Neil Goldschmidt

Neil Goldschmidt | |

|---|---|

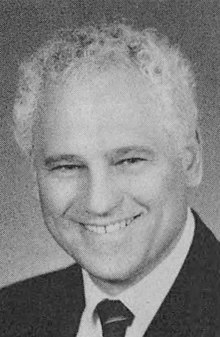

Goldschmidt in 1986 | |

| 33rd Governor of Oregon | |

| In office January 12, 1987 – January 14, 1991 | |

| Preceded by | Victor Atiyeh |

| Succeeded by | Barbara Roberts |

| 6th United States Secretary of Transportation | |

| In office September 24, 1979 – January 20, 1981 | |

| President | Jimmy Carter |

| Preceded by | Brock Adams |

| Succeeded by | Drew Lewis |

| 45th Mayor of Portland | |

| In office January 2, 1973 – August 15, 1979 | |

| Preceded by | Terry Schrunk |

| Succeeded by | Connie McCready |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 16, 1940 Eugene, Oregon, U.S. |

| Died | June 12, 2024 (aged 83) Portland, Oregon, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Margaret Wood

(m. 1965; div. 1990)Diana Snowden (m. 1994) |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | University of Oregon (BA) University of California, Berkeley (JD) |

Neil Edward Goldschmidt (June 16, 1940 – June 12, 2024) was an American businessman and Democratic politician from the state of Oregon who held local, state, and federal offices over three decades. After serving as the United States Secretary of Transportation under President Jimmy Carter and governor of Oregon, Goldschmidt was at one time considered the most powerful and influential figure in Oregon's politics. His career and legacy were severely damaged in 2004 by revelations that he raped a young teenage girl in 1973, during his first term as mayor of Portland.[1][2][3]

Goldschmidt was elected to the Portland City Council in 1970 and then as mayor of Portland in 1972, becoming the youngest mayor of any major American city. He promoted the revitalization of Downtown Portland and was influential on Portland-area transportation policy, particularly with the scrapping of the controversial Mount Hood Freeway and the establishment of the MAX Light Rail system. He was appointed U.S. Secretary of Transportation by President Jimmy Carter in 1979; in that capacity he worked to revive the ailing automobile industry and to deregulate several industries. He served until the end of Carter's presidency in 1981 and then served as a senior executive with Nike for several years.

In 1986, Goldschmidt was elected the 33rd governor of Oregon, serving a single term. He faced significant challenges, particularly a rising anti-tax movement (leading to Measure 5 in 1990) and a doubling of the state's prison population. He worked across party lines to reduce regulation and to repair the state's infrastructure. His reforms to the State Accident Insurance Fund (SAIF), a state-chartered worker's compensation insurance company were heralded at the time, but drew strong criticism in later years.

Despite his popularity, Goldschmidt did not seek a second term as governor, becoming an influential and controversial lobbyist. Over the next dozen years or so, he was criticized by editorial boards and Oregonians for several of the causes he supported, including backing the forestry corporation Weyerhaeuser in its hostile takeover of Oregon's Willamette Industries and his advocacy for a private investment firm in its attempt to take over utility company Portland General Electric. In 2003, Governor Ted Kulongoski appointed Goldschmidt to the Oregon Board of Higher Education, a position he resigned after admitting he had sexually abused a minor girl 30 years earlier.

Early life[edit]

Goldschmidt was born in Eugene, in Oregon's Willamette Valley, on June 16, 1940,[4] into a Jewish family to Lester H. Goldschmidt and Annette Levin.[5] He graduated from South Eugene High School.[5] He later attended the University of Oregon, also in Eugene. He served as student body president at the school before graduating in 1963 with a bachelor's degree in political science.[6]

Goldschmidt earned a Juris Doctor from the University of California, Berkeley in 1967.[6] From 1967 to 1970, he worked as a legal aid lawyer in Portland, Oregon.[4] Goldschmidt served as an intern for U.S. Senator Maurine Neuberger in 1964 in Washington, D.C.[5] While there, he was recruited by New York Congressman Allard K. Lowenstein to register voters in Mississippi's 1964 Freedom Summer civil rights campaign.[5]

Political career[edit]

