Temple in Jerusalem

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

The Temple in Jerusalem, or alternatively the Holy Temple (Hebrew: בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ, Modern: Bēt haMīqdaš, Tiberian: Bēṯ hamMīqdāš; Arabic: بيت المقدس, Bayt al-Maqdis), refers to the two religious structures that served as the central places of worship for Israelites and Jews on the modern-day Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem. According to the Hebrew Bible, the First Temple was built in the 10th century BCE, during the reign of Solomon over the United Kingdom of Israel. It stood until c. 587 BCE, when it was destroyed during the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem.[1] Almost a century later, the First Temple was replaced by the Second Temple, which was built after the Neo-Babylonian Empire was conquered by the Achaemenid Persian Empire. While the Second Temple stood for a longer period of time than the First Temple, it was likewise destroyed during the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

Projects to build the hypothetical "Third Temple" have not come to fruition in the modern era, though the Temple in Jerusalem still features prominently in Judaism.[2] As an object of longing and a symbol of future redemption, the Temple has been commemorated in Jewish tradition through prayer, liturgical poetry, art, poetry, architecture, and other forms of expression.

Outside of Judaism, the Temple (and today's Temple Mount) also carries a high level of significance in Islam and Christianity. One of the early Arabic names for Jerusalem is Bayt al-Maqdis, which preserves the memory of the Temple. The Temple Mount is home to two monumental Islamic structures, the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque, which date to the Umayyad period. The site, known to Muslims as the "Al-Aqsa Mosque compound" or Haram al-Sharif, is considered the third-holiest site in Islam. The Christian New Testament and tradition hold that important events in Jesus' life took place in the Temple, and the Crusaders attributed the name "Templum Domini" ("Temple of the Lord") to the Dome of the Rock.

Etymology

The Hebrew name given in the Hebrew Bible for the building complex is either Mikdash (Hebrew: מקדש), as used in Exodus,[3] or simply Bayt / Beit Adonai (Hebrew: בית), as used in 1 Chronicles.[4]

In rabbinic literature, the temple sanctuary is called Beit HaMikdash (Hebrew: בית המקדש), meaning, "The Holy House", and only the Temple in Jerusalem is referred to by this name.[5][better source needed] In classic English texts, however, the word "Temple" is used interchangeably, sometimes having the strict connotation of the Temple precincts, with its courts (Greek: ἱερὸν), while at other times having the strict connotation of the Temple Sanctuary (Greek: ναός).[6] While Greek and Hebrew texts make this distinction, English texts do not always do so.

Jewish rabbi and philosopher Maimonides gave the following definition of "Temple" in his Mishne Torah (Hil. Beit Ha-Bechirah):

They are enjoined to make, in what concerns it (i.e. the building of the Temple), a holy site and an inner-sanctum,[a] and where there is positioned in front of the holy site a certain place that is called a 'Hall' (Hebrew: אולם). The three of these places are called 'Sanctuary' (Hebrew: היכל). They are [also] enjoined to make a different partition surrounding the Sanctuary, distant from it, similar to the screen-like hangings of the court that were in the wilderness.[7] All that which is surrounded by this partition, which, as noted, is like the court of the Tabernacle, is called 'Courtyard' (Hebrew: עזרה), whereas all of it together is called 'Temple' (Hebrew: מקדש) [lit. 'the Holy Place'].[8][b]

First Temple

The Hebrew Bible says that the First Temple was built by King Solomon,[9] completed in 957 BCE.[10] According to the Book of Deuteronomy, as the sole place of Israelite korban (sacrifice),[11] the Temple replaced the Tabernacle constructed in the Sinai under the auspices of Moses, as well as local sanctuaries, and altars in the hills.[12] This Temple was sacked a few decades later by Shoshenq I, Pharaoh of Egypt.[13]

Although efforts were made at partial reconstruction, it was only in 835 BCE when Jehoash, King of Judah, in the second year of his reign invested considerable sums in reconstruction, only to have it stripped again for Sennacherib, King of Assyria c. 700 BCE.[citation needed] The First Temple was totally destroyed in the Siege of Jerusalem by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE.[c]

