Presidency of James K. Polk

| |

| Presidency of James K. Polk March 4, 1845 – March 4, 1849 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | Democratic |

| Election | 1844 |

| Seat | White House |

|

| |

The presidency of James K. Polk began on March 4, 1845, when James K. Polk was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1849. He was a Democrat, and assumed office after defeating Whig Henry Clay in the 1844 presidential election. Polk left office after one term, fulfilling a campaign pledge he made in 1844, and he was succeeded by Whig Zachary Taylor. A close ally of Andrew Jackson, Polk's presidency reflected his adherence to the ideals of Jacksonian democracy and manifest destiny.

Polk was the last strong pre-Civil War president, having met during his four years in office every major domestic and foreign policy goal set during his campaign and the transition to his administration. Polk's presidency was particularly influential in U.S. foreign policy, and his presidency saw the last major expansions of the Contiguous United States. When Mexico rejected the U.S. annexation of Texas, Polk achieved a sweeping victory in the Mexican–American War, which resulted in the cession by Mexico of nearly the whole of what is now the American Southwest. He threatened war with Great Britain over control of the Oregon Country, eventually reaching an agreement in which both nations agreed to partition the region at the 49th parallel.

Polk also accomplished his goals in domestic policy. He ensured a substantial reduction of tariff rates by replacing the "Black Tariff" with the Walker tariff of 1846, which pleased the less-industrialized states of his native Southern United States by rendering less expensive both imported and, through competition, domestic goods. Additionally, he built an independent treasury system that lasted until 1913, oversaw the opening of the U.S. Naval Academy and of the Smithsonian Institution, the groundbreaking for the Washington Monument, and the issuance of the first United States postage stamp.

Polk did not closely involve himself in the 1848 presidential election, but his actions strongly affected the race. General Zachary Taylor, who had served in the Mexican–American War, won the Whig presidential nomination and defeated Polk's preferred candidate, Democratic Senator Lewis Cass. Scholars have ranked Polk favorably for his ability to promote, obtain support for, and achieve all of the major items on his presidential agenda. However, he has also been criticized for leading the country into war against Mexico and for exacerbating sectional divides. Polk has been called the "least known consequential president" of the United States.[1]

1844 election[edit]

In the months leading up to the 1844 Democratic National Convention, former President Martin Van Buren was widely seen as the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination. Polk, who desired to be the party's vice-presidential nominee in the 1844 election,[2] engaged in a delicate and subtle campaign to become Van Buren's running mate.[3] The proposed annexation of the Republic of Texas by President John Tyler upended the presidential race. Van Buren and the Whig frontrunner, Henry Clay, opposed the annexation and a potential war with Mexico over the disputed territory,[4] Polk and former President Andrew Jackson strongly supported the acquisition of the independent country.[5] Disappointed by Van Buren's position, Jackson threw his support behind Polk for the nomination.[6]

When the Democratic National Convention began on May 27, 1844, the key question was whether the convention would adopt a rule requiring the presidential nominee to receive the vote of two-thirds of the delegates.[7] With the strong support of the Southern states, the two thirds-rule was passed by the convention, effectively ending the possibility of Van Buren's nomination due to the strong opposition he faced from an unyielding and significant minority of delegates.[8] Van Buren won a majority on the first presidential ballot, but failed to win the necessary super-majority, and support for Van Buren faded on subsequent ballots.[8] On the eighth presidential ballot, Polk won 44 of the 266 delegates, as support for all candidates other than Polk, Lewis Cass, and Van Buren dissipated.[9] Following the eighth ballot, several delegates rose to speak in support of Polk's candidacy.[9] Van Buren, then realizing that he had no chance of ever winning the 1844 presidential nomination, threw his support behind Polk, who won on the next ballot. In doing so, Polk became the first "dark horse" candidate ever to win a major U.S. political party's presidential nomination.[10] After Senator Silas Wright, a close Van Buren ally, declined the vice presidential nomination, the convention nominated former Senator George M. Dallas of Pennsylvania as Polk's running mate.[11]

After learning of his nomination, Polk promised to serve only one term, believing that this would help him win the support of Democratic leaders such as Cass, Wright, John C. Calhoun, Thomas Hart Benton, and James Buchanan, all of whom had presidential aspirations.[12][13] Further, he avoided taking a position on the protectionist Tariff of 1842, but appealed to the key state of Pennsylvania by using rhetoric favorable towards high tariffs.[14] In New York, another key swing state, Polk's campaign was greatly aided by the gubernatorial candidacy of Wright, who managed to unite the factions of the New York Democratic Party.[14]

The abolitionist Liberty party nominated Michigan's James G. Birney,[15] while the 1844 Whig National Convention nominated Henry Clay on the first ballot. Notwithstanding that Polk had been Speaker of the House of Representatives and governor of Tennessee, Whig speeches and editorials scorned Polk, mocking him with the chant "Who is James K. Polk?" in reference to Polk's relative obscurity compared to both Van Buren or Clay.[16] The Whigs blanketed the nation with hundreds of thousands of anti-Polk tracts, accusing him of being a puppet of the "slaveocracy" and a radical who would destroy the United States over the annexation of Texas.[10] Democrats like Robert Walker recast the issue of Texas annexation, arguing that Texas and as Oregon were rightfully American but had been lost during the Monroe administration. Walker further argued that Texas would provide a market for Northern goods and would allow for the "diffusion" of slavery, which in turn would lead to gradual emancipation.[17] In response, Clay argued that the annexation of Texas would bring war with Mexico and increase sectional tensions.[18]

Ultimately, Polk triumphed in an extremely close election, defeating Clay 170–105 in the Electoral College; the flip of just a few thousand voters in New York would have given the election to Clay.[19] Birney won several thousand anti-annexation votes in New York, and his presence in the race may have cost Clay the election.[20]

Inauguration[edit]

Polk was inaugurated as the nation's 11th president on March 4, 1845, in a ceremony held on the East Portico of the United States Capitol. Chief Justice Roger Taney administered the oath of office. Polk's inauguration was the first presidential inauguration to be reported by telegraph and shown in a newspaper illustration (in The Illustrated London News).[21]

Polk's inaugural address, written with the help of Amos Kendall, was a message of hope and confidence. At 4,476 words, it is the second longest inaugural address, behind only that of William Henry Harrison. In his inaugural address, Polk touched on the Jacksonian principles that had guided his political career and Democratic Party positions that would guide his administration. A major theme of the speech was the nation's westward expansion. He detailed how important the addition of Texas to the Union was, and noted that Americans were moving into lands even further west (California and Oregon).[22] He declared:

But eighty years ago our population was confined on the west by the ridge of the Alleghanies. Within that period—within the lifetime, I might say, of some of my hearers—our people, increasing to many millions, have filled the eastern valley of the Mississippi, adventurously ascended the Missouri to its headsprings, and are already engaged in establishing the blessings of self-government in valleys of which the rivers flow to the Pacific.[23]

At the time that Polk became president, the nation's population had doubled every twenty years since the American Revolution and had reached demographic parity with Britain.[24] Polk's tenure saw continued technological improvements, including the expansion of railroads and increased use of the telegraph.[24] These improved communications and growing demographics increasingly made the United States into a strong military power, and also stoked expansionism.[25]

Administration[edit]

Cabinet[edit]

| The Polk cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | James K. Polk | 1845–1849 |

| Vice President | George M. Dallas | 1845–1849 |

| Secretary of State | James Buchanan | 1845–1849 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Robert J. Walker | 1845–1849 |

| Secretary of War | William L. Marcy | 1845–1849 |

| Attorney General | John Y. Mason | 1845–1846 |

| Nathan Clifford | 1846–1848 | |

| Isaac Toucey | 1848–1849 | |

| Postmaster General | Cave Johnson | 1845–1849 |

| Secretary of the Navy | George Bancroft | 1845–1846 |

| John Y. Mason | 1846–1849 | |

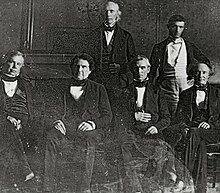

Polk governed with the help of his cabinet, in which he placed great importance. The cabinet regularly met twice a week, and Polk and his six cabinet members discussed all major issues during these meetings.[26] Despite his reliance on his cabinet, Polk involved himself in the minutiae of the various departments, especially regarding the military.[27]

