Norman Selfe

Norman Selfe | |

|---|---|

Studio portrait of Selfe | |

| Born | 9 December 1839 Teddington, England |

| Died | 15 October 1911 (aged 71) Sydney, Australia |

| Occupation | Civil engineer |

| Board member of | President, Board of Technical Education (1887–1889) |

| Spouses | Emily Ann Booth

(m. 1872–1902)Marion Bolton (m. 1906–1911) |

| Relatives | Maybanke Anderson (sister) Harry Wolstenholme (nephew) |

Norman Selfe (9 December 1839 – 15 October 1911) was an Australian engineer, naval architect, inventor, urban planner and outspoken advocate of technical education. After emigrating to Sydney with his family from England as a boy he became an apprentice engineer, following his father's trade. Selfe designed many bridges, docks, boats, and much precision machinery for the city. He also introduced new refrigeration, hydraulic, electrical and transport systems. For these achievements he received international acclaim during his lifetime. Decades before the Sydney Harbour Bridge was built, the city came close to building a Selfe-designed steel cantilever bridge across the harbour after he won the second public competition for a bridge design.

Selfe was honoured during his life by the name of the Sydney suburb of Normanhurst, where his grand house Gilligaloola is a local landmark. He was energetically involved in organisations such as the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts and the Australian Historical Society. As president of the Board of Technical Education, he fought consistently for the establishment of an independent system of technical education to serve the needs of a rapidly industrialising society. He was acknowledged upon his death as one of the best-known people in, and greatest individual influences upon, the city of Sydney.[1]

Family background and apprenticeship[edit]

Selfe came from a long line of inventors and engineers. Both sides of his family came from Kingston upon Thames in London, where one grandfather had owned a plumbing and engineering works.[2] His father Henry was a plumber and inventor, whose high-pressure fire-fighting hose was displayed at The Great Exhibition in London's Crystal Palace in 1851.[3] Selfe's cousin Edward Muggeridge grew up in the same town but moved to the United States in 1855, restyled himself Eadweard Muybridge, and achieved global fame as a pioneer in the new field of photography.[4]

It so happened that at the time of my visit to that cottage at the Quay that [Maybanke's] two clever brothers, Norman and Harry, had just completed the first "bike" ever made in Australia, known as a velocipede in those days, and these two young engineers were proudly just going "down the street" on their foot-worked machine, with the knowledge they were the first here to travel in such a contraption ...

Letter to the editor, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 April 1927[5]

The Selfe family landed at Sydney's Semi-circular Quay in January 1855, when Norman was 15 years old.[1] One of the reasons they emigrated to the colony of New South Wales was to enable him and his brother Harry to undertake engineering apprenticeships without having to pay the heavy premium required by large firms in London.[6] They initially resided in the nearby Rocks district in a small house that had previously been the first Sydney home of Mary Reibey, a former convict who became Australia's first businesswoman.[7] Selfe's parents had high expectations of their children, particularly of Norman, whose ability in mathematics and draughtsmanship was apparent from a young age. The brothers earned a reputation for innovation during their youth, and were the first to construct a velocipede in the country.[5]

Selfe very quickly began his career as an engineer, taking articles of apprenticeship to the ironmaster Peter Nicol Russell, at whose firm he worked in several departments and eventually became its chief draughtsman.[1] He would remain there until 1864.[8] In 1859, when PN Russell & Co expanded to a site in Barker Street near the head of Darling Harbour, Selfe drew up plans for the new works and the wharf, and oversaw their construction. In an address to the Engineering Section of the Royal Society of New South Wales in 1900, Selfe recalled his work for Russell's:

While there [I] prepared plans for numbers of flour mills, and for the first ice-making machines, designing machinery for the multifarious requirements of colonial industries, many of which (such as sheep-washing and boiling down) no longer exist on the old lines.[9]

While at Russell's, Selfe made several innovations in the design and construction of dredges for "deeping our harbours and rivers" – something of crucial importance to industry in early Sydney. He later recalled the success of Pluto, one of his dredges purchased by the government:

[I]n this there were several novelties introduced, and among them, the ladder was lifted by hydraulic power instead of by a chain from a winch ... The day of the official trial ... was a proud one for [me], because during the course of the little festivities which followed their formal approval and official acceptance, [head engineer] Mr Dunlop pointedly remarked that "as she was all right, the credit must be given to his boy in the drawing office".[10]

