Political repression in the Soviet Union

| Mass repression in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Economic repression |

| Political repression |

| Ideological repression |

| Ethnic repression |

Throughout the history of the Soviet Union, tens of millions of people suffered political repression, which was an instrument of the state since the October Revolution. It culminated during the Stalin era, then declined, but it continued to exist during the "Khrushchev Thaw", followed by increased persecution of Soviet dissidents during the Brezhnev era, and it did not cease to exist until late in Mikhail Gorbachev's rule when it was ended in keeping with his policies of glasnost and perestroika.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

Origins and early Soviet times

[edit]| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

Secret police had a long history in Tsarist Russia. Ivan the Terrible used the Oprichina, while more recently the Third Section and Okhrana existed.

Early on, the Leninist view of the class conflict and the resulting notion of the dictatorship of the proletariat provided the theoretical basis of the repressions. Its legal basis was formalized into the Article 58 in the code of the Russian SFSR and similar articles for other Soviet republics.[citation needed]

According to the Marxist historian Marcel Liebman, Lenin's wartime measures such as banning opposition parties was prompted by the fact that several political parties either took up arms against the new Soviet government, or participated in sabotage, collaborated with the deposed Tsarists, or made assassination attempts against Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders.[9] Liebman noted that opposition parties such as the Cadets who were democratically elected to the Soviets in some areas, then proceeded to use their mandate to welcome in Tsarist and foreign capitalist military forces.[9] In one incident in Baku, the British military, once invited in, proceeded to execute members of the Bolshevik Party who had peacefully stood down from the Soviet when they failed to win the elections. As a result, the Bolsheviks banned each opposition party when it turned against the Soviet government. In some cases, bans were lifted. This banning of parties did not have the same repressive character as later bans enforced under the Stalinist regime.[9] Trotsky also argued that he and Lenin had intended to lift the ban on the opposition parties such as the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries as soon as the economic and social conditions of Soviet Russia had improved.[10]

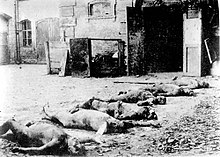

At times, the repressed were called the enemies of the people. Punishments by the state included summary executions, sending innocent people to Gulag, forced resettlement, and stripping of citizen's rights. Repression was conducted by the Cheka secret police and its successors, and other state organs. Periods of increased repression include the Red Terror, Collectivization, the Great Purges, the Doctors' Plot, and others. The secret police forces conducted massacres of prisoners on numerous occasions. Repression took place in the Soviet republics and in the territories occupied by the Soviet Army during and following World War II, including the Baltic states and Eastern Europe.[11][unreliable source?]

State repression led to incidents of popular resistance, such as the Tambov peasant rebellion (1920–1921), the Kronstadt rebellion (1921), and the Vorkuta Uprising (1953); the Soviet authorities suppressed such resistance with overwhelming military force and brutality. During the Tambov rebellion, Mikhail Tukhachevsky (chief Red Army commander in the area) authorized Bolshevik military forces to use chemical weapons against villages with civilian population and rebels.[12] Publications in local Communist newspapers openly glorified liquidations of "bandits" with the poison gas.[13] The Internal Troops of the Cheka and the Red Army practiced the terror tactics of taking and executing numerous hostages, often in connection with desertions of forcefully mobilized peasants. According to Orlando Figes, more than 1 million people deserted from the Red Army in 1918, around 2 million people deserted in 1919, and almost 4 million deserters escaped from the Red Army in 1921.[14][15]

In 1919, 612 "hardcore" deserters of the total 837,000 draft dodgers and deserters were executed following Trotsky's dracionan measures.[16] According to Figes, "a majority of deserters (most registered as "weak-willed") were handed back to the military authorities, and formed into units for transfer to one of the rear armies or directly to the front". Even those registered as "malicious" deserters were returned to the ranks when the demand for reinforcements became desperate". Forges also noted that the Red Army instituted amnesty weeks to prohibit punitive measures against desertion which encouraged the voluntary return of 98,000-132,000 deserters to the army.[17]

For a long time historians assumed that the destruction of the officer cadre of the Red Army happened during Stalin's Great Purge. However new data that emerged on the break of the 21st century radically changed this perception, [18] and the information was uncovered about the so-called Vesna Case, a massive series of Soviet repressions targeting former officers and generals of the Russian Imperial Army who had served in the Red Army and Soviet Navy, a major purge of the Red Army during 1930-1931.

