Six limbs (Indian Painting)

The six limbs of Indian painting or Shadanga in Sanskrit (Devnagari: षडांङ्ग IAST: Ṣaḍaṅga) refer to a classical framework outlining the essential principles and techniques in traditional Indian art.[1] These guidelines were first codified in ancient Sanskrit texts and have significantly influenced the aesthetics and methods of Indian painting over centuries. One of the earliest mention of Ṣaḍaṅga is founded in the Kamasutra[2][Note 1] of Vātsyāyana. The six limbs encompass various aspects, including form, proportion, and expression, serving as a comprehensive guide for artists to create works that are both technically proficient and spiritually profound.[3]

| Art forms of India |

|---|

|

Etymology[edit]

The term Ṣaḍaṅga is derived from Sanskrit, where Ṣaḍ means six[4] and Aṅga means limbs or parts.[5] This term collectively refers to the six foundational principles or limbs that constitute the core guidelines for traditional Indian painting. Each of these limbs addresses a specific aspect of artistic creation, combining to form a comprehensive framework for artists.

Historic Development[edit]

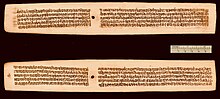

The concept of the Six Limbs of Indian Painting, or Ṣaḍaṅga, finds its roots in ancient Indian texts and treatises on art and aesthetics, reflecting a holistic approach to artistic creation. These principles were initially articulated in Vedic literature,[7][8] which laid foundational ideas about beauty, form, and expression. Detailed elaborations on these principles can be found in later texts such as the Chitrasutra of the Vishnudharmottara Purana, dating back to around the 6th century CE.[9]

The Kamasutra by Vatsyayana,[2] composed in the same period, provides additional insights into the cultural and philosophical underpinnings that influenced Indian art. Besides its renowned discourse on human sexuality, the Kamasutra categorizes arts or Kalā into 64 types,[10][11][12] with painting ranked as the fourth among these arts.[13][14] This classification underscores the esteemed position of painting as a refined and significant art form within ancient Indian society, alongside other disciplines such as sculpture, music, and dance.[15]

In the classical period, the Ṣaḍaṅga principles became integral to the training of artists and the creation of artworks across various schools of Indian painting, such as the celebrated Ajanta murals,[16] Rajput miniatures, and Mughal paintings.[17] Each school interpreted Ṣaḍaṅga according to its cultural milieu, resulting in a diverse range of artistic styles that reflected regional and historical contexts.

During the medieval period, under the influence of the Mughal Empire, Ṣaḍaṅga principles continued to evolve through the synthesis of indigenous techniques with Persian artistic traditions. This cultural syncretism led to the development of distinctive forms like the Mughal miniatures, characterized by their meticulous attention to detail and nuanced expression.[18]

In the modern era, there has been a renewed appreciation and study of Ṣaḍaṅga principles among contemporary artists and scholars. This revival reflects a broader interest in traditional Indian art forms and a commitment to preserving the cultural heritage embodied in these ancient guidelines. Today, artists and historians continue to explore and interpret Ṣaḍaṅga principles, ensuring their relevance and continuity in contemporary artistic practices.

Six Limbs[edit]

Vatsyayana's Kamasutra has following shloka which describes the six limbs of the art:

|

Original Sanskrit रूपभेदः प्रमाणानि भावलावण्ययोजनम । |

Transliteration of verse rūpabhedaḥ pramāṇāni bhāvalāvaṇyayojanam |

Translation The six limbs of painting are: Differentiation of form, Proportion, Infusion of emotions, Gracefulness in composition, Similitude and Use of color. |

The Ṣaḍaṅga provide a detailed framework for the creation and evaluation of art, emphasizing both technical prowess and aesthetic depth. Each limb represents a distinct aspect of the artistic process, ensuring that the artwork is harmonious, expressive, and visually compelling.