In selecting a new cabinet, Polk generally heeded Jackson's advice to avoid individuals who were themselves interested in the presidency, though he chose to nominate Buchanan for the crucial and prestigious position of Secretary of State.[28][29] Polk respected Buchanan's opinion and Buchanan played an important role in Polk's presidency, but the two often clashed over foreign policy and appointments.[30] Polk frequently considered dismissing Buchanan from office, as he suspected Buchanan of placing his own presidential aspirations above service to Polk, but Buchanan always managed to convince Polk of his loyalty.[31]

Polk put together an initial slate of cabinet choices that met with the approval of Andrew Jackson, who Polk met with in January 1845 for the last time, as Jackson died in June 1845.[32] Cave Johnson, a close friend and ally of Polk, would be nominated for the position of Postmaster General.[32] Though Polk was personally close with the incumbent Navy Secretary, John Y. Mason, he replaced him after Jackson insisted that none of Tyler's cabinet be retained.[32] In his place, Polk selected George Bancroft, a historian who had played a crucial role in Polk's nomination.[32] Polk also selected Senator Robert J. Walker of Mississippi as Attorney General.[32]

However, after news of Buchanan's selection for State was leaked, Vice President Dallas (an in-state rival of Buchanan) and a slew of Southerners insisted that Walker receive the higher position at Treasury.[33] Polk instead chose to nominate Bancroft as a compromise at Treasury while nominating Mason as Attorney General and a New Yorker, William L. Marcy, as Secretary of War.[33] Polk had intended the Marcy appointment to mollify Van Buren, but Van Buren was outraged at the move, in part due to Marcy's affiliation with the rival "Hunker" faction.[33] Polk then further enraged Van Buren by finally choosing Walker for Treasury; Bancroft was shifted back to Navy Secretary.[34]

After the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, Polk shook up his cabinet, sending Bancroft to Great Britain as an ambassador, shifting Mason to his old position of Navy Secretary, and successfully nominating Nathan Clifford as Attorney General.[35]

Goals[edit]

According to a story told decades later by George Bancroft, Polk set four clearly defined goals for his administration:[25]

- Reestablish the Independent Treasury System.

- Reduce tariffs.

- Acquire some or all of Oregon Country.

- Acquire California and New Mexico from Mexico.

While his domestic aims represented continuity with past Democratic policies, successful completion of Polk's foreign policy goals would represent the first major American territorial gains since the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.[25]

Judicial appointments[edit]

The 1844 death of Justice Henry Baldwin had created a vacancy on the Supreme Court, and Tyler's failure to fill the seat left a Supreme Court seat open when Polk took office. Polk's attempt to fill Baldwin's seat became embroiled in Pennsylvania politics and the efforts of factional leaders to secure the lucrative post of Collector of Customs for the Port of Philadelphia. As Polk sought to find his way through the minefield of Pennsylvania politics, a second position on the high court became vacant with the death, in September 1845, of Justice Joseph Story; his replacement was expected to come from his native New England. Because Story's death had occurred while the Senate was not in session, Polk was able to make a recess appointment, choosing Senator Levi Woodbury of New Hampshire, and when the Senate reconvened in December 1845, the Senate confirmed the appointment of Woodbury. Polk's initial nominee for Baldwin's seat, George W. Woodward, was rejected by the Senate in January 1846, in large part due to the opposition of Buchanan and Pennsylvania Senator Simon Cameron.[36][37]

Polk eventually offered Buchanan the open seat, but Buchanan, after some indecision, turned it down. Polk subsequently nominated Robert Cooper Grier, who won confirmation.[38] Justice Woodbury served until his death in 1851,[39] but Grier served until 1870. In the slavery case of Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), Grier wrote an opinion stating that slaves were property and could not sue.[40]

Polk appointed eight other federal judges, one to the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, and seven to various United States district courts.[41]

Foreign affairs[edit]

Polk's main achievements in foreign policy were:

- Oregon Boundary: Polk successfully resolved the long-standing dispute between the United States and Britain over the Oregon Country (modern-day Oregon, Washington, and parts of Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana). Through diplomatic negotiations, Washington and London agreed to the 49th parallel as the boundary line, securing American control over present-day Oregon and Washington.

- Annexation of Texas: President Polk was a strong advocate for the annexation of Texas, which had been independent from Mexico in 1836. He successfully pushed for the admission of Texas as a state in 1845, expanding the territory of the United States and fulfilling a main goal of manifest destiny.

- Victory against Mexico. The U.S. military, under Polk's direction, achieved a series of military victories without major defeats. This led to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. The Treaty secured vast territories for the United States, including California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. Acquisition of Texas and California were Polk's original goals.

- Reduction of Tariffs: Polk successfully advocated for the low tariffs. The Walker Tariff of 1846, named after Polk's Treasury Secretary Robert J. Walker, significantly reduced import duties. This policy change aimed to lower prices paid by American consumers.

The United States added more territory during the one term administration of President Polk than during any other president's administration.[42]

Annexation of Texas[edit]

The Republic of Texas had gained independence from Mexico following the Texas Revolution of 1836, and, partly because Texas had been settled by a large number of Americans, there was a strong sentiment in both Texas and the United States for the annexation of Texas by the United States. During the transition period after the 1844 election, President Tyler sought to complete the annexation of Texas. Lacking a two-thirds majority, an earlier treaty that would annex the republic was defeated in the Senate. Tyler proposed that Congress accomplish annexation through a joint resolution.[43] Due to disagreements regarding the extension of slavery, Senator Benton of Missouri and Secretary of State Calhoun disagreed on the best way to annex Texas, and Polk became involved in negotiations to break the impasse.[43] With Polk's help, the annexation resolution narrowly cleared the Senate.[43]

In a surprise move two days before Polk's inauguration, Tyler extended to Texas a formal offer of annexation.[44] Polk's first major decision in office was whether to recall Tyler's emissary to Texas, who bore an offer of annexation based on that act of Congress.[45] Though it was within Polk's power to recall the messenger, he chose to allow the emissary to continue, with the hope that Texas would accept the offer.[45] Polk also retained the United States Ambassador to Texas, Andrew Jackson Donelson, who sought to convince the Texan leaders to accept annexation under the terms proposed by the Tyler administration.[46] Though public sentiment in Texas favored annexation, some Texas leaders disliked the strict terms for annexation, which offered little leeway for negotiation and gave public lands to the federal government.[47] Nonetheless, in July 1845, a convention in Austin, Texas ratified the annexation of Texas.[48] In December 1845, Polk signed a resolution annexing Texas, and Texas became the 28th state in the union.[49] The annexation of Texas would lead to increased tensions with Mexico, which had never recognized Texan independence.[50]

Partition of Oregon Country[edit]

Background[edit]

Since the signing of the Treaty of 1818, the largely unsettled Oregon Country had been under the joint occupation and control of Great Britain and the United States. Previous U.S. administrations had offered to divide the region along the 49th parallel, which was not acceptable to Britain, as it had commercial interests along the Columbia River.[51] Britain's preferred partition, which would have awarded Puget Sound and all lands north of the Columbia River to Britain, was unacceptable to Polk.[51] Edward Everett, President Tyler's minister to Britain, had informally proposed dividing the territory at the 49th parallel with the strategic Vancouver Island granted to the British. However, when the new British minister Richard Pakenham arrived in Washington in 1844, he found that many Americans desired the entire territory.[52] Oregon had not been a major issue in the 1844 election, but the recent heavy influx of settlers to the Oregon Country and the rising spirit of expansionism in the United States made a treaty with Britain more urgent.[53]

Partition[edit]