Second Temple

According to the Book of Ezra, construction of the Second Temple was called for by Cyrus the Great and began in 538 BCE,[14] after the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire the year before.[15] According to some 19th-century calculations, work started later, in April 536 BCE[16] and was completed on 21 February, 515 BCE, 21 years after the start of the construction. This date is obtained by coordinating Ezra 3:8–10[17] (the third day of Adar, in the sixth year of the reign of Darius the Great) with historical sources.[18] The accuracy of these dates is contested by some modern researchers, who consider the biblical text to be of later date and based on a combination of historical records and religious considerations, leading to contradictions between different books of the Bible and making the dates unreliable.[19] The new temple was dedicated by the Jewish governor Zerubbabel. However, with a full reading of the Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah, there were four edicts to build the Second Temple, which were issued by three kings: Cyrus in 536 BCE (Ezra ch. 1), Darius I of Persia in 519 BCE (ch. 6), and Artaxerxes I of Persia in 457 BCE (ch. 7), and finally by Artaxerxes again in 444 BCE (Nehemiah ch. 2).[20]

According to classical Jewish sources, another demolition of the Temple was narrowly avoided in 332 BCE when the Jews refused to acknowledge the deification of Alexander the Great of Macedonia, but Alexander was placated at the last minute by astute diplomacy and flattery.[21]

After Jerusalem came under Seleucid rule, Antiochus III attempted to introduce the Greek pantheon into the temple. A rebellion ensued and was brutally crushed, but no further action by Antiochus was taken. When Antiochus IV Epiphanes assumed the Seleucid thrown he immediately attempted to enforce universal Hellenization once again. During this time, several incidents considered offensive under traditional Jewish practice occurred in the temple, to include erecting a statute of Zeus and the sacrifice of pigs. This led to a two year civil war in Judea in which traditionalist rebels led by Mattathias fought against both Seleucid forces and the Hellenized Judean forces who administered Judea in Antiochus's name. After the rebels successfully overthrew Seleucid rule, Mattathias' son Judah Maccabee re-dedicated the temple in 164 BCE, giving rise to the celebration of Hanukkah.[9]

During the Roman era, Pompey entered (and thereby desecrated) the Holy of Holies in 63 BCE, but left the Temple intact.[22][23][24] In 54 BCE, Crassus looted the Temple treasury.[25][26]

Around 20 BCE, the building was renovated and expanded by Herod the Great, and became known as Herod's Temple. It was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE during the Siege of Jerusalem. During the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Romans in 132–135 CE, Simon bar Kokhba and Rabbi Akiva wanted to rebuild the Temple, but bar Kokhba's revolt failed and the Jews were banned from Jerusalem (except for Tisha B'Av) by the Roman Empire. The emperor Julian allowed the Temple to be rebuilt, but the Galilee earthquake of 363 ended all attempts ever since.[citation needed]

Al-Aqsa and the Third Temple

By the 7th century, the site had fallen into disrepair under Byzantine rule. After the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem in the 7th century during the Rashidun Caliphate, a mosque was built by caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab (reigned 634–644 CE) who first cleared the site of debris and then erected a mihrab and simple mosque on the same site as the present mosque. This first mosque construction was known as Masjid al-'Umari. During the Umayyad caliphate, the caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ordered a renovation of the Islamic mosque, constructing the Dome of the Rock, on the Temple Mount. The mosque has stood on the mount since 691 CE; the Jami Al-Aqsa. It has been renovated several times since, including during the Abbasid, Fatimid, Mamluk, and Ottoman eras.[27]

Archaeological evidence

Archaeological excavations have found remnants of both the First Temple and the Second Temple. Among the artifacts of the First Temple are dozens of ritual immersion pools in this area surrounding the Temple Mount,[28] as well as a large square platform identified by architectural archaeologist Leen Ritmeyer as likely being built by King Hezekiah c. 700 BCE as a gathering area in front of the Temple.

Concrete finds from the Second Temple include the Temple Warning inscriptions and the Trumpeting Place inscription, two surviving pieces of the Herodian expansion of the Temple Mount. The Temple Warning inscriptions forbid the entry of pagans to the Temple, a prohibition also mentioned by the 1st century CE historian Josephus. These inscriptions were on the wall that surrounded the Temple and prevented non-Jews from entering the temple's courtyard. The Trumpeting Place inscription was found at the southwest corner of Temple Mount, and is believed to mark the site where the priests used to declare the advent of Shabbat and other Jewish holidays.[29]

Ritual objects used in the temple service were carried off and many are likely located in museum collections, in particular, that of the Vatican Museums.[30]

