Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham

Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS),[a] also referred to as Tahrir al-Sham, is a Sunni Islamist political organisation and militia involved in the Syrian civil war.[59][60][61][43] It was formed on 28 January 2017 as a merger between several armed groups: Jaysh al-Ahrar (an Ahrar al-Sham faction), Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (JFS), Ansar al-Din Front, Jaysh al-Sunna, Liwa al-Haqq, and the Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement.[3][62] The unification process was held under the initiative of Abu Jaber Shaykh, an Islamist militant commander who had been the second emir of Ahrar al-Sham. HTS, along with other Syrian opposition groups, launched an offensive and toppled the Assad regime on 8 December 2024, and now controls most of the country.[3]

Proclaiming the nascent organisation as "a new stage in the life of the blessed revolution", Abu Jaber urged all factions of the Syrian opposition to unite under its Islamic leadership and wage a "popular jihad" to achieve the objectives of the Syrian revolution, which he characterised as the ouster of the Ba'athist regime and Hezbollah militants from Syrian territories, and the formation of an Islamic government.[63] After the announcement, additional groups and individuals joined. The merged group has been primarily led by Jabhat Fatah al-Sham and former Ahrar al-Sham leaders, although the High Command also has representation from other groups.[64] The Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement[6] split from Tahrir al-Sham in July 2017, and the Ansar al-Din Front in 2018.[65]

The formation of HTS was followed by a string of assassinations of its supporters. In response, HTS launched a successful crackdown on Al-Qaeda loyalists, which cemented its power in Idlib. HTS has since been pursuing a "Syrianisation" programme, focused on establishing a stable civilian administration that provides services and connects to humanitarian organizations in addition to maintaining law and order.[62] Tahrir al-Sham's strategy is based on expanding its territorial control in Syria, establishing governance and mobilising popular support. In 2017, HTS permitted Turkish troops to patrol North-West Syria as part of a ceasefire brokered through the Astana negotiations. Its policies have brought it into conflict with Hurras al-Deen, Al-Qaeda's Syrian wing, including militarily.[66] HTS had an estimated 6,000–15,000 members in 2022.[22]

From 2017 to 2024, Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham gave allegiance to the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), which was an alternative government of the Syrian opposition in the Idlib Governorate.[67][68] While the organisation officially adheres to the Salafi school, the High Council of Fatwa of the Syrian Salvation Government – to which it is religiously beholden – consists of ulema from Ash'arite and Sufi traditions as well. In its legal system and educational curriculum, HTS implements Shafi'ite thought and teaches the importance of the four classical Sunni madhahib (schools of law) in Islamic jurisprudence.[69] After the fall of Damascus, the SSG was replaced by the Syrian transitional government. From 2021 to the fall of Assad, HTS was the most powerful military faction within the Syrian opposition.[70] Τhe organisation was designated a terrorist group by United Nations Security Council Resolution 2254,[71] which classified the group's precursor, Al-Nusra Front.[72]

History

| Part of a series on |

| Jihadism |

|---|

|

|

Predecessors

Before becoming the emir of al-Nusra Front, Abu Mohammad al-Julani started his military career in 2003, travelling from Damascus in Syria to Iraq, where he resisted the U.S. occupation of Iraq. He joined al-Qaeda in Iraq and fought in the Iraqi insurgency against the American occupation.[73][74] After his imprisonment by U.S. military in 2006 and subsequent release by Iraqi government in 2011 during the Syrian revolution, Julani was tasked with establishing al-Nusra Front as al-Qaeda's official branch in Syria. Between 2011 and 2012, he co-ordinated with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), to expand al-Qaeda's branch in Syria.[74][75][73]

In April 2013, Baghdadi announced his group's expansion into Syria and declared the creation of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and unilaterally demanded al-Nusra's merger into ISIL. Julani denounced the move; and maintained his bay'ah (trans: "pledge of allegiance") to al-Qaeda.[73] Al-Qaeda emir Ayman al-Zawahiri also denounced al-Baghdadi's announcement, asserting that Syria was the "spatial state" of the Al-Nusra Front. Zawahiri officially demanded the dissolution of the new entity and urged Baghdadi to withdraw all his troops from Syria.[76][77][78] In a letter addressed to the leaderships of ISIL and al-Nusra Front on June 2013, Ayman al-Zawahiri directly rebuked al-Baghdadi's moves by recognizing al-Nusra Front as the only official Syrian branch of al-Qaeda and demanded the dissolution of ISIL.[79][76]

By January 2014, hostile rhetoric between ISIL and al-Nusra Front escalated into violent conflict.[80][81] Al-Nusra Front formally cut all factional links to ISIL in February 2014 when al-Qaeda's general command issued an official statement disavowing and terminating all relations with ISIL.[82][77][83] In July 2016, al-Nusra Front under Julani split from al-Qaeda, rebranding as Jabhat Fatah al-Sham.[84][85]

Background

Al-Nusra Front/Jabhat Fateh al-Sham co-operated with Ahrar al-Sham throughout most of 2015 and 2016. Leading Ahrar al-Sham cleric Abu Jaber saw al-Nusra's affiliation to al-Qaeda as detrimental to their cause. He also sought to unify Islamist rebel factions.[86][3][87] He led a more Islamist and less nationalist faction within Ahrar al-Sham, Jaysh al-Ahrar, which supported a merger with Jabhat Fateh al-Sham. There were merger talks in late 2016, but these broke down. In early 2017, Jaysh al-Ahrar clashed with rival Islamist groups in Idlib, particularly Ahrar al-Sham, before separating from Ahrar al-Sham to merge with Jabhat Fateh al-Sham in a new body.[88]

Formation

Upon its founding, HTS was described by its emir, Abu Jaber Shaykh, as "an independent entity" formed through the unification of previous groups and factions.[89]

Charles Lister, an analyst specialising in Syria, noted that Ahrar al-Sham lost around 800–1,000 defectors to HTS but gained 6,000–8,000 fighters through the merger of Suqor al-Sham, Jaish al-Mujahideen, the Fastaqim Union, the western Aleppo units of the Levant Front, and the Idlib-based units of Jaysh al-Islam. JFS lost several hundred fighters to Ahrar al-Sham but gained 3,000–5,000 fighters from its merger with Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zinki, Liwa al-Haq, Jaish al-Sunna, and Jabhat Ansar al-Din into HTS.[88] Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zenki previously received support from the United States.[90]

Consolidation of power (January–August 2017)

January

Throughout January 2017, intense fighting broke out between the JFS and al-Qaeda loyalists of al-Nusra Front, before the JFS-Ahrar al-Sham merger to form HTS on January 28. Soon after the merger, Emir Abu Jaber Shaykh announced a ceasefire deal aimed at uniting all opposition militia factions under a central command. The creation of HTS was described as by the Henry Jackson Society as a reshaping of dynamics since the 2011 Syrian Revolution, with a potential to shift the balance of power in the Syrian civil war and diminish al-Qaeda's influence in northern Syria.[91] Between 2017 and 2019, HTS launched a series of crackdowns against al-Qaeda loyalists while also targeting Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) cells through military operations.[92]

On 30 January, Asharq al-Awsat reported that HTS had approximately 31,000 fighters, bolstered by the inclusion of Jaysh al-Ahrar, a breakaway faction of the Ahrar al-Sham militia.[18]

February

On 3 February, a US airstrike struck a Tahrir al-Sham headquarters in Sarmin, killing 12 members of HTS and Jund al-Aqsa. 10 of the killed militants were HTS members.[93][94]

Civilians in the rebel regions that HTS controls have resisted it. On 3 February, hundreds of Syrians demonstrated under the slogan "There is no place for al-Qaeda in Syria" in the towns of Atarib, Azaz, Maarat al-Nu'man to protest against HTS. In response, supporters of HTS organized counter-protests in al-Dana, Idlib, Atarib, and Khan Shaykhun.[95] In Idlib pro- Hayyat Tahrir al-Sham protests were held waving pictures of its emir Abu Jaber on 3 February 2017.[96]

On 4 February 2017, a US airstrike killed former al-Qaeda commander Abu Hani al-Masri, who was a part of Ahrar al-Sham at the time of his death. It was reported that he was about to defect to Tahrir al-Sham before his death.[94] Around 8 February, Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi confirmed that 2 senior Jabhat Fateh al-Sham leaders loyal to al-Qaeda, including former al-Nusra deputy leader Sami al-Oraydi, left Tahrir al-Sham after its formation.[97]

