National Malaria Eradication Program

In the United States, the National Malaria Eradication Program (NMEP) was launched in July 1947. By 1951 this federal program—with state and local participation—had reduced the incidence of malaria in the United States to the point that the program was officially ended.[1]

History

[edit]Malaria was originally only endemic in the Old World. Plasmodium vivax was imported to North America by British settlers, and Plasmodium falciparum arrived in the bodies of enslaved Africans.[2] The expansion of agriculture in the North often involved clearing forests and draining swamps, reducing the breeding area for mosquitoes. The opposite happened in parts of the South, as the breeding area increased where rice was grown.[3]

The 1890 US census reported 880 thousand deaths, of which 2.1 percent were due to malaria. This percentage ranged from 0.2 percent in Minnesota and Wyoming to 10.6 percent in Arkansas; see the accompanying figure.[4]

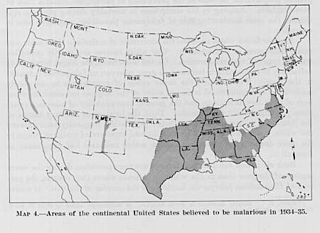

By the 1930s, malaria had become concentrated in 13 southeastern states. In 1940 the United States Department of War asked the Public Health Service (PHS) to help organize public health activities near military facilities, most of which were in the South. In the spring of 1941 the PHS assigned its chief malariologist, Louis L. Williams, Jr., as liaison officer to the Fourth Service Command's headquarters in Atlanta. Early in 1942 the PHS obtained funds for an independent malarial control program for military installations and war industries in 15 southeastern states and the Caribbean. This program was called Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA). It was led by Williams in Atlanta. The program focused primarily on larvicide. They started with Paris green. However, diesel oil soon became the primary larvicide. That was replaced by DDT starting in 1944.[5]

From its beginning in 1942, this was a cooperative undertaking by federal, state and local health agencies. The CDC's first director, Justin M. Andrews, was also Georgia's chief malariologist. Its headquarters were in Atlanta, in part because malaria was locally endemic. Offices were located on the sixth floor of the Volunteer Building on Peachtree Street. With an annual budget of about $1 million, some 59% of its personnel were engaged in mosquito abatement and habitat control.[6] Among its 369 employees, the main jobs at CDC at this time were entomology and engineering.[citation needed]

In 1945 a former US Public Health Service Research Hospital on Oatland Island, near Savannah Georgia was turned into a large MCWA Research Facility. The Oatland Research Facility conducted research on a variety of diseases, including insect and airborne diseases, and developed methods for controlling and preventing the spread of these diseases. One notable achievement of the CDC lab on Oatland Island was the development of the "No-Pest Strip," which was invented at the laboratory and later led to the development of the flea collar. It closed and consolidated with the Atlanta offices in 1973.[7]

In 1946, there were only seven medical officers on duty and an early organization chart was drawn, somewhat fancifully, in the shape of a mosquito.[8] That same year, Joseph Mountin, head of the State Relations Division of the PHS, which included MCWA, obtained the support of the National Institutes of Health for the creation of a Communicable Disease Center (CDC), built on the MCWA. That became the National Communicable Disease Center in 1967, the Center for Disease Control in 1970, the Centers (plural) for Disease Control in 1980 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1992.[5]

During the CDC's first few years, more than 6,500,000 homes were sprayed with the insecticide DDT. DDT was applied to the interior surfaces of rural homes or entire premises in counties where malaria was reported to have been prevalent in recent years. In addition, wetland drainage, removal of mosquito breeding sites, and DDT spraying (occasionally from aircraft) were all pursued. In 1947, some 15,000 malaria cases were reported. By the end of 1949, over 4,650,000 housespray applications had been made and the United States was declared free of malaria as a significant public health problem. By 1950, only 2,000 cases were reported. By 1951, malaria was considered eliminated altogether from the country and the CDC gradually withdrew from active participation in the operational phases of the program, shifting its interest to surveillance. In 1952, CDC participation in eradication operations ceased altogether.[citation needed]

A major international effort along the lines of the NMEP—the Global Malaria Eradication Programme (1955–1969), administered by the World Health Organization—was unsuccessful.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations and notes

[edit]- ^ Horton, Richard (2011), "Stopping Malaria: The Wrong Road", The New York Review of Books, 24 February issue.

- ^ Meade and Emch (2010, p. 119)

- ^ Melinda S. Meade; Michael Emch (2010). Medical Geography, 3rd ed. Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-60623-016-9. OL 23919657M. Wikidata Q108477842..

- ^ John Shaw Billings (1894), Report on the Vital and Social Statistics in the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890. Part III. -- Statistics of Deaths (PDF), United States Government Publishing Office, Wikidata Q108475883

- ^ a b John Parascandola (1 November 1996). "From MCWA to CDC--origins of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention" (PDF). Public Health Reports. 111 (6): 549–551. ISSN 0033-3549. PMC 1381908. PMID 8955706. Wikidata Q24541298..

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The History of Malaria, an Ancient Disease, Atlanta, GA, 2004.

- ^ "Our History". Oatland Island Wildlife Center. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ "Our History - Our Story". About CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 26 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015.

Other sources

[edit]- Humphreys, Margaret (2001), Malaria: Poverty, Race, and Public Health in the United States, Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Daniel Sledge and George Mohler (2013), "Eliminating Malaria in the American South," American Journal of Public Health.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010), “Elimination of Malaria in the United States (1947–1951)”.

- Malaria organizations

- Medical and health organizations based in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Organizations established in 1947

- Organizations based in Atlanta

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- 1947 establishments in the United States

- 1952 disestablishments in the United States

- Organizations based in DeKalb County, Georgia

- Public health organizations

- Organizations disestablished in 1952