Red Terror

[edit]

In his book, Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky, Trotsky also argued that the reign of terror began with the White Terror under the White Guard forces and the Bolsheviks responded with the Red Terror.[19] There is no consensus among the Western historians on the number of deaths from the Red Terror in Soviet Russia. One source gives estimates of 28,000 executions per year from December 1917 to February 1922.[20] Estimates for the number of people shot during the initial period of the Red Terror are at least 10,000.[21] Estimates for the whole period go for a low of 50,000[22] to highs of 140,000[22][23] and 200,000 executed.[24] Most estimations for the number of executions in total put the number at about 100,000.[25] However, social scientist Nikolay Zayats from the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus has argued that the figures have been greatly exaggerated due to White Army propaganda.[26]

According to Vadim Erlikhman's investigation, the number of the Red Terror's victims is at least 1,200,000 people.[27] According to Robert Conquest, a total of 140,000 people were shot in 1917–1922.[28] Candidate of Historical Sciences Nikolay Zayats states that the number of people shot by the Cheka in 1918–1922 is about 37,300 people, shot in 1918–1921 by the verdicts of the tribunals—14,200, i.e. about 50,000–55,000 people in total, although executions and atrocities were not limited to the Cheka, having been organized by the Red Army as well.[29]

In 1924, anti-Bolshevik Popular Socialist Sergei Melgunov (1879–1956) published a detailed account on the Red Terror in Russia, where he cited Professor Charles Saroléa's estimates of 1,766,188 deaths from the Bolshevik policies. He questioned the accuracy of the figures, but endorsed Saroléa's "characterisation of terror in Russia", stating it matches reality.[30][31][32] Modern historian Sergei Volkov, assessing the Red Terror as the entire repressive policy of the Bolsheviks during the years of the Civil War (1917–1922), estimates the direct death toll of the Red Terror at 2 million people.[32][33] Volkov's calculations, however, do not appear to have been confirmed by other major scholars.[35]

Collectivization

[edit]

Collectivization in the Soviet Union was a policy, pursued between 1928 and 1933, to consolidate individual land and labour into collective farms (Russian: колхо́з, kolkhoz, plural kolkhozy). The Soviet leaders were confident that the replacement of individual peasant farms by kolkhozy would immediately increase food supplies for the urban population, the supply of raw materials for processing industry, and agricultural exports generally. Collectivization was thus regarded as the solution to the crisis in agricultural distribution (mainly in grain deliveries) that had developed since 1927 and was becoming more acute as the Soviet Union pressed ahead with its ambitious industrialization program.[36] As the peasantry, with the exception of the poorest part, resisted the collectivization policy, the Soviet government resorted to harsh measures to force the farmers to collectivize. In his conversation with Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin gave his estimate of the number of "kulaks" who were repressed for resisting Soviet collectivization as 10 million, including those forcibly deported.[37][38] Recent historians have estimated the death toll in the range of six to 13 million.[39]

Great Purge

[edit]

The Great Purge (Russian: Большой террор, transliterated Bolshoy terror, The Great Terror) was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin in 1937–1938.[40][41] It involved the purge of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, repression of peasants, deportations of ethnic minorities, and the persecution of unaffiliated persons, characterized by widespread police surveillance, widespread suspicion of "saboteurs", imprisonment, and killings.[40] Estimates of the number of deaths associated with the Great Purge run from the official figure of 681,692 to nearly 1,2 million.[42][43][44][45][46]

LGBT persecution

[edit]On September 15, 1933, the deputy head of the OGPU, Genrikh Yagoda reported to Joseph Stalin about the disclosure of the "conspiracy of the homosexual community" in Moscow, Leningrad and Kharkiv. As Yagoda pointed out in the explanatory note, "the conspirators were engaged in the creation of a network of salons and other organized formations, with the subsequent transformation of these associations into direct spy cells".[47][48]

Stalin ordered "to punish the scumbags" in a demonstrative way, and to introduce a corresponding directive into the legislation. At the first stage, about 130 people were arrested who gave the necessary confessions under torture, and on December 17, 1933, the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR decided to extend criminal liability to "unnatural relationship". The article was added to the Criminal Code of the RSFSR on April 1, 1934 in the section "sexual crimes" under number 154-a. "Voluntary" sexual intercourse between two men was sentenced to three to five years in the camps, and for "cohabitation" with the use of violence - from five to eight.[49]

Nikolai Klyuev was the first known homosexual to suffer from Soviet repressions. The poet was accused of writing love lyrics that "were written from a male person to a male person." In February 1934, Klyuyev was arrested in his apartment on charges of "composing and distributing counter-revolutionary literary works", and in 1937 he was shot [50][51] [52] .[53]

In later times, the most famous victim of the Soviet repression against the LGBT was a film director Sergei Parajanov.[54]

Population transfers

[edit]

Population transfer in the Soviet Union may be divided into the following broad categories: deportations of "anti-Soviet" categories within the population, who were often classified as "enemies of the workers"; deportations of nationalities; labor force transfer; and organised migrations in opposite directions in order to fill the ethnically cleansed territories. In most cases their destinations were underpopulated and remote areas (see Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union).