Inventor and engineer[edit]

Selfe achieved international recognition in 1861 when leading British journal The Engineer published illustrations of his designs for one of the first refrigerating machines. One such machine was installed behind the Royal Hotel in George Street in Sydney's ice-works – one of the world's earliest commercial refrigeration plants.[11] The decades following Selfe's arrival in Australia were watershed years in the development of refrigeration technology, and he was closely involved with its evolution. The introduction of refrigeration to the colony revolutionised farming, allowing the expansion of settlement, and made possible the export of meat and dairy products. In Sydney itself, refrigeration changed commercial practices and led to the eventual demise of city dairies. Selfe became an international authority on refrigeration engineering; he wrote articles and eventually a definitive textbook on the subject, published in the US in 1900.[12]

After leaving Russell's, Selfe went into partnership with his former employer James Dunlop. They designed and built major installations for the Australasian Mineral Oil Company, the Western Kerosene Oil Company and the Australian Gas Light Company.[13] In 1869 Selfe was appointed to the senior post of "chief draftsman and scientific engineer" at Mort's Dock and Engineering Company in Balmain.[1][14] In this role he oversaw the design and construction of the mail ship SS Governor Blackall, personally commissioned for the Queensland government by the Premier Charles Lilley in 1869.[15] The Sydney-built but Queensland-owned ship was an attempt to break what was later described as the "capricious monopoly" of the Australasian Steam Navigation Company on coastal trade and mail delivery from England. However, it ultimately caused the political downfall of Lilley as he had undertaken the contract without consulting his colleagues.[16]

Selfe left Mort's in 1877 to practise as a consulting engineer at 141 Pitt Street, gaining a reputation for versatility and originality. Upon his return from an overseas trip through America, Britain and continental Europe in 1884–85, where he visited engineering works and technical education facilities in search of new ideas to take back to Sydney, Selfe set up a new office in Lloyd's Chambers at 348 George Street.[11] He would later move to No. 279 where he operated the consultancy until his death in 1911. In the late 1890s he employed William Dixson as an engineer, who would later make a major donation of Australiana to the State Library of New South Wales.[17] The collection of Selfe's own papers and drawings have since been donated to the same library that his former employee greatly augmented.[18]

Selfe designed the hulls or the machinery for some 50 steam vessels, including two torpedo boats for the New South Wales government, which he claimed were the fastest boats on the harbour for 20 years,[19] and the SS Wallaby, Sydney Harbour's first double-ended screw ferry.[1][20] Double-ended hulls remain the design of Sydney's current Freshwater-class ferries. He designed the first concrete quay wall in Sydney Harbour, and wharves for deep-sea vessels. He also designed the first ice-making machines in New South Wales, introduced the first lifts, patented an improved system of baling wool which increased capacity fourfold, and oversaw hydraulic and electric light installations in the city and the carriages on its railway network.[1][13] He planned mills, waterworks and pumping stations, including the high-level pumps at the reservoir on Crown Street. He made major electric light installations at the Anthony Hordern & Sons department store and the Hotel Australia, and provided a hot-water system for the hotel.[20] He designed machinery for factories, dairies and railways, including, in 1878, the incline of what is now the Scenic Railway attraction at Katoomba in the Blue Mountains – which claims to be the world's steepest.[21] Its original purpose was the transportation of coal[22] from the Jamison Valley to the cliff-top.[23]

During his lifetime Selfe received both local and international recognition for his engineering skill. He had been president of both the Australian mechanical engineers' and naval architects' institutes as well as a member of both the British equivalent organisations. He was also elected a full member of the English Institution of Civil Engineers and, by virtue of his writings also being published in Chicago, also an honorary member of an American engineering association.[1]

Sydney[edit]

Selfe's capacity for invention was not limited to the realm of machinery – he was also an energetic civic and urban reformer. He had high hopes for Sydney:

"Every well wisher of Sydney, who sees and understands what magnificent latent possibilities there are before her must hope that she will for all time be the Queen City of the Southern Hemisphere; and that the new century will open finding old ways departed from, and a glorious new era of progress, prosperity, morality and cleanliness installed in our midst. When that day arrives, we shall look back with curiosity and wonder at the continued blindness and negligence from which our city – so highly gifted by nature – had suffered so long."[24]