Portland City Commissioner and Mayor[edit]

Goldschmidt won a seat on the Portland City Council in 1970.[4] As City Commissioner (1971–1973) and later as Mayor of Portland (1973–1979), Goldschmidt participated in the revitalization of the downtown section of that city. He led a freeway revolt against the unpopular Mount Hood Freeway, building consensus among labor unions and other powerful entities to divert Federal funds initially earmarked for the freeway to other projects, ultimately expanding the federal funds brought to the region to include the MAX Light Rail line and the Portland Transit Mall.[7] He is widely credited with having opened up the city's government to neighborhood activists and minorities, appointing women and African-Americans in a City Hall that had been dominated by an "old-boy network".[8] During his mayoral campaign, he questioned the benefit of expanding the city's police force, preferring to direct resources to crime prevention.[9] According to Nigel Jaquiss, a reporter for Willamette Week, for thirty years he was "Oregon's most successful and charismatic leader".[10]

In 1973, Governor Tom McCall appointed Goldschmidt to what would be known as the Governor's Task Force, which was tasked with exploring regional transportation solutions.[11] Goldschmidt served alongside notable leaders: Glenn Jackson, chair of the board of Portland Power and Light and chair of the Oregon Transportation Commission, was considered the state's leading power broker on transportation issues; and Gerard Drummond, a prominent lawyer and lobbyist, was president of Tri-Met's board of directors.[11] The task force considered an unpopular deal that would have funded the construction of the Mount Hood Freeway, which would have bisected southeast Portland.[11] The deal, which would have been 90% funded by the Federal Highway Administration, was rescinded, with first the Multnomah County Commission and, later, Portland City Council reversing their positions and advising against it. Goldschmidt was initially opposed to diverting funds to light rail, instead favoring busways and more suitable local road projects; as the 1981 deadline to reallocate the funds approached, however, light rail became a more attractive prospect. By a process not clearly documented, light rail was included in the final plan. All federal money initially intended for the Mount Hood Freeway ultimately went to other road projects, but the total amount was doubled and the first leg of MAX light rail was approved and ultimately completed in 1986.[11]

U.S. Secretary of Transportation[edit]

Goldschmidt became the sixth U.S. Secretary of Transportation in 1979. His recess appointment by President Jimmy Carter came on July 27 of that year, as part of a midterm restructuring of the Carter administration's cabinet positions.[12] The United States Senate confirmed his appointment on September 21, and he was sworn in on September 24.[13] In this position, Goldschmidt was known for his work to revive the financially ailing U.S. auto industry,[14] and efforts to deregulate the airline, trucking, and railroad industries.[4]

A newcomer to the Carter administration and to national politics, Goldschmidt traded not only on his experience in transportation planning, but on his political acumen as well; following Carter's unsuccessful bid for re-election in 1980, Goldschmidt expressed doubts about the future of the Democratic Party if it couldn't learn to cultivate political allies more effectively.[15] Goldschmidt's time in Washington, DC, informed his own understanding of politics, as well.[16] He remained in office through the remainder of the Carter administration. In late 1979, Republican presidential hopeful John B. Anderson called for Goldschmidt's resignation, and members of the United States Senate Banking Committee later chastised him,[17] for having suggested that he would withhold transportation funds from municipalities, such as Chicago and Philadelphia, whose mayors supported Ted Kennedy in his primary election bid against Carter.[12] Goldschmidt resigned at the conclusion of Carter's term on January 20, 1981.[18]

Between positions in public office, Goldschmidt was a Nike executive during the 1980s,[19] serving as international Vice President and then as president of Nike Canada.[4] He was considered as a potential chair of the Democratic National Committee in 1984.[20]

Governor of Oregon[edit]

In June 1985 Goldschmidt announced his candidacy for Governor of Oregon. His name familiarity and access to large donations through his business and political ties made him the Democratic front runner. He defeated Oregon State Senator Edward Fadeley in the May 1986 Democratic primary. Goldschmidt defeated Republican Secretary of State Norma Paulus in the 1986 general election 52% to 48%, succeeding two-term Republican Governor Victor Atiyeh,[21] becoming the state's 33rd governor.

