Talk:Scale (music)/Archive 2

| This is an archive of past discussions about Scale (music). Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

| Archive 1 | Archive 2 |

Requested move to "Scale (music)"

- The following discussion is an archived discussion of a requested move. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made in a new section on the talk page. No further edits should be made to this section.

The result of the move request was: moved. An interesting case, where both titles comply with different sections of WP:AT. As Powers notes, the title/naming sections of WP:D do exist to supplement WP:AT, but as a widely supported guideline it cannot be completely dismissed and does carry some weight. In the end, I felt the support and oppose arguments were of equal merit – the supporters' consistency argument and the opposers' natural disambiguation argument being the two most compelling cases made – but the clear numerical majority in favour of the proposed title meant there was a consensus to move the article. Jenks24 (talk) 09:56, 25 June 2012 (UTC)

Musical scale → Scale (music) – There has already been considerable support for giving this article a more natural and accessible title. This would bring it into line with most comparable articles among Wikipedia's offerings in music theory: Interval (music), Transposition (music), Degree (music), Organ (music), and so on. The term in each of those is the title of a disambiguation (DAB) page: Interval, Transposition, Degree, Organ; each of these has many meanings, and the solution appears to work very well for the convenience of readers. It is hard to see why Scale (also a DAB page) should be treated anomalously when that term is disambiguated as a core musical topic. People naturally use a search string (whether in Wikipedia itself or on Google, for example) that begins with the specific word "scale", not with the mere background word "musical". There are other arguments in favour of the move, and some can be seen in discussion above. So now let the matter be settled consensually by a wider consultation with editors, toward a robust and lasting solution. NoeticaTea? 11:56, 18 June 2012 (UTC)

- Support. In the discussion above, I proposed this move. Here is a summary of my points:

- Scale (music) is consistent with the style used elsewere in Wikipedia to disambiguate terms such as Scale, Mode, Transposition, or Interval (see list of links provided above). It is impossible to achieve consistency the other way (i.e. by making all titles similar to "Musical scale"), as it would produce in most cases awkward results: e.g., Scale (string instruments) --> String-instrument scale, Scale (album) --> Album "Scale", Scale (descriptive set theory) --> Set-theoretical scale, Scale (map) --> Map scale, Scale (social sciences) --> Social-science scale. For the same reason, Musical mode was recently moved to Mode (music), and everybody in the talk page agreed that this was a necessary ("sensible", "long overdue"...) move.

- The expression "Musical scale" (as well as "Musical notes") is rarely used as a chapter title in music textbooks. The most common titles are "Scales", "Scales and key signatures", "Scales and modes", "Notes, Harmonies & Scales", etc.. See, for instance, Music theory, or musictheory.net, or Music theory and history (web sites are not considered reliable sources, but these titles are commonly used in textbooks as well).

- Consistently with point 2, the introduction says "In music, a scale is...". It does not and should not say "A musical scale is..."...

- In dictionaries, people are used to search for "Scale", not for "Musical scale" when they want to know the meaning of the word scale in music. For instance, see Scale in Webster's online dictionary.

- People searching Wikipedia for an article about musical scales will type at least the specific word "Scale" in the search box. They will not always type "Musical", as it is a much less specific term.

- When you type "Scale" in the search box, a list of suggested titles appears, including "Scale (music)". On the contrary, when you type "Musical", a list appears including articles starting with "Musical", but not "Musical scale". This is because "Musical" is more generic than "Scale", and therefore it is contained in a much larger number of articles.

- Oppose – I'm not sure what Noetica means by "a more natural and accessible title". To me, a title that names a topic clearly without a parenthetical is more natural, and equally accessible. I'd leave it. Paolo's argument's about searching don't make much sense to me either; redirects work great for this kind of thing; as he notes, "Scale (music)" already appears for people who search for it from that direction. Wikipedia:D#Naming the specific topic articles says "1. When there is another term or more complete name (such as Heavy metal music instead of Heavy metal) that is equally clear and is unambiguous, that may be used.". Dicklyon (talk) 15:30, 18 June 2012 (UTC)

- Wikipedia:D#Naming the specific topic articles also says: "If there is a choice between using a short phrase and word with context, such as Mathematical analysis and Analysis (mathematics), there is no hard rule about which is preferred." Paolo.dL (talk) 16:01, 18 June 2012 (UTC)

- Support. While I can sympathise with Dicklyon's "if it ain't broke, don't fix it" position, I find Noetica's argument about consistent treatment with respect to disambiguation pages a convincing demonstration that it is in fact broke.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 17:58, 18 June 2012 (UTC)

- This article was originally named "Scale (music)". On 1 June 2006 Keenan Pepper changed the title to "Musical scale", without previous discussion. "If it ain't broke, don't fix it" applies against this edit, and in support for Noetica's proposal to revert it. Paolo.dL (talk) 19:05, 18 June 2012 (UTC)

- Support —Wahoofive (talk) 18:07, 18 June 2012 (UTC)

- Oppose; natural disambiguation is preferred to parenthetical where available. WP:Disambiguation is a guideline used in supplement to the overriding policy, WP:Article titles. The latter clearly indicates that natural is preferred to parenthetical. If WP:D says otherwise, it is out of date and should be revised to match the policy. Powers T 19:19, 19 June 2012 (UTC)

- Specifically, it's at Wikipedia:Article_titles#Precision_and_disambiguation. For once, we agree. Dicklyon (talk) 19:26, 19 June 2012 (UTC)

- From the same page (WP:Article titles), more exactly from section WP:NAMINGCRITERIA:

- "Article titles are based on what reliable English-language sources refer to the article's subject by."... (see points 2 and 4 in my support statement)

- ..."There will often be several possible alternative titles for any given article; the choice between them is made by consensus."...

- ..."Naturalness – Titles are those that readers are likely to look for or search with"... (see Noetica's proposal and points 4, 5, 6 in my statement)

- ..."Consistency – Titles follow the same pattern as those of similar articles."... (see Noetica's proposal and point 1 in my statement)

- Paolo.dL (talk) 19:50, 19 June 2012 (UTC)

- Those provisions -- particularly "naturalness" -- apply to the base name, not to disambiguation. Only the conciseness criterion (and maybe consistency) would favor "scale" over "musical scale". When it comes to disambiguation, however, the section that Dicklyon linked is the more relevant. Powers T 14:11, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- From the same page (WP:Article titles), more exactly from section WP:NAMINGCRITERIA:

- Specifically, it's at Wikipedia:Article_titles#Precision_and_disambiguation. For once, we agree. Dicklyon (talk) 19:26, 19 June 2012 (UTC)

- Comment on natural versus parenthetic disambiguation. Some commenters above have argued in effect that the present title uses "natural disambiguation", and that this is better because it is preferred by the the main policy page concerned with article titles (WP:TITLE).

My first response is this: most of the provisions of that policy page are contested. In the clear absence of clear consensus for them, it is reasonable not to rely on those provisions alone, but also to appeal directly to the convenience of those looking for Wikipedia articles (by Google searches, internally on Wikipedia, or whatever).

