhernofret (extract). Translation by Claire Lalouette[36]

None of these statuettes have been discovered at Abydos during archaeological excavations. This description, however, agrees with later artifacts discovered on other sites and known under the scholarly name of “vegetating Osiris” (as know in English: Corn mummy; in German: Kornosiris / Kornmumie ). The latter, around fifty centimeters high, are frequently decorated with gold leaf or placed in small golden sarcophagi with falcon heads.[37]

Relics of Osiris[edit]

The ancient Egyptians did not worship relics (body parts or personal belongings) left behind by a saint or hero after death. Like the deities of the pantheon, the veneration of ancestors was preferentially exercised through the mediation of cult statues. The notion of relic is, however, not absent from religion. It is mainly based on the myth of the dismemberment of Osiris by Set. Traditions thus attest to the presence of this or that part of the Osirian body in certain cities of the country. The materiality of these relics was manifested in the annual production of figurines of the body of Osiris and simulacra of relics.

Myth of the dismemberment of Osiris[edit]

Commemorating the actions of Isis[edit]

The largest part of the “Mysteries of Osiris” ceremonies, performed during the month of Khoiak , took place within temples away from profane eyes. Only the “ Ritual of the Mysteries of Dendera”, engraved on the walls of one of the six Osirian chapels of the temple of Hathor (Greco-Roman period), records the essentials of these ritual gestures. This collection is a late compilation of seven books which explains, in a sometimes confusing manner, the making and burial of three sacred figurines fashioned in the image of the god Osiris. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, scholars such as Alexandre Moret and James George Frazer attributed a purely agrarian character to the rites of the “Mysteries of Osiris” by overinterpreting the text of Dendera. Ptolemaic hieroglyphic writing being difficult to approach, these two commentators, misled by translation errors due to Victor Loret, endowed the “Ritual of the Mysteries” with excessive symbolism which it does not contain. Since the work of Émile Chassinat, in the middle of the 20th century, it is now clearly established that the mysteries are the commemoration of the martyrdom of Osiris: his dismemberment by Set and his funeral after his reconstitution by Isis and Anubis. During the month of Khoiak, the priests reconstituted (or re-enacted), within the temples, the main acts and gestures accomplished by the goddess Isis after the murder of her husband. Thanks to fragile sacred figurines, the priests renewed each year the reconstruction of the dismembered body of Osiris, as well as his sumptuous funeral.[38] The central divinity of the ritual is the goddess Isis, mentioned mainly under her name Chentayt , “She who suffers”, a term which designates the widow. In places, the texts split it by speaking of a “Chentayt of Busiris” and a “Chentayt of Abydos”. This is how the making of the Osirian figurines took place in a room of the temple called the “Residence of Chentayt” in the presence of a statue showing her lamenting.[39]

Quest for Isis[edit]

At the beginning of the 2nd century, the Greek Plutarch reported an Egyptian tradition which placed the institution of the “Mysteries of Osiris” in the mythical times of the divinities:

When [Isis] had stifled the madness of Typhon and put an end to his rage, she did not want so many fights and so many struggles sustained by her, so many wandering races, so many strokes of wisdom and courage remained buried in silence and oblivion. But, through figurations, allegories and representations, she unites with the most holy initiations the memory of the evils she had then endured, thus consecrating at the same time a lesson of piety and encouragement for men and women. who would fall under the influence of such adversities. —Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris,§ 27.Translation by Mario Meunier[40]

Plutarch offers in his philosophical treatise, On Isis and Osiris , the first narrative version of the Osirian myth, a story only evoked by disparate allusions in Egyptian sources.[41]

While Osiris reigned over the Egyptian people, his jealous brother Set decided to assassinate him in order to ascend the royal throne. During a banquet, Set, helped by seventy-two cronies, succeeded by trickery in locking Osiris in a magnificent chest which he then threw into the waters of the Nile.[Note 10] The goddess Isis, the wife of Osiris, searched for the body of her husband and this quest brought her to the city of Byblos located in Phoenicia. Isis collected the chest from King Malcander and brought it back to Egypt.[42] From there, the story enters the crucial phase regarding the institution of the Mysteries:

Isis, before setting out to go to her son Horus, who was brought up in Buto, had deposited the chest where Osiris was in a secluded place. But Typhon , one night when he was hunting by moonlight, found him, recognized the body, cut it into fourteen pieces and scattered them on all sides. Informed of what had happened, Isis set out to look for them, boarded a boat made of papyrus and traveled through the marshes. […] This also explains why several tombs in Egypt are said to be the tomb of Osiris, because Isis, it is said, raised a tomb each time she discovered a section of the corpse. —Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris,§ 18. Translation by Mario Meunier[43]

Sacred relics[edit]