Goldschmidt's policy for economic development brought together Democratic liberals and Republican business leaders. His personal focus was on children's rights, poverty, and crime, but the challenge of meeting increasing needs with a decreasing budget overshadowed his tenure. An anti-tax movement took hold during his term, passing the landmark Measure 5 in 1990, which restricted the generation of revenue by property tax.[22] He was credited with leading "The Oregon Comeback", bringing the state out of nearly eight years of recession, through regulatory reform and repair of the state's infrastructure.[4]

Goldschmidt oversaw a major expansion of the state's prison system. In May 1987, he hired Michael Francke to modernize the state's prisons, which an investigator had described as overcrowded and operated as "independent fiefdoms".[23] Francke was charged with supervising a plan to add over 1000 new beds to the prison system.[24] Francke was murdered in the Department of Corrections parking lot in 1989.[24]

In 1990, Goldschmidt brokered agreements between business, labor, and insurance interests that changed the state's workers' compensation regulations. Workers' compensation has been a contentious issue in Oregon for some time, as the state-run State Accident Insurance Fund (SAIF) insures approximately 35% of the workforce. The legislature passed a law as a result. The changes were considered to benefit the insurance industry and business interests, at the expense of claimants, who were required to establish more extensively that their employers were responsible for injuries. The issue was contentious for some time, involving lawsuits and various efforts to modify the law.[25] In 2000, Governor John Kitzhaber attempted to reform the system again. This led to a new law in the 2001 Legislature, which was complicated by an Oregon Supreme Court ruling that occurred during deliberations.[26][27]

Goldschmidt's Children's Agenda was important in Oregon with its community initiatives.[22] In 1991, he helped create the Oregon Children's Foundation, as well as the Start Making A Reader Today (SMART) literacy program, which puts 10,000 volunteers into Oregon schools to read to children.[28]

Goldschmidt declined to run for re-election in 1990, despite the widely held perception that he could have been easily re-elected; at the time, he cited marital difficulties.[29] Bernie Giusto, who was Goldschmidt's driver at the start of his term and later became Multnomah County Sheriff, was widely rumored to be romantically involved with Goldschmidt's wife Margie (and later dated her openly after the Goldschmidts' divorce).[30]

Goldschmidt had hoped at one time to serve two terms, noting that most of predecessor Tom McCall's accomplishments came during his second term.[22] In his farewell address to the City Club of Portland, he stated: "After only four years, everything is left undone. Nothing is finished."[22]

After leaving elected office[edit]

Goldschmidt founded a law and consulting firm, Neil Goldschmidt, Inc., in Portland in 1991, four days after leaving office as governor.[31] Even out of elected office, he was widely considered the most powerful political figure in the state for many years. His influence extended all over the state and the nation. As a member of the Oregon Health & Science University board, Goldschmidt was an early advocate of the controversial Portland Aerial Tram, which connected the research hospital to real estate projects by his longtime associates Homer Williams and Irving Levin near land whose owners Goldschmidt later represented.[32][33] He stayed active in Portland as well, advocating an expansion of the Park Blocks (a strip of open park space cutting through downtown Portland.)[34] Goldschmidt assisted in the deal that led to the construction of TriMet's MAX Red Line to Portland International Airport that opened in 2001.[35] He also started the Start Making a Reader Today (SMART) volunteer program in Oregon schools.[35]

Goldschmidt drew criticism in recent years for some of his business activities. In 2002, he lobbied business and political leaders to support Weyerhaeuser in its hostile takeover of Willamette Industries, Inc., then the only Fortune 500 company headquartered in Portland.[35] In early 2004, he backed a purchase of Portland General Electric (PGE) by Texas Pacific Group which, though never consummated, put on hold city and county studies to acquire PGE by condemnation. Criticism of Goldschmidt's business activities peaked when, on November 13, 2003, Governor Ted Kulongoski nominated him to the Oregon State Board of Higher Education.[36]

Goldschmidt's appointment was initially expected to meet with little opposition. Several state senators, however, voiced concerns about Goldschmidt's involvement with SAIF and possible improprieties in the dealings he and his wife had with Texas Pacific.[37][38] Senator Vicki Walker, in particular, emerged as an outspoken critic of Goldschmidt.[39][40]

