Operation Olive Leaves

| Operation Olive Leaves | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Retribution operations (during Palestinian Fedayeen insurgency) | |||||||

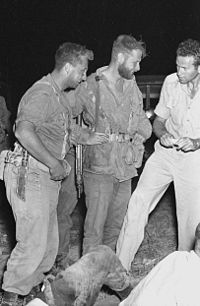

Ariel Sharon (left), overall commander of Operation Olive Leaves, consults with Aharon Davidi (center), commander of the 771 Reserve Paratroop Battalion and Company Commander Yitzchak Ben Menachem (right), who was killed during the assault. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Ariel Sharon Rafael Eitan Aharon Davidi Meir Har-Zion Yitzchack Ben Menachem † | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

6 killed 10 wounded |

54 killed 30 captured | ||||||

Operation Olive Leaves (Hebrew: מבצע עלי זית, Mivtza ʿAlei Zayit) also known as Operation Kinneret (the Hebrew name for the Sea of Galilee) was an Israeli reprisal operation undertaken on December 10–11, 1955, against fortified Syrian emplacements near the north-eastern shores of the Sea of Galilee. The raid was an unprompted attack. The successful operation resulted in the destruction of the Syrian emplacements. The Syrians also sustained fifty-four killed in action. Another thirty were taken prisoner. There were six IDF fatalities.[1]

Background

[edit]Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Syria and Israel negotiated an armistice arrangement, signed on July 20, 1949,[2] which provided for the establishment of demilitarized zones (DMZ) on the border between Israel and Syria. Disputes soon arose concerning sovereignty over the DMZs leading to periodic border clashes and constant border tensions.[3] Despite the fact that the armistice agreement had placed the demarcation line ten meters east of the sea, and the international border passed inland from the east bank of the Sea of Galilee, which placed the entire sea and surrounding shoreline under Israeli sovereignty, the Syrians placed their military positions directly on the shoreline, and Syrian gunners fired on Israeli patrol boats that came within 250 meters of the shore. Moreover, there were a number of border transgressions involving Syrian fishermen and farmers, who, under the protection of Syrian guns, continued to utilize the sea for fishing and irrigation.[3] However, Operation Kinneret did not follow any unusual events. On the day before the operation, an Israeli police boat was deliberately sent close to the Syrian shore, in order to provoke a response. It succeeded in drawing fire from a Syrian gun, scraping some paint off the bottom of the boat. This was the justification for the assault.[3][4][5] The operation had been planned and trained for, with evidence that indicated it had been rehearsed. There had been no Syrian provocation. [6] Israel's newly re-elected Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion ordered a large-scale operation to destroy Syrian gun emplacements along the shoreline in response to the "extended period of Syrian provocative actions and extended shootings". He did not consult the Cabinet, nor the Foreign Ministry. Moshe Sharett, who was in the United States attempting to acquire weapons, had told Gurion that any attacks could negatively affect these talks. In addition, the Israelis hoped to take Syrian prisoners who could be exchanged for four Israelis held captive by Syria.[7][8][9] Ariel Sharon was given overall command of the operation.[10]

Israel's newly re-elected Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion decided that a response was necessary, and ordered a large-scale operation to destroy Syrian gun emplacements along the shoreline in response to the "extended period of Syrian provocative actions and extended shootings". In addition, the Israelis hoped to take Syrian prisoners who could be exchanged for four Israelis held captive by Syria under brutal and inhumane conditions.[11][8][12] Ariel Sharon was given overall command of the operation.[13] Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett was in the United States to negotiate a possible arms purchase at the time.[14]

The battle

[edit]

On the night of 11–12 December 1955 the operation began. Following artillery and mortar barrages against Syrian positions, elements of the 890th Paratroop Battalion, augmented by units of Aharon Davidi's 771 Reserve Paratroop Battalion as well as units from the Nahal and Givati Brigades commenced their attack. The complex operation involved a two-column attack from the north and south, which included both infantry and armored vehicles, as well as an amphibious assault conducted by troops who crossed the sea by boats of Shayetet 11. Sharon directed the operation from a small plane circling the battle area.[4][15][5] The combined force raided Syrian emplacements along the Kinneret's northeastern shoreline north of Kibbutz Ein Gev until the Jordan River estuary, and destroyed all the gun emplacements they attacked. The Syrians suffered fifty-four killed in action and another thirty Syrian soldiers were taken prisoner. The Israelis lost six soldiers, with another ten wounded. Among these was Company Commander Yitzchak Ben Menachem, a highly regarded soldier and Israeli hero of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War[16] who was killed by a Syrian hand grenade while attacking Syrian positions near Akib.[17] His death notwithstanding, the mission was regarded as an unmitigated success. Political fallout generated by the operation would later prompt Ben-Gurion to comment, somewhat sarcastically, that it may have been "too successful".[14]