The myth of Osiris dismemberment by Set has been attested throughout Egyptian texts since the time of the Pyramid Texts. The sources are, however, disparate and discordant depending on the places and times considered. The number of relics (12, 14, 16, 26 or 42) collected by Isis or Anubis, as well as the distribution of members across the territory, their very nature - body parts or regalia (scepter, crown) - are subject to significant variations.[44] Divergences are sometimes found even within the same source if it is a compilation of varied traditions . As far as we know, the oldest list of relics dates from the New Kingdom and is in the form of a magical formula where the practitioner threatens to reveal the secrets of the tombs of Osiris (Chester Beaty Papyrus VIII). This text cites the cities of Athribis, Heliopolis, Letopolis, Mendes and Heracleopolis and attributes to them a lot of relics which can be up to five for the same city.[45] The Jumilhac Papyrus (Ptolemaic period), which reports traditions limited to the Cynopolitan region (17th and 18th nomes of Upper Egypt), presents two divergent lists of twelve and fourteen relics found across the country thanks to the efforts of Anubis. The temples of Edfu and Dendera present, for their part, the myth of the consolidation of Osiris in the form of a procession of forty-two genies, symbols of the forty-two nomes of the country, bringing the holy relics under the guidance of pharaoh, in order to reunite them.[46]

| Discovery Day | Disjointed Limb

(Relic) |

Place of

discovery |

|---|---|---|

| 19 Khoiak | 1 - 2/ Head | 1 - 2/ Abydos |

| 20 Khoiak | 1 - 2/ Eyes | 1/ Eastern Ghebel |

| 21 Khoiak | 1 - 2/ Jaws | 2/ 3rd of Upper Egypt |

| 22 Khoiak | 1/ Neck

2/ arms |

1/ Western Ghebel

2/? |

| 23 Khoiak | 1/ Heart

2/ Intestines |

1/ Athribis

2/ Pithom |

| 24 Khoiak | 1/ Intestines

2/ Lungs |

1/ Pithom

2/ Béhédet du Delta |

| 25 Khoiak | 1/ Lungs

2/ Phallus |

1/ Delta marshes

2/ Mendès |

| 26 Khoiak | 1/ Jaws

2/ Two legs |

1/ in a gejet

plant 2/ Iakémet |

| 27 Khoiak | 1/ Leg

2/ Fingers |

1/ Eastern region

2/ 13th and 14th Nomes of Upper Egypt |

| 28 Khoiak | 1/ Phallus

2/ Arm |

1/ Middle region

2/ 22nd Nome of Upper Egypt |

| 29 Khoiak | 1/ Viscera

2/ Heart |

1/?

2/ Athribis you participate |

| 30 Khoiak | 1/ Arms

2/ Four canopies |

1/?

2/? |

| , Khoiak | 2/ Flagellum | 2/ Letopolis |

| , Khoiak | 2/ Heka-scepter | 2/ Heliopolis |

Simulacra of relics[edit]

When Plutarch speaks of the quest for Isis and the disjointed limbs of Osiris, he accounts for two different explanations. The first, mentioned above, affirms that each member found by Isis is indeed buried in the holy city where it was discovered. The second explanation, however, considers that the tombs contain only simulacra intended to deceive and confuse Set in his destructive madness:

Isis made images of everything she discovered, and she gave them successively to each city, as if she had given the whole body. She thus wanted Osiris to receive as many honors as possible, and for Typhon, if he were to prevail over Horus, to be lost and deceived in his search for the true tomb of Osiris by the diversity of everything that we could show him. The only part of Osiris' body that Isis could not find was the virile member. As soon as it was snatched, Typhon threw it into the river, and the lepidote,[Note 11] the porgy and the oxyrrhynpus had eaten it: hence the sacred horror that these fish inspire. To replace this member, Isis made an imitation of it, and the Goddess thus consecrated the Phallus, the festival of which the Egyptians still celebrate today. —Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris,18. Translation of Mario Meunier[48]

According to the historian Diodorus Sicily(1st century),[49] the goddess Isis developed a ruse to deceive the priests in order to encourage them to celebrate the memory of Osiris. Each time she found a member, she mummified it by placing it in a human-shaped simulacrum in the likeness of Osiris:

Isis found there all the parts of Osiris' body, except the sexual parts. To hide the tomb of her husband, and have it venerated by all the inhabitants of Egypt, she proceeded in the following manner: she enveloped each part in a figure made of wax and aromatics, and similar in size to Osiris, and summoning all the classes of priests one after the other, she made them swear to the secrecy of the confidence she was going to make to them. She announced to each of the classes that she had entrusted to him, in preference to the others, the burial of Osiris […] —Diodorus of Sicily, Historical Library, I, 21.Translation by Ferdinand Hoefer[50]|

Typology of figurines[edit]

The Ritual of the Mysteries of Osiris[Note 12] from the temple of Dendera explains the methods of making three figurines which correspond to the statements of Plutarch and Diodorus of Sicily presented above; two simulacra of the entire body, the Khenti-Amentiu and the Seker and a simulacrum of the relic, the “Divine Lamb” which is to be interpreted as the member of Osiris specific to a city.

The Khenti-Amentiu[edit]

The figurine called Khenti-Amentiu represents Osiris in his aspect as civilizing sovereign, the pharaoh who rescued the Egyptian people from the barbarism of the early ages.[51] It is made from a mold of two gold pieces having the appearance of half a mummy cut from top to bottom. One of the pieces was used to mold the right side of the figurine, the other the left side. The two parts put together, the figurine took the appearance of a mummy with a human face, wearing a white crown. The two pieces of the mold are used as planters in which barley seeds are germinated, in a sandy soil kept moist by daily watering (from Khoiak 12 to 21). The shoots having germinated, the two halves are tied together to give it its final shape.[52] The dimensions of Khenti-Amentiu are modest, in total one cubit high and two palms wide, i.e. 52 × 15 cm (Book II,17).[53] The mold allows the figurine to be named thanks to an inscription engraved on the chest: “King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Pharaoh Seker, loved by the begetter who begat himself” (Book V, 41).