Location

There are three main theories as to where the Temple stood: where the Dome of the Rock is now located, to the north of the Dome of the Rock (Professor Asher Kaufman), or to the east of the Dome of the Rock (Professor Joseph Patrich of the Hebrew University).[31]

The exact location of the Temple is a contentious issue, as questioning the exact placement of the Temple is often associated with Temple denial. Since the Holy of Holies lay at the center of the complex as a whole, the Temple's location is dependent on the location of the Holy of Holies. The location of the Holy of Holies was even a question less than 150 years after the Second Temple's destruction, as detailed in the Talmud. Chapter 54 of the Tractate Berakhot states that the Holy of Holies was directly aligned with the Golden Gate, which, assuming the current gate follows the same course as the now buried Herodian gate, would have placed the Temple slightly to the north of the Dome of the Rock, as Kaufman postulated.[32] However, chapter 54 of the Tractate Yoma and chapter 26 of the Tractate Sanhedrin assert that the Holy of Holies stood directly on the Foundation Stone, which agrees with the traditional view that the Dome of the Rock stands on the Temple's location.[33][34]

Physical layout

This section uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (January 2024) |

First Temple

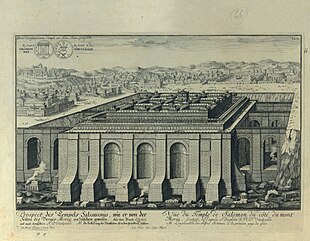

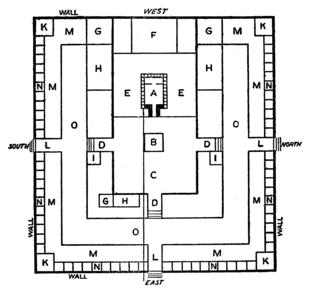

The Temple of Solomon, or First Temple, consisted of four main elements:

- the Great or Outer Court, where people assembled to worship;[35]

- the Inner Court[36] or Court of the Priests;[37]

- and the Temple building itself, with

- the larger Holy Place (hekhal), called the "greater house"[38] and the "temple"[39] and

- the smaller "inner sanctum", known as the Holy of Holies[40] or Kodesh HaKodashim.

Second Temple

In the case of the last and most elaborate structure, the Herodian Temple, the structure consisted of the wider Temple precinct, the restricted Temple courts, and the Temple building itself:

- Temple precinct, located on the extended Temple Mount platform, and including the Court of the Gentiles

- Court of the Women or Ezrat HaNashim

- Court of the Israelites, reserved for ritually pure Jewish men

- Court of the Priests, whose relation to the Temple Court is interpreted in different ways by scholars

- Temple Court or Azarah, with the Brazen Laver (kiyor), the Altar of Burnt Offerings (mizbe'ah), the Place of Slaughtering, and the Temple building itself

The Temple edifice had three distinct chambers:

- Temple vestibule or porch (ulam)

- Temple sanctuary (hekhal or heikal), the main part of the building

- Holy of Holies (Kodesh HaKodashim or debir), the innermost chamber

According to the Talmud, the Women's Court was to the east and the main area of the Temple to the west.[41] The main area contained the butchering area for the sacrifices and the Outer Altar on which portions of most offerings were burned. An edifice contained the ulam (antechamber), the hekhal (the "sanctuary"), and the Holy of Holies. The sanctuary and the Holy of Holies were separated by a wall in the First Temple and by two curtains in the Second Temple. The sanctuary contained the seven branched candlestick, the table of showbread and the Incense Altar.

The main courtyard had thirteen gates. On the south side, beginning with the southwest corner, there were four gates:

- The Upper Gate (Sha'ar HaElyon)

- The Kindling Gate (Sha'ar HaDelek), where wood was brought in

- The Gate of Firstborns (Sha'ar HaBechorot), where people with first-born animal offerings entered

- The Water Gate (Sha'ar HaMayim), where the Water Libation entered on Sukkot/the Feast of Tabernacles

On the north side, beginning with the northwest corner, there were four gates:

- The Gate of Jeconiah (Sha'ar Yechonyah), where kings of the Davidic line enter and Jeconiah left for the last time to captivity after being dethroned by the King of Babylon

- The Gate of the Offering (Sha'ar HaKorban), where priests entered with kodshei kodashim offerings

- The Women's Gate (Sha'ar HaNashim), where women entered into the Azara or main courtyard to perform offerings[42]

- The Gate of Song (Sha'ar HaShir), where the Levites entered with their musical instruments.