Though both the British and the Americans sought an acceptable compromise regarding Oregon Country, each also saw the territory as an important geopolitical asset that would play a large part in determining the dominant power in North America.[51] In his inaugural address, Polk announced that he viewed the American claim to the land as "clear and unquestionable", provoking threats of war from British leaders should Polk attempt to take control of the entire territory.[54] Polk had refrained in his address from asserting a claim to the entire territory, which extended north to 54 degrees, 40 minutes north latitude, although the Democratic Party platform called for such a claim.[55] Despite Polk's hawkish rhetoric, he viewed war with the British as unwise, and Polk and Buchanan opened up negotiations with the British.[56] Like his predecessors, Polk again proposed a division along the 49th parallel, which was immediately rejected by Pakenham.[57] Secretary of State Buchanan was wary of a two-front war with Mexico and Britain, but Polk was willing to risk war with both countries in pursuit of a favorable settlement.[58]

In his December 1845 annual message to Congress, Polk requested approval of giving Britain a one-year notice (as required in the Treaty of 1818) of his intention to terminate the joint occupancy of Oregon.[59] In that message, he quoted from the Monroe Doctrine to denote America's intention of keeping European powers out, the first significant use of it since its origin in 1823.[60] After much debate, Congress eventually passed the resolution in April 1846, attaching its hope that the dispute would be settled amicably.[61] When the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Aberdeen, learned of the proposal rejected by Pakenham, Aberdeen asked the United States to re-open negotiations, but Polk was unwilling to do so unless a proposal was made by the British.[62]

With Britain moving towards free trade with the repeal of the Corn Laws, good trade relations with the United States were more important to Aberdeen than a distant territory.[63] In February 1846, Polk allowed Buchanan to inform Louis McLane, the American ambassador to Britain, that Polk's administration would look favorably on a British proposal based around a division at the 49th parallel.[64] In June 1846, Pakenham presented an offer to the Polk administration, calling for a boundary line at the 49th parallel, with the exception that Britain would retain all of Vancouver Island, and British subjects would be granted limited navigation rights on the Columbia River until 1859.[65] Polk and most of his cabinet were prepared to accept the proposal, but Buchanan, in a reversal, urged that the United States seek control of all of the Oregon Territory.[66]

After winning the reluctant approval of Buchanan,[67] Polk submitted the full treaty to the Senate for ratification. The Senate ratified the Oregon Treaty in a 41–14 vote, with opposition coming from those who sought the full territory.[68] Polk's willingness to risk war with Britain had frightened many, but his tough negotiation tactics may have gained the United States concessions from the British (particularly regarding the Columbia River) that a more conciliatory president might not have won.[69]

Mexican–American War[edit]

Background[edit]

The United States had been the first country to recognize Mexico's independence following the Mexican War of Independence, but relations between the two countries began to sour in the 1830s.[70] In the 1830s and 1840s, the United States, like France and Britain, sought a reparations treaty with Mexico for various acts committed by Mexican citizens and authorities, including the seizure of American ships.[70] Though the United States and Mexico had agreed to a joint board to settle the various claims prior to Polk's presidency, many Americans accused the Mexican government of acting in bad faith in settling the claims.[70] For its part, Mexico believed that the United States sought to acquire Mexican territory, and believed that many Americans filed specious or exaggerated claims.[70] The already-troubled Mexico–United States relations were further inflamed by the possibility of the annexation of Texas, as Mexico still viewed Texas as an integral part of their republic.[71] Additionally, Texas laid claim to all land north of the Rio Grande River, while Mexico argued that the more northern Nueces River was the proper Texan border.[72] Though the United States had a population more than twice as numerous and an economy thirteen times greater than that of Mexico, Mexico was not prepared to give up its claim to Texas, even if it meant war.[73]

The Mexican province of Alta California enjoyed a large degree of autonomy, and the central government neglected its defenses; a report from a French diplomat stated that "whatever nation chooses to send there a man-of-war and 200 men" could conquer California.[74] Polk placed great value in the acquisition of California, which represented new lands to settle as well as a potential gateway to trade in Asia.[75] He feared that the British or another European power would eventually establish control over California if it remained in Mexican hands.[76] In late 1845, Polk sent diplomat John Slidell to Mexico to win Mexico's acceptance of the Rio Grande border. Slidell was further authorized to purchase California for $20 million and New Mexico for $5 million.[77] Polk also sent Lieutenant Archibald H. Gillespie to California with orders to foment a pro-American rebellion that could be used to justify annexation of the territory.[78]

Outbreak of war[edit]

Following the Texan ratification of annexation in 1845, both Mexicans and Americans saw war as a likely possibility.[71] Polk began preparations for a potential war, sending an army led by General Zachary Taylor into Texas.[79] Taylor and Commodore David Conner of the U.S. Navy were both ordered to avoid provoking a war, but were authorized to respond to any Mexican breach of peace.[79] Though Mexican President José Joaquín de Herrera was open to negotiations, Slidell's ambassadorial credentials were refused by a Mexican council of government.[80] In December 1845, Herrera's government collapsed largely due to his willingness to negotiate with the United States; the possibility of the sale of large portions of Mexico aroused anger among both Mexican elites and the broader populace.[81]

As successful negotiations with the unstable Mexican government appeared unlikely, Secretary of War Marcy ordered General Taylor to advance to the Rio Grande River.[81] Polk began preparations to support a potential new government led by the exiled Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna with the hope that Santa Anna would sell parts of California.[82] Polk had been advised by Alejandro Atocha, an associate of Santa Anna, that only the threat of war would allow the Mexican government the leeway to sell parts of Mexico.[82] In March 1846, Slidell finally left Mexico after the government refused his demand to be formally received.[83] Slidell returned to Washington in May 1846, and gave his opinion that negotiations with the Mexican government were unlikely to be successful.[84] Polk regarded the treatment of his diplomat as an insult and an "ample cause of war", and he prepared to ask Congress for a declaration of war.[85]

Meanwhile, in late March 1846, General Taylor reached the Rio Grande, and his army camped across the river from Matamoros, Tamaulipas.[82] In April, after Mexican general Pedro de Ampudia demanded that Taylor return to the Nueces River, Taylor began a blockade of Matamoros.[84] A skirmish on the northern side of the Rio Grande ended in the death or capture of dozens of American soldiers, and became known as the Thornton Affair.[84] While the administration was in the process of asking for a declaration of war, Polk received word of the outbreak of hostilities on the Rio Grande.[84] In a message to Congress, Polk explained his decision to send Taylor to the Rio Grande, and stated that Mexico had invaded American territory by crossing the river.[86] Polk contended that a state of war already existed, and he asked Congress to grant him the power to bring the war to a close.[86] Polk's message was crafted to present the war as a just and necessary defense of the country against a neighbor that had long troubled the United States.[87] In his message, Polk noted that Slidell had gone to Mexico to negotiate a recognition of the Texas annexation, but did not mention that he also sought the purchase of California.[87]

Some Whigs, such as Abraham Lincoln, challenged Polk's version of events.[88] One Whig congressman declared "the river Nueces is the true western boundary of Texas. It is our own president who began this war. He has been carrying it on for months."[89] Nonetheless, the House overwhelmingly approved of a resolution authorizing the president to call up fifty thousand volunteers.[90] In the Senate, war opponents led by Calhoun also questioned Polk's version of events, but the House resolution passed the Senate in a 40–2 vote, marking the beginning of the Mexican–American War.[91] Many congressmen who were skeptical about the wisdom of going to war with Mexico feared that publicly opposing the war would cost them politically.[86][92]

Early war[edit]

Disputed territory United States territory, 1848 | Mexican territory retained after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Mexican territory lost in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo |

In May 1846, Taylor led U.S. forces in the inconclusive Battle of Palo Alto, the first major battle of the war.[93] The next day, Taylor led the army to victory in the Battle of Resaca de la Palma, eliminating the possibility of a Mexican incursion into the United States.[93] Taylor's force moved south towards Monterrey, which served as the capital of the province of Nuevo León.[94] In the September 1846 Battle of Monterrey, Taylor defeated a Mexican force led by Ampudia, but allowed Ampudia's forces to withdraw, much to Polk's consternation.[95]