Entire nations and ethnic groups were collectively punished by the Soviet government for their alleged collaboration with the enemy during World War II. At least nine distinct ethnic-linguistic groups, including ethnic Germans, ethnic Greeks, ethnic Poles, Crimean Tatars (recognized as genocide), Balkars, Chechens, and Kalmyks, were deported to remote and unpopulated areas of Siberia (see sybirak) and Kazakhstan.[55] Koreans and Romanians were also deported. Mass operations of the NKVD were needed to deport millions of people, many of whom died. According to various sources, more than 6 million people were deported, with the death toll ranging from 800,000[56] to 1,500,000[57] in the USSR only.

Gulag

[edit]

The Gulag "was the branch of the State Security that operated the penal system of forced labour camps and associated detention and transit camps and prisons. While these camps housed criminals of all types, the Gulag system has become primarily known as a place for political prisoners and as a mechanism for repressing political opposition to the Soviet state."[58][59]

Repressions in annexed territories

[edit]During the early years of World War II, the Soviet Union annexed several territories in Eastern Europe as a consequence of the German–Soviet Pact and its Secret Additional Protocol.[60]

Baltic States

[edit]

In the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, repressions and mass deportations were carried out by the Soviets. The Serov Instructions, "On the Procedure for carrying out the Deportation of Anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia", contained detailed procedures and protocols to observe in the deportation of Baltic nationals. Public tribunals were also set up to punish "traitors to the people": those who had fallen short of the "political duty" of voting their countries into the USSR. In the first year of Soviet occupation, from June 1940 to June 1941, the number confirmed executed, conscripted, or deported is estimated at a minimum of 124,467: 59,732 in Estonia, 34,250 in Latvia, and 30,485 in Lithuania.[62] This included 8 former heads of state and 38 ministers from Estonia, 3 former heads of state and 15 ministers from Latvia, and the then-president, 5 prime ministers and 24 other ministers from Lithuania.[63]

Poland

[edit]Romania

[edit]Post-Stalin era (1953–1991)

[edit]After Stalin's death, the suppression of dissent was dramatically reduced and it also took new forms. The internal critics of the system were convicted of anti-Soviet agitation, anti-Soviet slander, or they were accused of being "social parasites". Other critics were accused of being mentally ill, they were accused of having sluggish schizophrenia and incarcerated in "psikhushkas", i.e. mental hospitals which were used as prisons by the Soviet authorities.[64] A number of notable dissidents, including Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Vladimir Bukovsky, and Andrei Sakharov, were sent to internal or external exile.

Loss of life

[edit]

Estimates of the number of deaths attributable specifically to Joseph Stalin vary widely. Some scholars assert that record-keeping of the executions of political prisoners and ethnic minorities are neither reliable nor complete;[65] others contend archival materials contain irrefutable data far superior to sources utilized prior to 1991, such as statements from emigres and other informants.[66][67] Those historians working after the Soviet Union's dissolution have estimated victim totals ranging from approximately 3 million[68] to nearly 9 million.[69] Some scholars still assert that the death toll could be in the tens of millions.[70]

American historian Richard Pipes noted: "Censuses revealed that between 1932 and 1939—that is, after collectivization but before World War II—the population decreased by 9 to 10 million people.[71] In his most recent edition of The Great Terror (2007), Robert Conquest states that while exact numbers may never be known with complete certainty, at least 15 million people were killed "by the whole range of Soviet regime's terrors".[28] Rudolph Rummel in 2006 said that the earlier higher victim total estimates are correct, although he includes those killed by the government of the Soviet Union in other Eastern European countries as well.[72] Conversely, J. Arch Getty and Stephen G. Wheatcroft insist that the opening of the Soviet archives has vindicated the lower estimates put forth by "revisionist" scholars.[68][73] Simon Sebag Montefiore in 2003 suggested that Stalin was ultimately responsible for the deaths of at least 20 million people.[74]

Some of these estimates rely in part on demographic losses. Conquest explained how he arrived at his estimate: "I suggest about eleven million by the beginning of 1937, and about three million over the period 1937–38, making fourteen million. The eleven-odd million is readily deduced from the undisputed population deficit shown in the suppressed census of January 1937, of fifteen to sixteen million, by making reasonable assumptions about how this was divided between birth deficit and deaths."[75]