The Hall of Hewn Stones (Hebrew: לשכת הגזית Lishkat haGazit), also known as the Chamber of Hewn Stone, was the meeting place, or council-chamber, of the Sanhedrin during the Second Temple period (6th century BCE – 1st century CE). The Talmud deduces that it was built into the north wall of the Temple in Jerusalem, half inside the sanctuary and half outside, with doors providing access both to the temple and to the outside. The chamber is said to have resembled a basilica in appearance,[43] having two entrances: one in the east and one in the west.[44]

On the east side was the Gate of Nicanor, between the Women's Courtyard and the main Temple Courtyard, which had two minor doorways, one on its right and one on its left. On the western wall, which was relatively unimportant, there were two gates that did not have any name.

The Mishnah lists concentric circles of holiness surrounding the Temple: Holy of Holies; Sanctuary; Vestibule; Court of the Priests; Court of the Israelites; Court of the Women; Temple Mount; the walled city of Jerusalem; all the walled cities of the Land of Israel; and the borders of the Land of Israel.

The Talmud speaks also of important presents which Queen Helena of Adiabene gave to the Temple at Jerusalem.[45] "Helena had a golden candlestick made over the door of the Temple," to which statement is added that when the sun rose its rays were reflected from the candlestick and everybody knew that it was the time for reading the Shema'.[46] She also made a golden plate on which was written the passage of the Pentateuch[47] which the Kohen read when a wife suspected of infidelity was brought before him.[48] In the Jerusalem Talmud, tractate Yoma iii. 8 the candlestick and the plate are confused.

Temple services

This section uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (January 2024) |

The Temple was the place where offerings described in the course of the Hebrew Bible were carried out, including daily morning and afternoon offerings and special offerings on Sabbath and Jewish holidays. Levites recited Psalms at appropriate moments during the offerings, including the Psalm of the Day, special psalms for the new month, and other occasions, the Hallel during major Jewish holidays, and psalms for special sacrifices such as the "Psalm for the Thanksgiving Offering" (Psalm 100).

As part of the daily offering, a prayer service was performed in the Temple which was used as the basis of the traditional Jewish (morning) service recited to this day, including well-known prayers such as the Shema, and the Priestly Blessing. The Mishna describes it as follows:

The superintendent said to them, bless one benediction! and they blessed, and read the Ten Commandments, and the Shema, "And it shall come to pass if you will hearken", and "And [God] spoke...". They pronounced three benedictions with the people present: "True and firm", and the "Avodah" "Accept, Lord our God, the service of your people Israel, and the fire-offerings of Israel and their prayer receive with favor. Blessed is He who receives the service of His people Israel with favor" (similar to what is today the 17th blessing of the Amidah), and the Priestly Blessing, and on the Sabbath they recited one blessing; "May He who causes His name to dwell in this House, cause to dwell among you love and brotherliness, peace and friendship" on behalf of the weekly Priestly Guard that departed.

In addition to the sacrifices, the Temple was considered a special location for prayer to God:

When Your people Israel are smitten down before the enemy, when they sin against You, if they turn again to You, and confess Your name, and pray and make supplication to You in this house - may You hear in heaven, and forgive the sin of Your people Israel, and bring them back to the land which You gave to their fathers. ... If there be in the land famine, if there be pestilence, if there be blasting or mildew, locust or caterpillar; if their enemy besiege them in the land of their cities; whatever plague, whatever sickness there be; whatever prayer and supplication be made by any person of all Your people Israel, who shall know every man the plague of his own heart, and spread forth his hands toward this house - may You hear in heaven Your dwelling-place, and forgive, and do, and render to every man according to all his ways, whose heart You know.[49]

In the Talmud

Seder Kodashim, the fifth order, or division, of the Mishnah (compiled between 200 and 220 CE), provides detailed descriptions and discussions of the religious laws connected with Temple service including the sacrifices, the Temple and its furnishings, as well as the priests who carried out the duties and ceremonies of its service. Tractates of the order deal with the sacrifices of animals, birds, and meal offerings, the laws of bringing a sacrifice, such as the sin offering and the guilt offering, and the laws of misappropriation of sacred property. In addition, the order contains a description of the Second Temple (tractate Middot), and a description and rules about the daily sacrifice service in the Temple (tractate Tamid).[50][51][52]