Revelation of sexual abuse[edit]

The increased scrutiny on Goldschmidt's career, including reporters' difficulties accessing records from his time as governor,[41] ultimately led to the revelation of his years-long sexual abuse of a minor girl, which had occurred decades before, during his time as Mayor of Portland. These revelations ended Goldschmidt's extensive career at the center of Oregon politics and policymaking. In May 2004, a rapid series of events resulted in Goldschmidt's confession to repeatedly raping a young teenage girl in the mid-1970s; the quick demise of his political career, including resignations from several prominent organizations; and the transfer of his many documents from the privately run Oregon Historical Society to the state-run Oregon State Archives.[42]

On May 6, under pressure from Willamette Week, Goldschmidt publicly announced that he had repeatedly raped a 14-year-old girl (the victim later indicated she was 13)[43] for an extended period during his first term as Mayor of Portland.[2] Sex with a person under 16 years of age constitutes third degree rape under Oregon law, a felony punishable by up to five years in prison.[44][45] By the time the abuse had become public, however, the statute of limitations of three years had expired, making Goldschmidt immune from any prosecution over the matter.[46]

Goldschmidt's confessional letter was published on the front page of The Oregonian on May 7, 2004.[47] It differed from the Willamette Week's account, most notably in the length of the abuse ("nearly a year" according to Goldschmidt, but three years according to Willamette Week at the time; it was later revealed by Willamette Week that the abuse actually continued through 1991, after Goldschmidt's single term as governor) and in Goldschmidt's use of the term "affair" to characterize it. The Oregonian was criticized for its coverage and use of the term "affair". Writers and editors at The Oregonian acknowledged mistakes in their handling of the story, but denied that a desire to protect Goldschmidt motivated the mistakes.[1] The Willamette Week article, written by Nigel Jaquiss, was awarded the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting.[48]

In his initial negotiations with Willamette Week, Goldschmidt agreed to resign his positions with the Texas Pacific Group and the Board of Higher Education, which he did.[1] His decision in 1990 not to run for a second term as governor, long the subject of speculation,[31] was finally explained.[49] Further developments revealed that Goldschmidt was assisted by businessman Robert K. Burtchaell in keeping his molestation of the girl a secret. In return, Goldschmidt gave his support to Burtchaell's (unsuccessful) bid to extend a lease for a houseboat moorage on the Willamette River.[50]

Goldschmidt's rabbi made an appeal in The Oregonian for forgiveness. Although Goldschmidt could no longer be prosecuted for the offense, the Oregon State Bar began an investigation into the matter. Goldschmidt submitted a Form B resignation, which was received by the bar on May 13, and rendered him ineligible for readmission.[49][51]

Following complaints from local media over limited access to Goldschmidt's public papers stored at the Oregon Historical Society (OHS),[52] the state archivist announced May 29 that Goldschmidt would seize the 256 boxes of documents to guarantee public access as defined in a state law passed in 1973. That law required that public access to such records be maintained, but did not specify where the records be kept.[53] Following Goldschmidt's decision to put the documents in the care of the OHS, the state legislature passed a law requiring future governors to leave their documents in the state archives.[53] Many records were published on the state archives' website[54] in early 2005.[55]

The scandal has affected numerous people and organizations associated with Goldschmidt. Many people have been accused of knowing of the crime, but failing to act accordingly. Debby Kennedy, who worked for Goldschmidt while he was governor, recalled, "I just can't tell you how many rumors there were about him then."[56] Multnomah County Sheriff Bernie Giusto, who admitted knowing about the abuse,[56] announced his early retirement in February 2008.[57]

On March 7, 2011, the Oregon Senate President and Co-Speakers of the House released a statement that Goldschmidt's Governor's portrait had been removed from the walls of the State Capitol building in Salem and put into storage, out of respect for his victim, Elizabeth Lynn Dunham, who died from cancer on January 16, 2011, at the age of 49.[58]

Personal life[edit]

Goldschmidt married Margaret Wood in 1965. They had two children, Joshua and Rebecca, and divorced in 1990.[6] Around the time he started his consulting firm, he met his second wife, Diana Snowden, who worked for PacifiCorp as a senior vice president.[59]