Australian historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft claims that prior to the opening of the archives for historical research, "our understanding of the scale and the nature of Soviet repression has been extremely poor" and that some specialists who wish to maintain earlier high estimates of the Stalinist death toll are "finding it difficult to adapt to the new circumstances when the archives are open and when there are plenty of irrefutable data" and instead "hang on to their old Sovietological methods with round-about calculations based on odd statements from emigres and other informants who are supposed to have superior knowledge."[66][67] Conversely, some historians believe that the official archival figures of the categories that were recorded by Soviet authorities are unreliable and incomplete.[65] In addition to failures regarding comprehensive recordings, as one additional example, Canadian historian Robert Gellately and British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore argue that the many suspects beaten and tortured to death while in "investigative custody" were likely not to have been counted amongst the executed.[67]

| Event | Deaths | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1- Red Terror | 50,000 – 2,000,000 | [76][77][30] |

| 2- Dekulakization | 389,521 – 5,000,000 | [78][79] |

| 3- Gulag | 1,053,829 - 2,500,000 | [68][80] |

| 4- Great Purge | 683,692 – 1,200,000 | [68][81] |

| 5- Deportation of national minorities | 450,000 – 1,500,000 | [82][83][57] |

| A- Repression outside of famine | 2,627,042 – 12,200,000 | Sum of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 above |

| 6- Russian famine of 1921–1922 | 1,000,000 – 5,000,000 | [84][85] |

| 7- Soviet famine of 1930–1933 | 5,700,000 – 8,700,000 | [86][87][88] |

| 8- Soviet famine of 1946–1947 | 500,000 - 2,000,000 | [89]: 233 [90] |

| B- Famine deaths | 7,200,000 – 15,700,000 | Sum of 6 and 7 above |

| Total | 9,827,042 – 27,900,000 | Sum of A and B above |

Remembering the victims

[edit]

A Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Political Repression (День памяти жертв политических репрессий) has been officially held on 30 October in Russia since 1991. It is also marked in other former Soviet republics except Ukraine, which has its own annual Day of Remembrance for the victims of political repressions by the Soviet regime, held each year on the third Sunday of May.

Members of the Memorial society took an active part in such commemorative meetings.[citation needed] Since 2007, Memorial had also organised the day-long "Restoring the Names" ceremony at the Solovetsky Stone in Moscow every 29 October.[91] The organization was banned by the Russian government in 2022.[92][93][94] Some of Memorial's human rights activities have continued in Russia.[95]

The Wall of Grief in Moscow, inaugurated in October 2017, is Russia's first monument ordered by presidential decree for people killed during the Stalinist repressions in the Soviet Union.[96][97]

See also

[edit]- Active measures

- Crimes against humanity under communist regimes

- Criticism of communist party rule

- Goli Otok

- Hitler Youth conspiracy

- Human rights in the Soviet Union

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

- Persecution of Christians in the Eastern Bloc

- Political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union

- Rehabilitation (Soviet)

- Law of the Soviet Union

- Politics of the Soviet Union

- Soviet repressions in Belarus

- The Black Book of Communism

- Anti-religious campaign during the Russian Civil War (1917–1921)

- RSFSR and USSR anti-religious campaign (1921–1928)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1958–1964)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1970s–1987)

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Past political repression creates long-lasting mistrust". 2 March 2022.

- ^ "How Lenin's Red Terror set a macabre course for the Soviet Union". National Geographic Society. 2 September 2020. Archived from the original on February 22, 2021.

- ^ "How the 'Red Terror' Exposed the True Turmoil of Soviet Russia 100 Years Ago". 5 September 2018.

- ^ Livi-Bacci, Massimo (1993). "On the Human Costs of Collectivization in the Soviet Union". Population and Development Review. 19 (4): 743–766. doi:10.2307/2938412. JSTOR 2938412.

- ^ Viola, Lynne (1986). "The Campaign to Eliminate the Kulak as a Class, Winter 1929-1930: A Reevaluation of the Legislation". Slavic Review. 45 (3): 503–524. doi:10.2307/2499054. JSTOR 2499054. S2CID 159758939.

- ^ "The Soviet Massive Deportations - A Chronology | Sciences Po Violence de masse et Résistance – Réseau de recherche". 18 April 2019.

- ^ "Great Purge | History & Facts | Britannica". 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Gulag | Definition, History, Prison, & Facts | Britannica". 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Liebman, Marcel (1985). Leninism Under Lenin. Merlin Press. pp. 1–348. ISBN 978-0-85036-261-9.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (5 January 2015). The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky. Verso Books. p. 528. ISBN 978-1-78168-721-5.

- ^ Anton Antonov-Ovseenko Beria (Russian) Moscow, AST, 1999. Russian text online

- ^ Mayer 2002, p. 395; Werth 1999, p. 117.

