The Garden of Death (Madetoja)

| The Garden of Death | |

|---|---|

| Piano suite by Leevi Madetoja | |

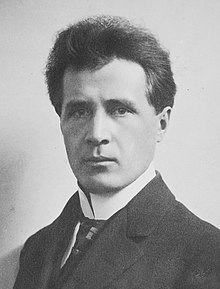

The composer (c. 1915–1918) | |

| Native name | Kuoleman puutarha |

| Opus | 41 |

| Composed | 1918, rev. 1919 |

| Publisher | Edition Wilhelm Hansen (1921) |

| Duration | Approx. 14 minutes |

| Movements | 3 |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 19 March 1923 |

| Location | Helsinki, Finland |

| Performers | Elli Rängman-Björlin |

The Garden of Death (in Finnish: Kuoleman puutarha; also known by its French title: Jardin de la mort),[a] Op. 41, is a three-movement suite for solo piano written in 1918 (Movement I) and revised in 1919 (the addition of Movements II–III) by Finnish composer Leevi Madetoja. The suite, somber and mournful in character, is a tribute to the composer's brother, Yrjö, who as a captive during the Finnish Civil War was executed by the Red Guards. The Finnish pianist Elli Rängman-Björlin premiered the suite in Helsinki, Finland, on 19 March 1923, with Madetoja in attendance.

History

[edit]Composition

[edit]In late January 1918, the embers of the First World War ignited into civil war between socialist Reds and the nationalist Whites. A few months later, the war brought personal tragedy to Madetoja: on 9 April, Red Guards captured and executed Yrjö Madetoja, Leevi's brother, during the Battle of Antrea in Kavantsaari.[b] It fell to Leevi to inform his mother:

I received a telegram from Viipuri yesterday that made my blood run cold: "Yjrö fell on the 13th day of April" was the message in all its terrible brevity. This unforeseen, shocking news fills us with unutterable grief. Death, that cruel companion of war and persecution, has not therefore spared us either; it has come to visit us, to snatch one of us as its victim. Oh when will we see the day when the forces of hatred vanish from the world and the good spirits of peace can return to heal the wounds inflicted by suffering and misery?

— Leevi Madetoja, in a 5 May 1918 letter to his mother, Anna[4]

Around this time, Madetoja also published in Lumikukkia magazine a short piece for solo piano, originally titled Improvisation in Memory of my Brother Yrjö (lmprovisationi Yrjö-veljeni muislolle). In 1919, Madetoja expanded the piece into a three-movement suite, renaming it The Garden of Death and removing the reference to his brother.[4] Notably, the suite shares melodic motifs with the Symphony No. 2 (Op. 35, 1918), which too finds its "deeply scarred" composer reflecting upon national tragedy and personal loss.

The Danish publishing house Edition Wilhelm Hansen published The Garden of Death in 1921. A year later in autumn, the German music magazine Signale (No. 35) published a glowing review of the score.[4] "No truly musical person will regret making the acquaintance of this fine piano poem", the anonymous critic wrote. "These short piano pieces provide new, powerful testimony of this Finnish composer's emotional sensitivity and originality. A true poet speaks to us ... in a clear and personal language..." As such, the review continued, Madetoja had no need to "dabble in hyper-modern forms of expression" that composers utilize when they need to compensate for "an inner emptiness".[5]

Premiere and other early performances

[edit]Despite having been published in 1921, The Garden of Death waited two years for its premiere. This occurred on 19 March 1923, when the Finnish pianist Elli Rängman-Björlin played Madetoja's suite during a public recital at University Hall in Helsinki.[6] It was the "domestic novelty"[2] on a program that also included: Ferruccio Busoni's transcription (1893) of the Chaconne from Bach's Partita for Violin No. 2, Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 32 (1822), César Franck's Prélude, Choral et Fugue (1884), two small piano pieces from Sibelius's (Opp. 58/4 and 58/8, 1909), the first (D-flat major) of Liszt's Two Concert Études (1863), and Carl Tausig's transcription (1869) of the first of Schubert's Three Marches Militaires.[2] At the conclusion of the performance, Madetoja—who was in attendance—received a "well-deserved" applause from the audience,[2] which—though large—failed to fill the ballroom due a scheduling conflict with the Finnish premiere of Sibelius's ballet-pantomime Scaramouche.[7]