Goldschmidt died from heart failure at his home in Portland, on June 12, 2024, at the age of 83.[60]

Publications by Goldschmidt[edit]

- Goldschmidt, Neil (January 1981). The U.S. Automobile Industry, 1980. Report to the President from the Secretary of Transportation (Report). United States Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- Goldschmidt, Neil (January 21, 1981). "The Last Hurrah". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- Goldschmidt, Neil (March 25, 1990). "As Highways Crumble, Bush Stumbles". Opinion. The New York Times. Section 4, p. 19. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- Goldschmidt, Neil (May 7, 2004). "Statement by Neil Goldschmidt". The Oregonian. Portland, OR. p. A01. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Rosen, Jill (August–September 2004). "The Story Behind the Story". American Journalism Review. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2006.

- ^ a b Jaquiss, Nigel; John Schrag (May 12, 2004). "The 30-Year Secret – A crime, a cover-up and the way it shaped Oregon". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ Howard Kurtz (May 13, 2004). "Another Abuse Story". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Biography of Oregon political icon Neil Goldschmidt". KGW News. May 6, 2004. Archived from the original on February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Governor Neil Goldschmidt's Administration: Biographical Note". Oregon State Archives. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c Neil Goldschmidt 1940: Born in Eugene. The Oregonian, November 21, 2003.

- ^ Young, Bob (March 9, 2005). "Highway To Hell". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on April 30, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ Buel, Ron. "The Goldschmidt era". Willamette Week 25th Anniversary Edition. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ Wicker, Tom (May 25, 1972). "Mr. Mayor at 31". The New York Times.

- ^ Jaquiss, Nigel (March 9, 2005). "Goldschmidt's Web of Power". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Thompson, Gregory L. (2005). "How Portland's Power Brokers Accommodated the Anti-Highway Movement of the Early 1970s: The Decision to Build Light Rail" (PDF). Business and Economic History On-Line. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Moritz, Charles (1980). "Goldschmidt, Neil (Edward)". Current Biography. New York: H.W. Wilson Company.

- ^ "A Chronology of Dates Significant in the Background, History and Development of the Department of Transportation". U.S. Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 15, 2008. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ "Carter's Auto Rescue Sortie". Time. July 21, 1980. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ Broder, David S. (January 25, 1981). "Democrats, Going Home". The Washington Post.

- ^ Goldschmidt, Neil (January 21, 1981). "The Last Hurrah". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Transportation secretary blasted for 'blackmail'". Lodi News-Sentinel. December 7, 1979. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ FAA Historical Chronology, 1926–1996. Archived June 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved on February 10, 2008.

- ^ Peterson, Cass (March 3, 1981). "Staying in the transportation field". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ Gailey, Phil (December 12, 1984). "Democrats' Party Chief Search Focusing on Ex-Carter Aide". The New York Times.

- ^ Governor History Archived September 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine from ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Mapes, Jeff (December 23, 1990). "An uncertain legacy". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ^ "Prisons' director is slain in Oregon". The New York Times. January 19, 1989. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- ^ a b Jaquiss, Nigel (October 10, 2007). "Should you believe this man?". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ Zimmerman, Rachel (August 11, 1999). "Workers' Comp in Oregon May Be in for a Shake-Up". The Wall Street Journal. ProQuest 398658579.

- ^ Eure, Rob (November 1, 2000). "Workers' Comp Overhaul Has Both Sides Crying Foul". The Wall Street Journal. ProQuest 398730939.

- ^ "Straightening out workers' comp". The Oregonian. June 16, 2001. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "The 30-Year Secret". Willamette Week. May 12, 2004. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Hill, Gail Kinsey; Harry Esteve (May 9, 2004). "Secret's impact on a public life". The Oregonian.

- ^ Sulzberger, Arthur Gregg; Les Zaitz (October 24, 2007). "Giusto's job tangled with his private life". The Oregonian.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Don (July 20, 2001). "Hired grin". Portland Tribune. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- ^ Jaquiss, Nigel (March 9, 2005). "Goldschmidt's Web of Power (chart)" (PDF). Willamette Week. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ Young, Bob (August 26, 1998). "Big Dog". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on May 12, 2007.