Aftermath

[edit]

Though militarily successful, political fallout from the operation was immediate. It drew a United Nations rebuke[18] and it resulted in the postponement of Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett's arms request (the US government had decided to approve it on the eve of the attack, but retracted when the news came out). It also killed the prospect of direct US military assistance for the time being.[19] Sharett himself was outraged upon hearing of the operation. From the United States, he sent a strongly-worded cable of protest to Ben-Gurion, and concluded it by questioning whether there was one government in Israel, whether it had its own policy, and whether its policy was to sabotage its own objectives. Sharett also expressed suspicion to Abba Eban that Ben-Gurion had deliberately ordered the raid to deny him a personal victory in the arms request. Each of the UN Security Council's members denounced the attack while praising Syria's moderation. In January 1956 the Security Council passed a resolution threatening Israel with sanctions in the event of further breeches of the armistice agreements. [19][14]

Upon his return home, Sharett berated Ben-Gurion's military secretary when the latter greeted him at the airport, accusing him of betrayal. In Israel, Sharett continued to sharply criticize Ben-Gurion for ordering the raid, once remarking that "Satan himself could not have chosen a worse timing." He bitterly complained that Ben-Gurion exceeded his authority when he failed to consult the Cabinet and Foreign Ministry. Commenting on the decision-making process, he remarked that "Ben-Gurion the defense minister consulted with Ben-Gurion the foreign minister and received the green light from Ben-Gurion the prime minister". Cabinet ministers were also stunned by the raid, and were critical of the scope and timing of the raid. Ministers demanded that in the future, all proposed military operations be brought before the cabinet for approval. One minister charged that the IDF was pursuing an independent policy and trying to impose its will on the government, while others speculated that it had exceeded the orders it had been given while expanding the operation's scope.[19][14]

Nonetheless, the operation was a tactical success and achieved two important objectives. First, it impressed upon the Syrians the might which Israel could bring to bear if provoked. Indeed, it has been suggested that Syria's failure to act militarily on behalf of its Egyptian ally during Israel's Operation Kadesh was a consequence of Operation Olive Leaves.[15] Second, Israel's capture of numerous Syrian soldiers during the raid helped facilitate the release of its four captives held by Syria. On March 29, 1956, a prisoner exchange was effectuated and the four were returned to Israel after enduring fifteen months of captivity in Syria.[20][8]

References

[edit]- ^ Spencer Tucker, The encyclopedia of the Arab-Israeli conflict, ABC-CLIO, (2008) p. 232

- ^ Walter Eytan, The First Ten Years, Simon & Schuster (1958), p. 44

- ^ a b c "Arab-Israeli wars: 60 years of conflict". ABC-CLIO History and the Headlines.

- ^ a b Almog, Orna: Britain, Israel and the United States, 1955-1958: Beyond Suez

- ^ a b Tyler, Patrick: Fortress Israel: The Inside Story of the Military Elite Who Run the Country--and Why They Can't Make Peace

- ^ Sharett’s diary, 13 Feb. 1955; Hutchison, Violent Truce , 109–10; Burns, Between Arab and Israeli , 107–8; Hameiri, “Demilitarization and Conflict Resolution,” 107; Tal, “Development of Israel’s Day-to-Day Security Conception,” 329; and Morris, Israel’s Border Wars , 364–69. 13 . Sharett to Ben-Gurion, 27 Nov. 1955,

- ^ Ze'evi Derori, Israel's reprisal policy, 1953–1956: the dynamics of military retaliation, Frank Cass (2005), p. 157

- ^ a b c Ephraim Kahana, Historical dictionary of Israeli intelligence, (Scarecrow 2006) pp. 118–119

- ^ Bar-Zohar, Michael (1998). Lionhearts: Heroes of Israel. Warner Books. p. 187.

- ^ Derori (2005), p. 159

- ^ Ze'evi Derori, Israel's reprisal policy, 1953–1956: the dynamics of military retaliation, Frank Cass (2005), p. 157

- ^ Bar-Zohar, Michael (1998). Lionhearts: Heroes of Israel. Warner Books. p. 187.

- ^ Derori (2005), p. 159

- ^ a b c d David Vital, Abraham Ben-Zvi, Aaron S. Klieman, Global Politics: essays in honor of David Vital (Frank Cass, 2001) p. 182

- ^ a b P. R. Kumaraswamy, The A to Z of the Arab-Israeli conflict, Scarcrow Press, Inc. (2006) p. 146

- ^ paratroopers Archived 2011-12-09 at the Wayback Machine, Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Derori (2005), p. 163

- ^ Mordechai Naor, The Twentieth Century In Eretz Israel, Konemann (1996) p. 323

- ^ a b c Shlaim, Avi: The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World (2001)

- ^ Naor, p. 328