A speech was released by Abu Jaber on 9 February.[98] He emphasized his group being an "independent entity" and praised his "brothers" in the "Syrian Jihad" for their "heroic" resistance against Ba'athist forces, Hezbollah and Russians. The statement urged all opposition factions to join forces with HTS and warned Syrian Sunnis; asserting that Iran will "enslave the region" if the rebels lose the war.[1]

On 12 February, the Bunyan al-Marsous Operations Room, of which Tahrir al-Sham was a member, launched an offensive against the Syrian Army in Daraa's Manshiyah district. Tahrir al-Sham forces reportedly began the attack with 2 suicide bombers and car bombs.[99]

On 13 February, clashes erupted between the previously allied Tahrir al-Sham and Jund al-Aqsa, also called Liwa al-Aqsa, in northern Hama and southern Idlib.[100][101]

On 15 February, Ahrar al-Sham published an infographic on its recent defections, claiming that only 955 fighters had defected to Tahrir al-Sham.[97] On 22 February, the Combating Terrorism Center reported that Jabhat Fateh al-Sham had formed the Tahrir al-Sham group due to its fear of being isolated, and to counter Ahrar al-Sham's recent expansion during the clashes in the Idlib Province.[97]

On 22 February, the last of Liwa al-Asqa's 2,100 militants left their final positions in Khan Shaykhun, with unconfirmed reports in pro-government media that they were to join ISIL in the Ar-Raqqah Province after a negotiated withdrawal deal with Tahrir al-Sham and the Turkistan Islamic Party.[102] Afterward, Tahrir al-Sham declared terminating Liwa al-Aqsa, and promised to watch for any remaining cells.[103]

On 26 February, a US airstrike in Al-Mastoumeh, Idlib Province, killed Abu Khayr al-Masri, who was the deputy leader of al-Qaeda.[104][105] The airstrike also killed another Tahrir al-Sham militant.[106][107] Abu Khayr's death left HTS freer to move away from al-Qaeda's any remaining influence.[88]

March

In early March 2017, local residents in the Idlib Province who supported FSA factions accused Tahrir al-Sham of doing more harm than good, saying that all they've done is "kidnap people, set up checkpoints, and terrorize residents".[108]

On 16 March, a US airstrike struck the village of al-Jinah, just southwest of Atarib, killing at least 29 and possibly over 50 civilians; the US claimed the people targeted in the strike were "al-Qaeda militants" but the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), local residents and local officials have said that the building struck was a mosque filled with worshipers, which was subsequently confirmed by Bellingcat.[109][110][111]

On the morning of 21 March, according to pro-government media, a US drone strike in Darkush, Idlib Province, killed Abu Islam al-Masri, described as an Egyptian high-ranking HTS commander, and Abu al-'Abbas al-Darir, described as an Egyptian HTS commander;[112] however, the Institute for the Study of War reported that the commander killed was Sheikh Abu al-Abbas al-Suri.[113]

On 24 March, two flatbed trucks carrying flour and belonging to an IHH-affiliated Turkish relief organization were stopped at a HTS checkpoint at the entrance to Sarmada. HTS then seized the trucks and the flour, which was intended for a bakery in Saraqib. The seizure caused 2,000 families in the area to be cut off from a free supply of bread.[114]

April

| Part of a series on Islamism |

|---|

|

|

In April 2017, Jaysh al-Islam attacked HTS and expelled it from the territories under its control in Eastern Ghouta.[115]

On 3 May, HTS arrested Suhail Muhammad Hamoud, "Abu TOW", a former FSA fighter, in a house raid in Idlib. Earlier, al-Hamoud had published a photograph of him smoking in front of a HTS billboard that prohibited smoking.[116]

May

According to reports from pro-government Al-Masdar news, on 20 May, the main faction of the Abu Amara Battalions joined Tahrir al-Sham, which "now boasts a fighting force of some 50,000 militants" according to one pro-government media source.[117] However, the covert operations unit of the Abu Amara Battalions based in Aleppo remained independent.[118]

On 29 May, Tahrir al-Sham arrested opposition activist and FSA commander Abdul Baset al-Sarout after accusing him of participating in an anti-HTS protest in Maarat al-Nu'man.[119]

June

On 2 June 2017, defectors from the Northern Brigade's Commandos of Islam Brigade reportedly joined Tahrir al-Sham, although Captain Kuja, leader of the unit, stated that he is still part of the Northern Brigade.[120][121]

July

During 18–23 July, HTS launched a series of attacks on Ahrar al-Sham positions, which were quickly abandoned.[88] On 20 July 2017, the Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement led by Sheikh Tawfiq Shahabuddin announced its withdrawal from Tahrir al-Sham amid widespread conflict between HTS and Ahrar al-Sham, and became an independent Islamist group.[6] On 23 July 2017, Tahrir al-Sham expelled the remnants of Ahrar al-Sham from Idlib, capturing the entire city[122] as well as 60% of the Idlib Governorate.[123] HTS was now the dominant armed group in opposition-held NW Syria.[88]

August

On 18 August 2017, Tahrir al-Sham captured 8 rebel fighters from the town of Madaya after it accused them of wanting to return to Madaya during a ceasefire agreement.[124]

Attacks (early 2017)

Syrian intelligence commander Hassan Daaboul was among the 40 assassinated by Hayyat Tahrir al-Sham, in twin bomb attacks at complexes of the Ba'athist secret police in Homs.[125] The explosion killed Ibrahim Darwish, a Brigadier General and the state security branch's chief.[126] Abu Yusuf al-Muhajir, a Tahrir al-Sham military spokesman was interviewed by Human Voice on the bombings.[127] Twenty-six names were released.[128] HTS leader Abu Mohammed al-Julani mentioned the Homs attack, stating that it was a message for the "defeatist politicians" to "step aside".[129] It has been disputed that the raid resulted in the death of Ibrahim Darwish.[130]

On 11 March 2017, Tahrir al-Sham carried out a twin bombing attack in the Bab al-Saghir area of Damascus's Old City, killing 76 and wounding 120. The death toll included 43 Iraqi pilgrims, whom HTS claimed were "Iranian militias" supporting Assad regime's dictatorship.[131] The attacks were at a shrine frequented by Shi'ite pilgrims and militiamen.[132] In a statement released the following day, Tahrir al-Sham stated that the attacks targeted Iran-backed militants fight on behalf of Bashar al-Assad and condemned Khomeinist militants for "killing and displacing" Syrians.[133]

Beginning of decline, leadership passes from Abu Jaber (late 2017)

From September to November 2017, there were a series of assassinations of HTS leaders, in particular foreign clerics associated with the most hardline elements, such as Abu Talha al-Ordini, Abu Abdulrahman al-Mohajer, Abu Sulaiman al-Maghribi, Abu Yahya al-Tunisi, Suraqa al-Maki and Abu Mohammad al-Sharii, as well as some local military leaders, including Abu Elias al-Baniasi, Mustafa al-Zahri, Saied Nasrallah and Hassan Bakour. There was speculation that the assassinations were carried out either by pro-Turkish perpetrators, given the hostility between Turkey and HTS in Idlib, or by supporters[who?] of Julani's attempt to turn the organization away from hardline Salafi-jihadi positions. There were also high-profile defections from HTS in the same period, including Abdullah al-Muhaysini and Muslah al-Alyani.[134] In December, HTS arrested several prominent jihadi activists, former members of al-Nusra who remained loyal to al-Qaeda and rejected HTS's turn away from Salafi-jihadist positions. The move was interpreted as an attempt to re-establish as a more pragmatic, pan-Sunni group, with a civilian structure. Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri denounced this turn.[135][136]

HTS announced Abu Jaber's resignation as the group's leader on 1 October 2017. He was succeeded by Nusra Front founder Abu Mohammed al-Julani, who had already been the de facto military commander.[137][138] On 1 October 2017, the ibn Taymiyyah Battalions based in the town of Darat Izza defected from Tahrir al-Sham.[139] In October 2017, Russia claimed to have injured Abu Mohammed al-Joulani in an air raid; HTS denied the claim.[140][138] HTS established the Syrian Salvation Government in Idlib, as a rival to the Syrian Interim Government recognized by other rebels.[115]

In early 2018, there were reports that HTS had been significantly weakened, and now had "a small presence in Eastern Ghouta and declining influence in Idlib, northern Hama, and western Aleppo provinces", with just 250 men in Eastern Ghouta[115] and a total of 12,000 fighters.[88]