The Divine Shred[edit]

According to the Ritual of the Mysteries of Dendera, the sepy netjer or “divine shred” is of the same composition as the Khenti-Amentiu (barley and sand). It is cast in a square box made up of two symmetrical bronze parts, each measuring 28 cm on a side and 7.4 cm in height. According to Émile Chassinat , the “Lambeau” is undoubtedly the symbolic representation of all the fourteen relics of the body of Osiris.[54] The two figurines of Khenti-Amentiu and “Lambeau” remain together, between Khoiak 12 and 21, in a square greywacke garden vat; it is 65 cm wide and 28 cm deep and pierced at the bottom to allow excess water from daily watering to drain away. The tank rests on four pillars and, under it, is placed a sort of granite basin which collects the excess liquid.[55]

According to the Belgian Egyptologist Pierre Koemoth,[56] it seems that the “Divine Shred”, as a relic of the dismembered body of Osiris, could be materialized by a plant during the Khoiak ceremonies. The shred was undoubtedly sought by the priests on the banks of the Nile in imitation of the quest for Isis. The Egyptian texts are obscure on this subject, but a passage from the Jumilhac Papyrus seems to mention this fact:

The 26th (of Khoiak), is the day when the jaws ( ougit ) established in a plant ( git ) were found.[57]

An inscription from the Canopic Procession, appearing in the Osireion of Dendera, has Ra Horakhty saying that he discovered the femur of Osiris in the reed beds of the Heliopolis region:

“I bring you the bone ( qes ) of the forearm that I found in the place called “Plants of the Gods and Goddesses,” and I put it in its place in the Golden Room.

Here the relic appears in the form of the reed ( is ), a plant with a stiff stem. This fact is to be linked with Egyptian language expressions such as qes in isy (“reed bones”) which is used to designate the stems of this plant or qes in khet (“tree bones”) to name the branches.[58] The ceremonial of the Inventio Osiridis or “discovery of Osiris”, is well known from the Greco-Egyptian rituals of the Isiac cults.[59] Plutarch reports, certainly for the night of 19 Hathyr , that the believers thought they could find Osiris in the waters of the Nile:

There, the stolists and the priests bring a sacred cist which contains a small golden box into which they pour fresh water. A clamor arose from those present, and everyone shouted that Osiris had just been found. After that, they soak the topsoil with water, mix with it expensive herbs and perfumes, and shape it into a crescent-shaped figurine. They then dress her in a dress […] —Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris, § 39 (excerpt). Translation by Mario Meunier[60]

And Seker[edit]

The Seker (or Sekeris) figurine represents King Osiris in his role as divine ruler and protector of the dead.[51] According to Émile Chassinat, the Seker is the representation of the body of Osiris dismembered by Set and reconstituted by Isis. This figurine is molded from a compact and ductile paste , made of sand and crushed dates, into which other expensive ingredients are also incorporated, including twenty-four precious stones and minerals.[61] The Seker mold is the same length as that of Khenti-Amentiu , namely one cubit (52.5 cm ). However, its appearance is different. One of the parts is used to mold the front side of the body and the other the rear side. Put together, the Seker statuette thus takes the form of a mummy with a human head wearing a nemes, with a uraeus on the forehead, and holding in its two hands the crozier and the whip crossed on the chest (Book III , 32- 33).[62] The Ritual of the Mysteries of Osiris has left us three recipes for the dough used to make it (Book III , 33-35; Book VI , 117-121 and Book VII , 135-144), the last, explained below, is the most detailed.

Make a mummy with a human face, wearing a divine wig and the ibes headdress, crowned with the uraeus, grasping the heka scepter and a flabellum, whose name is engraved on a cartouche as follows: “Horus Arbitrator of separation of the Double Country, Osiris lord of Busiris, Onnophris Khentymentyou, god great lord of Abydos”.

Take: Date pulp, earth, seven khait[Unit 1] each, 1/3 of hin for each, or by weight three deben , three qites 1/3 for each.[Unit 2]

Take: Water from the Andjti nome and the sacred lake, two 1/2 hours . Moisten 1/3 of the Khait date pulp .

Work it perfectly and cover it entirely with sycamore branches so that it remains ductile.

Myrrh (kher) of the first quality, four khait 2/3, or by weight of 1/4 of each of them, namely seven qites 1/2 for each.

Fresh turbinth resin packaged in palm fiber, one kait 2/3 1/12, or similarly by weight 1/4 1/8 qite for each.

Sweet aromatics, twelve in total, of which here is the list:

aromatic reed (sebit nedjem): two qites, gaiou aromatic of the oasis: two qites, cinnamon (khet nedjem): two qites, resinous wood of pine Aleppo: two qites , fedou plant: two qites, Ethiopian rush: two qites, djarem aromatic: two qites, peqer aromatic: two qites, mint (nekepet): two qites, pine nuts (perech): two qites, juniper berries (peret in ouân): two qites .

Grind then sift.