Rūpabheda (Form and Proportion)[edit]

Rūpabheda involves the differentiation and depiction of forms. It is the foundation of visual accuracy and realism in art. This principle emphasizes the importance of understanding the anatomy and structure of different forms, whether human, animal, or inanimate. Artists study various shapes and their proportions to render them accurately. This knowledge allows them to depict figures and objects in a way that is true to their natural appearance. The ability to distinguish subtle differences in form is crucial for creating lifelike and dynamic compositions.[19]

Pramāṇa (Measurement)[edit]

Pramāṇa focuses on the precise measurement and proportion of the subjects within the artwork. Correct proportions are essential for maintaining balance and harmony in the composition. They ensure that the elements of the painting relate to each other in a visually pleasing manner. Artists use grids, mathematical calculations, and comparative measurements to achieve accurate proportions. This practice is vital in both figural and architectural representations, where scale and symmetry play crucial roles in the overall aesthetic.[20]

Bhāva (Expression and Emotion)[edit]

Bhāva pertains to the portrayal of emotions and expressions, capturing the inner life of the subjects. This limb is crucial for conveying the narrative and emotional depth of the artwork. It engages the viewer on a psychological level, allowing them to connect with the depicted characters and scenes. Artists study facial expressions, body language, and gestures to accurately represent emotions such as joy, sorrow, anger, and serenity. The ability to evoke the intended emotional response in the viewer is a testament to the artist's skill.[21][22][23]

Lāvaṇya Yojanam (Aesthetic Composition)[edit]

Lāvaṇya Yojanam involves the creation of beauty and aesthetic appeal through the harmonious arrangement of elements. This principle ensures that the artwork is not only technically sound but also pleasing to the eye. It encompasses the overall design, balance, and visual flow of the composition. Artists consider factors such as symmetry, rhythm, and contrast to create a cohesive and attractive composition. The use of visual principles like the rule of thirds, leading lines, and focal points helps in achieving an aesthetically balanced artwork.[24]

Sādhārana (Depiction of Everyday Life)[edit]

Sādhārana focuses on representing common, everyday subjects, grounding the artwork in the realities of daily life. This limb emphasizes relatability and accessibility, making the artwork resonate with the viewer's own experiences and surroundings. Artists depict scenes from daily life, such as market activities, domestic chores, and social interactions. This practice not only adds realism but also reflects the cultural and societal contexts of the time, providing valuable insights into the artist's world.[25]

Varnikābhanga (Use of Color)[edit]

Varnikābhanga involves the application, blending, and harmonization of colors to enhance the visual and emotional impact of the painting. Color is a powerful tool in art, capable of conveying mood, atmosphere, and symbolic meaning. Mastery of color usage can transform a composition, adding depth and vibrancy. Artists study color theory, including the relationships between colors, such as complementary and analogous colors. They also explore techniques for creating gradients, shading, and highlights to add dimension and realism. The careful selection and application of colors help in setting the tone of the painting and guiding the viewer's emotional response.[26][27]

These six limbs collectively form a holistic approach to art, ensuring that each piece is not only a display of technical skill but also a profound expression of beauty, emotion, and cultural significance. By adhering to the Ṣaḍaṅga, artists can create works that are deeply resonant and enduring.

Influence[edit]

The principles of Ṣaḍaṅga have been revered and celebrated by artists, scholars, and patrons of Indian art over centuries. Abanindranath Tagore,[28] prominent artist of the Bengal School of Art,[29] played a significant role in revitalizing traditional Indian art forms. His works reflect a deep appreciation for Indian aesthetic principles. Known for his realistic portrayal of Indian mythology and everyday life, Raja Ravi Varma's[30][31] paintings often embody the principles of form, expression, and aesthetic composition inherent in Ṣaḍaṅga. Another key figure of the Bengal School, Nandalal Bose contributed to the modern interpretation and propagation of traditional Indian art techniques, emphasizing principles of proportion, emotion, and color harmony. An influential British art historian and curator, E. B. Havell wrote extensively on Indian art and its spiritual and aesthetic principles.[32] His writings helped popularize Indian art traditions, including Ṣaḍaṅga, among Western audiences. A Sri Lankan Tamil philosopher and art historian, Ananda Coomaraswamy's scholarly works on Indian art and aesthetics provided insightful interpretations of Ṣaḍaṅga principles,[1] contributing to their broader appreciation and understanding. Renowned for his bold and innovative approach to folk art-inspired paintings, Jamini Roy integrated traditional Indian artistic principles with modern sensibilities, showcasing a fusion of Ṣaḍaṅga elements in his artworks. A modernist painter and founding member of the Progressive Artists' Group, S. H. Raza's works often reflect a synthesis of Indian spiritual traditions and modern abstract forms, highlighting elements of Ṣaḍaṅga in new contexts.[33]

These artists and scholars, among others, have contributed to the preservation, reinterpretation, and celebration of Ṣaḍaṅga principles in Indian art, affirming their enduring relevance and influence in the realm of artistic expression.