- ^ Figes 1997, p. 768; Pipes 2011, pp. 387–401.

- ^ Figes (1997), Chapter 13.

- ^ Courtois et al, 1999: [page needed]

- ^ Reese, Roger R. (3 October 2023). Russia's Army: A History from the Napoleonic Wars to the War in Ukraine. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8061-9356-4.

- ^ Figes, Orlando (1990). "The Red Army and Mass Mobilization during the Russian Civil War 1918-1920". Past & Present (129): 168–211. doi:10.1093/past/129.1.168. ISSN 0031-2746. JSTOR 650938.

- ^ Операция «Весна», Znanie — Sila magazine, no. 11, 2003

- ^ Kline, George L (1992). In Defence of Terrorism in The Trotsky reappraisal. Brotherstone, Terence; Dukes, Paul,(eds). Edinburgh University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7486-0317-6.

- ^ Ryan (2012), p. 2.

- ^ Ryan (2012), p. 114.

- ^ a b Stone, Bailey (2013). The Anatomy of Revolution Revisited: A Comparative Analysis of England, France, and Russia. Cambridge University Press. p. 335.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (2011). The Russian Revolution. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 838.

- ^ Lowe (2002), p. 151.

- ^ Lincoln, W. Bruce (1989). Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War. Simon & Schuster. p. 384. ISBN 0-671-63166-7.

... the best estimates set the probable number of executions at about a hundred thousand.

- ^ "On the scale of the Red Terror during the Civil War". scepsis.net.

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. Потери народонаселения в XX веке.: Справочник — М.: Издательский дом «Русская панорама», 2004. — ISBN 5-93165-107-1

- ^ a b Conquest, Robert (2007). The Great Terror: A Reassessment, 40th Anniversary Edition. Oxford University Press. pp. in Preface, p. xvi: "Exact numbers may never be known with complete certainty, but the total of deaths caused by the whole range of Soviet regime's terrors can hardly be lower than some fifteen million.".

- ^ К вопросу о масштабах красного террора в годы Гражданской войны

- ^ a b Часть IV. На гражданской войнe. // Sergei Melgunov «Красный террор» в России 1918–1923. — 2-ое изд., доп. — Берлин, 1924

- ^ Melgunov, Sergei Petrovich (2008) [1924]. Der rote Terror in Russland 1918–1923 (reprint of the 1924 Olga Diakow edition) (in German). Berlin: OEZ. p. 186, note 182. ISBN 978-3-940452-47-4. An online English translation of the second edition of Melgunov's work is accessible at Internet Archive, whence the following translated text is drawn (p. 85, note n. 128): "Professor Sarolea, who published a series of articles about Russia in Edinburgh newspaper “The Scotsman” touched upon the death statistics in an essay on terror (No. 7, November 1923.). He summarized the outcome of the Bolshevik massacre as follows: 28 bishops, 1219 clergy, 6000 professors and teachers, 9000 doctors, 54,000 officers, 260,000 soldiers, 70,000 policemen, 12,950 landowners, 355,250 professionals, 193,290 workers, 815,000 peasants. The author did not provide the sources of that data. Needless to say that the precise counts seem [too] fictional, but the author's [characterisation] of terror in Russia in general matches reality."

- ^ a b Перевощиков А. (August 2010). "Генетическому фонду России был нанесен чудовищный, не восполненный до сего времени, урон". Официальный сайт Московского регионального отделения движения "Народный собор". Archived from the original on 2010-09-11. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ Timofeychev, Alexey (7 September 2018). "How many lives did the Red Terror claim?". Russia Beyond. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Graziosi (2007), pp. 171 & 570.

- ^ In particular, they seem quite at odds with the demographic considerations elaborated by Italian historian and professor Andrea Graziosi in the light of the good quality Tsarist and early Soviet statistics. According to him, the excess deaths between 1914 and 1922 were about 16 million, of which 4–5 were military, the rest civilian. The overwhelming majority of the latter resulted from "starvation, typhus, epidemics, the Spanish flu and the famine of 1921-22", the roughly number of "victims of the various kinds of terror, and red and white repressions" amounting to a few hundred thousand— albeit a dreadful number in itself.[34]

- ^ Davies, R.W., The Soviet Collective Farms, 1929–1930, Macmillan, London (1980), p. 1.

- ^ Valentin Berezhkov, "Kak ya stal perevodchikom Stalina", Moscow, DEM, 1993, ISBN 5-85207-044-0. p. 317

- ^ Stanislav Kulchytsky, "How many of us perished in Holodomor in 1933" Archived 2006-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, Zerkalo Nedeli, November 23–29, 2002.