Twenty-four minerals, of which here is the list:

gold, silver, carnelian, and still the list: dark red quartz, lapis lazuli, turquoise from Syria, turquoise in pieces, green felspar from the North, calcite, red jasper, tjemehou mineral from the country from Ouaouat, senen mineral , dolerite (nemeh), magnetite, chrysocolla and galena together, green stone in pieces, seheret resin in pieces, amber, black flint (des kem), white flint (des hedj), amethyst from the land of the Blacks.

Grind them and put them in a cup then mix them.

Add the date paste to them: 1/3 khait .

Which makes a total of seventeen kait 1/12.

Here is the summary:

earth: sevenkhait , date pulp: seven khait , myrrh (kher): two khait 1/3, terebinth resin: one khait 2/3, aromatic pleasant smell: one khait 1/6, minerals 1/6 of khait

—Ritual of the Mysteries of Osiris. Translation by Sydney H. Aufrere[63]

Places of celebrations[edit]

Scientific knowledge of the “Tombs of Osiris”, where the figurines of the god are permanently buried, has been enriched thanks to French archaeological excavations at Karnak in 1950-51 and since 1993, and those of Hispano-Egypt at Oxyrhynchus since 2000. D Other sites are attested by archaeology, such as the city of Coptos.

Holy cities[edit]

Sixteen cities[edit]

According to the Ritual of the Mysteries of Osiris, the Osirian festivals of the month of Khoiak are celebrated "in all the nomes of the sixteen members of the god and in the divine nomes" (Book I, 14), or "in all the nomes of Osiris" (Book VI, 100), that is to say the sixteen Egyptian provinces where, according to the myth, the shreds of the body of Osiris torn to pieces by Set have been preserved since the quest for Isis . This number is symbolic; Pliny the Elder reports that the flood of the Nile varies depending on the year from one to sixteen cubits in height, sixteen being the optimal number to hope for good harvests after the withdrawal of the waters.[Note 13] The number sixteen marks a desire to limit ourselves to the most prestigious cities. But, with the development of the cult of Osiris during the first millennium BC, all the regional sanctuaries rallied to the cult of Osiris and integrated the rituals of Khoiak into their cult traditions, as evidenced by the Osireion ofDendera, built on the terrace of the temple of Hathor, or the Osireion of Thebes, built in the Precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak.[64]

Local rites[edit]

The Dendera text gives a general overview of the Osirian mysteries, but provides very little information on the local particularities of these celebrations. Of the twenty cities mentioned, the collection nevertheless identifies two groups of distinct rituals. The first geographical group followed the rites of Abydos and brought together cities of Upper and Lower Egypt such as Elephantine, Coptos, Cusæ, Heracleopolis, Letopolis , the 4th nome of Lower Egypt, Bubastis, Heliopolis and Athribis. The second, more modest, included the towns of Busiris and Memphis.[65]

Some cities did not follow the general rule. In Saïs, the Khenymentiou figurine was not made from a mixture of earth and barley, but modeled by a sculptor from clay mixed with terebinth resin and sprinkled with barley grains (Book II,30-31). In Diospolis , the “divine shred” was replaced by a representation made from bread flavored with herbs (Book I,6-7).[66]

Bousiris[edit]

The site of Bousiris , located in the Nile Delta, has yielded very few archaeological elements.[67] According to indications provided by the Ritual of the Mysteries of Osiris , the tomb of Osiris at Bousiris was in the form of a chapel sheltered under a sacred tree (Douât superior) and a crypt located under a tumulus (lower duat).

Upper duât[edit]

From the twenty-fourth of Khoiak and during the last seven days of the month, the sacred effigies of the previous year rest in a place called “Upper Duat”. It is perhaps a sort of chapel-tomb located next to a sacred tree and which then served as a temporary burial place awaiting the thirtieth of Khoiak, the day of the last ceremonies. During this week, the Seker-Osiris figurine is known as “Unique in the Acacia”. A bas-relief from the Osireion of Dendera shows the figurine in its sarcophagus, lying in a tree. The branches spread above and below the pseudo-mummy, all around the coffin, undoubtedly to make it clear that Osiris is placed under the protection of this tree. This figuration recalls the mythical episode reported by Plutarch where, in Byblos, a tamarisk tree had greatly activated its growth in order to hide, inside its wood, the sarcophagus containing the remains of Osiris (Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris , §15. Translation by Mario Meunier).[68]

Lower duat[edit]

The Ritual of the Mysteries of Osiris indicates that the sacred figurine of the previous year is definitively buried during the night of the thirtieth Khoiak in a place called “Lower Duat”. In the town of Busiris, this is a crypt located under a sacred mound planted with one or more ished trees, probably balanites:

As for the crypt of the ished tree which is in the divine cemetery, one enters it with the mystical work of the previous year; this is what we call the lower Duat. It is made of stone. Its height is sixteen cubits; its width twelve cubits. It has seven doors similar to the Douat door. There is a door to the west through which one enters, a door to the east through which one exits. It contains a pile of sand of seven cubits, on which the god is placed inside the sarcophagus. —Ritual of the mysteries of Osiris, Book V, 80-82. Translation by Émile Chassinat.[69]

According to the description given in the ritual text, the Busirite crypt was a stone building covered by an artificial hill. The ground level had to be lower than that of the entrance in order to allow the stagnation of water during the flooding of the Nile during the month of Khoiak during which the burial took place. The mound of sand was undoubtedly intended to keep the small sarcophagus of figurine above ground.[70]