Meanwhile, Winfield Scott, the army's lone major general at the outbreak of the war, was offered the position of top commander in the war.[96] Polk, War Secretary Marcy, and Scott agreed on a strategy in which the US would capture northern Mexico and then pursue a favorable peace settlement.[96] However, Polk and Scott experienced mutual distrust from the beginning of their relationship, in part due to Scott's Whig affiliation and former rivalry with Andrew Jackson.[97] Additionally, Polk sought to ensure that both Whigs and Democrats would serve in important positions in the war, and was offended when Scott suggested otherwise; Scott also angered Polk by opposing Polk's effort to increase the number of generals.[98] Having been alienated from Scott, Polk ordered Scott to remain in Washington, leaving Taylor in command of Mexican operations.[93] Polk also ordered Commodore Conner to allow Santa Anna to return to Mexico from his exile, and sent an army expedition led by Stephen W. Kearny towards Santa Fe.[99]

While Taylor fought the Mexican army in east, U.S. forces took control of California and New Mexico.[100] Army Captain John C. Frémont led settlers in Northern California in an attack on the Mexican garrison in Sonoma, beginning the Bear Flag Revolt.[101] In August 1846, American forces under Kearny captured Santa Fe, capital of the province of New Mexico.[102] He captured Santa Fe without firing a shot, as the Mexican Governor, Manuel Armijo, fled from the province.[103] After establishing a provisional government in New Mexico, Kearny took a force west to aid in the conquest of California. After Kearny's departure, Mexicans and Puebloans rebelled against the provisional government in the Taos Revolt, but U.S. forces crushed the uprising.[104] At roughly the same time that Kearny captured Santa Fe, Commodore Robert F. Stockton landed in Los Angeles and proclaimed the capture of California.[102] Californios rose up in rebellion against U.S. occupation, but Stockton and Kearny suppressed the revolt with a victory in the Battle of La Mesa. After the battle, Kearny and Frémont became embroiled in a dispute over the establishment of a government in California.[105] The controversy between Frémont and Kearny led to a break between Polk and the powerful Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, who was the father-in-law of Frémont.[106]

Growing domestic resistance[edit]

Whig opposition to the war grew after 1845, while some Democrats lost their initial enthusiasm.[107] In August 1846, Polk asked Congress to appropriate $2 million in hopes of using that money as a down payment for the purchase of California in a treaty with Mexico.[108] Polk's request ignited opposition to the war, as Polk had never before made public his desire to annex parts of Mexico (aside from lands claimed by Texas).[108] A freshman Democratic Congressman, David Wilmot of Pennsylvania, offered an amendment known as the Wilmot Proviso that would ban slavery in any newly acquired lands.[109] The appropriations bill, including the Wilmot Proviso, passed the House with the support Northern Whigs and Northern Democrats, breaking the normal pattern of partisan division in congressional votes. Wilmot himself held anti-slavery views, but many pro-slavery Northern Democrats voted for the bill out of anger at Polk's perceived bias towards the South. The partition of Oregon, the debate over the tariff, and Van Buren's antagonism towards Polk all contributed to Northern anger. The appropriations bill, including the ban on slavery, was defeated in the Senate, but the Wilmot Proviso injected the slavery debate into national politics.[110]

Polk's Democrats would pay a price for the resistance to the war and the growing issue of slavery, as Democrats lost control of the House in the 1846 elections. However, in early 1847, Polk was successful in passing a bill raising further regiments, and he also finally won approval for the money he wanted to use for the purchase of California.[111]

Late war[edit]

Santa Anna returned to Mexico City in September 1846, declaring that he would fight against the Americans.[112] With the duplicity of Santa Anna now clear, and with the Mexicans declining his peace offers, Polk ordered an American landing in Veracruz, the most important Mexican port on the Gulf of Mexico.[112] As a march from Monterrey to Mexico City was implausible due to rough terrain,[113] Polk had decided that a force would land in Veracruz and then march on Mexico City.[114] Taylor was ordered to remain near Monterrey, while Polk reluctantly chose Winfield Scott to lead the attack on Veracruz.[115] Though Polk continued to distrust Scott, Marcy and the other cabinet members prevailed on Polk to select the army's most senior general for the command.[116]

In March 1847, Polk learned that Taylor had ignored orders and had continued to march south, capturing the northern Mexican town of Saltillo.[117] Taylor's army had repulsed a larger Mexican force, led by Santa Anna, in the February 1847 Battle of Buena Vista.[117] Taylor won acclaim for the result of the battle, but the theater remained inconclusive.[117] Rather than pursuing Santa Anna's forces, Taylor withdrew back to Monterrey.[118] Meanwhile, Scott landed in Veracruz and quickly won control of the city.[119] Following the capture of Veracruz, Polk dispatched Nicholas Trist, Buchanan's chief clerk, to negotiate a peace treaty with Mexican leaders.[119] Trist was ordered to seek the cession of Alta California, New Mexico, and Baja California, recognition of the Rio Grande as the southern border of Texas, and American access across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.[120]

In April 1847, Scott defeated a Mexican force led by Santa Anna at the Battle of Cerro Gordo, clearing the way for a march on Mexico City.[121] In August, Scott defeated Santa Anna again at the Battle of Contreras and the Battle of Churubusco.[122] With these victories over a larger force, Scott's army was positioned to besiege Mexico's capital.[122] Santa Anna negotiated a truce with Scott, and the Mexican foreign minister notified Trist that they were ready to begin negotiations to end the war.[123] However, the Mexican and American delegations remained far apart on terms; Mexico was only willing to yield portions of Alta California, and still refused to agree to the Rio Grande border.[124] While negotiations continued, Scott captured the Mexican capital in the Battle for Mexico City.[125]

In the United States, a heated political debate emerged regarding how much of Mexico the United States should seek to annex, with Whigs such as Henry Clay arguing that the United States should only seek to settle the Texas border question, and some expansionists arguing for the annexation of all of Mexico.[126] Frustrated by the lack of progress in negotiations, and troubled by rumors that Trist was willing to negotiate on the Rio Grande border, Polk ordered Trist to return to Washington.[127] Polk decided to occupy large portions of Mexico and wait for a Mexican peace offer.[128] In late 1847, Polk learned that Scott had court-martialed a close ally of Polk's, Gideon Johnson Pillow.[129] Outraged by that event, Polk demanded Scott's return to Washington, with William Orlando Butler tapped as his replacement.[129]

Peace: the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo[edit]

In September 1847, Manuel de la Peña y Peña replaced Santa Anna as President of Mexico, and Pena and his Moderado allies showed a willingness to negotiate based on the terms Polk had relayed to Trist.[130] In November 1847, Trist received Polk's order to return to Washington.[130] After a period of indecision, and with the backing of Scott and the Mexican government (which was aware that Polk had ordered Trist's recall), Trist decided to enter into negotiations with the Mexican government.[130] As Polk had made no plans to send an envoy to replace him, Trist thought that he could not pass up the opportunity to end the war on favorable terms.[130] Though Polk was outraged by Trist's decision, he decided to allow Trist some time to negotiate a treaty.[131]

Throughout January 1848, Trist regularly met with Mexican officials in Guadalupe Hidalgo, a small town north of Mexico City.[132] Trist was willing to allow Mexico to keep Lower California, but successfully haggled for the inclusion of the important harbor of San Diego in a cession of Upper California.[132] The Mexican delegation agreed to recognize the Rio Grande border, while Trist agreed to have the United States cover prior American claims against the Mexican government.[132] The two sides also agreed to the right of Mexicans in annexed territory to leave or become U.S. citizens, American responsibility to prevent cross-border Indian raids, protection of church property, and a $15 million payment to Mexico.[132] On February 2, 1848, Trist and the Mexican delegation signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.[132]

Polk received the document on February 19,[133][134] and, after the Cabinet met on the 20th, decided he had no choice but to accept it. If he turned it down, with the House by then controlled by the Whigs, there was no assurance Congress would vote funding to continue the war. Both Buchanan and Walker dissented, wanting more land from Mexico.[135] Some senators opposed the treaty because they wanted to take no Mexican territory; others hesitated because of the irregular nature of Trist's negotiations. Polk waited in suspense for two weeks as the Senate considered it, sometimes hearing that it would likely be defeated, and that Buchanan and Walker were working against it. On March 10, the Senate ratified the treaty in a 38–14 vote that cut across partisan and geographic lines.[136] The Senate made some modifications to treaty, and Polk worried that the Mexican government would reject the new terms. Despite those fears, on June 7, Polk learned that Mexico had ratified the treaty.[137] Polk declared the treaty in effect as of July 4, 1848, thus ending the war.[138]