Reception[edit]

The Six Limbs of Indian Painting, or Ṣaḍaṅga, have been widely recognized and celebrated for their profound influence on Indian art and aesthetics. Since their inception in ancient Sanskrit texts, these principles have shaped the development of various painting styles across different historical periods and regions of India.

The historical legacy of Ṣaḍaṅga underscores its enduring relevance and foundational role in Indian art, serving as a touchstone for artists and scholars seeking to understand and preserve traditional artistic practices. Ṣaḍaṅga embodies broader cultural values and philosophies inherent to Indian aesthetics, emphasizing principles such as balance, harmony, and the expressive portrayal of emotion . These principles not only guide artistic creation but also reflect deeper spiritual and philosophical insights into the interconnectedness of art, nature, and human experience.[34]

Over centuries, Ṣaḍaṅga has been adapted and interpreted by various regional and cultural traditions within India, leading to a diverse array of painting styles and techniques. The principles have shown remarkable adaptability, evolving with influences from Persian, Buddhist, and other artistic traditions, while maintaining their core values of form, expression, and aesthetic composition. In recent times, there has been a renewed interest in traditional Indian art forms, including a revival of Ṣaḍaṅga principles among contemporary artists and scholars. Institutions and organizations dedicated to art preservation and promotion actively study and promote Ṣaḍaṅga, ensuring its continued relevance and integration into modern artistic practices.

Beyond India, Ṣaḍaṅga principles have garnered international recognition for their unique approach to art theory and practice. They contribute to a broader understanding of global art history, highlighting India's significant contributions to artistic techniques, aesthetics, and philosophical thought. The renowned British artist and art critic, William George Archer, is known for his praise of the Shadanga, the six limbs of Indian painting.[35] Archer's work and critique played a significant role in bringing attention to the rich heritage of Indian art and its theoretical frameworks. Another prominent international artist who praised the Shadanga of Indian painting is Okakura Kakuzō, a Japanese art historian and critic.[36] He was deeply influenced by Indian art and philosophy and acknowledged the profound impact of Indian aesthetics on broader Asian art traditions. His writings and advocacy helped elevate the appreciation of Indian artistic principles, including the Shadanga, within the global art community.[37]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Vātsyāyana, was an Indian logician who studied human sexuality in detail, and wrote Kamasūtra. However, it doesn't only include human sexuality, but also human nature and aspects of human life, which is termed as Kalā or skill. Kamasutra describes 64 types of kalā, where painting is ranked on fourth. Shadanga is described as an important aspect of the painting.

- ^ Vātsyāyana's idol at a Himalayan Boutique Resort. Very little is known about the life and depictions of Vatsyayana.

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. (2003). History of Indian and Indonesian Art. Kessinger Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7661-5801-6. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ a b Mallanaga, Vatsyayana (1 January 1994). The Complete Kāma-Sūtra. Translated by Daniélou, Alain. Park Street Press. p. 576. ISBN 9780892816804.

- ^ Chaitanya, Krishna (1994). A History of Indian Painting: The Modern Period. Abhinav Publication. p. 330. ISBN 8170173108.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (9 May 2018). "Shash, Ṣaṣ, Sash, Śas, Śās, Ṣaḍ, Śāḍ, Śaṣ, Śad, Shas, Shad: 29 definitions". www-wisdomlib-org.translate.goog. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (11 April 2009). "Anga, Aṅga, Amga: 54 definitions". www-wisdomlib-org.translate.goog. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Welch, Ms Sarah (28 October 2018), English: The Kama Sutra is a Hindu text, whose title literally means "a treatise on desire / emotional pleasure / love / sex". It is likely a 3rd- or 4th-century CE text according to scholars, but some estimates place it centuries before or after that range. It is a Sanskrit text by Vatsyayana Mallanaga. Vatsyayana mentions in the Kama Sutra that his work relies on earlier Kama sastra texts. He cites them, but these older texts have not survived into the modern era. The Kamasutra exists in many Indic scripts. Being a sutra, it is terse and distilled., retrieved 24 June 2024