From the time of Selfe's return in 1886 from two years' travel in the United States and Europe, he campaigned for improvements to the city of Sydney. These included proposals for a city railway loop, the redevelopment of the Rocks, and a bridge to the North Shore.[25] His obituary in The Sydney Morning Herald noted, "Mr. Selfe for over twenty years was a strenuous advocate of a circular city railway that should connect up the eastern, western, and northern suburbs of the city with the marine suburbs of the harbour, and stations adjacent to the ferries".[1] He published plans and proposals elaborating on his ideas, and produced major articles with titles like "Sydney: past, present and possible"[26] and "Sydney and its institutions, as they are, and might be from an engineer's point of view".[27]

In 1887 Selfe published proposals for a city underground railway, with stations at Wynyard, the Rocks and Circular Quay, and a loop to Woolloomooloo and the eastern suburbs. The proposal included a bridge across Sydney Harbour for trains, vehicles and pedestrians. He presented these schemes to the Royal Commission on City and Suburban Railways in 1890; but nothing was to come of it, largely because the 1890s depression brought public works initiatives to a standstill.[25]

In 1908–09 he served as one of 11 expert commissioners to the Royal Commission for the Improvement of the City of Sydney and its Suburbs. Selfe's proposals included an overhead railway station at Circular Quay and major landscaping works at Belmore Park opposite Central Railway Station.[28] Both of these visions were later realised, but not in his lifetime.[29]

Sydney Harbour Bridge[edit]

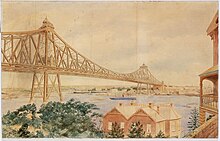

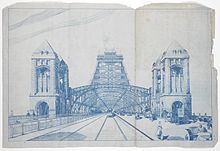

By the late 1890s a harbour crossing and a city railway extension were again on the agenda. The Lyne government committed to building the new Central Railway Station, and organised a worldwide competition for the design and construction of a Harbour Bridge. Selfe submitted a design for a suspension bridge estimated to cost £1,128,000 and won the second prize of £500. The first prize went to G. E. W. Cruttwell, of Westminster with a design estimated to cost more than twice as much.[30] After the outcome of the competition had become mired in controversy, in 1902 Selfe won a second competition outright, with a design for a steel cantilever bridge stretching from Dawes Point to McMahons Point. The selection board were unanimous, commenting that "The structural lines are correct and in true proportion, and ... the outline is graceful".[31]

Construction of Selfe's version of the Sydney harbour bridge never started due to an economic slowdown and a change of government at the 1904 state election. Much to Selfe's outrage, the Department of Public Works kept his calculations and drawings, and also copied and printed them. Eventually in 1907, the department contacted Selfe and asked him to collect his drawings, but refused to return the calculations. Selfe was never given the £1,100 prize, nor was he paid for his subsequent work which he estimated to be worth more than £20,000.[32]

Among the Selfe family papers in Mitchell Library there is a large collection of postcards featuring bridges from across the world.[33] Some were sent to Selfe by friends and relatives from Japan, Italy, New Zealand, and Switzerland. Others, un-postmarked, were collected on his travels in 1884–85. These would have formed a research catalogue of contemporary international bridge-building practices for Selfe's own designs.

In 1908, Selfe presented new proposals based upon the old design to the Royal Commission on Communication between Sydney and North Sydney. However, this time the commissioners preferred a tunnel scheme; again, no work proceeded. Agitation for a bridge was renewed with the election of a Labor government at the 1910 state election. But with Selfe's death in 1911, it was time for a new generation of bridge builders. In 1912 the government appointed J.J. Bradfield as "engineer-in-chief of Sydney Harbour Bridge and City Transit"; the call for tenders for constructing the bridge was not made until a decade later.[34] Over the following decades, versions of what Selfe had much earlier articulated for a city circle railway link and a bridge to the north shore were realised. Selfe's contribution received little public or formal recognition.[35][36]

Historian[edit]

Selfe was founding vice-president of the Australian Historical Society in 1901, serving with president Andrew Houison and patron David Scott Mitchell (after whom the Mitchell wing of the State Library of New South Wales is named).[37] He remained actively involved in the society for 10 years, despite what he called "the evident lack of interest ... taken in the proceedings of the Society" by the general public in the early years.[38] The society got off to a shaky start, with low attendance of lectures and meetings.[39] Early papers delivered by Selfe included "A century of Sydney Cove"[40] and "Some notes on the Sydney windmills".[41] Slowly, interest increased, and by 1905 membership had reached 100.[42] Known as the Royal Australian Historical Society (RAHS) since 1918, and housed in a grand Victorian style townhouse on Macquarie Street, the organisation is Australia's oldest historical society; Selfe is celebrated as one of its pioneers.[39]