The Mexican Cession added 600,000 square miles of territory to the United States, including a long Pacific coastline.[137] The treaty also recognized the annexation of Texas and acknowledged American control over the disputed territory between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. Mexico, in turn, received $15 million.[132] The war had cost the lives of nearly 14,000 Americans and 25,000 Mexicans, and had cost the United States roughly one hundred million dollars.[137][139] With the exception of the territory acquired by the 1853 Gadsden Purchase, the territorial acquisitions under Polk established the modern borders of the Contiguous United States.[138]

Governing the new territories[edit]

Polk had been anxious to establish a territorial government for Oregon once the treaty was effective in 1846, but the matter became embroiled in the arguments over slavery, though few thought Oregon suitable for that institution. A bill to establish an Oregon territorial government passed the House after being amended to bar slavery; the bill died in the Senate when opponents ran out the clock on the congressional session. A resurrected bill, still barring slavery, again passed the House in January 1847, but it was not considered by the Senate before Congress adjourned in March. By the time Congress met again in December, California and New Mexico were in U.S. hands, and Polk in his annual message urged the establishment of territorial governments in California, New Mexico, and Oregon.[140] The Missouri Compromise had settled the issue of the geographic reach of slavery within the Louisiana Purchase territories by prohibiting slavery in states north of 36°30′ latitude. Polk sought to extend this line into the newly acquired territory.[141] If extended to the Pacific, this would have made slavery illegal in Northern California, but would have allowed it in Southern California.[142] A plan to accomplish the extension was defeated in the House by a bipartisan alliance of Northerners.[143] As the last congressional session before the 1848 election came to a close, Polk signed the lone territorial bill passed by Congress, which established the Territory of Oregon and prohibited slavery in it.[144]

When Congress reconvened in December 1848, Polk again called for the establishment territorial governments in California and New Mexico, a task made especially urgent by the onset of the California Gold Rush.[145] However, the divisive issue of slavery blocked any such legislation. Polk made it clear that he would veto a territorial bill that would have had the laws Mexico apply to the southwest territories until Congress, considering it to be the Wilmot Proviso in another guise. It was not until the Compromise of 1850 that the matter of the territories was resolved.[146]

Other initiatives[edit]

Panama[edit]

Polk's ambassador to the Republic of New Granada, Benjamin Alden Bidlack, negotiated the Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty with the government of New Granada in 1846.[147] Though Bidlack had initially only sought to remove tariffs on American goods, Bidlack and New Granadan Foreign Minister Manuel María Mallarino negotiated a broader agreement that deepened military and trade ties between the two countries.[147] The treaty also allowed for the construction of the Panama Railway.[148] In an era of slow overland travel, the treaty gave the United States a route to more rapidly travel between its eastern and western coasts.[148] In exchange, Bidlack agreed to have the United States guarantee New Granada's sovereignty over the Isthmus of Panama.[147] The treaty won ratification in both countries in 1848.[148] The agreement helped to establish a stronger American influence in the region, as the Polk administration sought to ensure that Great Britain would not dominate Central America.[148] The United States would use the Mallarino-Bidlack Treaty as justification for numerous military interventions in Panama.[147]

Cuba[edit]

In mid-1848, President Polk authorized his ambassador to Spain, Romulus Mitchell Saunders, to negotiate the purchase of Cuba and offer Spain up to $100 million, an astounding sum at the time for one territory, equal to $3.52 billion in present-day terms.[149] Cuba was close to the United States and had slavery, so the idea appealed to Southerners but was unwelcome in the North. However, Spain was still making huge profits in Cuba (notably in sugar, molasses, rum, and tobacco), and thus the Spanish government rejected Saunders' overtures.[150] Though Polk was eager to acquire Cuba, he refused to support the proposed filibuster expedition of Narciso López, who sought to invade and annex Cuba.[151]

Domestic affairs[edit]

Tariff reduction[edit]

The Tariff of 1842 had set relatively high tariff rates, and Polk made a reduction of tariff rates the top priority of his domestic agenda.[152] Though he had taken an ambivalent position on the tariff during the 1844 campaign in order to win Northern votes, Polk had long opposed a high tariff.[153] Many Americans, especially in the North, favored high tariffs as a means of protecting domestic manufacturing from foreign competition. Polk believed that protective tariffs were unfair to other economic activities, and he favored reducing tariff rates to the minimum level necessary for funding the federal government.[152] Upon taking office, Polk directed Secretary of the Treasury Walker to draft a law that would lower tariff rates.[153] Though foreign policy and other issues prevented Congress and the administration from focusing on tariff reduction in 1845 and early 1846, Walker worked with Congressman James Iver McKay to develop a tariff reduction bill. In April 1846, McKay reported the bill out of the House Ways and Means Committee for consideration by the full House of Representatives.[154]

After intense lobbying by both sides, the bill passed the House on July 3, with the vast majority of favorable votes coming from Democrats.[155] Consideration then moved to the Senate, and Polk intensely lobbied a group of wavering senators to assure passage of the bill.[156] In a close vote that required Vice President Dallas to break a tie, the Senate approved the tariff bill in July 1846.[157] Dallas, from protectionist Pennsylvania, voted for the bill because he decided that his best political prospects lay in supporting the administration.[158] Following the congressional passage of the bill, Polk signed the Walker Tariff into law, substantially reducing the rates that had been set by the Tariff of 1842.[154] The Walker Tariff would remain in place until the passage of the Tariff of 1857, staying in effect longer than any other tariff measure of the nineteenth century.[159] The reduction of tariffs in the United States and the repeal of the Corn Laws in Great Britain led to a boom in Anglo-American trade[160] and, in large part due to growing international trade, the economy entered a strong period of growth in the late 1840s.[161]

Banking policy[edit]

In his inaugural address, Polk called upon Congress to re-establish the Independent Treasury System under which government funds were held in the Treasury and not in banks or other financial institutions.[162] Under that system, the government would store federal funds in vaults in the Treasury Building and other government buildings, where those funds would remain until they were used to fund the government.[163] President Van Buren had previously established the Independent Treasury system, but it had been abolished during the Tyler administration.[164] Under the status quo that prevailed when Polk took office, the government deposited its funds in state banks, which could then use those funds in ordinary banking operations. Polk believed that this policy resulted in inflation, and was also philosophically opposed to involving the government in banking.[165] The Whigs had wanted to create a new national bank since the expiration of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States in 1836, but their efforts had been vetoed by President Tyler, and Polk strongly opposed the re-establishment of a national bank.[165] In a party-line vote, the House of Representatives approved Polk's Independent Treasury bill in April 1846.[163] After personally winning the support of Senator Dixon Lewis, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Polk was able to push the Independent Treasury Act through the Senate, and he signed the act into law on August 6, 1846. The system would remain in place until the passage of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913.[160]

Opposition to internal improvements bills[edit]

During Polk's presidency, Congress passed bills to provide federal funding for internal improvements such as roads, canals, and harbors. Those who favored such funding, many of whom were Whigs, believed that internal improvements aided economic development and Western settlement. Unlike tariffs and monetary policy, support for federally-funded internal improvements split the Democratic Party, and a coalition of Democrats and Whigs arranged for the passage of internal improvement bills despite Polk's opposition.[166] Polk considered internal improvements to be matters for the states, and feared that the passage of federal internal improvements bill would encourage legislators to compete for favors for their home district; Polk felt that such competition for federal resources damaged the virtue of the republic. When Congress passed the Rivers and Harbors Bill in 1846 to provide $500,000 to improve port facilities, Polk vetoed it. Polk believed that the bill was unconstitutional because it unfairly favored particular areas, including ports that had no foreign trade.[167] In this regard he followed his hero Jackson, who had vetoed the Maysville Road Bill in 1830 on similar grounds.[168] In 1847, Polk pocket vetoed another internal improvements bill, and Congress would not pass a similar bill during his presidency.[169]

Other domestic issues[edit]

Slavery[edit]