Abydos[edit]

Ou-Peker[edit]

( Geographic coordinates: 26°10′30″N 31°54′32″E / 26.1751°N 31.909°E )

Since the archaeological excavations of Émile Amélineau in 1897, it is generally accepted that the site of Ou-Peker is to be located in Umm El Qa'ab on the site of the former royal necropolis of the Thinite sovereigns. In this cemetery built at the foot of the mountains of the Libyan desert, the ancient Egyptians assimilated the tomb of King Djer of the 1st dynasty to the Areq-heh, the Abydean tomb of Osiris. A processional route, or perhaps a canal, connected the temple of Osiris to this tomb. On numerous stelae, the deceased declare that they wish to pass through the site of Ou-Peker in order to receive, during the days of Khoiak, a crown of justification. This crown offered by Osiris is a symbol of legitimacy and eternity. It had to be woven from branches taken from the trees that grew along the sacred path, probably date palms . According to demotic sources , the soul (ba) of Osiris fluttered under these trees and received food placed on 365 offering tables. This orchard also housed a vineyard in order to provide wine for the daily libations poured on the altars.[71] In 1952, the German Egyptologist Günther Roeder proposed comparing the garden vat (hezepet), where germination takes place, to the figurines of the “sacred domain” (hezep) of Abydos where flowers, vines and vegetables grew dedicated to Osiris. During the Late Period, the garden vat of the Mysteries would then have symbolically reflected the domain of Ou-Peqer by constituting, within the different temples, a reduced form of the Osirian agricultural domain.[72]

Osireion of Abydos[edit]

( Geographic coordinates: 26°11′03″N 31°55′07″E / 26.1842°N 31.9185°E )

The Osiréion of Abydos, discovered in 1903, is an unrivaled construction, built by Seti I at the rear of his funerary temple. With its Egyptian name "Beneficent is Menmaâtre to Osiris", the building is dedicated to Osiris and presents itself as a cenotaph whose history and meaning are still debated. However, it seems to reproduce the tomb of Osiris as the ancient Egyptians imagined it. Today gutted, only the underground parts remain. Originally, the main room was supposed to support, above it, an artificial earthen mound (tumulus) planted with one or more sacred trees. The Osireion is massive, with the aim of imitating the archaic appearance of the temples of the early Old Kingdom. However, it takes up the plans of the royal hypogeums of the New Kingdom, all characterized by a long hallway leading to a series of funerary chambers. The central space evokes an island surrounded by a canal. This island represents the primordial mound surrounded by the waters of the Noun , on which Atum-Re, the creative solar god, appeared. The axis of the island is marked to the east and west by two staircases plunging into the canal. In the center are dug two rectangular cavities whose purpose was, perhaps, to accommodate a simulacrum of a sarcophagus and a chest of canopic vases.[73] If this is the case, it is not impossible to imagine that Osiréion housed within it an Osirian figurine created during the Mysteries and renewed each year.

Osireion of Karnak[edit]

The Osireion site of Karnak (Thebes) allows us to follow the evolution of the ritual of burial of sacred figurines over nearly a millennium, from the New Kingdom to the Lagid period. This Osirian complex is located inside the enclosure of Amun-Re, behind the main temple dedicated to the demiurge Amun . It is made up of the tomb itself, the first traces of which date back to the end of the New Kingdom, as well as several chapels built from the 22nd dynasty, dedicated to particular forms of the god, "Coptite Osiris", "Osiris Ounennefer at the heart of the tree (iched)”, “Osiris sovereign of eternity”, etc. The Osirian tomb of Karnak is marked by three successive phases, the architecture tending to become more complicated over time.

At the end of the New Kingdom, the figurines were buried in small individual mudbrick tombs. These miniature structures are juxtaposed or superimposed on each other, without any coherent order.

During the Saite Period and the Late Period , the system of miniature tombs continued, but they were installed inside a construction made up of vaulted chambers built against each other, as they were filled. The era of this architectural system is dated by bricks stamped with the name of Nékao II, a pharaoh from the end of the 7th century BC. Fragile fragments of plaster figurines were discovered inside. These effigies take the form of mummified Osiris. This tomb must have been partially buried, but the two largest vaulted chambers were accessible through two small arched doors. The whole thing had to be covered by an artificial mound planted with one or more trees.[74][75]

- Remains of the Theban Osireion (Saite tomb)

-

Vaulted chambers of the Osirian tomb.

-

Close-up of the tomb.

Under the reign of Ptolemy IV, a building was built which took the form of vast catacombs with a rational organization. The tomb is organized around three vaulted galleries, each of which includes miniature vaults (a sort of wall niches) spread over four levels. The capacity of these catacombs is estimated at a total of 720 vaults.[76][77]

- Remains of the Theban Osireion (Ptolemaic catacombs)

-

View of the remaining niches in the catacombs of Ptolemy IV.

Oxyrhynchos[edit]

Located in the ancient 19th century of Upper Egypt, the city of Oxyrhynchus (Oxyrhynchos) (in Egyptian Per-Madjaj , in Coptic Pemdjé , in Arabic El-Bahnasa ) is rich in remains dating from the Pharaonic and Greco-Roman eras . Since the years 2000-2001, a Hispano-Egyptian mission has endeavored to excavate the site of the local Osiréion , known by the Egyptian name of Per-Khef. The sanctuary appears as a 3.50 meter high mound isolated in the desert. On the surface, all that remains is a leveled, square structure, fifteen meters on a side. A brick surrounding wall demarcated a rectangular sacred space 165 meters long by 105 meters wide, where a small sacred lake had been dug in the northern corner.

