Talk:Blackfriars, Leicester

Discussion page of the Article on Leicester Blackfriars

John Nichols Source

[edit]JOHN NICHOLS. HISTORY & ANTIQUITIES OF LEICESTERSHIRE. VOLUME 1.2 (1815). PAGE 295-6, ON THE DOMINICANS OR BLACKFRIARS.[1]

[edit](Page 295)

On the Dominicans or Blackfriars

The Mendicant Friars, it may be proper to observe, were divided into four distinct orders; which according to Mosheim, were thus classed; the Dominicans, Franciscans, Carmelites, and Hermits of St. Augustine. And the same learned writer observes that

“The enthusiastic attachment to these sanctimonious beggars went so far, that, as we learn from the most authentic records, several cities were divided or cantoned out into four parts, with a view to these four orders; the first part being assigned to the Dominicans; the second to the Franciscans; the third to the Carmelites; and the fourth to the Augustinians.”

The Order of Friars Preachers, or Blackfriars, was begun in the Pontificate of Innocent III, by St. Dominic, who bring at first a canon, with a few who chose to be his companions, instituted a new rule of strict holy living; and, lest they should grow sluggish in the service of God by staying at home, he appointed them, in imitation of Christ our blessed Saviour, to travel far and wide to preach the holy Gospel; which order Honorius III confirmed; and Gregory IX canonised their founder. They were called Dominicans from the founder; Preaching Friars from their office to preach; and Black Friars from their garments. Their first habit was the same as that of the Austin Canons; and they followed the same rule; but they soon changed their dress, and had a long white tunic with and a white hood over it; and when they went abroad, a black cloak with a black hood over their vestments. They came to England in 1217.

Friaries were seldom endowed, the friars being by their profession mendicants, and to have no property. Yet many of them were large and stately buildings, in which many great persons chose to be buried. The site of those in Leicester is well known; but there has been no tradition for a long time to distinguish precisely their different orders. Hence in the plan drawn up by Mr Thomas Roberts (which for the part of a surveyor is very exact), we find near the Northgate the White Friars in Leicester; and others are misplaced.

The Church of the Dominicans, or Friars Preachers, commonly called Black Friars of St Clement’s, or Le Blak Frears in le Ashes, was founded by Simon de Montfort the second Earl of Leicester of that name; and was dedicated to St Clement. The Matriculus of 1220 informs us that the vicarage of St. Clement’s was then so poor that it was scarcely sufficient to maintain a Chaplain; and therefore it is likely that the church was providently given to these Friars Preachers to officiate in; and Mr Carte supposed “in le Ashes” related to the many ash-trees which of old grew in their precincts, and that they had the title St Clement because they were situated in that parish. It appears from some old writings that a land from the North Gate turning westward to the Friars adjoining, then southward between the said friars and the houses opposite All Saints Church, is called St. Clement’s lane; and therefore it is probable that the church was situated in or near it; and that upon its being demolished the parish was united to St. Nicholas or All Saints, or partly to the one, and partly to the other. The Matriculos of 1220 tells that it was scarcely sufficient to maintain a chaplain.

In Mr. Le Neve’s Register relating to the church in Lichfield, there is a delegation to the guardians of the Friars Preachers and the Friars Minor at Leicester, to hear and determine a difference about tithes (at Bakewell, it is believed, in Derbyshire) between the dean and chapter of Lichfield and the prior and convent of Lenton in Nottinghamshire, from Pope Innocent IV. anno pont X; and the guardian of the Friars Minors finished the same “die Sabbati poft Purificationem Ste Marie, 1252.”

In 1285, Robert Willoughby and Alice his wife were benefactors to the Dominican Priory at Leicester.

“Juratores dicunt, quod non est ad dampnum dni regis nec aliorum, licet dnus rex concedat Roberto de Willoughby and Alicie uxori ejus quod dant fratribus predicatoribus ville Leicestrie duas placeas in eadum villa; & quod predicte placee terre tenentur de domino Edwardo comite Leic’, per servitium IXd. per annum, & continet in longitudine CIII pedes, est in latitudine LXXX.”

In 1321, Thomas Earl of Lancaster and Leicester was also a benefactor.

In 1337 and 1345, the possessions of this priory were confirmed by the letters patent of King Edward III.

In 1357, Henry Duke of Lancaster, Earl of Derby, Earl of Lincoln and Earl of Leicester l, granted to the Friars Prea-

(Page 296)

chers of Leicester liberty to fish three days weekly (Wednesdays, Tuesdays, and Saturdays) in the river Soar, with a net of convenient mesh, so as not to destroy the young fish:

“As touz ceux qe cestes tres verront ou orront, Henri duc de Lancastre, cont de Derby, de Nicole, & de Leicestre, & seneschal d’Engleterre, falute en Dieu. Sachez nous de ñre grace especiall avoir done conge a nos clis en Dieu le prior & le convent de Frers Precheus de Leicestre, qu’ils puissent chescone sygmaigne trois jours, c’est assavoir, Mykerdy, Vendredy, & Samedy, pecher ove une fluv de convenable mesh sanz destruction de ticoyn pesceon, & meanment pvable de resone, en la ryvere de Sore desouz lour clos, & issuñ qu’ils peschent de jour, & nemye de noct. En tesmoignage de quele chofe, nos avons fait faire cestes noz lres patentes, enseallez de ñre seal, & doñ a ñre chastel de Leicestre, le darrein jour de Fevrier, & l’an du regne ñre seigneur le roi Edward Tiers puis le Conquest trentisme.”

William Layton was prior of this convent in 1505. To him and his successors the Corporation of Leicester, by Act of Common Hall, September 21, 1505, granted the pasture of two cows in their common pasture called the Cow hay; for which the prior paid 20 marks and engaged that his house should pray for them forever. In 1531, the Wardens of the Company of Shoe Makers agreed to pay them yearly ten marks, over and above the usual offering duties, to have their prayers.

Ralph Burrell, the last prior, surrendered this convent on the 10th of November 1539.

“Omnibus Christi fidelibus, &c. Frater Radus Burrell O.P. prior domus sive prioratus Sancti Clementi de Leycester, Ordinis Sancti Dominici, vaulgariter nunciapat’ ‘Le Blak Frears in le Ashes’, in com. Leycester, alias dictus frater Radus Burrell O.P. prior domus sive prioratus Fratrum Predicantum vaulgariter nunciapat’ le Blakfreears de Leycester, in com’ Leic’, & ejusdem loci conventus, &c. Nov 10, anno regni 30. * Per me Radm Burrell O.P. Priorem, ac Doctorum fac Theologie * Per me Will’m Hopkyn O.P. Sub-Priorem. * Per me Johannem Harford O.P. * Per me Ricardum Yngylby O.P. * Per me Elizeum Jem O.P. * Per me Johannem Hern O.P. * Per me Johannem Kok O.P. * Per me Ricum Blasvyn O.P. * Per me Edwardum Whornarek O.P. * Per me Robertum Sutton O.P.

The ministers accompts in the Augmentation-office thus describe the lands and possessions of the late house of Dominican Friars (fratrum Dominicalium) in the town of Leicester.

“The account of Thomas Catelyn, gent. Collector of the rents thereof. He answers for £2 for a house within the precinct of the late house of friars afforesaid, called Robert Orton’s House, with the appurtenances, together with the gardens and the closes, and also with a grove of willows near the Soar, and also with the churchyard there, in the tenure of William Lenbridge; as also the herbage of all lands within the limits and precincts of said house; demised to Thomas Catlyn, gent. by indenture under the common seal of the late house, dated 10th or September 30 Henry VIII exemplified by decree of the Court of Augmentations, under the decree of the chancellor and council of that court; to have and to hold, to the said Thomas Catlyn and his assigns, from the day of the date of the indenture, for fifty years, at the rent of 40 shillings at Lady Day and Michaelmas; with a covenant that the lessee shall have ‘Hedgboote, Lope, Tope, Croppe,’ or all manner, woods and under woods. The lessee to be charged with all repairs, ‘exceptis lapidibus, maeremio, fundulis, & clavis.” The site of the late house aforesaid He answers also for 20d. for rent of the Cloisteryard, with the residue of the ground and land most apt for tenements, within the precincts of the said house, reserved in the hands of the prior and convent. Sum total, — £2. 1s. 8d.”

Leland, speaking of the religious houses here says,

“I saw in the quire of the Blake Freres the tumbe of……… and a flat alabaster stone, with the name of Lady Isabel, wife to Sir John Beauchamp of Holt. And in the North Cross Aisle a tombe having the name of Roger Poynter, or Leicester, armed, and another seripture. These things brevely I markid at Leycester.”

Aug. 7, 1547, the king granted to Henry Marquis of Dorset and Thomas Duport, and the heirs of the Marquis, the whole house, and the site of it, together with such fishing rites as can be proved to have belonged to the friars in Leicester.