In February 2018, Tahrir al-Sham was accused of killing Fayez al-Madani, an opposition delegate tasked with negotiations with the government over electricity delivery in the northern Homs Governorate, in the city of al-Rastan. Hundreds of people, including fighters of the Men of God Brigade, part of the Free Syrian Army's National Liberation Movement group,[141][142][143] proceeded to demonstrate against HTS in the city on 13 February. In response, HTS withdrew from Rastan and handed over its headquarters in the city to the Men of God Brigade.[144] Meanwhile, Al-Qaeda loyalists formed the anti-HTS Guardians of Religion Organization (Hurras al-Din) in February 2018, establishing it as the successor group of Al-Nusra Front.[145]

HTS was left excluded from the 24 February ceasefire agreement on Eastern Ghouta. In late February, a group of armed factions, including Failaq al-Rahman and Jaysh al-Islam, wrote to the UN declaring they were ready to "evacuate" remaining HTS fighters from Eastern Ghouta within 15 days.[115] At the same time in Idlib Governorate, Ahrar al-Sham, Nour al-Din al-Zinki and Soqour al-Sham entered into conflict with HTS, taking significant territory.[115]

During late 2017 and early 2018, it co-operated with Turkey in Idlib, leading to deepening tensions between the more pragmatic leadership and more hardline (especially foreign fighters) elements hostile to working with Turkey. Some of the latter split in February 2018 to form Huras al-Din. The HTS leadership also cracked down on remaining ISIS splinter cells active in Idlib. By August, when HTS entered into (unsuccessful) negotiations with Russia and Turkey, HTS was estimated to have around 3,000–4,000 foreign fighters, including non-Syrian Arabs, out of a total of 16,000 HTS fighters. On 31 August, Turkey declared HTS a terrorist organization.[86]

By early 2018, HTS had cracked down on the majority of competing factions and established military control over 80% of the greater Idlib area.[146] In the summer of 2018, HTS strengthened its crackdown campaign against cells affiliated with IS organization in Idlib and Hama regions.[92]

2019

Revival and victory in Idlib

In January 2019, HTS was able to seize dozens of villages from rivals, and afterwards, a deal was reached in which the civil administration was to be led by HTS in the whole rebel-held Idlib Governorate.[147]

In the wake of the 5th Idlib inter-rebel conflict, HTS gained control of nearly the entire Idlib pocket, after defeating the Turkish-backed National Front for Liberation. Following their victory, Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham would immediately violate the ceasefire treaty brokered by Turkey and Russia by placing combat units in the demilitarized zone along the Idlib-Syrian Government border, and attack SAA encampments near the area. In response to these attacks, Syrian president Bashar al-Assad increased the number of troops garrisoned near Idlib, which some have argued is an impending renewed offensive in the region, following the Northwestern Syria Campaign, where pro-government forces retook the formerly rebel-controlled Abu al-Duhur Military Airbase that was captured by the FSA and Army of Conquest in 2015. In 2019, the U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary Defense Michael Mulroy stated that "Idlib is essentially the largest collection of al Qaeda affiliates in the world."[148][149][150][151] On July 10–11, 57 pro-government fighters were killed when Tahrir al-Sham militants attacked Syrian positions near the fortified village of Hamamiyat. 44 militants were also killed.[152][153]

2020–2022

Cooperation with Turkey

HTS successfully defended Idlib from 2019 to 2020 government offensives. During this period, HTS cemented its security partnership with the Turkish military against the Assad regime.[70] The opposition and Islamist groups led by HTS suffered heavy losses as a result of the Dawn of Idlib 2 operation launched under the leadership of the Assad regime between December 2019 and March 2020, and many cities and towns from the Idlib Pocket fell under the control of regime forces. During this time, Turkey was protesting the siege of Turkish military observation points deployed according to the Astana agreement by regime forces and wanted Assad to stop his attack on the Idlib region.[154] After 34 Turkish soldiers lost their lives in the Balyut attack carried out by Assad's troops, Turkey launched Operation Spring Shield. As a result of the Turkish counterattack, regime forces and their supporters suffered heavy losses.[155][156] Turkey's counter-offensive halts regime forces advance into Idlib. Taking advantage of this opportunity, the opposition led by HTS launched a counterattack. This cooperation with Turkey prevented HTS and other opposition groups from losing Idlib and forced deportation to the Turkish border.[157][158][159]

On 1 March 2021 it was reported that Hayat Tahrir al-Sham intensified its campaign against al-Qaeda affiliate Hurras al-Din in Idlib.[160] Since 2021, HTS has started implementing various reconstruction projects in areas under its control, with a focus on establishing civil institutions in opposition-held territories. These included the Bab al-Hawa Industrial City project and re-opening of al-Ghazawiya crossing point to connect with the Syrian Interim Government held territories.[161]

After achieving stability in Idlib in 2021, HTS launched the policy of repatriating confiscated properties of minorities in North-West Syria. These also included the re-building of destroyed churches in Idlib. HTS commanders and SSG officials have since initiated regular meetings to engage with priests and representatives the Christian community in Idlib.[162][163]

The Washington Post reported in January 2022 that the group was "trying to convince Syrians and the world that it is no longer as radical and repressive as it once was", voicing rhetoric about combating extremism, and shifting its focus to providing services to the refugees and residents of Idlib province through the Salvation Government.[164] In 7 January, Abu Muhammad al-Joulani announced the inauguration of the Aleppo-Bab al-Hawa International Road, presenting the event as part of "a comprehensive plan... to achieve development and progress for the region".[161]

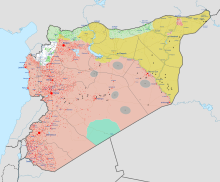

Territories held by Tahrir al-Sham (white) and the Assad regime (red).

In August 2022, HTS ideologue Abu Maria al-Qahtani issued a statement demanding the dissolution of Al-Qaeda and urged all AQ branches to cut ties from the organization.[165] In 2022, HTS took a significant amount of territory and several key settlements during the October 2022 Aleppo clashes.

2023

In 2023, it was reported that Western hostilities towards HTS had decreased, but were still marked by mutual rivalry, due to conflict with American interests in the region.[166] The U.S. State Department alleged in 2023 that the group obstructed humanitarian efforts in Idlib through licensing and registration protocols as well as through the imposition of taxes and fees on Western NGOs and regulations on aid distribution and beneficiary selection.[167]

In a speech before the revolutionary conference of Syrian Salvation Government in May 2023, Joulani announced intentions to transform the strategic map of the conflict. Stating that Tahrir al-Sham has achieved remarkable military preparation, Joulani asserted that "Aleppo is the gate to Damascus and it will be under focus for one or two years."[168] In May 2023, HTS and SDF announced separate proposals to host millions of Syrian refugees stranded across the neighboring countries, following the Arab League's reinstatement of the Assad government.[169]

In June 2023, Tahrir al-Sham and the Syrian Democratic Forces initiated formal diplomatic talks, concluding an agreement to initiate trade of fuel supplies between Rojava and Idlib. The meetings were held against the backdrop of growing tensions between Turkey and SDF, and SDF's intention to deploy HTS as a check on the growing Turkish influence in northern Syria. For their part, HTS proposed joint counter-terrorism efforts alongside SDF. Apart from economic co-operation, the talks also involved negotiations on political arrangements, such as prospects for a joint HTS–SDF civil administration in the event that SNA forces were expelled from North-West Syria.[170]

2024

In November, the HTS launched the Northwestern Aleppo offensive, which it called Operation Deterrence of Aggression reportedly capturing 11 towns and villages in western Aleppo Governorate, capturing the eponymous governorate's capital of Aleppo four days into the offensive.[171][172] By 4 December, HTS had captured most of Aleppo Governorate and Idlib Governorate and began to advance on Hama.[172]

According to Abu Hassan al-Hamwi, commander of HTS's military wing, the offensive resulted from year-long strategic planning and coordination between opposition groups.[173] Prior to the operation, HTS had developed enhanced military capabilities, establishing a dedicated drone unit and indigenous weapons production. The group deployed its newly developed "Shahin" (Arabic for Falcon) suicide drone against regime forces for the first time during the offensive. HTS additionally facilitated the creation of a unified operations room in southern Syria, synchronizing military actions with approximately 25 rebel groups to encircle Damascus from multiple fronts.[173][174]

On 5 December, HTS fighters had captured the city of Hama after two-days of fighting in neighboring villages. The group said it would advance on Homs (40 km from Hama).[175] The next day, it was reported from a rebel commander and pro-rebel media that Tahir al-Sham forces continued to advance on Homs, reportedly reaching 10 km–5 km north of the city.[176]