Technical education[edit]

Selfe was a key figure in the history of technical education in New South Wales. He advocated a more utilitarian and less literary education system, to produce a skilled workforce that could realise Australia's potential as an efficient industrial state. He was utopian in his vision:

There is no doubt that it is on the work of tools directed by brains that the future of Australia depends more than anything else. With tools our Australian deserts may be turned into gardens ... They will pluck the hidden treasure from the bowels of the earth, enable us to soar in the air, or explore the depths of the water. They will weave a network of communication over our island continent, dot it with the homes of a happy people, and minister to our wants in providing not only the necessities and comforts of life, but the most refined luxuries that are needed to satisfy the novel and exacting wants which arise every day, as the standard of intellectual and technical cultivation is raised and extended among us ...[43]

Selfe believed an overhaul of education was needed, from kindergarten to tertiary study. His concept of technical education encompassed Friedrich Fröbel's kindergarten activities based around play and occupations; the teaching of drawing, manual work and science in schools; and specialised practical training of workmen and professionals in technical colleges.[44] He argued for the establishment of a new kind of university – an "industrial university", less theory-oriented and more concerned with the practical and the useful.[45] He saw technical education as a distinct sphere of education to be administered and delivered by people with practical industry experience, not government officials or traditional teachers.[11]

Teacher[edit]

As early as 1865 Selfe gave regular classes in mechanical drawing to tradesmen at the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts in Pitt Street.[46] Selfe's class in mechanical drawing was the first technical, vocational offering at the School of Arts, and its popularity led to the introduction of other practical subjects.[47]

Due to the colony's rapidly expanding population and demand for skilled labour, there were increasing calls in the 1870s for a formal system of technical education. In 1870, Selfe helped found the Engineering Association of New South Wales which amalgamated into Engineers Australia in 1919.[48] He was its president from 1877 to 1879 and Engineers Australia annually awards the "Norman Selfe Medal" to a student at the Australian Maritime College.[49] In 1878, the association joined forces with the New South Wales Trades and Labour Council and the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts to form the Technical and Working Men's College. The college initially operated as an agency of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts.[50] The college occupied premises in Pitt, Sussex and Castlereagh Streets, and rooms in the Royal Arcade, before it moved to Ultimo in 1889.[47] The college later became the Sydney Technical College out of which grew the University of New South Wales, the University of Technology, Sydney, and the National Art School. The Ultimo buildings still serve their original purpose, now as the main campus of the Sydney Institute of TAFE.[51]

In 1880, Selfe became vice president of the School of Arts. He supported the school's Working Men's College, but felt a more thorough focus on practical skills was needed. He rejected the non-technical, non-practical approach of the school's model and campaigned instead for the establishment of a proper institute of technical education, where instructors would be skilled tradesmen with practical industrial experience. He also pushed for the expansion of technical education facilities into the suburban and regional districts.[52]

Critic[edit]

On 1 August 1883 the New South Wales government made a proclamation which transferred control of the Technical and Working Men's College to an independent Board of Technical Education, to which Selfe was appointed, and assumed financial responsibility directly.[53] The government also provided funds to fit out workshops in Kent Street that opened in 1886.[54] This was an initiative driven by Selfe, who had admired the workshop teaching model abroad. It represented a major innovation in technical education in New South Wales.[55]

Many of the board's initiatives were based on observations made abroad by Selfe and board president Edward Combes, or recommendations made by the British Royal Commission into Technical Education of 1881–84. However, most of the board's schemes were frustrated by an unresponsive colonial government.[56] Norm Neill, historian of the early years of the Sydney Technical College, argues that the Board caused many of its own problems:

There was a marked lack of unity ... Members either resigned or became inactive [and the Board failed] to accept that its autonomy was more nominal than real. Any expansion of technical education was dependent on government funding and governments were unlikely to allocate resources to an organisation unwilling or unable to cooperate.[57]