- ^ "Citizen Neil". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on April 14, 2000.

- ^ a b c Mapes, Jeff; Gordon Oliver; Scott Learn (November 21, 2003). "The power broker". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2007.

- ^ Oregonian/OregonLive, The (June 27, 2004). "Gov. Ted Kulongoski's relationship with Neil Goldschmidt cut both ways". oregonlive. Archived from the original on January 10, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Varchaver, Nicholas (April 4, 2005). "One False Move". Fortune Magazine. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Redden, Jim (December 26, 2003). "Ex-guv's new job anything but certain". Portland Tribune. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ^ Redden, Jim (December 23, 2003). "Goldschmidt feels SAIF heat". Portland Tribune. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ^ "Goldschmidt still defending SAIF". Statesman Journal. Salem, Ore. January 2, 2004.

- ^ Redden, Jim (February 27, 2004). "Governor files pose a quandary". Portland Tribune. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ^ "Goldschmidt documents to be sent to Oregon state archives | The Seattle Times". archive.seattletimes.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Boulé, Margie (January 31, 2011). "Neil Goldschmidt's sex-abuse victim tells of the relationship that damaged her life". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ Esteve, Harry; Kinsey Hill, Gail (May 7, 2004). "Facing exposure, Neil Goldschmidt admits sexual relationship with 14-year-old girl while he was mayor of Portland". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ "Or. Rev. Stat. § 161.605 (2007)". Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Lucas, Dan. "The toxic legacy of Neil Goldschmidt lives on". Statesman Journal. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Goldschmidt, Neil (May 7, 2004). "Statement from Neil Goldschmidt". Archived from the original on July 11, 2004. Retrieved July 3, 2007.

- ^ "Shameless Self-Promotion". Willamette Week. May 25, 2005. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ a b Harden, Blaine (May 18, 2004). "The downfall of a political legend". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Christensen, Kim; Walth, Brent (June 17, 2004). "Confidant in scandal got help with SAIF". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ^ Hogan, Dave (May 15, 2004). "Goldschmidt surrenders law license". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Redden, Jim (June 4, 2004). "Goldschmidt digs in heels over his files". Portland Tribune. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ a b "State Archives Makes Goldschmidt Records Available". June 16, 2004. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ "Governor Neil Goldschmidt's Administration". Oregon State Archives. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ Hogan, Dave (February 23, 2005). "Political notebook: Goldschmidt records now available on the Internet". The Oregonian.

- ^ a b Jaquiss, Nigel (December 15, 2004). "Who knew". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ "Embattled Sheriff Giusto says he will retire at the end of this year". KATU News. February 7, 2008. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ "Neil Goldschmidt's Portrait Will Be Removed From Capitol". Willamette Week. March 7, 2011. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ Oregonian/OregonLive, The (May 9, 2004). "Former Gov. Neil Goldschmidt's sexual abuse of an underage girl sets his periodic retreats from a high-profile path in a different light". oregonlive. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "Neil Goldschmidt, former governor forever tainted by sexual abuse of young girl, dies". The Oregonian. June 12, 2024. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

External links[edit]

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- President Carter greets Secretary Goldschmidt, a photo published November 4, 1980, in The Oregonian, from that newspaper's flickr account.

- "Neil's network". Portland Tribune. May 21, 2004.

- 1940 births

- 2024 deaths

- 20th-century Oregon politicians

- American expatriates in France

- Businesspeople from Portland, Oregon

- Businesspeople from Eugene, Oregon

- Carter administration cabinet members

- Democratic Party governors of Oregon

- Disbarred American lawyers

- History of transportation in Oregon

- Jewish American members of the Cabinet of the United States

- Jewish American people in Oregon politics

- Jewish American state governors of the United States

- Jewish mayors of populated places in the United States

- Jews from Oregon

- Lawyers from Eugene, Oregon

- Mayors of Portland, Oregon

- Oregon lawyers

- Politicians from Eugene, Oregon

- Portland City Council members (Oregon)

- South Eugene High School alumni

- UC Berkeley School of Law alumni

- United States secretaries of transportation

- University of Oregon alumni

- Deaths from congestive heart failure