Like Jackson, Polk saw slavery as a side issue compared to other matters such as territorial expansion and economic policy.[170] However, the issue of slavery became increasingly polarizing during the 1840s, and Polk's expansionary policies increased its divisiveness.[170] During his presidency, many abolitionists harshly criticized him as an instrument of the "Slave Power", and claimed that he supported western expansion because he wanted to extend slavery into new territories.[171] For his part, Polk accused both northern and southern leaders of attempting to use the slavery issue for political gain.[172] The divisive debate over slavery in the territories led to the creation of the Free Soil Party, an anti-slavery (though not abolitionist) party that attracted Democrats, Whigs, and members of the Liberty Party.[173]

California Gold Rush and the Coinage Act of 1849[edit]

Authoritative word of the discovery of gold in California did not arrive in Washington until after the 1848 election, by which time Polk was a lame duck. Polk was delighted by the discovery of gold, seeing it as validation of his stance on expansion, and he referred to the discovery several times in his final annual message to Congress that December. Shortly thereafter, actual samples of the California gold arrived, and Polk sent a special message to Congress on the subject. The message, confirming less authoritative reports, caused large numbers of people to move to California, both from the U.S. and abroad, thus helping to spark the California Gold Rush.[174] The California gold rush injected large quantities of gold into the U.S. economy, helping to ease a long-term shortage of gold coins. In large because of this gold, the Whigs were unable to whip up popular enthusiasm for a revival of the national bank after Polk left office.[175]

In response to the Gold Rush, the House introduced the Coinage Act of 1849 which allowed for the minting of two new denominations of gold coins, the gold dollar and the gold $20 or double eagle. It further defined the variances which were permissible in United States gold coinage. The act was approved on March 3, 1849, and Polk signed it on that same day, marking one of his final acts as president. The act contains four sections.

Department of the Interior[edit]

One of Polk's last acts as president was to sign the bill creating the Department of the Interior (March 3, 1849). This was the first new cabinet position created since the early days of the Republic. Polk had misgivings about the federal government usurping power over public lands from the states. Nevertheless, the delivery of the legislation on his last full day in office gave him no time to find constitutional grounds for a veto, or to draft a sufficient veto message, so he signed the bill.[176]

States admitted to the Union[edit]

Three states were admitted to the Union during Polk's presidency:

1848 election[edit]

Honoring his pledge to serve only one term, Polk declined to seek re-election in 1848. With Polk out of the race, the Democratic Party remained fractured along geographic lines.[177] Polk privately favored Lewis Cass as his successor, but resisted becoming closely involved in the election.[178] At the 1848 Democratic National Convention, Buchanan, Cass, and Supreme Court Justice Levi Woodbury emerged as the main contenders.[179] Cass drew support from both the North and South with his doctrine of popular sovereignty, under which each territory would decide the legal status of slavery.[180] Cass led after the first ballot, and slowly gained support until he clinched the nomination on the fourth ballot.[179] William Butler, who had replaced Winfield Scott as the commanding general in Mexico City, won the vice presidential nomination.[179] Cass's nomination alienated many northerners and southerners, each of whom saw Cass as insufficiently committed to their position on the slavery issue.[179]

During the course of the Mexican War, Generals Taylor and Scott emerged as strong Whig candidates.[181] As the war continued, Taylor's stature with the public grew, and he announced in 1847 that he would not refuse the presidency.[181] The 1848 Whig National Convention took place on June 8, with Taylor, Scott, Henry Clay, and Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster emerging as the major candidates.[182] Taylor narrowly led Clay after the first ballot, and his support steadily grew until he captured the nomination on the fourth ballot.[182] Clay bemoaned the selection of the ideologically ambiguous Taylor, who had not articulated his preferred policies on the major issues of the day.[182] The Whigs chose former Congressman Millard Fillmore of New York as Taylor's running mate.[182]

In New York, an anti-slavery Democratic faction known as the Barnburners strongly supported the Wilmot Proviso and rejected Cass.[183] Joined by other anti-slavery Democrats from other states, the Barnburners held a convention nominating former President Martin Van Buren as their own presidential nominee, and Van Buren eventually became the Free Soil Party's nominee.[183] Though Van Buren had not been known for his anti-slavery views while president, he embraced them in 1848.[183] Van Buren's decision to run was also affected by Polk's decision to give patronage to rival factions in New York.[184] Polk was surprised and disappointed by his former ally's political conversion, and he worried about the divisiveness of a sectional party organized around anti-slavery principles.[183] Van Buren was joined on the Free Soil Party's ticket by Charles Francis Adams Sr., son of former president and prominent Whig John Quincy Adams.[185]

In the election, Taylor won 47.3% of the popular vote and a majority of the electoral vote, giving the Whigs control of the presidency. Cass won 42.5% of the vote, while Van Buren finished with 10.1% of the popular vote, more than any other third-party presidential candidate at that time. Despite the increasingly polarizing slavery debate, Taylor and Cass both won a mix of northern and southern states, while most of Van Buren's support came from northern Democrats.[186] Polk was very disappointed by the outcome as he had a low opinion of Taylor, seeing the general as someone with poor judgment and few opinions.[186] Polk left office in March 1849, and he died the following June.[187]

Historical reputation[edit]

Polk's historic reputation was largely formed by the attacks made on him in his own time. Whig politicians claimed that he was drawn from a well-deserved obscurity. Sam Houston is said to have observed that Polk was "a victim of the use of water as a beverage".[188] Senator Tom Corwin of Ohio remarked "James K. Polk, of Tennessee? After that, who is safe?" The Republican historians of the nineteenth century inherited this view. Polk was a compromise between the Democrats of the North, like David Wilmot and Silas Wright, and Southern plantation owners led by John C. Calhoun. The Northern Democrats thought that when they did not get their way, it was because he was the tool of the slaveholders, and the conservatives of the South insisted that he was the tool of the Northern Democrats. These views were long reflected in the historical literature, until Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and Bernard De Voto argued that Polk was nobody's tool, but set his own goals and achieved them.[189]

Polls of historians and political scientists have generally ranked Polk as an above-average president, and Polk tends to rank higher than every other president who served between the presidencies of Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln. A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Polk as the 21st best president.[190] A 2017 C-SPAN poll of historians ranked Polk as the 14th best president.[191]

Polk biographers over the years have sized up the magnitude of Polk's achievements and his legacy, particularly his two most recent. "There are three key reasons why James K. Polk deserves recognition as a significant and influential American president," Walter Borneman wrote. "First, Polk accomplished the objectives of his presidential term as he defined them; second, he was the most decisive chief executive before the Civil War; and third, he greatly expanded the executive power of the presidency, particularly its war powers, its role as commander-in-chief, and its oversight of the executive branch."[192] Political scientist Leonard White summed up Polk's command system:

- He determined the general strategy of military and naval operations; he chose commanding officers; he gave personal attention to supply problems; he energized so far as he could the General Staff; he controlled the military and naval estimates; and he used the cabinet as a major coordinating agency for the conduct of the campaign.[193]

While Polk's legacy thus takes many forms, the most outstanding is the map of the continental United States, whose landmass he increased by a third. "To look at that map," Robert Merry concluded, "and to take in the western and southwestern expanse included in it, is to see the magnitude of Polk's presidential accomplishments."[194] Though there were powerful forces compelling Americans to the Pacific Ocean, some historians, such as Gary Kornblith, have posited that a Clay presidency would have seen the permanent independence of Texas and California.[195]

Nevertheless, Polk's aggressive expansionism has been criticized on ethical grounds. He believed in "Manifest Destiny" even more than most did. Referencing the Mexican–American War, ex-president Ulysses S. Grant stated that "I was bitterly opposed to the [Texas annexation], and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory."[196] Whig politicians, including Abraham Lincoln and John Quincy Adams, contended that the Texas Annexation and the Mexican Cession enhanced the pro-slavery factions of the United States.[197] Unsatisfactory conditions pertaining to the status of slavery in the territories acquired during the Polk administration led to the Compromise of 1850, one of the primary factors in the establishment of the Republican Party and later the beginning of the American Civil War.[198]

References[edit]

- ^ The Overlooked President from TheDailyBeast.com

- ^ Merry p. 43-44

- ^ Merry p. 50-53

- ^ Merry p. 75

- ^ Merry p. 68-69

- ^ Merry p. 80

- ^ Merry, pg. 84–85

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 87–88

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 92–94

- ^ a b "James K. Polk: Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- ^ Merry, pg. 94–95

- ^ Merry, pp. 103–104

- ^ Haynes, pp. 61–62

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 99–100

- ^ "Presidential Elections". history.com. A+E Networks. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ Merry, pg. 96–97

- ^ Howe, pp. 684–685.

