Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger

| Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger | |

|---|---|

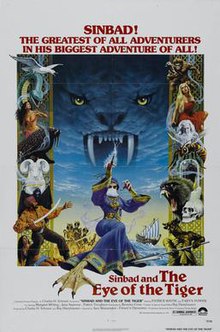

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sam Wanamaker |

| Written by | Beverley Cross |

| Based on | Sinbad the Sailor from One Thousand and One Nights |

| Produced by | Charles H. Schneer Ray Harryhausen |

| Starring | Patrick Wayne Taryn Power Margaret Whiting Jane Seymour Patrick Troughton |

| Cinematography | Ted Moore, B.S.C. |

| Edited by | Roy Watts |

| Music by | Roy Budd[1] |

Production company | Andor Films |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 113 min. |

| Countries | United States United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.5 million[3] or $3 million[4] |

| Box office | $20 million[4] |

Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger is a 1977 fantasy adventure film directed by Sam Wanamaker and featuring stop-motion effects by Ray Harryhausen. The film stars Patrick Wayne, Taryn Power, Jane Seymour and Patrick Troughton. The third and final Sinbad film released by Columbia Pictures, it follows The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973).

Plot

[edit]In the kingdom of Charak, a celebration is taking place for the coronation of Prince Kassim, but Kassim's evil stepmother, Zenobia, places a curse on him just as he is going to be crowned Caliph. Sinbad, a sailor and Prince of Baghdad, moors at Charak some time later, intent on seeking permission from Prince Kassim to marry Kassim's sister, Princess Farah, but finds the city under curfew. Sinbad and his men are offered hospitality by a man named Rafi, but during their meal one of Sinbad's crew is poisoned and the rest are attacked by Rafi, who is Zenobia's son. Sinbad defeats him, but Zenobia summons a trio of ghouls, which attack Sinbad and his men. Sinbad disposes of the ghouls by crushing them under a pile of huge logs.

Sinbad meets with Farah, who believes that Kassim's curse is one of Zenobia's spells, and unless Kassim is cured within seven moons, Zenobia's son Rafi will become caliph instead. Sinbad, Farah and Sinbad's crew set off to find the old Greek alchemist Melanthius, a hermit on the island of Casgar, who is said to know how to break curses, and Farah brings with her a huge prehistoric baboon, who is really Kassim, transformed by Zenobia's curse. Zenobia and Rafi follow in a boat propelled by the Minoton, a magical bronze automaton created by the sorceress with the appearance of a minotaur.

Sinbad and Farah land at Casgar and find Melanthius and his daughter Dione, who agree to help them. Melanthius says they must travel to the land of Hyperborea where the ancient civilization of the Arimaspi once existed. On the way to Hyperborea, Kassim enjoys having Dione's company and develops a love interest towards her.

Zenobia uses a potion to transform herself into a seagull to spy on Sinbad. Once aboard his ship, she turns into a miniature human and listens as Melanthius tells Sinbad how to cure Kassim. Alerted by Kassim, Melanthius and Sinbad capture Zenobia. However, her potion vial spills. Melanthius suspects the potion is what transformed Kassim, and experiments by feeding some to a wasp. The wasp grows to enormous size and attacks him and Sinbad, but Sinbad kills it. Zenobia uses her potion to once again become a seagull again and fly back to her own ship, but with not enough potion left to return to human form, the lower part of her right leg remains a seagull's foot.

After a long voyage, Sinbad's ship reaches the north polar wastelands. Sinbad and his crew trek across the ice to the land of the Arimaspi, but are attacked by a giant walrus. It destroys most of their supplies and kills two men, but Sinbad and the others fend it off with spears. Zenobia uses an ice tunnel to reach the land of the Arimaspi, and she, Rafi and the Minoton climb subterranean stairs to emerge in the warm, Mediterranean-like valley above.

Sinbad and his crew also reach the valley. While resting, they encounter a troglodyte, an 8-foot-tall (2.4 m), fur-covered caveman-like being with a single horn on the top of its head. The troglodyte proves not dangerous, but rather friendly. The adventurers name him Trog for short, and he leads them to the giant pyramidal shrine of the Arimaspi. Zenobia and Rafi arrive at the shrine first, but as she has no key to enter, Zenobia orders the Minoton to remove a block of stone from the pyramid's wall. He succeeds, but the block crushes the Minoton and destabilizes the pyramid's structure and thus the shrine's power.