Selfe was president of the Board from January 1887 until it was disbanded in 1889. During this time the relationship between the board and the government deteriorated with Selfe being overtly critical of two powerful institutions: the newly formed Department of Public Instruction and the University of Sydney.[58] Selfe strongly opposed the government's taking control of technical education, which had been underway since the government first declared its interest in doing so at a special meeting of the Sydney Mechanics School of Arts in September 1883.[59][60] He also did not support an alternative proposal that the University of Sydney should take over.[61] In an address at the annual presentation of prizes at Sydney Technical College in 1887, Selfe alienated the Minister of Public Instruction and others by being openly contemptuous of the traditional pursuits of schools and universities:

[T]he whole experience of the past goes to show that the learning of the schools has had little, if anything, to do with the material advancement of the world, and that while it may have produced intellectual giants, subjective teaching has not brought forth those men who have been inventors and manufacturers that have entirely changed the character of our civilisation.[45]

Selfe criticised the classical liberal arts education offered at the University of Sydney as elitist. In his 1888 address to Sydney Technical College students on prize night, he again caused affront to the establishment when he called for greater diversity of educational opportunities in the colony:

[I]t is not ... easy ... to see why the general public should pay so many thousands a year to make our future professional men in medicine and law in the colony, to form part of the so-called upper classes, when our "principles" will not allow us to pay just a little more in order to have, say, our locomotives made here, and when we are doing so very little, proportionately, to train and educate the artisans who make these locomotives, and who belong to a much less wealthy and influential level in society.[62]

In 1889 the colonial government, already in financial control, assumed direct operational control by abolishing the Board and placing the college within the Technical Education Branch of the Department of Public Instruction (now the New South Wales Department of Education).[63]

Reformer[edit]

In the early years of the 20th century, education remained a major political issue in New South Wales. While Selfe would not be drawn again into the centre of the fray, he supported the efforts of his sister Maybanke and her second husband Francis Anderson towards education reform.[58] Following the Knibbs-Turner Royal Commission into New South Wales Education in 1902, and the appointment of Peter Board as Director of Education in 1905, many of Selfe's ideas for technical education were implemented.[64] Ultimately, in 1949, a separate Department of Technical Education was created, and the New South Wales University of Technology (later the University of New South Wales) was established at Kensington.[65]

Les Mandelson, historian of Australia's education systems, categorises Selfe as "a nineteenth century protagonist for the New Education", who helped pave the way for the extensive reforms of the twentieth century. "Without him", he adds, "education in the late nineteenth century would have been decidedly more mundane". However, Mandelson sounds a critical note:

Selfe's contempt for the liberal arts tradition and the priority he accorded practical skill have certain implications which cannot be commended. These reflected and augmented ... one of the less attractive features of the Australian ethos – indifference to higher learning and advanced attainments, an indifference shading into contempt and suspicion ... Selfe may have lost a battle but before long, the liberal arts tradition faced still greater defeats. To these, Selfe certainly contributed, and what must be recognised is that in the vehemence of the struggle, and in the lauding of efficiency over culture, much that was valuable in the liberal arts tradition was lost.[66]

Biographer Stephen Murray-Smith is more generous in his assessment of Selfe's contribution to education debates around the turn of the twentieth century: "Selfe went beyond the concept of helping the working man to achieve a share of the good things hitherto reserved for others, towards the concept of leading him to create good things for himself."[67]

Selfe was a noted activist for the Federation of Australia being a member of the Central Federation League.[11] Edward Dowling, his colleague on the inaugural board of the Australian Historical Society, was also the Secretary of the Central League of the Australasian Federation League[68] and his former articled engineer John Jacob Cohen would later be elected at the 1898 New South Wales election in the seat of Petersham representing the National Federal Party.[69]

Personal life[edit]

When Selfe obtained a steady job after his apprenticeship, he brought his family with him from The Rocks to live at Balmain. Selfe bought waterfront land and built twin terraced houses called Normanton and Maybank, which are still at 21 and 23 Wharf Road, Birchgrove. It is likely that Selfe shared Normanton with his widowed mother. Next door lived his brother Harry, his sister Maybanke and his brother-in-law Edmund Wolstenholme.[7]

Selfe was a supportive brother, both emotionally and materially. His sister Maybanke bore seven children to her first husband Edmund, four of whom died as infants from tuberculosis.[7] He also provided financial support after Maybanke's marriage came to an end. Maybanke earned fame in her own right as a prominent suffragist and pioneer of education for women and girls. In the 1890s brother and sister campaigned together for education reform.[70]