It is also reasonable to appeal to consistency in titles within a broad topic area; and there is no doubt that there is an established practice of disambiguating parenthetically in the articles on music theory. These two considerations are connected: as readers get familiar with the music theory articles, they surely develop expectations about what to search for. If they have seen Degree (music) and Transposition (music), they will expect to find an article called Scale (music).

That is also what they would find at Britannica, by the way. Search at Britannica online with the single word "scale", and the suggestion that heads the list is "scale (music)". (Britannica's article itself is headed simply "scale", with this "lead sentence" following: "scale, in music, any graduated sequence of notes, tones, or intervals dividing what is called an octave.") Similarly on Britannica for "interval" and "key" as search terms, as on Wikipedia.

But to return to "natural disambiguation", the provision at WP:TITLE has this wording:

Natural disambiguation: If it exists, choose a different, alternative name that the subject is also commonly called in English, albeit, [sic] not as commonly as the preferred but ambiguous title (do not, however, use obscure or made up names).

Example: The word "English" commonly refers to either the people or the language. Because of the ambiguity, we use the alternative but still common titles, English language and English people, allowing natural disambiguation.

- I contend that "musical scale" fails as natural disambiguation, so defined. Here are points related to those Paolo has made, above:

- Other encyclopedias (like Britannica) do not use it; dictionaries (I checked five) do not have "musical scale" as a lemma: they just use "scale", and define it for various contexts. It simply is not what a scale is "commonly called in English", even though it is sometimes used in running text to avoid ambiguity.

- "Musical scale" is itself ambiguous. It has other meanings, such as in these excerpts that I quickly found through Googlebooks searches:

- "The first two scenes of Act III perform a similar function, but on a yet grander musical scale."

- "... a profoundly ironic adaptation of Wagner's idea of interior drama on an ambitious musical scale, ..."

- "... wanted to do some dramatic work on a larger musical scale ..."

- "However much the social scale has subordinated women in life, the musical scale has allowed operatic heroines to remain securely on top." [Exact meaning?]

- "... on a bigger musical scale than those of the seventeenth century. Something had to be done if the opera was not to last all night."

- "All three sets were stunning examples of verismo suitably romanticised to Puccini's musical scale and scope."

- The example given at WP:TITLE is quite different in form and prevalence: "English language" versus "English people". (We could add "English opening" too, which is called simply "the English" by chess buffs.) In these, the term to be naturally disambiguated comes first, so that searching is still natural also. Not so with "musical scale".

- As I suggested in introducing this RM, people enquiring after an article on musical notes, or transposition, or interval, or organ do not have the term "musical" at front of mind. That is already understood. For the present at least, they lack interest in, or knowledge of, other uses of "note", "transposition", "interval", or "organ". It is our job in determining titles to be aware of this. We (right now, in this discussion) have an overview of all the meanings; they cannot be expected to. It is often difficult to see things from the readers' point of view; but it is essential for us to do so in making a work or reference like Wikipedia: in our writing, our editing, our design of the framework in which we present information to readers, and – no less certainly – in the titles that we give our articles. What is "natural" for us is often quite artificial for readers, and quite unhelpful. Conversely, the use of parenthetical disambiguation is quite familiar – quite natural – to most readers. Everyone knows perfectly well what Scale (music) will be about.

- In this case, I say Britannica and the dictionaries have it right; and we have it right for most of our music theory articles. Why not for this one? ☺?

- NoeticaTea? 09:12, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- "even though it is sometimes used in running text to avoid ambiguity." Precisely! And in fact, our article titling policy explicitly prefers "natural" disambiguation -- that is, of the sort one would find in running text. Powers T 18:12, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- Support per

Noetica'sPaolo's points 1, 2, 4, and 5. As long as Musical scale redirects to the new title, I don't see why not. While I don't think it matters much either way, consistency is a worthy goal. Rivertorch (talk) 00:14, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- Fine, Rivertorch. Note that those numbered points are Paolo's, not mine. ☺ NoeticaTea? 01:06, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- So they are. Thanks for pointing this out. (And thanks to Paolo for writing good points!) Rivertorch (talk) 05:25, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- Fine, Rivertorch. Note that those numbered points are Paolo's, not mine. ☺ NoeticaTea? 01:06, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- Support Scale (music). In the flow of speech or writing, "musical scale" is a perfectly acceptable ad hoc disambiguation. As the subject title for an encyclopedia article, the parenthetic form seems more appropriate. __ Just plain Bill (talk) 00:51, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- Support Scale (music), as already expressed in preceding section. −Woodstone (talk) 02:59, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- I hate all the parentheses in general, so I'm biased. This doesn't seem like a particularly bad example at all, so renaming it would be fine. —Keenan Pepper 07:10, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- Just a dream . I do not like parentheses either. I'd rather disambiguate by adding a path such as that used to show the position of a web page or file within a website or File system. For instance: Music → Scale (a better format, which I cannot reproduce, is used in the path bar of Windows Explorer in Windows 7). However, this would require a modification of the Mediawiki interface. Disambiguation would be obtained by simply assigning a cathegory (such as "Music") to an article. The path would appear automatically before the title, only if needed to disambiguate. This is similar to what we typically do in the first sentence of most Wikipedia articles (see point 3 in my support statement above). It requires a modification in Mediawiki because it implies that, when you type "Scale" in Wikipedia's search box, the context menu will show, for instance, the following items:

- Music → Scale

- String instruments → Scale

- Album → Scale

- Descriptive set theory → Scale

- Scale ratio (in this case, "Ratio → Scale" is not appropriate)

- Cartography → Scale

- Social sciences → Scale

- Geography → Scale = Metereology → Scale = Astronomy → Scale, etc. (same meaning in different contexts)

- The article title, and each of the items in the search box menu would not need to show the whole path, but only the minimum number of cathegories needed for disambiguating (typically, just one). For instance, "String instruments → Scale" is enough for differentiating the scale of string instruments from other scales, although the complete path would be "Music → Instruments → String instruments → Scale". If a title does not require disambiguation, its path will not be shown at all. For instance, Johann Sebastian Bach is enough to indicate a specific article, although its complete path (or one of the many possible ones pointing to the same article) would be "Music → Composers → Johann Sebastian Bach".

- This is currently just a dream. Mediawiki can be modified, but not in a short time. In the meantime, we can speed up the process by adopting the only method currently available to disambiguate by means of cathegories, i.e., by supporting Noetica's request.