The critics reviewed Madetoja's suite positively. Writing in Hufvudstadsbladet, Karl Ekman found the piece "as fine, atmospheric, and sonorous as anything this talented composer has created",[1] while in Uusi Suomi Heikki Klemetti described The Garden of Death as "tonally ... newish but tasteful, ... emotional poetry to the max".[6] In addition, the critics praised Rängman-Björlin, variously characterizing her playing of Madetoja's suite for its "delicate execution"[2] and "visionary finesse".[6] A few months later in May, Rängman-Björlin scored a success for Madetoja by performing The Garden of Death in Berlin and Dresden. It made a positive impression on the German critics. Emphasizing Rängman-Björlin's Finnish heritage, Allgemeine Musikzeitung wrote that Madetoja's "very attractive" suite had sprouted from "the national soil"; similarly, Dresdner Nachrichten described The Garden of Death as "finely colored and impressive music", the "strange, folk-like tone" of which had "charmed with its wonderfully barren sweetness".[8] Sächsische-Staatszeitung argued that with Madetoja's piece Rängman-Björlin had "achieved her greatest victory" of the evening.[8]

Near the turn of the decade, Madetoja's The Garden of Death also obtained the valuable advocacy of the Finnish pianist Kerttu Bernhard, who played the suite to acclaim in both Paris and Berlin in 1929.[9][10] In 1948, Madetoja's former student, Olavi Pesonen arranged The Garden of Death for orchestra. This arrangement, the manuscript of which Edition Wilhelm Hansen published in 2012, is scored for: 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (1 doubling cor anglais), 2 clarinets (in A), 2 bassoons, 4 horns (in F), 3 trumpets (in F), timpani, harp, and strings. As of 2022, no commercial recording of the orchestrated version of The Garden of Death has been made.

Structure

[edit]The Garden of Death, which lasts about 14 minutes, is in three movements. They are as follows:

The first movement, in common time, begins in E major. The second movement, in triple time, is a "haunting waltz" that beings in A major. The third movement, in cut time, is a "meditative lullaby" that begins in G-flat major.

Reception

[edit]The Finnish pianist Mika Rännäli, who recorded The Garden of Death in 2004, describes the piece as "one of the best and most poignant works [of the] Finnish piano literature": because "all encounter death", the suite's exploration of "the innermost recesses of the mind and the depths of the soul has a universal impact".[11]

Recordings

[edit]The sortable table below lists commercially available recordings of the Pastoral Suite:

| No. | Pianist | Rec.[d] | Time | Recording venue | Label | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Izumi Tateno | ? | 13:00 | ? | Toshiba Records | |

| 2 | Liisa Pohjola | 1982 | 14:30 | Sibelius Academy | Fennica Nova | |

| 3 | Mika Rännäli | 2004 | 14:11 | Tulindberg Hall, Oulu Music Centre | Alba Records | |

| 4 | Jouni Somero | 2007 | 15:40 | Kuusaa Hall, Kuusankoskitalo | FC Records |

Notes, references, and sources

[edit]- Notes

- ^ At its premiere, the Swedish-language press in Finland referred to Madetoja's suite as "Dödens trädgård".[1][2] Furthermore, the suite's Denmark-based publisher, Edition Wilhelm Hansen, provided the Danish "Dødens park'.

- ^ Tragedy struck Madetoja a second time about a month later on 18 May 1918: during May Day celebrations, his good friend and fellow composer Toivo Kuula got into an altercation with a group of White Army officers, one of whom shot him to death.[3]

- ^ In the late 1930s, the Finnish press began using the Finnish name for the third movement.