- ^ "Veda | Definition, Scriptures, Books, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 21 June 2024. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Dehejia, Authors: Vidya. "Hinduism and Hindu Art | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ श्रीविष्णुधर्मोत्तरमहापुराणम् (संस्कृत एवं हिंदी अनुवाद)- Shri Vishnudharmottara Purana (in Sanskrit) (2016 ed.). CHAUKHAMBA SURBHARATI PRAKASHAN. p. 2230. ISBN 9789385005466.

- ^ "कामसूत्र की 64 कलाएं क्या हैं, जिन्हें जानने वाला कभी कहीं नाकाम नहीं रहेगा". News18 हिंदी (in Hindi). 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "64 Arts of Kamasutra". Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Ketutar (10 February 2019). "The List: The 64 Arts Of The Kama Sutra (not sex)". The List. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Impact of Kamasutra on The Temple Art & Sculpture of Odisha | Exotic India Art". www.exoticindiaart.com. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "31 Kamsutra ideas | indian paintings, indian art, india art". Pinterest. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Bharadwaj, Chandrashekhar. भारतीय समाज, कला एवं संस्कृति [Indian Society, Art and Culture] (in Hindi) (2021 ed.). Delhi: Vishwa Bharati Publications. p. 208. ISBN 9789381907290.

- ^ Lal, Anand, ed. (2004). The Oxford Companion to Indian Theatre. Oxford University Press. pp. 15, 415, 449–450. ISBN 9780195644463.

- ^ "Indian Miniature Paintings: The Mughal and Persian Schools – Google Arts & Culture". Google Cultural Institute. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Haider, Sanobar (21 July 2017). "Mughal Painting". Mughal Painting: 3.

- ^ Goetz, Hermann (1937). "An Indian Element in 17th Century Dutch Art". Oud Holland - Quarterly for Dutch Art History. 54 (1): 220–230. doi:10.1163/187501737x00281. ISSN 0030-672X.

- ^ Mitter, Partha (2001). Indian Art. Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 9780192842213.

- ^ "Bhāva | Indian arts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Bhava and Rasa in Bharata's Natyasastra". Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "The Six Limbs of Indian Art". Art Debates. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (6 April 2019). "Lavanyayojana, Lāvaṇyayojana, Lavanya-yojana: 2 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ L. Huntington, Susan; C. Huntington, John (2014). The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain (1st ed.). p. 815. ISBN 9788120836174.

- ^ "Welcome to National Book Trust India". www.nbtindia.gov.in. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Mitra, Swarna (24 July 2014). Color Indian Art: 7 (World Culture Coloring). Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1500485726.

- ^ "Abanindranath Tagore - 15 artworks - painting". www.wikiart.org. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Molcard, Eva Sarah (1 March 2019). "How the Bengal School of Art Gave Rise to Indian Nationalism". Sothebys.com. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Raja Ravi Varma - 51 artworks - painting". www.wikiart.org. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Raja Ravi Varma". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Havell, E.B. The Ideals of Indian Art (2018 ed.). New Delhi: K. N. Book House. ISBN 9381825041.

- ^ "Modern Indian Art - Principles of design". SlideShare. 7 March 2024. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "South Asian arts - Indian Painting, Mughal, Rajput | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Archer, William George (1959). India and Modern Art. Allen & Unwin.

- ^ Shigemi, Inaga; Singleton, Kevin (2012). "Okakura Kakuzō and India: The Trajectory of Modern National Consciousness and Pan-Asian Ideology Across Borders". Review of Japanese Culture and Society. 24: 39–57. ISSN 0913-4700.

- ^ Limited, Alamy. "Okakura kakuzo hi-res stock photography and images". Alamy. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

This article has not been added to any content categories. Please help out by adding categories to it so that it can be listed with similar articles. (June 2024) |