- Paolo.dL (talk) 08:45, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- Just a dream . I do not like parentheses either. I'd rather disambiguate by adding a path such as that used to show the position of a web page or file within a website or File system. For instance: Music → Scale (a better format, which I cannot reproduce, is used in the path bar of Windows Explorer in Windows 7). However, this would require a modification of the Mediawiki interface. Disambiguation would be obtained by simply assigning a cathegory (such as "Music") to an article. The path would appear automatically before the title, only if needed to disambiguate. This is similar to what we typically do in the first sentence of most Wikipedia articles (see point 3 in my support statement above). It requires a modification in Mediawiki because it implies that, when you type "Scale" in Wikipedia's search box, the context menu will show, for instance, the following items:

- Support, per Noetica and Paolo. Neotarf (talk) 12:50, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- Oppose either title is fine. If it's not broke, we don't need to fix it. ---Kvng (talk) 22:19, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

- I am a bit confused. According to your premise, either you are neutral, or you should also oppose the move which in 2006 substituted the original title (Scale (music)) with the current one (Musical scale)... Paolo.dL (talk) 12:45, 22 June 2012 (UTC)

- The above discussion is preserved as an archive of a requested move. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made in a new section on this talk page. No further edits should be made to this section.

You must be Kidding

This is one of the worst articles in wikipedia that I have seen. Why can't musicians make any damn sense when speaking in English instead of music?

The very first sentence is incorrect. A musical scale is not a succession of "notes." It is a set of tones each having a definite pitch and at a specific interval relative to all the other pitches, played in a sequence that either rising or falling in frequency. A note is the written or spoken name you give to a pitch. It is not the pitch itself. A scale, however, is about the pitches, not about their names.

"Composers often transform musical patterns by moving every note in the pattern by a constant number of scale steps: thus, in the C major scale, the pattern C-D-E might be shifted up a single scale step to become D-E-F. Since the steps of a scale can have various sizes, this process introduces subtle melodic and harmonic variation into the music. "

That makes no sense whatsoever. Composers choose sequences of pitches (melody) and combinations of pitches harmony. They may sequence or combine pitches of any way they want, and jump from one pitch to another or slowly change the pitch of a sound (not a note, you cannot change the pitch of a note, a note is what you use to designate a pitch, it is not he pitch itself.

Think, man. Don't just open your mouth and let words drop out.--Nomenclator 12:20, 26 December 2006 (UTC)

Common, really, what do you mean by "provides material for part or all of a musical work." Sort of like trees provide material for making furniture, pigments and solvents provide material for painting pictures, and scales provide material for making music? No! Music is made of sound, not material. Sound is energy not material. The materials used for making music are the materials that are used for making musical instruments. --Nomenclator 02:55, 27 December 2006 (UTC)

- Several responses:

- I don't think that it's at all self-evident that scales are composed of pitches. The sequence C - E-double-flat - E - E-sharp - G-A-B-C isn't a scale, even though it might enharmonically sound like one when played (on some instruments). In fact, a C major scale will sound at a different pitch when played on a transposing instrument; players of such instruments routinely refer to notes (and scales) by their written names.

- Nomenclator is right that composers and musicians don't start with theoretical constructs and make music with them. Music comes first and theory follows after. The quoted passage is certainly dreadful and needs revising. However, musicians commonly use the word note to refer to sounding pitches; much as we'd like to make a distinction between written notes and pitches, it isn't standard English.

- As for why musicians can't make music theory concepts easy to understand (a complaint voiced on a number of pages): we all learn a simplified version of music theory from Mrs. Grundy, our third-grade piano teachers. As we become serious musicians, we learn that even the most fundamental aspects of music theory (such as what is a half step) aren't as simple as Mrs. Grundy pretended. It's like physicists learning that the theory of relativity totally makes wrong everything they learned about Newtonian mechanics, except that instead of requiring esoteric experiments to tell the difference, it's easy to perceive in Indian music, jazz, or Baroque theory treatises if you know what to look for. In all these articles we have to balance between a simplistic explanation which is useful for beginners, and a more sophisticated understanding which is necessary for a variety of styles of music, including non-Western music. It isn't that easy.

- —Wahoofive (talk) 23:39, 29 December 2006 (UTC)

- Whoever wrote this initial comment is mistaken. The distinction between "note" and "tone" is the author's own, and is not a standard piece of music-theoretical terminology. Furthermore, Wahoofive's comment that "musicians don't start with theoretical constructs and make music with them" is also incorrect. Explicit instruction in theoretical concepts, including scales, has been part of musical education for centuries. Njarl 23:33, 21 March 2007 (UTC)

As for "...musicians don't start with theoretical constructs and make music with them. Music comes first and theory follows after." That's not strictly true. I'm an (amature) composer in various styles and most of my work starts from a theoretical basis. (I'm kinda' left brain focused.) Also, the name of this section is nigh unto useless and perhaps should be changed. Karatorian (talk) 03:56, 7 October 2012 (UTC)

Derived

Anyone know anything about derived scales formerly mentioned in the article? Looking around I find mention of modes being derived from the major scale but no mention of "derived scale" as a term. Hyacinth 09:43, 4 December 2005 (UTC)

- See http://www.outsideshore.com/primer/primer/ms-primer-4-6.html for one (jazz) usage of the term. yoyo 07:44, 17 March 2006 (UTC)

I associate the term "derived scale". with the term "synthetic scale." Examples of synthetic scales are anhemitonic pentatonic (aka "black keys" pentatonic), whole tone, hexatonic, and octatonic--all scales that are not found in common-practice tonal repertoire. It may be that "derived" and "synthetic" scales are related--yoyo's link makes me think so.Blap Splapf (talk) 00:12, 14 November 2012 (UTC)

New intro

Just re-wrote the intro. Expect it to be instantly reverted, but hope the article can be rewritten in this spirit, to make it comprehensible to non-geeks. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 213.207.137.140 (talk) 20:30, 24 March 2014 (UTC)

Introduction is self-contradictory

Sorry but...

Is there a reference for the premise that 'Scales differ from modes in that scales do not have a primary or "tonic" note'?

When I was a kid, I learnt how to make a major scale. Starting from some note, I first go up two semitones, then another two, then one, then two... So how should I think of that first note, if not as a primary or "tonic" note?

Later in the article, mention is made of different accepted usages of the word "scale". I guess that this statement in the intro is specific to one rather obscure usage? Or is it just plain wrong?

In its current form, it seems to be contradictory to, shortly thereafter, the mention of the 'C major scale', for which, surely "C" has some kind of significance which none of the other notes in that scale enjoys.

I see in this discussion history that this point has been raised before. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 58.3.81.22 (talk) 14:02, 2 July 2008 (UTC)

- It's because "scale" is sometimes used to mean "mode". In the strict sense, a "scale" is a set of notes in a certain order (you can think of them as being arranged around a circle). When people talk about the "C major scale", "C" specifies the tonic and "major" specifies the mode (also called Ionian). So strictly speaking it should be "C major mode". The scale in this case is the diatonic scale which includes the note C (but C is not strictly more important than any other note).