- ^ Refers to the year in which the performers recorded the work; this may not be the same as the year in which the recording was first released to the general public.

- ^ I. Tateno–Toshiba (TA–60001/60004) 1974

- ^ L. Pohjola–Fennica Nova (LP FENO 6) 1987

- ^ M. Rannali–Alba (ABCD 206) 2005

- ^ J. Somero–FC-Records (FCRCD–9718) 2008

- References

- ^ a b Hufvudstadsbladet, No. 77 1923, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Svenska Pressen, No. 66 1923, p. 4.

- ^ Pulliainen 2000, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Rännäli (2005), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Uusi Suomi, No. 222 1922, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Uusi Suomi, No. 65 1923, p. 9.

- ^ Iltalehti, No. 6 1923, p. 3.

- ^ a b Uusi Suomi, No. 119 1923, p. 8.

- ^ Uusi Suomi, No. 31 1929, p. 9.

- ^ Helsingin Sanomat, No. 75 1929, p. 15.

- ^ Rännäli 2005, p. 6.

- Sources

- Liner notes

- Pulliainen, Riitta (2000). Madetoja Orchestral Works 1: "I Have Fought My Battle" (booklet). Translated by Nimmo, James. Arvo Volmer & Oulu Symphony Orchestra. Alba. p. 4–6. ABCD 132. OCLC 45647644

- Rännäli, Mika (2005). Intimate garden: Leevi Madetoja complete piano works (CD booklet). Translated by Sinisalo, Susan. Mika Rännäli. Alba. p. 4–8. ABCD 206. OCLC 63178249

- Somero, Jouni (2008). An anthology of Finnish piano music, Vol. 4 (CD booklet). Translated by Sinisalo, Susan. Jouni Somero. FC Records. p. 5–6. FCRCD–9718. OCLC 905239541

- Newspaper articles (by date)

- "Suomalainen musiikki ulkomailla: Saksalainen arvostelu Leevi Madetojan "Kuoleman puutarhasta"" [Finnish music abroad: German review of Leevi Madetoja's Death Garden]. Uusi Suomi (in Finnish). No. 222. 27 September 1922. p. 8.

- A. L—n. [Laitinen, Arvo] [in Finnish] (20 March 1923). "Taide ja Kirjallisuus: Elli Rängman-Björlin'in" [Art and Literature: by Elli Rängman-Björlin]. Iltalehti (in Finnish). No. 66. p. 3.

- B. B—t. (20 March 1923). "Elli Rängman-Björlins konsert" [Elli Rängman-Björlin's concert]. Svenska Pressen (in Swedish). No. 66. p. 4.

- H. K. [Klemetti, Heikki] [in Finnish] (20 March 1923). "Elli Rängman-Björlinin konsertti" [Concert by Elli Rängman-Björlin]. Uusi Suomi (in Finnish). No. 65. p. 9.

- E. K—n. [Ekman, Karl] [in Finnish] (20 March 1923). "Elli Rängman-Björlins konsert" [Elli Rängman-Björlin's concert]. Hufvudstadsbladet (in Swedish). No. 77. p. 9.

- "Elli Rängman-Björlin Saksassa: Otteita saksalaisten lehtien arvosteluista" [Elli Rängman-Björlin in Germany: Excerpts from the reviews of German magazines]. Uusi Suomi (in Finnish). No. 119. 29 May 1923. p. 8.

- "Jälleen kotona: Kerttu Bernhard" [Home again: Kerttu Bernhard]. Uusi Suomi (in Finnish). No. 31. 1 February 1929. p. 9.

- "Kerttu Bernhardin ulkomaiset konsertit: Berliniläisiä ja parisilaisia arvosteluja" [Kerttu Bernhard's foreign concerts: Reviews from Berlin and Paris]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). No. 75. 17 March 1929. p. 15.