Sinbad and his friends arrive minutes later and enter the shrine's main chamber, the interior of which is covered in ice and is protected by "The Guardian of the Shrine", a smilodon frozen in a block of ice. Zenobia orders Rafi to attack Melanthius and is about to stab Dione with a knife, but Rafi is attacked by Kassim and is killed falling down the temple stairs. Momentarily overcome with grief, Zenobia cradles her son while Sinbad and Melanthius raise Kassim into the column of light at the top of the shrine, which breaks the spell on him. Seeing Kassim restored to human form, Zenobia transfers her spirit into the smilodon. Breaking free of its icy prison, Zenobia attacks the group, but Trog engages Zenobia in combat wielding Minoton's spear. Initially gaining the upper hand, Trog is disarmed, overcome and killed. Sinbad and his men fight against the beast, but find themselves outmatched and Maroof is killed. Zenobia attacks Sinbad, who impales her on Minoton's spear, killing her. The adventurers flee the temple as it collapses, becoming buried in snow and ice as the Mediterranean-like atmosphere disappears and is replaced by the freezing polar winds.

Sinbad, Kassim, Farah, Melanthius and Dione return home just in time for Kassim to be crowned Caliph. Amidst the celebration, Sinbad and Farah kiss while the film fades to black and the eyes of Zenobia appear on the screen.

Cast

[edit]- Patrick Wayne as Sinbad

- Taryn Power as Dione

- Margaret Whiting as Zenobia

- Jane Seymour as Farah

- Patrick Troughton as Melanthius

- Kurt Christian as Rafi

- Nadim Sawalha as Hassan

- Damien Thomas as Kassim

- Bruno Barnabe as Balsora

- Bernard Kay as Zabid

- Salami Coker as Maroof

- Peter Mayhew as Minoton

- David Sterne as Aboo-Seer

Production

[edit]

The strong box office success of The Golden Voyage of Sinbad led Columbia Pictures executives to begin work on a third Sinbad motion picture with the second still in theatrical release. The plan was to move away from some of the legendary creatures which had been features of previous films and use more recognizable prehistoric animals.[5]

Schneer had worked with Sam Wanamaker on The Executioner and hired him for this because "I wanted an actor's director for Eye of the Tiger, to see if we could get more dimension out of other-wise cardboard characters. Sam didn't have to handle any of the technical aspects of the picture. He merely had to pay attention to them. Within the parameters of the technical work, he directed the dramatic sections. The technical work was carried out by Ray and me".[6]

Legendarily tall (7 ft 3 in [2.21 m]) performer Peter Mayhew made an unbilled acting debut in the film in some live-action sequences as the Minoton,[7][8] while Patrick Troughton (who had played the harpy-plagued blind Phineus in Harryhausen's 1963 film, Jason and the Argonauts) played Melanthius.[5] Kurt Christian, who played one of Sinbad's men in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, switched sides and played Zenobia's evil son Rafi.[9]

Patrick Wayne's casting was announced in May 1975, when Columbia said the director would be Sam Wanamaker.[10]

Schneer said: "I thought we would have some chemistry with John Wayne's son and Tyrone Power's daughter, so I put them together. Pat did the best he could, but, frankly, he was only adequate. We had him grow a beard, and he looked fine, but as soon as he opened his mouth, we were in trouble".[6]

The film went into production under the working title Sinbad at the World's End.[11] The live action was filmed in Almería, Spain; Malta; and Jordan.[12] The treasury house of Al Khazneh at Petra makes an appearance in one scene.[13] Several castles near Mdina, Malta, were used as backdrops for the film and inserted using triple-exposure,[14] and scenes of ships at sea were filmed in a huge water tank there.[15] Most interior sequences were shot on a soundstage of Verona Studios near Madrid (Spain).[16][17] Principal filming took place between June and October 1975.[18] Some sets were based on previous films in a wide variety of genres. The massive doors and deadbolt to the ancient shrine of the Arimaspi in the arctic were based on a similar set of doors in 1933's King Kong. The interior of the shrine was very similar to the shrine set in the 1935 motion picture She, complete with steep pyramidal steps, a vortex of light coming from above, and a smilodon encased in ice.[19] The power source of the shrine of Arimaspi was actually made of dental floss. Harryhausen and the crew mounted dozens of floss fiber strands around a cylinder-like construction made of gauze, and this was mounted on a revolving mechanism and put in front of black velvet. It was then pulled out of focus to create shimmering and an inky light was run up and down the system to give it reflections.[20]

Harryhausen originally planned for an Arsinoitherium to make an appearance in the film. The massive, two-horned prehistoric rhinoceros-like creature was intended to fight the troglodyte in Hyperborea's land before the latter meeting with the protagonists. Harryhausen did preproduction designs showing the beast defeating the troglodyte, then getting caught and dying in a pool of hot tar.[19] Harryhausen also said he planned to have Sinbad and his crew fight a yeti in the arctic, but that idea was ultimately rejected in favor of a giant walrus.[21] Other Harryhausen's ideas were a woolly mammoth as the creature which Sinbad's crew meet in the arctic. Harryhausen's stop-motion animation work lasted from October 1975 up to March 1977.