- So the strictest sense, 'Scales differ from modes in that scales do not have a primary or "tonic" note', is not the only meaning. Some may argue that the term is misused (much like physicists tell us that me misuse the term "weight"). I prefer to just say there are different (though related) meanings. —Celtic Minstrel (talk • contribs) 14:22, 2 July 2008 (UTC)

- That's beyond pendantic, Minstrel. A C major scale has no tonic note? Every musician calls a C major scale a C major scale; none would say they're going to warm up by practicing a few "modes". No one except a few crackpot theorists would say that "scale" means exclusively what you say. Scales ha So saying a piece is in "C major" might mean the same thing as "C major mode", but "scale" is something different. —Wahoofive (talk) 06:06, 4 July 2008 (UTC)

- 'Scales have the notes in order, but a mode need not.'? Um... that doesn't sound right. On the other hand, the reverse (modes have the notes in order, but a scale need not.) sounds wrong too. I think it's better to just say they are both ordered. A scale is a group of notes arranged around a circle, and a mode is when you break the circle and stretch it out into a line. Both are ordered, but the scale doesn't have a designated "first" note. (But one can make an exception for "major scale" and "minor scale", treating them as modes, because that's the normal terminology.) —Celtic Minstrel (talk • contribs) 03:29, 15 November 2008 (UTC)

- That's beyond pendantic, Minstrel. A C major scale has no tonic note? Every musician calls a C major scale a C major scale; none would say they're going to warm up by practicing a few "modes". No one except a few crackpot theorists would say that "scale" means exclusively what you say. Scales ha So saying a piece is in "C major" might mean the same thing as "C major mode", but "scale" is something different. —Wahoofive (talk) 06:06, 4 July 2008 (UTC)

- This happens a lot on Wikipedia. Different editors bring different definitions of terms with the same spelling to the table from the general culture, and argue over which meaning is correct, when what they should do is realized that both meanings are in use in the culture, and collect and distinguish those meanings in the article. One meaning of "scale" is a collection of notes with no tonic (such as some people describe the Diatonic Scale) from which other "scales" that do have tonics are derived (such as the Major scale and the Minor scale). Those derived tonic-having scales are necessarily also modes of each other, precisely because they represent the application of the tonic to each of the members of the master non-tonic scale. Modes are scales too, and they have tonics, but they are called modes to point out their relationship to one another. All modes are equal, but are sometimes sloppily presented as if they are not equal. For example, the Ionian Mode (another name for the Major Scale) can be presented as generating the other modes, such as the Aolian Mode (another name for the Minor Scale), but it's just as easy to generate all the other modes from any of the modes, even from the attention-starved sibling, the Locrian Mode. The meaning of "scale" that includes a tonic is probably used more often than the meaning of "scale" that doesn't include a tonic, but that doesn't mean one meaning displaces the other or that only one meaning is correct. Both meanings are valid and in use. They are actually different terms with the same spelling, and they should be carefully and clearly distinguished in the article. Anytime you see a note name associated with a scale, such as "C Major Scale", you definitely know there's a tonic, but if no note name is included, it doesn't necessarily mean there's no tonic. For example "Major Scale" describes an intervalic relationship, or scale shape, without pinning it to any particular location in real pitch space, yet it still reserves the fact that one of the members is taken to be the tonic. That's actually a third meaning of scale that should be distinguished--it's that thing that is common to all transpositions of the same shape in real pitch space. C Major Scale and D Major Scale are both "Major Scales", so "Major Scale" is a logical level above them, or a step more abstract than they are, and should be distinguished. The Chromatic Scale is sometimes meant as having no tonic, representing the even playing field of the total pitch resources of the 12EDO or 12TET tuning system, but it's sometimes also meant as having a tonic. For example, as that scale that represents all the possible pitches you can play in a given key, as long as you use the right melodic tactics. It's also the scale that represents all the possible pitches you can play over a given chord with the right tactics. Hm, that's another meaning of scale, one that has a root instead of a tonic. Explaining: In jazz, a so-called "chord scale" is associated with the chord of the moment, which is not necessarily the tonic chord of the key, and yet one of it's members has a tonic-like function for the duration of the chord, which is the scale member that is the root of the chord. For example, the G Bebop Dominant Scale has a root of G, even though G7 ultimately implies the key of C or a tonic of C. 108.60.216.202 (talk) 03:36, 26 April 2015 (UTC)

Definition - does a scale have to be ordered?

Current definition:

- "In music, a scale is any set of musical notes ordered in an ascending or descending sequence."

Questions:

- Does a set of notes have to be ordered to be a scale?

- Does a set of notes have to have a particular temporal sequence to be a scale?

If we consider a scale as a set of pitches (or pitch classes), e.g. {A, B, C, D, E, F, G}, there is no specific ordering. If we specify one pitch to be the tonic, then we have introduced an order. But does a musical scale have to specify a tonic?

If we consider a scale as a set of notes that can be played in a temporal sequence, then if we specify the sequence, we have introduced an order. But does a musical scale have to specify a temporal sequence? Isn't {A, B, C, D, E, F, G} a musical scale regardless of what sequence the notes might be played in?

Webrobate (talk) 05:30, 28 December 2012 (UTC)

- You seem to be using a narrow definition of "ordering", making this equivalent to "performing sequence". By definition (as given in this article), a scale views the notes within a set with respect to pitch height. This is conventionally described as "order". If one chooses to play the notes in that sequence (low to high, or the reverse), we usually say the performer is playing "a scale", or is playing "in scale order"; if one chooses to play in some other order, then "scalewise" does not apply. Does that help?—Jerome Kohl (talk) 06:54, 28 December 2012 (UTC)

- A scale is an ordered set of notes. They are ordered by pitch (or fundamental frequency), and the order may be either ascending or descending. The term "scale" comes from Latin "scala", which means "stair" (this is the reason why one of the meanings of the verb "scale" is "climb over"). The expressions "scale step", "whole step", "half step" are consistent with this etymology of the term scale. If the scale were not an ordered set, it would not be possible to define scale steps (first, second, third...). Also, it would not be possible to define interval numbers (unison, second, third, ...). The natural notes are named A, B, C, ... so that when they are in "scale order" (i.e., ordered by pitch) they are also in alphabetic order (the alphabet is an ordered set of letters). Paolo.dL (talk) 08:55, 28 December 2012 (UTC)

- It needs to be said for clarification, that even when a scale is illustrated in sequence of descending pitch, its members are still identified numerically in ascending sequence. For example, in the ascending and descending forms of the melodic minor scale, the sixth and seventh scale degrees take different pitches. We can make that statement because they have not taken different numerical identities as numbered scale members. In other words, they are still considered the sixth and seventh scale degrees, counting from the bottom up, even when the scale is notated in pitch sequence from the top down. 108.60.216.202 (talk) 03:23, 2 May 2015 (UTC)

Scales and pitch

"A single scale can be manifested at many different pitch levels. For example, a C major scale can be started at C4 (middle C; see scientific pitch notation) and ascending an octave to C5; or it could be started at C6, ascending an octave to C7. As long as all the notes can be played, the octave they take on can be altered."