On 7–8 December, Damascus fell to Syrian opposition forces, including HTS, the Southern Operations Room, and the US-backed Syrian Free Army,[177] and Assad fled to Russia.[178] On 30 December, HTS leader and the de facto leader of Syria Ahmed al-Sharaa announced that the organisation would be dissolved by 4–5 January 2025.[179][180][needs update]

Ideology and governance

Abu Jaber Shaykh, a prominent scholar and chief of the Shura Council of Tahrir al-Sham, was arrested several times by the Ba'athist regime, which accused him of holding Salafi jihadi beliefs. He was imprisoned at Sednaya Prison in 2005 and released in 2011 alongside several jihadist prisoners who later formed Salafist rebel groups during the Syrian civil war.[1] Shaykh advocates for "Popular Jihad," a grassroots approach that focuses on winning popular support before establishing Islamic governance, contrasting with ISIL's "elite Jihad," which relies on a vanguard to lead from the top down.[181] Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi of the Combating Terrorism Center claimed in February 2017 that despite public statements by Tahrir al-Sham's leaders and partisans, the group (at the time) was essentially al-Qaeda-aligned.[97]

On 18 June 2019, HTS released a statement offering condolences to Egypt's former president Muhammad Morsi upon his death in Egyptian custody.[182] In an interview given to the PBS Frontline documentarian Martin Smith, Abu Mohammad al-Julani stated regarding the religious doctrines and political goals of Tahrir al-Sham:[183]

To limit the description of the HTS to only being a Salafist or jihadist, I believe, needs a long discussion. And I don't want to comment on that now, because it would take a lot of research and study. We are trying today to talk about Islam in its real concept, the Islam that seeks to spread justice and aspires for building and for progress, and to protect women and preserve their rights, and for education as well. So if we agree that there's an Islamic rule in the liberated areas, we say that there are universities, by Allah's grace, full of students, two-thirds being female students. There are more than 450,000 to 500,000 students enrolled in schools. There are fully functioning hospitals in the liberated areas, and there are people working to build towns and pave roads. Others are trying to establish an economic system for people to live securely and peacefully. And there's a judicial system that seeks to give people back their rights and not only to punish the wrongdoers in the way some people would think, when they hear it is an Islamic or a Salafi group.

Being strongly supportive of the four traditional Sunni madhahib (schools of jurisprudence), HTS has promoted and enforced the Shafi'i school in territories under its control, thereby gaining popular support and influence amongst the Shafi’i-majority population of Idlib. One objective of the promotion and implementation of the madh'hab system by HTS has been to foster institutionalisation of governance within the framework of traditional Islamic jurisprudence.[184] Scholar Abu Abdullah al-Shami, the chief of HTS's religious council, has stated that "relying on the schools of jurisprudence" is a pathway towards "getting closer to people". According to Bassam Sihiouni, an influential member of the High Council of the Fatwa:

"The schools of jurisprudence are among the safest ways of preserving a correct and inventive intellectual orientation while applying the laws, ethics and morals of Islam. On the contrary, abandoning these schools would result in a decline of jurisprudence on the basis of just and righteous thinking."[185]

Ines Barnard and Charlie Winter have described HTS as the "most complex and sophisticated Islamist group" in Syria, which integrates mobilisation of popular support and military operations through its strategic communication networks.[186] HTS has also expressed its support for the right of Palestinians to reclaim their land.[187]

In 2024, the BBC reported that the goal of HTS since its break with al-Qaeda has been limited to trying to establish Islamic rule in Syria rather than a wider caliphate. The report stated that the messaging of HTS after the fall of the Assad regime was "one of inclusiveness and a rejection of violence or revenge".[188] According to Iranian foreign minister Abbas Araghchi, HTS gave guarantees to protect Shia religious sites in Syria ahead of the fall of the Assad regime.[189]

Governance

Despite being a conservative Islamist political organization, HTS has not been socially draconian or extremist in its interpretation of Islamic governance. In contrast to organizations like the more hardline Taliban or extremist Islamic State, HTS has not imposed the harsher aspects and interpretations of Sharia over the populations of the regions it governs. Taxation in HTS-controlled areas has been minimized due to high poverty levels and fear of antagonizing locals to its rule. The organization has generally avoided interfering in the lives of women. It has not compelled the use hijabs/niqabs or discouraged women's access to education. In 2020, the organization allowed the formation of volunteer religious police but dismantled it within months, stating the concept had no place in a modern state. The organization has been quick to respond to pressure from the local population to change course on policy or rhetoric to avoid public backlashes. The generally lenient approach adopted by HTS was the result of years of internal restructuring within the organization that left the group with an uncontested leadership that had adopted a pragmatic outlook.[190]

HTS has largely refrained from controlling sectors of governance like education and health. After consolidating administrative control in Idlib, the organization allowed the preexisting Education Directorate to continue its operations. The curricula adopted in schools under HTS control are a mix of UNICEF and Syrian government textbooks (omitting glorification of the Ba'ath Party and the Al-Assad family).[191] Educational curricula of Tahrir al-Sham teach the Shafi'i schoo, the predominant madhab in Syria, and emphasize the importance of the four traditional schools of law in ensuring Muslim unity. In theology, Tahrir al-Sham officially follows the Athari school while also allowing Ash'arite scholarship in educational institutes and co-operating with mosques run by Ash'ari imamss. As it consolidated power over time, it also reduced its policy of moral policing, arguing that such duties were the role of "relevant ministries of the SSG".[192] Commenting on the changes since 2020, a female Islamist activist campaigning for women's issues stated:

Pressure on individual behaviour fell with the creation of HTS. Before, it would have been inconceivable to imagine that women could talk about politics like this. The pressure to wear the full veil (niqab) has also diminished... this situation is new. All the women wore the full veil after the liberation of Idlib. The current transformation exasperates religious hardliners, but more pressure cannot be exerted on society, or it might get out of control.[193]

Protection of minorities

For several years, HTS has worked to significantly improve relations with minority groups under its rule, such as the Syrian Christian and Druze communities of Idlib, notably returning property stolen during the civil war and permitting Christians in its territories to reopen churches.[194]

Following the fall of the Assad regime, HTS military commander Abu Hassan al-Hamawi met with Alawite leaders in Latakia to provide assurances that the minority group would not face retribution, pointing to the group's treatment of Christians in Aleppo as evidence of their commitment to protecting minorities. The group also announced a general amnesty for former regime soldiers, with exceptions for those who committed war crimes or participated in torture.[174]

In June 2022, HTS leader Abu Mohammad al-Julani met with a delegation of Druze leaders and inaugurated a project that facilitated water supply to the Druze-majority villages in the Harim Mountains. At the event, al-Julani assured the Druze leaders that he was committed to improving economic conditions in the region and expanding public services provided by the Syrian Salvation Government. Various Syrian observers viewed the event as part of a public outreach programme of HTS with local Druze residents.[195][196][197]

In 2022, Tahrir al-Sham permitted the re-opening of churches in Idlib, enabling the Christian residents to celebrate Mass. After a meeting with members of the Christian clergy and civil activists, al-Julani announced his policy to protect Christian participation in their religious rites and celebrations. He also promised the restoration of properties unjustly seized from Christian citizens. Al-Qaeda-aligned Hurras al-Din condemned the move, accusing the Salvation Government of changing Idlib to be "less Muslim". In response, Tahrir al-Sham leaders maintained that sharia (Islamic law) safeguarded the rights of non-Muslim citizens (dhimmi or musta'min) to observe and teach their religious rites within their communities, arguing for the need for tolerance and peaceful relations between religious communities living in an Islamic government.[198]

Hanna Celluf, Archpriest of a 1000-year-old church in Al-Quniyah and a member of the Franciscan Order, stated that Idlib residents have been free to practice their religious rites and expressed his pride in serving the Christians of Idlib.[199] In December 2024, following the swift overthrow of Assad, the group's spokesman, Hassan Abdel Ghani, stated that all religions will be free in the new Syrian state now that tyranny is gone forever.[200]

Structure

Member groups

The groups in italic are defectors from Ahrar al-Sham which either left to join Jabhat Fateh al-Sham in the last few days of its existence, or joined its successor group Tahrir al-Sham.