In the Babylonian Talmud, all the tractates have Gemara – rabbinical commentary and analysis – for all their chapters; some chapters of Tamid, and none on Middot and Kinnim. The Jerusalem Talmud has no Gemara on any of the tractates of Kodashim.[51][52]

The Talmud (Yoma 9b) describes traditional theological reasons for the destruction: "Why was the first Temple destroyed? Because the three cardinal sins were rampant in society: idol worship, licentiousness, and murder… And why then was the second Temple – wherein the society was involved in Torah, commandments and acts of kindness – destroyed? Because gratuitous hatred was rampant in society."[53][54][better source needed]

Role in contemporary Jewish services

Part of the traditional Jewish morning service, the part surrounding the Shema prayer, is essentially unchanged from the daily worship service performed in the Temple. In addition, the Amidah prayer traditionally replaces the Temple's daily tamid and special-occasion Mussaf (additional) offerings (there are separate versions for the different types of sacrifices). They are recited during the times their corresponding offerings were performed in the Temple.

The Temple is mentioned extensively in Orthodox services. Conservative Judaism retains mentions of the Temple and its restoration, but removes references to the sacrifices. References to sacrifices on holidays are made in the past tense, and petitions for their restoration are removed. Mentions in Orthodox Jewish services include:

- A daily recital of Biblical and Talmudic passages related to the korbanot (sacrifices) performed in the Temple (See korbanot in siddur).

- References to the restoration of the Temple and sacrificial worships in the daily Amidah prayer, the central prayer in Judaism.

- A traditional personal plea for the restoration of the Temple at the end of private recitation of the Amidah.

- A prayer for the restoration of the "house of our lives" and the shekhinah (divine presence) "to dwell among us" is recited during the Amidah prayer.

- Recitation of the Psalm of the day; the psalm sung by the Levites in the Temple for that day during the daily morning service.

- Numerous psalms sung as part of the ordinary service make extensive references to the Temple and Temple worship.

- Recitation of the special Jewish holiday prayers for the restoration of the Temple and their offering, during the Mussaf services on Jewish holidays.

- An extensive recitation of the special Temple service for Yom Kippur during the service for that holiday.

- Special services for Sukkot (Hakafot) contain extensive (but generally obscure) references to the special Temple service performed on that day.

The destruction of the Temple is mourned on the Jewish fast day of Tisha B'Av. Three other minor fasts (Tenth of Tevet, 17th of Tammuz, and Third of Tishrei), also mourn events leading to or following the destruction of the Temple. There are also mourning practices which are observed at all times, for example, the requirement to leave part of the house unplastered.

Recent history

The Temple Mount, along with the entire Old City of Jerusalem, was captured from Jordan by Israel in 1967 during the Six-Day War, allowing Jews once again to visit the holy site.[55][better source needed][56] Jordan had occupied East Jerusalem and the Temple Mount immediately following Israel's declaration of independence on May 14, 1948. Israel officially unified East Jerusalem, including the Temple Mount, with the rest of Jerusalem in 1980 under the Jerusalem Law, though United Nations Security Council Resolution 478 declared the Jerusalem Law to be in violation of international law.[citation needed] The Jerusalem Islamic Waqf, based in Jordan, has administrative control of the Temple Mount.[citation needed]

In other religions

Christianity

According to Matthew 24:2,[57] Jesus predicts the destruction of the Second Temple. This idea, of the Temple as the body of Christ, became a rich and multi-layered theme in medieval Christian thought (where Temple/body can be the heavenly body of Christ, the ecclesial body of the Church, and the Eucharistic body on the altar).[58]

Islam

The Temple Mount bears significance in Islam as it acted as a sanctuary for the Hebrew prophets and the Israelites. Islamic tradition says that a temple was first built on the Temple Mount by Solomon, the son of David. After the destruction of the second temple, it was rebuilt by the second Rashidun Caliph, Omar, which stands until today as Al-Aqsa Mosque. Traditionally referred to as the "Farthest Mosque" (al-masjid al-aqṣa' literally "utmost site of bowing (in worship)" though the term now refers specifically to the mosque in the southern wall of the compound which today is known simply as al-haram ash-sharīf "the noble sanctuary"), the site is seen as the destination of Muhammad's Night Journey, one of the most significant events recounted in the Quran and the place of his ascent heavenwards thereafter (Mi'raj). Muslims view the Temple in Jerusalem as their inheritance, being the followers of the last prophet of God and believers in every prophet sent, including the prophets Moses and Solomon. To Muslims, Al-Aqsa Mosque is not built on top of the temple, rather, it is the Third Temple, and they are the true believers who worship in it, whereas Jews and Christians are disbelievers who do not believe in God's final prophets Jesus and Muhammad.[59][60]