The text above, which is the entire content of the "Scales and pitch" section, has a problem. I'd like to just gut the whole section, but moves like that usually get reverted, so I'll discuss it here first. Here's why I don't like it: It confuses the term "scale" in music theory, commonly meaning a collection of pitch classes with one of them being designated tonic, with the term "scale" meaning a finger exercise in piano instruction (like "practice your scales and arpeggios daily"). An octave-repeating scale in music theory is implicitly understood to continue indefinitely in both directions (even beyond the range of hearing) and contain all of those pitches. Theory books find it convenient to illustrate a scale by notating its members with each pitch class represented once and arranged low to high, except the tonic, which is usually shown repeated at the octave. Unfortunately, they don't explicitly state "and continuing in both directions indefinitely", which could allow novices to misinterpret a scale as being the same as that written example. It's actually unnecessary to write the repeated tonic at the octave in order to completely define an octave-repeating scale. A C major scale can be completely defined by writing 7 notes, not 8, because it only contains 7 pitch classes. Writing 8 is just a convention (probably to avoid the discomfort of "hanging on the leading tone" for anyone who is sight singing along while they're reading the theory book). The second tonic shown in book illustrations has nothing to do with the definition of "scale" in music theory. The one-octave snippet typical in book illustrations has nothing to do with scale theory. A scale doesn't begin and end at tonic delimiters. Finger exercises called "scales" do typically begin on the tonic, reverse direction at the tonic in a different octave, and end on the tonic again. But that meaning of scale (as an exercise) is different than the theoretical meaning of scale that most of this article is describing. Just like an arpeggio (exercise) is not the same as a "chord" (music theory), even though an arpeggio is composed of chord tones, so a scale (exercise) is not the same as a scale (music theory), even though the exercise is composed of scale members (music theory).

Maybe, instead of deleting this section, it should be rewritten to say that "scale" has another meaning in music, which is a type of finger exercise? 108.60.216.202 (talk) 01:50, 26 April 2015 (UTC)

Non Intelligibility as an interested non specialist,looking to gain some understanding of music. i got none. the whole article is more or less gobbledygook to someone with no prior knowledge. is this a function of the editing process where experts have added and subtracted their edits over time allowing the whole article to drift into a zone where only these experts can enter.. is there a process where articles can be examined, not for exactitude or fulsomeness, but for common sense, to deliver up articles that non- speicialists can benefit from. perhaps a prologue? Daiyounger (talk) 20:42, 1 April 2016 (UTC)

differential scale, ordinal scale, rational scale

The terms differential scale, ordinal scale, and rational scale came from a music theory book by a famous composer that I read, but I only saw it in one library a long time ago, and I don't remember the book title or composer's name. Does anyone else recognize this and can you point me to it so I can get the references before adding them to the article? The terms describe very basic abstract differences in the way we catalog collections of sounds used as a compositional resource to draw from. A differential scale is any collection of sounds that we can tell apart, for example, trash percussion (one bottle, one can, one brake drum, etc.), or tape loops, or sound effect samples. An ordinal scale adds a level of information in that there is something about the sounds that allows us to order them, such as brightness. A rational scale adds the next level of information that allows us to determine the relative spacing between the members of an ordinal scale. If the exact brightness of the cymbals could be measured and prescribed, one could make a rational scale of cymbals. This is the realm of what most people know as pitched scales, where Hz can be used to determine the exact spacing and relation to an absolute reference. All of the various theories determining tuning, and cultural preferences for scale membership belong under the umbrella of "rational scale". It may also be appropriate to call the collection of related durations used in a composition or portion of a composition a type of rational scale, which connects to the idea of temporal or metrical modulation. I will have to find the book to be sure. There is a slight confounding or confusion problem in the terminology in that rational scale doesn't imply that the relationships must be rational in the mathematical sense (capable of being expressed as whole-numbered ratios); scale derivations using mathematically irrational numbers (such as the 12th root of 2) are still called rational scales in this musical scale categorization terminology. -- Another Stickler (talk) 19:45, 8 December 2008 (UTC)

- This use of the term "scale" (although etymologically related) doesn't really have anything to do with music scales.The article Level of measurement addresses this topic. —Wahoofive (talk) 05:52, 9 December 2008 (UTC)

- Actually, yes, it absolutely does have to do with music and even with the musical scales in this article. The book was written by a well known 20th century composer (unfortunately I can't remember which composer, but the book was in the USC library music racks in the 1980s with all the other composition and theory books I was reading at the time, which you could do as a non-enrolled student as long as you showed ID and read them on the premises, as UCLA and CSULB also allowed), and it's easy to recognize them in musical contexts. Thanks, the Level of measurement article is indeed similar, but not exact. I would bet the ideas of Stanley Smith Stevens influenced that composer. Also, if I remember right, the composer only included three scales in his theory, while the article describes four, including an "interval scale" which has degree of difference but not ratio of difference. It makes sense to leave that one out of music theory, because it has no musical example. In music, once you get degree of difference, you automatically also get ratio of difference, because degree of difference is measured in pitch, which is a function of frequency, and frequencies can be compared exactly. You can indeed say "this frequency is twice that frequency." These three scales are actually a logical level above what's being described so far in this article. I guess these are more like classes or types, because all of the scales described in this article so far would fall under the single class of rational scales, because they incorporate pitch, but rational isn't the only class. The other classes have musical examples as well. Take for instance a set of tom toms arranged high to low but not required to have an exact tuning. That's obviously an ordinal scale. I'll find that book again some day! Please, if anyone else finds it first, help contribute. (Another Stickler on a different computer years later) 108.60.216.202 (talk) 00:55, 26 April 2015 (UTC)

- Ben Johnston discusses the musical applications of Stevens's four scales of measurement in his 1963 article "Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource."[1] This was, if I'm not mistaken, the first music theory article to invoke that concept, but the idea resurfaces in some of Johnston's subsequent writings (all of which appear in Maximum Clarity)[2] and in Milton Babbitt's 1969 lecture "Contemporary Music Composition and Music Theory as Contemporary Intellectual History." [3] Despite the great value Stevens's scales of measurement may have for theorists, I cannot see how this concept would fall inside the scope of an article for nonspecialists.Chuckerbutty (talk) 17:53, 13 December 2016 (UTC)

References

- ^ Johnston, Ben. "Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource": Perspectives of New Music 2 no.2 (Spring-Summer 1964), 56-76

- ^ Johnston, Ben. "Maximum Clarity" and Other Writings on Music. Edited with an introduction by Bob Gilmore. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

- ^ Babbitt, Milton. "Contemporary Music Composition and Music Theory as Contemporary Intellectual History," inPerspectives in Musicology. Edited by Barry S. Brook, Edward O.D. Downes, and Sherman Van Solkema. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1972.