On 10 October 1872 at St Mary's Church, Balmain Selfe married Emily Ann Booth, the daughter of John Booth, a well-known shipbuilder and Balmain's first mayor (and formerly the member for East Macquarie in the colonial parliament).[71] They lived for many years at Rockleigh in Donnelly Street, Balmain, a house that has since been demolished. In 1884 their first daughter Rhoda Jane was born, followed by a stillborn daughter in 1886,[72] and then Norma Catherine in 1888.[73] In 1885 Selfe bought land in Ashfield and designed a grand house called Amesbury. Described at the time as having "more novelties both externally and internally than any other house in the colony"[74] including terracotta lyrebird reliefs by artist Lucien Henry on the front wall, and a tower purpose-built for Selfe to pursue his hobby of astronomy.[75] Built around 1888 to honour the centenary of the colony, Amesbury still stands at 78 Alt Street and was used by Brahma Kumaris from 1986 as its Australian headquarters[76] until 2014 when it was auctioned for over $3.5 million.[77] As children, Rhoda and Norma attended their Aunt Maybanke's school in Dulwich Hill.[70] As adults, they trained in Italy with educator Maria Montessori and returned to Sydney to open a Montessori school of their own in the building known as Warwick on Bland Street, Ashfield.[78]

Around 1894, the family moved, this time to Hornsby Shire, where a new Selfe-designed house, Gilligaloola, was built on 11 acres (4.5 ha) purchased by Selfe ten years earlier. Situated at what is now 82 Pennant Hills Road, the house is still a local landmark, notable for its distinctive tower and twin chimneys.[79] Selfe was a committed citizen and a natural spokesman for the local community, to the extent that when the railways needed a name for the locality, the community chose Normanhurst (though Selfe himself felt that St Normans would have been "much more elegant and suggestive").[80]

On 12 May 1906, four years after the death of his first wife, Selfe married Marion Bolton at St Philip's Church, Sydney.[81]

Death[edit]

Selfe died suddenly on 15 October 1911. His death certificate states the cause of death as "heart failure brought on by exertion".[11] His daughter Norma offered some context to a journalist in 1957. She said:

"On the day of his death he climbed trees in the church grounds to lop branches, as the gardener was too nervous to climb so high. That night he died in his sleep."[82]

Norma reported that her father had been sanguine to the end, playful with his nephews and learning to play the oboe. However, other reports suggest that Selfe was concealing a bitter sense of disappointment at the end of his life, most particularly over the Harbour Bridge affair. His obituary in the journal Building concluded:

... [T]here is none today who can replace the noble personality, that keen energetic brain ever ready to give of its wonderful store of knowledge, and that happy spirit ever bright, ever optimistic, even though crushed beneath the cruel and unjust blow of the non-acceptance of his prize design for the North Shore bridge. "It will crown my life" he said. We will always remember the bright gleam in his eyes as they peered beyond the anxiety of today, looked afar to the future glory of his beloved Sydney where in his dreams he saw his mighty bridge spanning what he called "God's noblest waterway".[83]

Selfe's funeral was held at St Paul's Church, Wahroonga, where he had been a churchwarden. He was buried in Gore Hill cemetery in the presence of a large gathering of businessmen and representatives of the organisations he had been involved with.[84] He was survived by his two daughters from his first marriage, Rhoda and Norma, and his second wife, Marion. His estate was valued for probate at nearly £5000.[13] Twenty-one years later, on 11 March 1932 Marion's charred body was found in her new house, also in Normanhurst where she lived alone, having reportedly set fire to her clothes when lighting a candle.[85] Marion was buried alongside Norman in plot CE I:7. Rhoda's ashes were also placed nearby when she died aged 69 in 1954, still living in Gilligaloola.[86][87]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h "A Bridge Builder: Death of Norman Selfe, a distinguished career". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 October 1911. p. 8. Retrieved 6 April 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Mandelson, L.A. (1972). "IV: Norman Selfe and the Beginnings of Technical Education". In C. Turney (ed.). Pioneers of Australian Education. Vol. 2. Sydney: Sydney University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-424-06440-6.

- ^ Roberts, Jan (1993). Maybanke Anderson: Sex, suffrage and social reform. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-86806-495-6.