The stop-motion troglodyte figurine used in the film was later cannibalized to make the Calibos character in Harryhausen's 1981 film, Clash of the Titans.[19]

The film featured a nude sunbathing scene by Jane Seymour. According to Schneer: "The nudity came about in the development of the picture. I wanted to keep up with those elements that had become plausible".[6]

Home media

[edit]Blu-ray ALL America – Twilight Time – The Limited Edition Series[22]

- Picture Format: 1.85:1 (1080p 24fps) [AVC MPEG-4]

- Soundtrack(s): English (DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1)

- Subtitles: English

- Extras:

- Isolated Score (DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1)

- This is Dynamation (Featurette) (3:25, 480p)

- Theatrical Trailer (2:15, 1080p)

- Case type: Keep Case

- Notes: Limited to 3,000 copies (none are numbered)

DVD R1 America – Columbia/Tri-star Home Entertainment[23]

- Picture Format: 1.85:1 (Anamorphic) [NTSC]

- Soundtrack(s): English Dolby Digital 2.0 mono

- Subtitles: Chinese, English, Korean, Portuguese, Spanish and Thai

- Extras:

- Theatrical trailer

- Ray Harryhausen Chronicles – Documentary (57:53 min.)

- This is Dynamation (vintage extended trailer, originally used as a teaser for The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, 3:27 min.)

- Bonus trailers: 20 Million Miles to Earth, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Jason and the Argonauts, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers and The 3 Worlds of Gulliver

- Cast & crew filmographies and biographies

- Booklet, with production notes

- Case type: Keep Case

- Notes: Also in a 3-disc The Sinbad Collection box set, with The Golden Voyage of Sinbad and The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.

Critical reception

[edit]

The film was released in the same summer as the original Star Wars film, and suffered in comparison to that science fiction epic.[24]

Reviewer Lawrence Van Gelder, writing for The New York Times, called the acting "rudimentary", but found the film enjoyable: "...this latest Sinbad adventure maintains the innocent and atavistic juvenile charm of the others in the series".[12] Reviewer Lorna Sutton said the film was "pure escapist entertainment which doesn't require serious analysis or criticism". She found the film enjoyable, despite its flaws: "The plot is familiar, the characters are predictable and dialogue is trite. But the action and the special effects provide for a fast-paced two hours of entertainment".[25]

Five years after its release, an anonymous reviewer for the Ottawa Citizen described the film as a "bad umpteenth entry" in the series, and slowly paced.[26] Linda Gross in the Los Angeles Times was kinder, declaring it "a fantasy laced with nostalgia and corn".[27] In another retrospective review, Alan Jones of the Radio Times awarded the film three stars out of five, arguing that it "may not be up to the standard of the previous two Sinbad adventures—it's too long and Patrick Wayne is a distinctly charisma-free hero—but there's still plenty of pleasure to be had from the special effects of Ray Harryhausen".[28] Halliwell's Film Guide described it as a "lumpish sequel to a sequel: even the animated monsters raise a yawn this time".[29]

Some modern reviewers find the stop-motion work lackluster compared to previous Harryhausen films. Harryhausen biographer Roy P. Webber found the ghouls highly derivative of the skeleton warriors from Jason and the Argonauts, with the heads strongly reminiscent of the Selenites from Harryhausen's 1964 effort, First Men in the Moon.[30] He also found the Minoton and the giant wasp to be lacking in character and so ancillary to the plot as to be dismissed.[31] Harryhausen later admitted that the picture was too rushed, which led to many characterization problems in the animation.[32]

Other cinematic effects in the film have also been criticized. Webber, for example, notes that the traveling mattes used in the film to include various filmed elements are very poorly done, and the special effects used to show Zenobia transforming into a gull are "so bad that it is truly laughable".[31]

However, some aspects of the film have received enduring praise. Webber notes that the baboon animation was so good that many people were fooled into believing a real animal had been used. The battle between the troglodyte and the smilodon is much better choreographed than the battle between the one-eyed centaur and the griffin in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, and much more dramatic (with the cat actually raking with its claws and biting with its teeth, leaving deep wounds on its opponent).[31]

References

[edit]- ^ Spencer, Kristopher. Film and Television Scores, 1950–1979: A Critical Survey By Genre. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2008, p. 177.