“Septimo die Augusti, 38 Hen. VIII. rex concessit Henrico marchioni Dorset & Thome Duport, & heredibus marchionis, totam domum & scitum domus dudum fratrum Dominicalium, vulgariter nuncupat’ ‘les Black-freyers.”

At the entrance of this Friary from the North gate of the, upon Mr. Noble erecting a house there, in 1718, was found a pot full of Roman coins.

In 1754, two elegant mosaic pavements, with the fragment of a third are going in a piece of of ground in this friary, then belonging to the late Rodger Rudding esq. of Westcotes, who died March 27, 1795; and not to the younger branched of his family. Some other pavements also seem to run under the present building.

“The North Bridge, now commonly called St. Sunday’s Bridge, has eight wet arches, the midmost high and wide; two more on the town side, small and useless, obstructed on both sides by dyers buildings, and made ground. It is 98 yards one foot long, five yards two feet wide; parapet walls about a yard high, their thickness one foot two inches. One of its arches, the one nearest the town, is pointed. The other nine are round. From the top of the parapet to the water is four yards and three quarters; the common depth of the water one yard eight inches, near the middle of the bridge, by the middle of the arch. I believe that when the two dry arches of St. Sunday’s Bridge possessed each a stream, the waters supplied a channel, or wet ditch, on the south east edge of the Abbey meadow; as the other arches, the north west current, by the Abbey; and it became an island in the manner of the Old Soar and rye Back Soar, whose water circulates here, running off by the North west side of Belgrave through its bridge.” — Preceding unsigned comment added by Me.Autem.Minui (talk • contribs) 05:42, 21 March 2024 (UTC)

Palmer Source

[edit]THE REVEREND C.F.R. Palmer. O.P. PAPER ON THE BLACKFRIARS OF LEICESTER PRESENTED TO THE LEICESTER ARCHITECTURAL ARCHEOLOGICAL SOCIETY MAY 28th, 1883[2]

[edit]The REV. C. F. R. PALMER, of St. Dominic's Priory, Maitland Park, Haverstock Hill, London, contributed the following Paper on:

THE FRIAR-PREACHERS OR BLACKFRIARS OF

LEICESTER.

THE Order of Friar-Preachers sprang out of a band of seven or eight Spanish and French priests, who went about Languedoc in the South of France, preaching in opposition to the powerful and rising sect of the Albigenses. This band was led by Dominic Guzman, a Spaniard of noble birth, who was born in the year 1170, at Calaruega in the kingdom of Old Castile, and became a Canon- Regular in the cathedral of Osma. He had been thus labouring in

(Page 43)

France for ten years, when he realized the idea suggested by the spiritual needs of the age and welfare of the church, in the establishment of a religious Order uniting the asceticism of monastic life with the active ministry; which would go far towards remedying the prevailing evils. In the year 1215, Dominic laid the foundation of his Order at Toulouse, with a community of seven brethren. The Order was approved and confirmed, December 22nd, 1215, by pope Honorius III. who gave it the title of Friar-Preachers.

The government of this religious body of men was wholly legislative, based on the mild and pliant Rule of St. Augustin, Jet subject directly to the supreme authority of the Roman See. It was centred in a master-general, while the provinces which national and local distinctions required were ruled by provincial priors, and the charge of each house was committed to a prior. The master-general was elected in a general chapter of the Order made up of deputies from each province; the provincial prior, in a provincial chapter of those members of the associated communities, who by learning or influence had acquired an elective right; and the conventual prior, in an assembly of the community. The houses were called indifferently, Friaries, as containing a number of Freres (brothers), or Priories, from their governing head.

As ascetics the Friar-Preachers were bound, explicitly by a Vow of obedience to the Rule of St. Augustin and to the constitutions regulated by the legislature; and implicitly by the vows of chastity and poverty. The austerities consisted in, the choral recitation of the divine office with the celebration of mass every day, and vigils of the dead eventually changed for the weekly office of the dead; claustral silence with study; perpetual abstinence from flesh-meat, and fasting from Holy Cross day (Sept. 14th) to Easter, with a strict advent and lent; and the exclusive use of woollen in clothing and bedding. The full habit consisted of a tunic (with a leathern girdle) and a loose scapular and a capuce, all white; and in public, and during winter in choir, a black cappa or cloak and capuce. Shoes and stockings were enjoined. On account of the cappa came the popular name of Blackfriars in England, although the same designation was sometimes given to the black-robed Friars or Hermits of St. Augustin. They were also termed Jacobins or Jacobites, especially in France, from their great house of St. Jacques at Paris. From the fifteenth century the name of Dominicans has distinguished them as followers of St. Dominic.

The vow of poverty not only forbade the personal possession of property, but even shut out the Order from holding in common any rents or lands beyond the site and shelter necessary for churches and dwellings. Thus stripped of all revenues the Friars were cast on the charity of the people for their maintenance, and…

(Page 44)

subsisted on alms begged mostly from door to door. And so was founded the first of the four great Mendicant Orders. But as times and customs changed, the rule was modified, at first in isolated cases by lawful authority, till at last pope Sixtus IV. by a bull dated April 18th, 1478, allowed the whole Order to possess lands, revenues, and other real property, and the general chapter celebrated in the same year at Perugia enforced the decree, which the Council of Trent afterwards approved. Thus the quest of alms was extinguished; and the vow of religious poverty became purely personal, not inflicting, indeed, the sordid and grinding want of the abject poor, but entailing the religious disability to hold the unsanctioned dominion of any property, and curbing needless expenses.

As teachers of the people these Friars exercised their ministry, untrammelled with those parochial duties and local ties, which would have absorbed their energies and crippled their action. They went up and down all the country preaching, hearing confessions, and celebrating mass and administering the holy communion. They taught from the professor's chair in the universities, established schools, and wrote copiously on almost every branch of divine and human sciences.

Such continues to be the constitution of the Dominican Order at the present day.

The patriarch of the Friar-Preachers died, August 6th, 1221, at Bologna, and was canonized, July 3rd, 1234, by pope Gregory IX. He had seen his Order, within five years, overspread Spain, France, Italy, and Germany, divided into seven provinces, and possessing sixty convents. He established the eighth province of England about two months before his decease.

From the second general chapter held in the end of May at Bologna, he sent thirteen brethren into England. These Friars reached London, August 10th, and Oxford August 15th, where they built an oratory, and began their charge of teaching in the university and preaching throughout the land. The Order made rapid progress, and spread from England into Ireland and Scotland. Within seventeen or eighteen years, in England they had fifteen sites; in 1277, there were forty convents in England and Wales, and at the general suppression in 1538, the number had increased to fifty-two convents with two subsidiary houses, and one establishment of Sisters of the Order engaged in the training and education of young persons of their own sex. The success of the Friars was mainly due to the influence which they obtained at the royal court under Henry III. and kept up till the House of Lancaster displaced the House of Anjou on the throne, after which their courtly prestige gradually waned. The greater number of their priories were founded by kings or nobles or persons in the upper ranks of life; some rose out of the piety of wealthy commoners; and a few were given by the clergy.

(Page 45)

The Friar-Preachers established themselves at Leicester in the earlier part of the reign of Henry III., but in what year is unknown, and who was the first patron or founder becomes a matter of conjecture, though the opinion of Nichols and the historians of the town of Leicester is supported by collateral evidence, against which there is nothing to oppose.

Now there was at this town an ancient parish church dedicated to St. Clement, the patronage of which belonged to the Abbey of St. Mary de Pratis, and in the year 1220, it was returned that the vicarage was so poor, that it scarcely sufficed to support a chaplain. The Matriculus dni. Ep. Linc. de omnibus ecclesiis in Archd. Leic'., 1220, thus records it: "Ecclesiæ S. Clementis patronus idem Abbas [Sanctæ Mariæ de pratis Leic.] quæ vix sufficit ad sustentationem capellani," "* Nothing later is found concerning this church, which disappears entirely from view; within seventy years it had ceased to belong to St. Mary's Abbey, for it is not mentioned in the Taxatio Ecclesiastica of pope Nicholas IV. in 1291, nor in the Taxatio spiritualium bonorum et temporalium Abbatis et Conventus Leicestrensis in 1292. Hence it would seem either that the church had been destroyed, or what is far more probable had passed into the possession of a Mendicant Order, whose scanty possessions had the privilege of exemption from taxation and subsidies; and when it is found that the priory church of the Friar-Preachers was dedicated to St. Clement, pope and martyr, it becomes as certain as it is possible to be without direct evidence of the fact, that the old parish church was given to these Friars by the Canons Regular of St. Augustin of St. Mary Pré or de Pratis at this town. The church stood within the town wall, between the North Gate on the East, and the river Soar on the West: the attached parish (which by their rule the Friars might not administer) was united chiefly to that of All Saints, perhaps in part to that of St. Nicholas. This transfer of the church may be dated about 1245; for the Friars were certainly at Leicester in 1252. A delegation was sent to the guardians of the Friar-Preachers and Friar-Minors of Leicester by pope Innocent IV. in the tenth year of his pontificate, to hear and determine a difference concerning tithes (at Bakewell, it is believed, in Derbyshire) between the Dean and Chapter of Lichfield and the Cluniac Prior and Convent of Lenton in Nottinghamshire; and the guardian of the Friar-Minors finished the commission "die sabbati post Purificationem S. Mariæ, A.D. 1252."+

If the Friars received possession of the church and churchyard of St. Clement, they had then only to secure sufficient ground for the site of their cloistral dwelling and offices, and for a small homestead to supply their immediate wants. Stow states that the Blackfriars' house here was founded by an Earl of Leicester; but +Tanner, Not. Mon.