Following the fall of the Assad regime, HTS leadership announced plans to incorporate various militia groups into a unified national army under the ministry of defense, while pledging to exclude jihadist groups focused on attacking Western targets (such as ISIS). Military commander Abu Hassan al-Hamawi stated the unified force would be 'tasked with protecting the nation on behalf of all Syrians.'[174]

- Jabhat Fateh al-Sham

- Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar[201]

- Green Battalion

- Syrian Islamic Jihad Union (ex-Ansar Jihad)[202]

- Khorasan group

- Suqour al-Ezz

- Imam Bukhari Jamaat[203]

- Tawhid and Jihad Battalion ("Katibat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad")[204]

- Army of Muhammad

- Jamaat al-Murabitin[205]

- Supporters of Jihad[206]

- al-Ikhlas Brigade

- Mutah Brigade

- Ibn al-Qayyim Brigade

- al-Qaqa Islamic Brigade[207]

- Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar[201]

- Ansar al-Din Front

- Liwa al-Haqq[3]

- Jaysh al-Sunna (Idlib and Aleppo)[3]

- Mountain Lions Battalion[208]

- Knights of the Caliphate Battalion[209]

- Martyrs of Islam Front[210]

- Tawhid Battalion[211]

- Martyr Ibrahim Qabbani Battalion[212]

- Katibat Bayt al-Maqdis[213]

- Ansar al-Sham[214]

- Katibat al-Shahid Abu Usid.[215]

- Katibat Ashbal al-Sunnah[216]

- Kata'ib al-Sayf al-Umri[217]

- Jabhat al-Sadiqin[218]

- Liwa Ahl al-Sham[219]

- Lightning Battalion[220]

- Katibat al-Siddiq[221]

- Abu Talhah al-Ansari Battalion[222]

- 1st Regiment (Idlib)[223]

- Special Forces Brigade[224]

- Abu Amara Battalions (main unit)[118][117]

- Hani al-Nasr Brigade[226]

- Ajnad al-Sham (left in June 2017 to join Ahrar al-Sham, rejoined HTS in November 2017)[227]

- Jaysh Usrah[228]

- Imarat Kavkaz[229]

- Soldiers of the Epics[230]

- Army of Umar Ibn Khattab[231]

- Army of Aleppo

- Army of Eastern Ghouta

- Army of Abu Bakr as-Sadiq

- Army of Idlib

- Army of Al-Badia

- Army of Hama[226]

- Abdullah Azzam Brigade

- Usud al-Harb Brigade

- Ahl al-Bayt Brigade

- al-Majd Brigade

- Lions of Islam Brigade Artillery and Infantry Battalion (Junud al-Sham remnants)

- Army of Uthman Ibn Affan

- Army of Al-Sham

- Army of Al-Hudud

- Army of Al-Sahi

- al-Quds Brigades

- Glory of Islam Brigade

- al-Noor Islamic Movement

- Banners of Islam Movement

- Army of Al-Ghab Plain

- Army of Abu Bakr al-Siddiq

- Mountain Army

- Army of Omar bin al-Khattab

- Army of Othman bin Affan

- Aleppo City Battalion[232]

Leadership

Since October 2017, the "general commander" or emir of Tahrir al-Sham is Abu Mohammad al-Julani, who is also Tahrir al-Sham's "military commander" and the emir of Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, who also led its predecessor organisation al-Nusra Front, the Syrian branch of al-Qaeda until 2016.[233]

Previously, the general commander of Tahrir al-Sham was Hashim al-Shaykh, also known as Abu Jaber, who was the leader of Ahrar al-Sham between September 2014 and September 2015.[234] On 1 October 2017, Abu Jaber resigned from his position as the general leader of Tahrir al-Sham and was replaced by Abu Mohammad al-Julan. Abu Jaber took another position as the head of HTS's Shura council.[2]

Individuals in italic are defectors from Ahrar al-Sham, which either left to join Jabhat Fateh al-Sham in the last few days of its existence, or directly joined Tahrir al-Sham.

- Abu Jaber (emir, until October 2017)[3]

- Abu Mohammad al-Julani (overall military commander, later emir)

- Abu Hassan al-Hamwi (military wing commander, 2019–present)[173]

- Abu Khayr al-Masri † (senior leader)[235]

- Abu Maria al-Qahtani † (senior leader)

- Abu Ahmed Zakour (general financer, left group in 2023)

- Abu Salih Tahan (military commander)[236]

- Abu Badr al-Hijazi (military commander)[226]

- Abu Abdel Ghani al-Hamawi (administrator)

- Abu Mohammad al-Shari †[237]

- Abu Taher al-Hamawi (sheikh)[226]

Former groups

- Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement

- Ibn Taymiyyah Battalions (joined Ahrar al-Sham)[139]

- Jaysh al-Ahrar[238]

- Harakat Fajr ash-Sham al-Islamiya (became Ansar al-Din Front – Harakat Fajr ash-Sham al-Islamiya)[65]

- al-Murabitin Battalion

- Osama Battalion

- Abu Ali Yemeni Battalion

- Abu Hilal Zitan Battalion

- Former HTS groups that went to join the Guardians of Religion Organization[239]

- Jaysh al-Badia

- Jaysh al-Malahim

- Jaysh al-Sahil

- Saraya al-Sahil

- Jund al-Sharia

- Siriyatan Kabil

Former leaders

- Tawfiq Shahabuddin (sheikh of the Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement, which left HTS in July 2017)[6]

- Abdullah al-Muhaysini (sheikh, left in September 2017)[240]

Political relations

Al-Qaeda

Initial Disputes (2017–2019)

During its foundation declaration, the first Emir Abu Jaber Shaykh had described the Levant Liberation Committee as "an independent entity" free from all the previous relations and allegiances as a result of the newly formed union with various Syrian Islamic militias, thereby disassociating itself from previously dissolved factions such as the Al-Nusra Front.[241] Since officially disassociating from Al-Qaeda in 2017, Tahrir al-Sham has formally established governance over many parts of North-West Syria.[242]

In November 2017, HTS launched a wide-scale crackdown on Al-Qaeda elements in Idlib and arrested prominent leaders from Af-Pak region and Al-Nusra Front such as Sami al-Oraydi. Emir Ayman al-Zawahiri opposed the split of HTS from Al-Qaeda, stating that it was a treasonous act done without his consent and further denounced the clampdown on foreign Jihadist fighters through an audio-statement.[243] Several Al-Qaeda circles and supporters have also condemned Joulani and compared him to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi because of the group's conflicts with other rebel groups, and have described him as an 'opportunist' as well as making claims that he is an agent of foreign powers.[244]

Conflict (since 2020)

After reaching a ceasefire deal brokered by Turkey, HTS turned its attention to destroying Al-Qaeda cells and Islamic State remnants in Idlib.[166] Rivalry between Al-Qaeda aligned Hurras al-Din and Tahrir al-Sham had begun to escalate violently as early as December 2019. In February 2021, HTS intensified its fight against al-Qaeda cells by launching a large-scale crackdown that saw many military commanders and leaders of Hurras al-Din incarcerated.[160] According to Istanbul-based academic Abbas Sharifeh, the measures were part of a strategy by HTS for governance consolidation: "Golani simply does not want any competitors in Idlib, especially from a jihadi current affiliated with al-Qaeda."[160] By 2023 Tahrir al-Sham had eliminated most of the clandestine networks of Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, disarmed the militias and established total control over Idlib.[166]

In 2019, U.S. government alleged that Tahrir al-Sham was working with al-Qaeda's Syrian branch on a covert level, despite its self-identification as a distinct organisation.[245] Some analysts assert that many of the group's senior figures, particularly Abu Jaber, held similarly extreme views.[181][61] However, Tahrir al-Sham has officially denied being part of al-Qaeda and said in a statement that the group is "an independent entity and not an extension of previous organizations or factions".[1] In his 2021 interview to PBS News, Abu Muhammad al-Julani argued that financial co-operation with Al-Qaeda was necessary to defend Syrians from the tyranny of the Assad regime, and stated that "even at that time when we were with Al Qaeda, we were against external attacks".[183] Clarifying the reasons behind the termination of relations with Al-Qaeda, Julani said:

"[W]hen we saw that the interest of the revolution and the interest of the people of Syria was also to break up from [the] Al Qaeda organization, we initiated this ourselves without pressure from anybody, without anybody talking to us about it or requesting anything. It was an individual, personal initiative based on what we thought was in the public interest that benefits the Syrian revolution."[183]

Ahrar al-Sham

According to Abdul Razzaq al-Mahdi, who was a leading scholar in Tahrir al-Sham, the groups do not particularly hate one another in the political or social battlefield. Certain members, however, do believe that a war between the two would be possible, since Ahrar al-Sham's attendance at the Astana talks labels it as a "moderate" faction, often seen as blasphemy within groups such as Tahrir al-Sham.[246]