- ^ Howe, p. 686.

- ^ Wilentz, Sean (2008). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. W.W. Horton and Company. p. 574.

- ^ Howe, p. 688.

- ^ "The 15th Presidential Inauguration: James K. Polk, March 4, 1845". Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ Byrnes, Mark E. (2001). James K. Polk: A Biographical Companion. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 101–102. ISBN 1-57607-056-5. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ^ "Inaugural Address of James Knox Polk". Avalon Project. New Haven, Connecticut: Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 132–133

- ^ a b c Merry, pg. 131–132

- ^ Merry, pg. 134–135

- ^ Merry, pg. 269–270

- ^ Merry, pg. 114–117

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 104–106

- ^ Merry, pg. 134, 220–221

- ^ Merry, pg. 439–440

- ^ a b c d e Merry, pg. 117–119

- ^ a b c Merry, pg. 124–126

- ^ Merry, pg. 127

- ^ Merry, pg. 282

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 163–164

- ^ Merry, pp. 220–221

- ^ Bergeron, pp.164–166

- ^ "Levi Woodbury". Oyez. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ "Robert C. Grier". Oyez. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ "Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, 1789–present". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved December 22, 2017. Searches run from page by choosing "select research categories" then check "court type" and "nominating president", then select type of court and James K. Polk.

- ^ McPherson, pg. 47

- ^ a b c Merry, pg. 120–124

- ^ Merry, pg. 127–128

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 136–137

- ^ Merry, pg. 148–151

- ^ Merry, pg. 151–157

- ^ Merry, pg. 158

- ^ Merry, pp. 211–212

- ^ Borneman, pp. 190–192

- ^ a b c Merry, pp. 168–169

- ^ Leonard, p. 95

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 115–116

- ^ Merry, pp. 170–171

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 116–118

- ^ Merry, pp. 173–175

- ^ Merry, p. 190

- ^ Merry, pp. 190–191

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 122–123

- ^ Pletcher, p. 307

- ^ Leonard, p. 118

- ^ Merry, pp. 196–197

- ^ Leonard, p. 108

- ^ Bergeron, p. 128

- ^ Pletcher, pp. 407–410

- ^ Pletcher, pp. 411–412

- ^ Rawley, James A. (February 2000). "Polk, James K.". American National Biography Online. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0400795.

- ^ Bergeron, p. 133

- ^ Merry, pp. 266–267

- ^ a b c d Merry, pg. 184–186

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 176–177

- ^ Merry, pg. 187

- ^ Merry, pg. 180

- ^ Howe, p. 709

- ^ Howe, pp. 735–736

- ^ Lee, Jr., Ronald C. (Summer 2002). "Justifying Empire: Pericles, Polk, and a Dilemma of Democratic Leadership". Polity. 34 (4): 526. doi:10.1086/POLv34n4ms3235415. JSTOR 3235415. S2CID 157742804.

- ^ Howe, p. 734

- ^ Merry, pg. 295–296

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 188–189

- ^ Merry, pg. 209–210

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 218–219

- ^ a b c Merry, pg. 238–240

- ^ Merry, pg. 232–233

- ^ a b c d Merry, pg. 240–242

- ^ Haynes, p. 129

- ^ a b c Merry, pg. 244–245

- ^ a b Lee, pgs. 517–518

- ^ Mark E. Neely, Jr., "War And Partisanship: What Lincoln Learned from James K. Polk," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Sept 1981, Vol. 74 Issue 3, pp 199–216

- ^ Howe, pp. 741–742

- ^ Merry, pg. 245–246

- ^ Merry, pg. 246–247

- ^ In January 1848, the Whigs won a House vote attacking Polk in an amendment to a resolution praising Major General Taylor for his service in a "war unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun by the President of the United States". House Journal, 30th Session (1848) pp.183–184 The resolution, however, died in committee.

- ^ a b c Merry, pg. 259–260

- ^ Howe, pp. 772–773

- ^ Merry, pg. 311–313

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 256–257

- ^ Merry, pg. 253–254

- ^ Merry, pg. 258–259

- ^ Merry, pg. 262

- ^ Howe, pp. 752–762

- ^ Merry, pg. 302–304

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 293–294

- ^ Merry, pg. 298–299

- ^ Howe, pp. 760–762

- ^ Howe, pp. 756–757

- ^ Merry, pg. 423–424

- ^ Howe, pp. 762–766

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 283–285

- ^ Merry, pg. 286–289

- ^ McPherson, pp. 53–54

- ^ Merry, pg. 343–349

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 309–310

- ^ Merry, pg. 314

- ^ Merry, pg. 336

- ^ Merry, pg. 318-20

- ^ Seigenthaler, pg. 139–140

- ^ a b c Merry, pg. 352–355

- ^ Howe, pp. 777–778

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 358–359

- ^ Merry, pg. 360–361

- ^ Merry, pg. 363–364

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 381–382

- ^ Merry, pg. 383–384

- ^ Merry, pg. 384–385

- ^ Merry, pg. 387–388

- ^ Merry, pg. 394–397

- ^ Merry, pg. 386

- ^ Merry, pg. 403–404

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 407–409

- ^ a b c d Merry, pg. 397–400

- ^ Merry, pg. 420–421

- ^ a b c d e f Merry, pg. 424–425

- ^ Borneman, pp. 308–309

- ^ Pletcher, p. 517

- ^ Greenberg, pp. 260–261

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 104–105

- ^ a b c Merry, pp. 448–450

- ^ a b Leonard, p. 180

- ^ Rough estimate of total cost, Smith, II 266–67; this includes the payments to Mexico in exchange for the ceded territories. The excess military appropriations during the war itself were $63,605,621.

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 202–205

- ^ Merry, pp. 452–453

- ^ Dusinberre, p. 143

- ^ Merry, pp. 458–459

- ^ Merry, pp. 460–461

- ^ Bergeron, p. 208

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 210–211

- ^ a b c d Conniff, Michael L. (2001). Panama and the United States: The Forced Alliance. University of Georgia Press. pp. 19–33. ISBN 9780820323480.

- ^ a b c d Randall, Stephen J. (1992). Colombia and the United States: Hegemony and Interdependence. University of Georgia Press. pp. 27–33. ISBN 9780820314020.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ David M. Pletcher, The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War (1973) pp. 571–74.

- ^ Chaffin, Tom (Spring 1995). ""Sons of Washington": Narciso López, Filibustering, and U.S. Nationalism, 1848–1851". Journal of the Early Republic. 15 (1). University of Pennsylvania Press: 79–108. doi:10.2307/3124384. JSTOR 3124384.

- ^ a b Bergeron, pp. 185–186

- ^ a b Seigenthaler, pp. 113–114

- ^ a b Bergeron, pp. 186–188

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 187–189

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 189–190

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 115–116

- ^ Pletcher, p. 419

- ^ Bergeron, p. 186

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 276–277

- ^ Howe, p. 829

- ^ Merry, pg. 206–207

- ^ a b Bergeron, p. 192

- ^ Seigenthaler, pp. 121–122

- ^ a b Bergeron, pp. 191–192

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 193–195

- ^ Yonatan Eyal, The Young America movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party (2007) p. 63

- ^ Mark Eaton Byrnes, James K. Polk: a biographical companion (2001) p. 44

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 196–200

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 129–130

- ^ Haynes, p. 154

- ^ Merry, pg. 356–358

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 206–207

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 319–321

- ^ Howe, pp. 815–816

- ^ Borneman, pp. 334–45

- ^ Merry, pg. 376–377

- ^ Merry, pp. 430–431

- ^ a b c d Merry, pg. 446–447

- ^ McPherson, p. 58

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 374–375

- ^ a b c d Merry, pg. 447–448

- ^ a b c d Merry, pg. 455–456

- ^ Howe, p. 832

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 252–253

- ^ a b Merry, pg. 462–463

- ^ Bergeron, pp. 256–260

- ^ Borneman, p. 11.