The underground structures of the sanctuary were dug into the rock of the Jebel. They are accessible by three staircases including a main staircase which opens into a vestibule. The latter leads to two rooms about ten meters long. The first was found empty. In the second, there lay a large limestone statue of Osiris, made to be lying down because, with its 3.50 meters high, it would not have been able to stand erect under the vault. From this room two long galleries run east-west. These corridors were dug into the rock and their walls were masoned with blocks of white limestone imported from another locality. The north and south walls are punctuated with symmetrical niches of the same size. As the site was looted, the sacred figurines were no longer in their niches, but were broken and scattered in the rubble. Only one was found intact in its individual tomb; it was molded from silt mixed with bitumen and barley grains. It was then wrapped in linen strips. The broken figurines differ in size and appearance, some are ithyphallic , others, smaller, are sheathed in yellow stucco with a fishnet painted on the body. It seems that each figurine benefited from a funerary trousseau composed of the four children of Horus (molded figurines), a miniature offering table, fruit offerings and protective amulets, pellets or cones, dedicated to dangerous goddesses. Above each niche is an inscription giving the year of burial with mentions of Ptolemaic kings. Gathering all the archaeological data, we know that the sanctuary was used from the 26th Dynasty until the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian.[78][79]

Coptos[edit]

In 1904, a pink granite tank was released by chance by workers during digging on the site of ancient Qift. Since then, the vat has been kept at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo where it is exhibited (reference no. JE37516). The dimensions of this artifact and the texts engraved on it show that it is a large garden vat intended for the ritual manufacture of an Osirian figurine during the month of Khoiak. This object constitutes a testimony to the worship paid by the priests of Coptos around 850 BC to Osiris. A scene from the setting shows the Theban pharaoh Harsiesi A (22nd dynasty) offering earth and barley to Osiris-Khentymentyou and Chentayt of Abydos. On another scene his son, Prince Amonrasonter, is shown performing incenses and lustrations before Osiris-Khentymentyou and Chentayt of Bousiris. The text is very degraded in places but it seems to be taken from a ritual specific to the town of Bousiris where, from the twelve to the twenty-fourth Khoiak, barley was ceremonially germinated. In 1977, these texts were examined by Jean Yoyotte. From certain graphic uses, it appears that this ritual basin preserves texts composed before the New Kingdom, a time when the gods Osiris and Sekeris were not yet assimilated. Among the texts are two poems where the goddess Chentayt is much closer to Hathor than to Isis, another proof of the antiquity of the composition.[80]

Calendar of Mysteries for the month of Khoiak[edit]

The Ritual of the Mysteries of Osiris , preserved by the temple of Dendera, is more of an archive, a witness to the rites, than a true calendar of Khoiak ceremonies. The indications provided contradict each other, intersect and appear different from one holy city to another. It is likely that certain acts are passed over in silence, because certain days are not even mentioned, such as the 13th, 17th, 26th, 27th, 28th and 29th of the month. It is therefore quite difficult to draw up a complete and rigorous chronological order of operations. Despite these difficulties, certain facts appear clearly established .[81][82]

Khoiak 12 Day[edit]

The Mysteries dedicated to the god Osiris begin on Khoiak 12 and last nineteen days until the end of the month. In several places in the Denderah text the celebration takes the name of festival (deni) (also known as “Quarter Moon Festival”), the rituals are therefore compared with the lunar phase; the festival (deni) being moreover the seventh day of each lunar month. At the fourth hour of day,[Note 14] the officiants prepare barley and sand intended to form the figurines of the Kentymentiou and the “Divine Lambeau”. After being measured, the ingredients are mixed and placed in gold molds. Everything is placed in a garden tank, between two layers of rushes. The mixture of soil and barley is watered every day until Khoiak 21 to allow the seeds to germinate.[81][83]

“As for what is done in Busiris, it is carried out on the twelfth Khoiak, in the presence of Chentayt who takes his place in Busiris, with barley, 1 hin,[Unit 3] and sand, four hin , by means of a golden situla, next to Chentayt, reciting over it the formulas of “Pour water on the humors”. The protective gods of the garden tank protect it until the 21st of Khoiak comes.” — Ritual of the Mysteries , Book II , col. 19-20. Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville.[84]

Day of Khoiak 12 or 14[edit]

The twelve Khoiak, at the third hour of the day (Book VI , 116) or two days later, the fourteenth (Book III , 35 and Book V , 88-89), begins the preparation of the sacred dough used to make the figurine from Seker.[Note 15] Priests, disguised as Anubis and under the patronage of a statue of Chentayt (Isis), weigh and mix the various ingredients prescribed by the texts. The collection sets out three recipes (Book III , 33-35; Book VI , 117-121 and Book VII , 135-144). The base of the preparation consists of earth, date pulp, myrrh, incense, herbs, pulverized precious stones and water drawn from the sacred lake of the temple. These materials are worked to give everything the shape of an egg. This ball is then covered with sycamore branches so that it remains ductile and humid. It is placed in a silver vase until the sixteenth of the month.[85]