In February 2018 Ahrar al-Sham and the Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement merged and formed the Syrian Liberation Front then launched an offensive against Tahrir al-Sham seizing several villages and the city of Maarrat al-Nu'man.[citation needed]

Designation as a terrorist organization and sanctions

| Country | Date | References |

|---|---|---|

| 31 May 2018 | [57] | |

| 23 May 2018 | [48] | |

| 31 August 2018 | [247] | |

| May 2017 | [248][249] | |

| 4 June 2020; the decision came into force on 20 July 2020 |

[250] | |

| 14 April 2014 (Labelled as an alias of Al-Nusra Front)[46] |

[46] | |

| 14 April 2014 (Labelled as an alias of Al-Nusra Front[52]) |

[52] | |

| 9 April 2022 | [251] | |

| 7 November 2013 (Originally labelled as Al-Nusra) |

[252] | |

| 14 May 2014 (Labelled as an alias of Al-Nusra Front[51]) |

[51] | |

| 21 October 2024 (Previously labelled as Al-Nusra Front since 2016, added as an alias of Al-Nusra Front since 21 October 2024) |

[253] | |

| [254] | ||

| September 2020 | [255] |

HTS is designated a terrorist group by the United States, European Union, Russia, United Kingdom, Canada, and some other countries.[256] The US embassy in Syria, which had suspended operations in February 2012, confirmed in May 2017 that HTS had been designated a terrorist organization in March 2017. A US State Department spokesperson further stated that a review of HTS's internal mechanisms was being conducted to analyse "the issue carefully".[257] In May 2018, the United States Department of State formally added HTS to its list of "Foreign Terrorist Organizations" (FTO).[57][242] The United States officially confirmed in June 2023 that HTS leader Joulani had severed links to Al-Qaeda in 2016, while sanctioning individuals known to finance HTS. These included Abu Ahmed Zakour, a member of HTS's Majlis ash-Shura.[258]

Canada designated Tahrir al-Sham as a terrorist organization on 23 May 2018.[48]

In August 2018, Turkey designated Tahrir al-Sham as a terrorist organization.[259] Despite this, the Turkish army has pursued strategic co-operation with HTS, viewing them as allies in the fight against Al-Qaeda and Islamic State remnants. Since the objective of Tahrir al-Sham was defending Idlib from the Baathist regime and consolidating governance, it became a party to several ceasefire agreements brokered by Turkey. Following the ceasefire deal in March 2020, HTS turned its focus to eradicating independent militias and hardline Jihadist factions in Idlib. Within a few weeks it was able to dismantle all the Al-Qaeda networks and eventually succeeded in achieving undisputed control of Idlib by subduing or co-opting other rebel factions.[166]

Following the fall of the Assad regime during the 2024 Syrian opposition offensives spearheaded by Tahrir al-Sham, the BBC News reported that the UK government could remove HTS from its list of terrorist groups.[260] This was echoed by Geir Otto Pedersen, the UN special envoy for Syria, who told Financial Times that international powers would need to consider lifting the designation.[261]

Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan stated that HTS should be removed from the list of terrorist organizations and called on Western states.[262][263] A few days after this statement, Fidan went to Damascus and met with HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa. Thus, Fidan became the first foreign minister to visit the transitional government established by HTS.[264][265]

On 17 December 2024, the leader of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, called for the Russian government to remove the HTS from Moscow's list of banned terror groups.[266]

On 20 December 2024, the United States lifted a $10-million reward it placed for the arrest of Sharaa following meetings between HTS officials and US diplomats in Damascus.[267]

HTS response

In response to the American designation of HTS as a terrorist organisation; Abu Muhammad al-Julani, distancing himself from past involvement with Al-Qaeda, stated in a 2021 interview to PBS Frontline:

Our message to them is brief. We here do not pose any threat to you, so there is no need for you to classify people as terrorists and announce rewards for killing them. And also, all that does not affect the Syrian revolution negatively. This is the most important message. The second message is that the American policies in the region, and in Syria in particular, are incorrect policies that require huge amendments... What we might have in common would be putting an end to the humanitarian crisis and suffering that is going on in the region, and putting an end to the masses of refugees that flee to Turkey or to Europe and create huge issues, either for the Syrian people, who are being displaced all over Europe, or for the Europeans themselves.. This is the issue that we can cooperate the most on, by helping people stay here, by providing them with a dignified life here, in the region, or by liberating the lands of these people so that they can return to their homes, instead of having Russia or the Iranian militias push them to flee abroad.[183][268]

Foreign support

Turkey

In 2018, Turkey designated Tahrir al-Sham as a terrorist organization and the Al-Nusra Front in 2014. The Turkish government said it was opposed to Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), and had fought with it and declared it a terrorist organisation, and HTS's Syrian Salvation Government was a direct challenge to the Turkish-backed Syrian Interim Government.[269]

However, since 2017 there have been times where HTS, particularly its pragmatic faction around Abu Muhammed al-Julani, has fought alongside the Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army. HTS has not stopped Turkey from setting up several observation posts in Idlib and has joined joint operations rooms with Turkish-backed groups while preserving its autonomy. The Clingendael Institute in November 2019 has described the Turkish policy since 2018 as attempting to divide the pragmatic elements from the hardline elements within HTS.[269]

The head of the Turkish intelligence agency MIT, İbrahim Kalın, visited Damascus on December 12 and met with Ahmed al-Sharaa, the leader of HTS. Kalın's visit was the first by a senior foreign official in Damascus since rebels take over.[270][271][272] Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan stated in an interview after the fall of the Assad regime that Turkey cooperated with HTS during his time as the head of the Turkish intelligence agency MIT and that HTS provided Turkey with information on many members of ISIS and Al Qaeda, including high-ranking officials.[273][274]

Human rights violations and war crimes

Despite HTS's efforts to publicly distance itself from al-Qaeda and present itself as a legitimate governing body through the Syrian Salvation Government, reports from the United Nations, United States, European Union and human rights organizations document its continued involvement in serious human rights violations and war crimes.[275][276][277][278][279]

Extrajudicial executions, arbitrary arrests, and torture

HTS carries out extrajudicial killings, arbitrary arrests, and forced disappearances.[275][280] Political opponents, journalists, activists, and civilians perceived as critical of HTS are unlawfully detained.[280] Torture and mistreatment are widespread in detention facilities operated by HTS, with at least 22 documented methods of torture being employed by HTS, including physical and psychological abuse.[281] Confessions obtained under torture are admitted as evidence in HTS courts, while detainees have no legal recourse to challenge their imprisonment.[275][281][278] In 2019 a Human Rights Watch report accused the group of torturing locals who were documenting their abuses in areas they controlled.[282]

Violence against women and girls

HTS enforces strict, religiously motivated dress codes for women and girls, and significantly restricts their freedom of movement and access to education. Women are only allowed to travel when accompanied by a male relative (mahram), with violations of religious decrees possibly leading to arrest and punishment.[275][281] A U.S. State Department report in 2023 asserted that women in HTS-controlled regions of Idlib faced widespread discrimination and violence, including arbitrary detention, sexual abuse in custody, and death sentences for charges such as "adultery" or "blasphemy".[275] It also alleged that women were also denied the right to file for divorce and are forbidden from wearing makeup in public and living alone.[275] US government agency USCIRF alleged in 2022 that the education ministry of the Syrian Salvation Government gave instructions to block married female students – including underage girls who were forced into child marriage – from attending public schools and universities.[279]

Women activists, especially those working in humanitarian or media roles, have been particularly targeted.[275][277] Many are accused of high treason or other charges as a pretext to pressure them into ceasing activities critical of HTS.[277] HTS has also arrested women with family ties to rival groups or opposition factions as a tactic to extract leverage or force cooperation.[277] Female detainees are subjected to degrading conditions, including isolation, threats, lack of medical care, and abuse.[275][277]

Allegations of forced conversions and discrimination against religious minorities

A 2022 report issued by the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) alleged that while HTS publicly claimed to be tolerant and made official overtures towards religious minorities in Idlib like Druze and Christians, it continued to commit widespread violations of religious freedom and human rights, targeting religious minorities and dissenting Sunni Muslims. According to the USCIRF report, the group forcibly converted Druze to Sunni Islam and that properties of Christians and Druze were systematically confiscated in HTS-controlled territories. Arbitrary arrests, torture, and executions under fabricated religious charges are routine in HTS-controlled territories, with detainees often subjected to abuse and denied legal recourse. The USCIRF concludes that HTS promotes an ideologically driven administration that undermines the region's religious diversity.[279]