Cotton MSS. Nero D x.

(Page 46)

if the authority he quotes, "rec. 18 Edw. III.," refers only to the inquisition of that date, it is shown there at most, that the Friars had acquired some land from Henry Plantagenet, who held the earldom from 1324 to 1345. Still Stow is probably correct; and the founding of the house, if not of the church, must be set down to the famous Simon de Montfort, who was made Earl of Leicester in 1230, and was slain at the battle of Evesham in 1265. The Priory held a considerable piece of land pertaining to the Honour of the Castle of Leicester, for which land the yearly rent of 3s. was paid; and it could have been obtained only through the favour of Earl Simon.

The Friars had also another piece of land, at the rent of 14d., rendered every year to the Cistercian Abbey of Garendon: the Registrum Abbatiæ de Gerondon throws no light on this payment; but the Valor Ecclesiasticus of 1535 sets down among the rents and farms of divers tenants of that house "in Leicester, xiiijd."

It was probably for land the Friars had obtained as their site that the Premonstratentian Abbot and Convent of Croxton bestowed on them in charity an annual rent of 12d. and two capons given to the Abbey by Peter, Rector of Eastwell, from a messuage in the parish of St. Clement, in the tenure of Richard de Walton. The Reg. vocat. "Domesdey Canobii de Croxton" (fol. 28a) has this entry: "Habemus in Leycestria. . 6. Item habemus de Dono Petri quonda' Persone de Estwelle annuu' Redditu' xiid. & ii. Caponu' in eadem Villa in puram Eleemosina', recipiendu' de quodam Mesuagio in Parochia S. Clementis, quod Ricardus de Walton tenuit. Quem quide' Redditu' Fratres Predicatores manentes in Leycestria habent de dono nostro, Intuitu Caritatis, imperpetuu'."+ There is no clue to fix the date of the gift to the Friars: among the rectors of Eastwell occur the names of Roger the chaplain, 1209; Peter de . . . . 1226; and Robert de Hawethorne, 1285. The gift, however, relieved the Friars of a yearly service, which thus became extinguished.

These three rents were evidently attached to the primitive site of the Priory, as they were not due for any later addition of lands. The Friars gradually extended their lands, and added to the buildings. A writ was issued January 14th, 1284-5, to enquire whether, without injury, Robert de Wylouby and Alice his wife might assign to the Friars a plot of land, and Robert also another plot of land which he had by the gift of Isabel, daughter of Gylot le Taillur. The inquisition made before the Sheriff, February 16th, returned a favourable answer, and declared that the two plots were held of Edmund, Earl of Leicester, by service of 9d. a year, and that they contained 104 feet in length and four score and ten…

Lansdowne MSS. 415.

+ Old MSS. of Brit. Mus. 493. Nichols, Hist. of Leicestershire.

(Page 47)

feet in breadth.* No mortmain licence appears; so that there is some doubt whether the transfer of the plots was carried into effect. Edward I. gave, March 12th, 1300-1, seven oaks fit for timber out of the forest of Rokyngham, for some houses which the Friars were about to erect,+.

About the time of Edward II. several plots of land contiguous to the site were given to the Convent by Peter Peinfot, Richard Fode, Robert de Dalby, William de Morton, and Isabel de Wylughby. Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, as supreme lord, con- firmed the gifts, and at the same time gave licence to the Friars to enclose a void plot below their garden and churchyard. This void plot extended from the Waterlock towards the North Gate. Immediately after the execution of the Earl, in 1322, for rebellion against the King, the Friars obtained a royal confirmation of his grant, May 18th; and fourteen years later had another ratification, June 5th, 1336, from Edward III. in pure and perpetual almoign.§

After 1824 the lands were increased by another addition, which seems to have been the last, and to have secured all the territorial requirements of the community. The Friars acquired, contiguous to their homestead, from Henry, Earl of Lancaster (and Leicester) a lane 300 feet long and 30 feet broad, and from Lawrence de Belgrave two plots of land 300 feet long and 200 feet broad: and a royal pardon granted, June 11th, 1344, after a due inquisition had been held, remedied all breaches of the statutes of mortmain, and empowered the Friars to retain the whole, which otherwise would have been forfeited to the crown for want of the King's licence.

The scantiness of the notices of alms and gifts bestowed on the Friar-Preachers of Leicester, by kings, nobles, and fellow-towns-men, is balanced in some measure by variety and interest. Soon after Michaelmas, 1291, the executors of the will of queen Eleanor of Castile gave 51. to this house. Edward I. gave an alms of 21s. 4d., December 12th, 1300, for two days' food, through F. Henry de Beydon:** being at the accustomed rate of a groat each day for thirty-two religious. Edward II. arriving at Leicester, in October, 1307, gave 13s. 4d. on the 10th, for a pittance.++ Again during his stay in this town, February 7th, 1319-20, he bestowed an alms of 10s. for the same through F. William de Pollesworth. Edward III. gave 10s., January 8th, 1328-9, to the thirty Friars, 4d. each, for a day's food, through F. Geoffry de Wardon:§§ and also 10s. 8d., February 14th, 1334-5, to the thirty two Friars, through F. John de Clifford. Amongst the MSS. of…

(Page 48)

the Borough of Leicester, preserved in the Muniment Room, is a Grant, dated in 18 Edward III., 1344, by Henry Earl of Lancaster to the Mayor and Commune of Leicester of a piece of ground for a place of easement, instead of another piece granted for the same purpose to the Friar-Preachers.

Sir Thomas de Chaworth the elder, knt., by will dated November 6th, 1847, bequeathed half a mark to each Convent of Friar Preachers, Minors, Augustinians, and Carmelites of Stanford, Leycestre, Notingham, and Derby.* Henry, Duke of Lancaster, Earl of Derby, Lincoln and Leicester, and Steward of England, by deed dated February 28th, 1356-7, granted leave to the prior and convent of the Friar-Preachers of Leicestre to fish every Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday, during the day but not at night, in the river Sore below their close, with a flunet of suitable mesh, so as not to destroy the young fish.t William, Lord Ferrers of Groby, by will of June 1st, 1368, left bequests to the Friars at Leicester, Maldon, Stebninge, and Woodham: he died January 8th, 1371-2. John, Duke of Lancaster, being at Leicester, August 18th, 1375, gave two oaks, evidently for fuel. § Sir William Chaworth, knt., by will dated December 16th, 1398, and proved January 5th following, gave 40s. to the Friar-Preachers of Leycestre, to pray for his soul and the souls of all the faithful. John Mersdon, rector of Thurkeston (co. Leic.) by will of October 10th, 1424, proved October 20th, 1425, bequeathed 138. 4d. to every house of Mendicant Friars within this town. William Hastyngs, knt., Lord Hastyngs, by his will dated June 27th, 1481, ordained "that Cli. be disposed among pore folkes, as soon as it may be conveniently, after my decese; and to the Friers of Nottingham, Northampton, Leicestre, and Derby, and to other persons and pore folkes of the said shires, by the discretion of my said executors . . . . . to the Grey Friers of Leicestre x", and either of th'other two houses of Friers of the same towne, Cs."** The Corporation of Leicester, by an act of common hall, September 21st, 1505, granted to F. William Seyton (Layton) prior and to his successors, the pasture of two cows in their common pasture called the Cow Hey; for which the prior had paid twenty marks (shillings) and engaged that his house should pray for them for ever. Sir Rauf Shirley, of Staunton Harold co. Leic., knt., January 2nd, 1516-7, bequeathed 10s. to every house of Friars in…

Regist. of Grants of Duchy of Lanc. No. xii. fol. 230 b. Test. Ebor. Lambeth. Chichele 1, 390 b. tt Nichols. Vol. I. part ii. page 296. But p. 387, in the extract from the old Hall Book of the Mayor, etc., he gives Seyton for Layton, and shillings for marks. The extract from the old Hall Book is thus given in Throsby's History and Antiquities of Leicester, 1791. "At a Com'n hall halden at Leicest'r the 21st day of Septemb'r the 21st yere of o'r Sov'aign King Henry VII. It is agreed Stablyshed & affarmed & gyfted by Robt. Orton then Meir of the said Towne his brethren & the 48 in the name of the holle body of the same to free Will'm Ceyton."