In Islam, Muslims are encouraged to visit Jerusalem and pray at Al-Aqsa Mosque. There are over forty hadith about Al-Aqsa Mosque and the virtue of visiting and praying in it, or at least sending oil to light its lamps. In a hadith compiled by Al-Tabarani, Bayhaqi, and Suyuti, the Prophet Muhammad said, "A prayer in Makkah (Ka’bah) is worth 1,000,000 times (reward), a prayer in my mosque (Madinah) is worth 1,000 times and a prayer in Al-Aqsa Sanctuary is worth 500 times more reward than anywhere else." Another hadith compiled by imams Muhammad al-Bukhari, Muslim, and Abu Dawud expounds on the importance of visiting the holy site. In another hadith the prophet Muhammad said, "You should not undertake a special journey to visit any place other than the following three Masjids with the expectations of getting greater reward: the Sacred Masjid of Makkah (Ka’bah), this Masjid of mine (the Prophet’s Masjid in Madinah), and Masjid Al-Aqsa (of Jerusalem)."[61]

According to Seyyed Hossein Nasr, professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University, Jerusalem (i.e., the Temple Mount) has the significance as a holy site/sanctuary ("haram") for Muslims primarily in three ways, the first two being connected to the Temple.[62] First, Muhammad (and his companions) prayed facing the Temple in Jerusalem (referred to as "Bayt Al-Maqdis", in the Hadiths) similar to the Jews before changing it to the Kaaba in Mecca sixteen months after arriving in Medina following the verses revealed (Sura 2:144, 149–150). Secondly, during the Meccan part of his life, he reported to have been to Jerusalem by night and prayed in the Temple, as the first part of his otherworldly journey (Isra and Mi'raj).

Imam Abdul Hadi Palazzi, leader of Italian Muslim Assembly, quotes the Quran to support Judaism's special connection to the Temple Mount. According to Palazzi, "The most authoritative Islamic sources affirm the Temples". He adds that Jerusalem is sacred to Muslims because of its prior holiness to Jews and its standing as home to the biblical prophets and kings David and Solomon, all of whom he says are sacred figures in Islam. He claims that the Quran "expressly recognizes that Jerusalem plays the same role for Jews that Mecca has for Muslims".[63]

Building a Third Temple

Ever since the Second Temple's destruction, a prayer for the construction of a Third Temple has been a formal and mandatory part of the thrice-daily Jewish prayer services. However, the question of whether and when to construct the Third Temple is disputed both within the Jewish community and without; groups within Judaism argue both for and against construction of a new Temple, while the expansion of Abrahamic religion since the 1st century CE has made the issue contentious within Christian and Islamic thought as well. Furthermore, the complicated political status of Jerusalem makes reconstruction difficult, while Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock have been constructed at the traditional physical location of the Temple.

In 363 CE, the Roman emperor Julian had ordered Alypius of Antioch to rebuild the Temple as part of his campaign to strengthen non-Christian religions.[64] The attempt failed, with contemporary accounts mentioning divine fire falling from Heaven but also perhaps due to sabotage, an accidental fire, or an earthquake in Galilee.

The Book of Ezekiel prophesies what would be the Third Temple, noting it as an eternal house of prayer and describing it in detail.