- ^ Anderson, Maybanke (2001). "My Sprig of Rosemary". In Roberts, Jan; Kingston, Beverley (eds.). Maybanke, A Woman's Voice: The collected work of Maybanke Selfe – Wolstenholme – Anderson, 1845–1927. Avalon Beach, New South Wales: Ruskin Rowe Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-9587095-3-8.

- ^ a b "Maybanke Anderson". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 April 1927. p. 8. Retrieved 31 January 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Anderson 2001, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Jan (2010). "Anderson, Maybanke". Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 22.

- ^ Selfe, Norman (1900). "Annual Address Delivered to the Engineering Section of the Royal Society of NS Wales, June 20, 1900". Journal of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 34: xxviii. ISSN 0035-9173. Cited in Freyne (2009).

- ^ Selfe 1900, p. xxx.

- ^ a b c d e Freyne, Catherine (2009). "Selfe, Norman". Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Arthur, Ian (2001). Norman Selfe, Man of the North Shore. unpublished essay submitted for the North Shore History Prize. pp. 3–6. Cited in Freyne (2009)

- ^ a b c Murray-Smith, Stephen (1976). "Norman Selfe (1839–1911)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 6. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 33.

- ^ Pugh, Ann. "One hundred years ago – the Foundation of the Engineering Association of New South Wales". The Journal of the Institution of Engineers. 1970 (July–August): 86. ISSN 0020-3319.

- ^ "Famous ship". The Brisbane Courier. 5 August 1931. p. 16. Retrieved 4 February 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Cook, B (1981). "Sir William Dixson (1870–1952)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 8. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ "Selfe family papers and pictorial material collection" (Series 1-10: Architectural and Technical Drawings; Graphic Materials; Textual Records). State Library of New South Wales. 1853–1948. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Arthur 2001, p. 7.

- ^ a b Norman Selfe, Memorandum of a few of the engineering works carried out in New South Wales by Norman Selfe, State Library of NSW, Mitchell Library manuscripts SS 3864 Box No 6

- ^ "Scenic Railway". Scenic World. 2013. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Burning Mists of Time ISBN 978 09775639 6 8 Pells/Hammon PAGE 66

- ^ Low, John (1994). "From Coal Mine to Scenic Railway". Blue Mountains: Pictural Memories. Alexandria, New South Wales: Kingsclear Books. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-908272-37-2.

- ^ Selfe 1900, p. xiviii.

- ^ a b Arthur 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Selfe, Norman (1908). Sydney, past, present and possible: an address to the Australian Historical Society on November 27th, 1906. Sydney: D. S. Ford. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ Selfe, Norman (April 1900). Sydney and its institutions: as they are and might be from an engineer's point of view. Vol. XV. Sydney: Engineering Association of New South Wales. p. 19. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Report of the Royal Commission for the Improvement of Sydney and its Suburbs, New South Wales Parliamentary Papers, vol 5, 1909. Cited in Freyne (2009).

- ^ Arthur 2001, pp. 25–27.

- ^ "Cablegrams". Zeehan and Dundas Herald. 30 November 1900. p. 3. Retrieved 6 February 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Arthur 2001, pp. 21–24.

- ^ "The North Shore Bridge Competitions: Précis of Correspondence with the Government in the same, moved for in Parliament by Dr Arthur, printed under No 9 Report of Printing Committee, 18 Dec 1907", Papers of Adeline Hicking, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library manuscripts 6537 Archived 19 February 2013 at archive.today. Cited in Freyne (2009)

- ^ Norma Selfe and Rhoda Selfe papers c1900–48, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library manuscripts 3864, box 10 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Design tenders and proposals". Sydney Harbour Bridge. NSW Board of Studies. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ "Late Mr. Norman Selfe". The Sydney Morning Herald. 27 May 1925. p. 18. Retrieved 2 December 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Arthur 2001, pp. 27–28.

- ^ "Founders – Office-Bearers, 1901". Royal Australian Historical Society. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Minutes of meeting, 1 June 1903 RAHS, cited by Jacobs, Marjorie (2001). "Students of a Like Hobby: the Society 1900–1954". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 87 (1): 19.

- ^ a b "History of the RAHS". Royal Australian Historical Society. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Selfe, Norman (1902). "A Century of Sydney Cove". Journal and Proceedings of the Australian Historical Society. 1 (4).