Jazz and blues

Is that right, the pitch of a saxophone may be bent on the fly? Mouselb (talk) 19:39, 22 November 2017 (UTC)

Sad and happy

It would be good if this article made it clearer that minor keys sound sad and major keys sound happy. Vorbee (talk) 21:17, 4 December 2017 (UTC)

- It's not universally clear, though. There are counter-examples both ways. But the article Major and minor agrees with you: "... and 'music based on minor scales tends to' be considered to 'sound serious or melancholic'." -- Michael Bednarek (talk) 05:42, 5 December 2017 (UTC)

Question

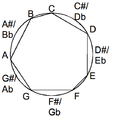

I know nothing about music, but noticed that the distance between notes on the "Diatonic scale in the chromatic circle" pictured in this article didn't look correctly proportioned. Is this an improvement? If not why not? :)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diatonic_scale_over_360_degrees.jpg — Preceding unsigned comment added by Hazratio (talk • contribs) 23:26, 8 February 2018 (UTC)

- I do not understand your diagram. What do the tick marks represent? Musically, the intervals between C/D, D/E, F/G, G/A, and A/B are pretty much the same. In equal temperament those intervals are all 200 cents on a circle of 1200 cents. In your circle, they range from 45° to 75°. E/F and B/C are 100 cents apart, or half steps, which could be represented as 30° arcs. Just plain Bill (talk) 00:21, 9 February 2018 (UTC)

- As Just plain Bill wrote, the ratio, in cents, can simply be shown in 30 degree arcs, and your graph doesn't do that. -- Michael Bednarek (talk) 03:31, 9 February 2018 (UTC)

- I, too, do not see the logic. According to your chart the intervals between B–C and C–D are the same (both 45° arcs), whereas the first (a semitone) should be only half the second (a whole tone).—Jerome Kohl (talk) 03:54, 9 February 2018 (UTC)

- [begin Hazratio's reply] My image is based on the discussion of the musical scale as it relates to "The Law of Seven" as expressed by Boris Mouravieff in Volume I of his "Gnosis" trilogy (see link, below). Mouravieff writes:

- I, too, do not see the logic. According to your chart the intervals between B–C and C–D are the same (both 45° arcs), whereas the first (a semitone) should be only half the second (a whole tone).—Jerome Kohl (talk) 03:54, 9 February 2018 (UTC)

- As Just plain Bill wrote, the ratio, in cents, can simply be shown in 30 degree arcs, and your graph doesn't do that. -- Michael Bednarek (talk) 03:31, 9 February 2018 (UTC)

- "We will now look at the action of the Law of Seven, in movements in which vibrations increase. In this case, the consecutive deviations we have spoken of at the beginning of this chapter will create a discontinuity. This discontinuity intervenes in the propagation of all movements, though they can and do seem to us progressive and uninterrupted. In this context, let us examine the musical octave, whose structure perfectly reflects the Law of Seven. By octave, we mean the doubling of vibrations. The musical scale is located between the limits of an octave, and comprises seven tones and five half-tones. The missing half-tones are positioned as indicated by the arrows in the following figure:

- [see page 88 of the PDF file linked to below].

- "The first is found between the notes MI and FA, and the other between SI and DO . Let us now see the way the vibrations progress, which, as we have said, occurs discontinuously. The following diagrams show this discontinuity, expressed in fractions and whole numbers on the one hand, and in the curve of discontinuity of a musical octave, on the other (Gnosis, Vol. 1, Page 88).

- One of his diagrams show the missing half-tones on a linear scale and the other one relates the following fractions to the tones on the scale:

- DO 1, RE 9/8, MI 5/4, FA 4/3, SOL 3/2, LA 5/3, SI 15/8, D0 2

- I'm just trying to understand the significance of this musical illustrations to the esoteric "Law of Seven" originally articulated by Gurdjieff and his student Ouspensky. Perhaps they are using a different scale? I found this elsewhere on Wikipedia:

- " It should be noted that the musical scale Gurdjieff is quoted as using [11] is not the modern standard musical scale but Ptolemy's intense diatonic scale, a just intonation scale associated with the Renaissance composer and musical theorist Gioseffo Zarlino."

- Perhaps that is the scale Mouravieff has in mind, too? I would appreciate any input you musicians care to shed on this.

- Here is the link to the PDF file of Gnosis, Vol. 1:

- http://www.gornahoor.net/library/mouravieff1.pdf [end Hazratio's reply] — Preceding unsigned comment added by Hazratio (talk • contribs) 00:34, 10 February 2018 (UTC)

Thanks for linking that. It looks like the scale in Fig. 34 on p. 88 is a five-limit diatonic scale, whose notes differ from those of an equal-tempered scale by amounts varying from a few cents up to fourteen or sixteen cents. Those might seem like slight differences when drawn on a chromatic circle, but they can be audible, depending on the musical context in which they appear.

The spacing between notes of a tempered diatonic major scale, expressed in cents, is 200, 200, 100, 200, 200, 200, 100, for a total of 1200 cents between the first note (the tonic) and its octave. As seen in the gallery below, the spacings between C-F and G-C form similar patterns, or tetrachords.

A diatonic major scale is simply the "doe, a deer" scale that Julie Andrews taught the von Trapp kids in "The Sound of Music," widely known, and nothing particularly esoteric. I have heard the father of an Indian violin student sing the same scale as "Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni Sa."

-

Major scale in chromatic circle

-

Enneagram as octave

The enneagram presentation may connect the notes of a scale to something, but I'm not sure what practical use it would be to a musician. Just plain Bill (talk) 01:55, 10 February 2018 (UTC)

[begin Hazratio reply] Thanks... I revised my image a bit (added the fractional proportions and the "DO, RE, ME" labels). One last question: If my image does accurately illustrate the intervals (?) between the notes on Mouravieff's scale, are the intervals between the notes in the image that I was questioning accurately represented? (i.e. is the image in the article proportional in the same way mine is?) Thanks again--I appreciate your patience! :)

p.s. See also: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diatonic_scale#Tuning [end Hazratio's reply] — Preceding unsigned comment added by Hazratio (talk • contribs)

- Your image seems to show proportions based on frequency, while musical pitch is a human perception, more or less logarithmically related to frequency. Just plain Bill (talk) 03:08, 10 February 2018 (UTC)

Include Some Very Basic Information

Shouldn't this article at least name the notes on the scale for easy reference? Like a one minute grade one music reading class? Can someone show us Every Good Boy Deserves Favor and FACE? And what about those lines that represent all the bass notes? Can someone show us which notes went where? It seems like this Wikipedia article would be the place to include such very basic information. Thanks.LFlagg (talk) 01:07, 22 July 2018 (UTC)

- I'm not quite sure what you mean, but it sounds like you are asking for some instruction in music notation to be included here. This article does seem to be assuming that the reader will know how to read the treble-clef examples, and there is a separate article on music notation elsewhere on Wikipedia. What I don't understand, though, is what you mean by "those lines that represent all the bass notes", and "which notes went where". I don't see any "bass notes" mentioned or illustrated in this article, and the positions of notes relative to each other seem to be explained very clearly. Could you give some quotations from the article that seem not to clearly present answers to your questions?—Jerome Kohl (talk) 01:25, 22 July 2018 (UTC)

- If there is a Wikipedia article that covers basic information about the notes on the musical scale, both above and below middle C, I would like to see it. Please excuse me. I was using Wikipedia as my primary source of information and neglected to google, "How do I read music?"LFlagg (talk) 01:57, 22 July 2018 (UTC)

The Definition

Are Major Diatonic beginning on C and Major Diatonic beginning on F different scales?