( Page 49)

Leicester, to pray for his soul.* Thomas Eyreke, of Leicester, August 25th, 1517; "I will that the iij orderis of freeris of Lecester bring my body to my gave, and ev'y of them to haffe xxd."+ Thomas Newcome of Leicester, bellfounder, by will dated March 20th, and proved August 25th, 1520, bequeathed "to every one of the places of friars in the said town of] Leicester, iij. iiij'." Hugh Yerland of Loughborow, May 15th, 1521, bequeathed "to iij orders of ffreres in Leicester for xv masses, v." The Wardens and Company of Shoemakers at Leicester agreed to pay ten marks (shillings) to the Friars, over and above the usual offering duties, to have their prayers.||

The provincial chapters of the Order were celebrated in this Priory probably on the average of every twenty or twenty-five years certainly they were held at Leicester, in 1301, at the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin (September 8th etc.); in 1317, at the Assumption (August 15th etc.); and again in 1334. For each of these, payments were made as royal gifts out of the exchequer. Thus 10l. was given, August 19th, 1301, through F. Adam Percy to F. Geoffrey de Wyrksopp prior of York, for two days' food of the capitular fathers; 151., July 4th, 1317, to F. William de Swyneford of the Leicester Convent, by a tally on the sheriff of the cos. of Warwick and Leicester, being 100s. from the king, 100s. from the queen his consort, and 100s. from their sons ;** and 151., May 27th, 1334, for three days' food, the alms being equally as before from the king, queen, and their children.++ In the chapter of 1317, F. John de Bristol was elected provincial.

The names of none of the Priors and religious appear besides those which are mentioned in the present article. F. Henry de Pollesworth probably belonged to a good family originally from Polesworth, which was settled at Tamworth in the fourteenth century.

"Of the Black ffrerys of Leie' bey'ing that tyme and to all his Successors for ever the Pasture of 2 kye in o'r commynalte callyd ye kowe hey to be as free as any of us w'thout lete ympedyment of any of us for the which he gaffe us xxs. and he and his howse to pray forus forever. In Witness of the same we gyffe unto hym & his howse o'r seale of office there beying Chamberlens Will'm Mellow & W'm Burgen (Corporation Records.)"

Nichols' version runs as follows: "At a common hall, it is agreed, and given to Frere William Seyton, prior of the Black Friers of Leicester, and to all his successors for ever the pasture of two kye in our commonalty called The Cow-hey, to be as free to them as any of us, without let or impediment of any of us; for the which he gave us twenty shillings, and he and his house to pray for us for ever. In witness of the same, we give him and his house our seal of office." + Leicester Probate Court.

Leic. P. C. We are indebted to the kindness of the Rev. W. G. Dimock Fletcher, M.A., for the extracts from the wills at Lambeth, in the P. C. C., and in the Leicester Probate Court. Nichols. Here again it seems that marks is put for shillings. In the following year (1532), the Company of Shoemakers made a similiar gift of 10s. to the House of the Augustinian Friars.

(Page 50)

There were three Friars of some note in their own days, who bore the surname of Leicester; but it is not evident that they were at any time attached to this Priory.

F. Walter de Leycester was promoted by pope Eugenius IV., July 13th, 1431, to the Bishopric of Ross, but whether in Scotland or Ireland the brief does not express.

One F. Andrew of this Convent, being in deacon's orders, went, in 1526, with some complaint to the master-general of the Order, but had not received the necessary licence to resort in person to the Roman Court. The master duly punished him for this breach of monastic discipline, and May 6th, sent him back to his province, with injunctions to the provincial, to be satisfied with the penalty he had already undergone; to let him hear the reason of his being deprived of place and vote by his prior; and to deal compassionately with him, and if he was qualified to have him raised to the priesthood according to the constitutions of the Order.†

Very little is known with certainty concerning the burials which took place within the precincts of this religious house and church. Shortly before the dissolution of monasteries, Leland, in describing Leicester, after speaking of the Grey Friars, says, "I saw in the Quire of the Blake-Freres the Tumbe of and a flat Alabaster Stone with the name of Lady Isabel, Wife to Sr. John Beauchaump of Holt. And in the North Isle I saw the Tumbe of another Knight without Scripture. And in the North Crosse Isle (a Tombe) having the Name of Roger Poynter of Leicester armid." Then he describes other churches, and adds the following. "A litle above the West bridge the Sore castith oute an Arme, and sone after it commith in again, and makith one streame of Sore. Withyn this Isle standith the Blake-Freres very pleasauntly, and hard by the Freres is also a Bridge of Stone over this Arme of Sore." Here Leland accurately points out the site of the Priory of the Augustinian Friars, and evidently uses loosely the popular name sometimes made common to the two Orders.

The Priory of St. Clement of Leicester, of the Order of St. Dominic, was also called the "Blak Frears in le Asshes," and was thus distinguished from the Augustinians: it is supposed that a number of ash trees grew about the house, so as to give it a particular mark. After the year 1478, parts of the lands attached to the Priory were let to tenants. F. Ralph Burell, D.D., prior and the convent, September 10th, 1538, leased to Thomas Katlyn, bailiff of Leicester, a dwelling-house within their precincts, called Roberte Orton's ous, where the same Robert lately dwelt, with all orchards, gardens, and closes, as well in tillage as in pasture, and "wone holte of willowes" near the Soure, also the churchyard in the holding of Christofer Lambarde, with all herbage grounds within the limits and precincts of the house; to be held from the

- Arcbiv. Apost. in Palat. Vaticano.

† Regist. mag. gen. ord. Romæ.

(Page 51)

present date for the term of threescore years, at the yearly rent of 408., paid at Ladyday and Michaelmas. The lessee was to have hedgebote, with "loppe, toppe, & croppe' of all wood and underwood growing on the grounds; and he was to find "all manor of rep'açons, sauynge stone, tymber, lathe, & nayle," which the Prior and Convent should provide: and they should have power of re-entry, if the rent was behind for a month, and no sufficient distress could be found upon the ground.*

F. Ralph Burrell, the last prior, was B.D. of Cambridge, 1526, and afterwards commenced D.D. there or elsewhere.† Under the compulsory destruction of monastic institutions in England, the breaking up of this Priory was a voluntary act on the part of the ten Friars, who formed the community. The formal act of surrender of the house and lands of the Priory of St. Clement of the Order of St. Dominic, commonly called "le Blak Frears in le Asshes," was dated November 10th, 1538, and was subscribed,

RAD'M BURRELL, p'ore' ac Doctore' sac' theologie. W'LL'M HOPKYN', suppreor'. [It may be Kopkyn'.] JHOHANE' HARFORD. RICHARDU' YNGYLBYE. ELLIZEU' GEM'. JOHANNE' HEYNE. JOH'EM KOK. RIC' BLALVYN. EDWARD' WHOWARK. p' me ROBERTU' SUTTU'."

The Prior and others, on the 13th, acknowledged and delivered their deed before Thomas Catlyn, Geo. Assheby, and John Smyth, who had full powers from the king to receive the act, in the presence of Robert Cotton, Walter Garset, Geo. Cadman, John Olyff, and many others. To this deed was attached the conventual seal, which is still in rather good preservation.

It is vesica-shaped, and bears the full figure of a pope, standing on a bracket and under a double canopy, vested in alb and chasuble, with the tiara on his head and triple crosier in his left hand, the right hand being raised in benediction: inscription,

+ sigillu · comune · fratru p'dicator' cobentu · Leyces.

Nichols gives an engraving of the seal, on a diminished scale; but substitutes minoru' de Leycestre for the last two words.

Thomas Catlyn, who enforced the surrender and seized the goods, carried the deed to London, and delivered it into the court

(Page 52)

of chancery, where it was endorsed on the close rolls:* and at the same time he hastened to secure to himself the lease of the house and lands, by appearing, November 24th, in the court of augmentations, and having his deed sanctioned. After Christmas, January 12th, he sent 40oz. of white plate from the houses of the Friars of Leicester into the royal treasury; and on the 14th, had his deed duly enrolled. The cloisteryard and the residue of the grounds and buildings which the Prior and Convent had kept in their own hands were also committed to his charge; and August 4th, 1539, he became the tenant of them at the rent of 20d. a year, and when he applied for remuneration in keeping guard while they were unoccupied, he received 16s. 8d. from the crown for his trouble. By the dissolution three rents became extinguished, which had been paid for lands: being 3s. to the king as Lord of Leicester Castle; 3d. to the king for a toft at the South Gate, in the Fryers orchard towards the South Gate of the town, where stood a barn that had been given to the Prior and Friars by Keye, widow; and 14d. to the Monastery of Garroden. § Keye's gift was probably the endowment of a mortuary foundation.