- ^ Constantin Iordachi; Arnd Bauerkamper (2014). The Collectivization of Agriculture in Communist Eastern Europe: Comparison and Entanglements. Central European University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9786155225635.

- ^ a b Figes, 2007: pp. 227–315

- ^ Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. By Robert Gellately. 2007. Knopf. 720 pages ISBN 1-4000-4005-1

- ^ "Introduction: the Great Purges as history", Origins of the Great Purges, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–9, 1985, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511572616.002, ISBN 978-0521259217, retrieved 2021-12-02

- ^ Homkes, Brett (2004). "Certainty, Probability, and Stalin's Great Purge". McNair Scholars Journal.

- ^ Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments". Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1151–1172. ISSN 0966-8136. JSTOR 826310.

- ^ Shearer, David R. (11 September 2023). Stalin and War, 1918-1953: Patterns of Repression, Mobilization, and External Threat. Taylor & Francis. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-000-95544-6.

- ^ Nelson, Todd H. (16 October 2019). Bringing Stalin Back In: Memory Politics and the Creation of a Useable Past in Putin's Russia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4985-9153-9.

- ^ Игорь Кон. Лики и маски однополой любви: лунный свет на заре

- ^ Как в СССР преследовали гомосексуалов - история, фото

- ^ Дэн Хили. Гомосексуальное влечение в революционной России: регулирование сексуально-гендерного диссидентства = Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent / науч. ред. Л. В. Бессмертных, Ю. А. Михайлов, пер. с англ. Т .Ю. Логачева, В. И. Новиков. — Москва: НИЦ «Ладомир», 2008. — 624 с. — (Русская потаенная литература). — 1000 экз.

- ^ "Возлюбленный - камень, где тысячи граней...". Николай Клюев

- ^ З. Дичаров. Николай Алексеевич Клюев // «Писатели Ленинграда»

- ^ Русские писатели XX века. — М.: 2000. С. 346

- ^ Николай Клюев. Сердце Единорога. Стихотворения и поэмы. — СПб.: РХГИ, 1999. — С. 9—67. — 1072 с.

- ^ СЛЕДЫ КГБ И ЩЕРБИЦКОГО В ДЕЛЕ ПАРАДЖАНОВА

- ^ Conquest, 1986: [page needed]

- ^ Grieb 2014, p. 930.

- ^ a b Werth 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Anne Applebaum (2003). Gulag: A History. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0767900560.

- ^ Robert Service (June 7, 2003). "The accountancy of pain". The Guardian.

- ^ The Soviet occupation and incorporation at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Roszkowski, Wojciech (2016). Biographical Dictionary of Central and Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 2549. ISBN 978-1317475934.

- ^ Dunsdorfs, Edgars. The Baltic Dilemma. Speller & Sons, New York. 1975

- ^ Küng, Andres. Communism and Crimes against Humanity in the Baltic States. 1999 "Communism and Crimes against Humanity in the Baltic states". Archived from the original on 2001-03-01. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- ^ "Dangerous Minds". www.hrw.org.

- ^ a b "SOVIET STUDIES". sovietinfo.tripod.com. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- ^ a b Wheatcroft, S. G. (1996). "The Scale and Nature of German and Soviet Repression and Mass Killings, 1930–45" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 48 (8): 1319–1353. doi:10.1080/09668139608412415. JSTOR 152781.

- ^ a b c Wheatcroft, S. G. (2000). "The Scale and Nature of Stalinist Repression and its Demographic Significance: On Comments by Keep and Conquest" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 52 (6): 1143–1159. doi:10.1080/09668130050143860. PMID 19326595. S2CID 205667754.

- ^ a b c d Getty, J. Arch; Rittersporn, Gábor; Zemskov, Viktor (1993). "Victims of the Soviet penal system in the pre-war years: a first approach on the basis of archival evidence" (PDF). American Historical Review. 98 (4): 1022. doi:10.2307/2166597. JSTOR 2166597.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2011-01-27). "Hitler vs. Stalin: Who Was Worse?". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- ^ Rosefielde, Steven (2008). Red Holocaust. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-415-77757-5.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (2001). Communism: A History. USA. p. 67.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "How Many Did Stalin Really Murder? | The Distributed Republic". www.distributedrepublic.net. Archived from the original on 2017-09-30. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- ^ Wheatcroft, S. G. (1999). "Victims of Stalinism and the Soviet Secret Police: The Comparability and Reliability of the Archival Data. Not the Last Word" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 51 (2): 315–345. doi:10.1080/09668139999056.

- ^ Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2007-12-18). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 643. ISBN 9780307427939.