The definition "... a scale is any set of musical notes ordered by fundamental frequency or pitch." would seem (to me) to imply that they are different. However, in colloquial use, it seems (to me) that people focus on the interval *relationship* between the tones, not the absolute pitches. They think of "Diatonic Major" as a scale, regardless of the tonic. That's the way many of the Wikipedia articles on specific scales seem to be organized. Yes, there are some cultures where some scales are only played from a specified root, but I'm thinking that predominant use relates to intervallic relationships, not absolute pitches.

Also, the phrase "musical notes" in the definition of "scale" brings in the concept of duration ("... a note is the pitch and duration of a sound, and also its representation in musical notation ..." from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musical_note). Should scales really incorporate duration. Should they involve "representation in musical notation"?

I love the approach of explaining something by giving a concrete example ... "Here's the Major Diatonic scale starting on middle C" ... and then progressing to a more general understanding of the "Major Diatonic scale" and then generalizing to "scale". In this situation, the concrete examples at the start of the article - "The C major scale" and "The A minor melodic minor scale" - seem to be driving the definition of "scale".

Wikipedia has many articles on scales. We have https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C_major, which begins "C major (or the key of C) is a major scale based on C, ..." and links to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Major_scale, which beings "The major scale (or Ionian scale) is one ...". These two articles might be terms (just for this discussion) examples of a "fixed scale" and a "relative scale". Both are scales, but the current definition of scale ("... set of musical notes ...") limits us to fixed scales.

Scala by Manuel Op de Coul (http://www.huygens-fokker.org/scala/) avoids the issue by using the term "Musical Modes" for relative scales (see http://www.huygens-fokker.org/docs/modename.html ... currently 2,750 modes). However, even Manuel points out that "Mode" is a horribly overloaded term.

−ClintGoss (talk) 11:58, 20 November 2018 (UTC)

- As often in language, as opposed to science, terms are loosely defined. The same word can have different meanings depending on context. One very common usage is in the phrase "practising scales", where obviously not the "relative" definition is meant. Perhaps that is the one the article should focus on. Indeed as remarked, a scale is an ascending or descending sequence of pitches, rather than "notes". −Woodstone (talk) 15:00, 20 November 2018 (UTC)

- Thanks for weighing in Woodstone! I'm not trying to be argumentative here ... just trying to use some thought experiments to test what is meant by "scale".

- If I am practicing a scale on my "G flute" (with a fundamental of G), and I then move to my "C flute", am I practicing a different scale? Not to my mind. I'm using the same fingerings, and getting the same "feel" from the scale. It is exactly the relative definition that I'm thinking.

- If I'm playing guitar for a while and it goes flat, I am playing different pitches, am I playing a different scale?

- If I move from my 12TET G flute to my Just Intoned G flute (yes, I really do have both of these ... by the same flute maker) I am using the same fingerings, but the scale does indeed sound different (it is certainly noticable!). If feel that I am actually playing a different scale.

- This leads me to think that the pitch relationships are what is key in the scale. If a scale is defined in terms of a degrees of some musical temperament, then the temperament must be part of the definition of the scale - much more strongly than the root tone that I choose. −ClintGoss (talk) 17:12, 20 November 2018 (UTC)

- The definition you chose for "note" (including duration) is a red herring. Looking not too much further into the article on musical notes we find another meaning more relevant to this discussion: "A note can also represent a pitch class."

- A scale is a series of pitched sounds, not a pattern of fingerings, even though the mechanics of production may be grokked as being twined closely with the sound itself. I know a violist who keeps an instrument on stage, tuned down a half step to play in E major using more convenient F fingerings. It's still E major, as far as the rest of the band is concerned. IMHO, tempered or just tuning may be considered as variations in the rendering of the "same" scale, for the purposes of a first-order definition.

- Do you have suggestions for modifying the wording of the existing text? Just plain Bill (talk) 18:26, 20 November 2018 (UTC)

- This leads me to think that the pitch relationships are what is key in the scale. If a scale is defined in terms of a degrees of some musical temperament, then the temperament must be part of the definition of the scale - much more strongly than the root tone that I choose. −ClintGoss (talk) 17:12, 20 November 2018 (UTC)

- ClintGoss, interesting thought experiments. It seems to me that all of intonation, pitch relations and fingerings play a role. Playing a common major scale in C, feels certainly different from one in G on almost all instruments and needs separate practice exercises. The odd violist would be frowned upon in an orchestra because the audience would see him playing different notes from his co-players. By contrast I tend to agree that playing in A440 or A432 (both TET) would not merit to be termed a different scale. Now the question is how to catch this in a revised wording. −Woodstone (talk) 16:58, 21 November 2018 (UTC)

- To be clear, the violist I mentioned has no desire to play in an orchestral section. The dropped tuning works well for some pieces in a band with guitar, flute, and vocals. Most of the time, the instrument on their shoulder is one in standard CGDAE tuning. E major sits well on a guitar fingerboard, but is not a viola-friendly key for the kind of exposed accompaniment heard in that setting.

- What part of the existing wording is broken enough to need fixing? Just plain Bill (talk) 18:51, 21 November 2018 (UTC)

- ClintGoss, interesting thought experiments. It seems to me that all of intonation, pitch relations and fingerings play a role. Playing a common major scale in C, feels certainly different from one in G on almost all instruments and needs separate practice exercises. The odd violist would be frowned upon in an orchestra because the audience would see him playing different notes from his co-players. By contrast I tend to agree that playing in A440 or A432 (both TET) would not merit to be termed a different scale. Now the question is how to catch this in a revised wording. −Woodstone (talk) 16:58, 21 November 2018 (UTC)

Some changes

- The following discussion is closed. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made in a new section. A summary of the conclusions reached follows.

- Make bot archive this section. Michael Bednarek (talk) 03:07, 20 February 2019 (UTC)

folks:

(1) i moved the math-y discussion of scale degree out of the first paragraph and into the scale degree section;

(2) a scale is indeed an ordered series of notes, but that order is not just by pitch/frequency. in western music, think melodic minor scale: the scale is ordered by pitch and direction (asc/desc).

(3) i switched the frequency link to pitch, since frequency is very math-y, while pitch links to frequency in its first sentence.

(4) i removed the brief discussion of pentatonic and chromatic that preceded the scale list, as pentatonic scale includes scales that are not subsets of the chromatic scale: pelog, etc.