Political repression

HTS systematically suppresses dissent through violent repression, arbitrary arrests and severe mistreatment of critics, including journalists, activists, and civilians.[275][280][278] Protests against HTS are rarely tolerated and often met with violent repression.[275][278] Journalists face significant risks, including threats, imprisonment, and physical abuse, forcing many to flee the region.[275] HTS employs arbitrary detentions and torture to silence perceived political opponents.[275][280][278]

Obstruction of humanitarian aid

According to a report issued by US State Department in 2023, HTS significantly obstructed humanitarian aid in areas under its control, severely hindering assistance to those in need, particularly internally displaced persons.[275] The group imposes arbitrary taxes on humanitarian shipments and interferes with the distribution of aid.[275] HTS regulates the flow of assistance, exerting control over the selection of beneficiaries and ensuring that aid is diverted for its own benefit.[275]

Children as victims and forced participants of war

According to reports by the U.S. Department of State, HTS has committed severe violations of children's rights, exploiting them in ways that contravene international law. These reports alleged that HTS used children as human shields, suicide bombers, child soldiers, and executioners, forcing them into violent roles in the conflict.[276][283][284]

See also

- Army of Conquest

- Inter-rebel conflict during the Syrian Civil War

- List of armed groups in the Syrian Civil War

- List of terrorist incidents in Syria

- National Front for Liberation–Tahrir al-Sham conflict

- Northwestern Syria offensive (April–June 2015)

- Second Battle of Idlib

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d Joscelyn, Thomas (10 February 2017). "Hay'at Tahrir al Sham leader calls for 'unity' in Syrian insurgency". Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b c "Julani is a temporary leader of the 'Liberation of the Sham' ... This is the fate of its former leader". HuffPost. 2 October 2017. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Joscelyn, Thomas (28 January 2017). "Al Qaeda and allies announce 'new entity' in Syria". Long War Journal. Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Christou, William (13 December 2024). "Syrian rebels reveal year-long plot that brought down Assad regime". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "A prominent Tahrir al-Sham commander killed in southern Idlib". Islamic World News. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Nour e-Din a-Zinki defects from HTS, citing unwillingness to end rebel infighting". Syria Direct. 20 July 2017. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ a b Grant-Brook, William (2023). "Documenting life amidst the Syrian war: Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham's performance of statehood through identity documents". Citizenship Studies. 27 (7): 855, 856. doi:10.1080/13621025.2024.2321718.

- ^ a b Drevon, Haenni; Jerome, Patrick (2021). How Global Jihad Relocalises and Where it Leads: The Case of HTS, the Former AQ Franchise in Syria. San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy: European University Institute: European University Institute. pp. i, 8, 28–29. ISSN 1028-3625.

- ^ a b Drevon, Jerome (2024). From Jihad to Politics: How Syrian Jihadis Embraced Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 2, 132. ISBN 9780197765166. LCCN 2024012918.

- ^ Zelin, Aaron Y. (2022). "2: The Development of Political Jihadism". The Age of Political Jihadism: A Study of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. Washington, DC: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. pp. 34, 35. ISBN 979-8-9854474-4-6.

- ^ "Affiliation with Tahrir Al-Sham; Reasons and Motives II". MENA. 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Tammy, Lynn Palacios. "Hayat Tahrir al-Sham's Top-Down Disassociation from al-Qaeda in Syria". Jamestown. The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Pierre, Boussel. "The new age of armed groups in the Middle East". Foundation for Strategic Research. Archived from the original on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

Jurists who support the Salafist cause and personalities from civil society constitute a minority.

- ^ Drevon, Haenni; Jerome, Patrick (2021). How Global Jihad Relocalises and Where it Leads: The Case of HTS, the Former AQ Franchise in Syria. San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy: European University Institute: European University Institute. p. 20. ISSN 1028-3625.

- ^ Drevon, Haenni; Jerome, Patrick (2021). "Abstract". How Global Jihad Relocalises and Where it Leads: The Case of HTS, the Former AQ Franchise in Syria (PDF). San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy: European University Institute. p. v. ISSN 1028-3625. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

HTS's domination was followed by a policy of gradual opening and mainstreamisation. The group has had to open up to local communities and make concessions, especially in the religious sphere. HTS is seeking international acceptance with the development of a strategic partnership with Turkey and desires to open dialogue with Western countries. Overall, HTS has transformed from formerly being a salafi jihadi organisation into having a new mainstream approach to political Islam.

- ^ Grant-Brook, William (2023). "The State in Idlib: Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham and Complexity Amid the Syrian Civil War". In Fraihat, Alijla; Ibrahim, Abdalhadi (eds.). Rebel Governance in the Middle East. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 78. ISBN 978-981-99-1334-3.

Over the decade of Syria's conflict, HTS has morphed from an al-Qa'ida affiliated transnational jihadist group that was one of many opposition units to a locally rooted, conservative Islamist movement that is the de facto state power in one corner of the country.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Grant-Brook, William (2023). "Documenting life amidst the Syrian war: Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham's performance of statehood through identity documents". Citizenship Studies. 27 (7): 855. doi:10.1080/13621025.2024.2321718.

The issuance and distribution of legal identity documen-tation is central to the group's efforts to organise and regulate Idlib and surrounding areas. ... It also exemplifies the group's shift from transnational jihad to a conservative, locally rooted Islamist nationalist defacto government.

- Drevon, Jerome (2024). From Jihad to Politics: How Syrian Jihadis Embraced Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 3, 196, 197, 203–206. ISBN 9780197765166. LCCN 2024012918.

- Grant-Brook, William (2023). "Documenting life amidst the Syrian war: Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham's performance of statehood through identity documents". Citizenship Studies. 27 (7): 855. doi:10.1080/13621025.2024.2321718.

- ^ a b Rida, Nazeer (30 January 2017). "Syria: Surfacing of 'Hai'at Tahrir al-Sham' Threatens Truce". Asharq Al-Awsat. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- ^ Reality Check team (22 June 2019). "Syria: Who's in control of Idlib?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ Macaron, Joe (17 October 2018). "A confrontation in Idlib remains inevitable". Al-Jazeera. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ Ali, Zulfiqar (18 February 2020). "Syria: Who's in control of Idlib?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ a b Chair of the Security Council Committee (3 February 2022). "Letter ... pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da'esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities" (PDF). Letter to President of the Security Council. United Nations Security Council.

- ^

- Burke, Jason (11 December 2024). "Islamist groups from across the world congratulate HTS on victory in Syria". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 January 2025.

- "The Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, held a telephonic conversation with the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Syrian Interim Government". mfa.gov.af. December 2024. Archived from the original on 28 December 2024.

- Amini, Shujauddin (28 December 2024). "Taliban Appeal to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham for Presence in Syria". 8AM Media. Archived from the original on 31 December 2024.

- ^

- Fraihat, Alijla; Ibrahim, Abdalhadi; Grant-Brook, William (2023). "The State in Idlib: Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham and Complexity Amid the Syrian Civil War". Rebel Governance in the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 76. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-1335-0. ISBN 978-981-99-1334-3. S2CID 264040574.

HTS's most important foreign relationship at present is with Ankara. HTS has a close relationship with its northern neighbour, allowing Turkish soldiers' presence in Idlib to uphold an unstable stalemate with Assad's forces.

- Hamming, Tore (2022). Jihadi Politics: The Global Jihadi Civil War, 2014–2019. London, UK: Hurst. pp. 48, 396. ISBN 9781787387027.

Ahrar al-Sham (and later HTS) established close relations with Turkey. ... In Syria, Turkey managed to establish close relations first with Ahrar al-Sham and subsequently with HTS.

- Iddon, Paul (5 April 2021). "Are Turkey and the Islamist HTS group in Syria's Idlib allies?". ahvalnews.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2023.

- "Containing Transnational Jihadists in Syria's North West". International Crisis Group. 7 March 2023. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023.

HTS declared that only it or al-Fatah al-Mubin, which it leads together with Turkish-backed factions (though it is the dominant force), could conduct military operations in Idlib.

- Fraihat, Alijla; Ibrahim, Abdalhadi; Grant-Brook, William (2023). "The State in Idlib: Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham and Complexity Amid the Syrian Civil War". Rebel Governance in the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 76. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-1335-0. ISBN 978-981-99-1334-3. S2CID 264040574.