- ^ Conquest, Robert (October 1996). "Robert Conquest, Excess Deaths in the Soviet Union, NLR I/219, September–October 1996". New Left Review (I/219): 143. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- ^ Stone, Bailey (2013). The Anatomy of Revolution Revisited: A Comparative Analysis of England, France, and Russia. Cambridge University Press. p. 335.

- ^ Lowe, Norman (2002). Mastering Twentieth Century Russian History. Palgrave. ISBN 9780333963074. p. 151

- ^ Pohl, J. Otto (1999). Ethnic Cleansing in the USSR, 1937–1949. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30921-2. LCCN 98-046822 p. 46

- ^ Hildermeier, Manfred (2016). Die Sowjetunion 1917–1991. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 35. ISBN 978-3486855548.

- ^ Nakonechnyi, Mikhail (2020). 'Factory of invalids': Mortality, disability and early release on medical grounds in GULAG, 1930–1955 (Thesis). University of Oxford.

- ^ Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1151–1172. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177. S2CID 43510161.

The best estimate that can currently be made of the number of repression deaths in 1937–38 is the range 950,000–1.2 million, i.e. about a million. This is the estimate which should be used by historians, teachers and journalists concerned with twentieth century Russian—and world—history

- ^ Buckley, Cynthia J.; Ruble, Blair A.; Hofmann, Erin Trouth (2008). Migration, Homeland, and Belonging in Eurasia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0801890758. LCCN 2008-015571.

- ^ Grieb, Christiane (2014). "Warsaw, Battle for". In C. Dowling, Timothy (ed.). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598849486. LCCN 2014017775. p.930

- ^ Bertrand M. Patenaude. The Big Show in Bololand. The American Relief Expedition to Soviet Russia in the Famine of 1921. Stanford University Press, 2002. p. 197.

- ^ Norman Lowe. Mastering Twentieth-Century Russian History. Palgrave, 2002. p. 155.

- ^ Davies, Robert W.; Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2009). The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931–1933. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 415. doi:10.1057/9780230273979. ISBN 9780230238558.

- ^ Rosefielde, Steven (September 1996). "Stalinism in Post-Communist Perspective: New Evidence on Killings, Forced Labour and Economic Growth in the 1930s". Europe-Asia Studies. 48 (6): 959–987. doi:10.1080/09668139608412393.

- ^ Wolowyna, Oleh (October 2020). "A Demographic Framework for the 1932–1934 Famine in the Soviet Union". Journal of Genocide Research. 23 (4): 501–526. doi:10.1080/14623528.2020.1834741. S2CID 226316468.

- ^ Werth, Nicolas (2015). "Apogee and Crisis in the Gulag System". In Courtois, Stephane (ed.). Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-5882380556. OCLC 929124088.

- ^ Ganson, Nicholas (2009). "Introduction: Famine of Victors". The Soviet Famine of 1946–1947 in Global and Historical Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. xii–xix. ISBN 9780230613331.

- ^ "Restoring the Names, Dmitriev Affair website, 30 October 2017.

- ^ "Russia: Dissolution of Human Rights Center "Memorial" confirmed in…". OMCT. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "The Organization Has Been Liquidated by a Court Decision". Memorial Society. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Chernova, Anna. "Historic Russian Human Rights Center Closes, Warns of "Return to the Totalitarian Past"". CNN. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Старикова, М. (7 April 2022). ""Мемориал" после ликвидации объявил о старте нового проекта" [after the liquidation, "Memorial" announced the start of a new project] (in Russian). Коммерсантъ. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Путин открыл в Москве мемориал "Стена скорби"" [Putin Opened the Memorial "Wall of Grief" in Moscow]. РБК (in Russian). 30 October 2017.

- ^ "Wall of Grief: Putin opens first Soviet victims memorial". BBC News. 30 October 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Conquest, Robert (1986). The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505180-3.

- Courtois, Stephane; et al., eds. (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2.

- Figes, Orlando (2007). The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-7461-1.

- Getty, J. Arch; Rittersporn, Gábor; Zemskov, Viktor (1993). "Victims of the Soviet penal system in the pre-war years: a first approach on the basis of archival evidence" (PDF). American Historical Review. 98 (4): 1022. doi:10.2307/2166597. JSTOR 2166597.

- Grieb, Christiane (2014). "War Crimes, Soviet, World War II". In C. Dowling, Timothy (ed.). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598849486. LCCN 2014017775.

- Lindy, Jacob D.; Lifton, Robert Jay (2001). Beyond invisible walls: the psychological legacy of Soviet trauma, East European therapists, and their patients. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-58391-318-5.

- Lowe, Norman (2002). Mastering Twentieth Century Russian History. Palgrave. ISBN 9780333963074.