(5) i added pentatonic to the list of scale types, so it wouldn't get lost after the preceding edit. jp2 21:16 Apr 16, 2003 (UTC)

Hijaz scale

- The following discussion is closed. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made in a new section. A summary of the conclusions reached follows.

- Make bot archive this section. Michael Bednarek (talk) 03:07, 20 February 2019 (UTC)

Isn't the Hijaz scale the same as the Spanish and Jewish scale? (GCarty 18:04, 27 Sep 2004 (UTC))

Scales = or ≠

- The following discussion is closed. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made in a new section. A summary of the conclusions reached follows.

- Make bot archive this section. Michael Bednarek (talk) 03:07, 20 February 2019 (UTC)

Scales and intervals are not equivalent to their pitches or exact frequencies. There is no "the chromatic scale", but many chromatic scales. The most common one is the equal tempered chromatic scale, which would include only an approximate of a pelog scale or pelog scales. There are many tunings of pelog scales, with each ensemble having a different tuning, and there also exist justly tuned chromatic scales, and there are or could be chromatic scales which contain the exact intervals of a specific tuning of a pelog scale. A major third (just) is a ditone (pythagorean) is 4-semitones (equal temperament), but luckily each can serve as the other. My point in all this is that scales are the same or different depending on context, on what you need the scales to do. The Hijaz scale, if not simply another or the real name for the Spanish scale, may seemingly be identical but still be a seperate thing (that may nonetheless substitute for the other). Does I mean that we shouldn't make connections or redirects? I mean that we should be both more flexible and do more research. Hyacinth 20:37, 27 Sep 2004 (UTC)

New Term, it's my own, can I introduce it?

- The following discussion is closed. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made in a new section. A summary of the conclusions reached follows.

- Make bot archive this section. Michael Bednarek (talk) 03:07, 20 February 2019 (UTC)

I would like some feedback on how other contributors to the music theory sections of wikipedia would feel about my introducing a new piece of terminology which you may agree is potentially very useful. I realised several years ago that it would be possible to categorise different scales (I have described Just or 12 tone as "Tunings" not scales)with regard to how many notes they can share in common if their root notes are moved to the point where they have their maximum number of notes in common. For two modes of the same scale (e.g. Ionian ("Major") and Aeolian ("Minor") this value would be equal to the number of notes in each scale (7, not counting the octave of the root note) but for different "parent scales" (i.e. the orders of intervals from which modes can be chosen) these values are less. The size of this number (which I propose to call a "scale affinity" value) is a very simple numerical measure of similarity between scales. Generally speaking the changes of scale which are most appealing cut down on the number of different notes introduced each time, hence, in theory tables of scale affinities could provide paths between different scales which minimise dissonances. Also they would alert a musician to the fact that changing only one note from their current scale may lead them to another scale with which they may only have been within their grasp in another context. This could help a musician learn to learn how to improvise in novel ways. I have been using such tables for years and have a piece on my brother's website regarding the principle. Recently I've just learned how to use spreadsheets to enumerate similarities between scales in all possible alignments and intend to make the macros involved widely available, for free, through the internet. So my quandries are:

- I'm no expert on music theory and a term may already exist for this property, I would like to know if this is the case.

- If an amateur like myself introduces a new term and attaches a link to my scale theory website it may be regarded as a vain piece of self-aggrandisement. It is true that I wish to popularise this concept but is this the forum by which to do it?

My website is very, very ancient and needs updating, something I would have to consider doing before attaching such a scruffy thing to a major portal of communication like Wikipedia. I would welcome suggestions. Nonetheless you may wish to check it out by going to my brother's website http://www.classaxe.com/index.htm and then clicking on the links "Friends" (left hand side)and then "Andrew F." and then "scales resources". I expect that there are errors with some of the values but my MS Excel based method makes this process far more reliable.

I would be grateful for your comments.

you can email me if you wish:

u10ajf@yahoo.co.uk

Thanks.--U10ajf 00:25, 26 Jan 2005 (UTC)

- To give you quick answers: Sorry, no, it's not a new, it's not your own, and if it was you could not add it.

- See the recently created common tone and modulation (music) for the first, and Wikipedia:No original research for the latter. Hyacinth 01:13, 26 Jan 2005 (UTC)

Thank you for your comments. Nonetheless it seems to me that the common tone concept exclusively regards keys built from the same parent scale (the major scale and its modes) and isn't the same as the scale affnity concept which I introduced to compare different scale forms. (Major and Harmonic minor scales cohabit a group roughly similar to the closely related key group with only one note different). However I do acknowledge your point that wikipedia does not allow original research to be included and shall refrain from doing so. I should still be interested to hear from other wikipedia users if they have found the idea elsewhere since then I could reference their site instead of my own. I am new to Wikipedia, are there any more widely viewed noticeboards for peer review than the individual "discussion" postings which pertain - for my present purpose - too specifically to previous entries? Whether the concept is new or not I think that the enumeration of all the possible overlaps (12 each!) between the 47 different scale forms catalogued and where their constituent arpeggios lie may be of use to jazz musicians. Thanks for your time. Andrew --U10ajf 03:16, 26 Jan 2005 (UTC)

- You're welcome, your discovery is insightful and I think your lists would be useful. Hyacinth 05:11, 26 Jan 2005 (UTC)

- See also: L'Isle Joyeuse. Hyacinth 16:27, 26 Jan 2005 (UTC)

72 in Carnatic

"Other traditional tempered scale systems divide the octave to equal intervals by numbers other than 12. Examples are 53 in the Middle East, and 72 in southern India Carnatic Music."

The part about 72 in Carnatic music is incorrect, I believe. There are a few areas I believe the misunderstanding may lie.

The 22 shruti system. There is microtonality in Indian music. But the 22 shruti are not equidistant from one another, and the smallest interval is 22 cents (72edo would be about 17 cents I believe).

There are 72 melakarta ragas in Carnatic music. (There are many, many more ragas than just that, but the 72 melakarta ragas are the ones from which the rest are derived.)

131.230.75.57 (talk) 00:53, 13 November 2019 (UTC)

- Absolutely correct. That ridiculous claim was not verified by a reliable source, and had been challenged since September 2018. I have therefore deleted it. Thank you for drawing attention to this matter.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 03:33, 13 November 2019 (UTC)

Table of intervals by scale

I would like to see a breakdown of the most common western clasical scales by the number of semitones in each interval. For example the major scales all have the same interval, just start on a different note. The information is contained in various pages, but not collated for convenience. Something like this Tradimus (talk) 13:39, 26 January 2021 (UTC)

| Type of Scale | First interval | Second interval | Third Interval | Fourth Interval | Fifth Interval | Sixth Interval | Seventh Interval | Eighth Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Scale | 2 semitones | 2 | 1 semitone | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Natural Minor Scale | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ? | |

| Harmonic Minor Scale | ||||||||

| Melodic Minor Scale | ||||||||

| Pentatonic Scale | ||||||||

| Hungarian Minor Scale | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Blues | ||||||||

| et cetera |