Thus Thomas Catlyn gent. continued to hold the lands of the late Convent of Leicester, at the rent of 21. 1s. 8d. a year. Henry Marquis of Dorset and Thomas Duport [his attorney or trustee?] applied, December 4th, 1545, to purchase the whole, and the particulars were drawn up for them. The royal grant of sale was made, August 7th, 1546, to the Marquis and Duport, and to the Marquis's heirs and assigns for ever; and included, the site of the Blacke Frears, Rob. Orton's house, and all gardens, orchards, closes, and enclosures, with the willow-bed next the Sour, the churchyard, cloysteryarde, and all buildings, with the exception of bells, and metals, stone and glass not for gutters and windows. The whole was to be held in free and common socage, for the yearly rents of 4s. for the site, house, etc., and 2d. for the cloisteryard, etc.; and the grantees were to have all issues from the preceding Michaelmas.

The property has since passed through various hands. No traces of the buildings are now to be seen: how or at what time the buildings were destroyed does not appear. They were certainly standing about 1620; for Burton mentions that, "in the cloister in a niche in the wall, not long since was found a coffin of stone, wherein was a corpse in bond leather."** The limits of the Priory-grounds being still extra-parochial are very accurately known, and contain 16c. It is evident from some old writing that a lane running from…

(Page 53)

the North Gate, and turning westward to the Friars, and then running southward between the Friars and the backs of the houses opposite All Saints' Church, was formerly called St. Clement's Lane; and so it is probable that St. Clement's Church stood in or near it.*

In Speed's Plan of Leicester published in 1610, the site of this Priory is not noticed; but the name of Black fryers lane is given to a short byeway near the South Gate, at the site of the Grey Friars, where the Friars' Orchard before mentioned probably lay. Stukeley's Plan, in 1723, shows that the town wall ran through the Priory lands from the North Gate to the Soar, and cut off a considerable strip parallel with the Soar Lane: this may have been the plot which Thomas Earl of Lancaster allowed the Friars to enclose. At the entrance of this Friary from the North Gate, upon Mr. Noble erecting a house there, in 1718, was found a pot full of Roman coins. In October, 1754, two very fine mosaic pavements, with the fragments of a third, were brought to light in a piece of the ground belonging to Rogers Ruding, Esq., who died March 27th, 1795, and then to the younger branches of his family. Some other pavements also seemed to run under the buildings. Nichols has good engravings of these pavements.

The only local memorials of this ancient Priory now consist in the names of some petty streets and lanes within and bordering on the site. Thus there are found, Blackfriars' Street, Friars' Causeway divided by Bath Street, Friars' Place, and Friars' Road. Ruding Street received the name of a former owner: whether Orton Street had any connection with the ancient Orton's house is not evident.

May 28th, 1883.

THE REV. J. H. HILL, F.S.A., in the chair.

Billson Sources

[edit]See Charles J. Billson. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Me.Autem.Minui (talk • contribs) 20:11, 21 March 2024 (UTC)

C.J. BILLSON, MEDIEVAL LEICESTER (1920), CHAPTER 1, SECTION 1, & Section 4, ON THE NORTH QUATER, ON THE WEST QUATER.[3]

[edit]A table in this section shows us that North Leicester only had a taxable population of 59 in 1269 and 66 in 1288. It also shows us that in West Leicester there were only 55 taxable residents in 1269 and 56 in 1288 - perhaps because the priory had taken over much of the property at that time and wasn’t taxable. I haven’t been able to upload it.

I. THE NORTH QUARTER. The Northern, or North-western half of Leicester was so ruthlessly and completely destroyed after the siege of the town in the year 1173 that it remained for many centuries the least populous…

IV. THE WEST QUARTER. The remaining quarter of the town is that contained by the Town Wall on the North, the river on the West, the High Street on the East, and Hot Gate and Applegate on the South.

It comprised the ancient Churches of St. Nicholas and St. Clement, and the Monastery of the Black Friars, which occupied 16 acres. There, too, lay the old Blue Boar Inn, and the earliest halls of the Guild Merchant.

Among the few lanes in this quarter were the Guildhall Lane, St. Clement's Lane, Friars' Causeway, Deadman's Lane, Jewry Wall Street, and Talbot Lane.

The Guildhall Lane was described in 1301 as "the lane which leads from the High Street to the Moothall"; and in 1341, when it was paved, as "the lane towards the Guildhall." In the next century it was called "Mayor's Hall Lane." It ran out of the High Street by the side of the Blue Boar Inn, and has since been known unto the present day as Blue Boar Lane — a name said by Hutton to have been at one time corrupted into "Blubber Lane."

St. Clement's Lane was a long passage running from the North Gate westward to the Black Friars and St. Clement's Church, and afterwards turning south, and passing between the grounds of the Black Friars and the backs of the houses which stood facing the old High Street opposite All Saints' Church. It was also known as "The Black Friars Lane." Thus, the first Town Ward of 1484 beginning at the High Cross extended to "the Black Friars Lane." Another name was "the lane of the Friars Preachers." The parcels contained in a deed of 1498 throw some light upon the topography of this quarter. Four cottages were demised which lay together "in the lane of the Friars Preachers, between the land late William Here's on the East and the said lane on the West, and stretching from the tenement of Robert Metcalf, butcher, on the South, to the lane which leads to the house of the Friars on the North." It appears from this description that the "Lane of the Friars Preachers," i.e., St. Clement's Lane, lay at right angles to another lane which led to the Friars' House, the Friars' Causeway, probably, of the present day. It is this path from the High Street to the Friars which was described in 1373 as "the lane leading to the Friars Preachers."

The Southern portion of St. Clement's Lane became known in later years as Deadman's Lane, and it is so called in Cockshaw's plan of Leicester dated 1828, But in Combes' map of 1802, which was published in Miss Watts' "Walk through Leicester," the whole of St. Clement's Lane is marked Deadman's Lane."

The ground containing the relic of Roman occupation known as the Jewry Wall, is frequently referred to in the 14th and 15th century Records as the Holy Bones. It is thought that the district in which it lies was known in the time of the Norman Earls as Jewry, or Jews' quarter, prior to the Charter of 1250 which provided that no Jew should remain in Leicester. Hence the Roman remains were called the Jewry Wall, and the continuation of Blue Boar Lane which passes it became known as Jewry Wall Street.

The street still called Talbot Lane, which runs into Apple Gate from the North, was probably existing in mediæval times. The Talbot Inn, from which it may have taken its name, was standing at the end of the 15th century. Possibly both Lane and Inn were christened after a piece of ground known as the Talbot.

C.J. BILLSON, MEDIEVAL LEICESTER (1920), CHAPTER 6, SECTION 1, ON THE CHURCH OF ST.CLEMENT.[4]

[edit]“The ancient parish church of St. Clement belonged to Leicester Abbey, and stood within the walls of the town, between the North Gate and the River Soar. The parish suffered very severely from the sack of 1173, and in 1220 it was so poor that it could hardly support a chaplain. By the year 1291 it had ceased to belong to Leicester Abbey. But it had not been destroyed; and moreover the Rev. C.F.R. Palmer was in error when he wrote, in his account of "The Friars Preachers, or Black Friars of Leicester," "Nothing later" (than 1220) "is found concerning this church, which disappears entirely from view." It is true that, in a Roll of Leicester churches of the year 1344, St. Clement's is wholly omitted, but it was in use a few years before. On July 8th, 1331, a licence was granted for the alienation in mortmain by Philip Danet to the master brethren and sisters of the hospital of St. Leonard, Leicester, of 5 messuages and 7.5 virgates of land in Whetstone, Croft and Frisby-by-Galby to find a chaplain to celebrate divine service daily in the Church of St. Clement, Leicester, for the soul of the said Philip Danet, and for the souls of his parents brothers and sisters and of Robert Burdet and Petronilla his wife. The canons of the Abbey must have parted with the church some time between 1220 and 1291, and there can be no doubt that they gave it to the Friars Preachers, or Black Friars, who came to Leicester early in the reign of Henry III., before 1253, and settled in the grove of ash-trees near to St. Clement's church. The parish by their rules the Friars could not administer, but the church, dedicated to St. Clement, pope and martyr, became the church of their priory.

“The absorption of St. Clement's church in the Black Friars is a very unusual incident. Mr. A. Hamilton Thompson, although his knowledge of mediaeval ecclesiology is remarkably wide, cannot recall a similar instance. In his opinion, which he kindly allows me to quote, Danet's proposed grant indicates that "if St. Clement's had been given over to the Black Friars, it still had parochial rights, which it would have been difficult to do away with; otherwise the grant would have been made to the Friars themselves. Possibly the nave still belonged to the parish. As regards Friars' churches, however, this arrangement was most unusual; but the Abbey, in granting the church to the friars, could only have surrendered the rectorial tithes and the chancel, and had no power to oust the parishioners from the nave without special agreement. The endowments of the church were very poor. The secular vicar appointed in 1221 had as his stipend merely the daily allowance of a canon in the Abbey, so that it can have been no great sacrifice to the Abbey to part with it. I should not be surprised if the chantry of 1331 was contemplated in order to keep up the parochial services: the normal services in parochial chapels and churches, where there was no vicarage ordained, were frequently called chantries, and were precisely on the same footing."