- "New directions in Gulag studies: a roundtable discussion," Canadian Slavonic Papers 59, no 3-4 (2017)

- Nove, Alec (1993). "Victims of Stalinism: How Many?". In Getty, J. Arch; Manning, Roberta T. (eds.). Stalinist Terror: New Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44670-9.

- Ryan, James (2012). Lenin's Terror: The Ideological Origins of Early Soviet State Violence. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1138815681.

- Wheatcroft, Stephen (1996). "The Scale and Nature of German and Soviet Repression and Mass Killings, 1930–45" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 48 (8): 1319–1353. doi:10.1080/09668139608412415. JSTOR 152781.

- Wheatcroft, S. G. (2000). "The Scale and Nature of Stalinist Repression and its Demographic Significance: On Comments by Keep and Conquest" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 52 (6): 1143–1159. doi:10.1080/09668130050143860. PMID 19326595. S2CID 205667754.

- Lynne Viola, "New sources on Soviet perpetrators of mass repression: a research note," Canadian Slavonic Papers 60, no 3-4 (2018)

- Figes, Orlando (1997). A People's Tragedy. New York: Viking Press. pp. 753–769. ISBN 0670859168.

- Mayer, Arno J. (2002). The Furies: Violence and Terror in the French and Russian Revolutions. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09015-3.

- Pipes, Richard (2011). Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-78861-0.

- Werth, Nicolas (1999). "A State against Its People: Violence, Repression, and Terror in the Soviet Union". The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. pp. 33–268. ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2.

- Werth, Nicolas (2004). "Strategies of Violence in the Stalinist USSR". In Rousso, Henry; Golsan, Richard Joseph (eds.). Stalinism and Nazism: History and Memory Compared. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803290006. LCCN 2003026805.

Further reading

[edit]- Brooks, Jeffrey (2000). Thank you, comrade Stalin!: Soviet public culture from revolution to Cold War. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00411-2.

- Davies, Robert; Wheatcroft, Stephen (2009). The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia Volume 5: The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931–1933. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-230-27397-9.

- Ellman, Michael (November 2002). "Soviet repression statistics: some comments". Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1151–1172. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177. S2CID 43510161.

- Eremina, Larisa; Roginsky, Arseny [Лариса Еремина, Арсений Рогинский] (2002). Расстрельные списки: Москва, 1937–1941: "Коммунарка", Бутово: книга памяти жертв политических репрессий [Shot lists: Moscow, 1937–1941: "Kommunarka", Butovo: the book for commemoration of political repression victims] (in Russian). Moscow: Memorial. ISBN 978-5787000597.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Eremina, Larisa; Roginsky, Arseny [Лариса Еремина, Арсений Рогинский] (2005). Расстрельные списки: Москва, 1935–1953: Донское кладбище (Донской крематорий): книга памяти жертв политических репрессий [Shot lists: Moscow, 1935–1953: the Donskoye cemetery (the Donskoy crematorium): the book for commemoration of political repression victims] (in Russian). Moscow: Memorial. ISBN 978-5787000818.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Haynes, Michael; Husan, Rumy (2003). A Century Of State Murder? Death and Policy in Twentieth Century Russia. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745319308.

- Johns, Michael (Fall 1987). "Seventy years of evil: Soviet crimes from Lenin to Gorbachev". Policy Review: 10–23.

- Leggett, George (1981). The Cheka: Lenin's Political Police. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822862-2.

- Medvedev, Roy Aleksandrovich (1985). On Soviet Dissent. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-04813-2.

- Rosefielde, Steven (2009). Red Holocaust. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-77757-5.

- Samatan, Marie (1980). Droits de l'homme et répression en URSS: l'appareil et les victimes [Human rights and repression in the USSR: mechanism and victims] (in French). Paris: Seuil. ISBN 978-2020057059.

- Shearer, David R. (2009). Policing Stalin's socialism: repression and social order in the Soviet Union, 1924–1953. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14925-8.

- Solomon, Peter H. (1996). Soviet criminal justice under Stalin. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56451-9.

- Wintrobe, Ronald (2000). The Political Economy of Dictatorship. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79449-7.

- Александр Подрабинек (2015). Наша кампания за амнистию [Our campaign for amnesty]. Zvezda (in Russian) (4). Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Zhanbosinova, Albina [Альбина Жанбосинова] (2013). "Политические репрессии в СССР (1920–1950 гг.): историко-статистическое исследование" [Political repression in the USSR (1920–1950s): historical and statistical research] (PDF). European Researcher (in Russian). 45 (4–1): 811–822. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2015.

- "Political repressions in the USSR". The Andrei Sakharov Museum and Public Center. Archived from the original on 2016-02-14. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

External links

[edit] Media related to Political repression in the Soviet Union at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Political repression in the Soviet Union at Wikimedia Commons