- ^ "Starts Today! Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger". Detroit Free Press. 25 May 1977. p. 30.

- ^ Mitchell, Steve. "Ray Harryhausen: 'Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger'". Filmmakers. 10 (20): 5.

- ^ a b Mills, Bart (16 September 1979). "ILLUSIONS, FANTASIES AND RAY HARRYHAUSEN". Los Angeles Times. p. n30.

- ^ a b Webber, Roy P. The Dinosaur Films of Ray Harryhausen: Features, Early 16mm Experiments and Unrealized Projects. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2004, p. 193.

- ^ a b c Swires, Steve (March 1990). "Merchant of the Magicks Part Three". Starlog. p. 67.

- ^ "Where Are They Now? 'Wars' Supporting Cast", Sacramento Bee. 31 January 1997.

- ^ A casting director had seen a newspaper story about men with big feet, which featured Mayhew. He tracked him down, and offered him the part of the robotic creature. See: Jenkins, Garry. Empire Building: The Remarkable Real-Life Story of 'Star Wars'. Secaucus, N.J.: Carol Publishing Group, 1999, p. 88.

- ^ "Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) – Full cast and crew". IMDb.

- ^ "Patrick Wayne Will Star in New Dynarama Production". Los Angeles Times. 27 May 1975. p. e10.

- ^ Young, R.G. The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film: Ali Baba to Zombies. New York: Applause, 1997, p. 570.

- ^ a b Van Gelder, Lawrence. "Kids Will Like Third 'Sinbad'". The New York Times., 13 August 1977.

- ^ Miller, Thomas Kent. Allan Quatermain at the Crucible of Life. Rockville, Maryland: Wildside Press, 2011, p. 272.

- ^ Mitchell, p. 24.

- ^ Knapp, Laurence F. Ridley Scott: Interviews. Jackson, Ms.: University Press of Mississippi, 2005, p. 124.

- ^ Gil, Miguel 1st Asst. Director of the film

- ^ Elley, Derek, ed. The 'Variety' Movie Guide. New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1991, p. 549.

- ^ Hell, Richard. The World of Fantasy Films. South Brunswick, N.J.: Barnes, 1980, p. 67.

- ^ a b c Webber, p. 196.

- ^ Dalton, Tony. Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life. London: Aurum, 2003, pgs. 250-252.

- ^ Dalton, Tony. The Art of Ray Harryhausen. London: Aurum, 2005, p. 162.

- ^ Blu-ray.com

- ^ Dvdcompare.net

- ^ Kinnard, Roy. Beasts and Behemoths: Prehistoric Creatures in the Movies. Metuchen, N.J. : Scarecrow Press, 1988, p. 150.

- ^ Sutton, Lorna. "Film Review: Sinbad's Voyage Adventure In Fun". Spokane Spokesman-Review. 29 August 1977.

- ^ "Movies in Review". Ottawa Citizen. 21 August 1982.

- ^ Gross, Linda. "Movies of the Week". Los Angeles Times. 6 September 1981.

- ^ Jones, Alan. "Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger". Radio Times. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ Halliwell, Leslie (1997). Halliwell's Film and Video Guide (paperback) (13 ed.). HarperCollins. p. 702. ISBN 978-0-00-638868-5.

- ^ Webber, p. 197-198.

- ^ a b c Webber, p. 198.

- ^ Dalton, p. 184.

External links

[edit]- 1977 films

- 1970s fantasy adventure films

- British fantasy adventure films

- Seafaring films

- 1970s English-language films

- Films directed by Sam Wanamaker

- Films based on Sinbad the Sailor

- 1970s monster movies

- British monster movies

- Films using stop-motion animation

- Films set in the Arctic

- Films set in 8th-century Abbasid Caliphate

- Columbia Pictures films

- Films shot in Almería

- Films scored by Roy Budd

- American fantasy adventure films

- American monster movies

- Films about shapeshifting

- Films produced by Ray Harryhausen

- Films with screenplays by Ray Harryhausen

- Films produced by Charles H. Schneer

- Films with screenplays by Beverley Cross

- Minotaur in popular culture

- 1970s American films

- 1970s British films

- English-language fantasy adventure films