“"It appears from some old writings," says Nichols, "that a lane from the North Gate, turning westward to the Friars adjoining, and then running southward between the said Friars and the backs of the houses opposite to All Saints' Church, is called St. Clement's Lane, and therefore it is probable that the church was situated in or near it."

“The church was visited by John Leland, the antiquary, about the year 1536. He noticed a knight's tomb in the choir, and a flat alabaster stone with the name of Lady Isabel, wife to Sir John Beauchamp of Holt; and in the north aisle he saw the tomb of another knight, without scripture, and in the north cross aisle a tomb having the name of "Roger Poynter of Leicester armed," (? armiger, i.e., esquire). Shortly after his visit, the church was demolished.

A century later its very memory was beginning to fade away, for, in connection with the Metropolitan Visitation which Archbishop Laud held in 1634, Sir John Lambe made the following note:— "St. Clement's, Quaere, where it stood? no such now."”

VCH Sources

[edit]The two articles indicate the projects decision found in the Victoria County History reflects their decision not to equate St Clement’s Parish Church with the priory Church of St Clement’s Priory.

VICTORIA COUNTY HISTORY, A HISTORy OF THE COUNTY OF LEICESTERSHIRE (1954), VOLUME II, ON FRIARIES, FRIARIES IN LEICESTER[5]

[edit]The house of the Dominican friars at Leicester is said to have been founded by an Earl of Leicester under Henry III. (23) The first reliable reference to the Dominicans at Leicester relates to 1284, when an inquisition was held concerning the proposed grant to them of two plots of land in the borough. (24) Their friary stood on an island formed by two arms of the River Soar. (25) According to Nichols (26) the Dominicans obtained the parish church of St. Clement, at Leicester, as their conventual church. Such an arrangement would have been very unusual, (27) and the evidence for it seems to be inadequate. (28) A 15th-century seal of the house bears the figure of St. Clement, (29) and the friary church is said to have been dedicated to the saint, (30) but these facts are hardly sufficient to prove that the friars acquired possession of a parish church.

In 1291 Queen Eleanor's executors gave £5 to the Leicester Dominicans, (31) and in 1301 they received a royal gift of seven oaks from Rockingham Forest, for house building. (32) Provincial chapters of the order were held at the Leicester house in 1301, 1317, and 1334. (33) Royal gifts of money to thirty Dominicans at Leicester in 1328-9, and to thirty-two in 1334-5, (34) indicate the size of the convent in the 14th century. The garden and cemetery of the friary are mentioned in 1336. (35) During the 14th and 15th centuries the Dominicans received many minor gifts and bequests. (36) In 1489 Henry VII ordered oaks to be delivered to the Dominicans of Leicester for the rebuilding of their dormitory. (37)

The friary was surrendered in November 1538 by the prior and nine others. (38) Part of the property of the house was being leased, in 1538, for a yearly rent of £2, and the remainder was valued at only 1s. 8d. The net yearly income, as given in the First Minister's Account, was only £1. 19s. 8½d. (39)

Priors of The Dominicans

- John Garland, occurs 1394. (40)

- William Ceyton, occurs 1505. (41) *

- Ralph Burrell, occurs 1538. (42)

Seal The 15th-century seal of the Leicester Dominicans is a large oval, 2⅛ by 1⅜ in.; it depicts St. Clement standing under a canopy, his right hand raised in blessing, and his left holding a cross; The legend is: 'SIGILLF COMUNE FRATRF PREDICATORF CPVENTF LEYC'.' (43)

Sources

- 23. Dugd. Mon. vi (3), 1486; T. Tanner, Notitia Mon. (1744), 245, note b, quoting a brief of Innocent IV, states that the Dominicans were already established at Leic. by 1252. The brief in question is, however, apparently that printed in Gt. Reg. of Lich. Cath. (Wm. Salt Arch. Soc., 1924), ed. H. E. Savage, 69-70. The Dominicans mentioned in this brief are those of London, not of Leic.

- 24. C. F. R. Palmer, 'The Friars Preachers or Black Friars of Leicester', T.L.A.S. vi, 46-47.

- 25. Leland's Itin., ed. Lucy Toulmin-Smith, i, 16.

- 26. Leics. i, 295.

- 27. C. J. Billson, Medieval Leic. 70.

- 28. The licence for the foundation of a chantry in St. Clement's in 1331 makes no mention of the Dominicans: Cal. Pat., 1330-4, 156.

- 29. B.M. Seals, lxvi, 66.

- 30. Dugd. Mon. vi (3), 1486.

- 31. T.L.A.S. vi, 47.

- 32. Cal. Close, 1296-1302, 434.

- 33. T.L.A.S. vi, 49.

- 34. Ibid. 47.

- 35. Cal. Pat., 1334-8, 278.

- 36. T.L.A.S. vi, 43-53; Leic. Boro. Rec., 1103-1327, 295; John of Count's Reg. (Camden Soc., 3rd ser. xxi), ed. S. Armitage-Smith, ii, 322.

- 37. Materials for the Hist. of Hen. VII (Rolls Ser.), ii, 458.

- 38. L. & P. Hen. VIII, xiii (2), p. 307; T.L.A.S. vi, 51.

- 39. Nichols, Leics. i, 296; S.C. 6/Hen. VIII/7311, m. 66.

- 40. Gibbons, Early Linc. Wills, 53.

- 41. Leic. Boro. Rec., 1327-1509, 375.

- 42. L. & P. Hen. VIII, xiii (2), p. 307.

- 43. B.M. Seals, lxvi,

VICTORIA COUNTY HISTORY, A HISTORY OF THE COUNTY OF LEICESTERSHIRE (1958), VOLUME IV, ON THE ANCIENT BOROUGH: LOST CHURCHES, ST. CLEMENTS.[6]

[edit]It is probable that the advowson of St. Clement's, like those of other churches in Leicester, was given by Robert de Beaumont to the college of St. Mary de Castro in 1107, and transferred to Leicester Abbey in 1143. (17) In 1220 St. Clement's is recorded as being one of the churches in Leicester which belonged to the abbey, but the church, which was apparently already appropriated, then scarcely sufficed to support a priest. (18) In 1221–2 a vicarage was established at St. Clement's, the vicar being allowed a yearly stipend of 20s. and a corrody at Leicester Abbey, besides a corrody for his clerk. (19) The only later mention of the church occurs in 1331, when Philip Danet received a royal licence to give lands to the hospital of St. Leonard at Leicester so that the hospital might find a chaplain to perform the divine offices in St. Clement's Church. (20) Nichols quotes a deed referring to a St. Clement's Lane which ran towards Black Friars from near All Saints' Church, and on which he supposed that St. Clement's lay. (21) He advanced the theory that the church was given to the Dominicans, (22) but there is no direct evidence of this, and such a development would certainly have been unusual, though perhaps not unknown elsewhere. (23) St. Clement's had disappeared by 1526. (24) Sources

- 17. V.C.H. Leics. ii. 45.

- 18. Rot. Hugonis de Welles, i. 238.

- 19. Ibid. ii. 286; Hamilton Thompson, Leic. Abbey, 160.

- 20. Nichols, Leics. i. 295; V.C.H. Leics. ii. 34; Cal. Pat. 1330–34, 156.

- 21. Nichols, op. cit. i. 295; Billson, Medieval Leic. 70–71; see also J. Throsby, Hist. of Leic. 234.

- 22. Nichols, op. cit. i. 295; Billson, op. cit. 70–71.

- 23. W. A. Hinnebusch, Early Eng. Friars Preachers, 133 n. In nearly all the cases cited, however, the evidence is not strong: see V.C.H. Leics. ii. 34.

- 24. It is not included in the churches of the deanery of Christianity at Leicester in 1526: A Subsidy Collected in the Dioc. of Linc. in 1526, ed. H. E. Salter, 113–14. St. Clement's is also omitted from the 1535 Valor: Valor Eccl. (Rec. Com.), iv. 148.

Disputed Questions on Locations

[edit]The questions of location, though not as contested as the question of origin and almost rendered mute by archeology, is not an area of complete agreement in the sources. The dispute divides into two heads. First, was the priory church of St Clement’s the pre-existing parish church of St Clement’s? And Second, was the priory on an island in the River Soar?

1. Did the ancient Parish Church of St Clement’s become the Priory Church of the Blackfriars?

[edit]The Priory Church was either:

- 1. The chapel built by the Blackfriars for themselves separate to but near St Clement’s[7]

- 2.1. St Clement’s Parish Church with the parish retained in the nave, either served by the Dominicans or by a chaplain.[8][9]

- 2.2. St Clement’s Parish Church building, the parish outside priory boarders dissolved.[10]

On Position 1. The Victoria County History denies the claim of John Nichols that the Parish Church of St Clement’s was a priory Church on the grounds that it would be unusual. It states it twice in the two separate articles, the logical consequence of dichotomising parish and priory.[7] In the 1954 article on Blackfriars in Leicester:

“According to Nichols (26) the Dominicans obtained the parish church of St. Clement, at Leicester, as their conventual church. Such an arrangement would have been very unusual, (27) and the evidence for it seems to be inadequate.”