“As for the fourteenth of Khoiak, a great processional festival in the Athribite nome, in the city called Iriheb, the contents of the mold of Seker are made on this day with the contents of the venerable vase, which is why the mummy is called composite mummy. This compound of this god is started by the swaddler in the athribite nome on this day. There are four priests for this in Busiris, in the Sanctuary of Chentayt, they are four gods of the embalming workshop of Heliopolis. — Ritual of the mysteries , Book V , col. 88-89. Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville.[86]

Khoiak Fifteenth Day[edit]

On the fifteenth of Khoiak, the decoration of the neb ânkh ("master of life") sarcophagus intended for the Seker figurine of the previous year which had been kept in a room of the temple during the past year is carried out. At the end of the month, this figurine is permanently buried in a necropolis. The coffin is made of sycamore wood, one cubit two palms long (67.20 cm) by three palms two fingers wide (26.30 cm). It takes the form of a mummy with a human head, arms crossed on the chest and holding the crook and the whip. [87]An inscription is engraved and painted in a dark green color to indicate the royal title of Osiris: “The Horus who stops the massacre in the Two Lands, king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Osiris, master of Busiris, he who presides over the West, great god, master of Abydos, master of the sky, of the earth, of the infernal world, of water, of the mountains, of the whole orb of the sun” (Book V, 42- 43).[88]

“We bring the sarcophagus; divine matter is applied to it for dyeing; we make our eyes with colors and our hair with lapis lazuli. — Ritual of the Mysteries , Book VII , col. 146. Translation of Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville.[89]

While the Seker figurine is being cast, another coffin is being made, in Cedrus wood, where it will be placed on the twenty-fourth Khoiak. The same day, the preparation of mereh shepes (“the venerable ointment”) begins, which requires cooking between the eighteenth and twenty-second of the month: “On the 15th day , mix the ointment; the 18th , cook; the 19th , cook; on the 20th , cook; the 21st , cook; on the 22nd , remove it from the fire. The Denderah collection only gives this ointment its main ingredient, asphalt. The other substances are, however, known thanks to an inscription from the temple of Edfu: pitch, lotus essence, incense, wax, terebinth resin and aromatics.[90][91]

Sixteenth Khoiak Day[edit]

First procession of the Opening of the Sanctuary[edit]

On the sixteenth of Khoiak, probably between the first and third hours of the day, the funeral festival of Oun per takes place , literally “Opening of the House” or more precisely “Opening of the Sanctuary”. The sacred dough intended to produce the new Seker is taken in procession in the temple, through the cemetery where all the old figurines rest and in the “Valley” that is to say the local necropolis.[92] The vase which contains this material is placed in the atourit , a reliquary chest in gilded wood 78 cm long by 36 cm wide, topped with a statuette of Anubis as a lying jackal. This chest is transported in a small sacred boat 183 cm long provided with four stretchers to allow it to be carried in the arms of men (Book V, 82-83)[93]:

“At the Opening of the sanctuary, he goes out with guardian Anubis […] the sixteenth and twenty-fourth Khoiak. He walks through the temple of the divine necropolis; he enters and travels through the valley. There are four obelisks of the divine shrine of the Children of Horus in front of him, as well as the ensign gods.[Note 16] — Ritual of the mysteries, Book V , col. 82-83. Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville.[94]

Casting of the Seker[edit]

Later, at the third hour of the day, in the temple, a priest with a shaved head takes the silver vase where, since the twelve (or fourteen) Khoiak, the ball of dough used to make the Seker figurine rested . The vase is placed on the lap of a statue of Nut, the celestial goddess considered to be the mother of Osiris. The two pieces of the gold mold of the Seker are brought and placed on the ground on a rush mat. The mold is brushed with oil and the sacred dough is poured inside. Once the mold is filled and closed, it is placed on a sheltered bed in a covered pavilion until the nineteenth of the month (Book VI , 121-125).[95]

"Then a shorn priest sits on a stool of moringa wood, in front of her, covered with a panther's skin, with a loop of real lapis lazuli on his head. This vase is placed on his hands, and he says: “I am Horus who comes to you, Mighty One, I bring you these things from my father. We place the vase on the knees of the Great One who gives birth to the gods, then we bring the mold of Seker […] Anoint her body with sweet moringa oil. We place the contents of this vase inside. While the front part of the mold is on the ground, on a rush mat, the contents of this vase are placed there and the rear part of the mold is placed on it." — Ritual of the Mysteries , Book VI , col. 122-124 (extracts). Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville .[96]

Days from the sixteenth to the nineteenth Khoiak[edit]

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth Khoiak, the symbolic reconstitution of the dismembered body of Osiris takes place. In a room of the temple, the mold of the Seker filled with its sacred paste rests on a golden funeral bed measuring one cubit two palms in length (67 cm ), the head turned towards the north. The threshold of the room is guarded by two statuettes of Hu and Sia, personifications of the word and the omniscience of the creator god Atum-Re. The bed is placed in the heneket nemmyt room, 1.57 m long, 1.05 m wide and 1.83 m high, made with black ebony wood plated with gold. This room is itself placed under a rectangular pavilion comprising fourteen wooden columns linked together by papyrus mats [97]:

“As for the canvas-covered pavilion, it is made of coniferous wood and consists of fourteen columns erected on the ground, the top and base of which are made of bronze. A covering of papyrus mats and plants surrounds it. Its length is seven cubits (= 367.5 cm), its width, three 1/2 cubits (= 183.75 cm), its height, eight cubits (= 420 cm). It is covered with fabric on the inside." — Ritual of the Mysteries , Book VI , col. 69-71. Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville 96 .[98]

Khoiak Nineteenth Day[edit]

On the nineteenth of Khoiak, at the third hour of the day, the Seker figurine came out of the mold in which it had rested since the sixteenth of the month. In order to dry and harden it perfectly, it is placed until the twenty-third of the month on a base, in full sun. However, so that it does not crack, it is regularly anointed with perfumed water[95]:

“We then remove this god from inside the mold, we place him on a gold base. It is exposed to the sun and anointed with dry myrrh and water every day until the twenty-third Khoiak comes." — Ritual of the Mysteries , Book VII , col. 125-126. Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville.[96]

Night of the twenty-first Khoiak[edit]

On the twentieth of Khoiak, at the eighth hour of the night, the weaving of a piece of fabric intended to serve as funeral linen for the sacred figurines begins. The work continues for a whole day and ends the next day, the twenty-first, at the same time[95]:

“As for the piece of one-day cloth, it is made from the twenty-first to the twenty-first Khoiak, which is twenty-four hours to work on it, from the eighth hour of the night to the eighth hour of the night. Its length is nine 1/3 cubits (= 490 cm), its width is three cubits (= 157.5 cm) […] As for the rope for binding the jersey, it is made with the piece of fabric d 'one day, just like the linen shroud of the two companions" — Ritual of the mysteries , Book V , col. 50-52. Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville.[99]

Twenty-first Khoiak Day[edit]

Unmolding the Khenti-Amentiu[edit]

Since the twelfth of the month, to shape the Khenti-Amentiu figurine , a mixture of sand and barley rested in a mold made of two gold pieces. The soil was watered every day to cause the seeds to germinate. On the twenty-first Khoiak, once the young shoots have appeared, the two side parts of the figurine are unmolded. The two blocks thus formed are then joined using an incense-based resin and four cords. Everything is left to dry in the sun until the fifth hour of the day. The same is done for the “Divine Lambeau” which rested in the same garden vat as the Khenti-Amentiu.[100]

“We remove this god from the inside of the mold on this day and we put dry myrrh, a deben, on each of the parts of which it is composed. Place the two sides on top of each other. Bind with four cords of papyrus, namely: one to his throat, the other to his legs, one to his heart, the other to the ball of his white crown, according to this model. Expose it to the sun all day." — Ritual of the Mysteries , Book VI , col. 111-113. Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville.[101]

Funerary cloth from Seker[edit]

The twenty-first Khoiak is the day when a piece of fabric[Note 17] is woven to provide the Seker figurine with its funerary linen.[102] This funerary linen is symbolically linked to the ideal duration of human mummification established, according to Herodotus, at exactly seventy days, a duration modeled on that of the embalming by Anubis of the dismembered body of Osiris.[Note 18] During this period, the corpse rested in a bath of natron then was washed and wrapped in strips:

“As for the twenty-first Khoiak, it is the day of doing the work of the cloth of a day, because it is the fiftieth day of the embalming workshop, a day counting as ten, and because we make one day's worth of the fifty days of the embalming workshop." — Ritual of the mysteries , Book V , col. 93. Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville.[86]

The mummification of the Seker extends symbolically between the sixteenth Khoiak (putting the sacred paste into the mold) and the twenty-third Khoiak (end of drying of the figurine unmolded on the nineteenth), i.e. a duration of seven days corresponding to the sixty -ten days attributed to the consolidation of the body of Osiris (7 x 10 = 70). The twenty-first day, the fifth of the Khoiak ritual process, is therefore related to the fiftieth day (5 x 10 = 50).[103]

Twenty-second Khoiak Day[edit]

On the twenty-second Khoiak, at the eighth hour of the day, a nautical procession takes place on the sacred lake located within the temple grounds. This celebration involves thirty-four papyrus boats, models one cubit two palms long (67 cm ) which transport the statues of the gods Horus, Thoth, Anubis, Isis, Nephthys, those of the four children of Horus and those of twenty-nine other minor deities. The flotilla is illuminated with a total of three hundred and sixty-five lamps which symbolize the days of the year. The text of the Ritual of the Mysteries does not expressly mention it, but it is possible that this navigation aims to reenact the funeral procession of Osiris through the presence on a boat of the plant figurine of the Khentymentyou; the passage over the water marks the god's entry into the world of the deceased. At the end of the navigation, the divine statues are wrapped in fabrics and placed in the Shentyt , the “mysterious chapel”, in fact a room of the temple dedicated to the Osirian mysteries and where the figurine of Seker is kept for a year. The list of gods participating in navigation is mentioned in Book III (columns 73-78) but is however incomplete due to the ravages of time.[104]

“To sail them on the twenty-second Khoiak, at the eighth hour of the day. There are many lamps beside them, as well as the gods who guard them, each god being designated by name […] This applies to the thirty-four boats alike." — Ritual of the Mysteries , Book II , col. 20-21. Translation by Émile Chassinat reviewed by Sylvie Cauville.[84]

Days from twenty-two to twenty-six Khoiak[edit]