- ^ Schlesinger, pp.439–455; quote from Corwin (who became a Republican) on p. 439

- ^ Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin S. (19 February 2018). "How Does Trump Stack Up Against the Best — and Worst — Presidents?". New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ "Presidential Historians Survey 2017". C-SPAN. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ Borneman, p. 353.

- ^ White, Leonard D. The Jacksonians: A Study in Administrative History, 1829–1861 (1954) p. 54.

- ^ Merry, Robert W. (2009). A Country of Vast Designs, James K. Polk, the Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent. Simon & Schuster. p. 477.

- ^ Kornblith, Gary J. (June 2003). "Rethinking the Coming of the Civil War: A Counterfactual Exercise". The Journal of American History. 90 (1): 76–105. doi:10.2307/3659792. JSTOR 3659792.

- ^ Ulysses S Grant Quotes on the Military Academy and the Mexican War from Fadedgiant.net Archived March 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stephenson, Nathaniel Wright. Texas and the Mexican War: A Chronicle of Winning the Southwest. Yale University Press (1921), pg. 94–95.

- ^ Holt, Michael F. The Political Crisis of the 1850s (1978).

Works cited[edit]

- Bergeron, Paul H. (1986). The Presidency of James K. Polk. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press. ISBN 978-0-7006-0319-0.

- Borneman, Walter R. (2008). Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6560-8.

- Dusinberre, William (2003). Slavemaster President: The Double Career of James Polk. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515735-2.

- Greenberg, Amy S. (2012). A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-59269-9.

- Haynes, Sam W. (1997). James K. Polk and the Expansionist Impulse. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-673-99001-3.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: the Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Lee, Jr., Ronald C. (Summer 2002). "Justifying Empire: Pericles, Polk, and a Dilemma of Democratic Leadership". Polity. 34 (4): 503–531. doi:10.1086/POLv34n4ms3235415. JSTOR 3235415. S2CID 157742804.

- Leonard, Thomas M. (2000). James K. Polk: A Clear and Unquestionable Destiny. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources Inc. ISBN 978-0-8420-2647-5..

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7.

- Merry, Robert W. (2009). A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-9743-1.

- Pletcher, David M. (1973). The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri. ISBN 978-0-8262-0135-5.

- Seigenthaler, John (2004). James K. Polk. New York, New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6942-6.

- White, Leonard D. 1954. The Jacksonians: A Study in Administrative History, 1829-1861.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Manifest Destinies: America's Westward Expansion and the Road to the Civil War. New York, New York: Albert A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26524-1.

Further reading[edit]

- Campbell, Karlyn K. “James Knox Polk: The first imperial president?" in Before the Rhetorical Presidency, edited by Martin Medhurst, (Texas A&M University Press, 2008), pp. 83–102.

- Campbell, Karlyn K., & Kathleen Jamieson. Deeds Done in Words (University of Chicago Press, 1990).

- Chaffin, Tom. Met His Every Goal? James K. Polk and the Legends of Manifest Destiny (University of Tennessee Press; 2014) 124 pages.

- Dallas, George M. "James Knox Polk." in African Americans and the Presidents: Politics and Policies from Washington to Trump (2019): 38+ online.

- Devoti, John. "The patriotic business of seeking office: James K. Polk and the patronage" (PhD dissertation, Temple University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2005. 3203004).

- De Voto, Bernard. The Year of Decision: 1846. Houghton Mifflin, 1943.

- Eisenhower, John S. D. "The Election of James K. Polk, 1844". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 53.2 (1994): 74–87. ISSN 0040-3261; popular.

- Graff, Henry F., ed. The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed. 2002) online

- Greenstein, Fred I. "The policy-driven leadership of James K. Polk: making the most of a weak presidency." Presidential Studies Quarterly 40#4 (2010), p. 725+. online

- Heidt, Stephen J. “Presidential Power and National Violence: James K. Polk’s Rhetorical Transfer of Savagery.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 19#3 (2016), pp. 365–96, online.

- Kornblith, Gary J. "Rethinking the Coming of the Civil War: a Counterfactual Exercise". Journal of American History 90.1 (2003): 76–105. ISSN 0021-8723. Asks what if Polk had not gone to war?

- Leonard, Thomas. James K. Polk: A Clear and Unquestionable Destiny (Scholarly Resources Inc, 2001).

- McCormac, Eugene Irving. James K. Polk: A Political Biography to the End of a Career, 1845–1849. Univ. of California Press, 1922. (1995 reprint has ISBN 0-945707-10-X.) hostile to Jacksonians

- Merk, Frederick. Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History: A Reinterpretation (Vintage Books, 1966).

- Morrison, Michael A. "Martin Van Buren, the Democracy, and the Partisan Politics of Texas Annexation". Journal of Southern History 61.4 (1995): 695–724. ISSN 0022-4642. Discusses the election of 1844.

- Nau, Henry R. “James K. Polk: Manifest Destiny.” in Conservative Internationalism: Armed Diplomacy under Jefferson, Polk, Truman, and Reagan (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 110–46, online.

- Nelson, Anna Louise Kasten. "The Secret Diplomacy of James K. Polk during the Mexican War, 1846–1847" PhD dissertation, The George Washington University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1972. 7304017).

- Palmer‐Mehta, Valerie. "Sarah Polk: Ideas of Her Own." in A Companion to First Ladies (2016): 159–175.

- Paul; James C. N. Rift in the Democracy. (1951). on 1844 election

- Rayback, Joseph G. (2015). Free Soil: The Election of 1848. University of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813164434.

- Rowe, Christopher. "American society through the prism of the Walker Tariff of 1846." Economic Affairs 40.2 (2020): 180–197.

- Ruiz, Ramon, ed. The Mexican War: Was it Manifest Destiny? (1963) excerpts from primary and secondary sources.

- Schoenbeck, Henry Fred. "The economic views of James K. Polk as expressed in the course of his political career" (PhD dissertation, The University of Nebraska – Lincoln; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1951. DP13923).

- Sellers, Charles. James K. Polk, Jacksonian, 1795–1843 (1957) vol 1 online; and James K. Polk, Continentalist, 1843–1846. (1966) vol 2 online; long scholarly biography

- Silbey, Joel H. (2014). A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 1837–1861. Wiley. ISBN 9781118609293. pp 195–290

- Smith, Justin Harvey. The War with Mexico, Vol 1. (2 vol 1919), full text online.

- Smith, Justin Harvey. The War with Mexico, Vol. 2. (2 vol 1919). full text online; Pulitzer prize; still a major standard source,

- Weinberg, Albert. Manifest Destiny: A Study of Nationalist Expansionism in American History (1935) online

- Williams, Frank J. “James K. Polk.” in The Presidents and the Constitution: A Living History, edited by Ken Gormley, NYU Press, 2016, pp. 149–58, online.

- Winders, Richard Bruce. Mr. Polk's army: the American military experience in the Mexican war (Texas A&M University Press, 2001).

Historiography[edit]

- Notaro, Carmen. “Biography and James K. Polk: Observations on an Historiography Spanning Two Centuries.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 75#4 (2016), pp. 260–75, online.

Primary sources[edit]

- Cutler, Wayne, et al. Correspondence of James K. Polk. 1972–2004. ISBN 1-57233-304-9. Multivolume scholarly edition of the complete correspondence to and from Polk.

- Polk, James K. The Diary of James K. Polk During His Presidency, 1845–1849 edited by Milo Milton Quaife, 4 vols. 1910. Abridged version by Allan Nevins. 1929/

External links[edit]

- Works by or about Presidency of James K. Polk at Internet Archive

- James K. Polk: A Resource Guide, from the Library of Congress

- James K. Polk's Personal Correspondence Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Extensive essay on James K. Polk and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Inaugural Address of James K. Polk from The Avalon Project at the Yale Law School

- Biography of James K. Polk from the official White House website

- President James K. Polk State Historic Site, Pineville, North Carolina from a State of North Carolina website

- "Life Portrait of James K. Polk", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, May 28, 1999