And in the 1958 article on the Parish of St Clement:

“ Nichols quotes a deed referring to a St. Clement's Lane which ran towards Black Friars from near All Saints' Church, and on which he supposed that St. Clement's lay. (21) He advanced the theory that the church was given to the Dominicans, (22) but there is no direct evidence of this, and such a development would certainly have been unusual, though perhaps not unknown elsewhere (23) Note 23. = “W. A. Hinnebusch, Early Eng. Friars Preachers, 133 n. In nearly all the cases cited, however, the evidence is not strong: see V.C.H. Leics. ii. 34.”

On the other hand Nichols accepts the idea as totally uncontroversial, calling the poverty of the parish and the friars need of a home ‘provident’. He writes of the question thus:

“The Church of the Dominicans, or Friars Preachers, commonly called Black Friars of St Clement’s, or Le Blak Frears in le Ashes, was founded by Simon de Montfort the second Earl of Leicester of that name; and was dedicated to St Clement. The Matriculus of 1220 informs us that the vicarage of St. Clement’s was then so poor that it was scarcely sufficient to maintain a Chaplain; and therefore it is likely that the church was providently given to these Friars Preachers to officiate in; and Mr Carte supposed “in le Ashes” related to the many ash-trees which of old grew in their precincts, and that they had the title St Clement because they were situated in that parish.“ (see full text below)

The Rev. Palmer has this to say on the church:

“Now there was at this town an ancient parish church dedicated to St. Clement, the patronage of which belonged to the Abbey of St. Mary de Pratis, and in the year 1220, it was returned that the vicarage was so poor, that it scarcely sufficed to support a chaplain. The Matriculus dni. Ep. Linc. de omnibus ecclesiis in Archd. Leic'., 1220, thus records it: "Ecclesiæ S. Clementis patronus idem Abbas [Sanctæ Mariæ de pratis Leic.] quæ vix sufficit ad sustentationem capellani," "* Nothing later is found concerning this church, which disappears entirely from view; within seventy years it had ceased to belong to St. Mary's Abbey, for it is not mentioned in the Taxatio Ecclesiastica of pope Nicholas IV. in 1291, nor in the Taxatio spiritualium bonorum et temporalium Abbatis et Conventus Leicestrensis in 1292. Hence it would seem either that the church had been destroyed, or what is far more probable had passed into the possession of a Mendicant Order, whose scanty possessions had the privilege of exemption from taxation and subsidies; and when it is found that the priory church of the Friar-Preachers was dedicated to St. Clement, pope and martyr, it becomes as certain as it is possible to be without direct evidence of the fact, that the old parish church was given to these Friars by the Canons Regular of St. Augustin of St. Mary Pré or de Pratis at this town. The church stood within the town wall, between the North Gate on the East, and the river Soar on the West: the attached parish (which by their rule the Friars might not administer) was united chiefly to that of All Saints, perhaps in part to that of St. Nicholas. This transfer of the church may be dated about 1245; for the Friars were certainly at Leicester in 1252.”

Charles James Billson also argued contra the VCH but quoting church historian A. Hamilton-Thompson raised the matter of whether St Clement’s parish survived in any form thus:

“The absorption of St. Clement's church in the Black Friars is a very unusual incident. Mr. A. Hamilton Thompson, although his knowledge of mediaeval ecclesiology is remarkably wide, cannot recall a similar instance. In his opinion, which he kindly allows me to quote, Danet's proposed grant indicates that "if St. Clement's had been given over to the Black Friars, it still had parochial rights, which it would have been difficult to do away with; otherwise the grant would have been made to the Friars themselves. Possibly the nave still belonged to the parish. As regards Friars' churches, however, this arrangement was most unusual; but the Abbey, in granting the church to the friars, could only have surrendered the rectorial tithes and the chancel, and had no power to oust the parishioners from the nave without special agreement. The endowments of the church were very poor. The secular vicar appointed in 1221 had as his stipend merely the daily allowance of a canon in the Abbey, so that it can have been no great sacrifice to the Abbey to part with it. I should not be surprised if the chantry of 1331 was contemplated in order to keep up the parochial services: the normal services in parochial chapels and churches, where there was no vicarage ordained, were frequently called chantries, and were precisely on the same footing."“

The current editors opinion is that the parish and priory church’s were one building based on the following two sets of reasoning:

The Positive Case

Pro Nichols and Billson

- 1. It met the needs of the Abbey, the Parish, and the wider city Church. The Parish Church of St Clement’s was in a state of great poverty at the time of the putative Dominican incardination. From 1221 the Abbey had set up a vicarage and been obliged to pay a stipend of 20 Shillings per annum and grant a corody to both a vicar and a parish clerk keep St Clement’s going - a substantial investment not returned by the likely very low parish rate income and still lower rate of charitable giving. This 1221 act may suggest that St Clement’s was actually running a significant loss (as there were only around 50 people recorded in the whole of West Leicester - including 2 other parishes - and it is unlikely just 15 or 20 rate payers can meet the annual bill of 40 shillings plus expenses the Vicarage needed). Even if the Abbey had not been paying the full 40 shillings but recouped some through rates it was still very likely a money loosing situation. Plus that 40 shillings may not have bought much - as Latin skills were generally poor among the secular clergy, leading to bad liturgical performance, and preaching was either non existent or very poor. As Nichols poetically suggests the arrival of the highly educated and endowment eschewing Friars Preachers in Leicester was an act of God’s providence to meet of the needs of the parishioners of St Clement’s. A more colloquial expression of this point might be “beggars can’t be choosers”. If they could however incardination was a good choice to make in this case. At one stroke it would remove the financial burden of those stipends and corodies; solve a major contemporary problem of questionable education among the parish clergy (in St Clement’s parish at least) supply a large community to maintain the parish liturgy in a far more solemn manner than could be achieved by the vicarage; provide new clergy to the city to take away pastoral, sacramental, and liturgical pressure on the pre-existing communities of Canonical and Secular clergy and with no threat to the career ambitions of those two groups (the mendicants eschewing career advancement in idealism, being mobile and thus ever subject to removal from a particular Priory at short notice, and not generally in the habit of accepting large endowments); finally it would be an opportunity to increase charitable giving in the parish of St Clement if not a raise on parish rates (no longer a concern to the abbey without the advowson anyhow) because these friars would be if nothing else a novelty.

- 2. The Parish Church of St Clement’s was an advowson of Leicester Abbey - an institution founded and endowed by several preceding Earls - making an negotiation of an exchange of (normally sharply defended) advowsons relatively straightforward. The Earl could make life difficult for the canons, and could even potentially expel them from St Mary de Castro’s as Warden of Leicester Castle - he could also argue effectively that predecessors in his title were responsible for all the land, advowsons in Leicester and beyond, and the construction of buildings the canons lived in (either at St Mary de Castro or at Leicester Abbey).

- 3. It was an act of flattery for the abbey to give it and a delight for the Earl. The De Montfort Earls were very literally present at the founding of the order during the Albigensian Crusade, both had met St Dominic, Simon as a child and his father on many occasions, Simons sister was also baptised by the Saint, and one of Simons nephews would join the order. To grant the advowson would be an act of flattery on the part of the Beaumont Earl established Abbey. It would also represent a special act of spiritual and devotion for Simon de Montfort to achieve it.

- 4. The parish shares a dedication with the priory. The obvious contemporary Dominican connections to the shrine in Rome of St Clement (San Clemente al Laterano) were not made until the 17th century. There is no reason to suppose the order would automatically adopt the same dedication of the parish church of the parish they settled in - Leicester Greyfriars conventual church was dedicated to St Mary Magdalene or St Francis of Assisi not St Martin, the patron of the parish they lived in - Leicester Austinfriars chose Katherine as their priory’s patron not the Virgin Mary their parish patron. It might even be surprising for the Blackfriars to make a dedication to the parish patron considering their own recently canonised founder.

- 5. The chantry’s, while potentially a sign of a parishes need according to Thompson (quoted in Billson), are also a sign of an institution favoured by the wealthy benefactors. The Dominicans along with the other mendicant orders

- 6. There is also the 2018 discovery of what is apparently the foundations and graveyard of the Church of St Clement, with bones dating back almost a century prior to the putative Incardination of the Blackfriars, and in the assumed location of the . On balance it seems that the Blackfriars were incardinated in the chancel of the Parish Church of St Clement’s, with the chancel becoming their Priory Church and the Friars the clergy ministering both to the parish while also attending to their work as Dominicans.

- 7. There are 4 excellent written sources supporting it and only one opposed (a questionable source see 3 below).