In media

A journalistic depiction of the controversies around the Jerusalem Temple was presented in the 2010 documentary Lost Temple by Serge Grankin. The film contains interviews with religious and academic authorities involved in the issue. German journalist Dirk-Martin Heinzelmann, featured in the film, presents the point of view of Prof. Joseph Patrich (the Hebrew University), stemming from the underground cistern mapping made by Charles William Wilson (1836–1905).[65]

See also

- Jewish Temple at Elephantine (7th? 6th? – mid-4th century BCE)

- Jewish Temple of Leontopolis (c. 170 BCE – 73 CE)

- Temple of Solomon (São Paulo), a replica built by a Brazil-based church

- Synagogue

- Similar Iron Age temples from the region

- 'Ain Dara temple[66]

- Ebla (Temple D)[66]

- Emar temple[66]

- Mumbaqat temple[66]

- Tell Tayinat temple (8th century BCE)[66]

Notes

- ^ Lit. "holy of holies"

- ^ The historian Josephus echoes this same theme, when he writes The Jewish War 5.5.2. (5.193–194): "When one proceeds through the cloisters to the second court of the temple, there was a stone partition all round, whose height was three cubits and of most elegant construction. Upon it stood pillars, at equal distances from one another, declaring the law of purity, some in Greek and some in Roman letters, that 'no foreigner should go within the Holy Place,' for that second [court of the] temple was called 'the Holy Place,' and was ascended to by fourteen steps from the first court."

- ^ New American Oxford Dictionary: "Temple".

References

- ^ Miller, J. Maxwell; Hayes, John H. (2006). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah (2nd ed.). Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 478ff. ISBN 978-0664223588.

- ^ "The History of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem". Haaretz. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Exodus 25:8

- ^ 1 Chronicles 22:11

- ^ "The Jewish Temple (Beit HaMikdash)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Williamson, G. A., ed. (1980). Josephus – The Jewish War. Middlesex, U.K.: The Penguin Classics. p. 290 (note 2). OCLC 633813720.

Throughout this translation 'Sanctuary' represents Greek naos and denotes the central shrine, while 'Temple' represents hieron and includes the courts, colonnades, etc. surrounding the shrine.

(OCLC 1170073907) (reprint) - ^ Exodus 39:40

- ^ Maimonides (1974). Sefer Mishneh Torah – HaYad Ha-Chazakah (Maimonides' Code of Jewish Law) (in Hebrew). Vol. 4. Jerusalem: Pe'er HaTorah., s.v. Hil. Beit Ha-Bechirah 1:5

- ^ a b "Temple, the." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Temple of Jerusalem | Description, History, & Significance". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Deuteronomy 12:2–27

- ^ Durant, Will. Our Oriental Heritage. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1954. p. 307. See 1 Kings 3:2.

- ^ Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, p. 335, Oxford 2000

- ^ Shalem, Yisrael (1997). "Second Temple Period (538 BCE to 70 CE): Persian Rule". Jerusalem: Life Throughout the Ages in a Holy City. Ramat-Gan, Israel: Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies, Bar-Ilan University. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-107-00960-8. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Haggai 1:15

- ^ Ezra 3:8–10

- ^ Jamieson, Robert; Fausset, A. R.; Brown, David (1882). "Ezra 6:13–15. The Temple Finished". A Commentary, Critical, Practical, and Explanatory on the Old and New Testaments. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020 – via BibleHub.com.

- ^ Edelman, Diana (2014). "The Seventy-Year Tradition Revisited". The Origins of the 'Second' Temple: Persion Imperial Policy and the Rebuilding of Jerusalem (reprint, revised ed.). Routledge. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-1-84553-016-7. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ 'Abdu'l-Baha (ed.). Some Answered Questions. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ "Shimon HaTzaddik". Orthodox Union. 14 June 2006. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Josephus, The New Complete Works, translated by William Whiston, Kregel Publications, 1999, "Antiquites" Book 14:4, pp. 459–460

- ^ Michael Grant, The Jews in the Roman World, Barnes & Noble, 1973, p. 54

- ^ Peter Richardson, Herod: King of the Jews and Friend of the Romans, Univ. of South Carolina Press, 1996, pp. 98–99

- ^ Josephus, The New Complete Works, translated by William Whiston, Kregel Publications, 1999, "Antiquites" Book 14:7, p. 463

- ^ Michael Grant, The Jews in the Roman World, Barnes & Noble, 1973, p. 58

- ^ "Aqsa Mosque – Discover Islamic Art – Virtual Museum". islamicart.museumwnf.org. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ "Were there Jewish Temples on Temple Mount? Yes – Israel News". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Were There Jewish Temples on Temple Mount? Yes". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Moskoff, Harry H. (10 February 2022). "Is there new evidence of Jewish Temple treasures in the Vatican?". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ See article in the World Jewish Digest, April 2007

- ^ "Berakhot 54a:7". Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Yoma 54b:2". Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Sanhedrin 26b:5". Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Jeremiah 19:14; 26:2

- ^ 1 Kings 6:36

- ^ 2 Chr. 4:9

- ^ 2 Chr. 3:5

- ^ 1 Kings 6:17

- ^ Michael M. Homan (2007). "The Tabernacle and the Temple in Ancient Israel". Religion Compass. 1 (1). Wiley-Blackwell: Blackwell Publishing: 43. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2006.00006.x. ISSN 1749-8171. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

and the cube-shaped back room, the Holy of Holies (Hebrew debîr)

- ^ Mishna Tractate Midos.