- ^ Soylu, Ragip (2 December 2024). "Has Ukraine helped the Syrian rebel offensive in Aleppo?". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 2 December 2024.

- ^ "Ukrainian intelligence coordinating with Syrian rebels against 'mutual enemy', says opposition figure". The New Arab. 4 December 2024. Archived from the original on 4 December 2024.

- ^ Sosnowski, Marika (2023). Redefining Ceasefires: Wartime Order and Statebuilding in Syria. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-009-34722-8.

- ^ Obaid, Nawaf (15 August 2018). "Trump Will Regret Changing His Mind About Qatar". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ Drevon, Haenni; Jeromev, Patrick (2021). How Global Jihad Relocalises and Where it Leads: The Case of HTS, the Former AQ Franchise in Syria. San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy: European University Institute. pp. 18, 29–31. ISSN 1028-3625.

- ^ Zelin, Aaron Y. (2022). "2: The Development of Political Jihadism". The Age of Political Jihadism: A Study of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. Washington DC, USA: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. p. 11. ISBN 979-8-9854474-4-6.

- ^ "Tarkhan's Jamaat (Katiba İbad ar-Rahman) Fighting In Hama Alongside Muslim Shishani". Chechens in Syria. 29 January 2018. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Борбор азиялык жихадчылар "Аль-Каидага" ант беришти [Central Asian jihadists pledge allegiance to Al-Qaeda]. BBC News (in Kyrgyz). Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ Al-Tamimi, Aymenn Jawad. "The Factions of North Latakia". Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "More Detailed Information & Interview With Newly-Formed Tatar Group Junud Al-Makhdi Whose Amir Trained In North Caucasus With Khattab". Chechens in Syria. 3 July 2016. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ "Foreign jihadists advertise role in Latakia fighting". The Long War Journal. 11 July 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ "Malhama Tactical, The Fanatics Tactical Guru!". The Firearm Blog. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Weiss, Caleb (18 January 2018). "New Uighur jihadist group emerges in Syria". Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ "Turkey-backed fighters join forces with HTS rebels in Idlib". Al Jazeera. 10 July 2020. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ Blomfield, Adrian (18 December 2024). "US 'prepared Syrian rebel group to help topple Bashar al-Assad'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 December 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ هجوم مباغت لهيئة تحرير الشام في ريف حلب يسفر عن مقتل 10 عناصر من ميليشيا النجباء العراقية [A surprise attack by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham in the Aleppo countryside results in the killing of 10 members of the Iraqi al-Nujaba militia]. 12 September 2017. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Idlib Faces a Fearsome Future: Islamist Rule or Mass Murder". 19 September 2019. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "Syria war: 'Dozens killed' as jihadists clash in Idlib". BBC News. 14 February 2017. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ a b Mroue, Bassem (14 February 2017). "Clashes between 2 extremist groups kill scores in Syria". Associated Press. Beirut. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ Lund, Aron (23 February 2018). "Understanding Eastern Ghouta in Syria". New Humanitarian. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "تحرير الشام" تدُكّ مواقع النظام شمال حمص.. وتُكبِّده خسائر (صور) [Tahrir al-Sham bombs regime positions north of Homs, inflicting heavy losses (photos)]. El-Dorar al-Shamia. 17 April 2018. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Justicia, Ministerio de. "Entidades" [Entities]. repet.jus.gob.ar (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ "Listed terrorist organisations". Australian National Security. Archived from the original on 25 October 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada (30 May 2018). "Canada Gazette, Part 2, Volume 152, Number 11: Regulations Amending the Regulations Establishing a List of Entities". gazette.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ^ "1.3. Anti-government armed groups". European Union Agency for Asylum. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Detachment 88 (21 October 2024). "Daftar terduga teroris dan organisasi teroris no. DTTOT/P-18a/50/X/RES.6.1./2024" (PDF). Pusat Pelaporan dan Analisis Transaksi Keuangan. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "International Terrorists notified pursuant to Section 3 of the International Terrorist Property Freezing Act" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Lists associated with Resolutions 1267/1989/2253 and 1988". New Zealand Police. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ Единый федеральный список организаций, в том числе иностранных и международных организаций, признанных в соответствии с законодательством Российской Федерации террористическими [Unified federal list of organizations, including foreign and international organizations, recognized in accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation as terrorist]. www.fsb.ru. Federal Security Service. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ "Turkey designates Syria's Tahrir al-Sham as terrorist group". Reuters. 31 August 2018. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Proscribed terrorist groups or organisations". Home Office. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "The Proscribed Organisations (Name Change) Order 2017: Article 2", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 2017/615 (art. 2)

- ^ a b c "Amendments to the Terrorist Designations of al-Nusrah Front". Office of the Spokesperson. U.S. Department of State. 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021.

- ^ "Briefing Security Council on Syria, Senior Official Urges All Parties De-escalate Military Situation in Country, Region, Prioritize Protection of Civilians Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". United Nations. Archived from the original on 26 November 2024. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ Drevon, Haenni; Jerome, Patrick (2021). "Abstract". How Global Jihad Relocalises and Where it Leads: The Case of HTS, the Former AQ Franchise in Syria (PDF). San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy: European University Institute. p. v. ISSN 1028-3625. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

HTS's domination was followed by a policy of gradual opening and mainstreamisation. The group has had to open up to local communities and make concessions, especially in the religious sphere. HTS is seeking international acceptance with the development of a strategic partnership with Turkey and desires to open dialogue with Western countries. Overall, HTS has transformed from formerly being a salafi jihadi organisation into having a new mainstream approach to political Islam.

- ^ Zelin, Aaron Y. (2022). "2: The Development of Political Jihadism". The Age of Political Jihadism: A Study of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. Washington, DC: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. pp. 7–12. ISBN 979-8-9854474-4-6.

- ^ a b "Tahrir al-Sham: Al-Qaeda's latest incarnation in Syria". BBC News. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ a b Alami, Mona (6 December 2017). "Syria's Largest Militant Alliance Steps Further Away From Al-Qaeda". Syria Deply. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Joscelyn, Thomas (10 February 2017). "Hay'at Tahrir al Sham leader calls for 'unity' in Syrian insurgency". Long Wars Journal. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017.

- ^ "Syria Islamist factions, including former al Qaeda branch, join forces: statement". Reuters. 28 January 2017. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ^ a b "New component split from 'Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham'". Syria Call. 9 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Tsurkov, Elizabeth (10 November 2020). "Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (Syria)". European Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020.

- ^ "The Syrian General Conference Faces the Interim Government in Idlib". Enab Baladi. 18 September 2017. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Syria news". Shaam network- www.shaam.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Drevon, Haenni; Jerome, Patrick (2021). "II: The Political Deprogramming of the Radical Emirate". How Global Jihad Relocalises and Where it Leads: The Case of HTS, the Former AQ Franchise in Syria. San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy: European University Institute: European University Institute. pp. 12–20. ISSN 1028-3625.

- ^ a b "Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023.

- ^ Lennon, Connor (12 December 2024). "The de facto authority in Syria is a designated terrorist group: What happens now?". UN News. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "Syria's Islamist rebel leader holds meeting in Damascus with visiting UN envoy". South China Morning Post. 16 December 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b c "Who is Abu Mohammed al-Julani, leader of HTS in Syria?". Al Jazeera. 4 December 2024. Archived from the original on 8 December 2024.

- ^ a b Raya Jalabi (7 December 2024). "Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, the Syrian rebel leader hoping to overthrow Assad". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Everything You Need to Know About the New Nusra Front". 28 July 2016.

- ^ a b Atassi, Basma (9 June 2013). "Qaeda chief annuls Syrian-Iraqi jihad merger". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020.

- ^ a b Lund, Aron (3 February 2014). "A Public Service Announcement From Al-Qaeda". Carnegie Middle East Center. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ^ Bunzel, Cole (5 October 2013). "al-Baghdadi Triumphant". Jihadica. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013.

- ^ Perkoski, Evan (2022). "5: Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State". Divided, Not Conquered: How Rebels Fracture and Splinters Behave. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 168, 169. ISBN 9780197627075.

- ^ "Jihadists advance on Syria's Raqqa". NOW. 10 January 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Yacoub Oweis, Khaled (13 January 2014). "Group linked to al-Qaeda regains ground in northeast Syria". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016.

- ^ Perkoski, Evan (2022). "5: Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State". Divided, Not Conquered: How Rebels Fracture and Splinters Behave. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780197627075.

- ^ "Al-Qaeda disavows any ties with radical Islamist ISIS group in Syria, Iraq - the Washington Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2024.