The Negative case

Contra the Victoria County History (1954 & 1958)

- 1. The VCH makes its objection primarily based on the unusualness of the arrangement. It also referenced Hinnebusch’s provision of three other examples but dismissed his scholarship on the subject. It provides no depth in supporting its argument about irregularity. It also fails to address Hinnebusch’s contra-examples but simply dismisses them without discussion.

- 2. The 1331 Denat Chantry license is quoted as a possible proof against the presence of the Dominicans at St Clement’s because it doesn’t mention them. However, absence of evidence ≠ evidence of absence (logical fallacy in argument) and a chantry established in the nave would not necessarily be in the priory church (see main article, St Clements Church, St Clements after incardination)

- 3. The VCH makes a number of mistakes - the one dealt with in Disputed Question on Location 2 (see next question) suggests the author may not even know the site.

- 3. Point 6. of the positive case holds for a negative point here.

All of the above reasons, for me, outweigh the question of unusualness raised by the one source opposed to the idea that St Clement’s Parish and St Clement’s Priory Blackfriars shared a church.

On 2.1 & 2.2

On the question as to whether the parish church subsisted after Dominican incardination there is division between Billson’s quoted source Thompson and Palmer. First Palmer:

“The church stood within the town wall, between the North Gate on the East, and the river Soar on the West: the attached parish (which by their rule the Friars might not administer) was united chiefly to that of All Saints, perhaps in part to that of St. Nicholas.” - Palmer

Now Hamilton-Thompson quoted by Billson.

“The absorption of St. Clement's church in the Black Friars is a very unusual incident. Mr. A. Hamilton Thompson, although his knowledge of mediaeval ecclesiology is remarkably wide, cannot recall a similar instance. In his opinion, which he kindly allows me to quote, Danet's proposed grant indicates that "if St. Clement's had been given over to the Black Friars, it still had parochial rights, which it would have been difficult to do away with; otherwise the grant would have been made to the Friars themselves. Possibly the nave still belonged to the parish. As regards Friars' churches, however, this arrangement was most unusual; but the Abbey, in granting the church to the friars, could only have surrendered the rectorial tithes and the chancel, and had no power to oust the parishioners from the nave without special agreement. The endowments of the church were very poor. The secular vicar appointed in 1221 had as his stipend merely the daily allowance of a canon in the Abbey, so that it can have been no great sacrifice to the Abbey to part with it. I should not be surprised if the chantry of 1331 was contemplated in order to keep up the parochial services: the normal services in parochial chapels and churches, where there was no vicarage ordained, were frequently called chantries, and were precisely on the same footing."“

It is possible the Blackfriars acted as the parish clergy of St Clement’s - singing their conventual liturgy (consisting of at lest one sung mass as well as seven other sung services every day) in the chancel designated as the Priory Church, to the congregation, listening and watching through the rood screen, in the nave designated as Parish Church for whom the friars conventual liturgy had become the regular schedule of parish services.[11] Such a model had a more extreme precedent in Leicester at St. Mary de Castro, where there were and remain two distinct but united church’s (one conventual, one parochial) in a single building. Historically, the Canons kept their conventual liturgy in St Mary’s (the northern nave and choir of the church for the college of canons and householders of Leicester castle) while the congregation of the Parish of The Holy Trinity had their own parochial church in the larger south aisle, perhaps also coming to listen to the conventual liturgy through the parclose screen dividing the two halves of the church lengthways.

An alternative hypothesis is that the geographical parish of St Clement was completely dissolved upon the gift of the church to the Blackfriars, the land not occupied or owned by the priory directly subsumed into the parishes of All Saints and St Nicholas, as well as any resident in the parish. Although highly unusual and normally apt to spark legal battles with the parishioners who had rights over the nave, the parish population was so small in number and the alternative parish churches so nearby there may have been no opposition. Whatever happened to the geographical parish in the 13th cent it is well documented that either the site of the priory or it’s site including the tiny ancient parish did not fall under any parochial jurisdiction of the Church of England until the late 19th cent, the 1538 parish boundaries never being redrawn.

Until I can find further evidence I will represent both positions.

Further discussion and arguments against my conclusions are welcome.

2. Where was the Priory?

[edit]There are two opinions in sources as to the site of the priory.

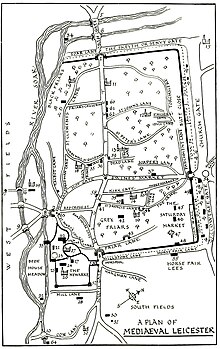

- Blackfriars

- the north of Bead Island or on Frog Island

A previous long standing claim of this article was the the Blackfriars stood on an Island in the River Soar. This claim is to be related to the Victoria County History.[7] Nichols had already dismissed this long standing error in 1795 but here it persists to this day. He stated that the Blackfriars were in the top north west of the old Roman City between the current All Saints Lane and High Cross Street and that the location on an island is the result of a long standing conflation of the Blackfriars (19 on the map below) with Leicester Austin Friary (29on the map below) located on Bede Island North. The current author familiar with both sites considers Bedes position absolutely beyond dispute. It is also confirmed by all existing maps of Medieval Leicester.[12]

Disputed Questions on Foundation

[edit]The origin date of the Blackfriars in Leicester is a contested subject. It is safe to say a priory was established in the 13th cent, during the reign of Henry III (1216-1272), by one of the Earls of Leicester,[7] but beyond this there is much dispute. This divides into three rough areas of controversy. First, who founded the priory? Second, when did the Dominican Friars arrive in the city. Third, when was the priory formally established?

1. Who founded the Priory?

[edit]The founding benefactor of the first Dominican priory at Leicester was one of the Earls of Leicester during the reign of Henry III making it either:

- Simon, the 5th Earl (Earl 1204-1218]]

- Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl (Earl 1229 and 1239-1265: he inherited by law in 1229 but was not ceremonially confirmed until 1239)

- Edmund Crouchback, the 7th Earl (Earl of Leicester 1265-1296)

They were responsible for granting the land, negotiating the advowson of St Clement’s parish with Leicester Abbey, and probably a donation for constructing the Priory

Simon de Montfort, 5th Earl died in 1218 with the first Dominican mission only arriving in England in 1221. This rules him out absolutely.

One source would imply a foundation in 1282 by the 6th Earl.[13] This would be an implausibly late foundation however as Henry III died in 1272. That does not absolutely rule out a Crouchback foundation. However it is very unlikely given Nichols testimony.[14]

The most likely founder was a De Montfort. Simon de Montfort, 5th Earl of Leicester personally met Saint Dominic, the founder of the Blackfriars, in France in 1209 and his daughter was later baptised by him.[15] His son, the famous Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester was also devoted to the order, growing up with story’s of St Dominics miracles and spent time living at Leicester after becoming Earl in 1239. It is therefore highly probable that the priory was established by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester. The famous Leicester historian John Nichols stated it with certainty.[16]

2. & 3. When did the Blackfriars arrive in Leicester and when was the Priory Established?

[edit]The following is a list of possible dates with sources:

Vincent McNabb suggests the Blackfriars were established with a Priory in Leicester by 1233.[19] Another Dominican source places the arrival at 1247.[20] The Victoria County History denies the validity of the pre 1252 date even though it seems to be supported by the signature of Pope Innocent III.[7] The source used to justify the original 1284 dating given in the article can be confidently dismissed since the first documented evidence it based its date on itself assumes an established priory. On balance and given the incorrect opinions of the VCH on the question of St Clement’s it seems safe to assume the priory was established between 1247 and 1254.

Further Disputed Questions

[edit]This will develop around Street Names and possible confusions of date

Controversial & Sensitive Questions

[edit]These fall under two fundamental headings. First, what was the significance of the Albigensian Crusade in the establishment of Leicester Blackfriars? And Second, to what extent are the first records of the Friars Preachers in Leicester coincidental with the 1231 Expulsion of the Jews of Leicester, and is there a wider Dominican role in Simon de Montforts anti semitic pogroms?

1. What is the connection between Leicester Blackfriars and the Albigensian Crusade?

[edit]2. Is there a connection between Leicester Blackfriars and the Expulsion of the Jews?

[edit]In Leicester? If Leicester, first place of expulsion, then in England with the 1275 edict?

| This article is rated Start-class on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

External Sources

[edit]External links

[edit]Archaeological Accounts

[edit]Documentary Accounts

[edit]Contemporary Links

[edit]Source Links

[edit]- ^ https://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/digital/collection/p15407coll6/id/3461

- ^ PARKER, C. F. R. PAPER ON THE BLACKFRIARS OF LEICESTER PRESENTED TO THE LEICESTER ARCHITECTURAL AND ARCHEOLOGICAL SOCIETY L.A.H.S. MAY 28th, 1883| https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Transactions_of_the_Leicestershire_Archi.html?id=8qRCAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y

- ^ https://en.m.wikisource.org/wiki/Mediaeval_Leicester/Chapter_1