- ^ Selfe, Norman (1902). "Some Notes on the Sydney Windmills". Journal and Proceedings of the Australian Historical Society. 1 (6).

- ^ Jacobs, Marjorie (2001). "Students of a Like Hobby: the Society 1900–1954". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 87 (1): 19.

- ^ Selfe, Norman (1889). Three Addresses on Technical Education by Norman Selfe, MICE, MIME, etc, Vice-President and Acting President of the Board of Technical Education of New South Wales, delivered at the Annual Meetings of the Sydney Technical College in 1887, 1888 and 1889. Sydney: Board of Technical Education. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2013. p. 10. Cited in L.A. Mandelson (1972) pp. 128–131

- ^ Mandelson 1972, p. 138.

- ^ a b Selfe 1889, p. 11.

- ^ Selfe 1889, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Neill, Norm (1991). Technically & Further: Sydney Technical College 1891–1991. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-86806-426-0.

- ^ "Engineering Association of New South Wales (1870–1919)". Encyclopedia of Australian Science. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ "Category E – Awards to Tertiary Education Students". Awards. Engineers Australia. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Mandelson 1972, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Freyne, Catherine (2010). "Sydney Technical College". Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Mandelson 1972, pp. 113–114.

- ^ NSW Government Gazette, No. 324, 1 August 1883, p. 4173

- ^ Neill 1991, p. 10.

- ^ Mandelson 1972, p. 121.

- ^ Mandelson 1972, pp. 121–123.

- ^ Neill 1991, p. 12.

- ^ a b Mandelson 1972, p. 136.

- ^ Dunn, Mark (2011). "Technical and Working Men's College". Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Transfer of the Technical College to the Government". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 September 1883. p. 6. Retrieved 7 April 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Mandelson 1972, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Selfe 1889, p. 16.

- ^ "Our history: The government steps in". About TAFE NSW. TAFE NSW. 2010. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 155.

- ^ Mandelson 1972, p. 137.

- ^ Mandelson 1972, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Murray-Smith, Steven (1966). A History of Technical Education in Australia (PhD Thesis). University of Melbourne. Cited in Arthur (2001) p.17

- ^ Jacobs, Marjorie (1988). "The Royal Australian Historical Society 1901–2001: Part I 'Students of a like hobby': the Society 1900–1954". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 73 (4): 243–246. ISSN 0035-8762. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Holt, H.T.E (1981). "John Jacob Cohen (1859–1939)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 8. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ a b Roberts 1993, p. 54.

- ^ "Family notices". The Empire. Sydney. 16 October 1872. p. 1. Retrieved 1 February 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Family Notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. 6 October 1886. p. 1. Retrieved 7 April 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Family Notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. NSW. 8 May 1888. p. 1. Retrieved 28 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Ten-bedroom mansion with four-storey tower to fetch astronomic price". News.com.au. 15 August 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Godden Mackay Logan. "Ashfield Heritage Study – 'Amesbury'" (PDF). Heritage Inventory. Ashfield Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Locations near you". Brahma Kumaris. 2014. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "78 Alt Street Ashfield NSW 2131". realestatate.com.au. September 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "Advertising". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 January 1918. p. 6. Retrieved 4 February 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Arthur 2001, p. 35.

- ^ Selfe, Norman (July 1910) Some account of St Paul's Church, Hornsby (now Normanhurst and Wahroonga): with a few reminiscences of the old village of Hornsby, printed for the subscribers, p. 14. Cited in Freyne (2009)

- ^ "Family notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 May 1906. p. 8. Retrieved 1 February 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Brodsky, Isadore (4 November 1957). "A man ahead of his time". The Sun. p. 27.

- ^ Obituary, Building, 16 October 1911, Cited in Arthur (2001) p.38

- ^ "Late Mr. Norman Selfe". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 October 1911. p. 16. Retrieved 2 December 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Burnt to death". The Brisbane Courier. 12 March 1932. p. 5. Retrieved 31 January 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Family notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 January 1954. p. 24. Retrieved 5 February 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "SAN-SMA". Gore Hill Cemetery: Graves Index. Willoughby City Council. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

External links[edit]

- Biographical article and Database record at the Dictionary of Sydney.

- Article at the Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- Selfe family papers and pictorial material, 1853–1948 at the State Library of New South Wales.

written by Catherine Freyne, 2009 and licensed under CC BY-SA. Imported on 10 May 2012.