- ^ "Sheyibaneh Beit Hamikdash: Women in the Azara?". Archived from the original on 29 July 2006.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud (Yoma 25a)

- ^ Mishnah Taharoth 6:8, Commentary of Rabbi Hai Gaon, s.v. בסילקי

- ^ Yoma 37a.

- ^ Yoma 37b; Tosefta Yoma 82

- ^ Numbers 19–22

- ^ Yoma l.c.

- ^ 1 Kings 8:33–39

- ^ Birnbaum, Philip (1975). "Kodashim". A Book of Jewish Concepts. New York, New York: Hebrew Publishing Company. pp. 541–542. ISBN 088482876X.

- ^ a b Epstein, Isidore, ed. (1948). "Introduction to Seder Kodashim". The Babylonian Talmud. Vol. 5. Singer, M. H. (translator). London: The Soncino Press. pp. xvii–xxi.

- ^ a b Arzi, Abraham (1978). "Kodashim". Encyclopedia Judaica. Vol. 10 (1st ed.). Jerusalem, Israel: Keter Publishing House Ltd. pp. 1126–1127.

- ^ "Gratuitous Hatred – What is it and Why is it so bad?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ "Hatred". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ "The Liberation of the Temple Mount and Western Wall (June 1967)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "1967: Reunification of Jerusalem". www.sixdaywar.org. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Matthew 24:2

- ^ See Jennifer A. Harris, "The Body as Temple in the High Middle Ages", in Albert I. Baumgarten ed., Sacrifice in Religious Experience, Leiden, 2002, pp. 233–256.

- ^ Anderson, James (2018). "The Centrality of Covenant Theology to the Islamic Faith" (PDF). Reformed Theological Seminary. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Carr, Gregory (18 March 2020). "A Brief History of the Temple of Jerusalem". Halaqa. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "Masjid Al Aqsa: The Best Place of Residence – 40 Ahadith". Sabeel Travels. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "The Spiritual Significance of Jerusalem: The Islamic Vision. The Islamic Quarterly. 4 (1998): pp. 233–242

- ^ Margolis, David (23 February 2001). "The Muslim Zionist". Los Angeles Jewish Journal.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 23.1.2–3.

- ^ "Lost Temple". 1 January 2000. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2018 – via IMDb.

- ^ a b c d e Monson, John M. (June 1999). "The Temple of Solomon: Heart of Jerusalem". In Hess, Richard S.; Wenham, Gordon J. (eds.). Zion, city of our God | C. The Ain Dara Temple:A New Parallel from Syria. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 12–19. ISBN 978-0-8028-4426-2. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

Further reading

- Biblical Archaeology Review, issues: July/August 1983, November/December 1989, March/April 1992, July/August 1999, September/October 1999, March/April 2000, September/October 2005

- Ritmeyer, Leen. The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Jerusalem:, Israel Carta, 2006. ISBN 965-220-628-8

- Hamblin, William and David Seely, Solomon's Temple: Myth and History (Thames and Hudson, 2007) ISBN 0-500-25133-9

- Yaron Eliav, God's Mountain: The Temple Mount in Time, Place and Memory (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005)

- Rachel Elior, The Jerusalem Temple: The Representation of the Imperceptible, Studies in Spirituality 11 (2001), pp. 126–143

External links

- Visit of the Temple Institute Museum in Jerusalem conducted by Rav Israel Ariel Archived 26 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Video tour of a model of the future temple described in Ezekiel chapters 40–49 from a Christian perspective Archived 2008-05-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Rachel Elior, "The Jerusalem Temple – The Representation of the Imperceptible", Studies in Spirituality 11 (2001): 126–143

- The Centrality of Covenant Theology to the Islamic Faith

- A Brief History of the Temple of Jerusalem